The Impact of Mobile Applications on Improving Oral Hygiene Knowledge and Skills of Adolescents: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

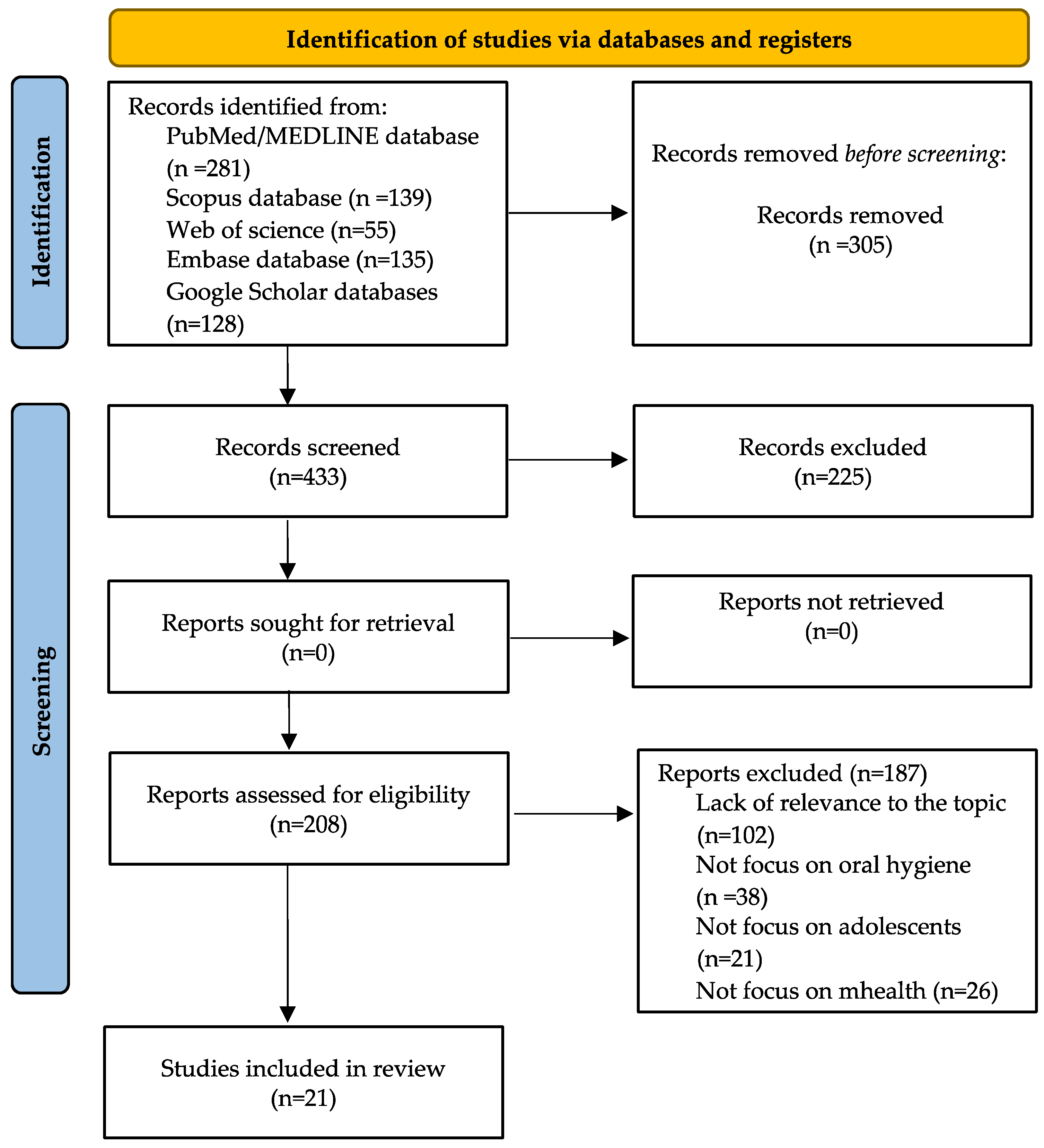

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Questions

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategies

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Selected Articles

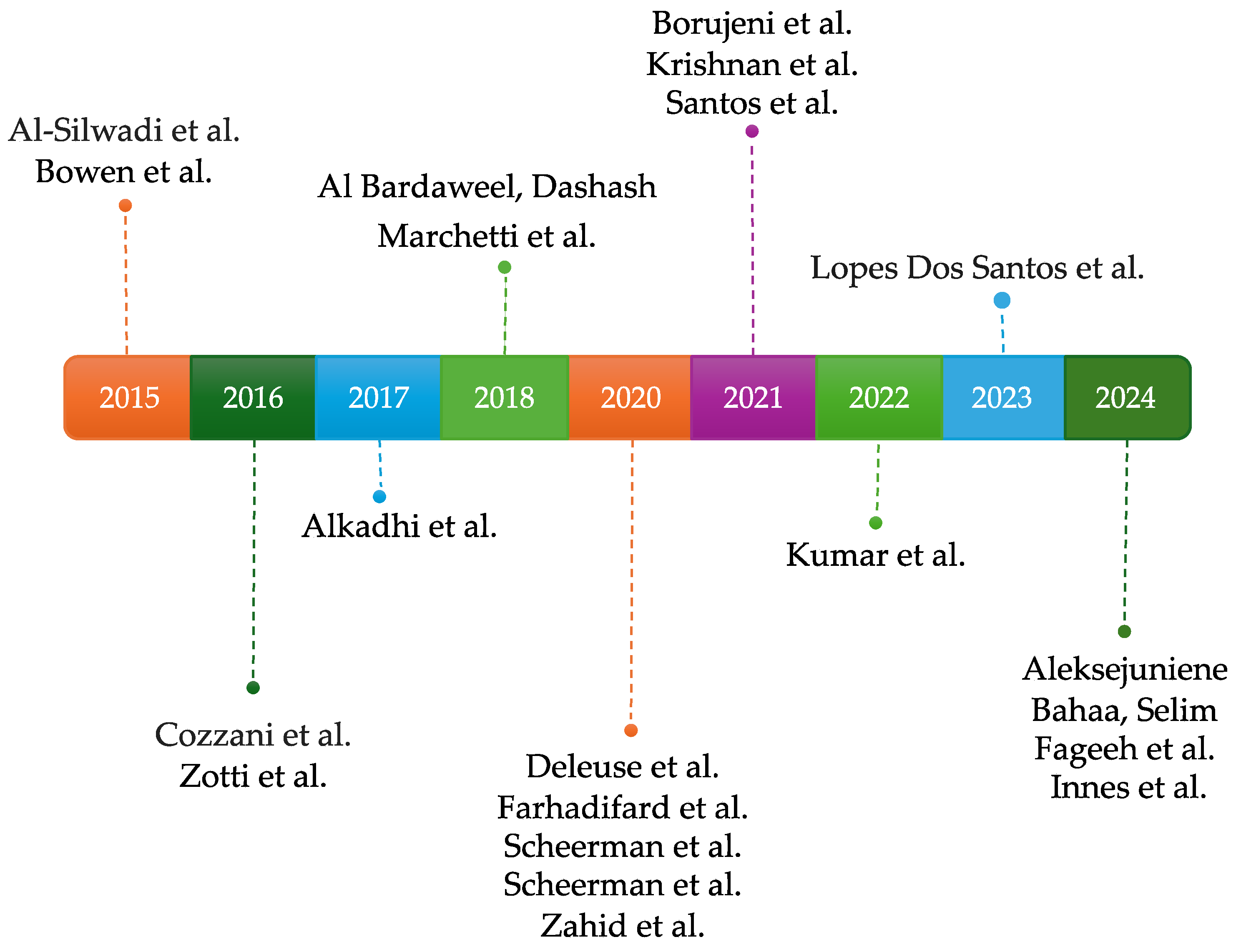

3.2. Distribution of Articles by Year of Publication

3.3. Distribution of Studies by Type of Technology Used

3.4. Risk of Bias in Included Studies

4. Discussion

Gaps in Literature and Future Research Challenges

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484 (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Wu, L.; Lo, E.C.M.; McGrath, C.; Wong, M.C.M.; Ho, S.M.Y.; Gao, X. Motivational interviewing for caries prevention in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.; Bougatsos, C.; Griffin, J.; Selph, S.S.; Ahmed, A.; Fu, R.; Nix, C.; Schwarz, E. Screening, referral, behavioral counseling, and preventive interventions for oral health in children and adolescents aged 5 to 17 years: A systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2023, 330, 1674–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall-Scullin, E.; Goldthorpe, J.; Milsom, K.; Tickle, M. A qualitative study of the views of adolescents on their caries risk and prevention behaviours. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antala, A.V.; Kariya, P.B. Social media as a tool for oral health education in early childhood and adolescents: Opportunities and challenges. Arch. Med. Health Sci. 2025, 10, 4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbricoli, L.; Bernardi, L.; Ezeddine, F.; Bacci, C.; Di Fiore, A. Oral hygiene in adolescence: A questionnaire-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhaija, E.S.A.; Al-Saif, E.M.; Taani, D.Q. Periodontal health knowledge and awareness among subjects with fixed orthodontic appliance. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2018, 23, e1–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Badawy, S.M.; Kuhns, L.M. Texting and mobile phone app interventions for improving adherence to preventive behavior in adolescents: A systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, S.R.; Albuquerque, T.S.; Luis, H.S.; Assunção, V.A.; Malmqvist, S.; Cuculescu, M.; Slusanschi, O.; Johannsen, G.; Galuscan, A.; Podariu, A.C.; et al. Oral health knowledge, perceptions, and habits of adolescents from Portugal, Romania, and Sweden: A comparative study. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2019, 9, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmal Muhamat, N.; Hasan, R.; Saddki, N.; Mohd Arshad, M.R.; Ahmad, M. Development and usability testing of mobile application on diet and oral health. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, A.M.; Aradhya, S. Impact of oral health education on oral hygiene knowledge, practices, plaque control and gingival health of 13- to 15-year-old school children in Bangalore city. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2013, 11, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, K.; Bharmal, R.V.; Sharif, M.O. The availability and characteristics of patient-focused oral hygiene apps. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunny, G. How Many People Own Smartphones in the World? (2024–2029). Available online: https://prioridata.com/data/smartphone-stats/ (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- WHO. Mobile Technologies for Oral Health: An Implementation Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-003522-5. Available online: https://www.dentalhealth.ie/assets/files/pdf/who-oh-mobile-tech-guide-.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Patil, S.; Hedad, I.A.; Jafer, A.A.; Abutaleb, G.K.; Arishi, T.M.; Arishi, S.A.; Arishi, H.A.; Jafer, M.; Gujar, A.N.; Khan, S.; et al. Effectiveness of mobile phone applications in improving oral hygiene care and outcomes in orthodontic patients. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2021, 11, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangle, S.; Yeravdekar, R.; Singh, A.; Mukherjee, S.K.; Jha, A.K. Mobile health applications: Variables influencing user’s perception and adoption intentions. In Accelerating Strategic Changes for Digital Transformation in the Healthcare Industry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, R.; Silveira, A.; Sequeira, T.; Durão, N.; Lourenço, J.; Cascais, I.; Cabral, R.M.; Taveira Gomes, T. Gamification and oral health in children and adolescents: A scoping review. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2024, 13, e35132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, B. What Are mHealth Apps? Types, Examples, Costs, and More. Available online: https://scopicsoftware.com/blog/mobile-health-apps/ (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Benson, P.E.; Parkin, N.; Dyer, F.; Millett, D.T.; Germain, P. Fluorides for preventing early tooth decay (demineralised lesions) during fixed brace treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 11, CD003809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C.E.; Maturana, C.A.; Coloma, S.I.; Carrasco-Labra, A.; Giacaman, R.A. Teledentistry and mHealth for promotion and prevention of oral health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Suprabha, B.S.; Rao, A. Teledentistry and its applications in paediatric dentistry: A literature review. Pediatr. Dent. J. 2021, 31, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estai, M.; Bunt, S.; Kanagasingam, Y.; Kruger, E.; Tennant, M. Diagnostic accuracy of teledentistry in the detection of dental caries: A systematic review. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2016, 16, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShaya, M.; Farsi, D.; Farsi, N. The accuracy of teledentistry in caries detection in children: A diagnostic study. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221109075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, M.; Deng, K.; Tullini, A.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Lai, H.; Tonetti, M.S. Enhanced control of periodontitis by an AI-enabled multimodal-sensing toothbrush and targeted mHealth micromessages: A randomized trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 1632–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.T.; Asimakopoulou, K. Managing oral hygiene as a risk factor for periodontal disease: A systematic review of psychological approaches to behaviour change for improved plaque control in periodontal management. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, S36–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaurani, P.; Choubisa, D. Oral Cancer and mHealth in India: An overview. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2020, 9, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Estai, M.; Pungchanchaikul, P.; Quick, K.; Ranjitkar, S.; Fashingbauer, E.; Askar, A.; Wang, J.; Diefalla, F.; Shenouda, M.; et al. Mobile health assessment of traumatic dental injuries using smartphone-acquired photographs: A multicenter diagnostic accuracy study. Telemed. e-Health 2024, 30, 2592–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaid, N.R.; Hansa, I.; Bichu, Y. Smartphone applications used in orthodontics: A scoping review of scholarly literature. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2020, 9, S67–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargozar, S.; Jadidfard, M.P. Teledentistry accuracy for caries diagnosis: A systematic review of in-vivo studies using extra-oral photography methods. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.M.; Yeo, A.N.; Lee, S.Y. Expert usability evaluation of a mobile application for systematic caries management in children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 17, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniazzo, M.P.; Nodari, D.; Muniz, F.W.M.G.; Weidlich, P. Effect of mHealth in improving oral hygiene: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem El Hajj, H.; Fares, Y.; Abou-Abbas, L. Assessment of dental anxiety and dental phobia among adults in Lebanon. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yu, K.F.; Liu, P.; Lee, G.H.M.; Wong, M.C.M. Can mHealth promotion for parents help to improve their children’s oral health? A systematic review. J. Dent. 2022, 123, 104185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirmohammadi, M.; Razeghi, S.; Shamshiri, A.R.; Mohebbi, S.Z. Impact of smartphone application usage by mothers in improving oral health and its determinants in early childhood: A randomized controlled trial in a pediatric dental setting. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 23, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, H.S.; Rosli, T.I.; Rani, H.; Ashar, A. mHealth and oral health care among older people: A narrative review. J. Res. Med. Dent. Sci. 2024, 12, 9–18. Available online: https://www.jrmds.in/articles/-1099949.html (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Scribante, A.; Cosola, S.; Pascadopoli, M.; Genovesi, A.; Battisti, R.A.; Butera, A. Clinical and Technological Evaluation of the Remineralising Effect of Biomimetic Hydroxyapatite in a Population Aged 6 to 18 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butera, A.; Maiorani, C.; Gallo, S.; Pascadopoli, M.; Buono, S.; Scribante, A. Dental Erosion Evaluation with Intact-Tooth Smartphone Application: Preliminary Clinical Results from September 2019 to March 2022. Sensors 2022, 22, 5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, A.; Shenoy, R.P.; Mohammad, I.P.; Junaid, A.; Amanna, S. Chances and challenges of mobile health in public health dentistry. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2023, 17, ZE13–ZE16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väyrynen, E.; Hakola, S.; Keski-Salmi, A.; Jämsä, H.; Vainionpää, R.; Karki, S. The use of patient-oriented mobile phone apps in oral health: Scoping review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2023, 11, e46143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Mumin, N.; Yusof, Z.Y.M.; Marhazlinda, J.; Obaidellah, U. Adolescents’ opinions on the use of a smartphone application as an oral health education tool: A qualitative study. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221114190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajay, K.; Azevedo, L.B.; Haste, A.; Morris, A.J.; Giles, E.; Gopu, B.P.; Subramanian, M.P.; Zohoori, F.V. App-based oral health promotion interventions on modifiable risk factors associated with early childhood caries: A systematic review. Front. Oral Health 2023, 4, 1125070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, N.; Gholamzadeh, M.; Zahednamazi, S.; Ayyoubzadeh, S.M. Mobile health applications for children’s oral health improvement: A systematic review. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2023, 37, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijačko, N.; Gosak, L.; Cilar, L.; Novšak, A.; Creber, R.M.; Skok, P.; Štiglic, G. The Effects of Gamification and Oral Self-Care on Oral Hygiene in Children: Systematic Search in App Stores and Evaluation of Apps. JMIR MHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e16365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.O.; Newton, T.; Cunningham, S.J. A systematic review to assess interventions delivered by mobile phones in improving adherence to oral hygiene advice for children and adolescents. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Santo, K.; Wong, G.; Sohn, W.; Spallek, H.; Chow, C.; Irving, M. Mobile apps for dental caries prevention: Systematic search and quality evaluation. JMIR MHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e19958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Miami, FL, USA, 2024; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkadhi, O.H.; Zahid, M.N.; Almanea, R.S.; Althaqeb, H.K.; Alharbi, T.H.; Ajwa, N.M. The effect of using mobile applications for improving oral hygiene in patients with orthodontic fixed appliances: A randomized controlled trial. J. Orthod. 2017, 44, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Silwadi, F.M.; Gill, D.S.; Petrie, A.; Cunningham, S.J. Effect of social media in improving knowledge among patients having fixed appliance orthodontic treatment: A single-center randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 148, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bardaweel, S.; Dashash, M. E-learning or educational leaflet: Does it make a difference in oral health promotion? A clustered randomized trial. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahaa, S.; Selim, K. Effectiveness of smartphone application in improving oral hygiene compared to oral instructions in patients with plaque-induced gingivitis: A randomized controlled trial. Egypt. Dent. J. 2024, 70, 3259–3266. [Google Scholar]

- Borujeni, E.S.; Sarshar, F.; Nasiri, M.; Sarshar, S.; Jazi, L. Effect of teledentistry on the oral health status of patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment at the first three follow-up visits. Dent. Med. Probl. 2021, 58, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, T.B.; Rinchuse, D.J.; Zullo, T.; DeMaria, M.E. The influence of text messaging on oral hygiene effectiveness. Angle Orthod. 2015, 85, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzani, M.; Ragazzini, G.; Delucchi, A.; Mutinelli, S.; Barreca, C.; Rinchuse, D.J.; Servetto, R.; Piras, V. Oral hygiene compliance in orthodontic patients: A randomized controlled study on the effects of a post-treatment communication. Prog. Orthod. 2016, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuse, M.; Meiffren, C.; Bruwier, A.; Maes, N.; Le Gall, M.; Charavet, C. Smartphone application-assisted oral hygiene of orthodontic patients: A multicentre randomized controlled trial in adolescents. Eur. J. Orthod. 2020, 42, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fageeh, H.N.; Mansoor, M.A.; Fageeh, H.I.; Abdul, H.N.; Khan, H.; Akkam, A.; Muhaddili, I.; Korairi, S.; Bhati, A.K. “Teledentistry” using a mobile app (Telesmile) to improve oral health among the visually impaired and hearing-impaired populations in Saudi Arabia: A randomized controlled study. Front. Oral Health 2024, 5, 1496222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadifard, H.; Soheilifar, S.; Farhadian, M.; Kokabi, H.; Bakhshaei, A. Orthodontic patients’ oral hygiene compliance by utilizing a smartphone application (Brush DJ): A randomized clinical trial. BDJ Open 2020, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, N.; Fairhurst, C.; Whiteside, K.; Ainsworth, H.; Sykes, D.; El Yousfi, S.; Turner, E.; Chestnutt, I.G.; Keetharuth, A.; Dixon, S.; et al. Behaviour change intervention for toothbrushing (lesson and text messages) to prevent dental caries in secondary school pupils: The BRIGHT randomized control trial. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2024, 52, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.S.K.; Deshpande, A.P.; Ankola, A.V.; Sankeshwari, R.M.; Jalihal, S.; Hampiholi, V.; Khot, A.J.P.; Hebbal, M.; Kotha, S.L. Effectiveness of a visual interactive game on oral hygiene knowledge, practices, and clinical parameters among adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Children 2022, 9, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes Dos Santos, R.; Spinola, M.D.S.; Carvalho, E.; Lopes Dos Santos, D.C.; Dame-Teixeira, N.; Heller, D. Effectiveness of a new app in improving oral hygiene in orthodontic patients: A pilot study. Int. Dent. J. 2023, 73, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, G.; Fraiz, F.C.; Nascimento, W.M.D.; Soares, G.M.S.; Assunção, L.R.D.S. Improving adolescents’ periodontal health: Evaluation of a mobile oral health App associated with conventional educational methods: A cluster randomized trial. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2018, 28, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.B.; Pereira, L.C.; Neves, J.G.; Pithon, M.M.; Santamaria, M. Can text messages encourage flossing among orthodontic patients? Angle Orthod. 2021, 91, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerman, J.F.M.; van Meijel, B.; van Empelen, P.; Verrips, G.H.W.; van Loveren, C.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Pakpour, A.H.; van den Braak, M.C.T.; Kramer, G.J.C. The effect of using a mobile application (“WhiteTeeth”) on improving oral hygiene: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 18, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerman, J.F.M.; Hamilton, K.; Sharif, M.O.; Lindmark, U.; Pakpour, A.H. A theory-based intervention delivered by an online social media platform to promote oral health among Iranian adolescents: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Health 2020, 35, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotti, F.; Dalessandri, D.; Salgarello, S.; Piancino, M.; Bonetti, S.; Visconti, L.; Paganelli, C. Usefulness of an app in improving oral hygiene compliance in adolescent orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod. 2016, 86, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksejuniene, A.M.J. Theory-guided reminder strategy for promoting oral health in adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2024, 10, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, L.; Iyer, K.; Kumar, P.D.M. Effectiveness of two sensory-based health education methods on oral hygiene of adolescent with autism spectrum disorders: An interventional study. Spec. Care Dentist. 2021, 41, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahid, T.; Alyafi, R.; Bantan, N.; Alzahrani, R.; Elfirt, E. Comparison of effectiveness of mobile app versus conventional educational lectures on oral hygiene knowledge and behavior of high school students in Saudi Arabia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 1901–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed-Ariss, R.; Baildam, E.; Campbell, M.; Chieng, A.; Fallon, D.; Hall, A.; McDonagh, J.E.; Stones, S.R.; Thomson, W.; Swallow, V. Apps and adolescents: A systematic review of adolescents’ use of mobile phone and tablet apps that support personal management of their chronic or long-term physical conditions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, S.J.; Parikh, N.; Majmudar, S.; Pin, S.; Wang, C.; Willis, L.; Haga, S.B. A systematic review of the scope of study of mHealth interventions for wellness and related challenges in pediatric and young adult populations. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2022, 13, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.-M.; Park, B.-Y.; Noh, H.-J. Efficacy of mobile health care in patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment: A systematic review. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2021, 19, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, R.C.W.; Thu, K.M.; Chaurasia, A.; Hsung, R.T.C.; Lam, W.Y.-H. A Systematic Review of the Use of mHealth in Oral Health Education among Older Adults. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.R.H.; Ng, E.; Chow, D.Y.; Sim, C.P.C. The use of artificial intelligence to aid in oral hygiene education: A scoping review. J. Dent. 2023, 135, 104564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascadopoli, M.; Zampetti, P.; Nardi, M.G.; Pellegrini, M.; Scribante, A. Smartphone applications in dentistry: A scoping review. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, G.D.; Speckemeier, C.; Abels, C.; Plescher, F.; Börchers, K.; Wasem, J.; Blase, N.; Neusser, S. Problems and barriers related to the use of digital health applications: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database Name | Search Terms | Number of Articles Found |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed/Medline | teledentistry OR mHealth OR mobile application OR mobile apps OR mHealth AND adolescents OR oral hygiene AND adolescents AND mHealth, oral hygiene AND adolescents AND mobile application OR teledentistry AND mHealth | 281 |

| Scopus | teledentistry AND mHealth AND adolescents OR mHealth AND adolescents AND oral health OR mobile application AND adolescents AND oral health OR smartphone apps AND oral health AND adolescents | 139 |

| Web of Science | teledentistry AND adolescents OR mobile application AND oral health OR mHealth AND young adults AND oral health OR mobile application AND adolescents AND oral hygiene | 55 |

| Embase | adolescents AND mHealth AND oral AND health OR adolescents AND mobile application AND oral AND health OR oral AND hygiene AND teledentistry OR orthodontic AND patients AND mHealth OR preventive AND oral AND health AND adolescents AND mHealth | 135 |

| Google Scholar | teledentistry, adolescents, oral health OR mHealth, adolescents, oral hygiene OR mobile applications, adolescents, oral hygiene OR adolescents, oral prevention, mHealth OR adolescents, oral health promotion, mHealth | 128 |

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Type of study | Randomized and non-randomized clinical trials | Systematic review, narrative review, scoping review, qualitative studies (focus groups) |

| Participants | Adolescents (aged 10–19 years) | Other age groups (under 10 years or over 19 years) |

| Evaluation period | Articles published between 2015 and 2024 | Articles published before 2015 |

| Availability | Full-text articles in English, with open access or institutional access | Abstract-only articles, non-open access articles, duplicates, articles published in other languages |

| Intervention | Use of mobile health (mHealth) technology to raise awareness of oral hygiene for preventing dental caries and gingival diseases | Irrelevant articles that do not align with the study’s objectives |

| Author, Year, Country | Purpose | Study Design (RCT/Non-RCT) | Sample Size | Test Group | Control Group | Follow-Up Time | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleksejuniene, 2024, Canada [68] | To evaluate the impact of an SMS reminder strategy on adolescents’ oral self-care skills, diet knowledge, and behavior. | Non-RCT | n = 43 | The adolescents (ages 11–14) received SMS reminders for oral health education following the health belief model. Oral health knowledge and oral self-care skills were assessed at the baseline (prior to education), 5 weeks (first follow-up), and 6 months (second follow-up) after the education. | No control group | 6 months | Toothbrushing skill scores improved significantly (p < 0.001), rising from a mean of 7.0 (SD 1.9) at baseline to 14.4 (SD 2.6) at the first follow-up and 14.2 (SD 2.7) at the second follow-up. The toothbrushing time also significantly (p < 0.001) increased from the mean time of 51.5 (24.4) at the baseline to 112.7 (30.1) seconds at the first and to 107.2 (22.2) at the second follow-up. Diet knowledge scores improved from an average of 14.6 (4.1) at baseline to 28.0 (2.7) at the first follow-up and 25.0 (3.1) at the second follow-up. The mean sugar intake scores decreased from 12.6 (2.2) at baseline to 11.9 (1.9) at the first follow-up and 11.5 (1.9) at the second follow-up. |

| Alkadhi et al., 2017, Saudi Arabia [50] | To compare the impact of mobile app reminders versus verbal instructions on improving oral hygiene. | RCT | Test group n = 22 Control group n = 22 | Participants received a mobile app with thrice-daily oral hygiene reminders | Participants received verbal oral hygiene instructions during routine orthodontic visits | 4 weeks | Non-significant differences were found at baseline between the two groups in PI and GI values (PI = 0.8050 ± 0.4062 and GI = 0.3450 ± 0.2955 in the study group, and PI = 0.8959 ± 0.4824 and GI = 0.4927 ± 0.3005 in the control group). Significant differences were found in PI and GI (p = 0.04 and p = 0.02, respectively) between groups after 4 weeks (PI = 0.6677 ± 0.3146 and GI = 0.2273 ± 0.2256 in the study group, and PI = 0.9891 ± 0.5244 and GI = 0.5941 ± 0.5679 in the control group). |

| Al-Silwadi et al., 2015, UK [51] | To evaluate whether providing audiovisual information on YouTube improves orthodontic patients’ knowledge compared to traditional methods. The study also examined the effects of gender and ethnicity. | RCT | Test group n = 30 Control group n = 30 | Participants (aged 13 and over) received standard verbal and written information about fixed appliances. They also received three emails over 6 weeks asking them to watch a 6-min YouTube video with similar audiovisual content. Patient knowledge was assessed using questionnaires at baseline and 6 to 8 weeks later. | Participants (aged 13+ years) received standard verbal and written information about fixed appliances. | 8 weeks | The intervention group showed significantly better knowledge improvement than the control group, scoring nearly 1 point higher on average (95% CI: 0.305–1.602; p = 0.005). Ethnicity had a notable impact on knowledge improvement: non-Caucasian patients achieved higher scores on the second questionnaire compared to Caucasian patients, with an average difference of 0.798 points (0.158–1.438; p = 0.016). Gender, however, did not show a significant effect. Adding audiovisual information via the Internet to verbal and written patient information should be considered. |

| Al Bardaweel, Dashash, 2018, Siria [52] | To compare the effectiveness of traditional educational leaflets versus E-applications in enhancing oral health knowledge, oral hygiene, and gingival health among schoolchildren. | RCT | Test group n = 104 Control group n = 107 | Schoolchildren aged 10–11 used an e-learning program for oral health education. Questionnaires were used for oral health knowledge assessment. Dental plaque was measured with PI and gingival health with GI. | Schoolchildren aged 10–11 received leaflets for oral health education. | 12 weeks | At both the 6-week (p < 0.05) and 12-week (p < 0.05) intervals, the leaflet cluster demonstrated statistically significantly higher oral health knowledge compared to the e-learning cluster: the average knowledge score was 82.87 ± 10.69 at 6 weeks and 89.12 ± 8.16 at 12 weeks in the leaflet group, while the e-learning group showed values of 72.16 ± 10.25 at 6 weeks and 74.66 ± 8.98 at 12 weeks. Children in the leaflet group had significantly less plaque than those in the e-learning group at 6 weeks (PI = 1.06 ± 0.33 and 1.31 ± 0.39, respectively; p < 0.05) and at 12 weeks (PI = 0.85 ± 0.35 and 1.21 ± 0.40, respectively; p < 0.05). Children in the leaflet group had significantly better gingival health than the e-learning group at 6 weeks (GI = 0.88 ± 0.2 and 1.17 ± 0.25, respectively; p < 0.05) and 12 weeks (GI = 0.74 ± 0.22 and 1 ± 0.25, respectively; p < 0.05). |

| Bahaa, Selim, 2024, Egypt [53] | To examine the extent to which using a smartphone application as an educational tool and reminder of oral hygiene instructions affects patients’ oral health. | RCT | Test group n = 30 Control group n = 30 |

“Healthy Teeth–Tooth Brushing Reminder with timer”, an application that acts as a reminder twice a day for tooth brushing, was used in the test group (12–19 years old). GI and Quigley–Hein Turesky modified index (QHTMI) were assessed at baseline (T0) and after two months of instructions (T1). | The control group (12–19 years old) was informed of the oral hygiene instructions verbally at the baseline. | 2 months | A statistically significant difference was found in the mean GI score and the mean QHTMI score of the test and control groups (p = 0.0002; 0.0053) respectively. While there was no statistically significant difference in the mean GI score of the oral instructions group at T0 (2.33 ± 0.66) and T1 (2.07 ± 0.69), the mean GI score of the smartphone group at T0 (2.23 ± 0.73) and T1(1.17 ± 0.74) showed a statistically significant difference. The mean score of QHTMI in the smartphone group (1.97 ± 1.03) had the most significant improvement compared to baseline (3.27 ± 1.26). |

| Borujeni et al., 2021, Iran [54] | To assess the impact of teledentistry on the oral health of patients with fixed orthodontic treatment during the initial and three follow-up visits. | RCT | Test group n = 30 Control group n = 30 | Participants (12+ years old) who were about to begin fixed orthodontic treatment were sent an educational video via the Telegram application at baseline. PI, BOP, gingival color, and consistency were analyzed in the next three follow-up appointments. | Participants (12+ years old) who were about to begin fixed orthodontic treatment received at baseline in-person education on maintaining oral hygiene during treatment. | 12 weeks | A statistically significant difference in PI and BOP was observed between the two groups at the third and fourth appointments. PI values were 32.82 ± 18.21 in the teledentistry group and 46.45 ± 22.11 in the control group. BOP values were 23.40 ± 15.73 in the teledentistry group and 36.00 ± 23.24 in the control group. However, the gingival color and consistency did not show a significant variation in relation to the method of education (p > 0.05). Additionally, patient age did not significantly influence oral health status in either group (p > 0.05). |

| Bowen et al., 2015, United States [55] | To study the impact of text message reminders on oral hygiene and plaque removal in adolescent orthodontic patients. | RCT | Test group n = 30 Control group n = 30 | Twenty-five orthodontic adolescent patients were included in the text message group and watched, at baseline, an audiovisual presentation on how to properly brush, then received 12 messages over a period of 4 weeks, followed by 1 message per week for 8 additional weeks. Plaque was measured using planimetry. Photographs were taken at the start (T0), 4 weeks later (T1), and 12 weeks after the start (T2). | Twenty-five orthodontic adolescent patients who watched, at baseline, an audiovisual presentation on how to properly brush with a conventional toothbrush using the Bass technique | 12 weeks | At T1 and T2, a significant reduction in dental plaque was observed in the test group compared to the control group. At T1, the values were 0.236 ± 0.026 for the test group and 0.438 ± 0.025 for the control group. At T2, the values were 0.221 ± 0.031 for the test group and 0.579 ± 0.030 for the control group. The conclusion was that text messages promoting good oral hygiene led to a reduction in the measurable surface area of plaque over time. |

| Cozzani et al., 2016, Italy [56] | To assess the impact of structured follow-up communication after the application of orthodontic appliances on oral hygiene adherence in 30–40 days. | RCT | Test group 1 n = 28 Test group 2 n = 26 Control group n = 30 | Among orthodontic patients (age 10–19 years), the first test group received a reassuring structured text message, and the second test group received a structured phone call to encourage appropriate dental hygiene 5–7 h after bonding. The Plaque Index was measured for all patients. | Orthodontic patients (age 10–19 years) who received no post-procedure communication | 30–40 days | Participants who received post-treatment communication showed higher oral hygiene compliance than those in the control group, with plaque indices of 0.3 and 0.75, respectively (p = 0.0205). Follow-up after orthodontic treatment may effectively enhance short-term oral hygiene compliance. |

| Deleuse et al., 2020, Belgium [57] | To compare the effectiveness of a standard oscillating/rotating electric toothbrush to an interactive version connected to a brushing aid app in adolescents with fixed orthodontic appliances. | RCT | Test group n = 19 Control group n = 19 | Adolescents (12–18 years) with full-fixed orthodontic appliances used an interactive oscillating/rotating electric toothbrush connected to a brushing aid app. At baseline, all patients received verbal and written oral hygiene instructions. Patients were evaluated for PI, GI, and WSL from baseline (T1) to the end of the study (T4). | Adolescents (12–18 years) with full-fixed orthodontic appliances used an oscillating/rotating electric toothbrush alone. At baseline, all patients received verbal and written oral hygiene instructions. | 18 weeks | From T1 to T4, the PI significantly decreased in both groups (control: p < 0.0001; test: p = 0.0003), with no significant difference between them. Similarly, the GI significantly decreased in both groups (control: p = 0.0028; test: p = 0.0008) and showed no difference between them. WSL scores remained stable in both groups (control: p = 0.066; test: p = 0.73) with no significant difference (p = 0.28). |

| Fageeh et al., 2024, Saudi Arabia [58] | To evaluate the effectiveness of the Telesmile mobile app in improving oral health knowledge and hygiene practices among individuals who were blind and deaf. | RCT | Test group n = 50 Control group n = 50 | Participants aged 12–18 (blind n = 25, deaf n = 25) used the Telesmile app, featuring multimedia Arabic dental sign language videos for patients with deafness and audio-recorded oral hygiene instructions for patients with blindness. Participants’ knowledge was assessed using a close-ended questionnaire at the initial visit (T0) and after 4 weeks (T1). | Subjects aged 12–18 (blind n = 25, deaf n = 25) received regular oral hygiene instructions. | 4 weeks | Initially, participants who were blind and deaf had poor knowledge of oral health and hygiene (T0). After using the Telesmile app for 4 weeks (T1), their knowledge significantly improved (p< 0.001). Audio techniques effectively educated blind participants, while video demonstrations enhanced the oral health knowledge of deaf individuals. |

| Farhadifard et al., 2020, Iran [59] | To evaluate the effectiveness of the Brush DJ smartphone application in promoting oral hygiene adherence among patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. | RCT | Test group n = 60 Control group n = 60 | Patients aged 15–25 starting fixed orthodontic treatment received conventional oral hygiene instruction, then used the Brush DJ app. PI and GI were measured at baseline (T0), and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks (T3). Tooth brushing frequency and duration were also recorded. | Patients aged 15–25 starting fixed orthodontic treatment received conventional oral hygiene instruction. | 12 weeks | PI and GI improved in the intervention group but worsened in the control group, showing significant differences (p < 0.001). PI decreased from T0 = 75.21 ± 13.36 to T3 = 67.84 ± 12.33 in the interventional group and increased from T0 = 76.59 ± 12.76 to T3 = 80.82 ± 10.5 in the control group. GI drcreased from T0 = 1.29 ± 0.49 to T3 = 0.95 ± 0.43 in the intervention group and from T0 = 1.49 ± 0.59 to T3 = 1.43 ± 0.56 in the control group. Increased brushing frequency and duration were linked to app usage during follow-up. |

| Innes et al., 2024, UK [60] | To evaluate the effectiveness of promoting toothbrushing to prevent dental caries (Brushing RemInder 4 Good oral HealTh, BRIGHT) in UK secondary schools. | RCT | Test group n = 2262 Control group n = 2418 | Pupils aged 11–13 who owned mobile phones and attended secondary schools with high free meal eligibility received a lesson and twice-daily texts. | Pupils aged 11–13 who received routine education | 2.5 years | At 2.5 years, no significant difference in caries prevalence was observed. Twice-daily toothbrushing rates initially reported by 77.6% of pupils increased at 6 months (intervention: 86.9%; control: 83.0%; OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.03–1.63, p = 0 .03) but showed no difference at 2.5 years (intervention: 81.0%; control: 79.9%; OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.84–1.30, p = 0.69). |

| Krishnan et al., 2021, India [69] | To assess the impact of two sensory-based interventions—visual pedagogy and the mobile app Brush Up—on improving oral health in adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. | Non-RCT | Visual pedagogy group n = 30 Brush Up - mobile application group n = 30 | Children with ASD aged 13–17 years used the Brush Up mobile application, based on oral health education, with an interactive toothbrush training game in it. Plaque Index and Gingival Index were assessed at baseline, after the 6th week, and after the 12th week. | Children with ASD aged 13–17 years received visual pedagogy—visual cards depicting toothbrushing technique, to be taken at home. | 12 weeks | Significant differences in plaque (p < 0.001) and gingival scores (p < 0.001) were observed among groups at 6 and 12 weeks after intervention. No significant differences in dental plaque (p = 0.912; 1.023; 0.812) or gingival scores (p = 0.932; 0.264; 0.283) were noted between the groups at any timepoint: PI = 2.02, 1.00, and 0.45; GI = 1.05, 0.61, and 0.28 in visual pedagogy group; PI = 2.02, 1.00, and 0.46; GI = 1.03, 0.58, and 0.24 in Brush Up group. |

| Kumar et al., 2022, India [61] | To compare the effects of an interactive game-based visual performance technique (IGVP) and traditional oral health education (OHE) on plaque control, gingival health, and knowledge and practices of oral hygiene. | RCT | Test group n = 50 Control group n = 50 | Children aged 12–15 received the IGVP technique. | Children aged 12–15 received traditional OHE | 3 months | The test group had a 58.7% reduction in gingival scores and a 63.4% reduction in plaque scores after intervention compared to the control group, which showed 2.8% and 0.7% reductions (p < 0.001). The test group also gained 22.4% more knowledge, while the control group gained 7.8%. |

| Lopes Dos Santos et al., 2023, Brazil [62] | To assess the impact of a mobile app on the oral hygiene (OH) of adolescents with fixed orthodontic appliances. | RCT | Test group n = 4 Control group n = 4 | Adolescents (14–19 years old) received OH guidance and motivation via a custom app. Clinical assessments using VPI and GBI were conducted at five time points: before orthodontic device application (T0); at baseline (T1); and 30 (T2), 60 (T3), and 90 (T4) days after. | Adolescents (14–19 years old) received standard OH instructions. | 90 days | Although no significant difference could be observed, VPI at T1 and T2 were lower for volunteers in the experimental group (33.20 ± 19.29; 32.10 ± 7.72) than for the volunteers in the control group (42.11 ± 8.56; 43.59 ± 34.71). The same was observed for GBI, in which volunteers in the experimental group presented lower GBI at T1 and T2 (12.70 ± 8.10; 13.72 ± 7.39) than volunteers in the control group (27.53 ± 17.89; 20.38 ± 9.95). Good acceptance for using the app was shown by volunteers. |

| Marchetti et al., 2018, Brazil [63] | To assess the effectiveness of a mobile oral health app associated with conventional educational methods in improving adolescents’ periodontal health | RCT | Test group n = 141 Control group n = 147 | Adolescents aged 14–19 years received oral guidance (OG) on oral health maintenance. Two sub-groups were created: one sub-group received access to a mobile oral health app where reinforcement messages were sent twice a day for a period of 30 days, and the other did not use the app. The knowledge score (KS) on oral health, OHI-S, and GBI were assessed at baseline and 20 weeks after. | Adolescents aged 14–19 years received video guidance (VG) on oral health maintenance. Two sub-groups were created: one sub-group received access to a mobile oral health app where reinforcement messages were sent twice a day for a period of 30 days, and the other did not use the app. | 20 weeks | A significant difference was observed in the KS mean in the follow-up test among the adolescents who used the app (mean = 4.77 ± 0.52) and those who did not have access to this educational method (4.35 ± 0.66; p < 0.001), regardless of the type of previous intervention (OG or VG). OHI-S and GBI decreased significantly (p < 0.001) in all groups, with no significant differences between groups. The app was effective in increasing knowledge, especially associated with video. The different methods were equally effective for a better standard of oral hygiene. |

| Santos et al., 2021, Brazil [64] | To evaluate how WhatsApp text messages affect patient awareness of daily oral hygiene and flossing importance. | RCT | Test group n = 22 Control group n = 22 |

Patients with a mean age of 14.3 ± 2.6 years with fixed orthodontic appliances received instructions on toothbrushing and flossing and daily WhatsApp text messages. PI, GBI, and halitosis were assessed at baseline and after 30 days. | Patients with a mean age of 14.3 ± 2.6 years with fixed orthodontic appliances received instructions on toothbrushing and flossing only, with no text messages. | 30 days |

Flossing frequency increased in both groups. In the test group, the frequency rose by 59.1% (p < 0.001), significantly higher than the control group (p > 0.05). The control group showed a 31.8% rise in frequency (p < 0.03). PI and GBI significantly decreased over time in both groups; PI decreased from 3.0 to 2.0 in the test group and from 2.5 to 2.0 in the control group, and GBI decreased from 3.0 to 2.0 in both groups (p < 0.05). In the test group, the halitosis score decreased significantly (p < 0.05) |

| Scheerman et al., 2020, Iran [65] | To assess the effectiveness of the WhiteTeeth mobile app, a theory-based mHealth program for oral hygiene improvement in adolescent orthodontic patients. | RCT | Test group n = 67 Control group n = 65 |

Adolescent orthodontic patients received the WhiteTeeth app alongside usual care. Data (Plaque Index, bleeding on probing index, and a questionnaire on oral health behavior) were collected at three check-ups: baseline (T0), 6 weeks (T1), and 12 weeks (T2). | Adolescent orthodontic patients received usual care only | 12 weeks | At 6 weeks, the intervention significantly reduced gingival bleeding (B = −3.74; 95% CI −6.84 to −0.65) and increased fluoride mouth rinse use (B = 1.93; 95% CI 0.36 to 3.50). At 12 weeks, the intervention group showed a greater reduction in dental plaque accumulation (B = −11.32; 95% CI −20.57 to −2.07) and in the number of plaque-covered sites (B = −6.77; 95% CI −11.67 to −1.87) compared to the control group. |

| Scheerman et al., 2020, Iran [66] | To test the effectiveness of a theory-based program using Telegram (an online social media platform) to promote oral hygiene among Iranian teenagers. | RCT | Group A n = 253 GroupA + M n = 260 Control group n = 278 | Group A: Telegram group with adolescents (12–17 years) only. Group A + M: Telegram group with adolescents and mothers. Periodontal condition and plaque status were assessed by two trained dental professionals using the VPI and CPI. | Adolescents (12–17 years) did not receive any intervention during the experimental phase of the intervention. | 6 months | At 1- and 6-month follow-ups, toothbrushing frequency was significantly higher in both intervention groups compared to the control. The A + M group showed greater improvements in toothbrushing, VPI (from 2.71 to 2.12), and CPI (from 1.68 to 1.33) scores than the A group. At 6 months, the A + M group also reported significantly more perceived social support from mothers than the A and control groups. |

| Zahid et al., 2020, Saudi Arabia [70] | To assess the impact of two oral health education approaches—the Brush DJ mobile app and conventional lectures—on high-school children’s oral hygiene knowledge and behavior. | Non-RCT | Test group n = 130 Control group n = 141 | The mobile app group used the app twice daily for 3 months. | The conventional education group received a 20 min lecture on oral hygiene using a whiteboard, markers, slides, and dental models. | 3 months | The Brush DJ app was as effective as educational lectures in improving oral health knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Both groups showed significant improvements in most areas, except for the app group’s toothbrushing frequency and duration. No change was seen in twice-daily brushing among app users, and less than 40% brushed for 2 min. In contrast, the lecture group showed significant improvement in these areas: the percentage of subjects reporting twice-daily brushing increased from 52.5% to 75.0%. The app was also found to be more difficult to use than the lectures (p = 0.037). |

| Zotti et al., 2016, Italy [67] | To test the effectiveness of an app-based protocol for oral hygiene maintenance in improving compliance and oral health in adolescents with fixed multibracket appliances. | RCT | Test group n = 40 Control group n = 40 | Adolescents starting orthodontic multibracket treatment received standardized oral hygiene instructions at baseline and were enrolled in a WhatsApp chat room-based competition and instructed to share monthly two self- photographs (selfies) with the other participants showing their oral hygiene status. PI, GI, WSL, and caries presence were recorded for all patients. | Adolescents starting orthodontic multibracket treatment received standardized oral hygiene instructions at baseline. | 12 months | After 6, 9, and 12 months, the study group had significantly lower PI and GI scores and a reduced incidence of new WSL compared to the control group. PI for the control group at T0 was 0.48(0.34) and at T4 was 1.79(0.54), and PI for the study group at T0 was 0.41 (0.32) and at T4 was 1.06(0.47). GI for the control group at T0 was 1.17(0.66) and at T4 was 1.40(0.57), and GI for the study group at T0 was 1.18(0.67) and at T4 was 0.67(0.36). The number of patients with WSL was 4(T0) and 7 (T4) in the study group and 5 (T0) and 16 (T4) in the control group. |

| Bias Arising from the Randomization Process | Bias Due to Deviations From Intended Interventions | Bias Due to Missing Outcome Data | Bias in Measurement of the Outcome | Bias in Selection of the Reported Result | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkadhi et al., 2017 [50] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Al-Silwadi et al., 2015 [51] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Al Bardaweel, Dashash, 2018 [52] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Bahaa, Selim, 2024 [53] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Borujeni et al., 2021 [54] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Bowen et al., 2015 [55] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Cozzani et al., 2016 [56] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Deleuse et al., 2020 [57] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Fageeh et al., 2024 [58] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Farhadifard et al., 2020 [59] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Innes et al., 2024 [60] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Kumar et al., 2022 [61] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Lopes Dos Santos et al., 2023 [62] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Marchetti et al., 2018 [63] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Santos et al., 2021 [64] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Scheerman et al., 2020 [65] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Scheerman et al., 2020 [66] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Zotti et al., 2016 [67] |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleksejuniene, 2024 [68] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Krishnan et al., 2021 [69] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Zahid et al., 2020 [70] |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murariu, A.; Bobu, L.; Gelețu, G.L.; Stoleriu, S.; Iovan, G.; Vasluianu, R.-I.; Foia, C.I.; Zapodeanu, D.; Baciu, E.-R. The Impact of Mobile Applications on Improving Oral Hygiene Knowledge and Skills of Adolescents: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2907. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092907

Murariu A, Bobu L, Gelețu GL, Stoleriu S, Iovan G, Vasluianu R-I, Foia CI, Zapodeanu D, Baciu E-R. The Impact of Mobile Applications on Improving Oral Hygiene Knowledge and Skills of Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(9):2907. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092907

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurariu, Alice, Livia Bobu, Gabriela Luminița Gelețu, Simona Stoleriu, Gianina Iovan, Roxana-Ionela Vasluianu, Cezar Ilie Foia, Diana Zapodeanu, and Elena-Raluca Baciu. 2025. "The Impact of Mobile Applications on Improving Oral Hygiene Knowledge and Skills of Adolescents: A Scoping Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 9: 2907. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092907

APA StyleMurariu, A., Bobu, L., Gelețu, G. L., Stoleriu, S., Iovan, G., Vasluianu, R.-I., Foia, C. I., Zapodeanu, D., & Baciu, E.-R. (2025). The Impact of Mobile Applications on Improving Oral Hygiene Knowledge and Skills of Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(9), 2907. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092907