Historical Gaps in the Integration of Patient-Centric Self-Management Components in HFrEF Interventions: An Umbrella Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

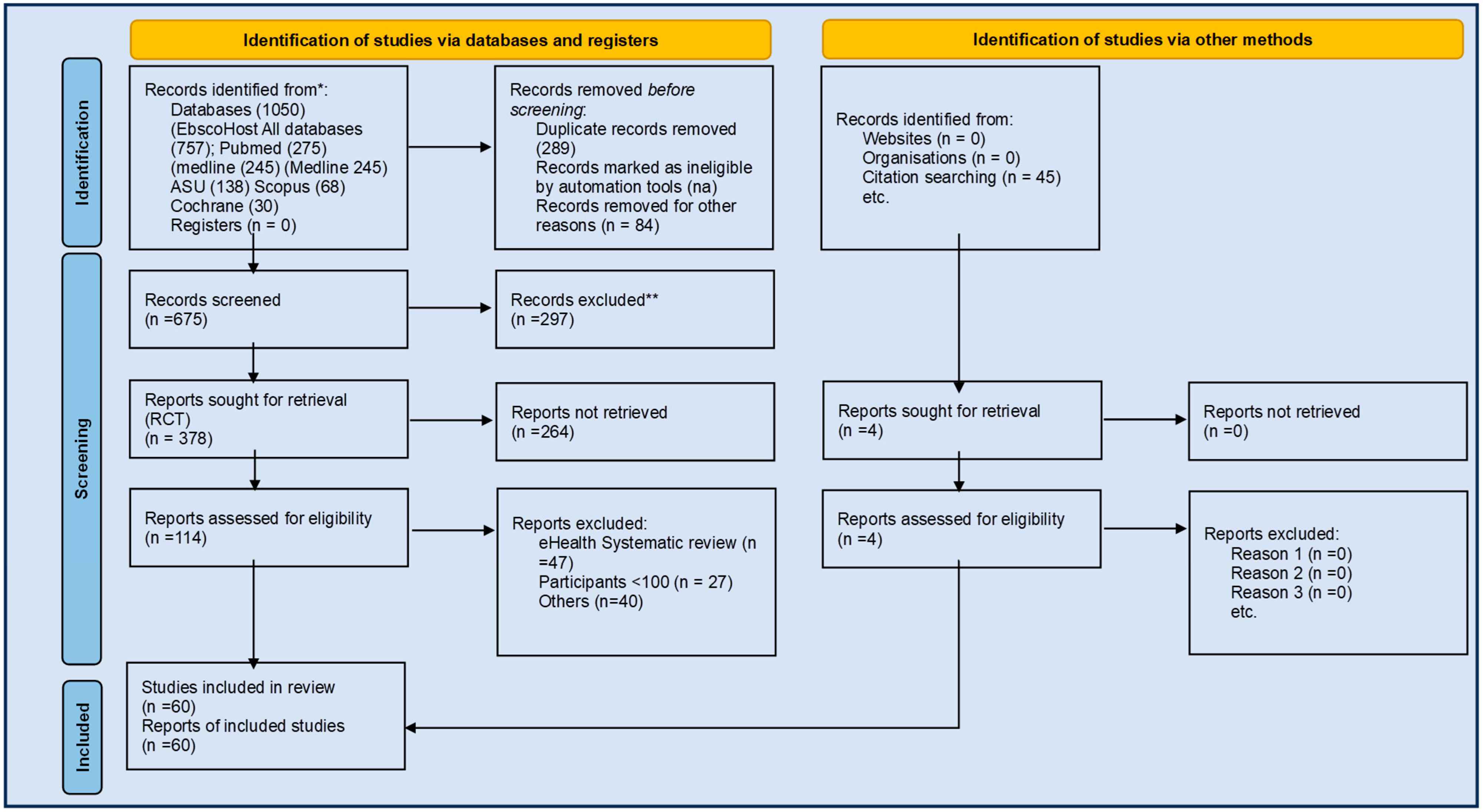

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Synthesis of Results

2.6. Definitions of Key Terms

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Umbrella Narrative Review

- i.

- Intervention Components

- ii.

- Outcome Measures

- iii.

- Frequency of Intervention Components

- iv.

- Outcome Reporting

3.3. Study Quality and Gaps

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychosocial Factors and Patient-Centered Care

4.2. Quality and Discernible Evidence

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author (Year) Country | Study | Intervention Content (IC) | Intervention Measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type, n | Participants Database | 1. Aims/2. Design/3. Population/4. Care Domains and Intensity | @ Delivery Domain 1. DF; 2. DP | Outcomes 1. Primary; 2. Secondary | ||

| Zhao et al., 2024 China [18] | SR RCT n = 19 | P-4681 R: 10–1518 FU: 3–12 m | Em, Md, Pb, SD, WS In to 2022 |

|

|

|

| Chen et al., 2023 Taiwan [19] | SR+MA RCT N = 13 | P = 2666 R: 28–197 FU: 2–24 m | CI, CL, Pb, Md 2002–22 |

|

|

|

| N’Li 2023 China [20] | SR+MA RCT N = 10 | P = NA R = NA FU 3–12 m | CE, CK, Eb, Pb, WoS In to 2022 |

|

|

|

| okYang 2023 Mly [21] | SR+MA RCT N = 105 | P = 37,607 R = NA FU 6–12 m | CL, Em, Ov, Pb In - 2022 |

|

|

|

| Hafkamp 2022 Holland [22] | USR SR+MA RCT N = 44/186 | P = 6101 R = 40–1650 FU: 3–34 m | CI, CL, Pb, PsI WoS 2011–2021 |

|

|

|

| Hsu 2022 Taiwan [23] | SR+MA RCT/Co N = 6/1 | N = 2346 R = 40–1937 FU: NA | CI, CL, CP, Em, Pb In - 2020 |

|

|

|

| Toback 2017 Canada [24] | SR RCT+NR N = 26 | NA | Pb, UP 1999–2016 |

|

|

|

| Taylor 2005 UK [25] | SR RCT N = 21 (16 RCT) | P = 1627 R: 34–1200 FU: 3–12 | Am, D, CI, CL, Em, Med; NHS, NRR, SCI; Si In - 2003 |

|

|

|

| Roccaforte 2005 Canada [26] | SR+MA RCT N = 33 | P = 7538 R = 34–1518 FU: 3–22 m | CL; Em; Med; Pb 1980–2004 |

|

|

|

| Gonseth 2004 Spain [27]/[88] | SR+MA RCT [21]/Co [21] N = 54 | P=>19030 R: 34–1966 FU: 1–50.4 m | CL, Em, Med 1966–2003 |

|

|

|

| Huang 2023 Taiwan [28] | SR+MA RCT N = 25 | P = 2746 R 40 to 228 FU: 1 w–12 m | CE, CI, Em, Med, PsI, WoS In to 2022 |

|

|

|

| Nwosu 2023 UK [29] | SR N = 18 | P = 2413 FU: 3–24 m | CI, Med, PsI, WoS In to 2022 |

|

|

|

| Checa 2022 Spain [30] | SR+MA RCT+QE, Co N = 30 | P = 8209 R-24 to 1894 FU: 1–12 m | CE, CL, CT, Em, ICTRP, Med, WHO In to 2022 |

|

|

|

| Huang 2022 Taiwan [31] | SR+MA RCT N = 24 | P = 2488 R-36 to 382 30 d–12 m | CE, CI, Em, Med, PsI, WoS In to 2021 |

|

|

|

| Ceu 2022 Portugal [32] | SR RCT [3], NRT N = 9 | NA | CI, Med |

|

|

|

| Imanuel Tonapa 2022 Taiwan [33] | SR+MA RCT N = 12 | P = 1938 R: 36–1437 2 m–12 m | CI, CL, Em, Med, Ov, Pb, WoS In to 2020 |

|

|

|

| Son 2020 Korea [34] | SR+MA RCT N = 8 | P = 1979 R: 88–412 3 m–12 m | CI, CL, Em, Pb, WoS 2000 to 2019 |

|

|

|

| Walsh 2017 Abs Conf Ireland [35] | SR RCT+NR N = 68 | NA | CI, Pb, Med, S 2006 to 2016 |

|

|

|

| Alnomasy 2023 USA [36] | SR+MA RCT N = 14 | P = 2035 R: 40–767 30 d–12 m | CL; NAHL; Pb; WoS (NA) |

|

|

|

| Mhanna 2023 USA [37] | SR+MA RCT N = 6 | P = 489 R: 41–158 30 d–12 m | CL; Em; Med; Pb In to 2022 |

|

|

|

| Olano-Lizarraga 2023 Spain [38] | SR RCT N = 8 | P = 1623 R: 64–468 30 d–12 m | CI; CL; Pb; PsI; SC; 2010 to 2022 |

|

|

|

| Nso 2023 Jamaica [39] | SR+MA RCT N = 9 | P = 1070 3–6 m | Pb; Sco, Wos |

|

|

|

| Balata 2023 Germany [40] | SR+MA RCT N = 7 | P = 611 R: 26–158 FU: 4–32 wk | CL, Pb, Sc, WoS (In to 2022) |

|

|

|

| Koikai 2023 Kenya [41] | SR RCT+NC N = 30 | P = 7685 R: 50–1223 FU: NA | CL, Em, GS Pb, SD 2012 to 2022 |

|

|

|

| Feng 2023 China [42] | SR+MA RCT N = 20 | P = 3459 R: 39–317 FU: 3–12 m | CK, Pb, WoS, VIP 1999 to 2022 |

|

|

|

| Nahlen Bose 2023 Sweden [43] | Meta-review (n = 7 SR) RCT = 67 | P = 10,132 R = 320 to 3837 FU: NA | CI, CL Pb, PsI In 2022 |

|

|

|

| Lee/Reigel 2022 USA [44] | MA RCT N = 27 | P = 6950 R = NA FU = NA | CI, Em, Pb, PsI 2008–2019 |

|

| SC knowledge and behavior, HRQOL |

| Villero-Jimenez 2022 Spain [45] | SR RCT+NC N = 12 | P = 1380 R = 19–369 FU = NA | CI, Pb, PsI (NA) |

|

|

|

| Ghizzardi 2022 Italy [46] | SR+MA RCT N = 9 | P = 1214 R-30 to 510 FU = 1–16 m | CI, Em, Pb PsI, Sc In to 2020 |

|

|

|

| Suksatan 2022 Thailand [47] | SR RCT+NC N = 15 | P = 10,701 R-36–2494 FU: 30 d | CI, CL, Pb, PsI, SC 2011 to 2022 |

|

|

|

| Meng 2021 China [48] | SR+MA RCT N = 8 | P = 1707 R: 20–902 FU:6–42 m | CL, CNKI, Em, Pb 2000 to 2020 |

|

|

|

| Tinoco 2021 Brazil [49] | SR+MA RCT+NR N = 19 | N = 1841 R:10–475 FU: NA | CI, LI, Pb, Sc (2012 to 2019) |

|

|

|

| Aghajanloo 2021 Iran [50] | SR+MA RCT+NR N = 39 | P = 8958 R: 17–2082 FU:NA | Em, GS, Ma, Pb, SID, WoS, 2004 to 2018 |

|

|

|

| Cañon-Montañez 2021 Colombia [51] | SR+MA RCT N = 45 | P = 9688 R: 37–1049 FU: 3–18 m | CI, CL, Em, Li, Pb, Sc, WoS (In to 2019) |

|

|

|

| Anderson 2021 UK [52] | SR RCT+QE N = 12 | P = 3887 R: 25–1023 FU: 3–24 m | BNI, CI, Em, Med (2008 to 2020) |

|

|

|

| Zhao 2021 China [53] | SR+MA RCT N = 15 | P = 2630 R: 28–475 FU: NA | CL, Em, Pb, WoS (In to 2019) |

|

|

|

| Poudel 2020 USA [54] | SR RCT+NR N = 8 | P = 758 R: 30–241 FU: NA | CI, CL, GS, HS, Med, PsI (1990 to 2019) |

|

|

|

| Świątoniowska-Lonc 2020 Poland [55] | SR+MA RCT N = 16 | P = 944 60–1160 FU: 1–18 m | Med, Pb, Sc (2010 to 2019) |

|

|

|

| Peng 2019 China [56] | SR+MA RCT N = 8 | P = 480 R: 17–158 FU: NA | CL, Em, Pb (In to 2018) |

|

|

|

| Parajuli 2019 Australia [57] | SR+MA RCT N = 18 | P = 4630 R:34 to 2169 FU: 3–55 m | CI, CL, Em, Med, Pb, SC, WoS (In to 2017) |

|

|

|

| Shanbhag 2018 Canada [58] | SR RCT+NR N = 38 | P = 76,582 R = 68–50,678 FU: NA | CI, CL, Em, Med 1990–2017 |

|

|

|

| Sterling 2018 USA [59] | SR RCT+NR N = 6 | P = 75,320 R-40–74,580 FU: 1–12 | AgeLine, CI, CL, Em, Med In-2017 |

|

|

|

| Jiang 2018 Taiwan [60] | SR+MA RCT N = 29 | P = 3837 R: 23–902 FU: NA | CI, CL, Em, Pb, PsI, SC, WoS, ProQ 2006–2016 |

|

|

|

| Jonkman 2016 Holland [61] | MA RCT N = 20 | P = 5624 R: 42–1023 FU: 3–18 | CI, CL, Em, Pb, PsI 1985–2013 |

|

|

|

| Ruppar 2016 USA [62] | SR+MA RCT+NC N = 57 | P = 4527 R:10–1518 FU: NA | CI, CL, D, IPA, Highw, Med, Sc, PQ In-2013 |

|

|

|

| Jonkman 2016 Holland [63] | SR+MA RCT N = 20 | P = 5624 R: 42–1023 FU: 3–18 | CI, CL, Em, Pb, PsI 1985–2013 |

|

|

|

| Srisuk 2016 Thailand [64] | SR RCT N = 9 | P = 666 R: 61–155 FU: 5–24 wk | CI, CL, Em, Med, Pb, PsI, Sc, WoS 2005–2015 |

|

|

|

| Ha Dinh 2016 Vietnam [65] | SR RCT+NR N = 12 | P = 467 R: 88–276 FU: 12–15 | CI, CL, Em Med, WoS In - 2013 |

|

|

|

| Inglis 2015 Australia [66] | SR+MA RCT N = 41 | P = 9332 R: var FU: var | Am, CE, DARE, HTA, Med, Em, CI, SCI, In - 2014 |

|

DF: All options

|

|

| Ruppar 2015 USA [67] | SR RCT+NR N = 29 | P = 4285 R: 10–902 FU: 1–24 | CI, CL, Em, Med In - 2013 |

|

|

|

| McGreal 2014 USA [80] | SR RCT N = 9 | P = 1415 R: 44–605 FU: 3–12 m | CI, Med, Pb, CINAHL, 2010–2014 |

|

|

|

| Casimir 2014 [68] | SR RCT NT = 7 | P =1260 R: 121–314 FU: 1–12 m | CEN, CI, CL, EM, ERIC, JBI, Med Inc to 2010 |

|

|

|

| Wakefield 2013 USA [69] | SR+MA RCT N = 43 | P = 8071 R: 25–1518 FU: 3–18 m | CI, CL, Med 1995–2008 |

|

|

|

| Barnason 2012 USA [70] | IR RCT N = 19 | P = 3166 R: 18–902 FU: 2–36 m | CI, CL, Med, PsI |

|

|

|

| Boyde 2011 USA [71] | SR RCT N = 19 | P = 2686 R: 36–314 FU: 3–18 m | CI, CL, Em, Med, PsI |

|

|

|

| Dickson 2011 USA [72] | MA RCT N = 3 | P = 99 R: NA FU: NA | Med, Pb |

|

|

|

| Yehle 2010 USA [73] | SR RCT+NR N = 12 | P = 1747 R: 20–801 FU: 1–12 m | CI, CL, ERIC, Med, Pb |

|

|

|

| Ditewig 2010 Holland [74] | SR RCT N = 19 | P = 4011 R: 50–766 FU: 6–24 m | CI, CL, Em, Med |

|

|

|

| Boren 2009 USA [75] | SR RCT N = 35 | P = 7413 R: NA FU: NA | CI, CL, Med |

|

|

|

| Jovicic 2006 Canada [76] | SR RCT N = 6 | P = 857 R: 70–223 FU: 3–12 m | ACP, CI, CL, Em, Med |

|

|

|

| McAlister 2004 Canada [77] | SR RCT N = 29 | P = 5039 R: 34–1396 FU: 1–12 | AMED, CI, CL, Em, Med |

|

|

|

- Case Management—Based on implementation of a collaborative process between one or more care coordinators or case managers and the patient, to assess, plan, and facilitate service delivery for patients with chronic diseases, particularly when transitions across healthcare settings are required.

- ○

- The Collaborative Health Management—is a model that builds on teamwork between the nurse practitioners and physicians, as an egalitarian partnership. Its long-term purpose is to operationalize Advanced Practice Registered Nurses to deliver high-quality chronic disease management.

- ○

- Transitional Care—The support provided to patients as they from one phase of disease or its management, such as from hospital-based care to home based care. This can involve both patients and families and with a range of medical emotional and other needs as they adjust and attain their care goals.

- ○

- Multicomponent Integrated Care—Coordination between different healthcare providers, providing patient education and self-management support, and facilitating smooth transitions between hospital and home care settings.

- ○

- Care Pathways—e.g., Telemonitoring, Structured telephone support, MDT clinic, cardiac care clinics (center based: individual or disease management programs; rehabilitation; community-based follow-up).

- Chronic Care Model—Model that identifies six modifiable elements of healthcare systems: (1) organizational support, addressing organizational culture and leadership, (2) clinical information systems to organize patient, population and provider data, (3) delivery system design to address composition and function of the care team and follow-up management, (4) decision support to increase provider access to evidence-based guidelines and specialists for collaboration, (5) self-management support to provide tailored education, skills training, psychosocial support and goal-setting, and (6) community resources to provide peer support, care coordination, and community-based interventions.

- Discharge Management—Interventions designed to facilitate effective transitions from hospital care to other settings. Typically includes a predischarge phase of support, transitional care for the move between the hospital and community/home setting, and post discharge follow-up and monitoring, often incorporating rehabilitation or reablement support.

- Complex Interventions—Two reviews assessed a range of interventions rather than focusing on a single intervention or service model.

- Multidisciplinary Team—Interventions comprising teams composed of multiple health and/or social care professionals working together to provide care for people with complex needs. Teams typically included condition-specific expertise, nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, social workers, GPs, and occasionally pharmacists or case managers.

- Disease Management—Six components: 1. Population identification process, 2. Evidence-based practice guideline, 3. Collaborative practice models, 4. Patient self-management education, 5. Process and outcome management, 6. Reporting and feedback loop.

References

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 1757–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegrante, J.P.; Wells, M.T.; Peterson, J.C. Interventions to Support Behavioral Self-Management of Chronic Diseases. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.M.; Savard, L.A.; Thompson, D.R. What Is the Strength of Evidence for Heart Failure Disease-Management Programs? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Fonarow, G.C.; Breathett, K.; Jurgens, C.Y.; Pisani, B.A.; Pozehl, B.J.; Spertus, J.A.; Taylor, K.G.; Thibodeau, J.T.; Yancy, C.W.; et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Clinical Performance and Quality Measures for Adults with Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2527–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaarsma, T.; Hill, L.; Bayes-Genis, A.; La Rocca, H.P.; Castiello, T.; Čelutkienė, J.; Marques-Sule, E.; Plymen, C.M.; Piper, S.E.; Riegel, B.; et al. Self-care of heart failure patients: Practical management recommendations from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toukhsati, S.R.; Jaarsma, T.; Babu, A.S.; Driscoll, A.; Hare, D.L. Self-Care Interventions That Reduce Hospital Readmissions in Patients with Heart Failure; Towards the Identification of Change Agents. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 2019, 13, 1179546819856855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyngkaran, P.; Buhler, M.; de Courten, M.; Hanna, F. Effectiveness of self-management programmes for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e079830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyngkaran, P.; Buhler, M.; McLachlan, C.; Gupta, B.; de Courten, M.; Hanna, F. Effectiveness of self-management programmes for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. ESC-HF, in process.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartling, L.; Ospina, M.; Liang, Y.; Dryden, D.M.; Hooton, N.; Krebs Seida, J.; Klassen, T.P. Risk of bias versus quality assessment of randomised controlled trials: Cross sectional study. BMJ 2009, 339, b4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2 (Updated February 2021). Available online: http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group. Available online: https://epoc.cochrane.org/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Iyngkaran, P.; Smith, D.; McLachlan, C.; Battersby, M.; De Courten, M.; Hanna, F. Validation of Psychometric Properties of Partners in Health Scale for Heart Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, T.; Kayling, F.; Miksch, A.; Szecsenyi, J.; Wensing, M. Effectiveness and efficiency of primary care based case management for chronic diseases: Rationale and design of a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized trials [CRD32009100316]. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepperd, S.; Lewin, S.; Straus, S.; Clarke, M.; Eccles, M.P.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Wong, G.; Sheikh, A. Can we systematically review studies that evaluate complex interventions? PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belbasis, L.; Bellou, V.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Conducting umbrella reviews. BMJ Med. 2022, 1, e000071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, S.; Luo, N.; Lin, Q.; Zhao, X.; Li, K. Care models for patients with heart failure at home: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 1295–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.W.; Lee, M.-C.; Wu, S.-F.V. Effects of a collaborative health management model on people with congestive heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 80, 2290–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y. Effect of Transitional Care Strategies on Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF): A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trails. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2023, 30, 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.-F.; Hoo, J.-X.; Tan, J.-Y.; Lim, L.-L. Multicomponent integrated care for patients with chronic heart failure: Systematic review and meta-analysis. ESC Heart Fail. 2023, 10, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafkamp, F.J.; Tio, R.A.; Otterspoor, L.C.; de Greef, T.; van Steenbergen, G.J.; van de Ven, A.R.; Smits, G.; Post, H.; van Veghel, D. Optimal effectiveness of heart failure management—An umbrella review of meta-analyses examining the effectiveness of interventions to reduce (re)hospitalizations in heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 1683–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-F.; Lee, S.-Y.; Hsu, T.-F.; Li, J.-Y.; Tung, H.-H. Patient Navigators for Transition Care of Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Gerontol. 2022, 16, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Toback, M.; Clark, N. Strategies to improve self-management in heart failure patients. Contemp. Nurse 2017, 53, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.; Bestall, J.; Cotter, S.; Falshaw, M.; Hood, S.G.; Parsons, S.; Wood, L.; Underwood, M. Clinical service organization for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 2, CD002752. [Google Scholar]

- Roccaforte, R.; Demers, C.; Baldassarre, F.; Teo, K.K.; Yusuf, S. Effectiveness of comprehensive disease management programmes in improving clinical outcomes in heart failure patients. A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2005, 7, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonseth, J.; Guallar-Castillón, P.; Banegas, J.R.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. The effectiveness of disease management programmes in reducing hospital re-admission in older patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published reports. Eur. Heart J. 2004, 25, 1570–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, T.; Gao, R.; Chair, S.Y. Effects of nurse-led self-care interventions on health outcomes among people with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 33, 1282–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwosu, W.O.; Rajani, R.; McDonaugh, T.; Goulder, A.; Smith, D.; Hughes, L. The impact of nurse-led patient education on quality of life in patients with heart failure. Br. J. Card. Nurs. 2023, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, C.; Canelo-Aybar, C.; Suclupe, S.; Ginesta-López, D.; Berenguera, A.; Castells, X.; Brotons, C.; Posso, M. Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Case Management in Advanced Heart Failure Patients Attended in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, T.; Chair, S.Y. Effectiveness of nurse-led self-care interventions on self-care behaviors, self-efficacy, depression and illness perceptions in people with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 132, 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Céu Sá, M.; Nabais, A. How to care for patients with heart failure—A systematic review of nursing interventions. New Trends Qual. Res. 2022, 11, e557. [Google Scholar]

- Imanuel Tonapa, S.; Inayati, A.; Sithichoksakulchai, S.; Daryanti Saragih, I.; Efendi, F.; Chou, F.H. Outcomes of nurse-led telecoaching intervention for patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.J.; Choi, J.; Lee, H.J. Effectiveness of Nurse-Led Heart Failure Self-Care Education on Health Outcomes of Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.C. A Nurse Led Clinic’s contribution to Patient Education and Promoting Self-care in Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2017, 17, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnomasy, N.; Still, C.H. Nonpharmacological Interventions for Preventing Rehospitalization Among Patients with Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. SAGE Open Nurs. 2023, 9, 23779608231209220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhanna, M.; Sauer, M.C.; Al-Abdouh, A.; Jabri, A.; Abusnina, W.; Safi, M.; Beran, A.; Mansour, S. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and metanalysis of randomized control trials. Heart Fail. Rev. 2023, 28, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olano-Lizarraga, M.; Wallström, S.; Martín-Martín, J.; Wolf, A. Interventions on the social dimension of people with chronic heart failure: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2023, 22, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nso, N.; Emmanuel, K.; Nassar, M.; Kaveh, R.B.; Daniel, A.-A.; Mohsen, A.; Ravali, K.; Ritika, K.; Sofia, L.; Vincent, R.; et al. Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiol. Rev. 2023, 31, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balata, M.; Gbreel, M.I.; Elrashedy, A.A.; Westenfeld, R.; Pfister, R.; Zimmer, S.; Nickenig, G.; Becher, M.U.; Sugiura, A. Clinical effects of cognitive behavioral therapy in heart failure patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koikai, J.; Khan, Z. The Effectiveness of Self-Management Strategies in Patients with Heart Failure: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e41863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Qu, Z.; Zheng, S. Effect of self-management intervention on prognosis of patients with chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 2015–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahlén Bose, C. A meta-review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on outcomes of psychosocial interventions in heart failure. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1095665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.S.; Westland, H.; Faulkner, K.M.; Iovino, P.; Thompson, J.H.; Sexton, J.; Farry, E.; Jaarsma, T.; Riegel, B. The effectiveness of self-care interventions in chronic illness: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 134, 104322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villero-Jiménez, A.I.; Martínez-Torregrosa, N.; Olano Lizarraga, M.; Garai-López, J.; Vázquez-Calatayud, M. Dyadic self-care interventions in chronic heart failure in hospital settings: A systematic review. An. Sist. Sanit. Navarra 2022, 45, e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghizzardi, G.; Arrigoni, C.; Dellafiore, F.; Vellone, E.; Caruso, R. Efficacy of motivational interviewing on enhancing self-care behaviors among patients with chronic heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksatan, W.; Tankumpuan, T. The Effectiveness of Transition Care Interventions from Hospital to Home on Rehospitalization in Older Patients with Heart Failure: An Integrative Review. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2022, 34, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Gu, J.; Fu, Y. Self-management on heart failure: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2021, 15, 102176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, J.D.M.V.P.; Figueiredo, L.D.S.; Flores, P.V.P.; Padua, B.L.R.D.; Mesquita, E.T.; Cavalcanti, A.C.D. Effectiveness of health education in the self-care and adherence of patients with heart failure: A meta-analysis. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2021, 29, e3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajanloo, A.; Negarandeh, R.; Janani, L.; Tanha, K.; Hoseini-Esfidarjani, S.S. Self-care status in patients with heart failure: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2235–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañon-Montañez, W.; Duque-Cartagena, T.; Rodríguez-Acelas, A.L. Effect of Educational Interventions to Reduce Readmissions due to Heart Failure Decompensation in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2021, 39, e05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.A.; Clemett, V. What impact do specialist and advanced-level nurses have on people living with heart failure compared to physician-led care? A literature review. J. Res. Nurs. 2021, 26, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Y.; Fan, X. Effects of self-management interventions on heart failure: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 116, 103909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel, N.; Kavookjian, J.; Scalese, M.J. Motivational Interviewing as a Strategy to Impact Outcomes in Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review. Patient 2020, 13, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świątoniowska-Lonc, N.A.; Sławuta, A.; Dudek, K.; Jankowska, K.; Jankowska-Polańska, B.K. The impact of health education on treatment outcomes in heart failure patients. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 29, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Fang, J.; Huang, W.; Qin, S. Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Heart Failure. Int. Heart J. 2019, 60, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, D.R.; Kourbelis, C.; Franzon, J.; Newman, P.; Mckinnon, R.A.; Shakib, S.; Whitehead, D.; Clark, R.A. Effectiveness of the Pharmacist-Involved Multidisciplinary Management of Heart Failure to Improve Hospitalizations and Mortality Rates in 4630 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Card. Fail. 2019, 25, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, D.; Graham, I.D.; Harlos, K.; Haynes, R.B.; Gabizon, I.; Connolly, S.J.; Van Spall, H.G.C. Effectiveness of implementation interventions in improving physician adherence to guideline recommendations in heart failure: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e017765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, M.R.; Shaw, A.L.; Leung, P.B.; Safford, M.M.; Jones, C.D.; Tsui, E.K.; Delgado, D. Home care workers in heart failure: A systematic review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2018, 11, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Shorey, S.; Seah, B.; Chan, W.X.; Tam, W.W.S.; Wang, W. The effectiveness of psychological interventions on self-care, psychological and health outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 78, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, N.H.; Westland, H.; Groenwold, R.H.; Ågren, S.; Anguita, M.; Blue, L.; de la Porte, P.W.F.B.-A.; DeWalt, D.A.; Hebert, P.L.; Heisler, M.; et al. What Are Effective Program Characteristics of Self-Management Interventions in Patients with Heart Failure? An Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. J. Card. Fail. 2016, 22, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppar, T.M.; Cooper, P.S.; Mehr, D.R.; Delgado, J.M.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.M. Medication Adherence Interventions Improve Heart Failure Mortality and Readmission Rates: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, N.H.; Westland, H.; Groenwold, R.H.; Ågren, S.; Atienza, F.; Blue, L.; de la Porte, P.W.B.-A.; DeWalt, D.A.; Hebert, P.L.; Heisler, M.; et al. Do Self-Management Interventions Work in Patients with Heart Failure? An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2016, 133, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srisuk, N.; Cameron, J.; Ski, C.F.; Thompson, D.R. Heart failure family-based education: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha Dinh, T.T.; Bonner, A.; Clark, R.; Ramsbotham, J.; Hines, S. The effectiveness of the teach-back method on adherence and self-management in health education for people with chronic disease: A systematic review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2016, 14, 210–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, S.C.; Clark, R.A.; Dierckx, R.; Prieto-Merino, D.; Cleland, J.G.F. Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD007228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppar, T.M.; Delgado, J.M.; Temple, J. Medication adherence interventions for heart failure patients: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 14, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casimir, Y.E.; Williams, M.M.; Liang, M.Y.; Pitakmongkolkul, S.; Slyer, J.T. The effectiveness of patient-centered self-care education for adults with heart failure on knowledge, self-care behaviors, quality of life, and readmissions: A systematic review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2014, 12, 188–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, B.J.; Boren, S.A.; Groves, P.S.; Conn, V.S. Heart failure care management programs: A review of study interventions and meta-analysis of outcomes. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 28, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnason, S.; Zimmerman, L.; Young, L. An integrative review of interventions promoting self-care of patients with heart failure. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 448–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyde, M.; Turner, C.; Thompson, D.R.; Stewart, S. Educational interventions for patients with heart failure: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2011, 26, E27–E35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, V.V.; Buck, H.; Riegel, B. A qualitative meta-analysis of heart failure self-care practices among individuals with multiple comorbid conditions. J. Card. Fail. 2011, 17, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehle, K.S.; Plake, K.S. Self-efficacy and educational interventions in heart failure: A review of the literature. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2010, 25, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditewig, J.B.; Blok, H.; Havers, J.; van Veenendaal, H. Effectiveness of self-management interventions on mortality, hospital readmissions, chronic heart failure hospitalization rate and quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 78, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boren, S.A.; Wakefield, B.J.; Gunlock, T.L.; Wakefield, D.S. Heart failure self-management education: A systematic review of the evidence. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2009, 7, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovicic, A.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.M.; Straus, S.E. Effects of self-management intervention on health outcomes of patients with heart failure: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2006, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlister, F.A.; Stewart, S.; Ferrua, S.; McMurray, J.J. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: A systematic review of randomized trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 810–819. [Google Scholar]

- Fonarow, G.C.; Abraham, W.T.; Albert, N.M.; Stough, W.G.; Gheorghiade, M.; Greenberg, B.H.; O’Connor, C.M.; Pieper, K.; Sun, J.L.; Yancy, C.; et al. Association between performance measures and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA 2007, 297, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toukhsati, S.R.; Driscoll, A.; Hare, D.L. Patient Self-management in Chronic Heart Failure—Establishing Concordance Between Guidelines and Practice. Card. Fail. Rev. 2015, 1, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreal, M.H.; Hogan, M.J.; Walsh-Irwin, C.; Maggio, N.J.; Jurgens, C.Y. Heart failure self-care interventions to reduce clinical events and symptom burden. Res. Rep. Clin. Cardiol. 2014, 5, 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Iyngkaran, P.; Smith, D.; McLachlan, C.; Battersby, M.; de Courten, M.; Hanna, F. Evaluating a New Short Self-Management Tool in Heart Failure Against the Traditional Flinders Program. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, V.; Robinson, S.; Marin-Link, B.; Underhill, L.; Dotts, A.; Ravensdale, D.R.; Salivaras, S. The expanded Chronic Care Model: An integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the Chronic Care Model. Hosp. Q. 2003, 7, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBain, H.; Shipley, M.; Newman, S. The impact of self-monitoring in chronic illness on healthcare utilisation: A systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, M.; De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; Di Palo, K.; Munir, H.; Music, S.; Piña, I.; Ringen, P.A. Severe Mental Illness and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 918–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernoff, R.A.; Messineo, G.; Kim, S.; Pizano, D.; Korouri, S.; Danovitch, I.; IsHak, W.W. Psychosocial Interventions for Patients with Heart Failure and Their Impact on Depression, Anxiety, Quality of Life, Morbidity, and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychosom Med. 2022, 84, 560–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White-Williams, C.; Rossi, L.P.; Bittner, V.A.; Driscoll, A.; Durant, R.W.; Granger, B.B.; Graven, L.J.; Kitko, L.; Newlin, K.; Shirey, M.; et al. Addressing Social Determinants of Health in the Care of Patients with Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e841–e863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, J.T.; Conway, C.; Babicheva, V.; Lee, C.S. Person with Heart Failure and Care Partner Dyads: Current Knowledge, Challenges, and Future Directions: State-of-the-Art Review. J. Card. Fail. 2023, 29, 1187–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.V.; Lavalle, C.; Palombi, M.; Pierucci, N.; Trivigno, S.; D’Amato, A.; Filomena, D.; Cipollone, P.; Laviola, D.; Piro, A.; et al. SGLT2i reduce arrhythmic events in heart failure patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. ESC Heart Fail. 2025; Early View. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Patient Education | Interventions aimed at increasing patient knowledge about their condition, including disease process, symptoms, and management strategies. |

| Self-Monitoring | The process of patients tracking their health status, such as weight, blood pressure, or symptoms, using tools like mobile health apps or written logs. |

| Goal Setting | Collaborative process where patients and providers set achievable, personalized goals related to managing their condition, such as medication adherence or lifestyle changes. |

| Self-Care Behaviors | Actions taken by patients to manage their condition, including medication adherence, symptom monitoring, physical activity, and dietary changes. |

| Telehealth | The use of digital communication platforms (e.g., phone calls, video conferencing) to provide healthcare services remotely, often used to support ongoing monitoring and education. |

| Era | * Outcome Measure | @Intervention Component | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | Hospitalizations | Self-Care Behaviors | Quality of Life | Patient Education | Self-Monitoring | Carer Goal-Setting | |

| UmbNR Post 2014 (n = 40) | 19/21 | 26/14 | 35/5 | 32/8 | 40/40 | 20/40 | 6/40 |

| Historical Gaps Pre 2014 (n = 20) | 13/7 | 13/7 | 17/3 | 15/5 | 20/20 | 12/20 | 5/20 |

| Frequency (%) | 47.5/65 | 65/65 | 87.5/85 | 80/75 | 100/100 | 50/60 | 15/25 |

| Author (Year); Country | Population Identification Process (>60 HF <40%) | Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines (>50% Describe Guidelines) | Collaborative Practice Models >50% | Patient Self-Management Education (Defined in >60% to <40%) | Process and Outcome Management (60> to >40% Protocols) | Reporting and Feedback Loop (Described in Study) | Strength of Evidence | Summary of Study Intervention | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao et al., 2024 China [18] | - | ~ | + | ++ | + | + | L | Case Management 4 MDT care models | HF population, care model not clear, FU variable |

| Chen et al., 2023 Taiwan [19] | - | ~ | ++ | - | + | + | L | Case Management Collaborative Health Management | HF Class provided but not HFrEF or HFpEF details |

| Li 2023 China [20] | ++ | ~ | + | - | ++ | + | L | Case Management Transitional Care | Minimal description of CDSM |

| Yang 2023 Mly [21] | + | ~ | + | - | + | + | L | Case Management Multicomponent Integrated Care | Limited description of models and processes |

| Hakams 2022 Holland [22] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Case Management Care Pathways | Umbrella SR. Includes all treatments 67/146 RCT on care pathway |

| Hsu 2022 Taiwan [23] | + | ~ | + | + | - | + | L | Case Management Patient Navigators | Many limitations in the pooling of information |

| Toback 2017 Canada [24] | - | ~ | + | + | - | - | L | Case Management Multiple SM support | Good SM information, but borderline criteria for SR and inclusion. |

| Taylor 2005 UK [25] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Case Management DMP (MDT, CMM, CM) | Multiple disease management models. Indeterminate |

| Roccaforte 2005 Canada [26] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Case Management DMP | DMP improve MACE. |

| Gonseth 2004 Spain [27] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Case Management DMP—elderly | DMP improve MACE esp. elderly. |

| Huang 2023 China [28] | - | ~ | + | + | - | - | M | Nurse-Led SM | Poorly descriptive meta-analysis |

| Nwosu 2023 UK [29] | - | ~ | + | - | - | - | L | Nurse-Led Patient Education | Poorly descriptive. Outcomes data focus |

| Checa 2022 Spain [30] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Nurse-Led Case management primary care | Primary care study with cost-effectiveness |

| Huang 2022 China [31] | - | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Nurse-Led SM | Good study. HF diagnosis is not clear. |

| Ceu 2022 Portugal [32] | - | ~ | - | - | - | - | VL | Nurse-Led Variable nursing interventions | Brief general discussion on studies. |

| Imanuel Tonapa 2022 Taiwan [33] | ++ | ~ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | M | Nurse-Led Telecoaching | Self-management programs not well described. |

| Son 2020 Sth Korea [34] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Nurse-Led SM education | Good study. Minor gaps for high grade. |

| Walsh 2017 Ireland [35] | - | ~ | - | + | - | - | L | Nurse-Led Clinic based SM education | Limited information in many areas. |

| Alnomasy 2023 USA [36] | - | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | M | Non-Pharmacological Ambulatory—home visits, phone calls, digital platforms, technologies. | HF not well characterized. |

| Mhanna 2023 USA [37] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological CBT | Depression focus on CDSM. |

| Olano-Lizarraga 2023 Spain [38] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological Interventions targeting the social dimension | Good study. Minor gaps for high grade |

| Nso 2023 USA [39] | - | ~ | + | + | - | - | L | Non-Pharmacological CBT | Poorly descriptive. Outcomes data focus |

| Balata 2023 Germany [40] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological CBT | Good study. Depression focus. |

| Koikai 2023 UK [41] | + | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological SM education strategies | Some studies did not report HF grade adequately. |

| Feng 2023 China [42] | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological SM intervention strategies | Only study to describe guideline utilized. |

| Nahlen Bose 2023 Sweden [43] | - | ~ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological Psychosocial Interventions | Good study some gaps in HF and SM details. |

| Lee 2022 USA [44] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological SM intervention | Excellent focused, some data extrapolated from citation. |

| Villero-Jimenez 2022 Spain [45] | + | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological Dyadic SM interventions | Spanish translated. Gaps in HF details |

| Ghizzardi 2022 Italy [46] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological Motivational interviewing on SM | Focus on delivery programs. |

| Suksatan 2022 Thailand [47] | + | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological Transitional Care Intervention elderly | Excellent description of care programs. HF details lacking. |

| Meng 2021 China [48] | - | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological SM intervention | Covered all domains, but studies specifics lacking. |

| Tinoco 2021 Brazil [49] | - | ~ | ++ | ++ | - | - | L | Non-Pharmacological Health education and SM | Scoping nature, limited details. |

| Aghajanloo 2021 Iran [50] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological SM behaviors with SCHFI | Good description on CDSM. |

| Cañon-Montañez 2021 Colombia [51] | - | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological Educational Intervention | Superficially covers all domains. |

| Anderson 2021 UK [52] | - | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | L | Non-Pharmacological Advanced-level nurses specialist nurse-led vs. physician-led | It covers broad areas superficially. |

| Zhao 2021 China [53] | - | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological SM interventions | Excellent study, few HF details. |

| Poudel 2020 USA [54] | - | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological Motivational interviewing | Covers relevant domains. |

| Świątoniowska-Lonc 2020 Poland [55] | ++ | ~ | ++ | + | + | ++ | VL | Non-Pharmacological Health Education | It covers many domain in very superficial detail. |

| Peng 2019 China [56] | ++ | ~ | + | + | + | ++ | L | Non-Pharmacological CBT | Focused area, outcomes strong point. |

| Parajuli 2019 Australia [57] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological Pharmacist Involved MDT | High quality study, few flaws. |

| Shanbhag 2018 Canada [58] | - | ~ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | L | Non-Pharmacological Interventions improving physician adherence to guideline | Variable study design. Poor HF description. |

| Sterling 2018 USA [59] | - | ~ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | L | Non-Pharmacological Home Care Workers | Missing important data. |

| Jiang 2018 Taiwan [60] | - | ~ | + | + | + | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological SM Psychological Interventions | Good study, focus on meta-analyses. Domain description reduced. |

| Jonkman 2016 Holland [61] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological SM, program details | Gold-standard. |

| Ruppar 2016 USA [62] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological Medication adherence. | Detailed, informing study. |

| Jonkman 2016 Holland [63] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological SM interventions | Gold-standard |

| Srisuk 2016 Thailand [64] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | L | Non-Pharmacological Family based education | Detailed. Quality influenced by grading criteria |

| Ha Dinh 2016 Vietnam [65] | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | L | Non-Pharmacological Teach-back method, SM | Detailed study. Technical gaps. |

| Inglis 2015 Australia [66] | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological Structured Telephone support, telemonitoring | Gold standard. |

| Ruppar 2015 USA [67] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological Medication adherence | Covers an important topic. |

| Casimir 2014 USA [68] | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological Patient centered SM | Comprehensive. |

| Wakefield 2013 USA [69] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological Care Management Program | Descriptive. |

| Barnason 2012 USA [70] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological SM Interventions | Few flaws, grading based on scoring system. |

| Boyde 2011 USA [71] | - | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | M | Non-Pharmacological Educational Interventions | Good SM study, details on HF lacking. |

| Dickson 2011 USA [72] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological SM Practices | Very limited high quality hypothesis generating study. |

| Yehle 2010 USA [73] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological Educational Interventions | Good SM study. |

| Ditewig 2010 Holland [74] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological SM Interventions | Good SM study. |

| Boren 2009 USA [75] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological SM education | Good SM study. |

| Jovicic 2006 Canada [76] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological SM intervention | Good SM study. |

| McAlister 2004 Canada [77] | ++ | ~ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | H | Non-Pharmacological Multidisciplinary strategies | Good SM study. |

| Author (Year) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao et al., 2024 [18] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | PY | Y | N | N-MA | N-MA | N | N | N-MA | Y | L |

| Chen et al., 2023 Tai [19] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Li China 2023 [20] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y RCT | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | L |

| Yang Mly 2023 [21] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y RCT | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Hafkamp 2022 [22] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Hsu 2022 [23] L-Ch | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | PY | N | Y | L |

| Toback 2017 [24] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y RCT | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Taylor 2005 [25] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Roccaforte 2005 [26] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Gonseth 2004 [27] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Huang 2023 [28] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Nwosu 2023 [29] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | PY | N | Y | L |

| Checa 2022 [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Huang 2022 [31] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y RCT | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Ceu 2022 [32] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | N BOTH | N | N BOTH | N-MA | N | N | N-MA | N | VL |

| Imanuel Tonapa 2022 [33] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | PY RCT | N | Y RCT | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Son 2020 [34] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | M |

| Walsh 2017 [35] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | N | N | PY | N BOTH | N | N-MA | N-MA | N | N | N-MA | N | L |

| Alnomasy 2023 [36] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Mhanna 2023 [37] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Olano-Lizarraga 2023 [38] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y RCT | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | M |

| Nso 2023 [39] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y RCT | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Balata 2023 [40] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y RCT | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Koikai 2023 [41] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y BOTH | N | N | N-MA | N | N | N | Y | M |

| Feng 2023 [42] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Nahlen Bose 2023 [43] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | N | Y | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Lee/Reigel 2022 [44] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | PY | Y RCT | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Villero-Jimenez 2022 [45] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Ghizzardi 2022 [46] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Suksatan 2022 [47] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y BOTH | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| 2021 Meng [48] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | PY | PY RCT | Y | Y RCT | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Tinoco 2021 [49] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | PY | PY RCT | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Aghajanloo 2021 [50] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y NRSI | N | Y BOTH | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Cañon-Montañez 2021 [51] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Anderson 2021 [52] | Y | PY | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y BOTH | N | N BOTH | N MA | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | |

| Zhao 2021 [53] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | PY RCT | N | Y RCT | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Poudel 2020 [54] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Świątoniowska-Lonc 2020 [55] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | PY RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | N-MA | Y | VL |

| Peng 2019 [56] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | L |

| Parajuli 2019 [57] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Shanbhag 2018 [58] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y BOTH | N | N-MA | N-MA | Y | Y | N-MA | Y | L |

| Sterling 2018 [59] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y NRSI | Y | N-MA | N-MA | Y | Y | N | Y | L |

| Jiang 2018 [60] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Jonkman 2016 [61] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Ruppar 2016 [62] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | N | Y | Y RCT | N | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Jonkman 2016 [63] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Srisuk 2016 [64] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y RCT | Y | N-MA | N-MA | Y | Y | N-MA | Y | L |

| Ha Dinh 2016 [65] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y BOTH | N | N MA | N MA | Y | Y | N-MA | Y | L |

| Inglis 2015 [66] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y RCT | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H | |

| Ruppar 2015 [67] | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Casimir [68] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | PY | Y RCT | N | N-MA | N-MA | Y | N | N-MA | Y | M |

| Wakefield 2013 [69] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Barnason 2012 [70] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y RCT/PY NRSI | Y | Y BOTH | Y | Y | N | N | Y | M |

| Boyde 2011 [71] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | M |

| Dickson 2011 [72] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Yehle 2010 [73] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Ditewig 2010 [74] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y RCT | N | N-MA | N-MA | Y | Y | N-MA | Y | H |

| Boren 2009 [75] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Jovicic 2006 [76] | Y | PY | Y | Y | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| McAlister 2004 [77] | Y | PY | Y | PY | Y | Y | PY | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y RCT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iyngkaran, P.; Fazli, F.; Nguyen, H.; Patel, T.; Hanna, F. Historical Gaps in the Integration of Patient-Centric Self-Management Components in HFrEF Interventions: An Umbrella Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2832. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082832

Iyngkaran P, Fazli F, Nguyen H, Patel T, Hanna F. Historical Gaps in the Integration of Patient-Centric Self-Management Components in HFrEF Interventions: An Umbrella Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(8):2832. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082832

Chicago/Turabian StyleIyngkaran, Pupalan, Fareda Fazli, Hayden Nguyen, Taksh Patel, and Fahad Hanna. 2025. "Historical Gaps in the Integration of Patient-Centric Self-Management Components in HFrEF Interventions: An Umbrella Narrative Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 8: 2832. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082832

APA StyleIyngkaran, P., Fazli, F., Nguyen, H., Patel, T., & Hanna, F. (2025). Historical Gaps in the Integration of Patient-Centric Self-Management Components in HFrEF Interventions: An Umbrella Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(8), 2832. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082832