Sexual Dysfunction in Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

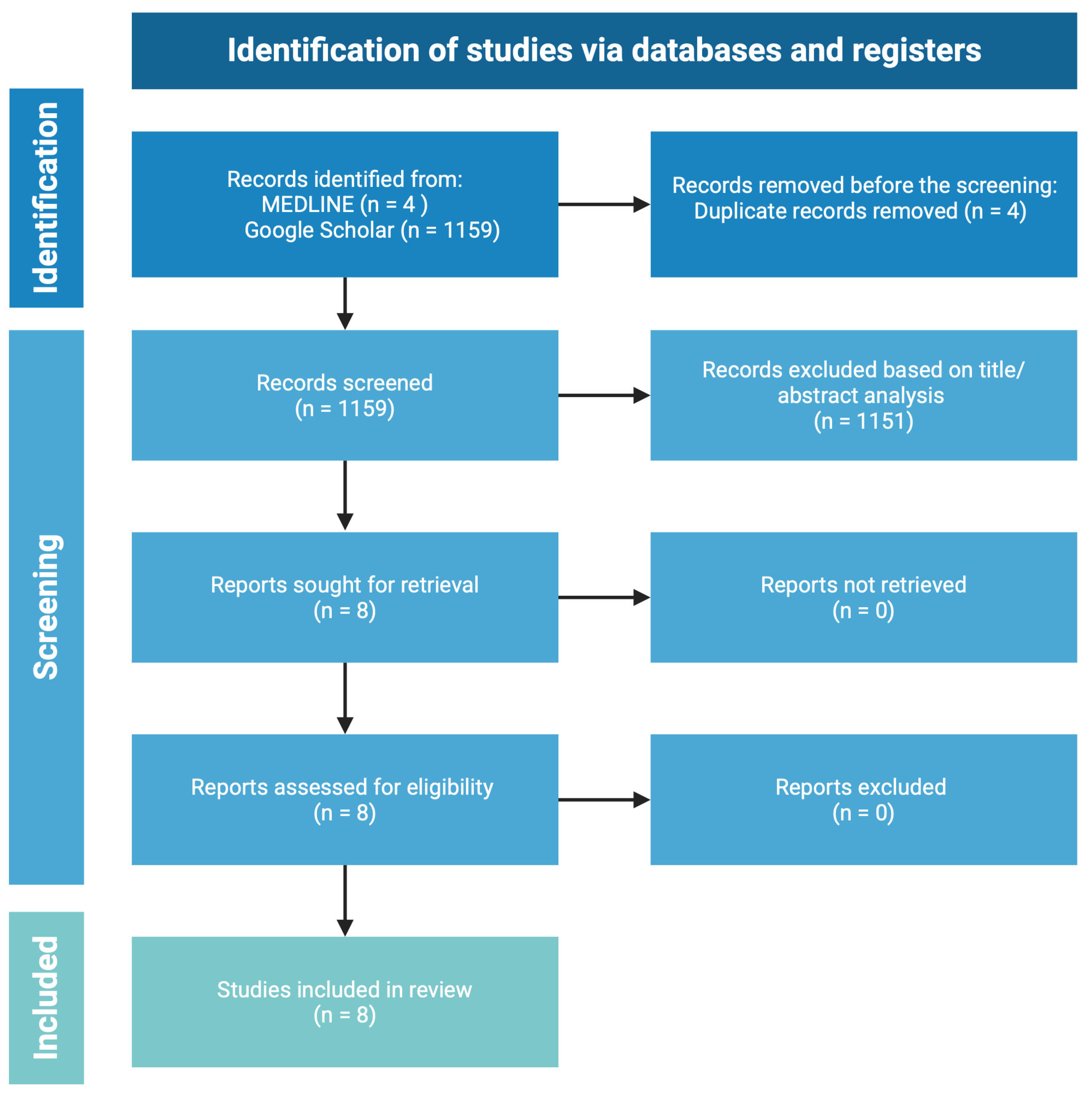

2. Methodology and Search Strategy

3. Alopecia Areata (AA)

3.1. Sexual Health

3.2. The Association Between Sexual and Mental Health

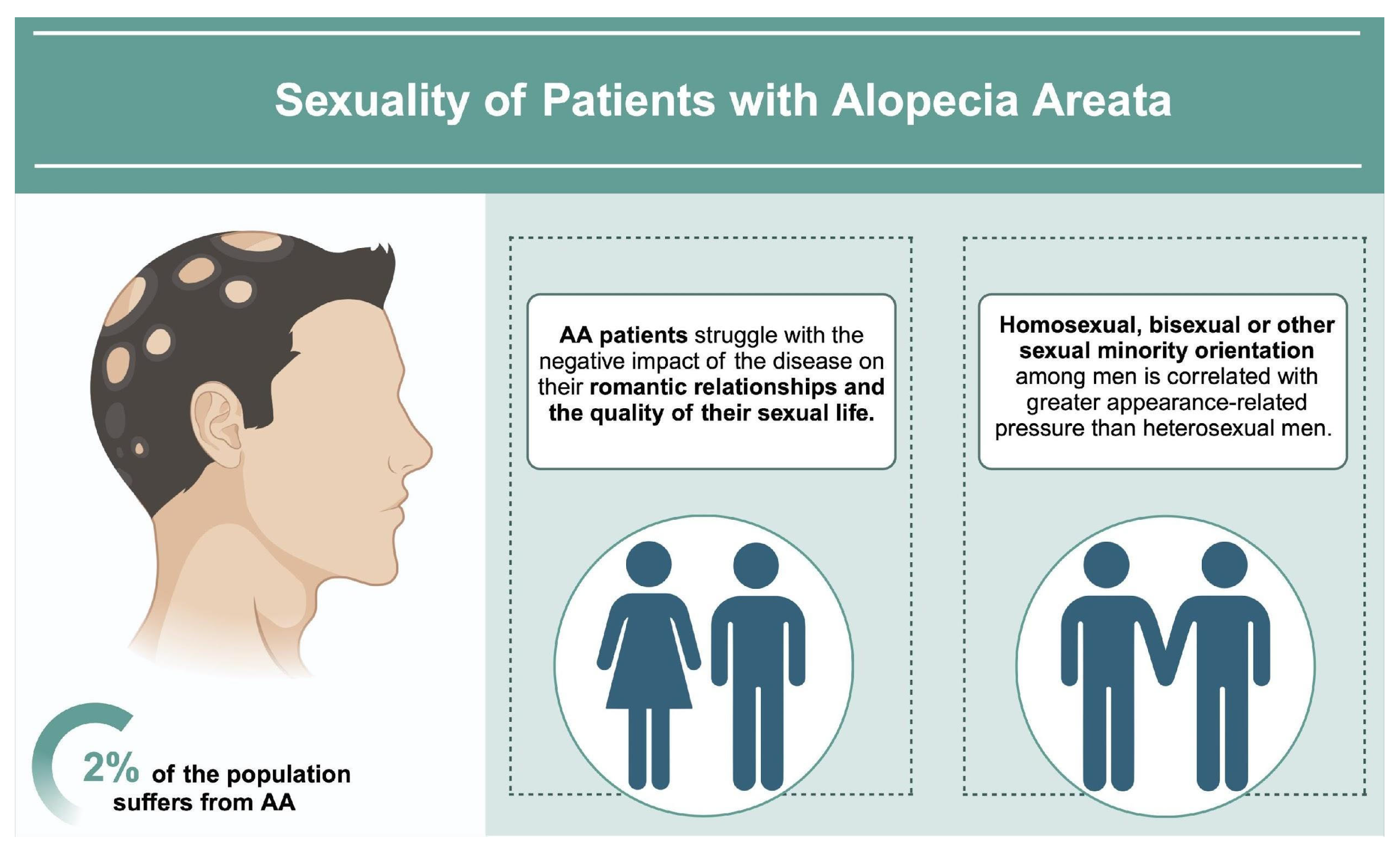

3.3. Sexuality of AA Patients

3.4. Impact of Alopecia Areata Treatment on Sexual Health

4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Alopecia areata |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| SD | Sexual dysfunction |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-γ |

| SQol-F | Sexual Quality of Life-Female |

| FSFI | Female Sexual Function Index |

| FSDS | Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS). |

| SQoL-M | Sexual Quality of Life-Male |

| IIEF | International Index of Erectile Function |

| MSHQ | Male Sexual Health Questionnaire |

| PD | Psychiatric disorders |

| Il-1 | Interleukin 1 |

| Il-4 | Interleukin 4 |

| Il-13 | Interleukin 13 |

| ED | Erectile dysfunction |

| AGA | Androgenetic alopecia |

References

- Lepe, K.; Syed, H.A.; Zito, P.M. Alopecia Areata. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sibbald, C. Alopecia Areata: An Updated Review for 2023. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2023, 27, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haughton, R.D.; Herbert, S.M.; Ji-Xu, A.; Downing, L.; Raychaudhuri, S.P.; Maverakis, E. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata: A narrative review. Indian. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2023, 89, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lintzeri, D.A.; Constantinou, A.; Hillmann, K.; Ghoreschi, K.; Vogt, A.; Blume-Peytavi, U. Alopecia areata—Current understanding and management. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2022, 20, 59–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuyama, M.; Ito, T.; Ohyama, M. Alopecia areata: Current understanding of the pathophysiology and update on therapeutic approaches, featuring the Japanese Dermatological Association guidelines. J. Dermatol. 2022, 49, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsantali, A. Alopecia areata: A new treatment plan. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 4, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, M.; Richter-Appelt, H.; Tosti, A.; Viera, M.S.; García, M. The psychosocial impact of hair loss among men: A multinational European study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2005, 21, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münstedt, K.; Manthey, N.; Sachsse, S.; Vahrson, H. Changes in self-concept and body image during alopecia induced cancer chemotherapy. Support. Care Cancer. 1997, 5, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemmesen, M.E.R.; Gren, S.T.; Frøstrup, A.G.; Thomsen, S.F.; Egeberg, A.; Thein, D. Psychosocial and mental impact of alopecia areata: Analysis of the Danish Skin Cohort. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasante Fricke, A.C.; Miteva, M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: A systematic review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 8, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuty-Pachecka, M. Psychological and psychopathological factors in alopecia areata. Psychiatr. Pol. 2015, 49, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoy, M.; O’Gurek, D.; Brown-James, A. Sexual Health History: Techniques and Tips. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 101, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Huang, D.-D.; Li, Y.; Ma, C.-C.; Shi, M.; Su, B.-X.; Shi, G.-J. Male sexual dysfunction: A review of literature on its pathological mechanisms, potential risk factors, and herbal drug intervention. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narang, T.; Garima Singh, S.M. Psychosexual disorders and dermatologists. Indian. Dermatol. Online J. 2016, 7, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, V.; Frasier, K.; Fritts, H.; Stech, K.; Grant, C.; Loperfito, A. Exploring the Psychosexual Impact of Dermatological Conditions and the Path Towards Integrated Interventions. Am. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2024, 441, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendke, M.; Kanti-Schmidt, V.; Wilborn, D.; Hillmann, K.; Singh, R.; Vogt, A.; Kottner, J.; Blume-Peytavi, U. Quality of life in children and adolescents with alopecia areata-A systematic review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 1521–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, C.H.; King, L.E., Jr.; Messenger, A.G.; Christiano, A.M.; Sundberg, J.P. Alopecia areata. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pellicer, P.; Navarro-Moratalla, L.; Núñez-Delegido, E.; Agüera-Santos, J.; Navarro-López, V. How Our Microbiome Influences the Pathogenesis of Alopecia Areata. Genes 2022, 13, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserman, D.; Guzman-Sanchez, D.A.; Scott, K.; McMichael, A. Alopecia areata. Int. J. Dermatol. 2007, 46, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.L.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Peeva, E. Pathogenesis of Alopecia Areata and Vitiligo: Commonalities and Differences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wan, S.; Xie, B.; Song, X. Novel potential therapeutic targets of alopecia areata. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1148359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spano, F.; Donovan, J.C. Alopecia areata: Part 1: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and prognosis. Can. Fam. Physician 2015, 61, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alhanshali, L.; Buontempo, M.G.; Lo Sicco, K.I.; Shapiro, J. Alopecia Areata: Burden of Disease, Approach to Treatment, and Current Unmet Needs. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juárez-Rendón, K.J.; Rivera Sánchez, G.; Reyes-López, M.Á.; E García-Ortiz, J.; Bocanegra-García, V.; Guardiola-Avila, I.; Altamirano-García, M.L. Alopecia Areata. Current situation and perspectives. Alopecia areata. Actual. Y Perspect. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2017, 115, e404–e411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minokawa, Y.; Sawada, Y.; Nakamura, M. Lifestyle Factors Involved in the Pathogenesis of Alopecia Areata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.H.C.; Sallee, B.N.; Tejeda, C.I.; Christiano, A.M. JAK Inhibitors for Treatment of Alopecia Areata. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1911–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaioli, D.; Ciocca, G.; Limoncin, E.; Di Sante, S.; Gravina, G.L.; Carosa, E.; Lenzi, A.; Jannini, E.A.F. Lifestyles and sexuality in men and women: The gender perspective in sexual medicine. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2020, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Glover, J.; Tampi, R.R.; Tampi, D.J.; Sewell, D.D. Sexuality and the Older Adult. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.M., Jr.; Fenton, K.A. Understanding sexual health and its role in more effective prevention programs. Public. Health Rep. 2013, 128 (Suppl. S1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzimouratidis, K.; Hatzichristou, D. Sexual dysfunctions: Classifications and definitions. J. Sex. Med. 2007, 4, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman, J.R. Sexual dysfunction: Overview of prevalence, etiological factors, and treatments. J. Sex. Res. 2002, 39, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, L.P. Management of sexual disorders. Singapore Med. J. 1993, 34, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kingsberg, S.A.; Knudson, G. Female sexual disorders: Assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. CNS Spectr. 2011, 16, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.; Laforge, J.; Ross, M.M.; Vanlangendonck, R.; Hasoon, J.; Viswanath, O.; Kaye, A.D.; Urits, I. Male Sexual Dysfunction. Health Psychol. Res. 2022, 10, 37533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.J.; Tzeng, N.S.; Chung, C.H.; Chien, W.C. Psychiatric disorders in female psychosexual disorders-a nationwide, cohort study in Taiwan: Psychiatric disorders and female psychosexual disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avasthi, A.; Grover, S.; Sathyanarayana Rao, T.S. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Sexual Dysfunction. Indian. J. Psychiatry 2017, 59 (Suppl. S1), S91–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, A.; Matthiesen, S.; Cerwenka, S.; Otten, M.; Briken, P. Health, Sexual Activity, and Sexual Satisfaction. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2020, 117, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, N.; Mercer, C.H.; Sonnenberg, P.; Tanton, C.; Clifton, S.; Mitchell, K.R.; Erens, B.; Macdowall, W.; Wu, F.; Datta, J.; et al. Associations between health and sexual lifestyles in Britain: Findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet 2013, 382, 1830–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, K.E.; Lin, L.; Bruner, D.W.; Cyranowski, J.M.; Hahn, E.A.; Jeffery, D.D.; Reese, J.B.; Reeve, B.B.; Shelby, R.A.; Weinfurt, K.P. Sexual Satisfaction the Importance of Sexual Health to Quality of Life Throughout the Life Course of, U.S. Adults. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampogna, F.; Abeni, D.; Gieler, U.; Tomas-Aragones, L.; Lien, L.; Titeca, G.; Jemec, G.; Misery, L.; Szabó, C.; Linder, M.; et al. Impairment of Sexual Life in 3,485 Dermatological Outpatients From a Multicentre Study in 13 European Countries. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2017, 97, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisone, M.; Bagnasco, A.; Hayter, M.; Rossi, S.; Aleo, G.; Zanini, M.; Catania, G.; Pellegrini, R.; Dasso, N.; Ghirotto, L.; et al. Dermatological diseases, sexuality and intimate relationships: A qualitative meta-synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 3136–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauendorffer, J.N.; Ly, S.; Beylot-Barry, M. Psoriasis and male sexuality. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 146, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim-Sim, M.; Aaberg, V.; Gómez-Cantarino, S.; Dias, H.; Caldeira, E.; Soto-Fernandez, I.; Gradellini, C. Sexual Quality of Life-Female (SQoL-F): Cultural Adaptation and Validation of European Portuguese Version. Healthcare 2022, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janik, M.R.; Bielecka, I.; Paśnik, K.; Kwiatkowski, A.; Podgórska, L. Female Sexual Function Before and After Bariatric Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Study and Review of Literature. Obes. Surg. 2015, 25, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacik, P.T.; Geletta, S. Vaginismus Treatment: Clinical Trials Follow Up 241 Patients. Sex. Med. 2017, 5, e114–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.S.; Reed, S.D.; Guthrie, K.A.; Larson, J.C.; Newton, K.M.; Lau, R.J.; Learman, L.A.; Shifren, J.L. Using an FSDS-R Item to Screen for Sexually Related Distress: A MsFLASH Analysis. Sex. Med. 2015, 3, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maasoumi, R.; Mokarami, H.; Nazifi, M.; Stallones, L.; Taban, A.; Aval, M.Y.; Samimi, K. Psychometric Properties of the Persian Translation of the Sexual Quality of Life-Male Questionnaire. Am. J. Mens. Health 2017, 11, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.C.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Smith, M.D.; Lipsky, J.; Peña, B.M. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int. J. Impot. Res. 1999, 11, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrborn, C.G.; Rosen, R.C.; Manyak, M.J.; Palacios-Moreno, J.M.; Wilson, T.H.; Lulic, Z.; Giuliano, F. Men’s Sexual Health Questionnaire score changes vs spontaneous sexual adverse event reporting in men treated with dutasteride/tamsulosin combination therapy for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia: A post hoc analysis of a prospective, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 74, e13480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejo, A.L. Sexuality and Mental Health: The Need for Mutual Development and Research. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macbeth, A.E.; Holmes, S.; Harries, M.; Chiu, W.S.; Tziotzios, C.; de Lusignan, S.; Messenger, A.G.; Thompson, A.R. The associated burden of mental health conditions in alopecia areata: A population-based study in UK primary care. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 187, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herder, T.; Spoelstra, S.K.; Peters, A.W.M.; Knegtering, H. Sexual dysfunction related to psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. J. Sex. Med. 2023, 20, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, S.H.; Rizvi, S. Sexual dysfunction, depression, and the impact of antidepressants. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 29, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K.; Reynolds, M.F. Sexual dysfunction in major depression. CNS Spectr. 2006, 11 (Suppl. S9), 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, N.; Prah, P.; Mercer, C.H.; Rait, G.; King, M.; A Cassell, J.; Tanton, C.; Heath, L.; Mitchell, K.R.; Clifton, S.; et al. Are depression and poor sexual health neglected comorbidities? Evidence from a population sample. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H.S. Anxiety and sexual dysfunction. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1988, 49, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lapping-Carr, L.; Mustanski, B.; Ryan, D.T.; Costales, C.; Newcomb, M.E. Stress and Depression Are Associated with Sexual Function and Satisfaction in Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2023, 52, 2083–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenmann, G.; Atkins, D.C.; Schär, M.; Poffet, V. The association between daily stress and sexual activity. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.A.; Gupta, A.K.; Watteel, G.N. Stress and alopecia areata: A psychodermatologic study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1997, 77, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonul, M.; Cemil, B.C.; Ayvaz, H.H.; Cankurtaran, E.; Ergin, C.; Gurel, M.S. Comparison of quality of life in patients with androgenetic alopecia and alopecia areata. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2018, 93, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krefft-Trzciniecka, K.; Cisoń, H.; Pakiet, A.; Nowicka, D.; Szepietowski, J.C. Enhancing Quality of Life and Sexual Functioning in Female Androgenetic Alopecia: Therapeutic Potential of Hair Follicle-Derived Stem Cells. Healthcare 2024, 12, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.J.; Huang, K.P.; Joyce, C.; Mostaghimi, A. The Impact of Alopecia Areata on Sexual Quality of Life. Int. J. Trichol. 2018, 10, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Barba, D.; Díaz-Calvillo, P.; de Francisco, S.H.; Martínez-Lopez, A.; Sánchez-Díaz, M.; Arias-Santiago, S. Comparative study on sexual dysfunction in alopecia areata: Prevalence and associated factors. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Díaz, M.; Díaz-Calvillo, P.; Soto-Moreno, A.; Molina-Leyva, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. The Impact of Sleep Quality on Mood Status and Quality of Life in Patients with Alopecia Areata: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 13126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.J.; Mesinkovska, N.; Kranz, D.; Ellison, A.; Senna, M.M. Cumulative Life Course Impairment of Alopecia Areata. Int. J. Trichol. 2020, 12, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Díaz, M.; Díaz-Calvillo, P.; Ureña-Paniego, C.A.; Molina-Leyva, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Quality of Life and Mood Status Disturbances in Cohabitants of Patients with Alopecia Areata: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Spanish Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 16323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Y.; King, B.A.; Craiglow, B.G. Alopecia areata is associated with impaired health-related quality of life: A survey of affected adults and children and their families. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 79, 556–558.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhouse, N.V.J.; Kitchen, H.; Knight, S.; Macey, J.; Nunes, F.P.; Dutronc, Y.; Mesinkovska, N.; Ko, J.M.; King, B.A.; Wyrwich, K.W. “‘You lose your hair, what’s the big deal?’ I was so embarrassed, I was so self-conscious, I was so depressed:” a qualitative interview study to understand the psychosocial burden of alopecia areata. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2020, 4, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntyanu, A.; Gabrielli, S.; Donovan, J.; Gooderham, M.; Guenther, L.; Hanna, S.; Lynde, C.; Prajapati, V.H.; Wiseman, M.; Netchiporouk, E. The burden of alopecia areata: A scoping review focusing on quality of life, mental health and work productivity. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 1490–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.C.; Lee, E.S.; Choi, J.W. Impact of alopecia areata on psychiatric disorders: A retrospective cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldmeadow, J.A.; Dixson, B.J. The Association Between Men’s Sexist Attitudes and Facial Hair. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordes, M.; Vocks, S.; Hartmann, A.S. Appearance-Related Partner Preferences and Body Image in a German Sample of Homosexual and Heterosexual Women and Men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 3575–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucchelli, F.; Mathews, A.; Sharratt, N.; Montgomery, K.; Chambers, J. The psychosocial impact of alopecia in men: A mixed-methods survey study. Skin. Health Dis. 2024, 4, e420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahabreh, D.; Jung, S.; Renert-Yuval, Y.; Bar, J.; Del Duca, E.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Alopecia Areata: Current Treatments and New Directions. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2023, 24, 895–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezińska-Wcisło, L.; Bergler-Czop, B.; Wcisło-Dziadecka, D.; Lis-Święty, A. New aspects of the treatment of alopecia areata. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2014, 31, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J. Alopecia Areata: An Update on Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 61, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.C.; McCormick, J.; Pui, C.H.; Buddington, R.K.; Harvey, R.D. Preventing and Managing Toxicities of High-Dose Methotrexate. Oncologist 2016, 21, 1471–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlmann, V.; Moor, C.C.; Veltkamp, M.; Wijsenbeek, M.S. Patient reported side-effects of prednisone and methotrexate in a real-world sarcoidosis population. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2021, 18, 14799731211031935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, G.V.; Calmon, H.; Radel, G.; de Fátima Paim de Oliveira, M. Psoriasis and sexual dysfunction: Links, risks, and management challenges. Psoriasis 2018, 8, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodosiou, G.; Svensson, Å. Methotrexate-associated Sexual Dysfunction: Two Case Reports. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2017, 97, 1132–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakhem, G.A.; Goldberg, J.E.; Motosko, C.C.; Cohen, B.E.; Ho, R.S. Sexual dysfunction in men taking systemic dermatologic medication: A systematic review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowaczyk, J.; Makowska, K.; Rakowska, A.; Sikora, M.; Rudnicka, L. Cyclosporine With and Without Systemic Corticosteroids in Treatment of Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 10, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Ji, Z.G.; Tang, Y.W.; Zhang, L.; Lü, W.-C.; Lin, J.; Guo, H.-B.; Xie, Z.-L.; Sun, W.; DU, L.-D.; et al. Prevalence and influential factors of erectile dysfunction in male renal transplant recipients: A multiple center survey. Chin. Med. J. 2008, 121, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaroni, C.; Favia, G.; Lumachi, F.; Opocher, G.; Bonanni, G.; Mantero, F.; Armanini, D. Unilateral adrenal tumor, erectile dysfunction and infertility in a patient with 21-hydroxylase deficiency: Effects of glucocorticoid treatment and surgery. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2003, 111, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, L.N.; Masini, A.M.; Danna, M.M.; Kral, M.; Bruno, O.D.; A Rossi, M.; A Andrada, J. Glucocorticoids: Their role on gonadal function and LH secretion. Minerva Endocrinol. 1996, 21, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Renert-Yuval, Y.; Bares, J.; Chima, M.; Hawkes, J.E.; Gilleaudeau, P.; Sullivan-Whalen, M.; Singer, G.K.; Garcet, S.; Pavel, A.B.; et al. Phase 2a randomized clinical trial of dupilumab (anti-IL-4Rα) for alopecia areata patients. Allergy 2022, 77, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Kastl, S.; Battista, T.; Di Guida, A.; Martora, F.; Picone, V.; Ventura, V.; Patruno, C. Effect of Dupilumab on Sexual Desire in Adult Patients with Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis. Medicina 2022, 58, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, J.; Jimenez, J.J.; DelCanto, G.M.; Tosti, A. Treatment of Alopecia Areata with Simvastatin/Ezetimibe. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2018, 19, S25–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, D.; Kirby, M.; Wellsted, D.M.; Ali, S.; Hackett, G.; O’Connor, B.; van Os, S. Can simvastatin improve erectile function and health-related quality of life in men aged ≥40 years with erectile dysfunction? Results of the Erectile Dysfunction and Statins Trial [ISRCTN66772971]. BJU Int. 2013, 111, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuty-Pachecka, M. Cognitive-behavioural psychotherapy and alopecia areata. Psychiatr. Psychol. Klin. 2017, 17, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloh, J.; Engel, T.; Natarelli, N.; Nong, Y.; Zufall, A.; Sivamani, R.K. Systematic Review of Psychological Interventions for Quality of Life, Mental Health, and Hair Growth in Alopecia Areata and Scarring Alopecia. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heapy, C.; Norman, P.; Cockayne, S.; Thompson, A.R. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for social anxiety symptoms in people living with alopecia areata: A single-group case-series design. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2023, 51, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, A.; Bhugra, D. Sexuality in the 21st Century: Sexual Fluidity. East. Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2019, 29, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, T.S.; Nagaraj, A.K. Female sexuality. Indian. J. Psychiatry 2015, 57 (Suppl. S2), S296–S302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (Year) | Study Population (AA Patients) | Mean Age | SD Measurement Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. [63] (2018) | 81 (60) | 39.7 ± 13.8 years for women 37.4 ± 9.9 years for men | SQOL-F and SQOL-M |

|

| Barba et al. [64] (2024) | 120 (60) | * | Numerical scale and gender-specific questionnaires |

|

| Diaz et al. [65] (2022) | 120 (60) | AA patients: 39.68 ± 13.15 Controls: 40.21 ± 12.79 | IIEF-5 and FSFI-6 |

|

| Diaz et al. [67] (2022) | 84 (42) | AA patients: 40.59 ± 8.92 Cohabitants: 46.76 ± 12.10 | IIEF-5, FSFI-6, and numeric rating scale (NRS) for sexual impairment |

|

| Aldhouse et al. [69] (2020) | 45 (45) | 33.3 years | A semi-structured interview guide, developed with expert clinician input, including open-ended questions to explore patients’ experiences of living with AA |

|

| Kim et al. [71] (2020) | 38,530 (7706) | Unknown | Psychiatric disorder codes F01–F99 and all their subclassification codes |

|

| Zucchelli et al. [74] (2024) | 177 (94) | 47.05 | Cross-sectional online survey with closed and open-ended questions |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krajewski, P.K.; Złotowska, A.; Szepietowski, J.C.; Saceda Corralo, D. Sexual Dysfunction in Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082602

Krajewski PK, Złotowska A, Szepietowski JC, Saceda Corralo D. Sexual Dysfunction in Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(8):2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082602

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrajewski, Piotr K., Aleksandra Złotowska, Jacek C. Szepietowski, and David Saceda Corralo. 2025. "Sexual Dysfunction in Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 8: 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082602

APA StyleKrajewski, P. K., Złotowska, A., Szepietowski, J. C., & Saceda Corralo, D. (2025). Sexual Dysfunction in Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(8), 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082602