Impact of Integrated Psychiatric and Psychotherapeutic Treatment on Perceived Anxiety and Severity of Depressive Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Diagnosis of anxiety or depressive disorders, disease entity from F32, F33, and F40 to F48 according to the ICD 10 classification;

- Age range from 18 years old (patients before the age of 18 require a different specificity of therapeutic interventions that take into account the developmental process) up to the age of 60 (above 60 years of age, there are significant factors of a biological nature as well as those resulting from the stage of life that may interfere with the clinical picture of the study).

2.1.2. Criteria for Exclusion from Participation in the Study

- Addiction to psychoactive drugs, abstinence lasting less than a year, no participation in addiction therapy during abstinence;

- The presence of psychotic symptoms;

- Organic disorders (caused by brain dysfunction, disease, damage, or injury);

- Long history of psychotherapeutic treatment (more than 3 years) with no visible progress; no motivation to take psychotherapeutic treatment.

2.2. Specifics of Psychotherapeutic Interventions

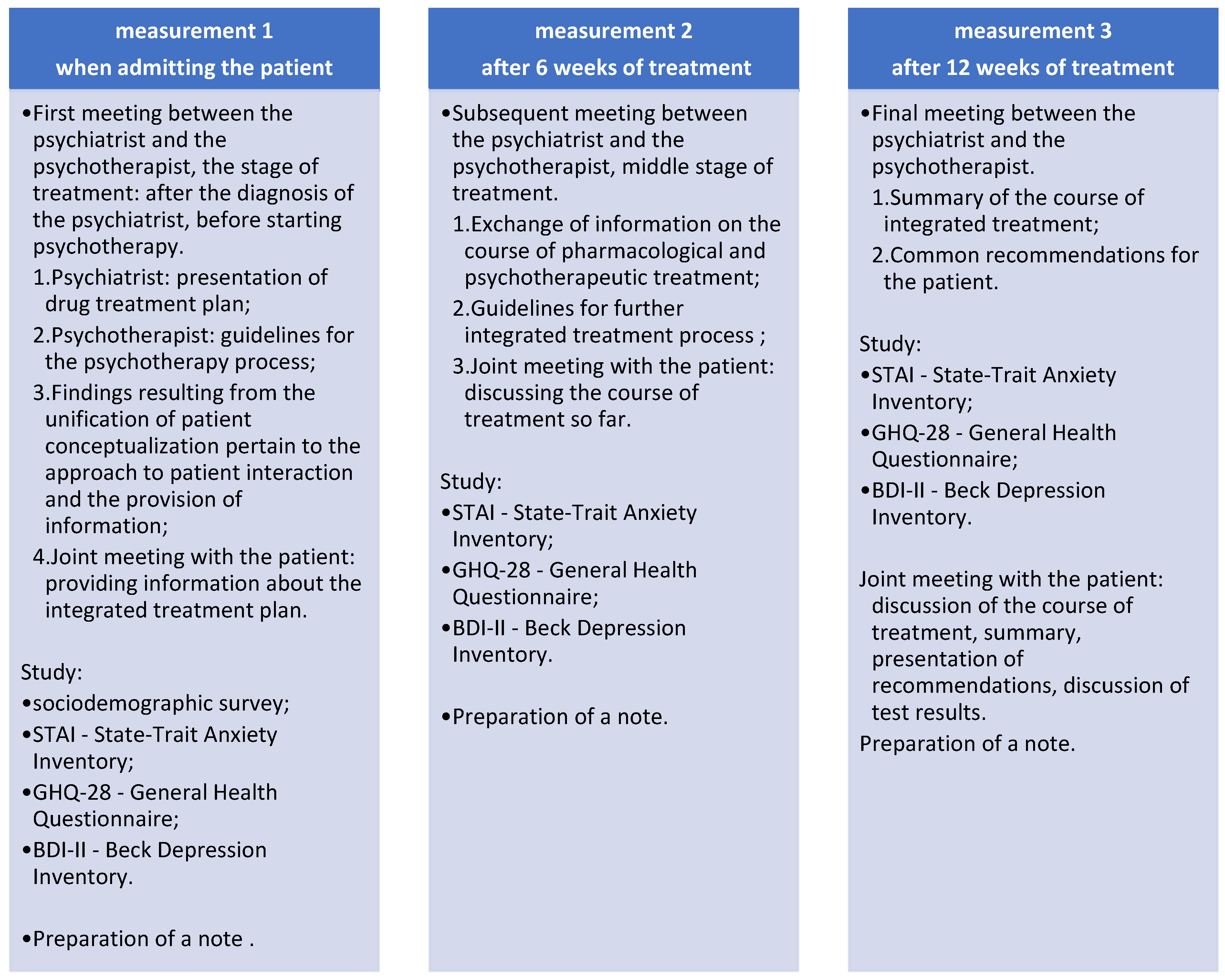

2.3. Study Protocol

2.4. Psychological Tool

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. Characteristics of the Control Group

3.3. Assessment of the Effect of Integrated Psychiatric and Psychotherapeutic Treatment on Anxiety Perception and the Severity of Depressive Symptoms

3.3.1. STATE ANXIETY (STAI)

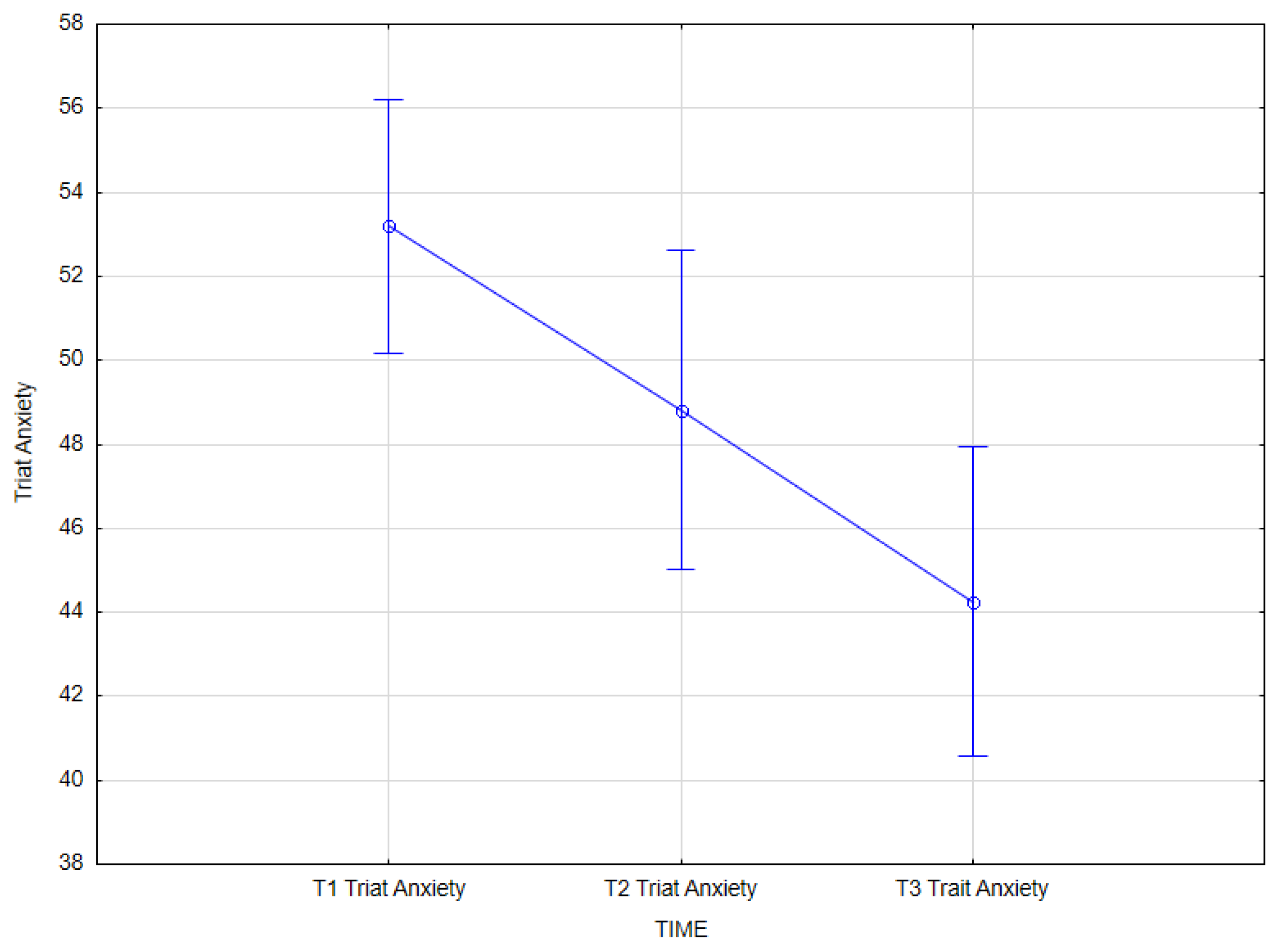

3.3.2. TRAIT ANXIETY (STAI)

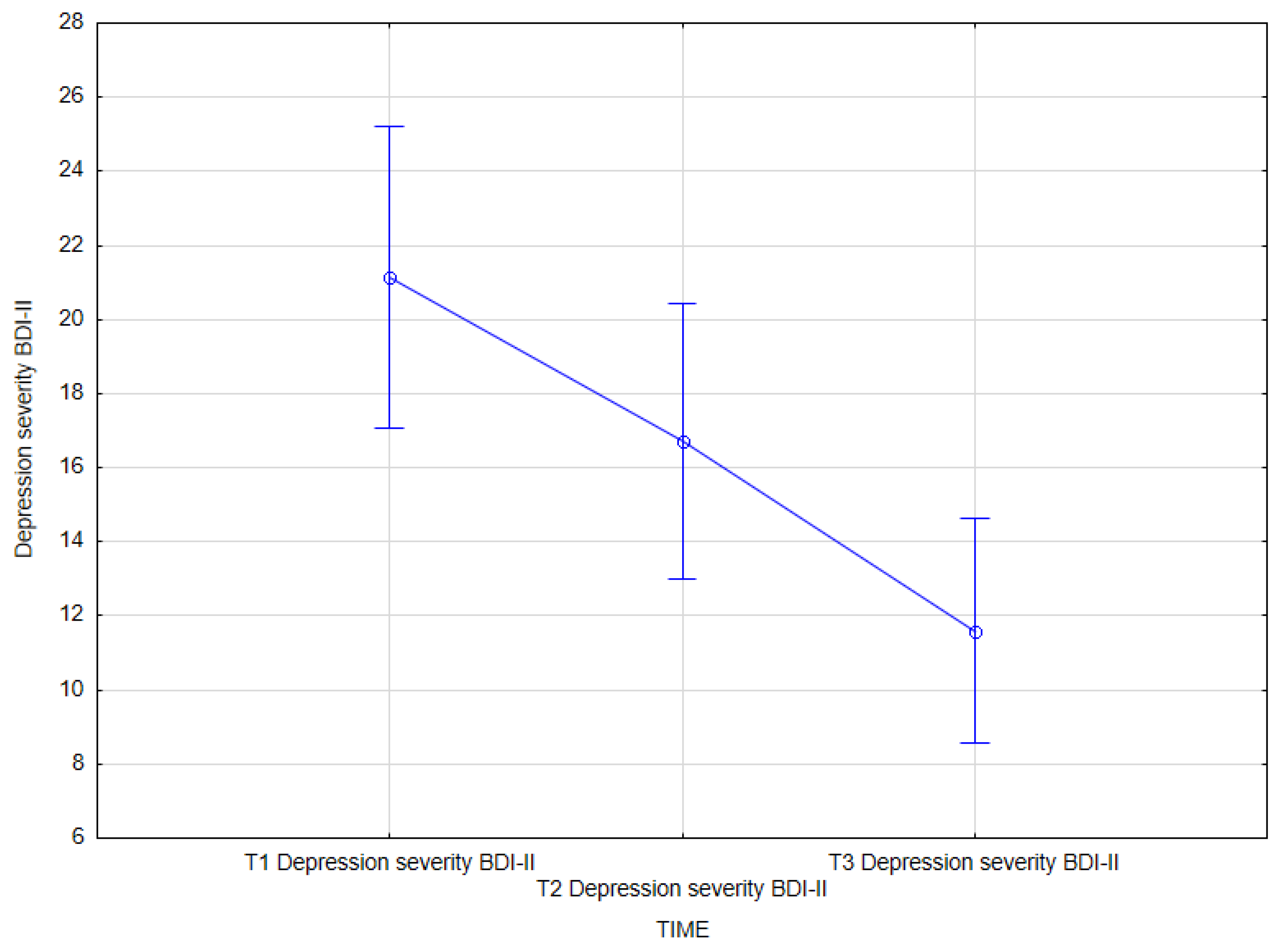

3.3.3. DEPRESSION SEVERITY (BDI-II)

3.3.4. SOMATIC SYMPTOMS (GHQ-28)

3.3.5. ANXIETY, INSOMNIA (GHQ-28)

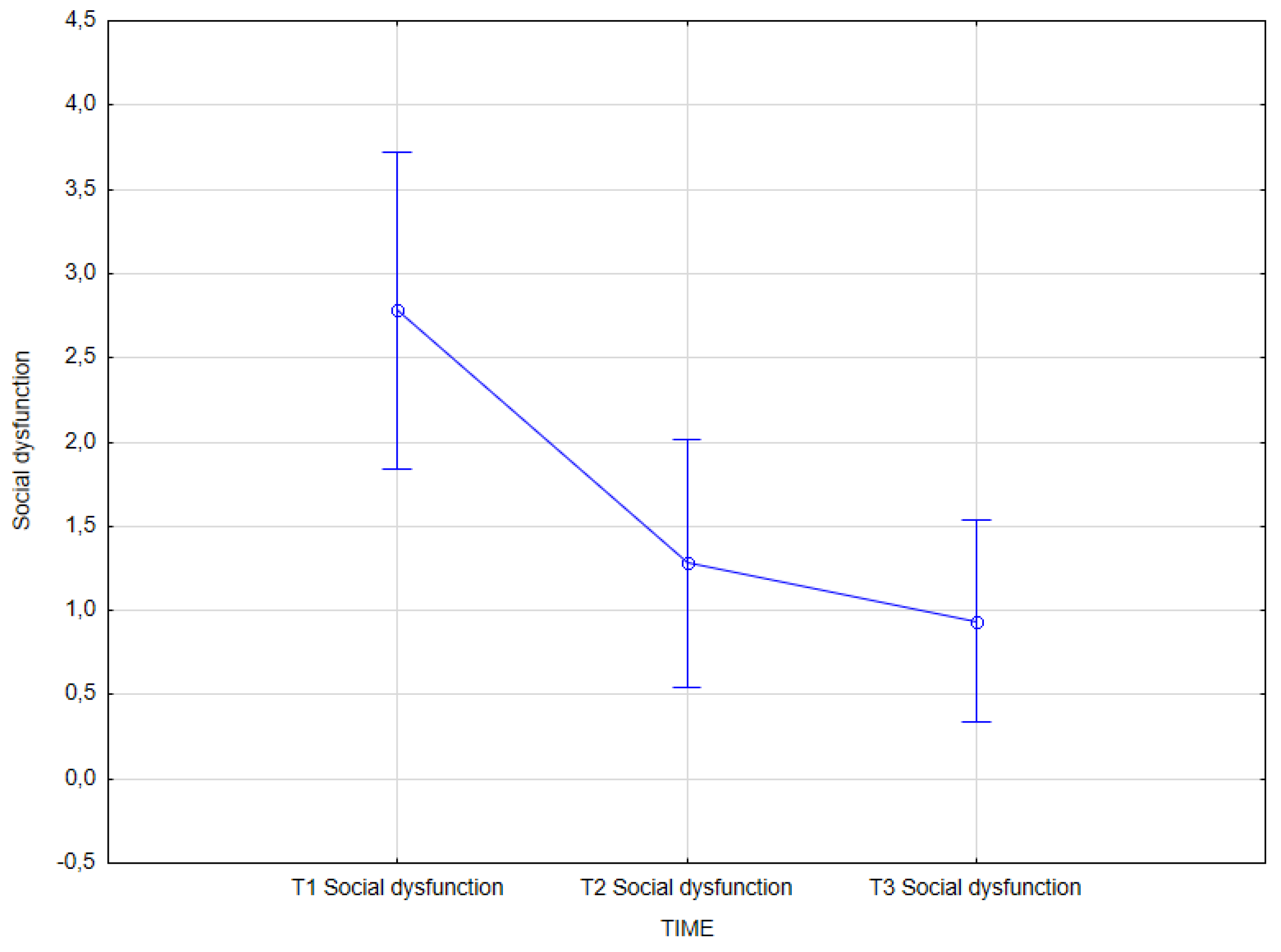

3.3.6. SOCIAL DYSFUNCTION (GHQ-28)

3.3.7. SEVERE DEPRESSION (GHQ-28)

3.3.8. MENTAL HEALTH ASSESSMENT (GHQ-28)

3.3.9. Comparison of the Effects of Integrated Approaches and Standard Psychotherapeutic Methods on the Clinical Symptoms Analyzed

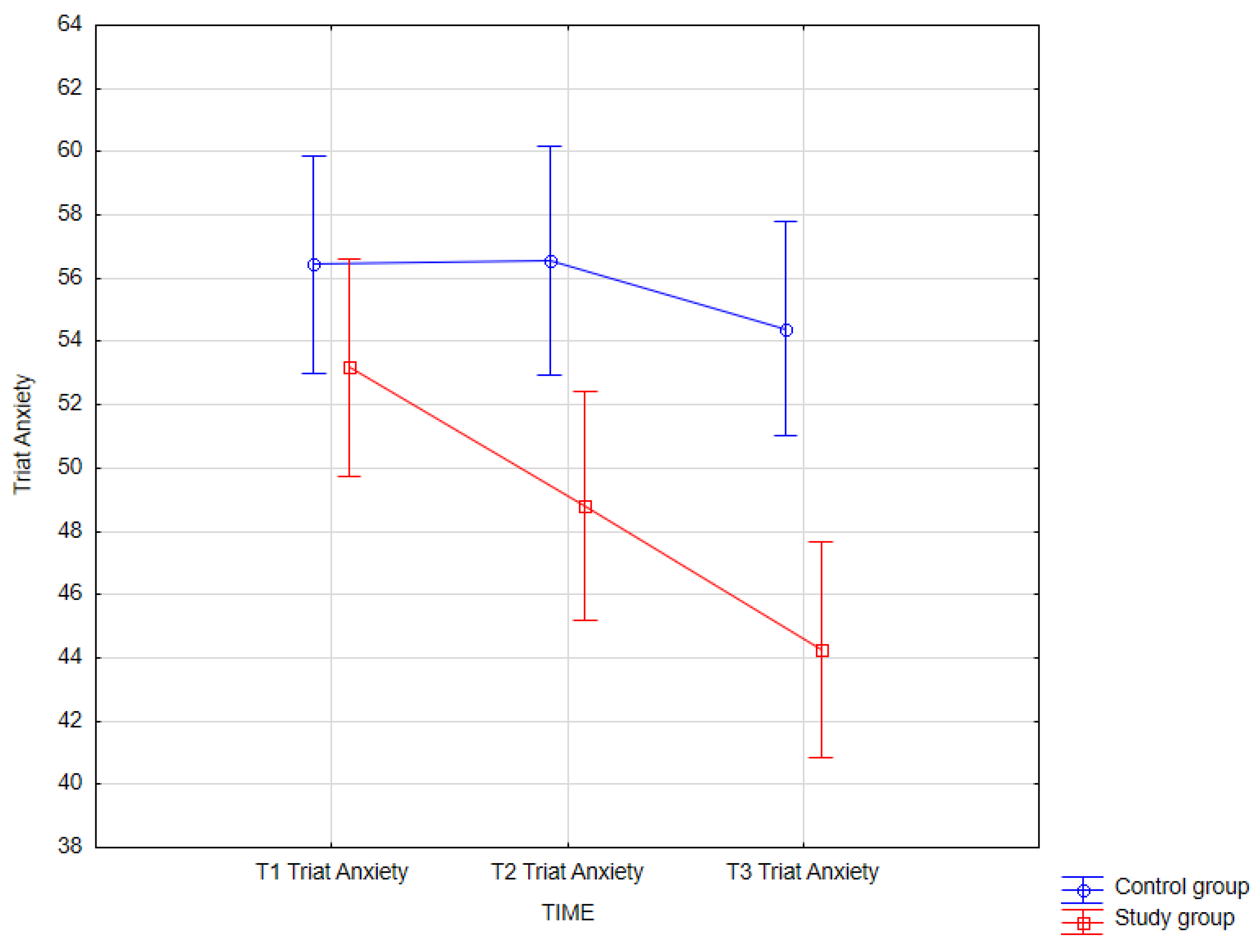

3.3.10. Trait Anxiety

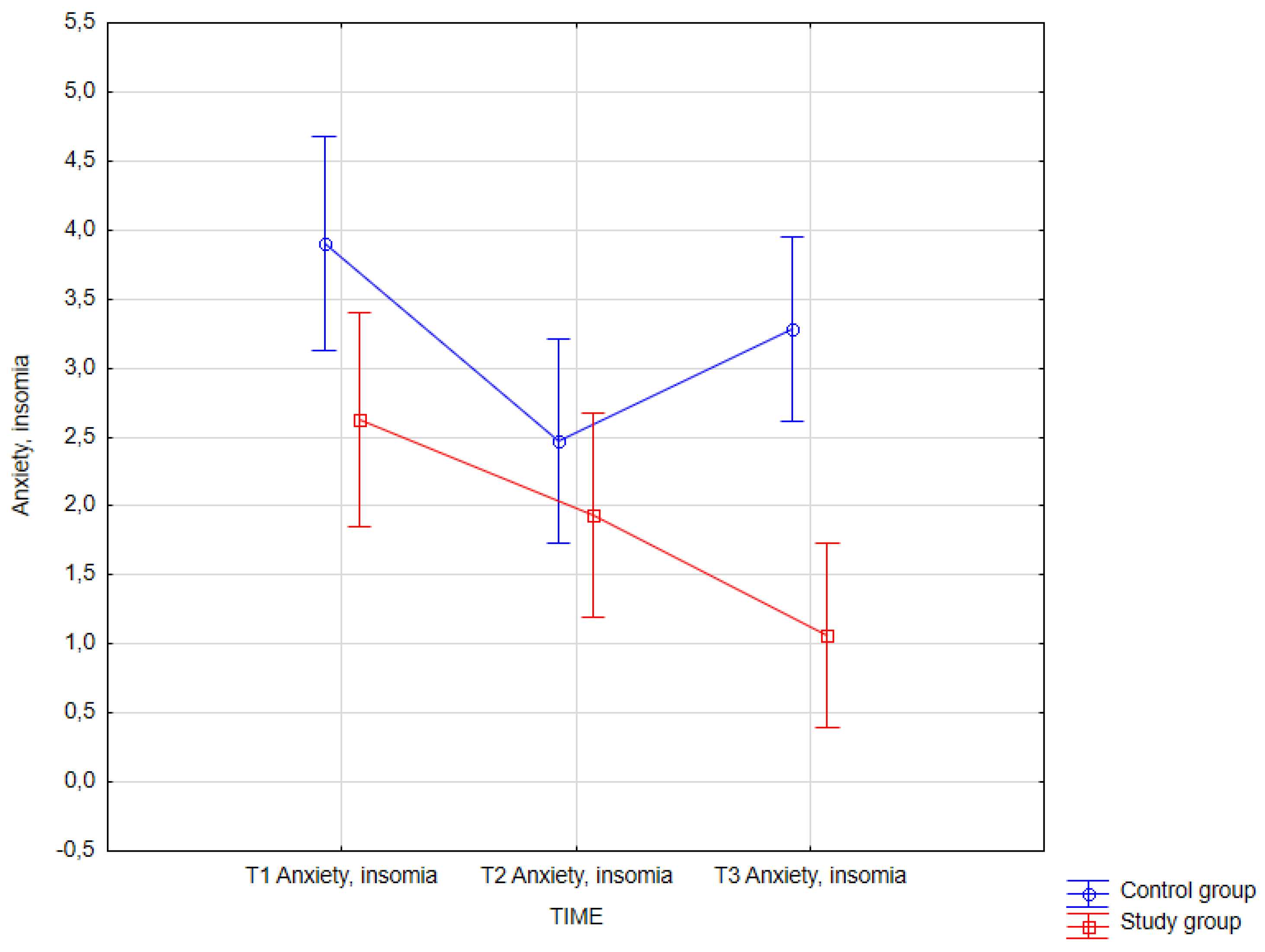

3.3.11. Anxiety, Insomnia (GHQ-28)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katz, R.; Ghosh, S.; Pomerantz, A. Integrated care in mental health: A systematic review. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 319–332. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P.; Karyotaki, E.; Ciharova, M.; Miguel, C.; Noma, H.; Furukawa, T.A. The effects of psychotherapies for depression on response, remission, reliable change, and deterioration: A meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021, 144, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meyer, B.; Sproten, A.; Schulte, M. Integrated care in mental health: Evidence and implications. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 59, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, M.; Kirtman, B.P.; Koster, R.D. Integrated care: A systematic review. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Asnaani, A.; Vonk, I.J.J.; Sawyer, A.T.; Fang, A. The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2012, 36, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H.R.; Miyake, A.; Hankin, B.L. Advancing understanding of executive function impairments and psychopathology: Bridging the gap between clinical and cognitive approaches. Front Psychol. 2015, 6, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopacz, M.S.; Lewis, J.T.; Hunsley, J. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for mood disorders in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2019, 48, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- ICD-10: World Health Organization. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42980 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Stanisz, A. Accessible Statistics Course Using STATISTICA PL on Examples from Medicine; Basic statistics; StatSoft Polska Sp. z o.o.: Kraków, Poland, 2006; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Brzeziński, J.M. Methodology of Psychological Research; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P.; Karyotaki, E.; Weitz, E.; Andersson, G.; Hollon, S.D.; van Straten, A. The effects of psychotherapies for major depression in adults on remission, recovery and improvement: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 159, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Steen, T.A.; Park, N.; Peterson, C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, A.; Echeburúa, E.; de la Rúa, M. Integrated care for mental health: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Integr. Care 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Julian, L.J. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. S11), S467–S472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Smith, J.; Brown, A.; Taylor, K. Efficacy of integrated psychiatric and psychological treatment for depression: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2021, 82, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.; Williams, R.; Carter, M. The impact of cognitive behavioral therapy on depression outcomes in combination with pharmacotherapy. Am. J. Psychiatry 2022, 179, 456–463. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, P.; Martinez, F.; Zhou, Y. Psychosocial interventions in depression: Enhancing outcomes through integrated care. Int. J. Ment. Health 2023, 52, 200–212. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, C.M.; LeBlanc, M.; Daley, M.; Gregoire, J.; Mérette, C. Epidemiology of insomnia: A systematic review of the literature. Sleep Med. Rev. 2006, 10, 409–418. [Google Scholar]

- van Straten, A.; Frijters, D.; Bergström, J.; Huibers, M.; Koole, G.; Andersson, G. The effects of psychotherapies for insomnia: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 38, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kobys, M.; Nowak, P.; Jankowski, T. The effectiveness of integrated care in mental health: A systematic review. J. Ment. Health Res. 2020, 45, 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Favaretto, E.; Bedani, F.; Brancati, G.E.; De Berardis, D.; Giovannini, S.; Scarcella, L.; Martiadis, V.; Martini, A.; Pampaloni, I.; Perugi, G.; et al. Synthesising 30 years of clinical experience and scientific insight on affective temperaments in psychiatric disorders: State of the art. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 362, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maina, G.; Adami, M.; Ascione, G.; Bondi, E.; De Berardis, D.; Delmonte, D.; Maffezzoli, S.; Martinotti, G.; Nivoli, A.; Ottavianelli, E.; et al. Nationwide consensus on the clinical management of treatment-resistant depression in Italy: A Delphi panel. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2023, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Education | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| b | 19 | 59.4 |

| c | 7 | 21.9 |

| a | 5 | 15.6 |

| d | 1 | 3.1 |

| Gender | Number | % | Basic Statistics for the Variable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chi2(df) | p Value | |||||||

| Female | 21 | 65.5 | 3.13 (1) | 0.077 | ||||

| Male | 11 | 34.4 | ||||||

| Marital status | Number | % | chi2(df) | p Value | ||||

| Single | 24 | 75.0 | 26.69 (2) | <0.001 | ||||

| Divorced | 1 | 3.1 | ||||||

| Married | 7 | 21.9 | ||||||

| Education | Number | % | chi2(df) | p Value | ||||

| Secondary | 19 | 59.4 | 22.50 (3) | <0.001 | ||||

| Vocational | 7 | 21.9 | ||||||

| Higher | 5 | 15.6 | ||||||

| Primary | 1 | 3.1 | ||||||

| Reason for seeking psychotherapy | Number | % | chi2(df) | p Value | ||||

| Increase in symptom severity | 15 | 46.9 | 23.00 (4) | <0.001 | ||||

| Referral from a psychiatrist | 10 | 31.3 | ||||||

| Inadequate previous pharmacological-only treatment | 5 | 15.6 | ||||||

| Family expectations | 1 | 3.1 | ||||||

| Interest in psychotherapy | 1 | 3.1 | ||||||

| Experience with psychotherapy | Number | % | chi2(df) | p Value | ||||

| Participation in psychotherapy for less than one year | 8 | 25.0 | 4.75 (3) | 0.191 | ||||

| Participation in only a few sessions so far | 6 | 18.8 | ||||||

| Participation in psychotherapy for more than one year | 13 | 40.6 | ||||||

| No experience | 5 | 15.6 | ||||||

| Medication use | Number | % | chi2(df) | p Value | ||||

| Yes | 31 | 96.9 | 28.13 (1) | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 1 | 3.1 | ||||||

| M | Min | Max | SD | As | K | W | p value | |

| Age | 32.38 | 19.00 | 57.00 | 11.51 | 0.77 | −0.66 | 0.89 | 0.003 |

| Duration of previous psychotherapy (months) | 16.09 | 0.00 | 84.00 | 19.91 | 1.80 | 3.48 | 0.78 | <0.001 |

| Duration of medication use (months) | 32.25 | 0.00 | 132.00 | 38.19 | 1.75 | 1.93 | 0.72 | <0.001 |

| Gender | Number | % | Basic Statistics for the Variable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chi2(df) | p Value | |||||||

| Female | 26 | 81.3 | 37.5 (1) | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 6 | 18.7 | ||||||

| Marital status | Number | % | chi2(df) | p Value | ||||

| Single | 25 | 78.6 | 49.50 (3) | <0.001 | ||||

| Divorced | 1 | 3.1 | ||||||

| Married | 5 | 15.6 | ||||||

| Widowed | 1 | 3.1 | ||||||

| Education | Number | % | chi2(df) | p Value | ||||

| Secondary | 17 | 53.1 | 16.75 (3) | 0.001 | ||||

| Vocational | 6 | 18.8 | ||||||

| Higher | 8 | 25.0 | ||||||

| Primary | 1 | 3.1 | ||||||

| Reason for seeking psychotherapy | Number | % | chi2(df) | p Value | ||||

| Increase in symptom severity | 13 | 40.6 | 15.25 (3) | 0.002 | ||||

| Referral from a psychiatrist | 14 | 43.8 | ||||||

| Inadequate previous pharmacological-only treatment | 3 | 9.4 | ||||||

| Family expectations | 2 | 6.3 | ||||||

| Experience with psychotherapy | Number | % | chi2(df) | p Value | ||||

| Participation in psychotherapy for less than one year | 6 | 18.8 | 45.75 (3) | 0.124 | ||||

| Participation in only a few sessions so far | 9 | 28.1 | ||||||

| Participation in psychotherapy for more than one year | 13 | 40.6 | ||||||

| No experience | 4 | 12.5 | ||||||

| Medication use | Number | % | chi2(df) | p Value | ||||

| Yes | 32 | 100.0 | - | - | ||||

| M | Min | Max | SD | As | K | W | p value | |

| Age | 30.50 | 19.00 | 58.00 | 11.21 | 0.79 | −0.54 | 0.87 | 0.001 |

| Duration of previous psychotherapy (months) | 8.63 | 0.00 | 36.00 | 8.59 | 1.33 | 1.98 | 0.86 | 0.001 |

| Duration of medication use (months) | 14.53 | 0.00 | 40.00 | 1.03 | 1.75 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.006 |

| Study Group | Control Group 0—Male | Control Group 1—Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0—male | 2 | 9 | 11 |

| 1—female | 4 | 17 | 21 |

| Total | 6 | 26 | 32 |

| Variable | M | Min | Max | SD | As | K | W | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, control group | 30.50 | 19.00 | 58.00 | 11.21 | 0.79 | −0.54 | 0.87 | 0.001 |

| Age, study group | 32.38 | 19.00 | 57.00 | 11.51 | 0.77 | −0.66 | 0.89 | 0.003 |

| Variable | M | Min | Max | SD | As | K | W | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State anxiety | 48.84 | 27.00 | 74.00 | 12.23 | 0.19 | −0.58 | 0.98 | 0.670 |

| Trait anxiety | 53.19 | 34.00 | 71.00 | 8.40 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.96 | 0.272 |

| Depression total, BDI-II | 21.16 | 0.00 | 56.00 | 11.31 | 0.69 | 1.62 | 0.96 | 0.314 |

| Somatic symptoms | 2.53 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 1.88 | 0.58 | −0.17 | 0.93 | 0.052 |

| Anxiety, insomnia | 2.63 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 2.38 | 0.45 | −1.14 | 0.89 | 0.003 |

| Social dysfunction | 2.78 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 2.60 | 0.41 | −1.33 | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| Severe depression | 2.19 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 2.40 | 0.84 | −0.54 | 0.83 | <0.001 |

| Mental health assessment total, GHQ-28 | 10.13 | 0.00 | 27.00 | 8.10 | 0.56 | −0.91 | 0.92 | 0.020 |

| Age | 32.38 | 19.00 | 57.00 | 11.51 | 0.77 | −0.66 | 0.89 | 0.003 |

| Variable | M | Min | Max | SD | As | K | W | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State anxiety | 45.44 | 27.00 | 66.00 | 10.56 | 0.13 | −0.66 | 0.96 | 0.340 |

| Trait anxiety | 48.81 | 29.00 | 77.00 | 10.53 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.97 | 0.559 |

| Depression total, BDI-II | 16.72 | 1.00 | 37.00 | 10.28 | 0.32 | −0.94 | 0.96 | 0.236 |

| Somatic symptoms | 2.22 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.77 | 0.35 | −1.09 | 0.90 | 0.007 |

| Anxiety, insomnia | 1.94 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 2.12 | 0.88 | −0.28 | 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Social dysfunction | 1.28 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 2.04 | 1.92 | 2.62 | 0.65 | <0.001 |

| Severe depression | 1.19 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 1.65 | 1.23 | 0.17 | 0.74 | <0.001 |

| Mental health assessment total, GHQ-28 | 6.63 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 6.07 | 0.89 | −0.47 | 0.87 | 0.001 |

| Variable | M | Min | Max | SD | As | K | W | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State anxiety | 41.44 | 27.00 | 67.00 | 10.66 | 0.81 | −0.10 | 0.93 | 0.030 |

| Trait anxiety | 44.25 | 28.00 | 72.00 | 10.20 | 0.77 | 0.28 | 0.95 | 0.104 |

| Depression total, BDI-II | 11.59 | 1.00 | 33.00 | 8.40 | 1.34 | 1.12 | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| Somatic symptoms | 1.72 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.76 | 1.06 | 0.48 | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety, insomnia | 1.06 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.39 | 1.04 | −0.27 | 0.76 | <0.001 |

| Social dysfunction | 0.94 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.66 | 2.03 | 3.77 | 0.63 | <0.001 |

| Severe depression | 0.53 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.27 | 3.10 | 10.97 | 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Mental health assessment total, GHQ-28 | 4.25 | 0.00 | 19.00 | 4.41 | 1.40 | 2.49 | 0.85 | 0.001 |

| Dependent Variable | T1 (n = 32) | T2 (n = 32) | T3 (n = 32) | F | df | P | η2partial | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||||

| State anxiety | 48.84 | 12.23 | 45.44 | 10.56 | 41.44 | 10.66 | 8.31 | 2, 62 | 0.001 | 0.211 |

| Trait anxiety | 53.19 | 8.40 | 48.81 | 10.53 | 44.25 | 10.20 | 17.73 | 2, 62 | <0.001 | 0.364 |

| Depression total, BDI-II | 21.16 | 11.31 | 16.72 | 10.28 | 11.59 | 8.40 | 17.00 | 2, 62 | <0.001 | 0.354 |

| Somatic symptoms | 2.53 | 1.88 | 2.22 | 1.77 | 1.72 | 1.76 | 2.14 | 2, 62 | 0.127 | 0.065 |

| Anxiety, insomnia | 2.63 | 2.38 | 1.94 | 2.12 | 1.06 | 1.39 | 8.73 | 2, 62 | <0.001 | 0.219 |

| Social dysfunction | 2.78 | 2.60 | 1.28 | 2.04 | 0.94 | 1.66 | 7.16 | 2, 62 | 0.002 | 0.187 |

| Severe depression | 2.19 | 2.40 | 1.19 | 1.65 | 0.53 | 1.27 | 10.09 | 2, 62 | 0.001 | 0.246 |

| Mental health assessment total, GHQ-28 | 10.13 | 8.10 | 6.63 | 6.07 | 4.25 | 4.41 | 10.24 | 2, 62 | 0.001 | 0.248 |

| Dependent Variable: State Anxiety | T1 (n = 32) | T2 (n = 32) | T3 (n = 32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 48.84 | 12.23 | 45.44 | 10.56 | 41.44 | 10.66 | |

| T1 | 0.197 | 0.001 | ||||

| T2 | 0.197 | 0.095 | ||||

| T3 | 0.001 | 0.095 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Trait Anxiety | T1 (n = 32) | T2 (n = 32) | T3 (n = 32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 53.19 | 8.40 | 48.81 | 10.53 | 44.25 | 10.20 | |

| T1 | 0.015 | <0.001 | ||||

| T2 | 0.015 | 0.010 | ||||

| T3 | <0.001 | 0.010 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Depression Severity (BDI-II) | T1 (n = 32) | T2 (n = 32) | T3 (n = 32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 21.16 | 11.31 | 16.72 | 10.28 | 11.59 | 8.40 | |

| T1 | 0.027 | <0.001 | ||||

| T2 | 0.027 | 0.008 | ||||

| T3 | <0.001 | 0.008 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Anxiety, Insomnia | T1 (n = 32) | T2 (n = 32) | T3 (n = 32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 2.63 | 2.38 | 1.94 | 2.12 | 1.06 | 1.39 | |

| T1 | 0.214 | <0.001 | ||||

| T2 | 0.214 | 0.069 | ||||

| T3 | <0.001 | 0.069 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Social Dysfunction | T1 (n = 32) | T2 (n = 32) | T3 (n = 32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 2.78 | 2.60 | 1.28 | 2.04 | 0.94 | 1.66 | |

| T1 | 0.016 | 0.002 | ||||

| T2 | 0.016 | 1.000 | ||||

| T3 | 0.002 | 1.000 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Severe Depression | T1 (n = 32) | T2 (n = 32) | T3 (n = 32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 2.19 | 2.40 | 1.19 | 1.65 | 0.53 | 1.27 | |

| T1 | 0.027 | <0.001 | ||||

| T2 | 0.027 | 0.246 | ||||

| T3 | <0.001 | 0.246 | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Mental Health Assessment (GHQ-28) | T1 (n = 32) | T2 (n = 32) | T3 (n = 32) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| 10.13 | 8.10 | 6.63 | 6.07 | 4.25 | 4.41 | |

| T1 | 0.027 | <0.001 | ||||

| T2 | 0.027 | 0.246 | ||||

| T3 | <0.001 | 0.246 | ||||

| Trait Anxiety—STAI X2 | F | p | η2partial | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 12.13 | <0.001 | 0.164 | 1 |

| Measurement time | 10.30 | <0.001 | 0.145 | 2 |

| Group × measurement time | 4.14 | 0.018 | 0.063 | 2 |

| Trait Anxiety (STAI X2) | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Subclass no. | gr | T | 56.44 | 10.91 | 56.56 | 9.93 | 54.41 | 8.97 | 53.19 | 8.40 | 48.81 | 10.53 | 44.25 | 10.20 |

| 1 | K | T1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.037 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 2 | K | T2 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.031 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 3 | K | T3 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.376 | 0.001 | |||||||

| 4 | B | T1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.185 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 5 | B | T2 | 0.037 | 0.031 | 0.376 | 0.185 | 0.137 | |||||||

| 6 | B | T3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.137 | |||||||

| Anxiety, Insomnia | F | p | η2partial | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| group | 11.61 | 0.001 | 0.158 | 1 |

| Measurement time | 9.28 | <0.001 | 0.130 | 2 |

| Group × measurement time | 4.28 | 0.016 | 0.065 | 2 |

| Anxiety, Insomnia | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Subclass no. | gr | T | 3.91 | 1.99 | 2.47 | 2.06 | 3.28 | 2.30 | 2.63 | 2.38 | 1.94 | 2.12 | 1.06 | 1.39 |

| 1 | K | T1 | 0.009 | 1.000 | 0.214 | 0.003 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 2 | K | T2 | 0.009 | 0.736 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.109 | |||||||

| 3 | K | T3 | 1.000 | 0.736 | 1.000 | 0.154 | <0.001 | |||||||

| 4 | B | T1 | 0.214 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.003 | |||||||

| 5 | B | T2 | 0.003 | 1.000 | 0.154 | 1.000 | 0.514 | |||||||

| 6 | B | T3 | <0.001 | 0.109 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.514 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maślankowski, J.; Wolska, A.; Bliźniewska-Kowalska, K.; Silczuk, A.; Gujski, M.; Szulc, A.; Kunikowska, J.; Gałecka, M. Impact of Integrated Psychiatric and Psychotherapeutic Treatment on Perceived Anxiety and Severity of Depressive Symptoms. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072175

Maślankowski J, Wolska A, Bliźniewska-Kowalska K, Silczuk A, Gujski M, Szulc A, Kunikowska J, Gałecka M. Impact of Integrated Psychiatric and Psychotherapeutic Treatment on Perceived Anxiety and Severity of Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(7):2175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072175

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaślankowski, Jacek, Aleksandra Wolska, Katarzyna Bliźniewska-Kowalska, Andrzej Silczuk, Mariusz Gujski, Agata Szulc, Justyna Kunikowska, and Małgorzata Gałecka. 2025. "Impact of Integrated Psychiatric and Psychotherapeutic Treatment on Perceived Anxiety and Severity of Depressive Symptoms" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 7: 2175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072175

APA StyleMaślankowski, J., Wolska, A., Bliźniewska-Kowalska, K., Silczuk, A., Gujski, M., Szulc, A., Kunikowska, J., & Gałecka, M. (2025). Impact of Integrated Psychiatric and Psychotherapeutic Treatment on Perceived Anxiety and Severity of Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(7), 2175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072175