Mission and One-Year Experience of a Kidney–Heart Outpatient Service: A Patient-Centered Management Model

Abstract

1. Cardiorenal Syndrome: A Multidisciplinary Challenge Requiring Integrated Care

2. Paradigm Shifts in Patient Management and Institutional Challenges

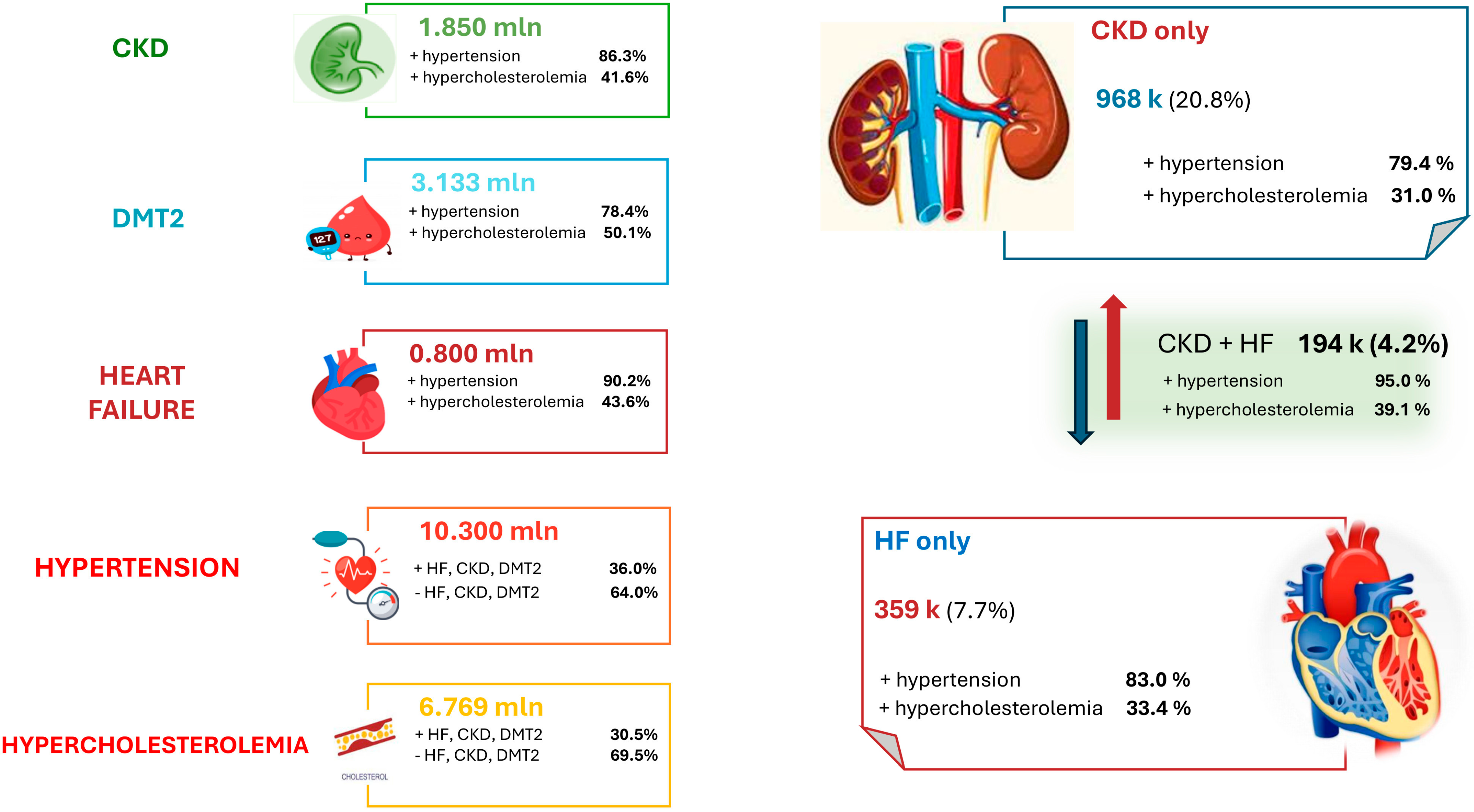

3. Epidemiological Insights in Cardiorenal Syndrome

4. Hospitalization Trends and Economic Burden

5. The Kidney–Heart Outpatient Service: Our Experience

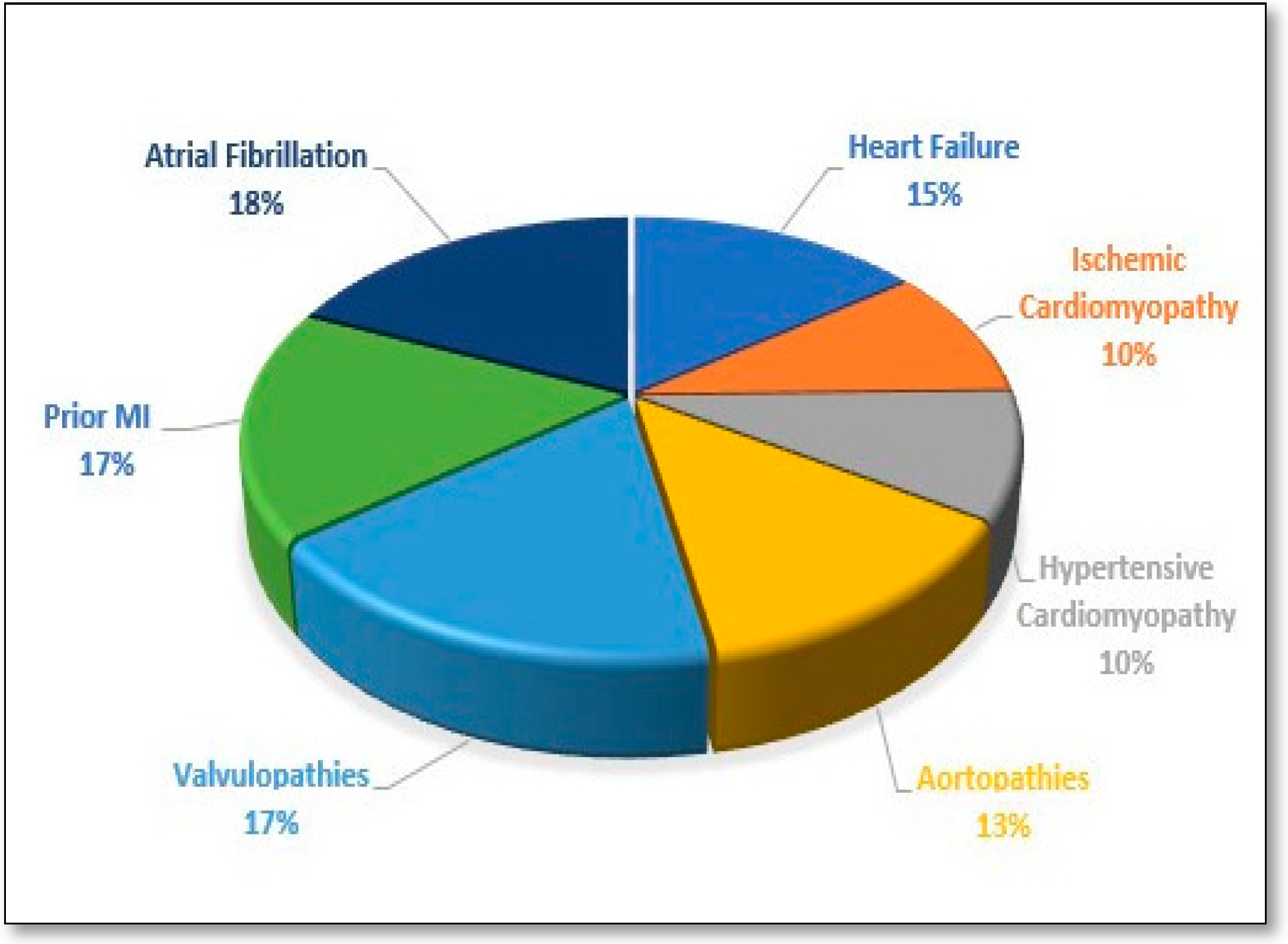

6. Preliminary Data

7. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Go, A.S.; Chertow, G.M.; Fan, D.; McCulloch, C.E.; Hsu, C.Y. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrier, R.W. Cardiorenal versus renocardiac syndrome: Is there a difference? Nat. Clin. Pract. Nephrol. 2007, 3, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, C.; McCullough, P.; Anker, S.D.; Anand, I.; Aspromonte, N.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Bellomo, R.; Berl, T.; Bobek, I.; Cruz, D.N.; et al. Cardio-renal syndromes: Report from the Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangaswami, J.; Bhalla, V.; Blair, J.E.A.; Chang, T.I.; Costa, S.; Lentine, K.L.; Lerma, E.V.; Mezue, K.; Molitch, M.; Mullens, W.; et al. Cardiorenal syndrome: Classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment strategies: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e840–e878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, A.A. Cardiorenal syndrome: Introduction. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 1798–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, B.; Ortiz, A.; Navarro-González, J.F.; Santamaría, R.; de Sequera, P.; Díez, J. From cardiorenal syndromes to cardionephrology: A reflection by nephrologists on renocardiac syndromes. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamizadeh, P. Introducing nephrocardiology. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 17, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, M.; Shah, A.D.; Singh, H.K.; Malieckal, D.A.; Rangaswami, J.; Jhaveri, K.D. Opportunities for subspecialization in nephrology. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020, 27, 320–327.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, R. History of medicine timeline. Heart Views 2015, 16, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, R.R. Reconciling evidence-based medicine and patient-centred care: Defining evidence-based inputs to patient-centred decisions. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 1076–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, D.M.; Pessanha, J.F.; Sharma, A.; Brocca, A.; Ronco, C. Delayed nephrology consultation and high mortality on acute kidney injury: A meta-analysis. Blood Purif. 2017, 43, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, D.W.; Stevens, G.R.; Wanchoo, R.; Majure, D.T.; Jauhar, S.; Fernandez, H.A.; Merzkani, M.; Jhaveri, K.D. Left ventricular assist devices and the kidney. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 13, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jentzer, J.C.; Bihorac, A.; Brusca, S.B.; Del Rio-Pertuz, G.; Kashani, K.; Kazory, A.; Kellum, J.A.; Mao, M.; Moriyama, B.; Morrow, D.A.; et al. Contemporary management of severe acute kidney injury and refractory cardiorenal syndrome: JACC Council perspectives. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1084–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansevoort, R.T.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Jafar, T.H.; Heerspink, H.J.; Mann, J.F.; Matsushita, K.; Wen, C.P. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet 2013, 382, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobo, O.; Abramov, D.; Davies, S.; Ahmed, S.B.; Sun, L.Y.; Mieres, J.H.; Parwani, P.; Siudak, Z.; Van Spall, H.G.C.; Mamas, M.A. CKD-Associated Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States: Temporal Trends From 1999 to 2020. Kidney Med. 2022, 5, 100597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ru, S.C.; Lv, S.B.; Li, Z.-J. Incidence, mortality, and predictors of acute kidney injury in patients with heart failure: A systematic review. ESC Heart Fail. 2023, 10, 3237–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.T. Development and Validation of a Prediction Model for Acute Kidney Injury Among Patients with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 719307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shetty, S.; Malik, A.H.; Ali, A.; Yang, Y.C.; Aronow, W.S.; Briasoulis, A. Impact of acute kidney injury on in-hospital outcomes among patients hospitalized with acute heart failure—A propensity-score matched analysis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 79, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottiroli, M.; Calini, A.; Morici, N.; Tavazzi, G.; Galimberti, L.; Facciorusso, C.; Ammirati, E.; Russo, C.; Montoli, A.; Mondino, M. Acute kidney injury in patients with acute decompensated heart failure-cardiogenic shock: Prevalence, risk factors and outcome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 383, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://osservatoriocrm.it/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Corrao, G.; Marrocco, W.; Del Prato, S.; Manfellotto, D.; Muiesan, M.L.; Norata, D. Valutazione Della Fragilità ed Approccio al Paziente Fragile. 2023. Available online: https://www.siprec.it/pubblicazioni/articoli-scientifici/siprec-partner/valutazione-della-fragilita-ed-approccio-al-paziente-fragile.html (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Aparicio, H.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Cheng, S.; Delling, F.N.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics- 2021 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e254–e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloatti, S.; Strippoli, G.F.; Buccianti, G.; Daidone, G.; Schena, F.P.; Italian Society of Nephrology. Current structure and organization for renal patient assistance in Italy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damman, K.; Valente, M.A.; Voors, A.A.; O’Connor, C.M.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Hillege, H.L. Renal impairment, worsening renal function, and outcome in patients with heart failure: An updated meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, A.; Navarro-González, J.; Núñez, J.; de la Espriella, R.; Cobo, M.; Santamaría, R.; de Sequera, P.; Díez, J. The unmet need of evidence-based therapy for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease and heart failure: Position paper from the Cardiorenal Working Groups of the Spanish Society of Nephrology and the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Clin. Kidney J. 2021, 15, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donati, C.; Addonisio, G.; Coletta, V.; Lena, S.; Cassoni, A.; Basiglini, A. Ospedali & Salute, 21° Rapporto Annuale Censis/Aiop; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2024; ISBN -13 (15) 9788835164609. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, N.; Federici, M.; Schütt, K.; Müller-Wieland, D.; Ajjan, R.A.; Antunes, M.J.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Crawford, C.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Eliasson, B.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes: Developed by the task force on the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 4043–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carollo, C.; Evola, S.; Sorce, A.; Cirafici, E.; Bennici, M.; Mulè, G.; Geraci, G. Mission and One-Year Experience of a Kidney–Heart Outpatient Service: A Patient-Centered Management Model. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062102

Carollo C, Evola S, Sorce A, Cirafici E, Bennici M, Mulè G, Geraci G. Mission and One-Year Experience of a Kidney–Heart Outpatient Service: A Patient-Centered Management Model. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(6):2102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062102

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarollo, Caterina, Salvatore Evola, Alessandra Sorce, Emanuele Cirafici, Miriam Bennici, Giuseppe Mulè, and Giulio Geraci. 2025. "Mission and One-Year Experience of a Kidney–Heart Outpatient Service: A Patient-Centered Management Model" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 6: 2102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062102

APA StyleCarollo, C., Evola, S., Sorce, A., Cirafici, E., Bennici, M., Mulè, G., & Geraci, G. (2025). Mission and One-Year Experience of a Kidney–Heart Outpatient Service: A Patient-Centered Management Model. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(6), 2102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062102