Preliminary Results of a Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial for Laparoscopic Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Sacropexy vs. Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension

Abstract

1. Introduction

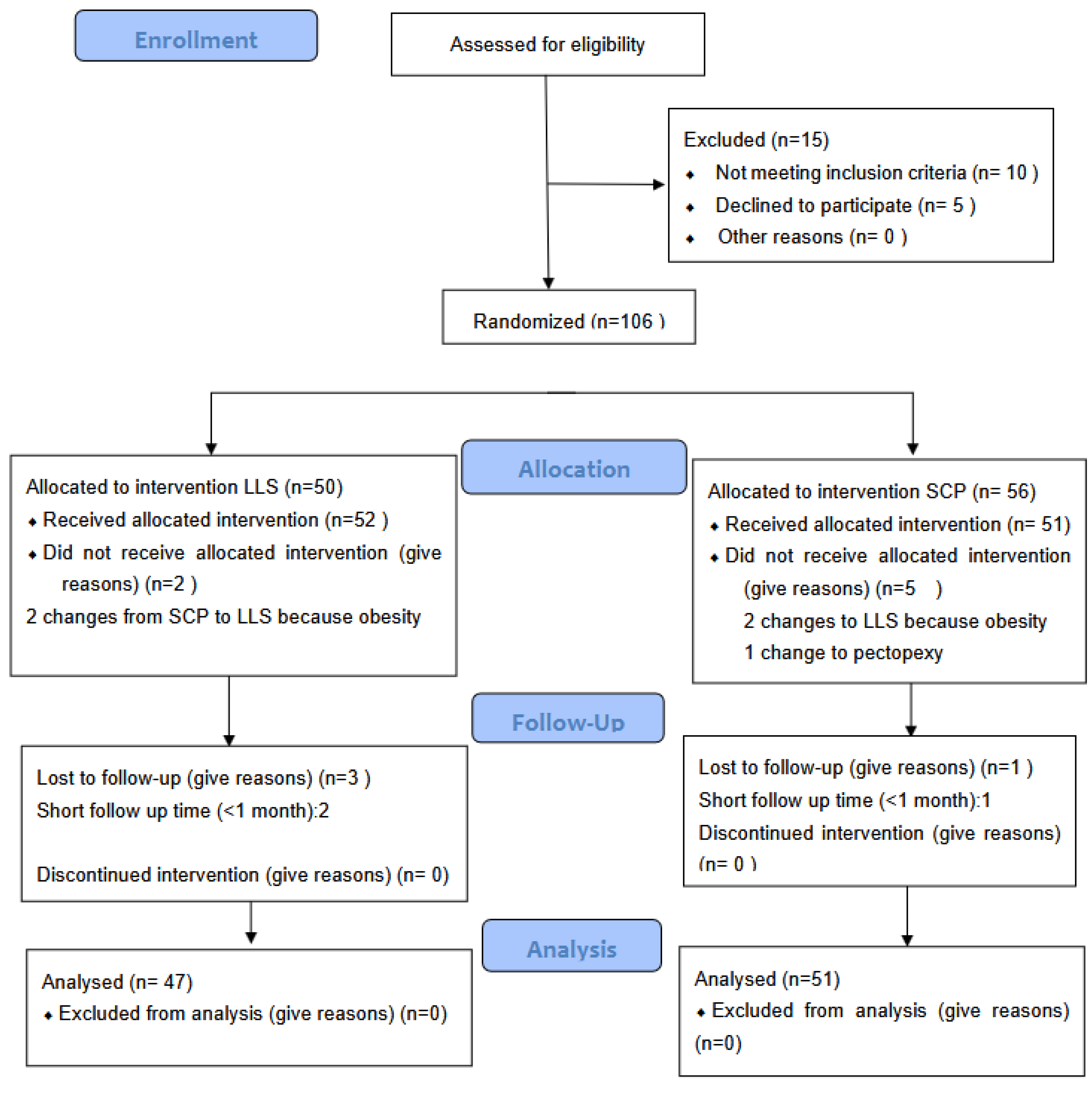

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Group A: lateral laparoscopic suspension (LLS).

- -

- Group B: Sacropexy (SCL) without posterior mesh fixation on the puborectalis muscle.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| POP | pelvic organ prolapse |

| SCL | sacropexy (laparoscopic) |

| LLS | laparoscopic lateral suspension |

| POPQ | pelvic organ prolapse quantification |

| PFDI-20 | Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory Questionnaire-Short Form 20 |

| POPDI-6 | Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory |

| CRAD-8 | Colorectal–Anal Distress Inventory |

| UDI-6 | Urinary Distress Inventory |

| PISQ-12 | Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Function Questionnaire |

| BMI | body mass index |

References

- Wu, J.M.; Hundley, A.F.; Fulton, R.G.B.; Myers, E.R. Forecasting the Prevalence of Pelvic Floor Disorders in U.S. Women 2010 to 2050. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 1278–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, C.; Feiner, B.; Baessler, K.; Christmann-Schmid, C.; Haya, N.; Brown, J. Surgery for women with anterior compartment prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2017, CD004014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, F.J.; Holman, A.J.; Moorin, R.E.; Tsokos, N. Lifetime Risk of Undergoing Surgery for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 116, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedel, A.; Tegerstedt, G.; Maehle-Schmidt, M.; Nyrén, O.; Hammarström, M. Nonobstetric Risk Factors for Symptomatic Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 113, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luber, K.M.; Boero, S.; Choe, J.Y. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: Current observations and future projections. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 184, 1496–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunda, A.; Vashisht, A.; Cutner, A. New procedures for uterine prolapse. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013, 27, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, S.S.; Jones, K.A.; Wang, L.; Bunker, C.H.; Lowder, J.L.M. Trends over time with commonly performed obstetric and gynecologic inpatient procedures. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 116, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolen, A.-L.W.M.; Bui, B.N.; Dietz, V.; Wang, R.; van Montfoort, A.P.A.; Mol, B.W.J.; Roovers, J.-P.W.R.; Bongers, M.Y. The treatment of post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 1767–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.Y.M.; Grimes, C.L.; Casiano, E.R.; Abed, H.T.; Jeppson, P.C.; Olivera, C.K.; Sanses, T.V.; Steinberg, A.C.D.; South, M.M.; Balk, E.M.; et al. Mesh sacrocolpopexy compared with native tissue vaginal repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 125, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattiez, A.; Canis, M.; Mage, G.; Pouly, J.; Bruhat, M. Promontofixation for the treatment of prolapse. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 28, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akladios, C.Y.; Dautun, D.; Saussine, C.; Baldauf, J.J.; Mathelin, C.; Wattiez, A. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for female genital organ prolapse: Establishment of a learning curve. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2010, 149, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, K.C.; Latchamsetty, K.; Govier, F.E.; Kozlowski, P.; Kobashi, K.C. Comparison of laparoscopic and abdominal sacrocolpopexy for the treatment of vaginal vault prolapse. J. Endourol. 2007, 21, 926–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claerhout, F.; De Ridder, D.; Roovers, J.P.; Rommens, H.; Spelzini, F.; Vandenbroucke, V.; Coremans, G.; Deprest, J. Medium-Term Anatomic and Functional Results of Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy Beyond the Learning Curve. Eur. Urol. 2008, 55, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noé, K.-G.; Schiermeier, S.; Alkatout, I.; Anapolski, M. Laparoscopic pectopexy: A prospective, randomized, comparative clinical trial of standard laparoscopic sacral colpocervicopexy with the new laparoscopic pectopexy-Postoperative results and intermediate-term follow-up in a pilot study. J. Endourol. 2015, 29, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuisson, J.-B.; Yaron, M.; Wenger, J.-M.; Jacob, S. Treatment of Genital Prolapse by Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension Using Mesh: A Series of 73 Patients. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2008, 15, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veit-Rubin, N.; Dubuisson, J.-B.; Gayet-Ageron, A.; Lange, S.; Eperon, I. Patient satisfaction after laparoscopic lateral suspension with mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: Outcome report of a continuous series of 417 patients. Int. Urogynecology J. 2017, 28, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eperon, I.; Dällenbach, P.; Dubuisson, J.-B. Laparoscopic repair of vaginal vault prolapse by lateral suspension with mesh. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 287, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veit-Rubin, N.; de Jolinière, J.B.; Dubuisson, J.-B. Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension: Benefits of a Cross-shaped Mesh to Treat Difficult Vaginal Vault Prolapse. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2016, 23, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoncini, T.; Panattoni, A.; Cadenbach-Blome, T.; Caiazzo, N.; García, M.C.; Caretto, M.; Chun, F.; Francescangeli, E.; Gaia, G.; Giannini, A.; et al. Role of lateral suspension for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: A Delphi survey of expert panel. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 4344–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.; Guevara, M.M.M.; Sacinti, K.G.; Misasi, G.; Falcone, M.; Morganti, R.; Mereu, L.; Dalprà, F.; Tateo, S.; Simoncini, T. Minimal Invasive Abdominal Sacral Colpopexy and Abdominal Lateral Suspension: A Prospective, Open-Label, Multicenter, Non-Inferiority Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, G.; Vacca, L.; Panico, G.; Caramazza, D.; Lombisani, A.; Scambia, G.; Ercoli, A. Laparoscopic lateral suspension for pelvic organ prolapse: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 264, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bump, R.C.; Mattiasson, A.; Bø, K.; Brubaker, L.P.; DeLancey, J.O.; Klarskov, P.; Shull, B.L.; Smith, A.R. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 175, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber; Walters; Bump, R. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 193, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.G.; Coates, K.W.; Kammerer-Doak, D.; Khalsa, S.; Qualls, C. A short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2003, 14, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelovsek, J.E.; Barber, M.D. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1455–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, O.; Yassa, M.; Eren, E.; İlter, P.B.; Tuğ, N. A randomized, prospective, controlled study comparing uterine preserving laparoscopic lateral suspension with mesh versus laparoscopic sacrohysteropexy in the treatment of uterine prolapse. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 297, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malanowska-Jarema, E.; Starczewski, A.; Melnyk, M.; Oliveira, D.; Balzarro, M.; Rubillota, E. A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Dubuisson Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension with Laparoscopic Sacropexy for Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Short-Term Results. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technique | LLS | Sacropexy | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | Median (p25–p75) | n | Mean | Median (p25–p75) | ||

| Age | 50 | 57.9 ± 9.5 | 59.0 (50.0–67.0) | 56 | 54.7 ± 10.3 | 53.0 (47.0–61.8) | 0.047 |

| BMI | 49 | 26.2 ± 4.8 | 25.2 (22.7–28.3) | 56 | 27.0 ± 3.9 | 26.5 (24.5–29.8) | 0.122 |

| n° Pregnancy | 50 | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 56 | 2.7 ± 1.4 | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 0.886 |

| n° Vaginal delivery | 50 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 56 | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 2.0 (1.3–3.0) | 0.567 |

| Stage of POP Q ≥ II n (%) | |||||||

| II | 1 (2.6%) | 2.0 (4.7%) | 0.615 | ||||

| III-IV | 38.0 (97.4%) | 31.0 (95.3%) | |||||

| Questionnaire PFDI-20 | |||||||

| POPDI-6 (0–24) | 40 | 12.4 ± 5.8 | 12.5 (7.3–16.0) | 37 | 14.5 ± 6.2) | 14.0 (11.0–19.5) | 0.137 |

| CRADI-8 (0–32) | 41 | 12.0 ± 24.8 | 8.0 (4.5–10.5) | 36 | 8.1 ± 4.7) | 8.0 (4.3–11.8) | 0.616 |

| UDI-6 (0–24) | 41 | 13.1 ± 6.3 | 13.0 (9.0–18.0) | 36 | 12.7 ± 6.0) | 13.0 (9.0–17.8) | 0.761 |

| PISQ-12 (0–48) | 38 | 28.7 ± 9.0 | 29.0 (22.8–36.0) | 33 | 29.2 ± 9.3) | 28.0 (23.5–36.5) | 0.917 |

| Body image scale n (%) | |||||||

| normal | 9 (30.0%) | 4.0 (28.6%) | |||||

| abnormal | 21.0 (70%) | 10.0 (71.4%) | 0.923 | ||||

| POP-Q points | |||||||

| Aa | 48 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 51 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 2.0 (1.5–3.0) | 0.020 |

| Ba | 48 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 1.5 (1.0–2.0) | 51 | 2.5 ± 2.3 | 3.0 (1.0–4.0) | 0.006 |

| C o D | 48 | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 2.0 (0.0–2.4) | 51 | 2.8 ± 2.4 | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 0.017 |

| Ap | 47 | −1.1 ± 1.4 | −1.0 (−2.0–0.0) | 50 | −0.7 ± 2.0 | −1.0 (−2.0–1.0) | 0.528 |

| Bp | 44 | −1.3 ± 1.7 | −2.0 (−3.0–0.0) | 50 | −0.5 ± 3.0 | −1.0 (−2.1–0.0) | 0.172 |

| gh | 47 | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 4.5 (4.0–5.0) | 50 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 0.060 |

| pb | 45 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 3.0 (2.0–3.5) | 50 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.0 (2.0–3.5) | 0.469 |

| tvl | 47 | 7.4 ± 1.0 | 7.0 (7.0–8.0) | 49 | 7.8 ± 1.3 | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) | 0.131 |

| Technique | LLS | Sacropexy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Median (p25–p75) | N | Mean | Median (p25–p75) | p-Value | 95% CI Mean Differences | |

| Operative time (min) | 47 | 76.1 ± 58.6 | 85.0 (0.1–110.0) | 51 | 164.7 + 84.9 | 180.0 (140.0–210.0) | <0.001 | −88.6 [−118.1, −59.1] |

| Other surgery times (min) | 23 | 8.0 ± 11.7 | 0.0 (0.0–15.0) | 10 | 5.5 + 11.2 | 0.0 (0.0–10.0) | 0.466 | 2.5 [−6.4, 11.5] |

| Surgery complications | 45 | 1.1 ± 7.2 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 49 | 1.1 + 7.9 | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.964 | −0.1 [−3.1, 3.0] |

| Hemoglobin 24 h after surgery | 44 | 11.7 ± 3.9 | 11.9 (8.6–12.5) | 49 | 11.5 + 2.5 | 11.5 (10.1–12.6) | 0.969 | −4526.8 [−9282.3, 228.7] |

| VAS: pain 1° day after surgery (0–10) | 22 | 3.5 ± 2.1 | 4.0 (1.8–5.0) | 20 | 3.6 ± 2.2 | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 0.929 | −0.1 [−1.5, 1.2] |

| Questionnaire PFDI-20: | ||||||||

| POPDI-6 (0–24) | 33 | 5.5 ± 4.9 | 6.0 (1.0–8.0) | 41 | 5.1 ± 5.5 | 4.0 (0.5–8.0) | 0.594 | 0.4 [−2.1, 2.8] |

| CRADI-8 (0–32) | 33 | 4.7 ± 4.9 | 3.0 (1.5–6.0) | 41 | 6.4 ± 5.8 | 4.0 (2.0–10.5) | 0.274 | −1.7 [−4.2, 0.8] |

| UDI-6 (0–24) | 33 | 5.9 ± 4.5 | 6.0 (1.5–10.0) | 41 | 7.5 ± 6.1 | 6.0 (2.5–11.0) | 0.407 | −1.6 [−4.2, 0.9] |

| PISQ-12 (0–48) | 20 | 20.7 ± 11.7 | 17.0 (13.0–30.8) | 31 | 27.0 ± 11.0 | 27.0 (18.0–38.0) | 0.056 | −6.4 [−12.9, 0.2] |

| Body image scale n (%) | ||||||||

| normal | 12 (93.3%) | 9 (81.8%) | 0.576 | 10.49% [−16.52%, 37.50%] | ||||

| abnormal | 1 (7.7%) | 2 (18.2%) | ||||||

| POP-Q points | ||||||||

| Aa | 35 | −2.2 + 1.3 | −2.0(−3.0–1.5) | 42 | −2.3 + 1.1 | −3.0(−3.0–2.0) | 0.377 | −0.1 [−0.4, 0.2] |

| Ba | 35 | −2.8 ± 1.4 | −3.0 (−3.0–2.0) | 42 | −2.3 ± 1.1 | −3.0 (−3.0–2.0) | 0.077 | 0.2 [−0.4, 0.7] |

| C o D | 35 | −4.0 ± 3.5 | −5.0 (−6.0–1.0) | 42 | −5.0 ± 2.6 | −6.0 (−7.0–4.4) | 0.161 | −0.6 [−1.1, 0.0] |

| Ap | 34 | −1.8 ± 1.3 | −2.0 (−3.0–1.0) | 41 | −2.1 ± 1.2 | −3.0 (−3.0–1.5) | 0.191 | 1.0 [−0.4, 2.4] |

| Bp | 34 | −2.7 ± 1.2 | −3.0 (−3.0–2.0) | 41 | −2.1 ± 1.3 | −3.0 (−3.0–1.3) | 0.189 | 0.3 [−0.3, 0.9] |

| gh | 35 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 41 | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 4.0 (3.5–5.0) | 0.452 | −0.5 [−1.1, 0.0] |

| pb | 34 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 3.0 (2.0–3.5) | 41 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 3.0 (2.0–3.3) | 0.539 | 0.2 [−0.3, 0.7] |

| tvl | 35 | 7.6 ± 1.0 | 8.0 (7.0–8.0) | 41 | 8.1 ± 1.2 | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) | 0.066 | −0.5 [−1.0, 0.0] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ñíguez-Sevilla, I.; Sánchez-Ferrer, M.L.; Ruiz-Cotorruelo, V.L.; Wilczak, M.; Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Solano-Calvo, J.A.; Pérez-Muñuzuri, M.E.; Salinas-Peña, J.R.; Arense-Gonzalo, J.J. Preliminary Results of a Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial for Laparoscopic Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Sacropexy vs. Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062069

Ñíguez-Sevilla I, Sánchez-Ferrer ML, Ruiz-Cotorruelo VL, Wilczak M, Chmaj-Wierzchowska K, Solano-Calvo JA, Pérez-Muñuzuri ME, Salinas-Peña JR, Arense-Gonzalo JJ. Preliminary Results of a Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial for Laparoscopic Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Sacropexy vs. Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(6):2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062069

Chicago/Turabian StyleÑíguez-Sevilla, Isabel, María Luisa Sánchez-Ferrer, Vicente Luis Ruiz-Cotorruelo, Maciej Wilczak, Karolina Chmaj-Wierzchowska, Juan Antonio Solano-Calvo, María Elena Pérez-Muñuzuri, Juan Raúl Salinas-Peña, and Julián Jesús Arense-Gonzalo. 2025. "Preliminary Results of a Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial for Laparoscopic Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Sacropexy vs. Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 6: 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062069

APA StyleÑíguez-Sevilla, I., Sánchez-Ferrer, M. L., Ruiz-Cotorruelo, V. L., Wilczak, M., Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K., Solano-Calvo, J. A., Pérez-Muñuzuri, M. E., Salinas-Peña, J. R., & Arense-Gonzalo, J. J. (2025). Preliminary Results of a Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial for Laparoscopic Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Sacropexy vs. Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(6), 2069. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062069