The CarerQol Instrument: A Systematic Review, Validity Analysis, and Generalization Reliability Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Reality of Informal Care

1.2. Other Instruments Measuring Caregiver Burden

1.3. The Care-Related Quality of Life Instrument (CarerQol)

1.4. Objetives and Relevance of Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Registration of Review

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Itinerary

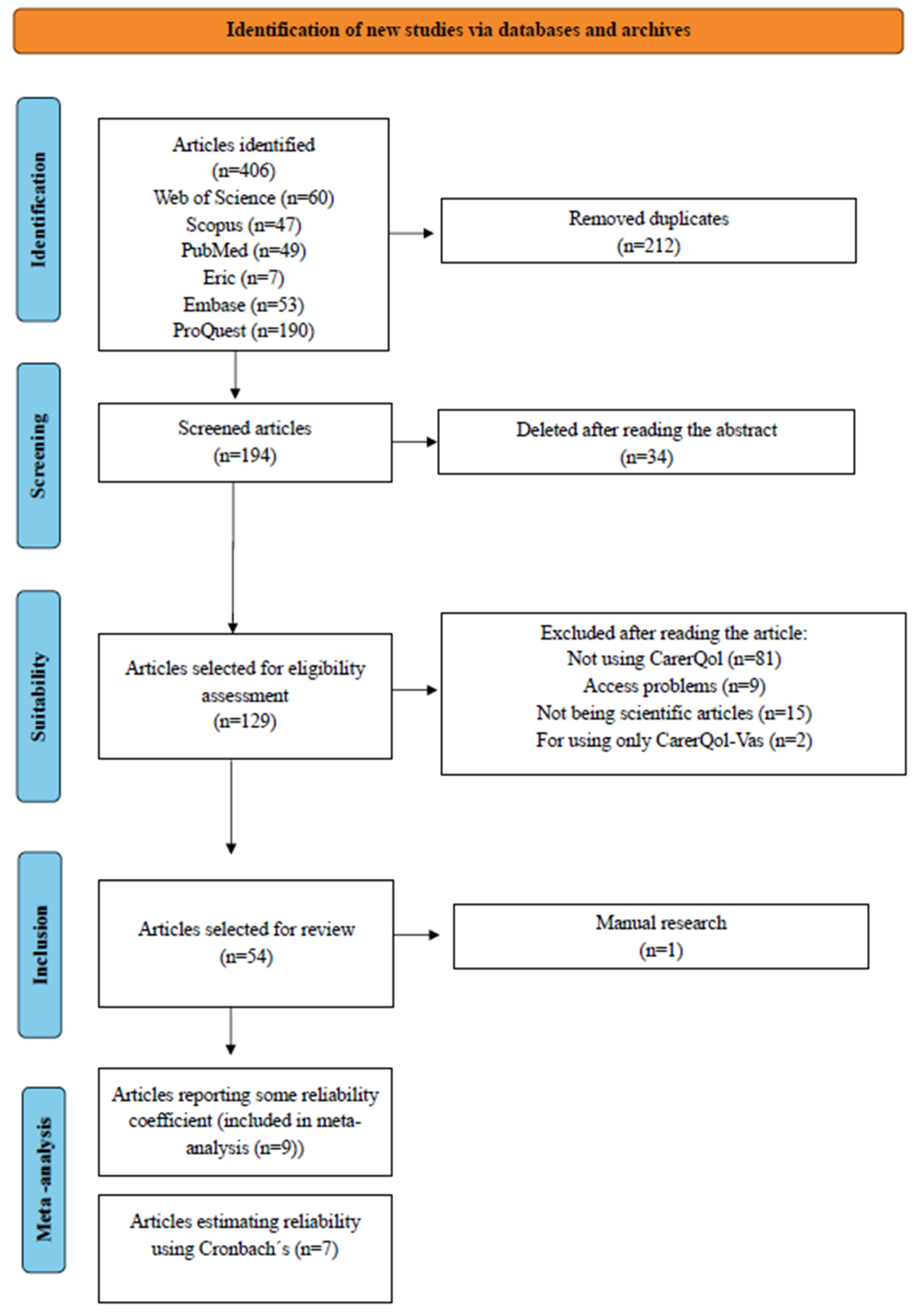

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Screening Conducted

2.6. The Information Extracted from the Studies

2.7. Validity Analysis Study

2.8. Reliability Estimates

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

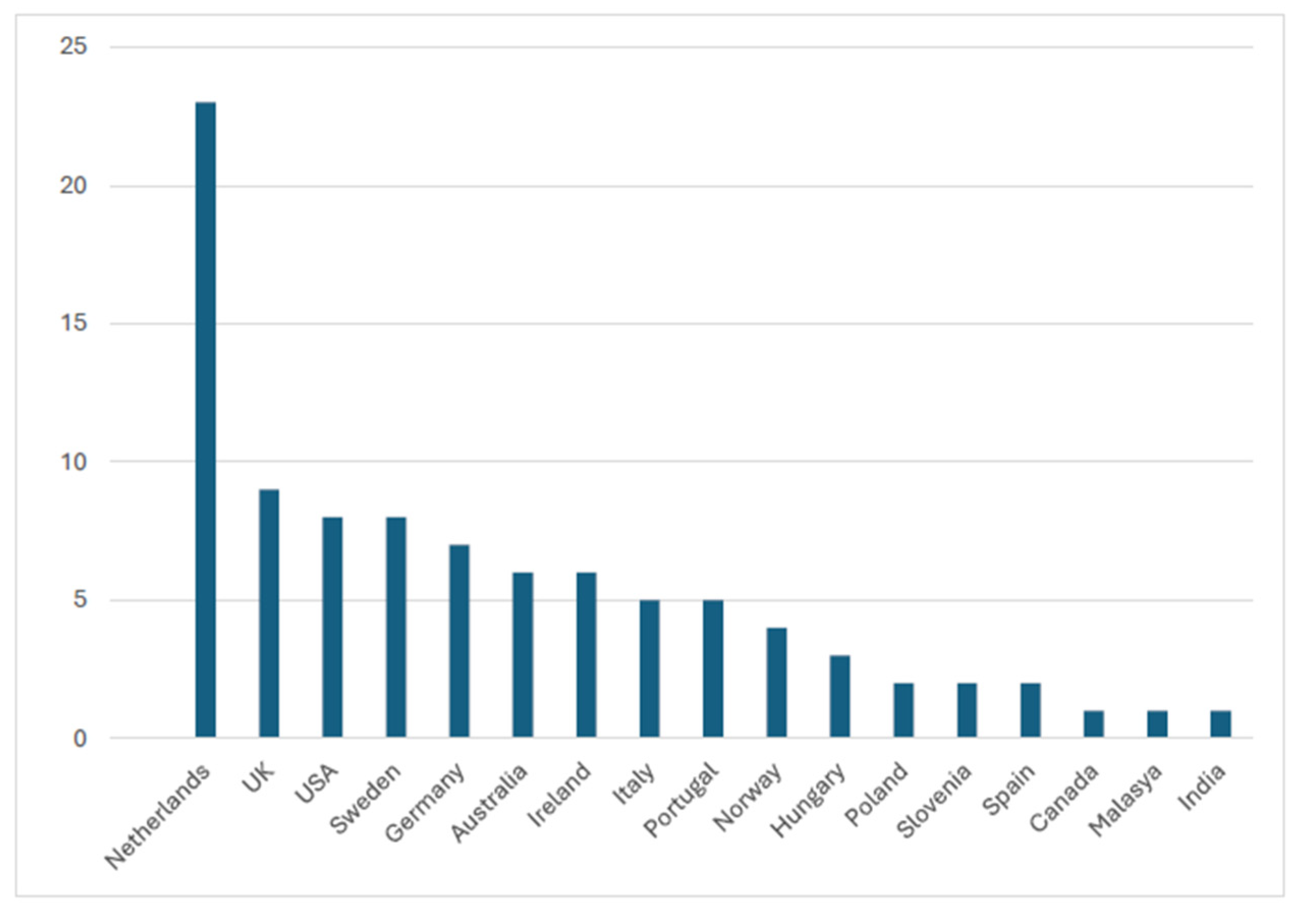

3.1. Methodological Aspects of Analyzed Studies

3.2. The Characteristics of the Caregiver Samples Included in the Study

3.3. Psychometric Properties of CarerQol Instrument

3.3.1. Validation Studies

3.3.2. Convergent Validity

3.3.3. Clinical Validity

Age

Gender

Paid Employment

Frequency of Caregiving

Living with the Caregiver

Satisfaction

Relational Problems and Higher Caregiving Tasks

Health

Other Factors

3.3.4. Discriminant Validity

3.3.5. Feasibility of CarerQol

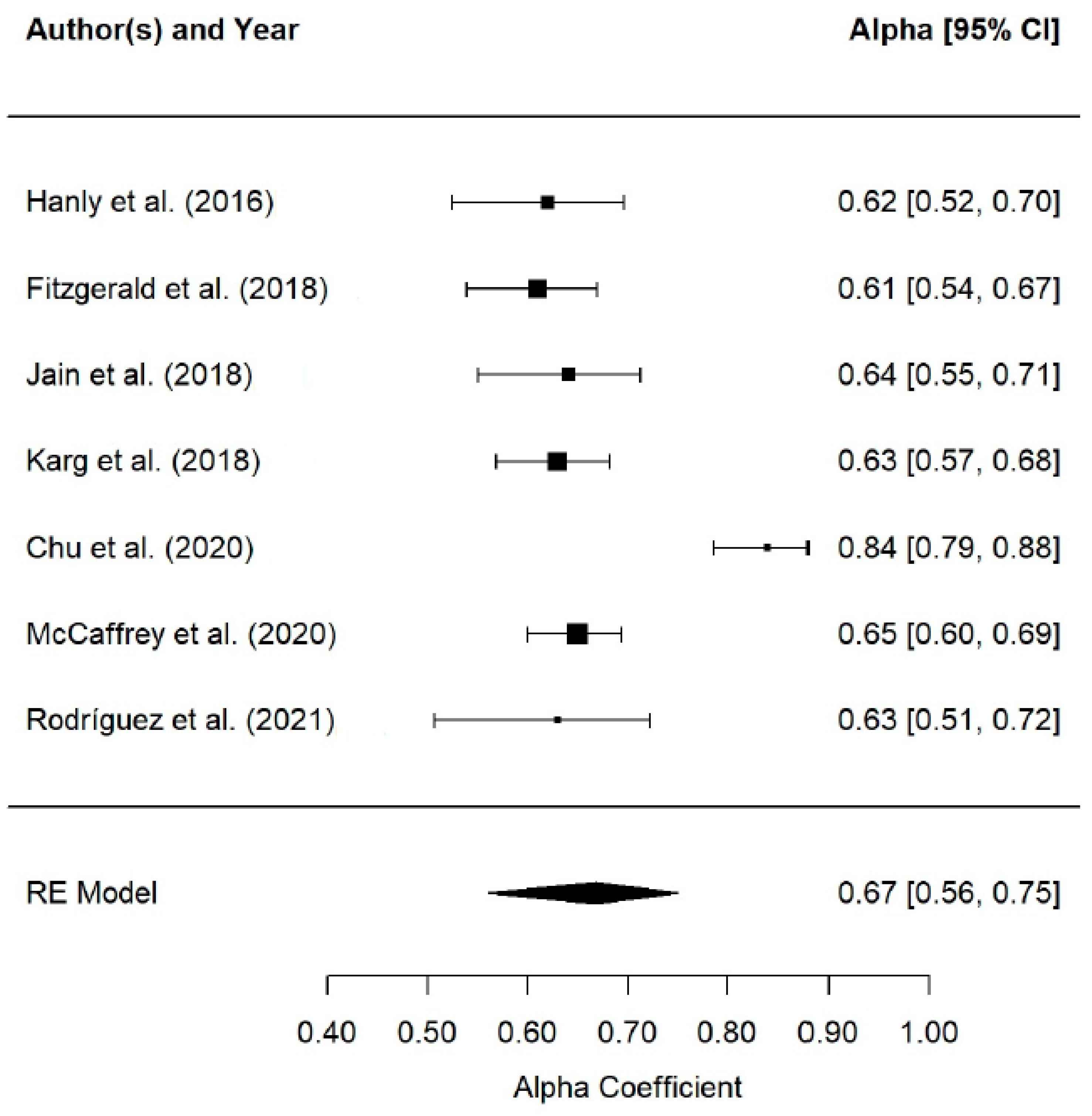

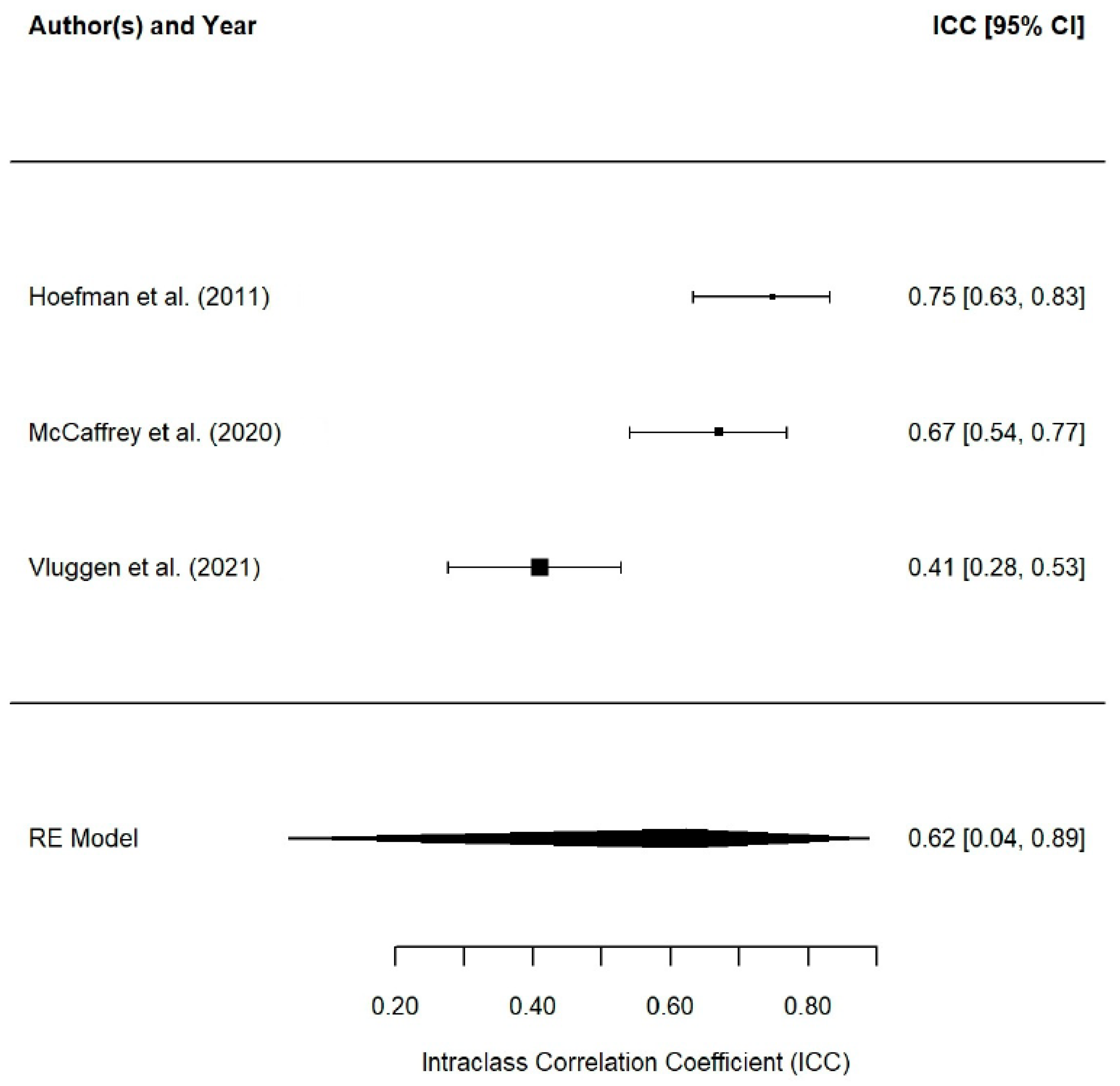

3.3.6. Reliability Study of the Instrument

3.3.7. Valuation Studies

CarerQol-7D Tariffs

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

4.1.1. Methodological Limitations

4.1.2. The Limitations of the Study

4.1.3. Limitations of the Instrument

4.1.4. Study Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CarerQol | Care-related Quality of Life instrument |

| CSI SCQ | Caregiver Strain Index |

| CES | Carer Experience Scale |

| SRB | Self-Rated Burden |

| ASCOT-Carer | Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit for Carers |

| PU | Process Utility |

| ASIS | Assessment of the informal care situation scale |

| ICECAP-A | ICEpop CAPability measure for Adults |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Author and Year | Location | Sample | Research Design and Sampling | Cared Group | Kind of Caregiver | Average Age (of) | Gender | Ethnicity | Level of Education | Type of Study | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | Netherlands | 175 (regional centers) | Cross-sectional design; sampling NP (for convenience) | NR | Informal | 60.8 (13.1) | M:25%; W:75% | NR | Low: 45%/Medium: 34%/High: 21% | Psychometric | eExcellent viability of the instrument. Excellent convergent validity between the relationships of the two parts of the CarerQol instrument, CSI, SRB, and PU. | The reliability of the instrument was been measured. Relatively short study. |

| [8] | Netherlands | 230 (regional carer support centers) | Cross-sectional design; P sampling (simple random) | Sick and/or disabled people | Informal | 58.74 (12.74) | M:25.7%, W:74.3% | NR | Low:13.1%/ Medium: 61.6%/ High:25.3% | Psychometric | After measuring clinical and convergent validity (associations with SRB and PU), the CarerQol instrument details the effect of caregiving. | Non-representative sample of the Dutch informal carers population. Lack of response. |

| [44] | Netherlands | 108 (people using nursing home care) | Longitudinal design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Elderly people | Informal | 59.1 (11) | M:28.6%; W:71.4% | NR | Low: 16.5%/Medium: 56.7%/High:29.5% | Psychometric | The CarerQol instrument assesses the effect of care in a feasible, valid, and reliable way. Shows good convergent (SRB and ASIS) and clinical validity. | Small sample size. Lack of responses. |

| [41] | US | 65 (Arkansas Reproductive Health Monitoring System) | Cross-sectional prospective design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Children with cranioencephalic malformations | Informal | 31.9 (5.3) | M:1.6%; W: 98.4% | Caucasian: 89.2%/Afro-American:6.2% /Other:4.6% | Low:24.6%/ High:76.4% | Psychometric | Acceptable construct validity; moderate associations of CarerQol-7D and CES-D, and high negative correlations between CarerQol-VAS and CES-D. | Small sample size. |

| [77] | Netherlands | 80 (home ventilation centers) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Informal | 57 (6.8) | M: 31%; W:69% | NR | Low:68% High: 32% | Applied | Substantial burden, which was associated with the support received, the tracheotomy, coping, and anxiety. However, care provision is valued as rewarding. | The cross-sectional design only allows associations to be detected. Sample selection bias. Findings not applicable to other populations. |

| [78] | Sweden | 118 (psychiatric outpatient centers) | Cross-sectional design (descriptive and methodological); NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients with psychosis | Informal | 58 (15) | M:33% W:67% | NR | NR | Applied | Caregivers perceived a greater burden and underestimated the time spent on caregiving. This situation caused them psychological distress. | A comparative group was not used. |

| [45] | Netherlands | 1244 (selected from general population) | Cross-sectional design; P sampling (simple random) | People with disabilities | Informal | NR | M:41.7%; W:58.3% | NR | Low:14.6%/ Medium:55.9%/ High:29.6% | Psychometric | This study confirmed the findings of previous studies regarding clinical validity and convergent and discriminative validity, expanding the sample of caregivers. | Selection bias. Validation is an ongoing process, and it is desirable to test psychometric properties among caregivers in other settings. |

| [79] | Netherlands | 67 (by center) | Cross-sectional design; P sampling (simple random) | Patients suffering from Pompe | Informal | NR | M:40%; W:60% | NR | NR | Applied | Greater burden associated with service hours; higher with patients with lower QoL. Caregivers reported mental health and ADL problems. However, they reported receiving satisfaction from care delivery. | Reduced number of patients. Selection bias. |

| [26] | USA | 310 (recruited from different associations) | Cross-sectional study; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients suffering from hemophilia | Informal | NR | M:10.7% W:89.4% | NR | Low:11.0%/ Medium:26.5%/ High:62.6% | Applied | Caregivers of children with inhibitors had a higher burden than those without inhibitors. Those caregivers of patients with inhibitors noticed a lower QoL. | Bias in study results. |

| [80] | USA | 304 (recruited from different associations) | Single assessment cross-sectional study; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients suffering from hemophilia | Informal | NR | G 1: M:20%/W:80% G2: M:9.9%/W:90.1% | NR | Group 1: Medium:6.7%/High:93.3%//Group 2: Low: 0.7%/Medium: 10.6%/High: 88.7% | Applied | Caregivers reported limited burden. However, caregivers reported satisfaction with care tasks. | Responses not representative. Bias in results. |

| [27] | Netherlands | 992 (adult population of the Netherlands) | Cross-sectional design; sampling P (simple random) | NR | Informal | 49.2 (16) | M:39.9% W:60.1% | NR | Low: 19.1%/Medium: 52.7%/High: 28.2% | Applied | The most important usefulness dimensions of care situations for this country were satisfaction followed by relational problems. Physical health is more substantial if coupled with mental health problems. | The group in this study is not considered representative of the population of the Netherlands, as women were overrepresented. |

| [80] | US | 224 (two autism treatment network sites) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Children with ASD | Informal | 39.4 (8.3) | M:11% W:89% | NR | Low: 12% High:88% | Applied | Carers’ burdens were lower when they received support, were satisfied with caregiving, and felt well. In contrast, they were higher when there were problems related to mental health, problems related to physical health, financial problems, and problems in balancing caregiving with daily activities. | Overrepresented patients. Bias in results. |

| [81] | Netherlands | 159 (by patients) | Longitudinal design; sampling P (simple random) | Elderly with frailty | Informal | EG: 60.7 (12.2)/CG:65.6 (11.2) | M:27% W:73% | NR | Experimental: Low: 65.4%/High: 34.6% Control: Low:(66.2%)/High (33.8%) | Applied | CarerQol showed that there was a reduction in subjective burden, and that carers had fewer problems as a result of the intervention. | Low proportion of variance explained by the intervention. The control variables had a low contribution. Lost to follow-up. |

| [82] | Netherlands | 223 (Netherlands’ register of dementia carers) | Transverse design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients suffering from dementia | Informal | 66.4 (13.4) | M:34.5% W:65.5% | NR | Low: 12.6%/Medium: 58.7%/High:28.7% | Applied | Caregivers experience certain problems in the relationship with the patient, the combination of ADL, and with their own mental health. However, the majority experienced satisfaction in the care and support of the immediate circle. | Small and selective sample. |

| [83] | USA | 224 (centers for children with ASD and their caregivers) | Cross-sectional design, with a triangulation mixed-methods approach; NP sampling (for convenience) | Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | Informal | 39.4 (8.3) | M:10.5% W:89.5% | Caucasian:72.8%/African American:9.4%/Hispanic:10.8% | Low:8.5% High:91.5% | Applied | The health of the caregivers was lower than the normative population. The caregivers of these children suffered from social anxiety and stress. | There is no control group. No information is provided about the income of the family. |

| [84] | Spain | 202 (registry of caregivers) | Cross-sectional design; sampling P (simple random) | NR | Informal | 47.8 (12.8) | M:31.7% W:68.3% | NR | Low: 45.1%/Medium:28.2%/High:26.8% | Applied | A monetary valuation was carried out between caregivers and non-caregivers, showing that it is possible to receive a monetary value for informal care from the non-carers’ preferences. | Relatively small sample size. No representation of caregivers. |

| [31] | South Australia | 97 (carers associated with Southern Adelaide Palliative Services) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients at the end of life | Informal | 62.3 (11.9) | M:29% W:71% | Australian/European: 98%/Asian:1% | NR | Psychometric CarerQol | Shows good convergent validity (PU and CSI), clinical validity, and discriminative validity. | The sample size was small. Caregivers were predominantly older women. |

| [85] | USA | 224 (treatment centers) | Cross-sectional, prospective design study; NP sampling (for convenience) | Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | Informal | 39.4 (8.3) | M:10.5% W:89.5% | Caucasian: 72.8%/African American:9.4%/Hispanic: 10.8%/Asian:3.3%/Other: 3.3% | NR | Applied | Negative effects on QoL and well-being associated with sleep problems in children. Caregivers who slept ≤ 5 h showed scores that suggested the presence of more depressive symptoms and worse QoL. | Cross-sectional design to quantify QALYs. Direct measures were not used in certain processes in the study. |

| [55] | Ireland | 180 (caregivers of people enrolled in the Irish National Cancer Registry) | Cross-sectional design study of a descriptive and correlational nature; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients with head and neck cancer | Informal | 57.3 (12.5) | M:24% W:76% | NR | NR | Applied | Caregivers experienced satisfaction with their care tasks and high levels of happiness. Almost half reported mental and physical health problems. | Cross-sectional nature indicates that no causality claims can be made. CarerQol-VAS was not specific to cancer carers. |

| [86] | Netherlands | 356 (test phase); 158 (post-test phase) (through the organizations of the Elderly Care Network) | Longitudinal design; NP sampling (convenience) | Older adults | Informal | 63.2 (11.4) | M:32% W:68% | NR | NR | Applied | Carers reported problems related to physical and mental conditions as well as daily activities. The burden was higher when the cared-for person’s health was worse. | Limitation when it comes to generalizing the results. |

| [87] | UK | NR | Longitudinal design/probability (random) sampling | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Informal | NR | NR | NR | NR | Applied | This study lacks necessary information on valid therapeutic protocols for people with DMD and their caregivers. | NR. |

| [60] | Australia, Germany, Sweden, UK, and USA | Australia: 551/Germany: 562/Sweden: 548/UK: 552/USA 550 | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Care | scenarios Informal | Australia:45.5 (16.4)/Germany:46.7 (16.3)/Sweden:47.3 (17.5)/:UK:46.6 (16.7)/USA: USA:45.8(16.9) years | M:Australia:48.8/Germany:48.4/Sweden:49.1/UK:48.4/USA:48.6% W:Australia:51.2/Germany:51.6/Sweden:50.9/UK:51.6/USA:51.5% | NR | Low: Australia:1.1/Germany:21.2/Sweden:17.9/UK:20.7/USA:13.3// Medium: Australia:67.7/Germany:55.7/Sweden:49.6/UK:23/USA:28.2//Raised:Australia:31.2/Germany:23.1/Sweden:32.5/UK:56.3/USA:58.6 | Applied | The most important utility dimension for caregiving situations was physical condition, but the least important dimensions were support and difficulty in combining care with daily activities. | Heterogeneity in preferences for care situations. The study sample could be somewhat selective. |

| [88] | Germany, Italy, Ireland, Norway, Netherlands Sweden, Portugal, and the UK | 453 (campaigns, case managers, general practices, memory clinics, and community teams) | Cross-sectional prospective cohort design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients suffering from moderate or severe dementia | Informal | 66.4 (13.3) | M:33.4% W:66.6% | NR | NR | Applied | Married women had a higher burden compared to other family members. Adaptation to change was associated with better health. | Determination of causality is limited. Cultural backgrounds in different countries may influence caregiver behaviors. |

| [39] | Netherlands | 5197 (NR) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Older adults | Informal | 80.7 (7.25) | M:38% W:62% | 94% native | Low:44%/ Medium:51%/ High:5% | Applied | Caregivers produced a high burden and reduced QoL. This situation was accentuated in female carers. | Problems with generalizability of results. Relatively high non-response on some items. |

| [89] | Netherlands | 660 (NR) | Longitudinal design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Elderly people with frailty | Informal | 65 (12.6) | M:32% W:68% | NR | NR | Applied | A worse symptomatology of the patient was related to a worse QoL of the caregiver and with the presence of more problems related to mental and physical conditions, and with combining care with daily activities. | Abandonment of certain subjects in the sample. Selection bias. |

| [46] | Netherlands | 1 = 198 /2 = 166 (1. Regional Assessment Agency; 2. Community Caregivers) | Study 1: longitudinal; Study 2: cross-sectional; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients with dementia | Informal | : 66.6 (12.9)/Study 2: 49.5 (14.4) | M: E1:1:33%/E2:45% W: E1:67%/E2: 55% | NR | NR | Psychometric | Good construct validity between the associations of CarerQol with SRB and CSI. | Divergence between the two study populations. |

| [9] | Sweden | 97 (newspapers, social networks, and organizations with interests in caregivers) | Longitudinal design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients with mental illness | Informal | NR | M:11% W:89% | NR | Medium:13%/High:83%/Other:4% | Applied | Caregiver burden, in most aspects, did not show significant improvements after the intervention, except in the relational dimension. | Some participant dropouts. It is difficult to know whether any confounding factors may have influenced the results. |

| [90] | Sweden | 151 (NR) | Longitudinal design; NP sampling (for convenience) | People suffering from mental illness | Informal | 54 (NR) | M:EG:10%/CG:14% W:EG:90%/CG:86% | NR | EG: Medium:14% /High:82% /Other:4%//CG: Medium:22% /High:73% /Other:5% | Applied | The comparisons between the groups before and after the intervention showed improvements in favor of the experimental group in terms of relational problems, problems related to mental health status, and daily activities. | Dropout rate. It is difficult to know whether any confounding factors may have influenced the results. |

| [91] | Netherlands | 350 (via care recipients) | Cross-sectional design; sampling NP (snowball) | NR | Informal | 63 (13.3) | M:33.8% W:66.2% | NR | NR | Applied | Many carers stated that they would be less happy if the care of the dependent person was performed by someone else. QoL depended on variables such as health, disease deterioration, or happiness. | Overestimation of caregiver quality of life in informal caregivers. |

| [92] | Netherlands | 123 (through care recipients) | Cross-sectional study; P sampling (simple random) | Elderly patients with hip fracture | Informal | 64.6 (12.2) | M:44.7% W:55.3% | NR | Low:30.1%/Medium: 45.5%/High:24.4% | Applied | Those patients who showed cognitive impairment had a lower QoL. Relational problems were experienced by caregivers. Women have a higher burden. | Non-response bias. The cross-sectional nature indicates that causality claims cannot be made. |

| [54] | Ireland | 326 (caregivers enrolled in the Irish Comparative Outcomes Study) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Children suffering from cystic fibrosis | Informal | M: = 35.5 (4.8), H = 38.0 (5.4) | M:42.02% W:57.98% | NR | High: Women (68%) and Men (53.9%)//Medium: Women (32%) and Men (46.1%) | Applied | A large proportion of caregivers reported mental health problems. People who are severely depressed adhere less well to treatment. Burden on caregivers increases as children age. | The instrument is not valid for caregivers of people with CF, and it is the first time it has been used in this population. Limitation of sample. |

| [93] | Germany, Italy, Ireland, Norway, Portugal, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK | 451 (NR) | Cross-sectional design; P sampling (simple random) | Patients with dementia | Informal | 66 (13) | M:33% W:67% | NR | NR | Applied | Non-medical costs (i.e., social services and informal care) were a relatively great proportion of costs/QoL of caregivers was reduced. | Representativeness limited by relatively small sample sizes from each country. |

| [56] | Canada | 181 (different centers in Canada) | Cross-sectional prospective cohort design; sampling NR (for convenience) | Children with drug-resistant epilepsy | Informal | NR | M:16% W:84% | NR | High: 78.5%/ Low: 21.5% | Applied | QoL of caregivers was higher when QoL of patients was favorable. In contrast, a lower QoL was linked to the occurrence of depressive and anxious symptoms. | NR. |

| [57] | Germany | 386 (Bavarian Compulsory Health Insurance Fund Medical Service) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (by trial) | Patients with dementia | Informal | 61.3 (12.2) | M:24% W:76% | NR | NR | Applied | Carers of people with dementia showed a high subjective burden and high levels of depression. | Certain care-related variables that might be of interest were not measured. The cross-sectional nature indicates that no claims of causality can be made. |

| [94] | Netherlands, Norway, Germany, the UK, Sweden, Ireland, Italy, and Portugal | 451 (recruited from memory clinics and community mental health teams) | Cross-sectional prospective cohort design; NP sampling (convenience) | Patients with dementia | Informal | 66.4 (13.3) | M:33% W:67% | NR | NR | Applied | The greater the needs, the worse the quality of life. | Selection bias. |

| [38] | The Netherlands | 6 (via Radboud University Medical Center and Erasmus Medical Center) | Observational study, cross-sectional design; NP sampling (convenience) | Patients suffering from cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome | Informal | NR | NR | NR | NR | Applied | Informal caregivers showed a higher subjective burden than the general Dutch population. They also indicated mental health-related problems due to the care provided. | Relatively small sample. |

| [95] | Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia | 395 (NR) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (by quotas) | Hypothetical care situations | Informal | Hungary: 56.1 (NR)/Poland: 45.6 (NR), Slovenia:48 (NR) | M: Hungary:41.6%/Poland:50%/Slovenia:49% W: Hungary: 58.4%/Poland:50%/Slovenia:51% | NR | :HU:18.8%/PO:7.3%/ES:11.5%/Medium:HU:36.9%/PO:60, 7%/ES:61.5%/ High:HU:44.3%/PO:32.0%/ES:27.1% | Applied | Most caregivers were satisfied with the care. In both Hungary and Slovenia, problems in combining care with ADL were the most prominent. Women were more likely to be caregivers in Hungary. | Over-representation of certain population groups. |

| [52] | Australia | 40 (general and psychogeriatric nursing homes) | Longitudinal design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients suffering from dementia | Informal | Group A: 67.7 (12.6)/Group B: 59.6 (6.8) | M:15% W:85% | NR | Group A: Low (10%) Medium: (12.5%) High: (27.5%) Group B: Low(22.5%) Medium: (12.5%) High: (15%) | Applied | The effect on the caregivers after the intervention was limited and there were no major changes among the conditions for the quality of the relationship of caregiver–person cared-for and caregivers’ sense of mastery and reported QoL. | Small sample size. Differences in the characteristics of the caregivers in both groups. |

| [96] | UK and USA | 56 (NR) | Observational study with a cross-sectional design; P-sampling (random) | Patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy | Informal | NR | M:40% W:60% | White:98%/African American:2% | Low:11%/ Medium:52%/ Superior: 37% | Applied | CarerQol only measured caregivers’ happiness, which reported high values. | Relatively small sample. |

| [61] | Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia | n = 1000 HU/n = 1000 PO/n = 1000 ES (NR) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (by quotas) | Care | Informal | 53.2 ± (15.1) Hungary, 45.1 ± (15.7) Poland 46.4 ± (16.0) Slovenia | M:48.8% HU/47, 5%PO/47.6% ES W: 51.2% HU/52.5%PO/52.4% ES | NR | Hungary: Low:23.1%/Medium:37.4%/High:39.5%//Poland: Low:11.1%/Medium: 66.7%/High:22.2%//Slovenia: Low:17.6%/Medium:55.8%/High:26.6% | Applied | In Hungary and Slovenia, physical health and mental health problems contributed the most to the utility score, followed by satisfaction. In Poland, satisfaction was the most important domain. | Sample selection bias and standard errors. |

| [97] | East India | 324 (thalassemia outpatient department (OPD)) | Observational study with cross-sectional design; NP (convenience) sampling | Older children with beta-thalassemia | Informal | 31.8 (6.3) | M:24.1% W:75.9% | NR | Low: 66.4%/ Medium:19.8%/ High: 13.8% | Applied | Thalassaemia generates stress and strain that affects the quality of life of support persons. The caregivers of these people had a significantly high burden due to caregiving. | The cross-sectional design did not allow causal associations to be established. Much of the data were self-reported by caregivers. |

| [98] | Portugal | 36 (caregivers of Body & Brain project participants) | Longitudinal design; NP (convenience) sampling | Patients with dementia | Informal | 64.94 (13.54) | M:58.29% W:41.71% | NR | Medium: 27.8%/High:72.2% | Applied | Caregiver burden increased significantly during home confinement. Self-assessed well-being of caregivers decreased. Decreased perceived satisfaction and support. | Small sample size. Difficulty in generalizing the results. |

| [53] | Malaysia | 110 (caregivers attending therapy at the University of Malaysia Speech and Audiology Clinic) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | Informal | NR | M:27.3% W:72.2% | Malays (93.6%)/Chinese/(5.5%)/Indians (0.9%) | Low:0.9%/ Medium:18.2%/High:77.3%/ Others:3.6% | Applied | The main drawback is related to relational problems with the child and mental health problems. Happiness levels reported by caregivers were moderate. | NR. |

| [99] | Australia | 351 (through Carers Victoria non-profit organization) | Cross-cutting design; sampling NP (by trial) | NR | Informal | 53 | M:20% W:80% | NR | Low: 18%/ Medium: 8%/ High:73%/ Other:1% | Psychometric | Factor analysis indicates that the measures of the different instruments assess different aspects and provide unique information (CarerQol, ASCOT-Carer, CES). | Inconsistent responses. |

| [100] | Australia | 43 (via Myeloma Australia) | Cross-sectional design; sampling NP (for convenience) | Patients suffering from multiple myolemma | Informal | NR | M:30.24% W:69.76% | NR | NR | Applied | The subjective burden experienced by caregivers of patients with multiple myolemma was relatively high. The well-being experienced by the caregivers was medium. | Sampling problems. |

| [101] | UK, Italy, and Germany | 585 (NR) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients with atrial fibrillation | Informal | 46.8 (15.6) | M:42.2% W:57.6% | NR | Low: 4.3%/Medium: 46.2%/High:49.6% | Applied | Most carers expressed satisfaction with care. Many of them had problems affecting their mental and physical health and also reported problems in ADL. | Sample made up of self-reported caregivers. Selection bias. |

| [48] | Australia | 500 (carers registered with Carers Victoria) | Cross-sectional study; sampling P (random) | NR | Informal | 52 (14) | M:21% W:79% | 80% Australians | Low: 18%/ Medium:10%/ High:71%/ Other:1% | Psychometric | Good discriminative and convergent validity, analyzed through the associations of CarerQol with ASCOT and CES-D. | NR. |

| [47] | UK | 576 (via NatCen Social Research) | Longitudinal design; NP sampling (by trial) | Dementia patients | Informal | 62 (11) | M:35% W:65% | NR | NR | Psychometric | Good convergent validity, analyzed between the correlations of CarerQol with ASCOT, EQ-5D-5L, and ICECAP. | Loss of subjects throughout the study. |

| [102] | Netherlands | 81 (caregivers more involved in in the care of children with autism spectrum disorder) | Multicentre prospective cross-sectional design study; NP sampling (for convenience) | Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | Informal | NR | NR | NR | NR | Applied | Caregivers reported problems with the cared-for child and complexity in combining care with their daily duties. The QoL of caregivers is lower. However, they reported satisfaction and support with care. | Relatively small sample. The subjects in this study are not characteristic of the total group of children with ASD and their support persons. |

| [50] | Hungary | 149 (NR) | Cross-sectional study; sampling P (random) | NR | Informal | 56.1 (14.2) | M:41.6 W:58.4 | NR | Low: 44.3%/Medium: 36.9%/High: 44.3% | Psychometric | Good convergent, clinical, and discriminant validity of the Hungarian version of CarerQol and supports the cross-cultural. validity of the instrument. | Sampling problems. |

| [103] | Netherlands | 42 (through organizations working with people with dementia and their carers) | Longitudinal design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Patients with mild dementia | Informal | 62.8 (13) | M:26.2% W:73.8% | NR | Low: 50%/Medium: 30%/High: 20% | Applied | Caregivers did not perceive much distress and reported relatively high QoL. | Bias in the study sample. |

| [58] | Spain | 110 (NR) | Cross-sectional design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Children with neuromuscular diseases | Informal | 44.7 (7.2) | M:17.2% W:82.8% | NR | Low:13.7%/Medium: 24.6%/High:61.7% | Applied | Children with a higher level of dependency generated higher costs. The most affected carers are those who are unemployed, those with low sources of income, and those whose children had a high level of dependency. Women had the highest score in somatic symptoms. | Non-homogeneous groups. Cause and effect cannot be inferred. |

| [59] | Netherlands | 172 (caregivers of patients attending geriatric rehabilitation units) | Longitudinal design; P sampling (simple random) | Patients who have suffered stroke | Informal | Intervention group: 61.0 (13.5)/Usual care group: 60.5 (13.5) | M: Intervention group: 35.4%/Usual care group: 29.3%//W: Intervention group: 64.6%/Usual care group: 70.7% | NR | NR | Applied | The integrated program resulted in a decrease in caregiver burden. Stroke education helps informal caregivers fulfill their support role. | Sampling bias. |

| [49] | Germany, Italy, Norway, Sweden, Portugal, the Netherlands, the UK, and Ireland | 433 (NR) | Prospective longitudinal design; NP sampling (for convenience) | Dementia patients | Informal | 66.2 (13.4) | M:34% W:66% | NR | Low (56.3%)/High (43.7%) | Psychometric | The results support that CarerQol shows good clinical and convergent validity (associations of CarerQol with ICECAP and EQ-5D). | Convenience sampling may have underrepresented burdened caregivers who were unable to participate in this study. |

| Type of caregiver | In all studies (n = 54), caregivers were informal; formal caregivers were not included. |

| Caregivers’age | Mean: 58.7 years (SD = 11.92). Range: 31.8 years [97] (caregivers of children with beta-thalassemia) to 80.7 years [39] (caregivers of adults with disabilities). Younger caregivers were mostly parents, while older caregivers were often spouses. |

| Caregivers’gender | In 92.5% of the studies, female caregivers were the majority. A total of 5.66% did not report gender [104]. Only 1.9% of the studies had more male caregivers (58.3% caring for people with dementia) [98]. The most significant gender gap was found in Payakachat et al., with only 1.8% male caregivers [41]. |

| Educational | Education was reported in 62.26% of the studies. A total of 28.25% had a “low” education level (primary school), 39.68% had a “middle” level (secondary school), and 31.94% had higher education. A total of 0.13% were classified as “others”. |

| Caregivers’ethnicity | Only 15.1% of the studies (n = 8) reported ethnicity. Most (n = 7) had a higher percentage of White/Caucasian individuals. In Chu et al., 93.2% were Malaysian, 5.5% Chinese, and 0.9% Indian [53]. |

| Author | Sample (n) and Gender Distribution | Psychometric Properties | Measurement of Convergent | Validity Background Variable Clinicals | Validity Discriminative Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | n = 175 caregivers (Mixed) | Feasibility, clinical and convergent validity | Spearman’s correlation with CSI relational problems and CSI (r = 0.49), mental health problems and CSI (r = 0.42), problems with activities daily problems and CSI (r = 0.50), financial problems and CSI (r = 0.28), and physical problems and CSI (r = 0.40). Satisfaction and CSI (r = −0.20); 2. support and CSI (r = −0.21) | Frequency of care and coexistence. | NR |

| [41] | n = 65 caregivers (Mixed) | Convergent validity | Spearman’s rho with CES-D CarerQol-7D with CES-D (r = 0.65) CarerQol-VAS with CES-D (r = −0.74) | NR. | NR |

| [44] | n = 230 caregivers (Mixed) | Convergent validity, and clinical validity | Spearman’s correlation with SRB and PU CarerQol-7D with CarerQol-VAS: relational problems (r = −0.34); problems associated with mental health (r = −0.56); problems in reconciling care with activities of daily living (r = −0.44); economic problems (r = −0.19); problems related to physical condition (r = −0.44). CarerQol-VAS with SRB (r = −0.45) SRB with satisfaction (r = −0.27); and 2. support (r = −0.03). PU with satisfaction (r = 0.37) and 2. support (r = 0.15) | Satisfaction, burden, tie, and intensity. | NR |

| [8] | n = 108 caregivers (Mixed) | Feasibility, convergent validity, and clinical validity | Spearman’s correlation with SRB y ASIS CarerQol-VAS and satisfaction (r = 0.15) and support (r = 0.05) SRB and support (r = −0.06) ASIS and satisfaction (r = 0.27) and support (r = 0.13) | Tie, age, years caring, intensity, remuneration, and education. | NR |

| [45] | n = 1244 caregivers (Mixed) | Convergent validity, clinical validity, and discriminative validity | Spearman’s correlation with SRB, ASIS, PU y CSI CarerQol-VAS, and satisfaction (r = 0.24) and support (r = 0.14) ASIS and satisfaction (r = 0.24) and support (r = 0.13) and with CarerQol-VAS (r = 0.31) PU with satisfaction (r = 0.31), 2. support (r = 0.09) and CarerQol-VAS (r = 0.52) SRB with relational problems (r = 0.35), problems associated with mental health (r = 0.39), problems in reconciling care with activities of daily living (r = 0.47), economic problems (r = 0.30) and problems related to physical condition (r = 0.42) SRB with CarerQol-VAS (r = −0.33) CSI with relational problems (r = 0.38) problems associated with mental health, (r = 0.47), problems in reconciling care with activities of daily living (r = 0.52), economic problems (r = 0.42) and problems related to physical condition (r = 0.48); the relationship with CarerQol-VAS was negative (r = −0.40). | Gender, job, and health. | YES |

| [31] | n = 97 caregivers (Mixed) | Convergent validity, clinical validity, and discriminative validity | Spearman’s correlation with PU, CSI CarerQol 7-D with CarerQol-VAS (r = 0.60) CarerQol-7D and PU (r = 0.62) CarerQol-7D and CSI(+) (r = 0.55) CarerQol-7D and CSI(−) (r = −0.67) | Years of care, caregiver and patient health. | YES |

| [46] | n = 198 y n = 166 caregivers (Mixed) | Convergent validity | Spearman’s correlation with SRB y CSI (NR) | NR. | NR |

| [99] | n = 351 caregivers (Mixed) | NR | NR | NR. | NR |

| [48] | n = 500 caregivers (Mixed) | Convergent and discriminative validity | Spearman’s correlation with ASCOT y CES-D CarerQol-7D and ASCOT-Carer (r = 0.54) CarerQol-7D and CES-D (r = 0.45) | NR. | YES |

| [47] | n = 576 caregivers (Mixed) | Convergent validity | Spearman’s correlation with ASCOT, EQ-5D-5L y ICECAP CarerQol with ASCOT-Carer (r = 0.71), with EQ-5D-5L (r = 0.0.51) and with ICECAP-A (r = 0.69) | NR. | NR |

| [50] | n = 149 caregivers (Mixed) | Convergent validity, and clinical validity | Spearman’s correlation with EQ-5D-5L and EQ VAS CarerQol 7-D with CarerQol-VAS (r = 0.363) CarerQol-7D with EQ-5D-5L (r = 0.453) CarerQol-7D with EQ VAS (r = 0.387) CarerQol-VAS with EQ-5D-5L (r = 0.453) CarerQol-VAS with EQ VAS (r = 0.242) | Care situation, caregiver and patient health, and years of care. | YES |

| [49] | n = 433 caregivers (Mixed) | Convergent validity, and clinical validity | Spearman’s correlation with ICECAP y EQ-5D CarerQol-VAS and CarerQol-7D: 1 satisfaction (r = 0.34) y 2. support (r = 0.15) EQ-5D and satisfaction (r = −0.09) and support (r = −0.13) | Gender, intensity, and health. | NR |

| 95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | k | N | Average | LL | LU | ANOVA Results |

| Mean age (years) | F(1, 37) = 0.54, p = 0.468 R2 = 0.0 QW(37) = 51855.57.3, p < 0.0001 | |||||

| Reported | 7 | 1782 | 53.08 | 44.45 | 61.70 | |

| Not reported | 32 | 19,453 | 56.52 | 52.49 | 60.56 | |

| Variance age (years) | F(1, 37) = 1.03, p = 0.317 R2 = 0.0 QW(37) = 3756.19, p < 0.0001 | |||||

| Reported | 7 | 1782 | 125.09 | 74.37 | 175.82 | |

| Not reported | 32 | 19,453 | 153.18 | 129.22 | 177.14 | |

| Male (%) | ||||||

| Reported | 9 | 25.39 | 18.13 | 34.33 | F(1, 48) = 0.79, p = 0.378 R2 = 0.37 QW(48) = 844.47, p < 0.0001 | |

| Not reported | 41 | 29.57 | 25.51 | 33.99 | ||

| TITLE | Yes | No | Page | NR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Title | x | 1 | ||

| ABSTRACT | Yes | No | Page | NR |

| 2. Abstract | x | 2 | ||

| INTRODUCTION | Yes | No | Page | NR |

| 3. Background | x | 3 | ||

| 4. Objectives | x | 7 | ||

| METHOD | Yes | No | Page | NR |

| 5. Selection criteria | x | 7 | ||

| 6. Search strategies | x | 8 | ||

| 7. Data extraction | x | 9 | ||

| 8. Reported reliability | x | 9 | ||

| 9. Estimating the reliability induction and other sources of bias | x | 9 | ||

| 10. Data extraction of inducing studies | x | 9 | ||

| 11. Reliability of data extraction | x | 9 | ||

| 12. Transformation method | NR | |||

| 13. Statistical model | x | 10 | ||

| 14. Weighting method | NR | |||

| 15. Heterogeneity assessment | x | 10 | ||

| 16. Moderator analyses | NR | |||

| 17. Additional analyses | NR | |||

| 18. Software | NR | |||

| RESULTS | Yes | No | Page | NR |

| 19. Results of the study selection process | x | 11 | ||

| 20. Mean reliability and heterogeneity | x | 21 | ||

| 21. Moderator analyses | x | |||

| 22. Sensitivity analyses | x | |||

| 23. Comparison of inducing and reporting studies | x | |||

| 24. Data set | x | |||

| DISCUSSION | Yes | No | Page | NR |

| 25. Summary of results | 28 | |||

| 26. Limitations | x | 26 | ||

| 27. Implications for practice | x | 26 | ||

| 28. Implications for future research | x | 26 | ||

| FUNDING | Yes | No | Page | NR |

| 29. Funding | x | 28 | ||

| PROTOCOL | Yes | No | Page | NR |

| 30. Protocol | x |

| Section and Topic | Item | Checklist | Location Where Item Is Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | 1 |

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | 2 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | 3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | 7 |

| METHOD | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses | 7 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | 8 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | 8 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 7 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 9 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | NR |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | 9 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | 9 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | NR |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)) | NR |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | NR | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | NR | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | 9 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression) | 10 | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results | NR | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | 10 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | 10 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | 13 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | 7 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | NR |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | NR |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | NR |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | NR |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | 21 | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | 21 | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | NR | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | NR |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | 22 | |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | 26 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | 26 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | 26 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | NR |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | NR | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | NR | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | NR |

References

- World Health Organization. Long-Term Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/long-term-care (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Cejalvo, E.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Merino-Soto, C.; Aguirre-Morales, M.T. Caregiving Role and Psychosocial and Individual Factors: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, A.; Lambert, S.; Johnson, C.; Waller, A.; Currow, D. Physical, psychosocial, relationship, and economic burden of caring for people with cancer: A review. J. Oncol. Pract. 2013, 9, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, D.; Shrestha, R.N.; Zeppel, M.J.B.; Cunich, M.M.; Tanton, R.; Veerman, J.L.; Kelly, S.J.; Passey, M.E. Economic costs of informal care for people with chronic diseases in the community: Lost income, extra welfare payments, and reduced taxes in Australia in 2015–2030. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosquera, I.; Vergara, I.; Larrañaga, I.; Machón, M.; del Río, M.; Calderón, C. Measuring the impact of informal elderly caregiving: A systematic review of tools. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 1059–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Exel, N.J.; Koopmanschap, M.A.; van den Berg, B.; Brouwer, W.B.; van den Bos, G.A. Burden of informal caregiving for stroke patients. Identification of caregivers at risk of adverse health effects. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2005, 19, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefman, R.J.; van Exel, N.J.; Foets, M.; Brouwer, W.B. Sustained informal care: The feasibility, construct validity and test-retest reliability of the CarerQol-instrument to measure the impact of informal care in long-term care. Aging Ment. Health 2011, 15, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stjernswärd, S.; Hansson, L. A web-based supportive intervention for families living with depression: Content analysis and formative evaluation. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2014, 3, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schulz, R.; Sherwood, P.R. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108 (Suppl. S9), 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A.; Brandt, M.; Hank, K.; Schröder, M. Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (HAREE) Study; Share-ERIC: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.share-project.org (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Department of Social Services. Carer Payment and Carer Allowance; Services Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2024. Available online: https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/carer-payment (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Bru-Luna, L.M.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Merino-Soto, C.; Salinas-Escudero, G.; Toledano-Toledano, F. Variables Impacting the Quality of Care Provided by Professional Caregivers for People with Mental Illness: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. What Is the Evidence on the Methods Frameworks and Indicators Used to Evaluate Health Literacy Policies Programmes and Interventions at the Regional National and Organizational Levels? World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326901/9789289054324-eng.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Brouwer, W.B.; van Exel, N.J.; van den Berg, B.; van den Bos, G.A.; Koopmanschap, M.A. Process utility from providing informal care: The benefit of caring. Health Policy 2005, 74, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Zemon, V.; Foley, F.W. Measuring personal growth in partners of persons with multiple sclerosis: A new scale. Rehabil. Psychol. 2020, 65, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.C. Validation of a Caregiver Strain Index. J. Gerontol. 1983, 38, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Janabi, H.; Coast, J.; Flynn, T.N. What do people value when they provide unpaid care for an older person? A meta-ethnography with interview follow-up. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, H.; Flynn, T.N.; Coast, J. Development of a self-report measure of capability wellbeing for adults: The ICECAP-A. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Exel, N.J.; Scholte Op Reimer, W.J.; Brouwer, W.B.; van den Berg, B.; Koopmanschap, M.A.; van den Bos, G.A. Instruments for assessing the burden of informal caregiving for stroke patients in clinical practice: A comparison of CSI, CRA, SCQ and self-rated burden. Clin. Rehabil. 2004, 18, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, W.B.; van Exel, N.J.; van Gorp, B.; Redekop, W.K. The CarerQol instrument: A new instrument to measure care-related quality of life of informal caregivers for use in economic evaluations. Qual. Life Res. 2006, 15, 1005–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EuroQol Group. EuroQol—A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, B.; Brouwer, W.B.; Koopmanschap, M.A. Economic valuation of informal care. An overview of methods and applications. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2004, 5, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmanschap, M.A.; van Exel, J.N.; van den Berg, B.; Brouwer, W.B. An overview of methods and applications to value informal care in economic evaluations of healthcare. Pharmacoeconomics 2008, 26, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Institute for Applied System Analysis. IVICQ Questionnaires; Institute for Medical Technology Assessment: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Available online: https://www.imta.nl/questionnaires/ivicq/documents/ (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- DeKoven, M.; Karkare, S.; Kelley, L.A.; Cooper, D.L.; Pham, H.; Powers, J.; Lee, W.C.; Wisniewski, T. Understanding the experience of caring for children with haemophilia: Cross-sectional study of caregivers in the United States. Haemophilia 2014, 20, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoefman, R.J.; van Exel, J.; Rose, J.M.; van de Wetering, E.J.; Brouwer, W.B. A discrete choice experiment to obtain a tariff for valuing informal care situations measured with the CarerQol instrument. Med. Decis. Making 2014, 34, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rand, S.; Malley, J.; Vadean, F.; Forder, J. Measuring the outcomes of long-term care for unpaid carers: Comparing the ASCOT-Carer, Carer Experience Scale and EQ-5D-3 L. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Meca, J.; Marín-Martínez, F.; López-López, J.A.; Núñez-Núñez, R.M.; Rubio-Aparicio, M.; López-García, J.J.; López-Pina, J.A.; Blázquez-Rincón, D.M.; López-Ibáñez, C.; López-Nicolás, R. Improving the reporting quality of reliability generalization meta-analyses: The REGEMA checklist. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 516–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefman, R.; Al-Janabi, H.; McCaffrey, N.; Currow, D.; Ratcliffe, J. Measuring caregiver outcomes in palliative care: A construct validation study of two instruments for use in economic evaluations. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1255–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, D.G. Sample size requirements for testing and estimating coefficient alpha. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2002, 27, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Meca, J.; López-López, J.A.; López-Pina, J.A. Some recommended statistical analytic practices when reliability generalization studies are conducted. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2013, 66, 402–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, J.; Knapp, G. On tests of the overall treatment effect in meta-analysis with normally distributed responses. Stat. Med. 2001, 20, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulders-Manders, C.M.; Kanters, T.A.; van Daele, P.L.A.; Hoppenreijs, E.; Legger, G.E.; van Laar, J.A.M.; Simon, A.; Roijen, L.H.-V. Decreased quality of life and societal impact of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome treated with canakinumab: A questionnaire based cohort study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzelthin, S.F.; Verbakel, E.; Veenstra, M.Y.; van Exel, J.; Ambergen, A.W.; Kempen, G.I.J.M. Positive and negative outcomes of informal caregiving at home and in institutionalised long-term care: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donis, J.H. Tipos de diseños de los estudios clínicos y epidemiológicos. Av. Biomed. 2013, 2, 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Payakachat, N.; Tilford, J.M.; Brouwer, W.B.; van Exel, N.J.; Grosse, S.D. Measuring health and well-being effects in family caregivers of children with craniofacial malformations. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoefman, R.J.; van Exel, N.J.; Looren de Jong, S.; Redekop, W.K.; Brouwer, W.B. A new test of the construct validity of the CarerQol instrument: Measuring the impact of informal care giving. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefman, R.J.; van Exel, J.; Brouwer, W.B. Measuring the impact of caregiving on informal carers: A construct validation study of the CarerQol instrument. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richters, A.; Melis, R.J.; van Exel, N.J.; Olde Rikkert, M.G.; van der Marck, M.A. Perseverance time of informal caregivers for people with dementia: Construct validity, responsiveness and predictive validity. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2017, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McLoughlin, C.; Goranitis, I.; Al-Janabi, H. Validity and Responsiveness of Preference-Based Quality-of-Life Measures in Informal Carers: A Comparison of 5 Measures Across 4 Conditions. Value Health 2020, 23, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaffrey, N.; Bucholc, J.; Rand, S.; Hoefman, R.; Ugalde, A.; Muldowney, A.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Engel, L. Head-to-Head Comparison of the Psychometric Properties of 3 Carer-Related Preference-Based Instruments. Value Health 2020, 23, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voormolen, D.C.; van Exel, J.; Brouwer, W.; Sköldunger, A.; Gonçalves-Pereira, M.; Irving, K.; Bieber, A.; Selbaek, G.; Woods, B.; Zanetti, O.; et al. A validation study of the CarerQol instrument in informal caregivers of people with dementia from eight European countries. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baji, P.; Brouwer, W.B.F.; van Exel, J.; Golicki, D.; Rupel, V.P.; Zrubka, Z.; Gulácsi, L.; Brodszky, V.; Rencz, F.; Péntek, M. Validation of the Hungarian version of the CarerQol instrument in informal caregivers: Results from a cross-sectional survey among the general population in Hungary. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbakile-Mahlanza, L.; van der Ploeg, E.S.; Busija, L.; Camp, C.; Walker, H.; O’Connor, D.W. A cluster-randomized crossover trial of Montessori activities delivered by family carers to nursing home residents with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 32, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.Y.; Park, H.; Lee, J.; Shaharuddin, K.K.B.; Gan, C.H. Self-stigma and its associations with stress and quality of life among Malaysian parents of children with autism. Child Care Health Dev. 2020, 46, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, C.; George, S.; Somerville, R.; Linnane, B.; Fitzpatrick, P. Caregiver burden of parents of young children with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2018, 17, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanly, P.; Maguire, R.; Balfe, M.; Hyland, P.; Timmons, A.; O’sullivan, E.; Butow, P.; Sharp, L. Burden and happiness in head and neck cancer carers: The role of supportive care needs. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 4283–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Subendran, J.; Smith, M.L.; Widjaja, E.; PEPSQOL Study Team. Care-related quality of life in caregivers of children with drug-resistant epilepsy. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 2221–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karg, N.; Graessel, E.; Randzio, O.; Pendergrass, A. Dementia as a predictor of care-related quality of life in informal caregivers: A cross-sectional study to investigate differences in health-related outcomes between dementia and non-dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.A.; Martínez, Ó.; Amayra, I.; López-Paz, J.F.; Al-Rashaida, M.; Lázaro, E.; Caballero, P.; Pérez, M.; Berrocoso, S.; García, M.; et al. Diseases Costs and Impact of the Caring Role on Informal Carers of Children with Neuromuscular Disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vluggen, T.P.M.M.; van Haastregt, J.C.M.; Tan, F.E.; Verbunt, J.A.; van Heugten, C.M.; Schols, J.M.G.A. Effectiveness of an integrated multidisciplinary geriatric rehabilitation programme for older persons with stroke: A multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoefman, R.J.; van Exel, J.; Brouwer, W.B.F. Measuring Care-Related Quality of Life of Caregivers for Use in Economic Evaluations: CarerQol Tariffs for Australia, Germany, Sweden, UK, and US. Pharmacoeconomics 2017, 35, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baji, P.; Farkas, M.; Golicki, D.; Rupel, V.P.; Hoefman, R.; Brouwer, W.B.F.; van Exel, J.; Zrubka, Z.; Gulácsi, L.; Péntek, M. Development of population tariffs for the CarerQol instrument for Hungary, Poland and Slovenia: A discrete choice experiment study to measure the burden of informal caregiving. PharmacoEconomics 2020, 38, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachantoni, A.; Evandrou, M.; Falkingham, J.; Robards, J. Informal care, health and mortality. Maturitas 2013, 74, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Pino-Casado, R.; Priego-Cubero, E.; López-Martínez, C.; Orgeta, V. Subjective caregiver burden and anxiety in informal caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutomski, J.E.; van Exel, N.J.; Kempen, G.I.; van Charante, E.P.M.; Elzen, W.P.J.D.; Jansen, A.P.D.; Krabbe, P.F.M.; Steunenberg, B.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Rikkert, M.G.M.O.; et al. Validation of the Care-Related Quality of Life Instrument in different study settings: Findings from The Older Persons and Informal Caregivers Survey Minimum DataSet (TOPICS-MDS). Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, M.; Cooper, H.; Kline, R.B.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Nezu, A.M.; Rao, S.M. Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenes-Ribera, L.; Duro-García, C.; López-Ibáñez, C.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Sánchez-Meca, J. The Adult Prosocialness Behavior Scale: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2022, 47, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Aparicio, M.; Badenes-Ribera, L.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Fabris, M.A.; Longobardi, C. A reliability generalization meta-analysis of self-report measures of muscle dysmorphia. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, 27, e12303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.; Task Force on Statistical Inference; American Psychological Association; Science Directorate. Statistical methods in psychology journal: Guidelines and explanations. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaney, K. Validating Psychological Constructs, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Charter, R.A. A breakdown of reliability coefficients by test type and reliability method, and the clinical implications of low reliability. J. Gen. Psychol. 2003, 130, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revelle, W.; Condon, D.M. Reliability from α to ω: A tutorial. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 1395–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. Stability versus change, dependability versus error: Issues in the assessment of personality over time. J. Res. Pers. 2004, 38, 319–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabedo-Peris, J.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Merino-Soto, C.; Ortiz-Morán, M. Basic Empathy Scale: A Systematic Review and Reliability Generalization Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2021, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, J.A.; Marín-Martínez, F.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Van den Noortgate, W.; Viechtbauer, W. Estimation of the predictive power of the model in mixed-effects meta-regression: A simulation study. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2014, 67, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epner, D.E.; Baile, W.F. Patient-centered care: The key to cultural competence. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23 (Suppl. S3), 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangalila, R.F.; van den Bos, G.A.; Stam, H.J.; van Exel, N.J.; Brouwer, W.B.; Roebroeck, M.E. Subjective caregiver burden of parents of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyckt, L.; Löthman, A.; Jörgensen, L.; Rylander, A.; Koernig, T. Burden of informal caregiving to patients with psychoses: A descriptive and methodological study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2013, 59, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanters, T.A.; van der Ploeg, A.T.; Brouwer, W.B.; Hakkaart, L. The impact of informal care for patients with Pompe disease: An application of the CarerQol instrument. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 2013, 110, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoefman, R.; Payakachat, N.; van Exel, J.; Kuhlthau, K.; Kovacs, E.; Pyne, J.; Tilford, J.M. Caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder and parents’ quality of life: Application of the CarerQol. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 1933–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janse, B.; Huijsman, R.; de Kuyper, R.D.; Fabbricotti, I.N. The effects of an integrated care intervention for the frail elderly on informal caregivers: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraijo, H.; Brouwer, W.; de Leeuw, R.; Schrijvers, G.; van Exel, J. The perseverance time of informal carers of dementia patients: Validation of a new measure to initiate transition of care at home to nursing home care. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014, 40, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlthau, K.; Payakachat, N.; Delahaye, J.; Hurson, J.; Pyne, J.M.; Kovacs, E.; Tilford, J.M. Quality of life for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr. Disord. 2014, 8, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-García, S.; Sánchez-Martínez, F.I.; Abellán-Perpiñán, J.M.; van Exel, J. Monetary valuation of informal care based on carers’ and noncarers’ preferences. Value Health 2015, 18, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilford, J.M.; Payakachat, N.; Kuhlthau, K.A.; Pyne, J.M.; Kovacs, E.; Bellando, J.; Williams, D.K.; Brouwer, W.B.; Frye, R.E. Treatment for sleep problems in children with autism and caregiver spillover effects. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 3613–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenkamp, M.; Hagedoorn, M.; Slaets, J.; Stolk, R.; Wittek, R.; Smidt, N. Subjective burden among spousal and adult-child informal caregivers of older adults: Results from a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, D.; Parkin, J.; Whitworth, V.; Rex, S.; Young, T.; Hampson, L.; Sheehan, J.; Maguire, C.; Cantrill, H.; Scott, E.; et al. Aquatic therapy for boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD): An external pilot randomized controlled trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2017, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E.P.; de Vugt, M.; Köhler, S.; Wolfs, C.; Kerpershoek, L.; Handels, R.L.; Orrell, M.; Woods, B.; Jelley, H.; Stephan, A.; et al. Caregiver profiles in dementia related to quality of life, depression and perseverance time in the European Actifcare study: The importance of social health. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenkamp, M.; Hagedoorn, M.; Wittek, R.; Stolk, R.; Smidt, N. The impact of older persons’ frailty on the care-related quality of life of their informal caregiver over time: Results from the TOPICS-MDS project. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 2705–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stjernswärd, S.; Hansson, L. Outcome of a web-based mindfulness intervention for families living with mental illness—A feasibility study. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2017, 42, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dam, P.H.; Achterberg, W.P.; Caljouw, M.A. Care-related quality of life of informal caregivers after geriatric rehabilitation. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Ree, C.; Ploegsma, K.; Kanters, T.A.; Roukema, J.A.; De Jongh, M.; Gosens, T. Care-related quality of life of informal caregivers of the elderly after a hip fracture. J. Patient Rep. Outcomes 2017, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handels, R.; Sköldunger, A.; Bieber, A.; Edwards, R.T.; Gonçalves-Pereira, M.; Hopper, L.; Irving, K.; Jelley, H.; Kerpershoek, L.; Marques, M.J.; et al. Quality of life, care resource use, and costs of dementia in 8 European countries in a cross-sectional cohort of the Actifcare study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 66, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerpershoek, L.; de Vugt, M.; Wolfs, C.; Woods, B.; Jelley, H.; Orrell, M.; Woods, B.; Jelley, H.; Orrell, M.; Stephan, A.; et al. Needs and quality of life of people with middle-stage dementia and their family carers from the European Actifcare study. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baji, P.; Golicki, D.; Prevolnik-Rupel, V.; Brouwer, W.B.; Zrubka, Z.; Gulácsi, L.; Péntek, M. The burden of informal caregiving in Hungary, Poland and Slovenia: Results from national representative surveys. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2019, 20, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, O.D.; Davies, B.M.; Kotter, M.R. Quality of life among informal caregivers of patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy: Cross-sectional questionnaire study. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2019, 8, e12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Naskar, N.N.; Basu, K.; Dasgupta, A.; Basu, R.; Paul, B. Care-Related Quality of Life of Caregivers of Beta-Thalassemia Major Children: An Epidemiological Study in Eastern India. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges-Machado, F.; Barros, D.; Ribeiro, Ó.; Carvalho, J. The Effects of COVID-19 Home Confinement in Dementia Care: Physical and Cognitive Decline, Severe Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and Increased Caregiving Burden. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dementiasr. 2020, 35, 1533317520976720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, L.; Rand, S.; Hoefman, R.; Bucholc, J.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Muldowney, A.; Ugalde, A.; McCaffrey, N. Measuring Carer Outcomes in an Economic Evaluation: A Content Comparison of the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit for Carers, Carer Experience Scale, and Care-Related Quality of Life Using Exploratory Factor Analysis. Med. Decis. Mak. 2020, 40, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifer, S.J.; Ho, K.A.; Lybrand, S.; Axford, L.J.; Roach, S. Alignment of preferences in the treatment of multiple myeloma—A discrete choice experiment of patient, carer, physician, and nurse preferences. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanters, T.A.; Brugts, J.J.; Manintveld, O.C.; Versteegh, M.M. Burden of Providing Informal Care for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Value Health 2020, 24, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Hoopen, L.W.; de Nijs, P.; Duvekot, J.; Greaves-Lord, K.; Hillegers, M.; Brouwer, W.; Hakkaart-van Roijen, L. Children with an Autism Spectrum Disorder and Their Caregivers: Capturing Health-Related and Care-Related Quality of Life. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfrink, T.R.; Ullrich, C.; Kunz, M.; Zuidema, S.U.; Westerhof, G.J. The Online Life Story Book: A Randomized Controlled Trial on the Effects of a Digital Reminiscence Intervention for People with (Very) Mild Dementia and Their Informal Caregivers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massé García, M.C. La Mujer y el Cuidado de la Vida. Comprensión Histórica y Perspectivas de Futuro. Cuad. Bioet. 2017, 28, 291–301. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cejalvo, E.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Gisbert-Pérez, J.; Badenes-Ribera, L. The CarerQol Instrument: A Systematic Review, Validity Analysis, and Generalization Reliability Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14061916

Cejalvo E, Martí-Vilar M, Gisbert-Pérez J, Badenes-Ribera L. The CarerQol Instrument: A Systematic Review, Validity Analysis, and Generalization Reliability Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(6):1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14061916

Chicago/Turabian StyleCejalvo, Elena, Manuel Martí-Vilar, Júlia Gisbert-Pérez, and Laura Badenes-Ribera. 2025. "The CarerQol Instrument: A Systematic Review, Validity Analysis, and Generalization Reliability Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 6: 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14061916

APA StyleCejalvo, E., Martí-Vilar, M., Gisbert-Pérez, J., & Badenes-Ribera, L. (2025). The CarerQol Instrument: A Systematic Review, Validity Analysis, and Generalization Reliability Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(6), 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14061916