Mechanical Protective Ventilation: New Paradigms in Thoracic Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

- “The non-dependent lung is not ventilated, as the perfusion persists; so that the whole perfusion to this lung adds to intrapulmonary shunt, leading to hypoxemia”.

- ○

- The “hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction” (HPV) should be protected

- ○

- FiO2 should be switched to 1.0 routinely

- ○

- The tidal volume of two lungs should be given to “one” (dependent) lung

- ○

- No PEEP to the dependent lung, as the increased pressure can divert the perfusion to non-ventilated lung.

- Most importantly, it has been realized that increased shunt is only one of the factors causing hypoxemia. Very probably, the suboptimal position of the airway device (e.g., double-lumen tube, which was placed only with auscultation) is the most possible (or common) reason of hypoxemia, as it has been reported that the routine use of fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB) was associated with the decrease in the incidence of hypoxemia from 25% to 5% [5]. Another possible reason is the ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch within the ventilated lung, i.e., “upper” parts of the ventilated lung are ventilated better, as the perfusion is still better in the lower parts. This means the possible reasons of hypoxemia during OLV are (not exclusively): malposition of airway device, increased shunt (non-ventilated lung is still perfused), and V/Q mismatch within the ventilated lung. As the historical approach has focused only on shunt, recent strategies suggest to use FOB (to prevent malposition) and different ventilation techniques to decrease the V/Q mismatch.

- It is not only the increased use of FOB but also advancements in anesthetic and surgical techniques and drugs that have played a role in the decrease in the frequency of hypoxemia. Yet, it has to be underlined that it is still an important challenge. Therefore, an anesthetist has to be familiar with the theory of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV):

- HPV (the name is self-explaining) denotes the physiological phenomenon whereby pulmonary arterioles undergo constriction in response to alveolar hypoxia, and it mitigates V/Q mismatch. It is characterized by a biphasic nature. Initially, there is a rapid onset within 100 msec, reaching a steady state within approximately 5–20 min. Subsequently, if alveolar hypoxemia persists, a more pronounced phase emerges around the 40th minute and a steady state within 60–120 min. If the second phase ensues, the HPV response persists for an extended duration. The most potent response occurs when approximately 20–40% of lung volume experiences an alveolar partial pressure of oxygen (PAO2) around 65–70 mmHg [6,7]. Volatile anesthetic agents impair HPV in a dose-dependent manner, but “modern” volatile anesthetics in their routine doses, with or without the combination of thoracic epidural anesthesia do not lead to a clinically relevant change in oxygenation [8].

- The switch of FiO2 to 1.0 is a rational instinct, only as a first step approach to “treat” the hypoxemia [9,10]; in other words, FiO2 of 1.0 makes sense if hypoxemia occurs, but the routine change at the initiation of OLV can be even harmful: First of all, this approach is irrational, if we assume that shunt leads to hypoxemia: “Hypoxemia as a result of increased shunt does not response to increase in FiO2”. One of the underestimated causes of hypoxemia during OLV is the V-Q mismatch (not shunt) within the dependent (ventilated) lung, and this is the part that benefits from the increase in FiO2. Another drawback of high FiO2 is the possibility of an “absorption atelectasis”, which is a more possible case in lateral decubitus position and the additional increase in pressure around the ventilated lung. Especially if no PEEP is applied as the historical guidelines suggest, the resulting atelectasis can worsen the hypoxemia. Furthermore, the lungs are highly vulnerable to oxygen toxicity due to their consistently high PO2, and hyperoxia elevates reactive oxygen species production, exceeding antioxidant capacity and leading to oxidative stress and potential tissue damage.

- About “high tidal volume and no PEEP”, it is now well known that the possible hazards overcome the benefits; not only regarding the PPC’s (which will be discussed in the next paragraphs) but also hypoxemia.

The Relative New Paradigm: Dealing with Lung Injury

- The “sick” lung is more prone to injury,

- The duration of ventilation is longer than healthy lungs,

- Only a very small part of the lung is ventilated: the so-called “baby lung” of Gattinoni. Unfortunately, this “healthy” area is becoming more vulnerable to injury, as it receives the whole tidal volume [18].

2. Protective Ventilation Strategies

2.1. Tidal Volume

2.2. Alveolar Recruitment Maneuver

2.3. Pressures

2.3.1. Driving Pressure

2.3.2. Positive End-Expiratory Pressure

2.4. “Open Lung Approach” (OLA)

3. Future Directions and Clinical Implications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Durkin, C.; Romano, K.; Egan, S.; Lohser, J. Hypoxemia During One-Lung Ventilation: Does It Really Matter? Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2021, 11, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentürk, M. New concepts of the management of one-lung ventilation. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2006, 19, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şentürk, M.; Slinger, P.; Cohen, E. Intraoperative mechanical ventilation strategies for one-lung ventilation. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2015, 29, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrando, C.; Carramiñana, A.; Piñeiro, P.; Mirabella, L.; Spadaro, S.; Librero, J.; Ramasco, F.; Scaramuzzo, G.; Cervantes, O.; Garutti, I.; et al. Individualised, perioperative open-lung ventilation strategy during one-lung ventilation (iPROVE-OLV): A multicentre, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karzai, W.; Schwarzkopf, K. Hypoxemia during one-lung ventilation: Prediction, prevention, and treatment. Anesthesiology 2009, 110, 1402–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licker, M.; Hagerman, A.; Jeleff, A.; Schorer, R.; Ellenberger, C. The hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: From physiology to clinical application in thoracic surgery. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2021, 15, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumb, A.B.; Slinger, P. Hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction: Physiology and anesthetic implications. Anesthesiology 2015, 122, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, P.E.; Sentürk, M.; Sungur Ulke, Z.; Toker, A.; Dilege, S.; Ozden, E.; Camci, E. Effects of thoracic epidural anaesthesia on pulmonary venous admixture and oxygenation during one-lung ventilation. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2007, 51, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozé, H.; Lafargue, M.; Batoz, H.; Picat, M.Q.; Perez, P.; Ouattara, A.; Janvier, G. Pressure-controlled ventilation and intrabronchial pressure during one-lung ventilation. Br. J. Anaesth. 2010, 105, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozé, H.; Lafargue, M.; Ouattara, A. Case scenario: Management of intraoperative hypoxemia during one-lung ventilation. Anesthesiology 2011, 114, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, R.S.; Colquhoun, D.A.; Durieux, M.E.; Kozower, B.D.; McMurry, T.L.; Bender, S.P.; Naik, B.I. Management of One-lung Ventilation: Impact of Tidal Volume on Complications after Thoracic Surgery. Anesthesiology 2016, 124, 1286–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceppa, D.P.; Kosinski, A.S.; Berry, M.F.; Tong, B.C.; Harpole, D.H.; Mitchell, J.D.; D’Amico, T.A.; Onaitis, M.W. Thoracoscopic lobectomy has increasing benefit in patients with poor pulmonary function: A Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database analysis. Ann. Surg. 2012, 256, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, R.; Xiang, W.; Ning, D.; Li, Z. Systematic review and meta-analysis on perioperative intervention to prevent postoperative atelectasis complications after thoracic surgery. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 10726–10734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlig, C.; Neto, A.S.; van der Woude, M.; Kiss, T.; Wittenstein, J.; Shelley, B.; Scholes, H.; Hiesmayr, M.; Vidal Melo, M.F.; Sances, D.; et al. Intraoperative mechanical ventilation practice in thoracic surgery patients and its association with postoperative pulmonary complications: Results of a multicenter prospective observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020, 20, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, H.C. A preliminary report on the 1952 epidemic of poliomyelitis in Copenhagen with special reference to the treatment of acute respiratory insufficiency. Lancet 1953, 261, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slutsky, A.S.; Ranieri, V.M. Ventilator-induced lung injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2126–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattinoni, L.; Tonetti, T.; Cressoni, M.; Cadringher, P.; Herrmann, P.; Moerer, O.; Protti, A.; Gotti, M.; Chiurazzi, C.; Carlesso, E.; et al. Ventilator-related causes of lung injury: The mechanical power. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, L.; Pesenti, A. The concept of “baby lung”. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.B.; Amato, M.B.P.; Hedenstierna, G. The Increasing Call for Protective Ventilation During Anesthesia. JAMA Surg. 2017, 152, 893–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, B.; Slinger, P. Lung protective strategies in anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2010, 105 (Suppl. 1), i108–i116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumello, D.; Coppola, S.; Froio, S. Toward lung protective ventilation during general anesthesia: A new challenge. Rev. Esp. Anestesiol. Reanim. 2013, 60, 549–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.k.; Mai, D.H.; Le, A.N.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Nguyen, C.T.; Vu, T.A. A review of intraoperative lung-protective mechanical ventilation strategy. Trends Anaesth. Crit. Care 2021, 37, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Ahn, H.J.; Kim, J.A.; Yang, M.; Heo, B.Y.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, Y.R.; Lee, S.H.; Jeong, H.; Choi, S.J.; et al. Driving Pressure during Thoracic Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesthesiology 2019, 130, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Ahn, H.J.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.A.; Yi, C.A.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, H.J. Does a protective ventilation strategy reduce the risk of pulmonary complications after lung cancer surgery?: A randomized controlled trial. Chest 2011, 139, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, C.; Mugarra, A.; Gutierrez, A.; Carbonell, J.A.; García, M.; Soro, M.; Tusman, G.; Belda, F.J. Setting individualized positive end-expiratory pressure level with a positive end-expiratory pressure decrement trial after a recruitment maneuver improves oxygenation and lung mechanics during one-lung ventilation. Anesth. Analg. 2014, 118, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, H.H.; Hedley-Whyte, J.; Laver, M.B. Impaired Oxygenation in Surgical Patients during General Anesthesia with Controlled Ventilation. A Concept of Atelectasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1963, 269, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.B.; Meade, M.O.; Slutsky, A.S.; Brochard, L.; Costa, E.L.; Schoenfeld, D.A.; Stewart, T.E.; Briel, M.; Talmor, D.; Mercat, A.; et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, R.G.; Matthay, M.A.; Morris, A.; Schoenfeld, D.; Thompson, B.T.; Wheeler, A. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treschan, T.A.; Kaisers, W.; Schaefer, M.S.; Bastin, B.; Schmalz, U.; Wania, V.; Eisenberger, C.F.; Saleh, A.; Weiss, M.; Schmitz, A.; et al. Ventilation with low tidal volumes during upper abdominal surgery does not improve postoperative lung function. Br. J. Anaesth. 2012, 109, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.-H.; Yoon, S.; Choe, H.W.; Seo, J.-H.; Bahk, J.-H. An optimal protective ventilation strategy in lung resection surgery: A prospective, single- center, 3-arm randomized controlled trial. Res. Sq. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, J.K.; Funk, D.J.; Slinger, P.; Srinathan, S.; Kidane, B. Tidal volume during 1-lung ventilation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 163, 1573–1585.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenstierna, G.; Tenling, A. The lung during and after thoracic anaesthesia. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2005, 18, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoftman, N.; Canales, C.; Leduc, M.; Mahajan, A. Positive end expiratory pressure during one-lung ventilation: Selecting ideal patients and ventilator settings with the aim of improving arterial oxygenation. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2011, 14, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozé, H.; Lafargue, M.; Perez, P.; Tafer, N.; Batoz, H.; Germain, C.; Janvier, G.; Ouattara, A. Reducing tidal volume and increasing positive end-expiratory pressure with constant plateau pressure during one-lung ventilation: Effect on oxygenation. Br. J. Anaesth. 2012, 108, 1022–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Yoon, S.; Nam, J.S.; Ahn, H.J.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, H.; Kim, H.K.; Blank, R.S.; Yun, S.C.; et al. Driving pressure-guided ventilation and postoperative pulmonary complications in thoracic surgery: A multicentre randomised clinical trial. Br. J. Anaesth. 2023, 130, e106–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidane, B.; Palma, D.C.; Badner, N.H.; Hamilton, M.; Leydier, L.; Fortin, D.; Inculet, R.I.; Malthaner, R.A. The Potential Dangers of Recruitment Maneuvers During One Lung Ventilation Surgery. J. Surg. Res. 2019, 234, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Jeon, Y.T.; Hwang, J.W.; Do, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, H.P. A preemptive alveolar recruitment strategy before one-lung ventilation improves arterial oxygenation in patients undergoing thoracic surgery: A prospective randomised study. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2011, 28, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, J.K.; Funk, D.J.; Slinger, P.; Srinathan, S.; Kidane, B. Positive end-expiratory pressure and recruitment maneuvers during one-lung ventilation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 160, 1112–1122.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, T.; Wittenstein, J.; Becker, C.; Birr, K.; Cinnella, G.; Cohen, E.; El Tahan, M.R.; Falcão, L.F.; Gregoretti, C.; Granell, M.; et al. Protective ventilation with high versus low positive end-expiratory pressure during one-lung ventilation for thoracic surgery (PROTHOR): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2019, 20, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, C.; Papazian, L.; Reignier, J.; Ayzac, L.; Loundou, A.; Forel, J.M. Effect of driving pressure on mortality in ARDS patients during lung protective mechanical ventilation in two randomized controlled trials. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.J.; Park, M.; Kim, J.A.; Yang, M.; Yoon, S.; Kim, B.R.; Bahk, J.H.; Oh, Y.J.; Lee, E.H. Driving pressure guided ventilation. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2020, 73, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.S.; Hemmes, S.N.; Barbas, C.S.; Beiderlinden, M.; Fernandez-Bustamante, A.; Futier, E.; Gajic, O.; El-Tahan, M.R.; Ghamdi, A.A.; Günay, E.; et al. Association between driving pressure and development of postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation for general anaesthesia: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caironi, P. Driving pressure and intraoperative protective ventilation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Yuan, S.; Yi, C.; Long, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Z. Titration of extra-PEEP against intrinsic-PEEP in severe asthma by electrical impedance tomography: A case report and literature review. Medicine 2020, 99, e20891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yueyi, J.; Jing, T.; Lianbing, G. A structured narrative review of clinical and experimental studies of the use of different positive end-expiratory pressure levels during thoracic surgery. Clin. Respir. J. 2022, 16, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohser, J.; Slinger, P. Lung Injury After One-Lung Ventilation: A Review of the Pathophysiologic Mechanisms Affecting the Ventilated and the Collapsed Lung. Anesth. Analg. 2015, 121, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santa Cruz, R.; Villarejo, F.; Irrazabal, C.; Ciapponi, A. High versus low positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) levels for mechanically ventilated adult patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021, Cd009098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, R.A.; van Kaam, A.H.; Haitsma, J.J.; Lachmann, B. High positive end-expiratory pressure levels promote bacterial translocation in experimental pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2007, 33, 1800–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rauseo, M.; Mirabella, L.; Grasso, S.; Cotoia, A.; Spadaro, S.; D’Antini, D.; Valentino, F.; Tullo, L.; Loizzi, D.; Sollitto, F.; et al. Peep titration based on the open lung approach during one lung ventilation in thoracic surgery: A physiological study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slinger, P.D.; Kruger, M.; McRae, K.; Winton, T. Relation of the static compliance curve and positive end-expiratory pressure to oxygenation during one-lung ventilation. Anesthesiology 2001, 95, 1096–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, L.; Caironi, P.; Cressoni, M.; Chiumello, D.; Ranieri, V.M.; Quintel, M.; Russo, S.; Patroniti, N.; Cornejo, R.; Bugedo, G. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 1775–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belda, J.; Ferrando, C.; Garutti, I. The Effects of an Open-Lung Approach During One-Lung Ventilation on Postoperative Pulmonary Complications and Driving Pressure: A Descriptive, Multicenter National Study. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2018, 32, 2665–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.-J.; Zhao, F.-Z.; Piccioni, F.; Shi, R.; Si, X.; Chen, S.; Cecconi, M.; Yin, H.-Y. Individualized PEEP titration by lung compliance during one-lung ventilation: A meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buggy, P.M.; Buggy, D.J. Individualised perioperative ventilation in one-lung anaesthesia? Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 182–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güldner, A.; Kiss, T.; Serpa Neto, A.; Hemmes, S.N.; Canet, J.; Spieth, P.M.; Rocco, P.R.; Schultz, M.J.; Pelosi, P.; Gama de Abreu, M. Intraoperative protective mechanical ventilation for prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications: A comprehensive review of the role of tidal volume, positive end-expiratory pressure, and lung recruitment maneuvers. Anesthesiology 2015, 123, 692–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaFollette, R.; Hojnowski, K.; Norton, J.; DiRocco, J.; Carney, D.; Nieman, G. Using pressure-volume curves to set proper PEEP in acute lung injury. Nurs. Crit. Care 2007, 12, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, L.; Collino, F.; Maiolo, G.; Rapetti, F.; Romitti, F.; Tonetti, T.; Vasques, F.; Quintel, M. Positive end-expiratory pressure: How to set it at the individual level. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zersen, K.M. Setting the optimal positive end-expiratory pressure: A narrative review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1083290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Chi, Y.; Long, Y.; Yuan, S.; Frerichs, I.; Möller, K.; Fu, F.; Zhao, Z. Influence of overdistension/recruitment induced by high positive end-expiratory pressure on ventilation-perfusion matching assessed by electrical impedance tomography with saline bolus. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmali, D.; Sowho, M.; Bose, S.; Pearce, J.; Tejwani, V.; Diamant, Z.; Yarlagadda, K.; Ponce, E.; Eikelis, N.; Otvos, T.; et al. Functional imaging for assessing regional lung ventilation in preclinical and clinical research. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1160292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, M.; Roy Cardinal, M.H.; Chassé, M.; Garneau, S.; Cavayas, Y.A.; Cloutier, G.; Denault, A.Y. Regional pleural strain measurements during mechanical ventilation using ultrasound elastography: A randomized, crossover, proof of concept physiologic study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 935482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Components | Purpose | Related Problems and Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Low tidal volume (TV) |

|

|

| Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) |

|

|

| Low driving pressure (DP)(Plateau pressure minus PEEP) |

|

|

| Alveolar recruitment maneuver (ARM) |

|

|

| Low mechanical power (MP) |

|

|

| Method | Principle | Comment/Concern |

|---|---|---|

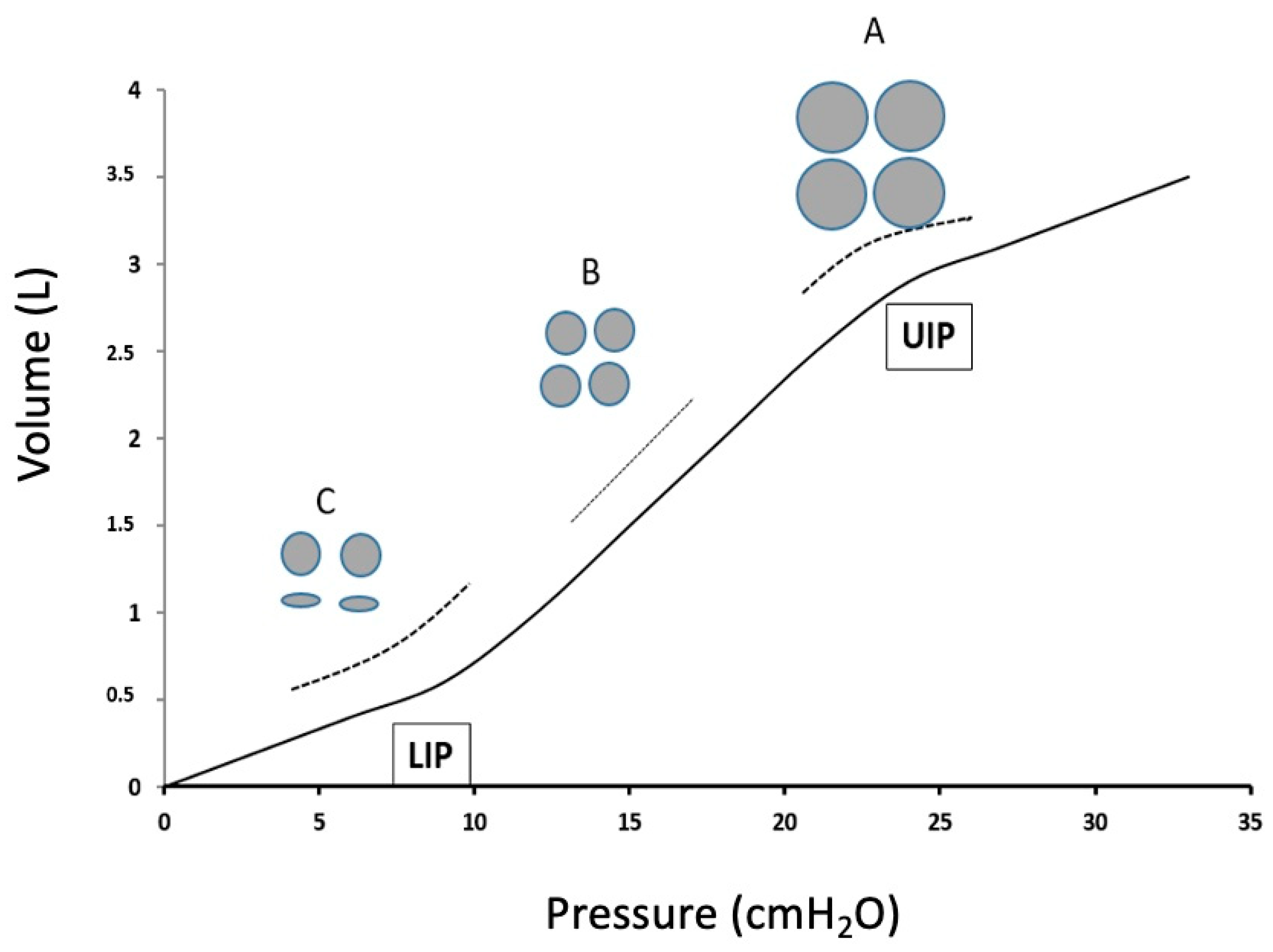

| Identification of LIP and UIP on the P-V curve | PEEP to achieve the highest static compliance (see also Figure 1) | Static compliance (i.e., no inspiratory flow) is difficult to measure in daily practice. Titrated PEEP does not eliminate that some (lower) areas remain atelectatic, as some (upper) areas are overinflated. |

| Electric impedance tomography (EIT) | Visual detection of atelectasis. PEEP to avoid atelectasis. | Difficult in OR, esp. in thoracic patients. |

| Lung ultrasound | Visual detection of atelectasis | Less difficult than EIT, but still difficult during the operation. Subjective evaluation possible |

| Ventilatory stress index | Analysis of the slope of the pressure-time curve during VCV: PEEP to achieve a linear slope (not concave or convex) | Although being a very appropriate method, and easy at the same time, it is not used often in daily practice. |

| Transpulmonary pressure | Oesophageal pressure as the surrogate. The most direct way to measure the stress and strain | Specific motors necessary. Artifacts possible. |

| Mechanical power | Measurement takes the RR and PEEP also in account | Relative new method. Almost no experience for PEEP titration in OR. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Canbaz, M.; Şentürk, E.; Şentürk, M. Mechanical Protective Ventilation: New Paradigms in Thoracic Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051674

Canbaz M, Şentürk E, Şentürk M. Mechanical Protective Ventilation: New Paradigms in Thoracic Surgery. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(5):1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051674

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanbaz, Mert, Emre Şentürk, and Mert Şentürk. 2025. "Mechanical Protective Ventilation: New Paradigms in Thoracic Surgery" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 5: 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051674

APA StyleCanbaz, M., Şentürk, E., & Şentürk, M. (2025). Mechanical Protective Ventilation: New Paradigms in Thoracic Surgery. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(5), 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14051674