The Impact of Surgical Repair on Restlessness in Infants with Non-Incarcerated Inguinal Hernias: A Prospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Ethical Aspects

2.3. Study Outcomes

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlations Between the Different Restlessness Scores

3.2. Comparison to Control

3.3. Comparison of Hernia Patients Before and After Hernia Repair

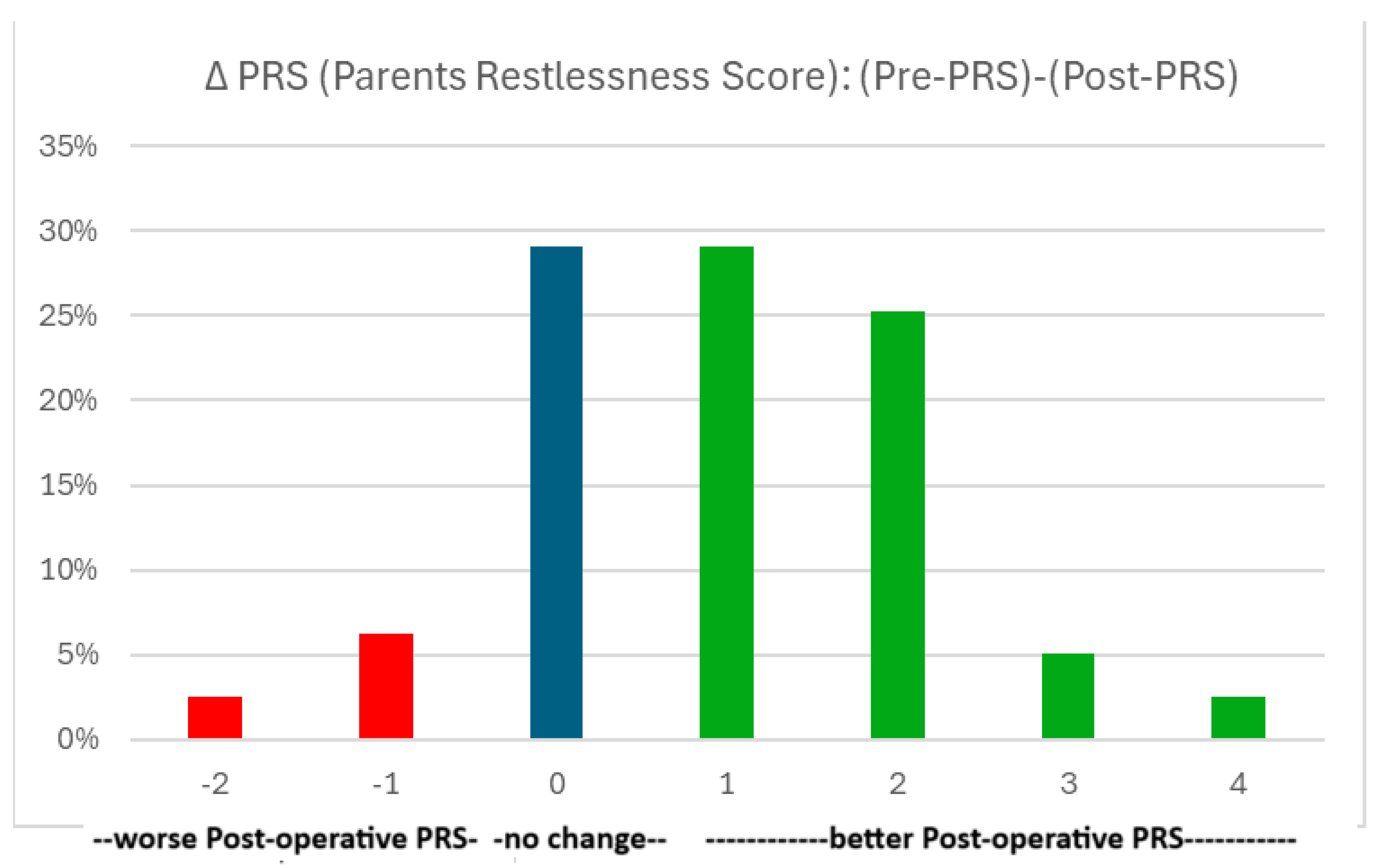

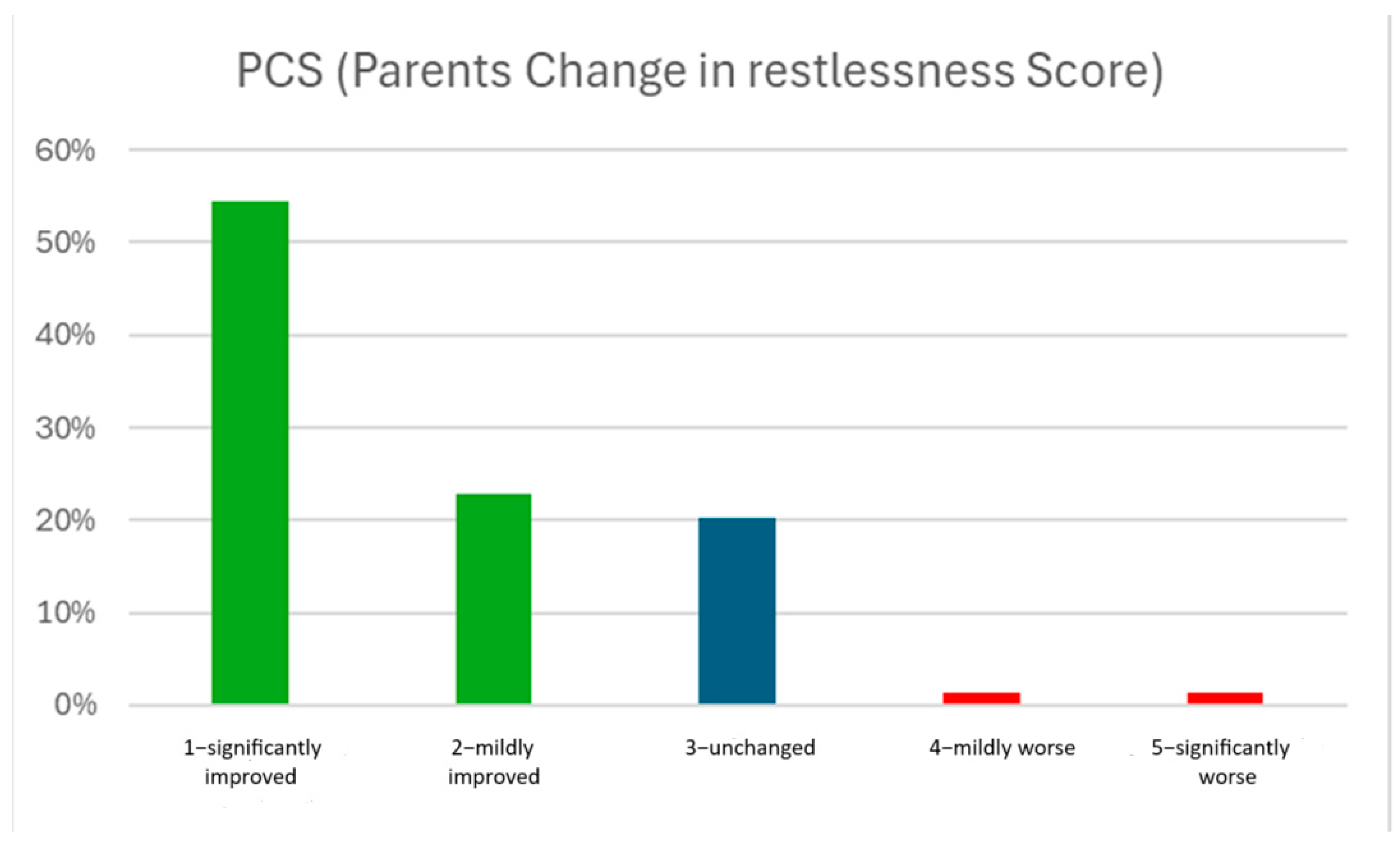

3.4. Association of Patient Factors with Restlessness

3.5. Sub-Analysis of Patients with Pre-PRS ≥ 3 (N = 52)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ED | Emergency Department |

| IBQ | Infant Behavioral Questionnaire |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| PCS | Parents’ Change in restlessness Score |

| POD | Post-Operative Day |

| PRS | Parents’ Restlessness Score |

References

- Ismail, J.; Nallasamy, K. Crying Infant. Indian J. Pediatr. 2017, 84, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trocinski, D.R.; Pearigen, P.D. The crying infant. Emerg. Med. Clin. North. Am. 1998, 16, 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, O.B.; Fitzgibbons, R.J., Jr.; Cusick, R.A. Pediatric inguinal hernias, hydroceles, and undescended testicles. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 92, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ein, S.H.; Njere, I.; Ein, A. Six thousand three hundred sixty-one pediatric inguinal hernias: A 35-year review. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2006, 41, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Zivin, S.; Panchal, N.; Wilbur, A.; Bresler, M. Sonography of female genital hernias presenting as labia majora masses. J. Ultrasound Med. 2014, 33, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogorelić, Z.; Anand, S.; Križanac, Z.; Singh, A. Comparison of Recurrence and Complication Rates Following Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair among Preterm versus Full-Term Newborns: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children 2021, 8, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M.K. Measurement of temperament in infancy. Child. Dev. 1981, 52, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeap, E.; Pacilli, M.; Nataraja, R.M. Inguinal hernias in children. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 49, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsnorth, A.; LeBlanc, K. Hernias: Inguinal and incisional. Lancet 2003, 362, 1561–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, J.M.; O’Brien, M.; Beasley, S.W.; Teague, W.J.; King, S.K. Jones’ Clinical Paediatric Surgery, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2015; p. 332. [Google Scholar]

- HerniaSurge Group. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 2018, 22, 1–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbons, R.J., Jr.; Ramanan, B.; Arya, S.; Turner, S.A.; Li, X.; Gibbs, J.O.; Reda, D.J.; Investigators of the Original Trial. Long-term results of a randomized controlled trial of a nonoperative strategy (watchful waiting) for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berndsen, M.R.; Gudbjartsson, T.; Berndsen, F.H. Inguinal hernia—Review. Laeknabladid 2019, 105, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Dop, L.M.; Van Egmond, S.; Heijne, J.; van Rosmalen, J.; de Goede, B.; Wijsmuller, A.R.; Kleinrensink, G.J.; Tanis, P.J.; Jeekel, J.; Lange, J.F.; et al. Twelve-year outcomes of watchful waiting versus surgery of mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic inguinal hernia in men aged 50 years and older: A randomised controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 64, 102207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, L.; Norrie, J.; O’Dwyer, P.J. Long-term follow-up of patients with a painless inguinal hernia from a randomized clinical trial. Br. J. Surg. 2011, 98, 596–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosquet, E.M.; White, M.T.; Hails, K.; Cabrera, I.; Wright, R.J. The Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised: Factor structure in a culturally and sociodemographically diverse sample in the United States. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2016, 43, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhai, S.A.; Glenn, I.C.; Ponsky, T.A. Incarcerated Pediatric Hernias. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 97, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkura, T.; Kumori, K.; Kawamura, T.; Manako, J.; Ishibashi, S.; Funabashi, N.; Tajima, Y. Association of pediatric inguinal hernia contents with patient age and sex. Pediatr. Int. 2022, 64, e15193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreuning, K.M.; Barendsen, R.W.; van Trotsenburg, A.P.; Twisk, J.W.; Sleeboom, C.; van Heurn, L.E.; Derikx, J.P. Inguinal hernia in girls: A retrospective analysis of over 1000 patients. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 1908–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, T.; Ueno, S.; Hirakawa, H.; Tei, E.; Mori, M. Surgical Treatment of Inguinal Hernia with Prolapsed Ovary in Young Girls: Emergency Surgery or Elective Surgery. Tokai J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2017, 42, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, C.; Gargiulo, F.; Farina, A.; Del Conte, F.; Cortese, G.; Servillo, G.; Escolino, M. Laparoscopic Treatment of Inguinal Ovarian Hernia in Female Infants and Children: Standardizing the Technique. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2019, 29, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Parrish, M.; Vargas Chaves, D.P.; Taylor, K.; Achuff, B.J.; Lasa, J.J.; Hopper, A.; Ramamoorthy, C. Analgesia, Sedation, and Anesthesia for Neonates With Cardiac Disease. Pediatrics 2022, 150 (Suppl. 2), e2022056415K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagno, E.; Fabiano, G.; Carmellino, V.; Cerchio, R.; De, B.; Lauria, B.; Mercurio, G.; Coscia, A.; Ponte, G.; Bondone, C. Neonatal pain assessment scales: Review of the literature. Prof. Inferm. 2022, 75, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mencía, S.; Alonso, C.; Pallás-Alonso, C.; López-Herce, J. Maternal And Child Health And Development Network Ii Samid Ii. Evaluation and Treatment of Pain in Fetuses, Neonates and Children. Children 2022, 9, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.J.; Kwon, H.; Ha, S.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, D.Y.; Namgoong, J.M.; Nam, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Jung, E.; Cho, M.J. Optimal timing for inguinal hernia repair in premature infants: Surgical issues for inguinal hernia in premature infants. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2023, 104, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, M.A.; Neal, D.; Pairawan, S.; Tagge, E.P.; Hashmi, A.; Islam, S.; Khan, F.A. Optimal Timing of Inguinal Hernia Repair in Premature Infants: A NSQIP-P Study. J. Surg. Res. 2023, 283, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamakhshary, M.; To, T.; Guan, J.; Langer, J.C. Risk of incarceration of inguinal hernia among infants and young children awaiting elective surgery. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2008, 179, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hernia N = 76 | Control N = 76 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| male:female | 55:21 | 55:21 | NA |

| term:preterm | 53:23 | 53:23 | NA |

| Corrected age in months (median and IQR) | 2.6 (1.6–4.2) | 2.8 (1.7–4.6) | 0.98 |

| PRS (median and IQR) | Pre: 3 (2–4) | 2 (2–2) | <0.001 |

| Post: 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–2) | 0.5 | |

| IBQ (median and IQR) | Pre: 3.2 (2.3–4.1) | 3.1 (2.3–4.1) | 0.28 |

| Post: 2.9 (1.7–3.7) | 3.1 (2.3–4.1) | 0.1 |

| Patient Characteristics | Pre-PRS | Post-PRS | ΔPRS | PCS | ΔIBQ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | p | Median (IQR) | p | Median (IQR) | p | Median (IQR) | p | Median (IQR) | p | |

| male:female | 3 (2–4):3 (1.75–3) | 0.094 | 2 (1–3):1 (1–2) | 0.04 | 1 (0–2):1.5 (0–2) | 0.51 | 1 (1–2.5):1 (1–2) | 0.31 | 0.25 (−0.46–1.23):0.49 (−0.26–0.87) | 0.86 |

| preterm:term | 3.2 ± 1.2:2.8 ± 1.2 | 0.07 | 1.8 ± 0.9:2 ± 0.9 | 0.36 | 1.4 ± 1.4:0.7 ± 1.1 | 0.03 | 1.7 ± 0.9:1.7 ± 0.9 | 0.92 | 1.7 ± 1.3:1.7 ± 0.9 | 0.27 |

| unilat:bilat | 3 (2–3.25):3 (3–4.5) | 0.13 | 2 (1–3):2 (1–3) | 0.83 | 1 (0–2):2 (0.5–2) | 0.06 | 1 (1–2.25):1 (1–2) | 0.49 | 0.27 (−0.29–1.14):0.36 (−0.94–1.08) | 0.71 |

| no ED:yes ED | 3 (2–3):3 (3–4) | 0.03 | 2 (1–3):2 (1–2) | 0.25 | 0 (0–1):1.5 (1–2) | <0.001 | 2 (1–3):1 (1–2) | 0.03 | 0.12 (−0.5–1):0.7 (0.02–1.45) | 0.03 |

| reducible:non-reducible (females) | 3 (1.5–3.5):2 (1.5–3) | 0.51 | 1 (1–2):1 (1–2) | 0.69 | 2 (0–2):1 (0–2) | 0.56 | 1 (1–2.5):1 (1–2) | 0.95 | 0.12 (−0.25–0.83):0.62 (−0.27–0.87) | 0.69 |

| Correlation coefficient | p | Correlation coefficient | p | Correlation coefficient | p | Correlation coefficient | p | Correlation coefficient | p | |

| Corrected age, months | −0.23 | 0.04 | −0.14 | 0.23 | −0.14 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.46 | −0.11 | 0.33 |

| Time post-op | −0.03 | 0.82 | −0.19 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.25 | −0.0 | 0.99 |

| Pre-PRS | 1.00 | NA | 0.36 | <0.001 | 0.67 | <0.001 | −0.37 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schaffer, O.; Blich, O.; Yulevich, A.; Niazov, E.; Armon, Y.; Zmora, O. The Impact of Surgical Repair on Restlessness in Infants with Non-Incarcerated Inguinal Hernias: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041105

Schaffer O, Blich O, Yulevich A, Niazov E, Armon Y, Zmora O. The Impact of Surgical Repair on Restlessness in Infants with Non-Incarcerated Inguinal Hernias: A Prospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(4):1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041105

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchaffer, Ortal, Ori Blich, Alon Yulevich, Eleonora Niazov, Yaron Armon, and Osnat Zmora. 2025. "The Impact of Surgical Repair on Restlessness in Infants with Non-Incarcerated Inguinal Hernias: A Prospective Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 4: 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041105

APA StyleSchaffer, O., Blich, O., Yulevich, A., Niazov, E., Armon, Y., & Zmora, O. (2025). The Impact of Surgical Repair on Restlessness in Infants with Non-Incarcerated Inguinal Hernias: A Prospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(4), 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041105