Laparoscopic Hysteropexy: How, When and for Whom Is It an Alternative Option? A Narrative Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

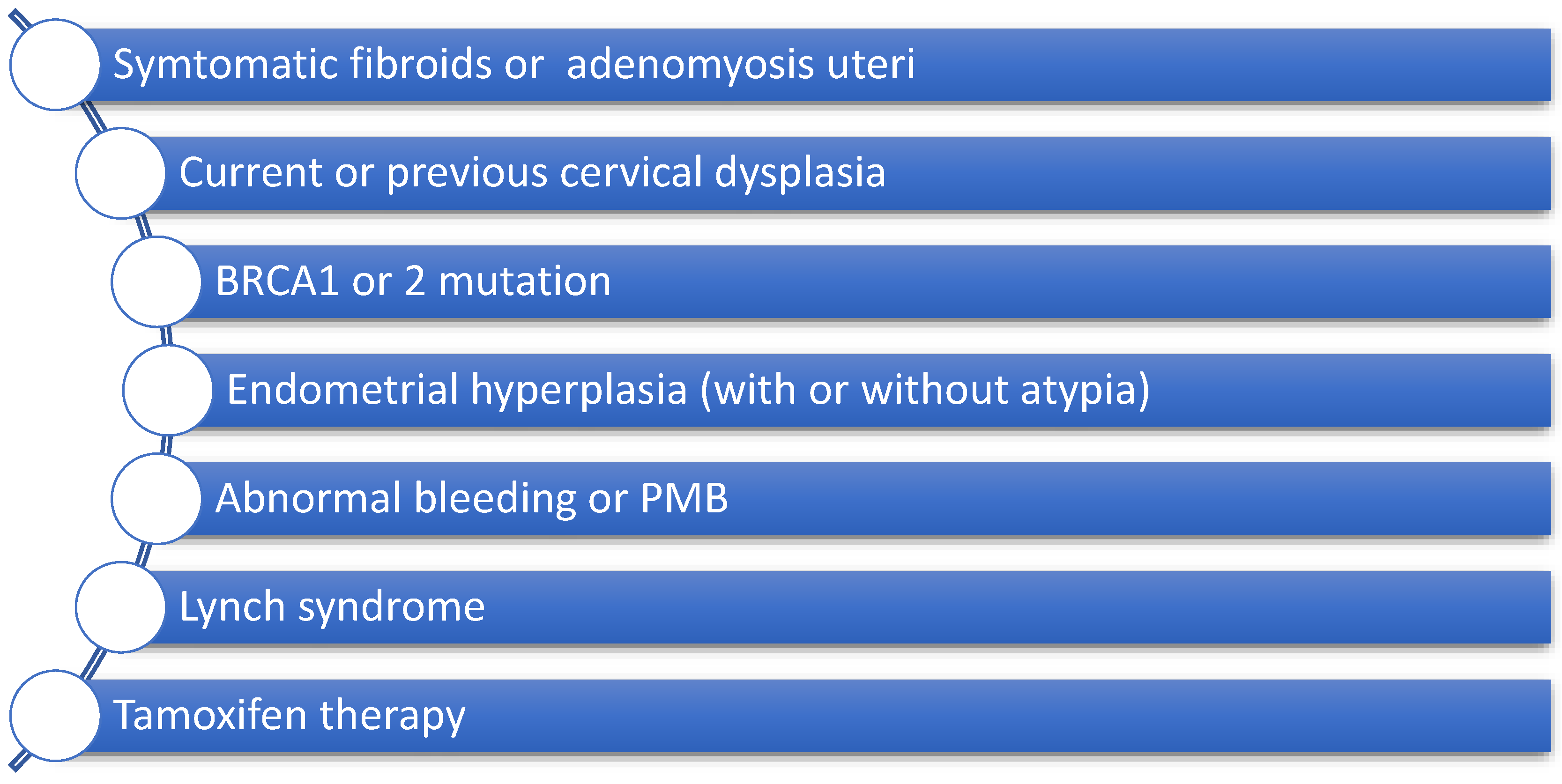

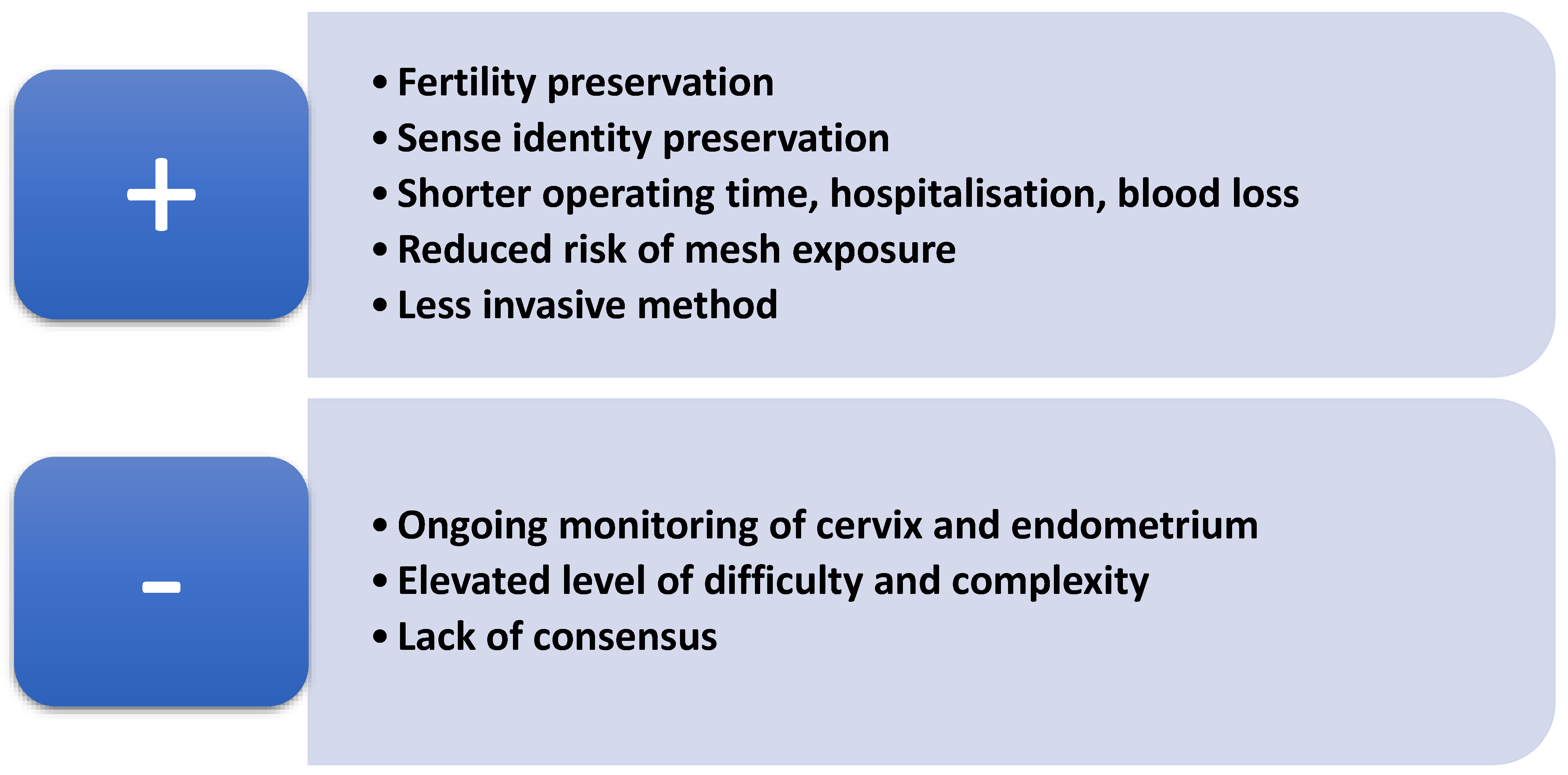

2. How to Identify a Suitable Patient for Uterine Preservation

3. Available Techniques of Laparoscopic Hysteropexy

3.1. Laparoscopic Sacral Hysteropexy (LSHP)

3.2. Laparoscopic Uterosacral Hysteropexy (LUSH)

3.3. Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension (LLS)

3.4. Laparoscopic Hysteropectopexy (LP)

4. Comparison of Transvaginal and Laparoscopic Approach

5. Pregnancy Outcomes After Hysteropexy

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haylen, B.T.; Maher, C.F.; Barber, M.D.; Camargo, S.; Dandolu, V.; Digesu, A.; Goldman, H.B.; Huser, M.; Milani, A.L.; Moran, P.A.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) Joint Report on the Terminology for Female Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 27, 165–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, A.Y.; Glinter, H.; Marcus-Braun, N. Narrative Review of the Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Pathophysiology of Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2020, 46, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonney, V. The Principles That Should Underlie All Operations for Prolapse. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1934, 41, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchionni, M.; Bracco, G.L.; Checcucci, V.; Carabaneanu, A.; Coccia, E.M.; Mecacci, F.; Scarselli, G. True Incidence of Vaginal Vault Prolapse. Thirteen Years of Experience. J. Reprod. Med. 1999, 44, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rahmanou, P.; White, B.; Price, N.; Jackson, S. Laparoscopic Hysteropexy: 1- to 4-Year Follow-Up of Women Postoperatively. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2014, 25, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, A.C.; Barber, M.D.; Paraiso, M.F.R.; Ridgeway, B.; Jelovsek, J.E.; Walters, M.D. Attitudes Toward Hysterectomy in Women Undergoing Evaluation for Uterovaginal Prolapse. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 19, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korbly, N.B.; Kassis, N.C.; Good, M.M.; Richardson, M.L.; Book, N.M.; Yip, S.; Saguan, D.; Gross, C.; Evans, J.; Lopes, V.V.; et al. Patient Preferences for Uterine Preservation and Hysterectomy in Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 209, 470.e1–470.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, N.; Slack, A.; Jackson, S. Laparoscopic Hysteropexy: The Initial Results of a Uterine Suspension Procedure for Uterovaginal Prolapse. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2010, 117, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgeway, B.M. Does Prolapse Equal Hysterectomy? The Role of Uterine Conservation in Women with Uterovaginal Prolapse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutman, R.E. Does the Uterus Need to Be Removed to Correct Uterovaginal Prolapse? Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 28, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kow, N.; Goldman, H.B.; Ridgeway, B. Management Options for Women with Uterine Prolapse Interested in Uterine Preservation. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2013, 14, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.H.; Lee, S.B.; Na, E.D.; Kim, H.C. Correlation Between Obesity and Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Korean Women. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2020, 63, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, C.L.; Stram, D.O.; Ness, R.B.; Stram, D.A.; Roman, L.D.; Templeman, C.; Lee, A.W.; Menon, U.; Fasching, P.A.; McAlpine, J.N.; et al. Population Distribution of Lifetime Risk of Ovarian Cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2015, 24, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, A.C.; Walters, M.D.; Larkin, K.S.; Barber, M.D. Risk of Unanticipated Abnormal Gynecologic Pathology at the Time of Hysterectomy for Uterovaginal Prolapse. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 507.e1–507.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Lynch, L.; Eiriksson, L. Information Needs of Lynch Syndrome and BRCA 1/2 Mutation Carriers Considering Risk-Reducing Gynecological Surgery: A Qualitative Study of the Decision-Making Process. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2024, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neis, K.; Zubke, W.; Römer, T.; Schwerdtfeger, K.; Schollmeyer, T.; Rimbach, S.; Holthaus, B.; Solomayer, E.; Bojahr, B.; Neis, F.; et al. Indications and Route of Hysterectomy for Benign Diseases. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S3 Level, AWMF Registry No. 015/070, April 2015). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2016, 76, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Su, T.-H.; Wang, Y.-L.; Lee, M.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Wang, K.-G.; Chen, G.-D. Risk Factors for Failure of Transvaginal Sacrospinous Uterine Suspension in the Treatment of Uterovaginal Prolapse. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2005, 104, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, S.A.; Fonseca, M.C.M.; Bortolini, M.A.T.; Girão, M.J.B.C.; Roque, M.T.; Castro, R.A. Hysteropreservation Versus Hysterectomy in the Surgical Treatment of Uterine Prolapse: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 1617–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriwether, K.V.; Balk, E.M.; Antosh, D.D.; Olivera, C.K.; Kim-Fine, S.; Murphy, M.; Grimes, C.L.; Sleemi, A.; Singh, R.; Dieter, A.A.; et al. Uterine-Preserving Surgeries for the Repair of Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis and Clinical Practice Guidelines. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2019, 30, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, C.M.; Sadler, L.; Harvey, S.A.; Stewart, A.W. The Association of Hysterectomy and Menopause: A Prospective Cohort Study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2005, 112, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, V.; Rajkumari, S.; Walia, G.K.; Devi, N.K.; Saraswathy, K.N. Menopausal Symptoms Among Women with and Without Hysterectomy. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2023, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, R.; Maher, C. Uterine-Preserving POP Surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2013, 24, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Jeon, M.J. How and on Whom to Perform Uterine-Preserving Surgery for Uterine Prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2022, 65, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexhepi, S.; Rexhepi, E.; Stumm, M.; Mallmann, P.; Ludwig, S. Laparoscopic Bilateral Cervicosacropexy and Vaginosacropexy: New Surgical Treatment Option in Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Urinary Incontinence. J. Endourol. 2018, 32, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanou, P.; Price, N.; Jackson, S. Laparoscopic Hysteropexy: A Novel Technique for Uterine Preservation Surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2014, 25, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferis, H.; Price, N.; Jackson, S. Laparoscopic Hysteropexy: 10 Years’ Experience. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, H.; Otsuka, S.; Abe, H.; Tsukada, S. Comparison of Outcomes of Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy with Concomitant Supracervical Hysterectomy or Uterine Preservation. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023, 34, 2217–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, G.; Vacca, L.; Panico, G.; Rumolo, V.; Caramazza, D.; Lombisani, A.; Rossitto, C.; Gadonneix, P.; Scambia, G.; Ercoli, A. Laparoscopic Sacral Hysteropexy Versus Laparoscopic Sacral Colpopexy plus Supracervical Hysterectomy in Patients with Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022, 33, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Cao, L.; Ryan, N.A.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H. Laparoscopic Sacral Hysteropexy Versus Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy with Hysterectomy for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 27, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tius, V.; Arcieri, M.; Taliento, C.; Pellecchia, G.; Capobianco, G.; Simoncini, T.; Panico, G.; Caramazza, D.; Campagna, G.; Driul, L.; et al. Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy with Concurrent Hysterectomy or Uterine Preservation: A Metanalysis and Systematic Review. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2025, 168, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupelian, A.S.; Vashisht, A.; Sambandan, N.; Cutner, A. Laparoscopic Wrap Round Mesh Sacrohysteropexy for the Management of Apical Prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 27, 1889–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Api, M.; Kayatas, S.; Boza, A.; Nazik, H.; Aytan, H. Laparoscopic Sacral Uteropexy with Cravat Technique—Experience and Results. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2014, 40, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourik, S.L.; Martens, J.E.; Aktas, M. Uterine Preservation in Pelvic Organ Prolapse Using Robot Assisted Laparoscopic Sacrohysteropexy: Quality of Life and Technique. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 165, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, M.; Perelló, M.; Bataller, E.; Espuña, M.; Parellada, M.; Genís, D.; Balasch, J.; Carmona, F. Comparison between Laparoscopic Sacral Hysteropexy and Subtotal Hysterectomy plus Cervicopexy in Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Pilot Study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2015, 34, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C. Laparoscopic Suture Hysteropexy for Uterine Prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 97, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uccella, S.; Ghezzi, F.; Bergamini, V.; Serati, M.; Cromi, A.; Franchi, M.; Bolis, P. Laparoscopic Uterosacral Ligaments Plication for the Treatment of Uterine Prolapse. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2007, 276, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, C.; Takacs, P. Laparoscopic Uterosacral Uterine Suspension: A Minimally Invasive Technique for Treating Pelvic Organ Prolapse. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2006, 13, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, N.D.; Seman, E.I.; O’Shea, R.T.; Keirse, M.J.N.C. Effect of Uterine Preservation on Outcome of Laparoscopic Uterosacral Suspension. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2013, 20, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Yahya, R.; Chill, H.H.; Levin, G.; Reuveni-Salzman, A.; Shveiky, D. Laparoscopic Uterosacral Ligament Hysteropexy vs. Total Vaginal Hysterectomy with Uterosacral Ligament Suspension for Anterior and Apical Prolapse: Surgical Outcome and Patient Satisfaction. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, R.; Nikolopoulos, K.I.; Claydon, L.S. Clinical Outcomes in Women Undergoing Laparoscopic Hysteropexy: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 208, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuisson, J.B.; Chapron, C. Laparoscopic Iliac Colpo-Uterine Suspension for the Treatment of Genital Prolapse Using Two Meshes: A New Operative Laparoscopic Approach. J. Gynecol. Surg. 1998, 14, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapandji, M. Treatment of Urogenital Prolapse by Colpo-Isthmo-Cystopexy with Transverse Strip and Crossed, Multiple Layer, Ligamento-Peritoneal Douglasorrhaphy. Ann. Chir. 1967, 21, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Dubuisson, J.-B.; Yaron, M.; Wenger, J.-M.; Jacob, S. Treatment of Genital Prolapse by Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension Using Mesh: A Series of 73 Patients. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2008, 15, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksin, Ş.; Andan, C. Postoperative Results of Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension Operation: A Clinical Trials Study. Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1069110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumbasar, S.; Salman, S.; Sogut, O.; Ketenci Gencer, F.; Bacak, H.B.; Tezcan, A.D.; Timur, G.Y. Uterine-Sparing Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension in the Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, O.; Yassa, M.; Eren, E.; Birol İlter, P.; Tuğ, N. A Randomized, Prospective, Controlled Study Comparing Uterine Preserving Laparoscopic Lateral Suspension with Mesh Versus Laparoscopic Sacrohysteropexy in the Treatment of Uterine Prolapse. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 297, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, C.; Noé, K.G. Laparoscopic Pectopexy: A New Technique of Prolapse Surgery for Obese Patients. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 284, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noé, G.K.; Schiermeier, S.; Papathemelis, T.; Fuellers, U.; Khudyakov, A.; Altmann, H.-H.; Borowski, S.; Morawski, P.P.; Gantert, M.; De Vree, B.; et al. Prospective International Multicenter Pectopexy Trial: Interim Results and Findings Post Surgery. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 244, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noé, G.K.; Barnard, A.; Schiermeier, S.; Anapolski, M. Current Role of Hysterectomy in Pelvic Floor Surgery: Time for Reappraisal? A Review of Current Literature and Expert Discussion. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9934486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.N.; Yim, M.H.; Na, Y.J.; Song, Y.J.; Kim, H.G. Comparison of Laparoscopic Hysteropectopexy and Vaginal Hysterectomy in Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 76, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, A.; Esin, S.; Guven, S.; Salman, C.; Ozyuncu, O. The Manchester Operation for Uterine Prolapse. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2006, 92, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.G.; Brodman, M.L.; Dottino, P.R.; Bodian, C.; Friedman, F.; Bogursky, E. Manchester Procedure vs. Vaginal Hysterectomy for Uterine Prolapse. A Comparison. J. Reprod. Med. 1995, 40, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.F.P. Surgical Treatment for Uterine Prolapse in Young Women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1966, 95, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, R.H.; Atkin, P.F. Uterine Disease after the Manchester Repair Operation. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1970, 77, 852–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucchi, A.; Lazzeri, M.; Porena, M.; Mearini, L.; Costantini, E. Uterus Preservation in Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2010, 7, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, T.A.; Milani, A.L.; Kluivers, K.B.; Withagen, M.I.J.; Vierhout, M.E. The Effectiveness of Surgical Correction of Uterine Prolapse: Cervical Amputation with Uterosacral Ligament Plication (Modified Manchester) Versus Vaginal Hysterectomy with High Uterosacral Ligament Plication. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2009, 20, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karram, M.M.; Walters, M.D. Clinical Urogynecology; Mosby Inc.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, C.; Feiner, B.; Baessler, K.; Schmid, C. Surgical Management of Pelvic Organ Prolapse in Women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 30, CD004014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefni, M.; El-Toukhy, T.; Bhaumik, J.; Katsimanis, E. Sacrospinous Cervicocolpopexy with Uterine Conservation for Uterovaginal Prolapse in Elderly Women: An Evolving Concept. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 188, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Brummen, H.J.; van de Pol, G.; Aalders, C.I.M.; Heintz, A.P.M.; van der Vaart, C.H. Sacrospinous Hysteropexy Compared to Vaginal Hysterectomy as Primary Surgical Treatment for a Descensus Uteri: Effects on Urinary Symptoms. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2003, 14, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oudheusden, A.M.J.; Coolen, A.-L.W.M.; Hoskam, H.; Veen, J.; Bongers, M.Y. Laparoscopic Sacrohysteropexy Versus Vaginal Sacrospinous Hysteropexy as Treatment for Uterine Descent: Comparison of Long-Term Outcomes. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023, 34, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van IJsselmuiden, M.; van Oudheusden, A.; Veen, J.; van de Pol, G.; Vollebregt, A.; Radder, C.; Housmans, S.; van Kuijk, S.; Deprest, J.; Bongers, M.; et al. Hysteropexy in the Treatment of Uterine Prolapse Stage 2 or Higher: Laparoscopic Sacrohysteropexy Versus Sacrospinous Hysteropexy—A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial (LAVA Trial). BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 127, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haya, N.; Baessler, K.; Christmann-Schmid, C.; de Tayrac, R.; Dietz, V.; Guldberg, R.; Mascarenhas, T.; Nussler, E.; Ballard, E.; Ankardal, M.; et al. Prolapse and Continence Surgery in Countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in 2012. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212, 755.e1–755.e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewski, M.; Kołodyńska, G.; Mucha, A.; Bełza, Ł.; Nowak, K.; Andrzejewski, W. The Assessment of Quality of Life and Satisfaction with Life of Patients Before and After Surgery of an Isolated Apical Defect Using Synthetic Materials. BMC Urol. 2020, 20, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letouzey, V.; Ulrich, D.; Balenbois, E.; Cornille, A.; de Tayrac, R.; Fatton, B. Utero-Vaginal Suspension Using Bilateral Vaginal Anterior Sacrospinous Fixation with Mesh: Intermediate Results of a Cohort Study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2015, 26, 1803–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, R.E.; Rardin, C.R.; Sokol, E.R.; Matthews, C.; Park, A.J.; Iglesia, C.B.; Geoffrion, R.; Sokol, A.I.; Karram, M.; Cundiff, G.W.; et al. Vaginal and Laparoscopic Mesh Hysteropexy for Uterovaginal Prolapse: A Parallel Cohort Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 216, 38.e1–38.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J.J.; Sokol, E.R.; Rardin, C.R.; Cundiff, G.W.; Paraiso, M.F.R.; Chou, J.; Gutman, R.E. Long-Term Outcomes After Vaginal and Laparoscopic Mesh Hysteropexy for Uterovaginal Prolapse: A Parallel Cohort Study (EVAULT). Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 28, e215–e221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seracchioli, R.; Hourcabie, J.-A.; Vianello, F.; Govoni, F.; Pollastri, P.; Venturoli, S. Laparoscopic Treatment of Pelvic Floor Defects in Women of Reproductive Age. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 2004, 11, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferis, H.; Price, N.; Jackson, S. Pregnancy Following Laparoscopic Hysteropexy—A Case Series. Gynecol. Surg. 2017, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pitsillidi, A.; Noé, G.K. Laparoscopic Hysteropexy: How, When and for Whom Is It an Alternative Option? A Narrative Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041080

Pitsillidi A, Noé GK. Laparoscopic Hysteropexy: How, When and for Whom Is It an Alternative Option? A Narrative Review of the Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(4):1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041080

Chicago/Turabian StylePitsillidi, Anna, and Günter Karl Noé. 2025. "Laparoscopic Hysteropexy: How, When and for Whom Is It an Alternative Option? A Narrative Review of the Literature" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 4: 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041080

APA StylePitsillidi, A., & Noé, G. K. (2025). Laparoscopic Hysteropexy: How, When and for Whom Is It an Alternative Option? A Narrative Review of the Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(4), 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041080