Risk Stratification Tools in Acute Heart Failure and Their Roles in Personalized Follow-Up

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Tools for Prognostic Risk Stratification

2.1. Assessment of Residual Congestion

- Clinical signs and symptoms have low sensitivity for detecting residual or subclinical congestion. To enhance diagnostic accuracy, several clinical scores have been developed, though these are not routinely implemented in everyday clinical practice [12].

- Lung ultrasound (LUS) evaluates pulmonary congestion through quantification of comet-tail artifacts (B-lines): the number of B-lines correlates directly with congestion severity and is associated with a poorer prognosis. In a meta-analysis of 13 studies on acute HF, the presence of more than 15 B-lines at discharge was associated with a five-fold increased risk of rehospitalization and death [14]. In outpatient settings, having more than 3 B-lines identified patients at a four-fold increased risk [15].

- Inferior vena cava (IVC) ultrasound can evaluate persistent subclinical venous congestion through measurements of IVC diameter and its respiratory variation (optimal threshold values: ≤21 mm diameter with >50% collapsibility). For a more comprehensive assessment, a multiorgan ultrasound approach known as venous extended ultrasound (VExUS) has been proposed, which includes evaluation of the IVC, hepatic veins, portal vein, and renal vein [16].Further echocardiographic parameters to assess congestion include measurements of pulmonary and left ventricular filling pressures [17]. The presence of post-capillary or combined pre- and post-capillary pulmonary hypertension is associated with poor prognosis. Evaluation of right ventricular function also has prognostic value: specifically, the TAPSE/PASP ratio (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion/systolic pulmonary artery pressure), with a cut-off value of 0.36, serves as a negative outcome marker [18].Another critical component in the evaluation of congestion is the measurement of NPs, which will be discussed in the next section.

- Remote and home-based monitoring of congestion is also becoming increasingly feasible. Implantable devices equipped with multisensor software offer promising solutions. A systematic review and meta-analysis of eight randomized trials (4347 patients) demonstrated that these home-monitoring strategies are more effective than standard monitoring in reducing the composite endpoint of death and HF rehospitalization—primarily driven by reduced readmissions [19]. The CardioMEMS HF System, an implantable sensor placed in a branch of the left pulmonary artery, measures pulmonary pressure and transmits data to an external device for clinical review and remote management. A meta-analysis of three studies revealed a significant reduction in hospitalizations/urgent visits and all-cause mortality in HF patients associated with CardioMEMS use [20]. Nevertheless, patient selection criteria for this technology remain to be clearly defined.

2.2. Risk Stratification by Disease Stage

- I: inotropes;

- N: NYHA class III–IV or elevated natriuretic peptides;

- E: end-organ dysfunction;

- E: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shocks;

- D: decreased ejection fraction;

- H: hospitalization;

- E: edema or escalating diuretic requirement;

- L: low blood pressure;

- P: poor response to prognostic medical therapy.

2.3. Biomarkers

2.4. Assessment of Frailty and Comorbidities

2.5. From Traditional Scores to Artificial Intelligence

- Reflect a broad, real-world HF population;

- Include relevant comorbidities;

- Encompass the full spectrum of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF);

- Integrate NPs, functional status, and echocardiographic parameters;

- Be regularly updated to reflect evolving therapies;

- Be simple to use and widely adopted in clinical practice [50].

- The ability to handle complex, multidimensional interactions between variables;

- Personalized risk prediction rather than population-level estimations;

- Greater adaptability to diverse patient populations and contemporary cohorts;

- Potential for integration into electronic health records, thereby reducing clinician workload and enabling real-time decision support [55].

- Golas et al. applied an AI model to retrospective data from 11,000 patients and found it outperformed traditional models in predicting 30-day hospital readmissions [56].

- Kwon et al. developed an AI system that successfully predicted in-hospital, 12-month, and 36-month mortality, surpassing the predictive power of conventional scores such as MAGGIC [57].

- Shah et al. employed machine learning techniques to identify HFpEF phenotypes with significantly different risks of mortality and hospitalization, recognizing three distinct clusters with unique outcomes [58].

- Many AI models demonstrate only modest performance gains over traditional approaches;

- Data quality and consistency across diverse clinical settings is not always available, as datasets often vary in completeness, standardization, and representation;

- Classic issues such as missing data, limited generalizability, and competing risks persist;

- Most models rely on static data snapshots, whereas incorporating longitudinal trends could enhance predictive accuracy;

- The inclusion of a large number of variables can compromise clinical interpretability;

- Key prognostic data types—such as hemodynamic parameters, clinical narratives, imaging, and omics—are often underutilized in current AI applications

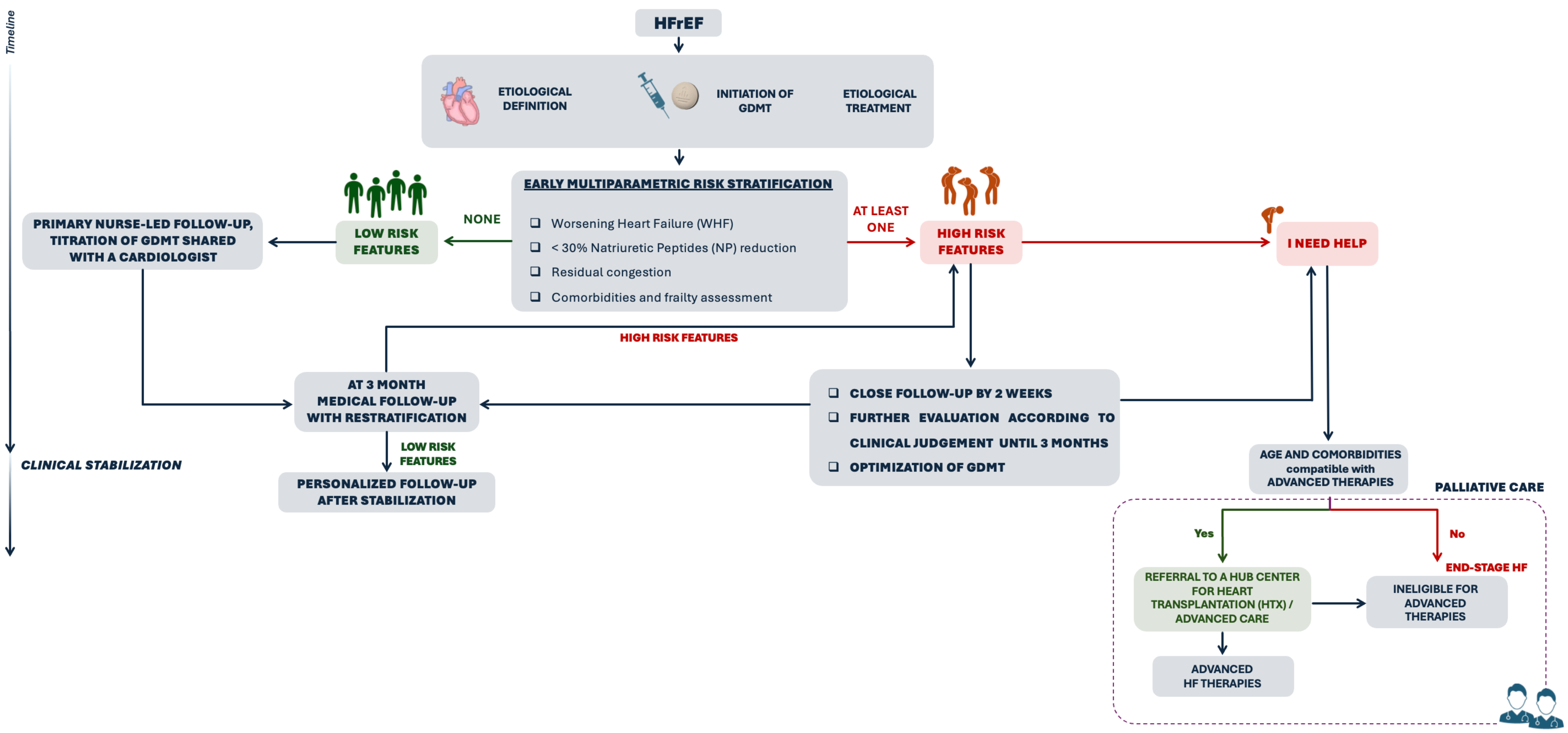

3. Tailored Follow-Up Strategies

- Biomarkers, particularly BNP/NT-proBNP;

- Clinical and echocardiographic assessment of residual congestion;

- Identification of clinical features indicative of AdvHF or WHF.

- (1)

- HFrEF

- Presence of AdHF or WHF criteria;

- Clinical, echocardiographic, or biomarker evidence of residual congestion;

- Inadequate reduction in NP levels during hospitalization;

- Presence of multiple comorbidities and frailty.

- (2)

- HFmrEF and HFpEF

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HF | Heart failure | |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction | |

| HFmrEF | Heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction | |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction | |

| GDMT | Guideline-directed medical therapy | |

| BBs | Beta-blockers | |

| ARNIs | Angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors | |

| ACEi/ARB | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers | |

| MRAs | Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | |

| SGLT2is | Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors | |

| WHF | Worsening Heart Failure | |

| AdvHF | Advanced Heart failure | |

| HHF | Hospitalization for Heart failure | |

| MDTs | Multidisciplinary teams | |

| LUS | Lung ultrasound | |

| IVC | Inferior vena cava | |

| VExUS | Venous extended ultrasound | |

| TAPSE/PASP | Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion/systolic pulmonary artery pressure | |

| NPs | Natriuretic peptides | |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association | |

| BNP | Brain Natriuretic Peptide | |

| DT | E-wave Deceleration Time | |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide | |

| sTDI | Right ventricle’s S wave Tissue Doppler Imaging velocity | |

| TDI | Tissue Doppler Imaging | |

| TRV | Tricuspid regurgitation velocity | |

| MAGGIC | Meta-Analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure score | |

| SHFM | Seattle Heart Failure Model | |

| MECKI | Metabolic Exercise Cardiac Kidney Index | |

| I-NEED-HELP | I = inotropes; N: NYHA class III–IV or elevated natriuretic peptides; E = end-organ dysfunction; E = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shocks; D = decreased ejection fraction; H = hospitalization; E = edema or escalating diuretic requirement; L = low blood pressure; P: poor response to prognostic medical therapy | |

| CPET | Cardiopulmonary exercise testing | |

| pVO2 | Peak oxygen consumption | |

| VE/VCO2 | Ventilatory efficiency slope | |

| 3C-HF | Cardiac and Comorbid Conditions Heart Failure | |

| HFFS | Heart Failure Frailty Score | |

| sHFFS | Simplified-Heart Failure Frailty Score | |

| AI | Artificial intelligence | |

References

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar]

- Chioncel, O.; Lainscak, M.; Seferovic, P.M.; Anker, S.D.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Harjola, V.P.; Parissis, J.; Laroche, C.; Piepoli, M.F.; Fonseca, C.; et al. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: An analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollenberg, S.M.; Stevenson, L.W.; Ahmad, T.; Butler, J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Givertz, M.M.; Katz, J.N.; Lindenfeld, J.; Metra, M.; Vaduganathan, M.; et al. 2024 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Clinical Assessment, Management, and Trajectory of Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure Focused Update. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 84, 1241–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, J.A.M.; López, J.A.C.; Mendoza, A.C.; González, A.M.; Alvarez, A.A.; Cruz, C.C.; Fernández, R.A.; Pacheco, P.J.; Ramírez, G.R.; Vargas, A.R.; et al. Vulnerable period in heart failure: A window of opportunity for the optimization of treatment—A statement by Mexican experts. Drugs Context. 2024, 13, 2023-8-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tano, G.; De Maria, R.; Gonzini, L.; Aspromonte, N.; Di Lenarda, A.; Feola, M.; Marini, M.; Milli, M.; Misuraca, G.; Mortara, A.; et al. The 30-day metric in acute heart failure revisited: Data from IN-HF Outcome, an Italian nationwide cardiology registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebazaa, A.; Davison, B.; Chioncel, O.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Diaz, R.; Filippatos, G.; Metra, M.; Pang, P.S.; Parsons, D.; Shlyakhto, E.; et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapies for acute heart failure (STRONG-HF): A multinational, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet 2022, 400, 1938–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, F.; Orso, F.; Colivicchi, F.; Magnani, G.; Piepoli, M.F.; Senni, M.; Di Lenarda, A.; De Maria, R.; Tarantini, L.; Corrà, U.; et al. Medical treatments in ambulatory heart failure patients: First data from the BRING-UP-3 Heart Failure Study. J. Card. Fail. 2025, 31, 1847–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, M.; Biegus, J.; Asakage, A.; Gayat, E.; Harjola, V.P.; Ishihara, S.; Lassus, J.; Liu, P.P.; Parissis, J.; Rossignol, P.; et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapies for acute heart failure in elderly patients: A sub-analysis of the STRONG-HF randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2023, 25, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicori, P.; Shah, P.; Cuthbert, J.; Urbinati, A.; Zhang, J.; Kallvikbacka-Bennett, A.; Clark, A.L.; Cleland, J.G.F. Prevalence, pattern and clinical relevance of ultrasound indices of congestion in outpatients with heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Gracia, J.; Demissei, B.G.; ter Maaten, J.M.; Cleland, J.G.F.; O’Connor, C.M.; Metra, M.; Düngen, H.D.; Cotter, G.; Davison, B.A.; Bloomfield, D.M.; et al. Prevalence, predictors and clinical outcome of residual congestion in acute decompensated heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 258, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girerd, N.; Seronde, M.F.; Coiro, S.; Chouihed, T.; Bilbault, P.; Braun, F.; Kenizou, D.; Maillier, B.; Nazeyrollas, P.; Roul, G.; et al. Integrative assessment of congestion in heart failure throughout the patient journey. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullens, W.; Damman, K.; Harjola, V.P.; Mebazaa, A.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Martens, P.; Testani, J.M.; Tang, W.H.W.; Orso, F.; Rossignol, P.; et al. The use of diuretics in heart failure with congestion—A position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargani, L.; Pang, P.S.; Frassi, F.; Miglioranza, M.H.; Dini, F.L.; Landi, P.; Picano, E. Persistent pulmonary congestion before discharge predicts rehospitalization in heart failure: A lung ultrasound study. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound 2015, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platz, E.; Merz, A.A.; Jhund, P.S.; Vazir, A.; Campbell, R.; McMurray, J.J.V. Dynamic changes and prognostic value of pulmonary congestion by lung ultrasound in acute and chronic heart failure: A systematic review. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stassen, J.; Falter, M.; Herbots, L.; Timmermans, P.; Dendale, P.; Verwerft, J. Assessment of venous congestion using vascular ultrasound. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Tomasoni, D.; Bayes-Genis, A.; de Boer, R.A.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Dargie, H.; Filippatos, G.; Gayat, E.; et al. Pre-discharge and early post-discharge management of patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: A scientific statement by the Heart Failure Association of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2023, 25, 1115–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guazzi, M.; Naeije, R. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure: Pathophysiology, pathobiology, and emerging clinical perspectives. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 1718–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, A.; Princi, G.; Romiti, G.F.; Prosperi, S.; Calvieri, C.; Musumeci, M.B.; Savo, A.; Piro, A.; Anzini, M.; Volpe, M.; et al. Device-based remote monitoring strategies for congestion-guided management of patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 2333–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermann, C.E.; Ertl, G. Remote heart failure management guided by pulmonary artery pressure home monitoring: Rewriting the future? Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3669–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, K.; Kok, W.E.; Eurlings, L.W.; van der Velde, E.T.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Samani, N.J.; de Boer, R.A.; Metra, M.; Agewall, S.; Dickstein, K.; et al. A novel discharge risk model for patients hospitalised for acute decompensated heart failure incorporating N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels: A European collaboration on acute decompensated heart failure: ÉLAN-HF score. Heart 2014, 100, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goonewardena, S.N.; Gemignani, A.; Ronan, A.; Qureshi, A.; Diffenbach, C.; Sharma, S.; Drazner, M.H.; Pellikka, P.A.; Abraham, T.P. Comparison of hand-carried ultrasound assessment of the inferior vena cava and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide for predicting readmission after hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2008, 1, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kociol, R.D.; Horton, J.R.; Fonarow, G.C.; Yancy, C.W.; Butler, J.; Hernandez, A.F.; Lee, K.L.; O’Connor, C.M.; Peacock, W.F.; Walsh, M.N.; et al. Admission, discharge, or change in B-type natriuretic peptide and long-term outcomes: Data from OPTIMIZE-HF linked to Medicare claims. Circ. Heart Fail. 2011, 4, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancellotti, P.; Galderisi, M.; Edvardsen, T.; Donal, E.; Voigt, J.U.; Neskovic, A.N.; Zamorano, J.L.; Cardim, N.; Popescu, B.A.; Marwick, T.H.; et al. Echo-Doppler estimation of left ventricular filling pressure: Results of the multicentre EACVI Euro-Filling study. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 18, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subías, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuade, C.N.; Mizus, M.; Wald, J.W.; Goldberg, L.R.; Jessup, M.; Umscheid, C.A. Brain-type natriuretic peptide and amino-terminal pro-brain-type natriuretic peptide discharge thresholds for acute decompensated heart failure: A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 166, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, A.; Abou Kamar, S.; Malgie, J.; Denaxas, S.; Hemingway, H.; Ariti, C.A.; Cowie, M.R.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Greene, S.J.; et al. The different risk of new-onset, chronic, worsening, and advanced heart failure: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, S.J.; Bauersachs, J.; Brugts, J.J.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Pieske, B.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Anker, S.D.; Voors, A.A.; Butler, J.; Ezekowitz, J.; et al. Management of worsening heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: JACC Focus Seminar 3/3. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, W.C.; Mozaffarian, D.; Linker, D.T.; Sutradhar, S.; Anker, S.D.; Cropp, A.; Anand, I.; Maggioni, A.; Burton, P.; Sullivan, M.; et al. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: Prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation 2006, 113, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwald, E. Chronic heart failure: A look through the rear view mirror. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 1391–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostoni, P.; Corrà, U.; Cattadori, G.; Veglia, F.; Battaia, E.; La Gioia, R.; Scardovi, A.B.; Sinagra, G.; Limongelli, G.; Metra, M.; et al. Metabolic exercise test data combined with cardiac and kidney indexes, the MECKI score: A multiparametric approach to heart failure prognosis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 2710–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnesi, M.; Ghiraldin, D.; Vizzardi, E.; Metra, M.; Tomasoni, D.; Aimo, A.; Passino, C.; Emdin, M.; Senni, M.; Lombardi, C.; et al. Detailed Assessment of the “i Need Help” Criteria in Patients with Heart Failure: Insights from the HELP-HF Registry. Circ. Heart Fail. 2023, 16, E011003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, R.; Bakken, K.; D’Elia, E.; Lewis, G.D. Mini-Focus Issue: Exercise and heart failure Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2016, 4, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritt, L.E.; Myers, J.; Stein, R.; Arena, R.; Guazzi, M.; Bensimhon, D.; Hansen, J.E.; Chase, P.; Forman, D.E.; Cahalin, L.P.; et al. Additive prognostic value of a cardiopulmonary exercise test score in patients with heart failure and intermediate risk. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 178, 262–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiglione, V.; Aimo, A.; Vergaro, G.; Saccaro, L.; Passino, C.; Emdin, M. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and management of heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G.; Musella, F.; D’Amore, C.; Vassallo, E.; Losco, T.; Gambardella, F.; Cecere, M.; Pagano, G.; Rengo, F.; Perrone-Filardi, P. Changes of natriuretic peptides predict hospital admissions in patients with chronic heart failure. A meta-analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2014, 2, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G.; Hage, C.; Orsini, N.; Vedin, O.; Cosentino, F.; Lund, L.H. Reductions in N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide Levels Are Associated with Lower Mortality and Heart Failure Hospitalization Rates in Patients with Heart Failure with Mid-Range and Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ. Heart Fail. 2016, 9, e003105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.; McDonald, K.; de Boer, R.A.; Maisel, A.; Cleland, J.G.; Kozhuharov, N.; Coats, A.J.S.; Metra, M.; Mebazaa, A.; Ruschitzka, F.; et al. Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology practical guidance on the use of natriuretic peptide concentrations. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felker, G.M.; Anstrom, K.J.; Adams, K.F.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Fiuzat, M.; Houston-Miller, N.; Januzzi, J.L.; Mark, D.B.; O’Connor, C.M.; Ahmad, T.; et al. Effect of natriuretic peptide–guided therapy on hospitalization or cardiovascular mortality in high-risk patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, C.; Berthelot, E.; Coats, A.J.S.; Lopatin, Y.; Piepoli, M.F.; Senni, M.; Filippatos, G.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Lam, C.S.P.; Chioncel, O.; et al. Assessment of frailty in patients with heart failure: A new Heart Failure Frailty Score developed by Delphi consensus. ESC Heart Fail. 2025, 12, 1818–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchmanowicz, I.; Lee, C.S.; Vitale, C.; Manulik, S.; Denfeld, Q.E.; Rosińczuk, J.; Drozd, M.; Jankowska-Polańska, B.; Coats, A.J.S.; Jaarsma, T.; et al. Frailty and the risk of all-cause mortality and hospitalization in chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 3427–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talha, K.M.; Pandey, A.; Fudim, M.; Butler, J.; Anker, S.D.; Khan, M.S. Frailty and heart failure: State-of-the-art review. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1959–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denfeld, Q.E.; Winters-Stone, K.; Mudd, J.O.; Gelow, J.M.; Kurdi, S.; Lee, C.S. The prevalence of frailty in heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 236, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denfeld, Q.E.; Turrise, S.; MacLaughlin, E.J.; Grady, K.L.; Davidson, P.M.; Lee, C.S.; Wu, J.R.; Redeker, N.S.; Sciacca, K.; Dekker, R.L.; et al. Preventing and Managing Falls in Adults with Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual Outcomes 2022, 15, E000108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denfeld, Q.E.; Jha, S.R.; Fung, E.; Kurmani, S.; Chien, C.V.; Davidson, P.M.; Metra, M.; Schulze, P.C.; Adigun, R.; Potena, L.; et al. Assessing and managing frailty in advanced heart failure: An International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation consensus statement. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2024, 43, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobashigawa, J.; Shah, P.; Joseph, S.; Mehra, M.; Deng, M.; Fairweather, D.; Patel, J.; Miller, L.; Zuckermann, A.; Rasmusson, K.; et al. Frailty in heart transplantation: Report from the heart workgroup of a consensus conference on frailty. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirkowski, K.; Vellone, E.; Żółkowska, B.; Cocchieri, A.; Candelieri, A.; Lee, C.S.; Riegel, B.; Jaarsma, T.; Uchmanowicz, I. Frailty and Heart Failure: Clinical Insights, Patient Outcomes and Future Directions. Card. Fail. Rev. 2025, 11, e05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulignano, G.; Del Sindaco, D.; Di Lenarda, A.; Tarantini, L.; Cioffi, G.; Gregori, D.; Tinti, M.D.; Sinagra, G.; Minardi, G.; Senni, M.; et al. Incremental Value of Gait Speed in Predicting Prognosis of Older Adults With Heart Failure: Insights From the IMAGE-HF Study. JACC Heart Fail. 2016, 4, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Park, D.I.; Lee, J.; Oh, O.; Kim, N.; Nam, G. Relationship between comorbidity and health outcomes in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrà, U.; Magini, A.; Paolillo, S.; Frigerio, M.; Giannuzzi, P.; Agostoni, P.; Cattadori, G.; Parati, G.; Piepoli, M.F. Comparison among different multiparametric scores for risk stratification in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepa, M.; Fonseca, C.; Chioncel, O.; Laroche, C.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Coats, A.J.S.; Miani, D.; Filippatos, G.; Ruschitzka, F.; Maggioni, A.P.; et al. Performance of prognostic risk scores in chronic heart failure patients enrolled in the European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codina, P.; Lupón, J.; Borrellas, A.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Santesmases, J.; Altimir, S.; González-Costello, J.; Rivas-Lasarte, M.; Díaz-Rubio, E.; Zamora, E.; et al. Head-to-head comparison of contemporary heart failure risk scores. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 2035–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi, T.J.; Ahmed, A.; Greene, S.J.; Vaduganathan, M.; Fonarow, G.C.; Khan, S.S.; Butler, J.; Gheorghiade, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; McMurray, J.J.V.; et al. Performance of current risk stratification models for predicting mortality in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 2027–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.Y.; Cui, N.Q.; Jia, T.T.; Song, J.P.; Han, Y.L.; Liu, C.M.; Wang, X.F.; Chen, Z.Q.; Tang, Y.H.; Li, L. Prognostic models for patients suffering a heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction: A systematic review. ESC Heart Fail. 2024, 11, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, R.M.; Khan, S.S.; Shah, S.J.; Ahmad, F.S. Predicting high-risk patients and high-risk outcomes in heart failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 2020, 16, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golas, S.B.; Shibahara, T.; Agboola, S.; Otaki, H.; Sato, J.; Nakae, T.; Hisamitsu, T.; Kojima, G.; Zeidan, R.; Kvedar, J.C.; et al. A machine learning model to predict the risk of 30-day readmissions in patients with heart failure: A retrospective analysis of electronic medical records data. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.M.; Kim, K.H.; Jeon, K.H.; Lee, S.E.; Lee, H.Y.; Cho, H.J.; Choi, J.O.; Jeon, E.S.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, J.J.; et al. Artificial intelligence algorithm for predicting mortality of patients with acute heart failure. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.J.; Katz, D.H.; Selvaraj, S.; Burke, M.A.; Yancy, C.W.; Gheorghiade, M.; Bonow, R.O.; Huang, C.C.; Deo, R.C.; Agarwal, R.; et al. Phenomapping for novel classification of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 2015, 131, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, H.S.; Sheer, R.; Honarpour, N.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.L.; Lambert, C.T.; Desai, N.R.; Lokhnygina, Y.; Hernandez, A.F.; Fonarow, G.C. Real-world analysis of guideline-based therapy after hospitalization for heart failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartipy, U.; Dahlström, U.; Edner, M.; Lund, L.H. Predicting survival in heart failure: Validation of the MAGGIC heart failure risk score in 51,043 patients from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014, 16, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.C.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Vaduganathan, M.; Claggett, B.; Cunningham, J.W.; Zannad, F.; Packer, M.; Filippatos, G.; Butler, J.; Böhm, M.; et al. Finerenone in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrieri, G.; Limonta, R.; Ponti, E.; Ferrari, I.; Tarantini, L.; Musumeci, M.B.; Aspromonte, N.; Perrone Filardi, P.; Oliva, F.; Nodari, S.; et al. The therapy and management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: New insights on treatment. Card. Fail. Rev. 2024, 10, e05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Congestion Parameter | Target | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Parameters | ||

| Physical Examination |

| Salah et al. Heart 2014 [21] |

| NYHA Class |

| |

| Biomarkers | ||

| NT-proBNP |

| McQuade et al. 2017 [26] Salah et al. Heart 2014 [21] Kociol et al. Circ Heart Fail 2011 [23] |

| BNP |

| McQuade et al. 2017 [26] |

| Imaging | ||

| VExUS | VCI - maximum diameter < 2.1 cm - Collapsibility index > 50% Hepatic veins:

| Goonewardena et al. JACC Img 2008 [22] Stansen J, et al. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023 [16] |

| Lung Ultrasound |

| Platz et al. Eur J HF 2017 [15] |

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

|

| Lancellotti P et al. Eur HJ-CVI 2017 [24] Humbert et al. Eur Heart J 2022 [25] Guazzi et al. Am J Phisiol Heart Circ Phisiol 2017 [18] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rizzello, V.; Carigi, S.; De Maria, R.; Tinti, M.D.; Limonta, R.; Orso, F.; Bianco, M.; De Gennaro, L.; Matassini, M.V.; Manca, P.; et al. Risk Stratification Tools in Acute Heart Failure and Their Roles in Personalized Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8937. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248937

Rizzello V, Carigi S, De Maria R, Tinti MD, Limonta R, Orso F, Bianco M, De Gennaro L, Matassini MV, Manca P, et al. Risk Stratification Tools in Acute Heart Failure and Their Roles in Personalized Follow-Up. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8937. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248937

Chicago/Turabian StyleRizzello, Vittoria, Samuela Carigi, Renata De Maria, Maria Denitza Tinti, Raul Limonta, Francesco Orso, Matteo Bianco, Luisa De Gennaro, Maria Vittoria Matassini, Paolo Manca, and et al. 2025. "Risk Stratification Tools in Acute Heart Failure and Their Roles in Personalized Follow-Up" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8937. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248937

APA StyleRizzello, V., Carigi, S., De Maria, R., Tinti, M. D., Limonta, R., Orso, F., Bianco, M., De Gennaro, L., Matassini, M. V., Manca, P., Di Nora, C., Navazio, A., Geraci, G., Colivicchi, F., Bilato, C., Nardi, F., Grimaldi, M., & Oliva, F. (2025). Risk Stratification Tools in Acute Heart Failure and Their Roles in Personalized Follow-Up. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8937. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248937