Target-Controlled Infusion with PSI- and ANI-Guided Sufentanil Versus Remifentanil in Remimazolam-Based Total Intravenous Anesthesia for Postoperative Analgesia and Recovery After Laparoscopic Subtotal Gastrectomy: A Randomized Controlled Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

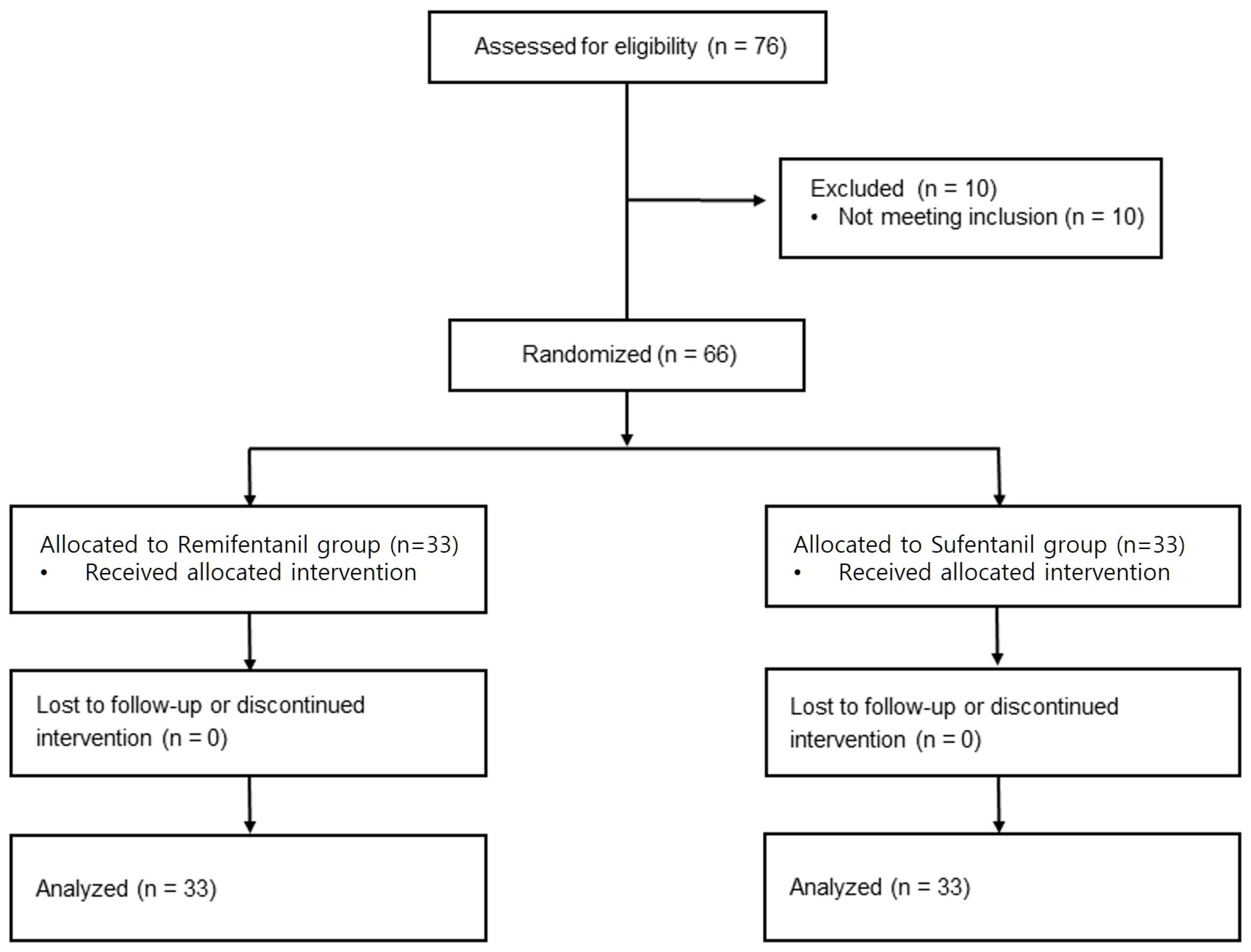

2.1. Study Populations

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Anesthetic Management

2.4. Postoperative Pain Management

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Statistical Analysis

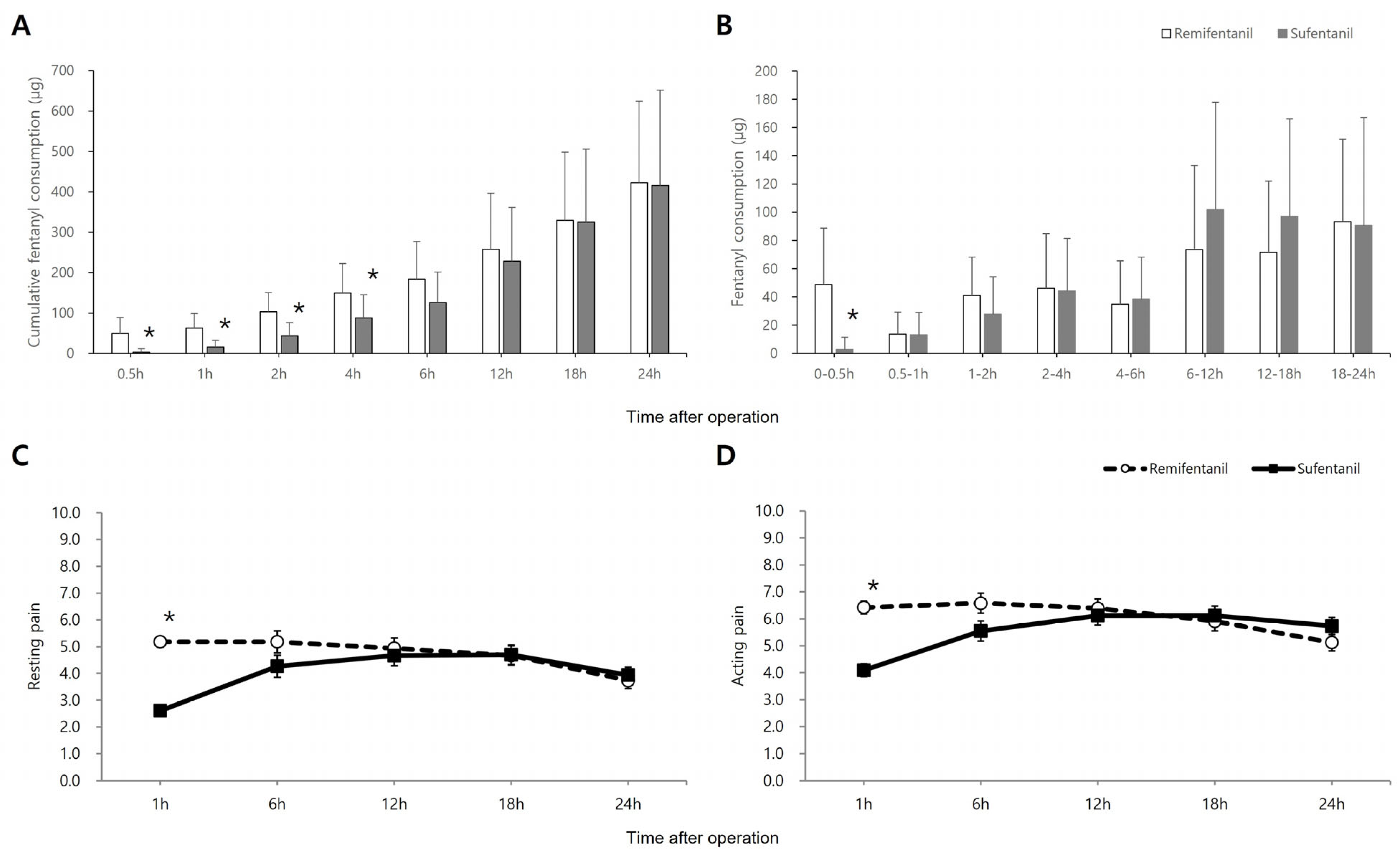

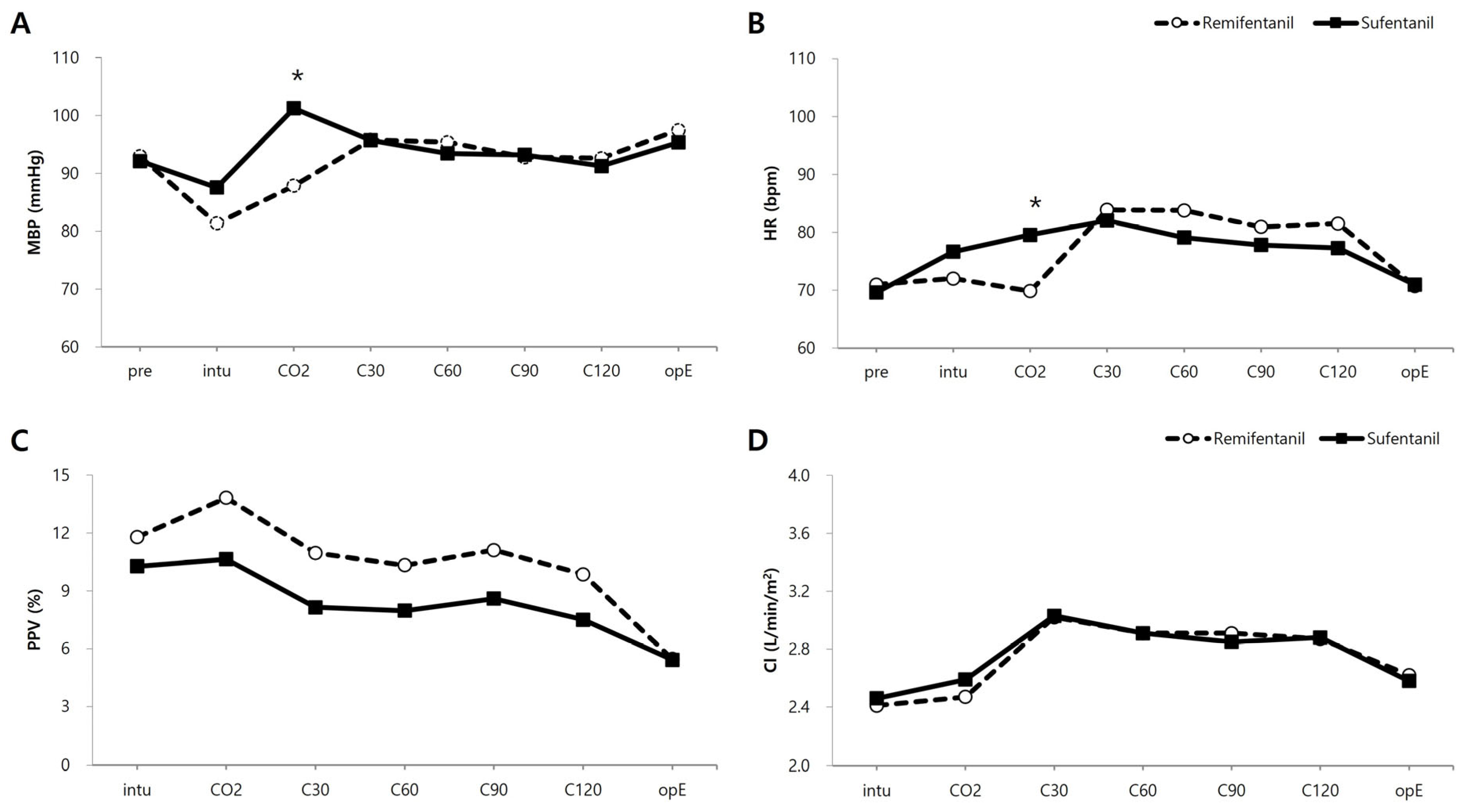

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TIVA | Total intravenous anesthesia |

| TCI | Target-controlled infusion |

| PCA | Patient-controlled analgesia |

| IRB | Institutional review boar |

| PSI | Patient State Index |

| ANI | Analgesia Nociception Index |

| MAP | Mean arterial pressure |

| HR | Heart rate |

| PACU | Post-anesthesia care unit |

| IV | Intravenously |

| NPRS | Numeric Pain Rating Scale |

| POD1 | Postoperative day 1 |

| QoR-40 | Quality of Recovery-40 |

| PPV | Pulse pressure variation |

| CI | Cardiac index |

References

- Minkowitz, H.S. Postoperative pain management in patients undergoing major surgery after remifentanil vs. Fentanyl anesthesia. Multicentre investigator group. Can. J. Anaesth. 2000, 47, 522–528. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.S.; Carpenter, R.L.; Mackey, D.C.; Thirlby, R.C.; Rupp, S.M.; Shine, T.S.; Feinglass, N.G.; Metzger, P.P.; Fulmer, J.T.; Smith, S.L. Effects of perioperative analgesic technique on rate of recovery after colon surgery. Anesthesiology 1995, 83, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guichard, L.; Hirve, A.; Demiri, M.; Martinez, V. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in patients with chronic pain: A systematic review of published cases. Clin. J. Pain 2021, 38, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absalom, A.R.; Glen, J.I.; Zwart, G.J.; Schnider, T.W.; Struys, M.M. Target-controlled infusion: A mature technology. Anesth. Analg. 2016, 122, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.P.; Rowbotham, D.J. Remifentanil—An opioid for the 21st century. Br. J. Anaesth. 1996, 76, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minto, C.F.; Schnider, T.W.; Shafer, S.L. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of remifentanil: II. Model application. Anesthesiology 1997, 86, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, M.A.; Glass, P.S.; Jacobs, J.R. Context-sensitive half-time in multicompartment pharmacokinetic models for intravenous anesthetic drugs. Anesthesiology 1992, 76, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gepts, E.; Shafer, S.L.; Camu, F.; Stanski, D.R.; Woestenborghs, R.; Van Peer, A.; Heykants, J.J. Linearity of pharmacokinetics and model estimation of sufentanil. Anesthesiology 1995, 83, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrode, N.; Lebrun, F.; Levron, J.C.; Chauvin, M.; Debaene, B. Influence of peroperative opioid on postoperative pain after major abdominal surgery: Sufentanil tci versus remifentanil tci. A randomized, controlled study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2003, 91, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorano, P.P.; Aloj, F.; Baietta, S.; Fiorelli, A.; Munari, M.; Paccagnella, F.; Rosa, G.; Scafuro, M.; Zei, E.; Falzetti, G.; et al. Sufentanil-propofol vs. remifentanil-propofol during total intravenous anesthesia for neurosurgery. A multicentre study. Minerva Anestesiol. 2008, 74, 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Colvin, L.A.; Bull, F.; Hales, T.G. Perioperative opioid analgesia-when is enough too much? A review of opioid-induced tolerance and hyperalgesia. Lancet 2019, 393, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M. Remimazolam: Pharmacological characteristics and clinical applications in anesthesiology. Anesth. Pain Med. 2022, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, C.H.; Lee, S.U.; Kim, H.G.; Lee, S.; Bae, Y.K.; Oh, A.Y.; Jeon, Y.T.; Ryu, J.H. Effect of remimazolam on intraoperative hemodynamic stability in patients undergoing cerebrovascular bypass surgery: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2025, 78, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Han, D.W.; Yang, J.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Song, Y. Comparison of remimazolam-based and propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia on postoperative quality of recovery: A randomized non-inferiority trial. J. Clin. Anesth. 2022, 82, 110955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liolios, A.; Guerit, J.M.; Scholtes, J.L.; Raftopoulos, C.; Hantson, P. Propofol infusion syndrome associated with short-term large-dose infusion during surgical anesthesia in an adult. Anesth. Analg. 2005, 100, 1804–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yi, J.M.; Joo, Y. The analgesia nociception index’s performance during remimazolam-based general anesthesia: A prospective observational study. Medicina 2025, 61, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, L.; Wu, X. Clinical value of total intravenous anesthesia with sufentanil and propofol in radical mastectomy. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 7294358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidgoli, J.; Delesalle, S.; De Hert, S.G.; Reiles, E.; Van der Linden, P.J. A randomised trial comparing sufentanil versus remifentanil for laparoscopic gastroplasty in the morbidly obese patient. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2011, 28, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.I.; Bae, J.; Song, Y.; Kim, M.; Han, D.W. Comparative analysis of the performance of electroencephalogram parameters for monitoring the depth of sedation during remimazolam target-controlled infusion. Anesth. Analg. 2024, 138, 1295–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.K.; Lee, I.O.; Lim, B.G.; Jeong, H.; Kim, Y.S.; Ji, S.G.; Park, J.S. Comparison of the analgesic effect of sufentanil versus fentanyl in intravenous patient-controlled analgesia after total laparoscopic hysterectomy: A randomized, double-blind, prospective study. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 16, 1439–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, T.D. Remifentanil pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. A preliminary appraisal. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1995, 29, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djian, M.C.; Blanchet, B.; Pesce, F.; Sermet, A.; Disdet, M.; Vazquez, V.; Gury, C.; Roux, F.X.; Raggueneau, J.L.; Coste, J.; et al. Comparison of the time to extubation after use of remifentanil or sufentanil in combination with propofol as anesthesia in adults undergoing nonemergency intracranial surgery: A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Clin. Ther. 2006, 28, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, J. Sufentanil target controlled infusion (tci) versus remifentanil tci for monitored anaesthesia care for patients with severe tracheal stenosis undergoing fiberoptic bronchoscopy: Protocol for a prospective, randomised, controlled study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Wen, X.; Mei, X.; Fang, F.; Zhang, T. Mechanisms of remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia: A comprehensive review. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2025, 19, 7445–7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, T.M.; Giraud, G.D.; Togioka, B.M.; Jones, D.B.; Cigarroa, J.E. Cardiovascular and ventilatory consequences of laparoscopic surgery. Circulation 2017, 135, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, I.K.; Kim, J.S.; Hur, H.; Han, D.G.; Kim, J.E. Effects of deep neuromuscular block on surgical pleth index-guided remifentanil administration in laparoscopic herniorrhaphy: A prospective randomized trial. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasian, H.N.; Margarit, S.; Ionescu, D.; Keresztes, A.; Arpasteuan, B.; Condruz, N.; Coada, C.; Acalovschi, I. Total intravenous anesthesia-target controlled infusion for colorectal surgery. Remifentanil tci vs. sufentanil tci. Rom. J. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2014, 21, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Kim, M.H.; Kong, H.J.; Shin, H.J.; Yang, S.; Kim, N.Y.; Chae, D. Effects of remimazolam vs. Sevoflurane anesthesia on intraoperative hemodynamics in patients with gastric cancer undergoing robotic gastrectomy: A propensity score-matched analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, P.S.; Weitkamp, B.; Jones, K.; Melick, J.; Hensen, S. Validity and reliability of a postoperative quality of recovery score: The qor-40. Br. J. Anaesth. 2000, 84, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Baerdemaeker, L.E.; Jacobs, S.; Pattyn, P.; Mortier, E.P.; Struys, M.M. Influence of intraoperative opioid on postoperative pain and pulmonary function after laparoscopic gastric banding: Remifentanil tci vs. sufentanil tci in morbid obesity. Br. J. Anaesth. 2007, 99, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Liu, J. Remimazolam-remifentanil causes less postoperative nausea and vomiting than remimazolam-alfentanil during hysteroscopy: A single-centre randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023, 23, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hari, Y.; Satomi, S.; Murakami, C.; Narasaki, S.; Morio, A.; Kato, T.; Tsutsumi, Y.M.; Kakuta, N.; Tanaka, K. Remimazolam decreased the incidence of early postoperative nausea and vomiting compared to desflurane after laparoscopic gynecological surgery. J. Anesth. 2022, 36, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Hong, M.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, H.S.; Kwon, Y.S.; Lee, J.J. Effect of body mass index on postoperative nausea and vomiting: Propensity analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranke, P.; Apfel, C.C.; Papenfuss, T.; Rauch, S.; Löbmann, U.; Rübsam, B.; Greim, C.A.; Roewer, N. An increased body mass index is no risk factor for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2001, 45, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Remifentanil Group (n = 33) | Sufentanil Group (n = 33) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.85 | ± | 9.42 | 58.36 | ± | 10.24 | 0.155 |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 17 (51.5) | / | 16 (48.5) | 20 (60.6) | / | 13 (39.4) | 0.457 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.56 | ± | 3.17 | 22.64 | ± | 3.11 | 0.915 |

| ASA physical status | 0.091 | ||||||

| 1 | 6 | [18.18] | 9 | [27.27] | |||

| 2 | 17 | [51.52] | 21 | [63.64] | |||

| 3 | 10 | [30.30] | 3 | [9.09] | |||

| History of PONV and/or motion sickness | 10 | [30.30] | 8 | [24.24] | 0.580 | ||

| Smoking history | 0.217 | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | 23 | [69.70] | 19 | [57.58] | |||

| Ex-smoker | 6 | [18.18] | 12 | [36.36] | |||

| Current smoker | 4 | [12.12] | 2 | [6.06] | |||

| Apfel score | 2.62 | ± | 1.02 | 2.58 | ± | 0.87 | 0.698 |

| Variables | Remifentanil Group (n = 33) | Sufentanil Group (n = 33) | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to loss of consciousness, sec | 140.39 | ± | 32.59 | 153.03 | ± | 38.21 | 0.153 | |

| Anesthesia time, min | 221.42 | ± | 57.15 | 207.06 | ± | 39.78 | 0.241 | |

| Operation time, min | 184.18 | ± | 57.65 | 170.12 | ± | 40.97 | 0.258 | |

| Total fluid intake, mL | 1677.27 | ± | 395.70 | 1554.55 | ± | 403.18 | 0.217 | |

| Blood loss, mL | 75.82 | ± | 68.86 | 51.18 | ± | 53.16 | 0.109 | |

| Urine output, mL | 287.36 | ± | 167.18 | 291.97 | ± | 307.91 | 0.940 | |

| Intraoperative administered anesthetics | ||||||||

| Remifentanil, µg | 1375.36 | ± | 524.20 | - | ||||

| Sufentanil, µg | 59.86 | ± | 22.08 | - | ||||

| Remimazolam, µg | 286.41 | ± | 97.59 | 271.39 | ± | 87.11 | 0.512 | |

| Intraoperative vasoactive drugs | ||||||||

| Nicardipine, n | 1 | [3.03] | 2 | [6.06] | >0.999 | |||

| Nicardipine, µg | 45.45 | ± | 261.12 | 36.36 | ± | 163.59 | 0.866 | |

| Phenylephrine, n | 7 | [21.21] | 3 | [9.09] | 0.170 | |||

| Phenylephrine, µg | 209.03 | ± | 916.36 | 186.67 | ± | 706.48 | 0.912 | |

| Ephedrine, n | 7 | [21.21] | 5 | [15.15] | 0.523 | |||

| Ephedrine, mg | 1.58 | ± | 3.73 | 0.97 | ± | 2.60 | 0.448 | |

| Operative findings | ||||||||

| Intraoperative adhesion | ||||||||

| (none/mild/moderate/severe) | 0.708 | |||||||

| None | 5 | [15.15] | 7 | [21.21] | ||||

| Mild | 23 | [69.70] | 24 | [72.73] | ||||

| Moderate | 3 | [9.09] | 1 | [3.03] | ||||

| Severe | 2 | [6.06] | 1 | [3.03] | ||||

| Omentectomy | 0.492 | |||||||

| (not done/partial/complete) | ||||||||

| not done | 0 | [0] | 1 | [3.03] | ||||

| Partial | 33 | [100] | 31 | [93.94] | ||||

| Complete | 0 | [0] | 1 | [3.03] | ||||

| Variables | Remifentanil Group (n = 33) | Sufentanil Group (n = 33) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Fentanyl Consumption (24 h), µg | 422.39 | ± | 201.61 | 415.55 | ± | 236.64 | 0.900 |

| Maximal NPRS score (0–10) | 5.24 | ± | 1.03 | 2.61 | ± | 1.17 | <0.001 |

| Rescue analgesics, n | 26 | [78.79] | 2 | [6.06] | <0.001 | ||

| Rescue analgesics, µg | 40 | [25–50] | 0 | [0–0] | <0.001 | ||

| Variables | Remifentanil Group (n = 33) | Sufentanil Group (n = 33) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to extubation, sec | 291 | ± | 119 | 319 | ± | 105 | 0.318 |

| SAS at emergence (1–7) | 3.94 | ± | 0.24 | 3.85 | ± | 0.36 | 0.238 |

| Recovery room data | |||||||

| SAS at PACU admission (1–7) | 3.91 | ± | 0.29 | 3.52 | ± | 0.51 | <0.001 |

| Nausea, n | 2 | [6.06] | 1 | [3.03] | >0.999 | ||

| Vomiting, n | 0 | [0.00] | 0 | [0.00] | - | ||

| PACU stay, min | 61.48 | ± | 25.71 | 51.73 | ± | 30.96 | 0.169 |

| QoR-40 on POD1 | |||||||

| Physical comfort | 47.12 | ± | 5.78 | 44.33 | ± | 6.85 | 0.079 |

| Physical independence | 14.82 | ± | 4.86 | 13.97 | ± | 4.56 | 0.468 |

| Emotional status | 34.79 | ± | 5.77 | 34.00 | ± | 6.09 | 0.591 |

| Psychological support | 29.30 | ± | 5.76 | 29.61 | ± | 4.29 | 0.809 |

| Pain | 28.70 | ± | 4.07 | 27.73 | ± | 4.72 | 0.375 |

| Global QoR-40 score | 154.73 | ± | 18.41 | 149.64 | ± | 21.04 | 0.299 |

| PONV on POD1 | |||||||

| Nausea, n | 9 | [27] | 17 | [52] | 0.085 | ||

| Vomiting, n | 3 | [9] | 4 | [12] | >0.999 | ||

| Patient satisfaction score (1–4) | 2.85 | ± | 0.71 | 2.70 | ± | 0.73 | 0.396 |

| Postoperative hospital stays, days | 5.15 | ± | 1.28 | 5.12 | ± | 0.86 | 0.910 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jun, B.; Yoo, Y.C.; Bai, S.J.; Shin, H.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, N.Y.; Moon, J. Target-Controlled Infusion with PSI- and ANI-Guided Sufentanil Versus Remifentanil in Remimazolam-Based Total Intravenous Anesthesia for Postoperative Analgesia and Recovery After Laparoscopic Subtotal Gastrectomy: A Randomized Controlled Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8921. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248921

Jun B, Yoo YC, Bai SJ, Shin HJ, Kim J, Kim NY, Moon J. Target-Controlled Infusion with PSI- and ANI-Guided Sufentanil Versus Remifentanil in Remimazolam-Based Total Intravenous Anesthesia for Postoperative Analgesia and Recovery After Laparoscopic Subtotal Gastrectomy: A Randomized Controlled Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8921. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248921

Chicago/Turabian StyleJun, Byongnam, Young Chul Yoo, Sun Joon Bai, Hye Jung Shin, Jinmok Kim, Na Young Kim, and Jiae Moon. 2025. "Target-Controlled Infusion with PSI- and ANI-Guided Sufentanil Versus Remifentanil in Remimazolam-Based Total Intravenous Anesthesia for Postoperative Analgesia and Recovery After Laparoscopic Subtotal Gastrectomy: A Randomized Controlled Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8921. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248921

APA StyleJun, B., Yoo, Y. C., Bai, S. J., Shin, H. J., Kim, J., Kim, N. Y., & Moon, J. (2025). Target-Controlled Infusion with PSI- and ANI-Guided Sufentanil Versus Remifentanil in Remimazolam-Based Total Intravenous Anesthesia for Postoperative Analgesia and Recovery After Laparoscopic Subtotal Gastrectomy: A Randomized Controlled Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8921. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248921