Prostate Artery Embolization vs. Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate: A Matched Pair Analysis of Functional Outcomes and Complications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Rationale for Matching and Study Design

2.3. General Assessment

2.4. Interventional Procedure

2.5. Surgical Procedure

2.6. Endpoints

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Baseline Characteristics

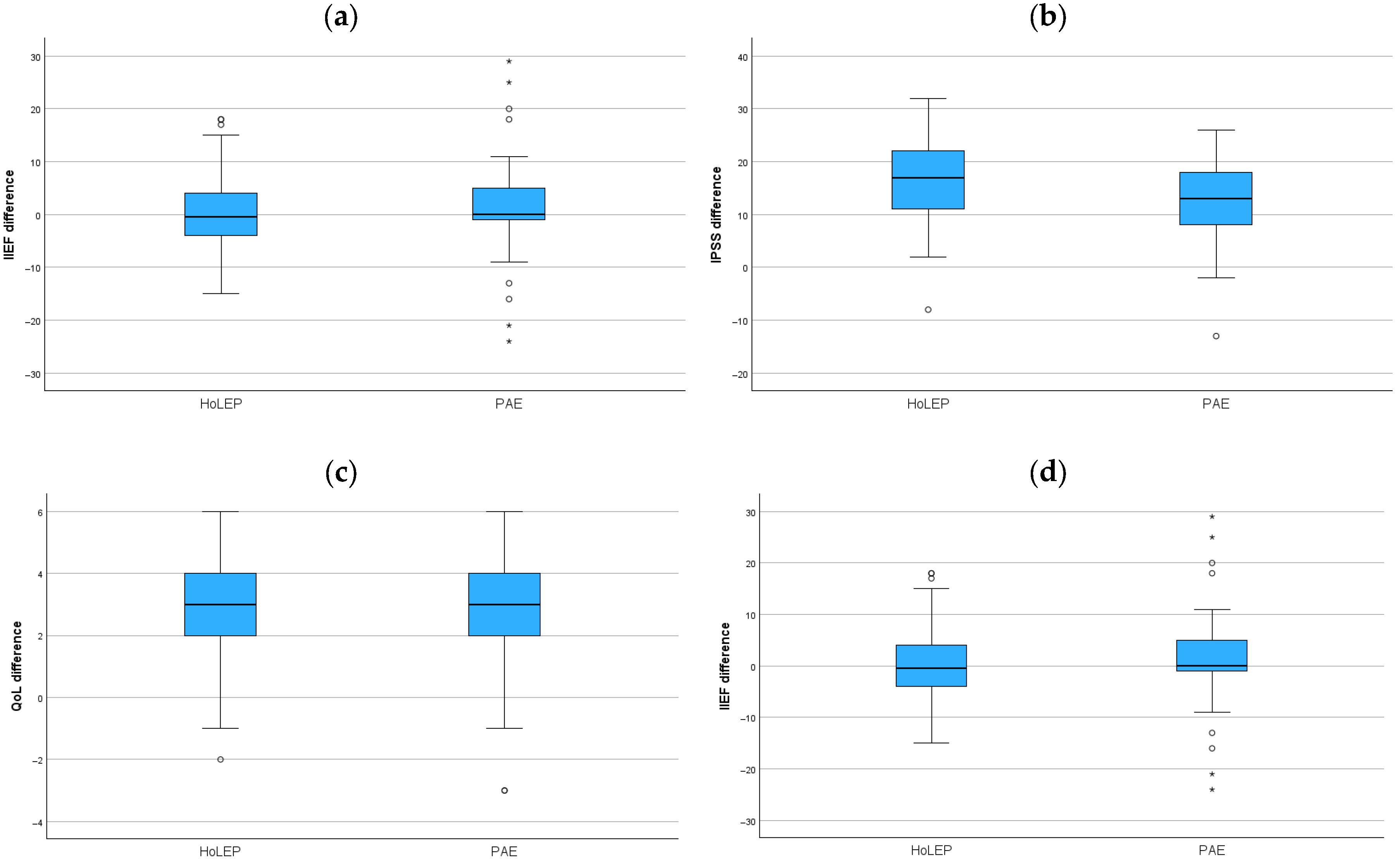

3. Functional Results

Complications

4. Discussion

- The limited cohort size inherently constrained the matching process and the statistical power of the study. Because only a fixed number of suitable matches were available, the inclusion of additional baseline variables in the propensity score model was not feasible without losing a substantial proportion of cases. Although PSA and IIEF differed between groups at baseline, these variables were therefore not included in the matching algorithm. PSA was omitted because it is not directly associated with LUTS severity or functional outcome parameters (IPSS, Qmax, QoL, IIEF) and was unlikely to confound the primary analyses. IIEF, despite its clinical relevance, could not be incorporated because no matching configuration produced adequate balance while preserving a sufficient sample size. Consequently, the baseline imbalance in IIEF must be acknowledged as a major limitation. Postoperative changes in IIEF were small in both groups, reducing the risk of significant bias in the comparison of erectile-function outcomes. Furthermore, no formal power calculation was performed. A meaningful a priori power analysis would have required predefined effect sizes and the ability to increase the sample accordingly; however, this was not possible in a retrospective matched-pair design with a fixed number of eligible controls. Thus, the study is not powered to detect minimal clinically important differences between groups.

- The follow-up schedules for HoLEP patients in our study were not standardized, unlike the uniform 6-month follow-up implemented for the PAE cohort. This heterogeneity introduces a risk of temporal bias and could not be rectified through statistical tests, indicating a significant limitation in the study. Given the unequal follow-up durations, results were interpreted as cross-sectional comparisons rather than time-matched longitudinal outcomes. However, long-term studies indicate that key outcomes such as IPSS, Qmax, QoL, and erectile function stabilize after the first year post-HoLEP and remain durable up to 10 years in about 75% of cases [24].Likewise, PAE has demonstrated sustained symptom relief and low complication rates over 5–6 years [25]. These findings support our assumption that temporal variations in follow-up may have limited impact on the observed outcomes. Also, recent long-term studies have demonstrated that the outcomes of PAE remain stable over time, indicating that meaningful comparisons can still be made despite differences in follow-up intervals [15]. However, as the HoLEP cohort had substantially longer follow-up, whereas PAE outcomes were assessed at six months, the full therapeutic effect of PAE may not yet have been captured, potentially leading to a slight overestimation of the relative HoLEP benefit. Still, future studies should employ harmonized follow-up intervals to eliminate potential bias.

- There is a variability in surgical experience. Since PAE is a relatively new procedure, the learning curve is a major factor in determining success rates and complications. Variations in operator expertise can critically influence the results of both interventions. In our PAE group, some procedures occurred during the early phase of the interventional radiologists’ learning curve, which could have affected technical success and complication rates. A study of 296 consecutive PAE procedures by radiologists without prior experience demonstrated that technical efficiency improved markedly after approximately 73–78 cases, confirming that early-stage operator inexperience diminishes with experience [26]. For HoLEP, outcomes have been shown to become consistent after approximately 40 procedures, depending on surgeon experience and institutional case volume. In the present study, the individual experience of the HoLEP surgeons was not documented in detail and therefore could not be directly compared with that of the interventional radiologists. However, as PAE was still a relatively new technique at the time of data acquisition, it is likely that the interventional radiologists were at an earlier stage of their learning curve. Conversely, the HoLEP surgeons may have had greater prior experience, although this assumption cannot be confirmed based on the available data.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPH | Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia |

| BOO | Bladder Outlet Obstruction |

| DRE | Digital Rectal Examination |

| HoLEP | Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate |

| IIEF | International Index of Erectile Function |

| IPSS | International Prostate Symptom Score |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| LUTS | Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms |

| PAE | Prostate Artery Embolization |

| PES | Postembolization Syndrome |

| PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| Qmax | Maximum Urinary Flow Rate |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TURP | Transurethral Resection of the Prostate |

References

- Verhamme, K.M.; Dieleman, J.P.; Bleumink, G.S.; van der Lei, J.; Sturkenboom, M.C.; Artibani, W.; Panel, T.P.E.E. Incidence and prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care—The Triumph project. Eur. Urol. 2002, 42, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, O.; Gratzke, C.; Stief, C.G. Techniques and long-term results of surgical procedures for BPH. Eur. Urol. 2006, 49, 970–978; discussion 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, E. Minimally invasive surgical treatments for male lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic enlargement: A review on sexual function outcomes. Bladder 2025, 12, e21200051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalak, J.; Tzou, D.; Funk, J. HoLEP: The gold standard for the surgical management of BPH in the 21(st) Century. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 2015, 3, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Elzayat, E.A.; Habib, E.I.; Elhilali, M.M. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate: A size-independent new “gold standard”. Urology 2005, 66, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baboudjian, M.; Hashim, H.; Bhatt, N.; Creta, M.; De Nunzio, C.; Gacci, M.; Herrmann, T.; Karavitakis, M.; Malde, S.; Moris, L.; et al. Summary Paper on Underactive Bladder from the European Association of Urology Guidelines on Non-neurogenic Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichgräber, U.; Aschenbach, R.; Diamantis, I.; von Rundstedt, F.C.; Grimm, M.O.; Franiel, T. Prostate Artery Embolization: Indication, Technique and Clinical Results. Rofo 2018, 190, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, F.C.; Antunes, A.A.; da Motta Leal Filho, J.M.; de Oliveira Cerri, L.M.; Baroni, R.H.; Marcelino, A.S.; Freire, G.C.; Moreira, A.M.; Srougi, M.; Cerri, G.G. Prostatic artery embolization as a primary treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia: Preliminary results in two patients. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2010, 33, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abt, D.; Hechelhammer, L.; Müllhaupt, G.; Markart, S.; Güsewell, S.; Kessler, T.M.; Schmid, H.-P.; Engeler, D.S.; Mordasini, L. Comparison of prostatic artery embolisation (PAE) versus transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for benign prostatic hyperplasia: Randomised, open label, non-inferiority trial. BMJ 2018, 361, k2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glybochko, P.V.; Rapoport, L.M.; Enikeev, M.E.; Enikeev, D.V. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) for small, large and giant prostatic hyperplasia: Tips and tricks. Urol. J. 2017, 84, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderlein, G.F.; Lehmann, T.; von Rundstedt, F.C.; Aschenbach, R.; Grimm, M.O.; Teichgräber, U.; Franiel, T. Prostatic Artery Embolization-Anatomic Predictors of Technical Outcomes. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 31, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gild, P.; Lenke, L.; Pompe, R.S.; Vetterlein, M.W.; Ludwig, T.A.; Soave, A.; Chun, F.K.-H.; Ahyai, S.; Dahlem, R.; Fisch, M.; et al. Assessing the Outcome of Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate by Age, Prostate Volume, and a History of Blood Thinning Agents: Report from a Single-Center Series of >1800 Consecutive Cases. J. Endourol. 2021, 35, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, H.N.; Mahajan, A.P.; Hegde, S.S.; Bansal, M.B. Peri-operative complications of holmium laser enucleation of the prostate: Experience in the first 280 patients, and a review of literature. BJU Int. 2007, 100, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müllhaupt, G.; Hechelhammer, L.; Graf, N.; Mordasini, L.; Schmid, H.P.; Engeler, D.S.; Abt, D. Prostatic Artery Embolisation Versus Transurethral Resection of the Prostate for Benign Prostatic Obstruction: 5-year Outcomes of a Randomised, Open-label, Noninferiority Trial. Eur. Urol. Focus 2024, 10, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapoval, M.R.; Bhatia, S.; Déan, C.; Rampoldi, A.; Carnevale, F.C.; Bent, C.; Tapping, C.R.; Bongiovanni, S.; Taylor, J.; Brower, J.S.; et al. Two-Year Outcomes of Prostatic Artery Embolization for Symptomatic Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: An International, Multicenter, Prospective Study. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2024, 47, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Guo, L.; Duan, F.; Yuan, K.; Zhang, G.; Li, K.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y.; Kang, H. Prostatic arterial embolization for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia: A comparative study of medium- and large-volume prostates. BJU Int. 2016, 117, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uflacker, A.; Haskal, Z.J.; Bilhim, T.; Patrie, J.; Huber, T.; Pisco, J.M. Meta-Analysis of Prostatic Artery Embolization for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2016, 27, 1686–1697.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malling, B.; Røder, M.A.; Brasso, K.; Forman, J.; Taudorf, M.; Lönn, L. Prostate artery embolisation for benign prostatic hyperplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ini, C.; Vasile, T.; Foti, P.V.; Timpanaro, C.; Castiglione, D.G.; Libra, F.; Falsaperla, D.; Tiralongo, F.; Giurazza, F.; Mosconi, C.; et al. Prostate Artery Embolization as Minimally Invasive Treatment for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: An Updated Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svarc, P.; Taudorf, M.; Nielsen, M.B.; Stroomberg, H.V.; Røder, M.A.; Lönn, L. Postembolization Syndrome after Prostatic Artery Embolization: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Liu, H.; Xu, D.; Xu, L.; Huang, F.; He, W.; Qi, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, D. Functional outcomes and complications following B-TURP versus HoLEP for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: A review of the literature and Meta-analysis. Aging Male 2017, 20, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotsenko, P.; Wetterauer, C.; Grimsehl, P.; Möltgen, T.; Meierhans, S.; Manka, L.; Seifert, H.; Wyler, S.; Kwiatkowski, M. Efficacy, safety, and perioperative outcomes of holmium laser enucleation of the prostate-a comparison of patients with lower urinary tract symptoms and urinary retention. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallara, G.; Capogrosso, P.; Schifano, N.; Costa, A.; Candela, L.; Cazzaniga, W.; Boeri, L.; Belladelli, F.; Scattoni, V.; Salonia, A.; et al. Ten-year Follow-up Results After Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate. Eur. Urol. Focus 2021, 7, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisco, J.M.; Bilhim, T.; Pinheiro, L.C.; Fernandes, L.; Pereira, J.; Costa, N.V.; Duarte, M.; Oliveira, A.G. Medium- and Long-Term Outcome of Prostate Artery Embolization for Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Results in 630 Patients. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2016, 27, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, T.; Rahman, S.; Staib, L.; Bhatia, S.; Ayyagari, R. Operator Learning Curve for Prostatic Artery Embolization and Its Impact on Outcomes in 296 Patients. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 46, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshal, A.M.; Nabeeh, H.; Eldemerdash, Y.; Mekkawy, R.; Laymon, M.; El-Assmy, A.; El-Nahas, A.R. Prospective Assessment of Learning Curve of Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate for Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Using a Multidimensional Approach. J. Urol. 2017, 197, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | HoLEP | PAE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. pts (n) | 69 | 69 | |

| Age (y) | 66 (62–71) | 67 (58–72) | 0.8 |

| Prostate Volume (mL) | 75 (55–100) | 61.8 (44.7–97.9) | 0.050 |

| PSA (ng/mL) | 4.9 (2.4–9) | 2.4 (1.5–5.4) | 0.001 |

| IIEF | 18.5 (6.0–21) | 23 (9.5–26) | 0.002 |

| IPSS | 23 (16.5–27) | 23 (17.5–26) | 0.7 |

| QoL | 4 (4–5) | 5 (4–5) | 0.2 |

| Qmax (mL/s) | 10.6 (6.5–13.9) | 10.0 (6–13) | 0.4 |

| Parameter | Preop | Postop | Difference | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HoLEP pts (n) | 69 | 69 | ||

| IIEF | 18.5 (6.0–21) | 15 (8–23) | −0.5 (−4–4) | 0.9 |

| IPSS | 23 (16.5–27) | 4 (1–8.5) | 17 (10.5–22) * | <0.001 |

| QoL | 4 (4–5) | 1 (0–2) | 3 (2–4) * | <0.001 |

| Qmax (mL/s) | 10.6 (6.5–13.9) | 25 (16.8–33.2) | 14.9 (10.2–25.9) | <0.001 |

| PAE pts (n) | 69 | 69 | ||

| IIEF | 23 (9.5–26) | 24 (10–29.5) | 0 (−1–5) | 0.2 |

| IPSS | 23 (17.5–26) | 8 (5–13) | 13 (8–18.5) * | <0.001 |

| QoL | 5 (4–5) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) * | <0.001 |

| Qmax (mL/s) | 10 (6–13) | 15.9 (7.7–19.7) | 5.8 (2.2–9.2) | <0.001 |

| Grade/Complication | HoLEP | PAE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 69) | (n = 69) | ||

| Grade I (all) | 9 (13.0%) | 8 (11.6%) | 1.0 |

| -Grade I complications other than postop pain | 3 (4.3%) | 8 (11.6%) | 0.21 |

| Grade II (all) | 5 (7.2%) | 3 (4.3%) | 0.7 |

| Grade IIIa (all) | 2 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.5 |

| Grade IV, V (all) | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leschik, S.H.F.; Große Siemer, R.; von Rundstedt, F.-C.; Gild, P.; Meyer, C.P.; Abrams-Pompe, R.S.; Teichgraeber, U.; Lehmann, T.; Foller, S.; Grimm, M.-O.; et al. Prostate Artery Embolization vs. Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate: A Matched Pair Analysis of Functional Outcomes and Complications. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8906. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248906

Leschik SHF, Große Siemer R, von Rundstedt F-C, Gild P, Meyer CP, Abrams-Pompe RS, Teichgraeber U, Lehmann T, Foller S, Grimm M-O, et al. Prostate Artery Embolization vs. Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate: A Matched Pair Analysis of Functional Outcomes and Complications. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8906. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248906

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeschik, Simon Hannes Friedrich, Robert Große Siemer, Friedrich-Carl von Rundstedt, Philipp Gild, Christian P. Meyer, Raisa S. Abrams-Pompe, Ulf Teichgraeber, Thomas Lehmann, Susan Foller, Marc-Oliver Grimm, and et al. 2025. "Prostate Artery Embolization vs. Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate: A Matched Pair Analysis of Functional Outcomes and Complications" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8906. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248906

APA StyleLeschik, S. H. F., Große Siemer, R., von Rundstedt, F.-C., Gild, P., Meyer, C. P., Abrams-Pompe, R. S., Teichgraeber, U., Lehmann, T., Foller, S., Grimm, M.-O., & Franiel, T. (2025). Prostate Artery Embolization vs. Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate: A Matched Pair Analysis of Functional Outcomes and Complications. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8906. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248906