Effect of Previous Cesarean Section on Labor Progression: Comparison Between First VBAC and Primiparous Vaginal Deliveries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Study design:

- 2.

- Setting:

- 3.

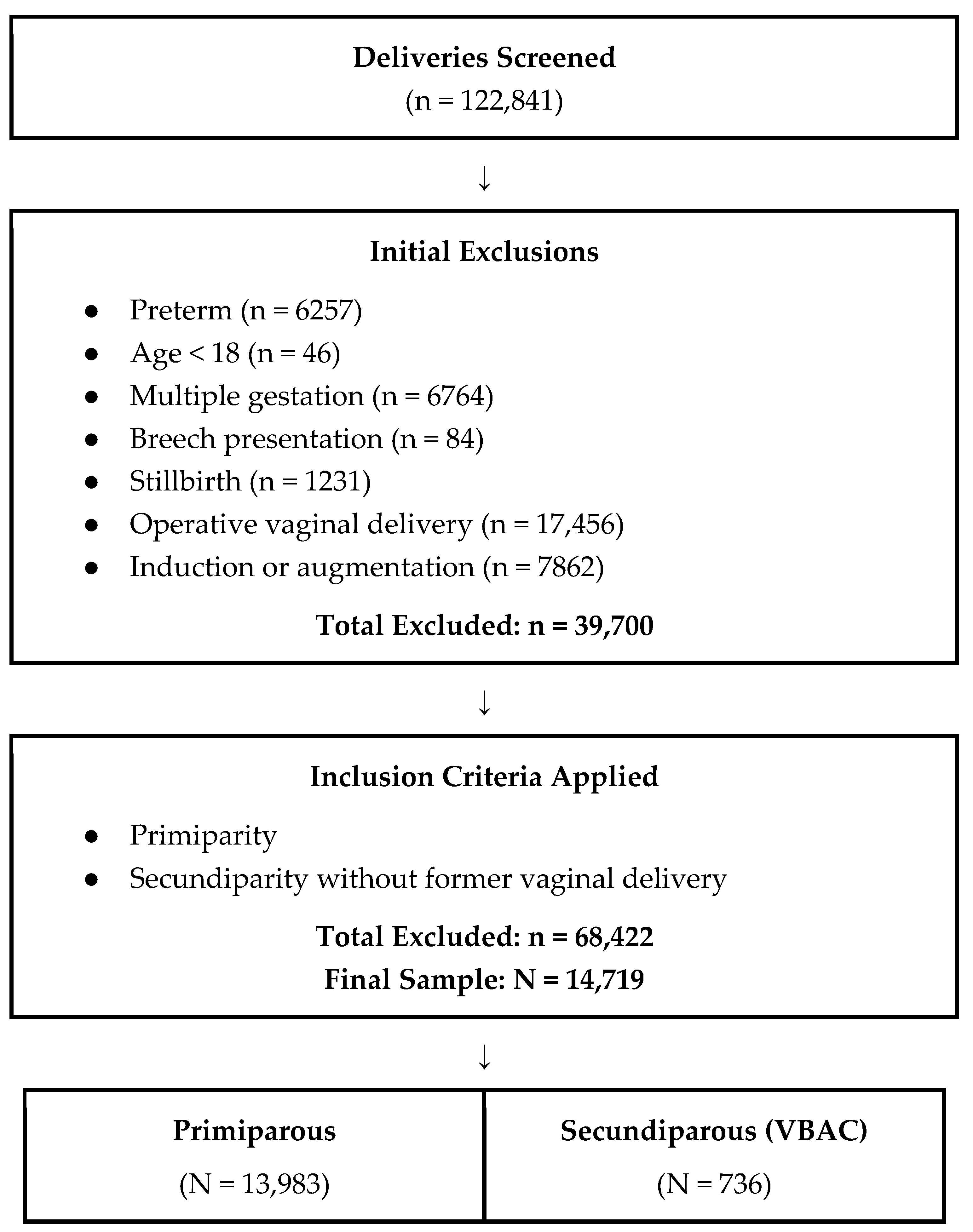

- Participants:

- 4.

- Data collection:

- 5.

- Data source:

- 6.

- Missing Data:

- 7.

- Bias:

- 8.

- Statistical Analysis:

- 9.

- Ethical approval:

3. Results

4. Discussion

- 10.

- Limitations and Strengths:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VBAC | Vaginal Birth After Cesarean |

| TOLAC | Trial of Labor After Cesarean |

| PSS | Prolonged Second Stage |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

References

- Betrán, A.P.; Ye, J.; Moller, A.B.; Zhang, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Torloni, M.R. The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990–2014. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Troendle, J.; Reddy, U.M.; Laughon, S.K.; Branch, D.W.; Burkman, R.; Landy, H.J.; Hibbard, J.U.; Haberman, S.; Ramirez, M.M.; et al. Contemporary cesarean delivery practice in the United States. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, 326.e1–326.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentilhes, L.; Vayssière, C.; Beucher, G.; Deneux-Tharaux, C.; Deruelle, P.; Diemunsch, P.; Gallot, D.; Haumonté, J.-B.; Heimann, S.; Kayem, G.; et al. Delivery for women with a previous cesarean: Guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 170, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betrán, A.P.; Temmerman, M.; Kingdon, C.; Mohiddin, A.; Opiyo, N.; Torloni, M.R.; Zhang, J.; Musana, O.; Wanyonyi, S.Z.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; et al. Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. Lancet 2018, 392, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Panel. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development conference statement: Vaginal birth after cesarean: New insights March 8–10, 2010. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 115, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ayres-de-Campos, D.; Simon, A.; Modi, N.; Tudose, M.; Saliba, E.; Wielgos, M.; Reyns, M.; Athanasiadis, A.; Stenback, P.; Verlohren, S.; et al. European Association of Perinatal Medicine (Eapm) European Midwives Association (EMA). Joint position statement: Caesarean delivery rates at a country level should be in the 15–20% range. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 294, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice bulletin no. 205: Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, e110–e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimovsky, A.C. Evidence-based labor management: Second stage of labor (part 4). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 4, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, E.R.; Ramasauskaite, D.; Ubom, A.E.; Di Simone, N.; Mueller, M.; Borovac-Pinheiro, A.; Guarano, A.; Benedetto, C.; Beyeza-Kashesya, J.; Nunes, I.; et al. FIGO good practice recommendations for vaginal birth after cesarean section. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2025, 171, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houri, O.; Bercovich, O.; Berezovsky, A.; Gruber, S.D.; Pardo, A.; Werthimer, A.; Walfisch, A.; Hadar, E. Success Rate and Obstetric Outcomes of Trial of Labor After Cesarean Delivery-Decision-Tree Analysis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2025, 171, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalev-Ram, H.; Miller, N.; David, L.; Issakov, G.; Weinberger, H.; Biron-Shental, T. Spontaneous labor patterns among women attempting vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 9325–9330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graseck, A.S.; Odibo, A.O.; Tuuli, M.; Roehl, K.A.; Macones, G.A.; Cahill, A.G. Normal first stage of labor in women undergoing trial of labor after cesarean delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 119, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazotte, C.; Madden, R.; Cohen, W.R. Labor patterns in women with previous cesareans. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 75, 350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Karampas, G.; Witkowski, M.; Metallinou, D.; Steinwall, M.; Matsas, A.; Panoskaltsis, T.; Christopoulos, P. Delivery Progress, Labor Interventions and Perinatal Outcome in Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery of Singleton Pregnancies between Nulliparous and Primiparous Women with One Previous Elective Cesarean Section: A Retrospective Comparative Study. Life 2023, 13, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantz, K.L.; Gonzalez-Quintero, V.; Troendle, J.; Reddy, U.M.; Hinkle, S.N.; Kominiarek, M.A.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, J. patterns in women attempting vaginal birth after cesarean with normal neonatal outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 226.e1–226.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Pan, S.; Chen, B.; Peng, L.; Chen, R.; Hua, Y.; Ma, Y. Labor characteristics and intrapartum interventions in women with vaginal birth after cesarean section. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yang, L.; Peng, J.; Cheng, W.; Ma, H.; Wu, S.; Wen, J.; Zhao, Y. Duration time of labor progression for pregnant women of vaginal birth after cesarean in Hubei, China. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 193, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughon, S.K.; Branch, D.W.; Beaver, J.; Zhang, J. Changes in labor patterns over 50 years. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 206, 419.e1–419.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.W.; Shaffer, B.L.; Nicholson, J.M.; Caughey, A.B. Second stage of labor and epidural use: A larger effect than previously suggested. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 123, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion number 269 February 2002. Analgesia and cesarean delivery rates. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 99, 369–370. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, N.; Pellegg, M.; Hag-Yahia, N.; Daykan, Y.; Pasternak, Y.; Biron-Shental, T. Labor progression of women attempting vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery with or without epidural analgesia. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 299, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Landy, H.J.; Branch, D.W.; Burkman, R.; Haberman, S.; Gregory, K.D.; Hatjis, C.G.; Ramirez, M.M.; Bailit, J.L.; Gonzalez-Quintero, V.H.; et al. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 116, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arulkumaran, S.; Gibb, D.M.F.; Lun, K.C.; Heng, S.H.; Ratnam, S.S. The effect of parity on uterine activity in labour. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1984, 91, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, E.A. Primigravid labor: A graphicostatistical analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1955, 6, 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, R.; Horiuchi, S.; Ohtsu, H. Evaluation of the labor curve in nulliparous Japanese women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, 226.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwal, E.; Livne, M.Y.; Benichou, J.I.C.; Unger, R.; Hiersch, L.; Aviram, A.; Mani, A.; Yogev, Y. Contemporary patterns of labor in nulliparous and multiparous women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 267.e1–267.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlass, F.E.; Duff, P. The duration of labor in primiparas undergoing vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 75, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Faranesh, R.; Salim, R. Labor progress among women attempting a trial of labor after cesarean. Do they have their own rules? Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2011, 90, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottenstreich, M.; Shahar, C.F.; Rotem, R.; Sela, H.Y.; Rottenstreich, A.; Samueloff, A.; Shen, O.; Reichman, O. Duration of first vaginal birth following cesarean: Is stage of labor at previous cesarean a factor? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 252, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusavy, Z.; Francova, E.; Paymova, L.; Ismail, K.M.; Kalis, V. Timing of cesarean and its impact on labor duration and genital tract trauma at the first subsequent vaginal birth: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primipara N = 13,983 | VBAC N = 736 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.71 (±4.2) | 32.6 (±3.6) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 (±3.6) | 26.9 (±3.9) | 0.118 |

| Height (cm) | 164.7 (±6.1) | 164.0 (±5.9) | 0.596 |

| Weight before pregnancy (kg) | 58.92 (±9.6) | 59.6 (±10.8) | 0.09 |

| Drugs Use | 110 (0.8%) | 8 (1.1%) | 0.377 |

| Smoking | 577 (4.1%) | 34 (4.6%) | 0.528 |

| Alcohol | 38 (0.27%) | 1 (0.13%) | 0.262 |

| Caucasian ethnicity | 13,303 (95.1%) | 713 (96.9%) | 0.163 |

| Asian ethnicity | 7 (1%) | 162 (1.2%) | 0.163 |

| African ethnicity | 294 (2.1%) | 10 (1.4%) | 0.163 |

| Primipara N = 13,983 | VBAC N = 736 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational Age (weeks) | 39.56 (±1.07) | 39.63 (±1.0) | 0.144 |

| Epidural Analgesia | 10,987 (78.6%) | 634 (86.1%) | <0.001 |

| Second Stage (min) | 86.6 (±59.9) | 77.8 (±57.5) | <0.001 |

| Prolonged Second Stage | 1324 (9.5%) | 52 (7.1%) | 0.029 |

| Cervical Dilatation Rate * (cm/h) | 2.85 (±3.35) | 3.261 (±4.91) | 0.011 |

| Intrapartum Fever | 120 (0.86%) | 7 (0.95%) | 0.791 |

| Episiotomy | 713 (5.10%) | 34 (4.70%) | 0.259 |

| OASI | 85 (0.61%) | 6 (0.81%) | 0.524 |

| Third Stage (min) | 15.4 (±10) | 15.1 (±9.6) | 0.386 |

| Hemoglobin Before Delivery (g/dL) | 12.4 (±1.2) | 12.4 (±1) | 0.837 |

| Hemoglobin After Delivery (g/dL) | 11.6 (±1.7) | 11.8 (±1.6) | 0.053 |

| Birthweight (g) | 3234 (±378) | 3266 (±367) | 0.025 |

| Male Gender | 6950 (49.70%) | 393 (53.40%) | 0.051 |

| OR for PSS | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VBAC | 0.541 | 0.388–0.753 | <0.001 |

| Maternal Age (years) | 1.055 | 1.039–1.071 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.996 | 0.979–1.012 | 0.61 |

| Cervical Dilatation Rate (cm/h) | 0.805 | 0.771–0.841 | <0.001 |

| Epidural Analgesia | 1.091 | 0.311–28.525 | 0.344 |

| Caucasian Ethnicity | 1.828 | 1.101–3.037 | 0.02 |

| Asian Ethnicity | 0.532 | 0.214–1.319 | 0.173 |

| African Ethnicity | 0.611 | 0.338–1.105 | 0.103 |

| Neonatal Birth Weight (per each 1 kg) | 1.88 | 1.602–2.204 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maor, M.; Attali, E.; Ashwal, E.; Dominsky, O.; Yogev, Y.; Baruch, Y. Effect of Previous Cesarean Section on Labor Progression: Comparison Between First VBAC and Primiparous Vaginal Deliveries. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8903. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248903

Maor M, Attali E, Ashwal E, Dominsky O, Yogev Y, Baruch Y. Effect of Previous Cesarean Section on Labor Progression: Comparison Between First VBAC and Primiparous Vaginal Deliveries. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8903. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248903

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaor, Maayan, Emmanuel Attali, Eran Ashwal, Omri Dominsky, Yariv Yogev, and Yoav Baruch. 2025. "Effect of Previous Cesarean Section on Labor Progression: Comparison Between First VBAC and Primiparous Vaginal Deliveries" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8903. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248903

APA StyleMaor, M., Attali, E., Ashwal, E., Dominsky, O., Yogev, Y., & Baruch, Y. (2025). Effect of Previous Cesarean Section on Labor Progression: Comparison Between First VBAC and Primiparous Vaginal Deliveries. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8903. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248903