Quantifying the Toll of Disuse: A Meta-Analysis of Skeletal Muscle Mass and Strength Loss Following Upper Limb Immobilization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategies

2.5. Study Selection Process

2.6. Data Collection Process and Data Items

2.7. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.8. Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

2.9. Effect Measures and Synthesis Methods

3. Results

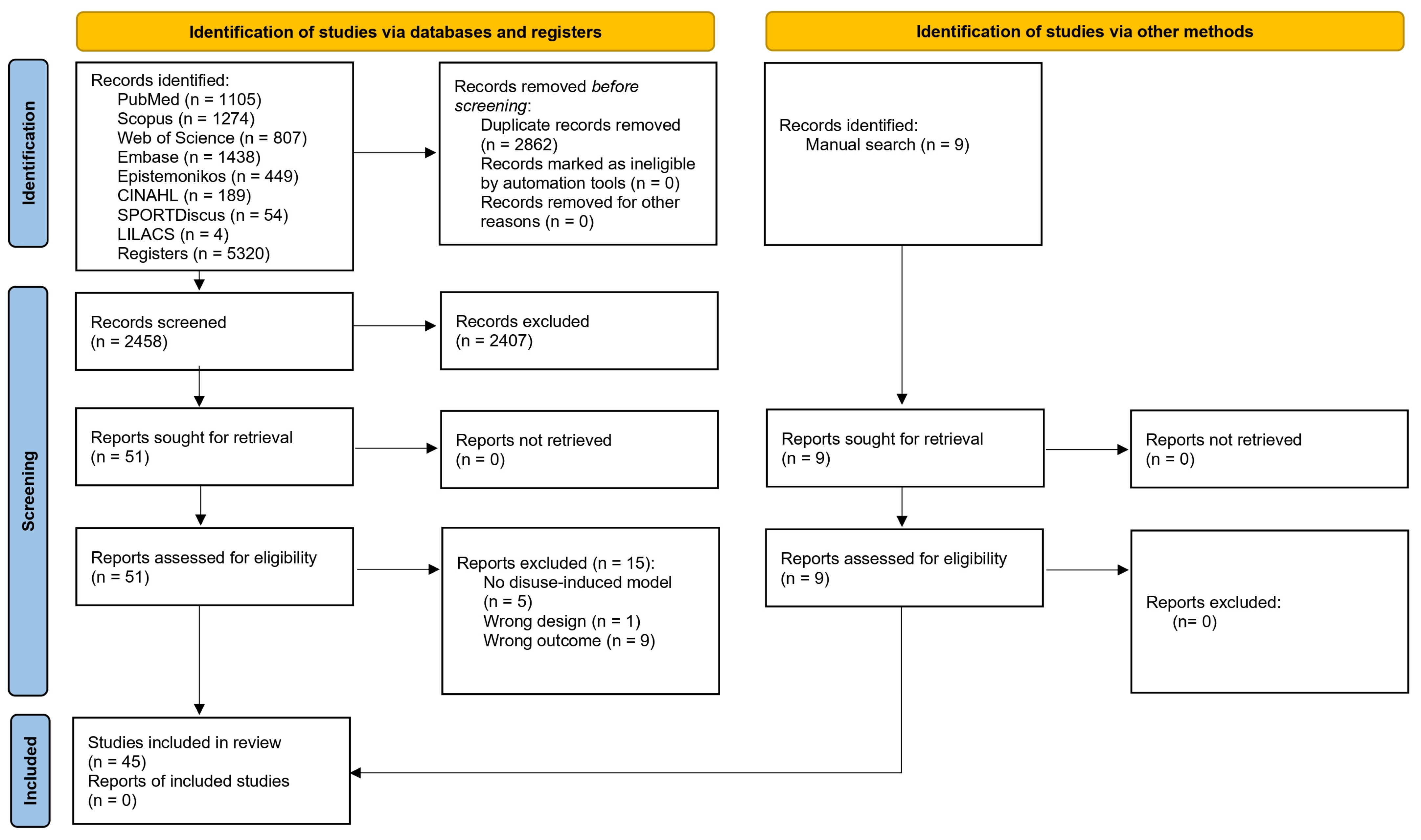

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

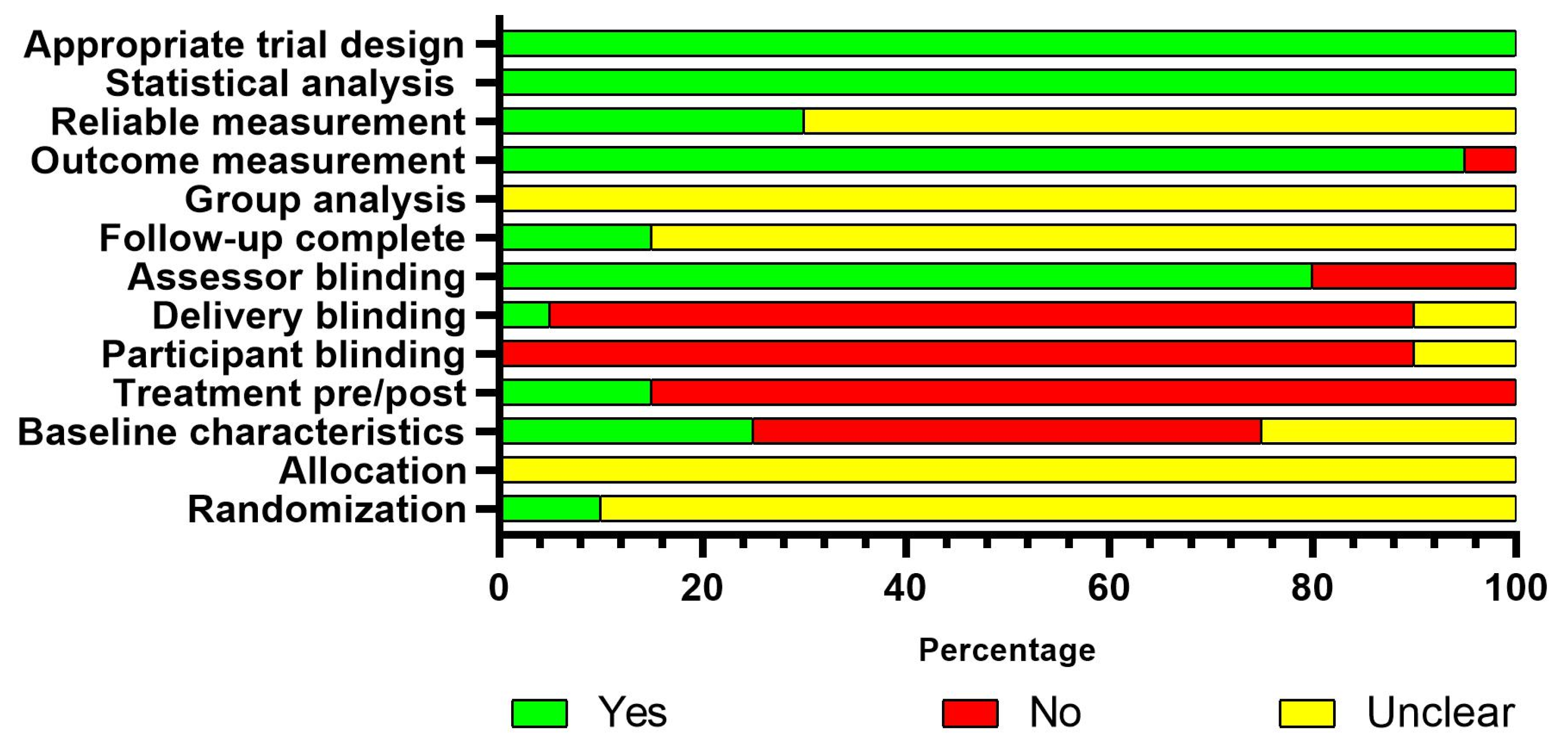

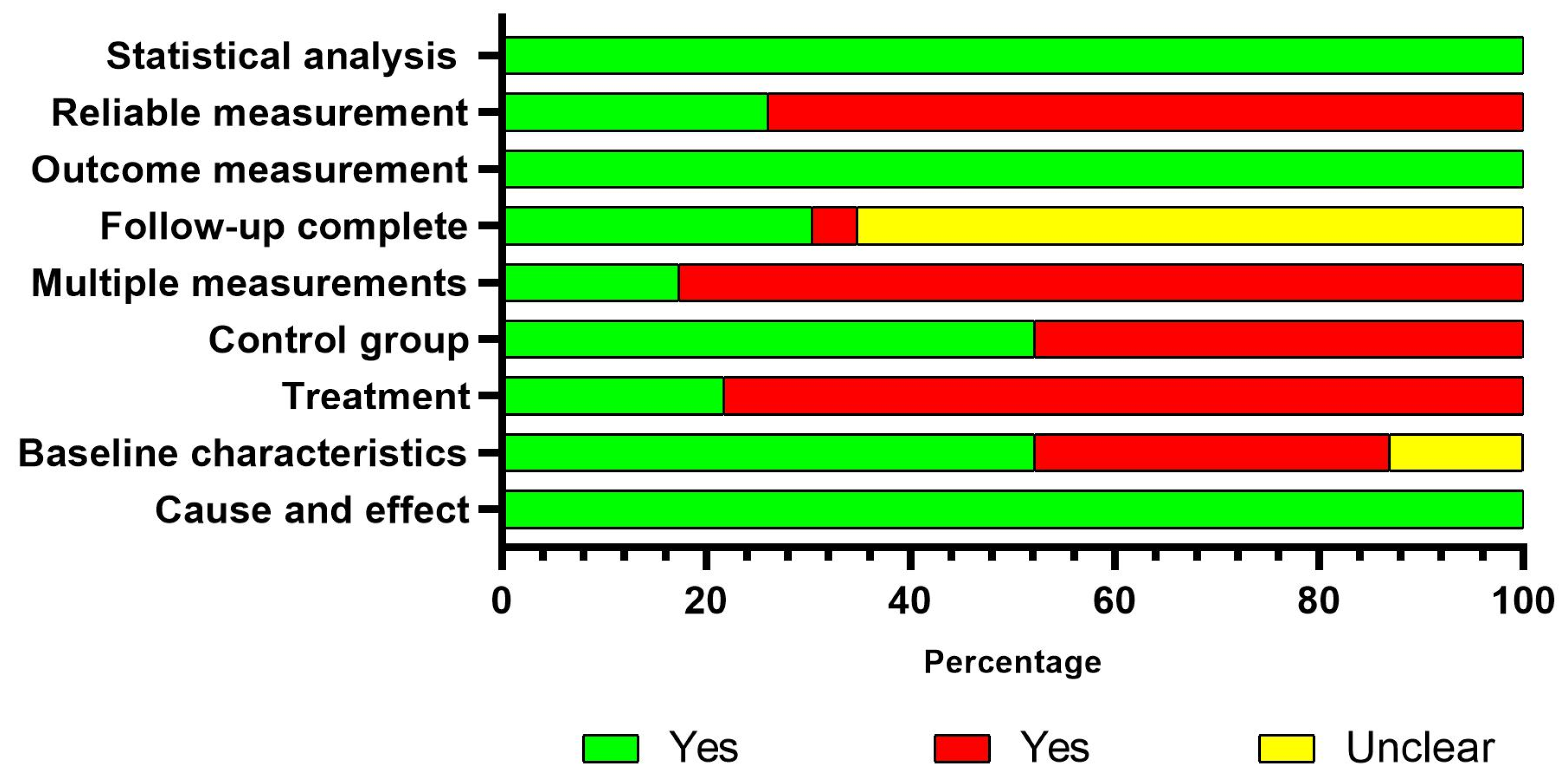

3.3. Risk of Bias

3.4. Synthesis of Results

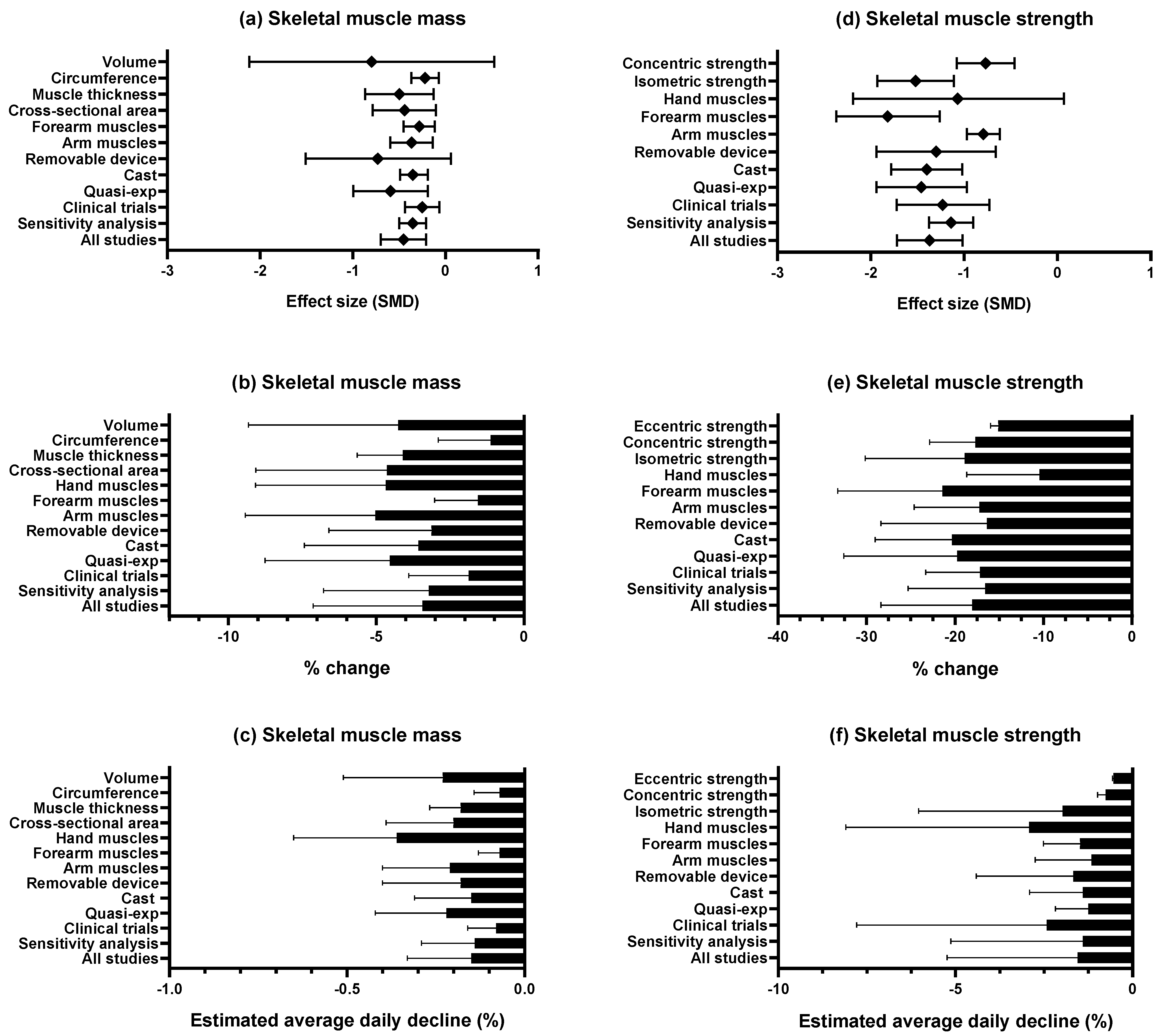

3.4.1. Skeletal Muscle Mass

3.4.2. Skeletal Muscle Strength

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1-RM | One-repetition maximum |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| DEXA | Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| MD | Mean difference |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| SMD | Standardized mean difference |

| Δtotal | Percentages of change in the pre–post-disuse-induced model |

| ↓daily | Estimated average daily decline |

References

- Wang, D.X.M.; Yao, J.; Zirek, Y.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Maier, A.B. Muscle Mass, Strength, and Physical Performance Predicting Activities of Daily Living: A Meta-Analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.-H.; Liao, Y.; Peng, Z.; Liu, F.; Wang, Q.; Yang, W. Association of Muscle Wasting with Mortality Risk among Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1596–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Bueno, R.; Andersen, L.L.; Koyanagi, A.; Núñez-Cortés, R.; Calatayud, J.; Casaña, J.; del Pozo Cruz, B. Thresholds of Handgrip Strength for All-Cause, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Mortality: A Systematic Review with Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 82, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, E.A.; Stokes, T.; McKendry, J.; Currier, B.S.; Phillips, S.M. Disuse-Induced Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Disease and Nondisease States in Humans: Mechanisms, Prevention, and Recovery Strategies. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2022, 322, C1068–C1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.H.U.; Chung, M.; Ren, Z.; Mair, D.B.; Kim, D.-H. Factors Mediating Spaceflight-Induced Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2022, 322, C567–C580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodine, S.C. Disuse-Induced Muscle Wasting. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 2200–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Varley-Campbell, J.; Fulford, J.; Taylor, B.; Mileva, K.N.; Bowtell, J.L. Effect of Immobilisation on Neuromuscular Function In Vivo in Humans: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 931–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preobrazenski, N.; Seigel, J.; Halliday, S.; Janssen, I.; McGlory, C. Single-Leg Disuse Decreases Skeletal Muscle Strength, Size, and Power in Uninjured Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.H.; Stone, J.C.; Sears, K.; Klugar, M.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. Revising the JBI Quantitative Critical Appraisal Tools to Improve Their Applicability: An Overview of Methods and the Development Process. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santesso, N.; Glenton, C.; Dahm, P.; Garner, P.; Akl, E.A.; Alper, B.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Carrasco-Labra, A.; De Beer, H.; Hultcrantz, M.; et al. GRADE Guidelines 26: Informative Statements to Communicate the Findings of Systematic Reviews of Interventions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 119, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Proyect Jamovi, Version 2.3; Jamovi Project: Sydney, Australia, 2023.

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IntHout, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Borm, G.F. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman Method for Random Effects Meta-Analysis Is Straightforward and Considerably Outperforms the Standard DerSimonian-Laird Method. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect Size Estimates: Current Use, Calculations, and Interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Egger, M.; Smith, G.D. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Investigating and Dealing with Publication and Other Biases in Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2001, 323, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, M.D.; Seynnes, O.R.; di Prampero, P.E.; Pisot, R.; Mekjavić, I.B.; Biolo, G.; Narici, M.V. Effect of 5 Weeks Horizontal Bed Rest on Human Muscle Thickness and Architecture of Weight Bearing and Non-Weight Bearing Muscles. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittweger, J.; Frost, H.; Schiessl, H.; Ohshima, H.; Alkner, B.; Tesch, P.; Felsenberg, D. Muscle Atrophy and Bone Loss after 90 Days’ Bed Rest and the Effects of Flywheel Resistive Exercise and Pamidronate: Results from the LTBR Study. Bone 2005, 36, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Nosaka, K.; Lin, J.-C. Effects of Immobilization and Active Mobilization on Recovery of Muscle after Eccentric Exercise. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2005, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Hope, P.; Newton, M.; Sacco, P.; Nosaka, K. Effects of Partial Immobilization after Eccentric Exercise on Recovery from Muscle Damage. J. Athl. Train. 2005, 40, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Andrushko, J.W.; Gould, L.A.; Farthing, J.P. Contralateral Effects of Unilateral Training: Sparing of Muscle Strength and Size after Immobilization. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostock, E.L.; Morse, C.I.; Winwood, K.; McEwan, I.M.; Onambélé-Pearson, G.L. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Vitamin D in Immobilisation: Part A—Modulation of Appendicular Mass Content, Composition and Structure. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostock, E.L.; Morse, C.I.; Winwood, K.; McEwan, I.M.; Onambélé-Pearson, G.L. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Vitamin D in Immobilisation: Part B—Modulation of Muscle Functional, Vascular and Activation Profiles. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.C.-C.; Kang, H.-Y.; Tseng, W.-C.; Lin, S.-C.; Chan, C.-W.; Chen, H.-L.; Chou, T.-Y.; Wang, H.-H.; Lau, W.Y.; Nosaka, K. Muscle Damage Induced by Maximal Eccentric Exercise of the Elbow Flexors after 3-Week Immobilization. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2023, 33, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.C.; Wu, S.-H.; Chen, H.-L.; Tseng, W.-C.; Tseng, K.-W.; Kang, H.-Y.; Nosaka, K. Effects of Unilateral Eccentric Versus Concentric Training of Non-Immobilized Arm During Immobilization. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2023, 55, 1195–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, B.C.; Mahato, N.K.; Nakazawa, M.; Law, T.D.; Thomas, J.S. The Power of the Mind: The Cortex as a Critical Determinant of Muscle Strength/Weakness. J. Neurophysiol. 2014, 112, 3219–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.C.; Hoffman, R.L.; Russ, D.W. Immobilization-Induced Increase in Fatigue Resistance Is Not Explained by Changes in the Muscle Metaboreflex. Muscle Nerve 2008, 38, 1466–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, B.C.; Manini, T.M.; Hoffman, R.L.; Russ, D.W. Restoration of Voluntary Muscle Strength after 3 Weeks of Cast Immobilization Is Suppressed in Women Compared with Men. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.C.; Taylor, J.L.; Hoffman, R.L.; Dearth, D.J.; Thomas, J.S. Cast Immobilization Increases Long-Interval Intracortical Inhibition. Muscle Nerve 2010, 42, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farthing, J.P.; Krentz, J.R.; Magnus, C.R.A. Strength Training the Free Limb Attenuates Strength Loss During Unilateral Immobilization. J Appl Physiol 2009, 106, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farthing, J.P.; Krentz, J.R.; Magnus, C.R.A.; Barss, T.S.; Lanovaz, J.L.; Cummine, J.; Esopenko, C.; Sarty, G.E.; Borowsky, R. Changes in Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Cortical Activation with Cross Education to an Immobilized Limb. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1394–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuglevand, A.J.; Bilodeau, M.; Enoka, R.M. Short-Term Immobilization Has a Minimal Effect on the Strength and Fatigability of a Human Hand Muscle. J Appl Physiol 1995, 78, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, C.J.; Drinkwater, A.; Joshi, S.D.; O’Hanlon, B.; Robinson, A.; Sands, K.-A.; Slade, K.; Braithwaite, J.J.; Nuttall, H.E. Short-Term Immobilization Promotes a Rapid Loss of Motor Evoked Potentials and Strength That Is Not Rescued by rTMS Treatment. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 640642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, T.; Hamaoka, T.; Murase, N.; Osada, T.; Murakami, M.; Kurosawa, Y.; Kitahara, A.; Ichimura, S.; Yashiro, K.; Katsumura, T. Low-Volume Muscle Endurance Training Prevents Decrease in Muscle Oxidative and Endurance Function During 21-Day Forearm Immobilization. Acta Physiol 2009, 197, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homma, T.; Hamaoka, T.; Osada, T.; Murase, N.; Kime, R.; Kurosawa, Y.; Ichimura, S.; Esaki, K.; Nakamura, F.; Katsumura, T. Once-Weekly Muscle Endurance and Strength Training Prevents Deterioration of Muscle Oxidative Function and Attenuates the Degree of Strength Decline During 3-Week Forearm Immobilization. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 115, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inada, T.; Kaneko, F.; Hayami, T. Effect of Kinesthetic Illusion Induced by Visual Stimulation on Muscular Output Function after Short-Term Immobilization. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2016, 27, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, A.P.W.; Burke, D.G.; MacNeil, L.G.; Candow, D.G. Effect of Creatine Supplementation During Cast-Induced Immobilization on the Preservation of Muscle Mass, Strength, and Endurance. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolczak, A.P.B.; Diefenthaeler, F.; Geremia, J.M.; Vaz, M.A. Two-Weeks of Elbow Immobilization Affects Torque Production but Does Not Change Muscle Activation. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2009, 13, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kitahara, A.; Hamaoka, T.; Murase, N.; Homma, T.; Kurosawa, Y.; Ueda, C.; Nagasawa, T.; Ichimura, S.; Motobe, M.; Yashiro, K.; et al. Deterioration of Muscle Function after 21-Day Forearm Immobilization. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1697–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundbye-Jensen, J.; Nielsen, J.B. Central Nervous Adaptations Following 1 Wk of Wrist and Hand Immobilization. J Appl Physiol 2008, 105, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, N.J.; Bhandari, M.; Blimkie, C.J.; Adachi, J.D.; Webber, C.E. Effect of Altered Physical Loading on Bone and Muscle in the Forearm. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2001, 79, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, C.R.A.; Barss, T.S.; Lanovaz, J.L.; Farthing, J.P. Effects of Cross-Education on the Muscle after a Period of Unilateral Limb Immobilization Using a Shoulder Sling and Swathe. J Appl Physiol 2010, 109, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, M.; Ueda, C.; Shiroishi, K.; Esaki, K.; Ohmori, F.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ichimura, S.; Kurosawa, Y.; Kime, R.; Osada, T.; et al. Low-Volume Muscular Endurance and Strength Training during 3-Week Forearm Immobilization Was Effective in Preventing Functional Deterioration. Dyn. Med. 2008, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.P.; Heil, D.P.; Larson, K.R.; Conant, S.B.; Schneider, S.M. Prior Resistance Training and Sex Influence Muscle Responses to Arm Suspension. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, 1983–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motobe, M.; Murase, N.; Osada, T.; Homma, T.; Ueda, C.; Nagasawa, T.; Kitahara, A.; Ichimura, S.; Kurosawa, Y.; Katsumura, T.; et al. Noninvasive Monitoring of Deterioration in Skeletal Muscle Function with Forearm Cast Immobilization and the Prevention of Deterioration. Dyn. Med. 2004, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsom, J.; Knight, P.; Balnave, R. Use of Mental Imagery to Limit Strength Loss after Immobilization. J. Sport. Rehabil. 2003, 12, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngomo, S.; Leonard, G.; Mercier, C. Influence of the Amount of Use on Hand Motor Cortex Representation: Effects of Immobilization and Motor Training. Neuroscience 2012, 220, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmori, F.; Hamaoka, T.; Shiroishi, K.; Osada, T.; Murase, N.; Kurosawa, Y.; Ichimura, S.; Homma, T.; Esaki, K.; Kime, R.; et al. Low-Volume Strength and Endurance Training Prevent the Decrease in Exercise Hyperemia Induced by Non-Dominant Forearm Immobilization. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 110, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parcell, A.C.; Trappe, S.W.; Godard, M.P.; Williamson, D.L.; Fink, W.J.; Costill, D.L. An Upper Arm Model for Simulated Weightlessness. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2000, 169, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, A.J.; Hendy, A.; Bowen, W.A.; Kidgell, D.J. Corticospinal Adaptations and Strength Maintenance in the Immobilized Arm Following 3 Weeks Unilateral Strength Training. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2013, 23, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers, S.P.; Clarkson, P.M.; Lee, J. Activity and Immobilization after Eccentric Exercise: I. Recovery of Muscle Function. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; Narusawa, M. Effects of Joint Immobilization on Firing Rate Modulation of Human Motor Units. J. Physiol. 2001, 530, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, K.; Kizuka, T.; Yamada, H. Reduction in Maximal Firing Rate of Motoneurons After 1-Week Immobilization of Finger Muscle in Human Subjects. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2007, 17, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semmler, J.G.; Kutzscher, D.V.; Enoka, R.M. Gender Differences in the Fatigability of Human Skeletal Muscle. J. Neurophysiol. 1999, 82, 3590–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa-Escalante, N.; Castro-Pérez, R.E.; Montero Herrera, B.; Jiménez-Díaz, J. Efecto de La Práctica Mental Kinestésica En La Fuerza y Actividad Mioeléctrica Del Bíceps Braquial, Luego de Un Periodo de Inmovilización de Codo En Adultos-Jóvenes Sanos. Ciencias de la actividad física 2022, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urso, M.L. Disuse Atrophy of Human Skeletal Muscle: Cell Signaling and Potential Interventions. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 1860–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdes, O.; Ramirez, C.; Perez, F.; Garcia-Vicencio, S.; Nosaka, K.; Penailillo, L. Contralateral Effects of Eccentric Resistance Training on Immobilized Arm. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, V.G. Effects of Upper Limb Immobilization on Isometric Muscle Strength, Movement Time, and Triphasic Electromyographic Characteristics. Phys. Ther. 1989, 69, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, G.; Bilodeau, M.; Hardy, P.; Enoka, R. Task-Dependent Effect of Limb Immobilization on the Fatigability of the Elbow Flexor Muscles in Humans. Exp. Physiol. 1997, 82, 567–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, M.S.; Bauerlein, H.M.; Edwards, M.F.; Stambaugh, K.E.; Parsowith, E.J.; Carr, J.C.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Richardson, R.M. Effects of Oral Contraceptives and Biological Sex on Grip Strength and Excitation During Immobilization and Recovery: An Exploratory Clinical Trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.C.; Voskuil, C.C.; Andrushko, J.W.; MacLennan, R.J.; DeFreitas, J.M.; Stock, M.S.; Farthing, J.P. Cross-Education Attenuates Muscle Weakness and Facilitates Strength Recovery after Orthopedic Immobilization in Females: A Pilot Study. Physiol. Rep. 2025, 13, e70329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, R.; Feng, Y.; Cheng, L. Molecular Mechanisms of Exercise Contributing to Tissue Regeneration. Sig Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughna, P.T.; Izumd, S.; Goldspink, G.; Nadal-Ginard, B. Disuse and Passive Stretch Cause Rapid Alterations in Expression of Developmental and Adult Contractile Protein Genes in Skeletal Muscle. Development 1990, 109, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Bruijn, S.M.; Daffertshofer, A. Overlap in the Cortical Representation of Hand and Forearm Muscles as Assessed by Navigated TMS. Neuroimage: Rep. 2023, 3, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, J.L. Using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation to Map the Cortical Representation of Lower-Limb Muscles. Clin. Neurophysiol. Pract. 2020, 5, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Arfat, Y.; Wang, H.; Goswami, N. Muscle Atrophy Induced by Mechanical Unloading: Mechanisms and Potential Countermeasures. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, M.D.; Selby, A.; Atherton, P.; Smith, K.; Seynnes, O.R.; Maganaris, C.N.; Maffulli, N.; Movin, T.; Narici, M.V.; Rennie, M.J. The Temporal Responses of Protein Synthesis, Gene Expression and Cell Signalling in Human Quadriceps Muscle and Patellar Tendon to Disuse. J. Physiol. 2007, 585, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.M.; Glover, E.I.; Rennie, M.J. Alterations of Protein Turnover Underlying Disuse Atrophy in Human Skeletal Muscle. J Appl Physiol 2009, 107, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, B.T.; Snijders, T.; Senden, J.M.G.; Ottenbros, C.L.P.; Gijsen, A.P.; Verdijk, L.B.; van Loon, L.J.C. Disuse Impairs the Muscle Protein Synthetic Response to Protein Ingestion in Healthy Men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 4872–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiaffino, S.; Mammucari, C. Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Growth by the IGF1-Akt/PKB Pathway: Insights from Genetic Models. Skelet. Muscle 2011, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrando, A.A.; Stuart, C.A.; Sheffield-Moore, M.; Wolfe, R.R. Inactivity Amplifies the Catabolic Response of Skeletal Muscle to Cortisol. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 3515–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, B.T.; Dirks, M.L.; Snijders, T.; van Dijk, J.-W.; Fritsch, M.; Verdijk, L.B.; van Loon, L.J.C. Short-Term Muscle Disuse Lowers Myofibrillar Protein Synthesis Rates and Induces Anabolic Resistance to Protein Ingestion. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 310, E137–E147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marusic, U.; Narici, M.; Simunic, B.; Pisot, R.; Ritzmann, R. Nonuniform Loss of Muscle Strength and Atrophy during Bed Rest: A Systematic Review. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 131, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, R.K.A.; Hibbert, J.E.; Jorgenson, K.W.; Hornberger, T.A. The Structural Adaptations That Mediate Disuse-Induced Atrophy of Skeletal Muscle. Cells 2023, 12, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, A.F.; Brioche, T.; Arc-Chagnaud, C.; Demangel, R.; Chopard, A.; Py, G. Short-Term Disuse Promotes Fatty Acid Infiltration into Skeletal Muscle. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biltz, N.K.; Collins, K.H.; Shen, K.C.; Schwartz, K.; Harris, C.A.; Meyer, G.A. Infiltration of Intramuscular Adipose Tissue Impairs Skeletal Muscle Contraction. J. Physiol. 2020, 598, 2669–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brocca, L.; Longa, E.; Cannavino, J.; Seynnes, O.; de Vito, G.; McPhee, J.; Narici, M.; Pellegrino, M.A.; Bottinelli, R. Human Skeletal Muscle Fibre Contractile Properties and Proteomic Profile: Adaptations to 3 Weeks of Unilateral Lower Limb Suspension and Active Recovery. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 5361–5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirago, G.; Pellegrino, M.A.; Bottinelli, R.; Franchi, M.V.; Narici, M.V. Loss of Neuromuscular Junction Integrity and Muscle Atrophy in Skeletal Muscle Disuse. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 83, 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shur, N.F.; Simpson, E.J.; Crossland, H.; Constantin, D.; Cordon, S.M.; Constantin-Teodosiu, D.; Stephens, F.B.; Brook, M.S.; Atherton, P.J.; Smith, K.; et al. Bed-Rest and Exercise Remobilization: Concurrent Adaptations in Muscle Glucose and Protein Metabolism. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burd, N.A.; Gorissen, S.H.; van Loon, L.J.C. Anabolic Resistance of Muscle Protein Synthesis with Aging. Exerc. Sport. Sci. Rev. 2013, 41, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsiopoulos, N.; Baumgartner, R.N.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Lyons, W.; Gallagher, D.; Ross, R. Cadaver Validation of Skeletal Muscle Measurement by Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computerized Tomography. J Appl Physiol 1998, 85, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruse, M.; Trappe, S.; Trappe, T.A. Human Skeletal Muscle Size with Ultrasound Imaging: A Comprehensive Review. J Appl Physiol 2022, 132, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, R.E.; Brunker, L.B.; Agergaard, J.; Barrows, K.M.; Briggs, R.A.; Kwon, O.S.; Young, L.M.; Hopkins, P.N.; Volpi, E.; Marcus, R.L.; et al. Age-Related Differences in Lean Mass, Protein Synthesis and Skeletal Muscle Markers of Proteolysis after Bed Rest and Exercise Rehabilitation. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 4259–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappe, T. Influence of Aging and Long-Term Unloading on the Structure and Function of Human Skeletal Muscle. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 34, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, N.; Glover, E.I.; Phillips, S.M.; Isfort, R.J.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Sex-Based Differences in Skeletal Muscle Function and Morphology with Short-Term Limb Immobilization. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 99, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hvid, L.G.; Suetta, C.; Nielsen, J.H.; Jensen, M.M.; Frandsen, U.; Ørtenblad, N.; Kjaer, M.; Aagaard, P. Aging Impairs the Recovery in Mechanical Muscle Function Following 4 Days of Disuse. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, D.; Messina, C.; Vitale, J.; Sconfienza, L.M. Imaging of Sarcopenia: Old Evidence and New Insights. Eur. Radiol. 2020, 30, 2199–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mijnarends, D.M.; Meijers, J.M.M.; Halfens, R.J.G.; ter Borg, S.; Luiking, Y.C.; Verlaan, S.; Schoberer, D.; Cruz Jentoft, A.J.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Schols, J.M.G.A. Validity and Reliability of Tools to Measure Muscle Mass, Strength, and Physical Performance in Community-Dwelling Older People: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Year | Body Part | Design | Characteristics of the Participants | Characteristics of Disuse-Induced Models | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | IG n | Age (years) | M | F | PA or Training Experience | Device | Limb Immobilized | Time (days) | Daily Time Use (hours) | Remove Device | Joint Immobilized | Angle Joint Position | |||

| Bostock et al., 2017a [24] | Arm | RCT | 24 | 8 | 26 ± 6.7 | 2 | 6 | Recreationally active | Sling | Nondominant | 14 | 9 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Bostock et al., 2017b [25] | Arm | RCT | 24 | 8 | 26 ± 6.7 | 2 | 6 | Recreationally active | Sling | Nondominant | 14 | 9 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Boer et al., 2008 [19] | Arm | CES | 10 | 10 | 22 ± 2.2 | 10 | 0 | NR | Bed rest | NA | 35 | 24 | NA | NA | NA |

| Chen et al., 2005 [21] | Arm | RCT | 33 | 11 | 21 ± 3.1 | 11 | 0 | Physically active | Cast | Nondominant | 4 | 24 | NO | Shoulder and elbow | NR |

| Chen et al., 2023 [26] | Arm | CES | 24 | 12 | 23 ± 2.1 | 12 | 0 | Sedentary | Cast + sling | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Chen et al., 2023 [27] | Arm | CES | 36 | 12 | 22.7 + 1.7 | 12 | 0 | Sedentary | Cast + sling | Nondominant | 14 | 24 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Gaffney et al., 2021 [35] | Arm and forearm | RCT | 24 | 12 | 21 ± 0.6 | 12 | 0 | Recreationally active | Sling + swathe | Dominant | 3 | 24 | NO | Shoulder, elbow, and wrist | NR |

| Johnston et al., 2009 [39] | Arm | Crossover | 7 | 7 | 22 | 7 | 0 | NR | Plaster Cast | Randomized | 7 | 24 | NO | Elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Karolczak et al., 2009 [40] | Arm | CES | 18 | 7 | 30 ± 7.6 | 7 | 0 | NR | Plaster Cast | Nondominant | 14 | 24 | NO | Elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Magnus et al., 2010 [44] | Arm | CES | 25 | 8 | 20 ± 1.8 | 2 | 6 | 2.0 ± 3.9 months | Sling + swathe | Nondominant | 28 | 13 | Sling + swathe | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Miles et al., 2005 [46] | Arm | CES | 31 | 16 | 21 ± 3 | 6 | 10 | NR | Sling + swathe | Nondominant | 21 | 16 | Sling + swathe | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Parcell et al., 2000 [51] | Arm | CES | 6 | 6 | 23 ± 1 | 6 | 0 | Normo-active | Sling | Nondominant | 28 | 16 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Pearce et al., 2013 [52] | Arm | RCT | 28 | 9 | 25 ± 8.7 | 4 | 5 | NR | Sling | Nondominant | 21 | 15 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Sayers et al., 2000a [53] | Arm | RCT | 26 | 9 | 20 ± 0.4 | 9 | 0 | NR | Cast + sling | Nondominant | 4 | 24 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Semmler et al., 1999 [56] | Arm | CES | 16 | 12 | 18–45 | 6 | 6 | NR | Cast + sling | Nondominant | 28 | 24 | Sling | Shoulder, elbow, and wrist | NR |

| Valdes et al., 2021 [59] | Arm | RCT | 30 | 10 | 23 ± 5.0 | 6 | 4 | NR | Sling | Nondominant | 28 | 8 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Vaughan, 1989 [60] | Arm | CES | 6 | 6 | 31.2 | 4 | 2 | NR | Plaster Cast + sling | Nondominant | 14 | 24 | Sling | Shoulder, elbow, and wrist | 90° elbow flexion |

| Yue et al., 1997 [61] | Arm | CES | 10 | 10 | 19–27 | NR | NR | NR | Cast + sling | Nondominant | 28 | 24 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Zainuddin et al., 2005 [22] | Arm | CE | 10 | 10 | 23 ± 4.2 | 5 | 5 | NR | Splint + sling | Randomized | 4 | 16 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Andrushko et al., 2018 [23] | Forearm | RCT | 16 | 8 | 23 ± 5 | 2 | 6 | 2.9 ± 4.3 months | Cast | Nondominant | 28 | 24 | NO | Wrist, thumb, and proximal interphalangeal joints | Wrist in neutral position |

| Clark et al., 2014 [28] | Forearm | CES | 29 | 15 | 21 ± 3.5 | 8 | 7 | NR | Splint + sling | Nondominant | 28 | 24 | Sling | Wrist and fingers | Wrist in neutral position |

| Clark et al., 2008 [29] | Forearm | CES | 19 | 10 | 21 ± 0.5 | 5 | 5 | NR | Splint | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | Sling | Wrist and fingers | Wrist in neutral position |

| Clark et al., 2009 [30] | Forearm | CES | 10 | 10 | 18–29 | 5 | 5 | NR | Splint | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | NR | Wrist and hand | Wrist in neutral position |

| Clark et al., 2010 [31] | Forearm | CES | 20 | 11 | 20 ± 0.4 | 6 | 5 | NR | Splint | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | Splint | Wrist and fingers | NR |

| Farthing et al., 2009 [32] | Forearm | CES | 30 | 10 | 22 ± 2.8 | 2 | 8 | 2.5 ± 3.9 months | Cast | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | NO | Wrist, thumb, and proximal interphalangeal joints | Wrist in neutral position |

| Farthing et al., 2011 [33] | Forearm | CES | 14 | 7 | 22 ± 4.4 | 1 | 6 | 3.9 ± 1.6 months | Cast | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | NO | Wrist, thumb, and proximal interphalangeal joints | Wrist in neutral position |

| Homma et al., 2009 [36] | Forearm | RCT | 15 | 7 | 20–29 | 7 | 0 | NR | Cast + sling | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | Sling | Elbow and wrist | 90° elbow flexion |

| Homma et al., 2015 [37] | Forearm | RCT | 34 | 7 | 22 ± 3.0 | 7 | 0 | NR | Cast + sling | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | Sling | Elbow and wrist | 90° elbow flexion |

| Kitahara et al., 2003 [41] | Forearm | CES | 6 | 6 | 21 ± 1.4 | 6 | 0 | Physically active | Cast + sling | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | Sling | Elbow and wrist | NR |

| Lundbye-Jensen-Nielsen et al., 2008 [42] | Forearm | CES | 10 | 10 | 24 ± 6 | 6 | 4 | NR | Cast | Nondominant | 7 | 24 | NO | Wrist and fingers | Wrist in neutral position |

| MacIntyre et al., 2001 [43] | Forearm | RCT | 9 | 9 | 24 ± 44 | NR | NR | Sedentary | Plaster Cast | Nondominant | 42 | 24 | NO | Wrist | NR |

| Matsumura et al., 2008 [45] | Forearm | RCT | 10 | 5 | 23 ± 3.3 | 5 | 0 | NR | Cast + sling | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | Sling | Elbow, wrist, and fingers | NR |

| Motobe et al., 2004 [47] | Forearm | RCT | 14 | 8 | 23 ± 2.6 | 8 | 0 | NR | Cast | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | NO | Elbow, wrist, and fingers | NR |

| Newsom et al., 2003 [48] | Forearm | RCT | 18 | 8 | 13–30 | 0 | 8 | NR | Cast | Nondominant | 10 | 24 | NO | Wrist | Wrist in 15–30° extension |

| Ohmori et al., 2010 [50] | Forearm | RCT | 21 | 7 | 22 ± 2.9 | 7 | 0 | NR | Cast + sling | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | Sling | Elbow, wrist, and fingers | NR |

| Ulloa-Escalante et al., 2022 [57] | Forearm | RCT | 14 | 7 | 18 ± 0.9 | NR | NR | NR | Sling | Nondominant | 6 | 16 | Sling | Shoulder and elbow | NR |

| Rittweger et al., 2005 [20] | Forearm | RCT | 25 | 9 | 32 ± 4.2 | 9 | 0 | 19.3 ± 10.3 Freiburg Questionnaire | Bed rest | NA | 90 | 24 | NA | NA | NA |

| Fuglevand et al., 1995 [34] | Fingers | CES | 11 | 11 | 24–45 | 8 | 3 | NR | Splint | Nondominant | 21 | 24 | Splint | Thumb and index finger | Flexed position |

| Inada et al., 2015 [38] | Fingers | RCT | 30 | 10 | 29 ± 4.2 | 10 | 0 | NR | Elastic bandage + sling | Nondominant | 0.5 | 12 | Sling | All fingers | Fingers extended; thumb adducted. |

| Ngomo et al., 2012 [49] | Fingers | Crossover | 11 | 11 | 26 ± 4.3 | NR | NR | NR | Splint | Nondominant | 4 | 24 | NO | Wrist and fingers | NR |

| Seki et al., 2001 [54] | Fingers | CES | 7 | 7 | 21–22 | 7 | 0 | NR | Cast | Nondominant | 42 | 24 | CAST | Middle and index finger and thumb | Index flexed 30–40° |

| Seki et al., 2007 [55] | Fingers | CES | 5 | 5 | 22–29 | 5 | 0 | NR | Cast | Nondominant | 7 | 24 | NR | Middle and index finger and thumb | Index flexed 30–40° |

| Urso et al., 2006 [58] | Fingers | CES | 28 | 28 | 66 ± 1 20 ± 0.6 | 20 | 0 | NR | Brace | Nondominant | 14 | 24 | NR | Thumb | NR |

| Stock et al., 2025 [62] | Forearm | CES | 30 | 20 | 22 ± 3.0 | 10 | 10 | High-moderate activity | Splint | Non-dominant | 7 | 24 | NR | Wrist, thumb, and fingers | NR |

| Carr et al., 2025 [63] | Arm | RCT | 10 | 4 | 19 ± 0.5 | 0 | 4 | NR | Sling + swathe | Non-dominant | 28 | 10 | Sling + swathe | Shoulder and elbow | 90° elbow flexion |

| Groups | Subgroup | % Change | Meta-Analysis | Heterogeneity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per Model | Per Day | N Data | Effect Size Model | Intercept | SE | CI 95% | p | I2 (%) | p | ||

| Design | RCT | −1.87 | −0.08 | 12 | RE-SMD | −0.25 | 0.08 | −0.44 to −0.07 | 0.013 | 7.78 | 0.975 |

| Quasi-exp. | −4.54 | −0.22 | 17 | RE-SMD | −0.59 | 0.19 | −0.99 to −0.19 | 0.007 | 61.9 | <0.001 | |

| Device | Cast | −3.57 | −0.15 | 20 | RE-SMD | −0.35 | 0.07 | −0.49 to −0.19 | <0.001 | 0 | 0.991 |

| Removable | −3.13 | −0.18 | 9 | RE-SMD | −0.73 | 0.34 | −1.51 to 0.06 | 0.067 | 78.9 | <0.001 | |

| Body part | Arm | −5.03 | −0.21 | 13 | RE-SMD | −0.37 | 0.11 | −0.59 to −0.14 | 0.005 | 19.3 | 0.800 |

| Forearm | −1.56 | −0.07 | 13 | RE-SMD | −0.28 | 0.08 | −0.45 to −0.11 | 0.003 | 5.6 | 0.991 | |

| Hand | −4.67 | −0.36 | 2 * | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Outcome | CSA (cm2) | −4.64 | −0.20 | 9 | FE-MD | −0.89 | 0.25 | −1.38 to −0.39 | <0.001 | 0 | 0.931 |

| MT (cm) | −4.10 | −0.18 | 5 | FE-MD | −0.13 | 0.02 | −0.19 to −0.06 | 0.005 | 0 | 0.924 | |

| CIR (cm) | −1.13 | −0.07 | 9 | FE-MD | −0.15 | 0.05 | −0.27 to −0.04 | 0.017 | 0 | 0.989 | |

| VOL (cm3) | −4.26 | −0.23 | 6 | FE-MD | −0.96 | 0.09 | −1.15 to −0.77 | <0.001 | 62.7 | 0.020 | |

| Muscle | BB+B | −5.77 | −0.23 | 6 | RE-SMD | −0.36 | 0.16 | −0.76 to 0.04 | 0.007 | 17.6 | 0.690 |

| WF | −3.62 | −0.16 | 3 | RE-SMD | −0.59 | 0.21 | −1.51 to 0.34 | 0.112 | 12.3 | 0.580 | |

| Disuse days | ≤10 days | −0.44 | −0.09 | 3 | RE-SMD | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.28 to 0.12 | 0.236 | 0.05 | 0.969 |

| 21 days | −2.69 | −0.13 | 15 | RE-SMD | −0.43 | 0.10 | −0.65 to −0.21 | <0.001 | 17.9 | 0.852 | |

| 28 days | −5.08 | −0.18 | 9 | RE-SMD | −0.24 | 0.06 | −0.37 to −0.10 | 0.003 | 1.3 | 0.999 | |

| Groups | Subgroup | % Change | Meta-Analysis | Heterogeneity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per Model | Per Day | N Data | Effect Size Model | Intercept | SE | CI 95% | p | I2 (%) | p | ||

| Design | RCT | −17.17 | −2.42 | 24 | RE-SMD | −1.23 | 0.24 | −1.72 to −0.73 | <0.001 | 81.2 | <0.001 |

| Quasi-exp. | −19.76 | −1.25 | 31 | RE-SMD | −1.46 | 0.24 | −1.94 to −0.97 | <0.001 | 83.9 | <0.001 | |

| Device | Cast | −20.35 | −1.40 | 31 | RE-SMD | −1.40 | 0.19 | −1.78 to −1.02 | <0.001 | 74.8 | <0.001 |

| Removable | −16.41 | −1.67 | 24 | RE-SMD | −1.30 | 0.31 | −1.94 to −0.66 | <0.001 | 88.5 | <0.001 | |

| Body part | Arm | −17.25 | −1.16 | 20 | RE-SMD | −0.79 | 0.08 | −0.97 to −0.61 | <0.001 | 16.7 | 0.941 |

| Forearm | −21.42 | −1.48 | 27 | RE-SMD | −1.82 | 0.19 | −2.37 to −1.26 | <0.001 | 83.76 | <0.001 | |

| Hand | −10.46 | −2.92 | 6 | RE-SMD | −1.07 | 0.45 | −2.19 to 0.07 | 0.061 | 78.3 | <0.001 | |

| Outcome | Iso | −18.9 | −1.97 | 45 | RE-SMD | −1.52 | 0.20 | −1.93 to −1.12 | <0.001 | 84.3 | <0.001 |

| Con | −17.70 | −0.76 | 8 | RE-SMD | −0.77 | 0.13 | −1.08 to −0.46 | <0.001 | 15.9 | 0.773 | |

| Ecc | −15.09 | −0.54 | 2 * | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Muscle or action | EE | −14.60 | −0.76 | 6 | RE-SMD | −0.66 | 0.19 | −1.14 to −0.18 | 0.017 | 26.1 | 0.594 |

| EF | −18.31 | −1.32 | 13 | RE-SMD | −1.11 | 0.33 | −1.81 to −0.39 | 0.005 | 82.9 | 0.010 | |

| WE | −19.06 | −1.55 | 5 | RE-SMD | −1.11 | 0.32 | −1.99 to −0.23 | 0.025 | 51.2 | 0.141 | |

| WF | −28.73 | −1.64 | 8 | RE-SMD | −2.21 | 0.82 | −4.15 to −0.27 | 0.031 | 93.7 | <0.001 | |

| FDI | −12.29 | −4.14 | 4 | RE-SMD | −0.42 | 0.20 | −1.06 to 0.20 | 0.121 | 13.9 | 0.587 | |

| HG | −15.69 | −1.43 | 13 | RE-SMD | −1.65 | 0.27 | −2.23 to −1.06 | <0.001 | 68.3 | <0.001 | |

| Disuse days | ≤10 days | −20.18 | −5.18 | 9 | RE-SMD | −1.75 | 0.52 | −2.95 to −0.54 | 0.010 | 88.7 | <0.001 |

| 14 days | −11.93 | −0.85 | 8 | RE-SMD | −1.04 | 0.35 | −1.87 to −0.21 | 0.021 | 71.01 | <0.001 | |

| 21 days | −17.11 | −0.81 | 20 | RE-SMD | −1.54 | 0.25 | −2.05 to −1.02 | <0.001 | 77.13 | <0.001 | |

| 28 days | −21.95 | −0.78 | 12 | RE-SMD | −1.08 | 0.47 | −2.11 to −0.06 | <0.040 | 90.06 | <0.001 | |

| >28 days | −23.00 | −0.76 | 3 | RE-SMD | −1.61 | 0.83 | −5.19 to 1.96 | 0.192 | 82.9 | <0.008 | |

| Characteristic | Disuse-Induced Model * | |

|---|---|---|

| Arm Muscles | Forearm Muscles | |

| Immobilizer device | For skeletal muscle mass only cast plus sling; for skeletal muscle strength removable device (sling) or cast. | For skeletal muscle mass only cast plus sling; for skeletal muscle strength removable device (splint, brace, bandage) or cast. |

| Joint immobilized | Shoulder and elbow. | Elbow and wrist; wrist and fingers. |

| Joint position | 90° elbow flexion. | Wrist in neutral position. |

| Time model | For skeletal muscle mass: 21 days. For skeletal muscle strength: <10 to 14 days. | |

| Daily time used | Cast 24 h. Sling 16–15 h. | |

| Device removal | Sling removal for sleeping or bathing. | |

| Instructions | During the study, avoid using the upper limb to lift, push, pull, or hold objects, lifting weight, performing vigorous physical activity, or driving a car. It is optional to instruct the participant to consider the limb injured. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuyul-Vásquez, I.; Ponce-Fuentes, F.; Salazar-Méndez, J.; Sepúlveda-Lara, A.; Suso-Martí, L.; Marzuca-Nassr, G.N.; Lluch, E.; Calatayud, J. Quantifying the Toll of Disuse: A Meta-Analysis of Skeletal Muscle Mass and Strength Loss Following Upper Limb Immobilization. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8884. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248884

Cuyul-Vásquez I, Ponce-Fuentes F, Salazar-Méndez J, Sepúlveda-Lara A, Suso-Martí L, Marzuca-Nassr GN, Lluch E, Calatayud J. Quantifying the Toll of Disuse: A Meta-Analysis of Skeletal Muscle Mass and Strength Loss Following Upper Limb Immobilization. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8884. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248884

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuyul-Vásquez, Iván, Felipe Ponce-Fuentes, Joaquín Salazar-Méndez, Alexis Sepúlveda-Lara, Luis Suso-Martí, Gabriel Nasri Marzuca-Nassr, Enrique Lluch, and Joaquín Calatayud. 2025. "Quantifying the Toll of Disuse: A Meta-Analysis of Skeletal Muscle Mass and Strength Loss Following Upper Limb Immobilization" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8884. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248884

APA StyleCuyul-Vásquez, I., Ponce-Fuentes, F., Salazar-Méndez, J., Sepúlveda-Lara, A., Suso-Martí, L., Marzuca-Nassr, G. N., Lluch, E., & Calatayud, J. (2025). Quantifying the Toll of Disuse: A Meta-Analysis of Skeletal Muscle Mass and Strength Loss Following Upper Limb Immobilization. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8884. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248884