The Role of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Children with Cystic Fibrosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

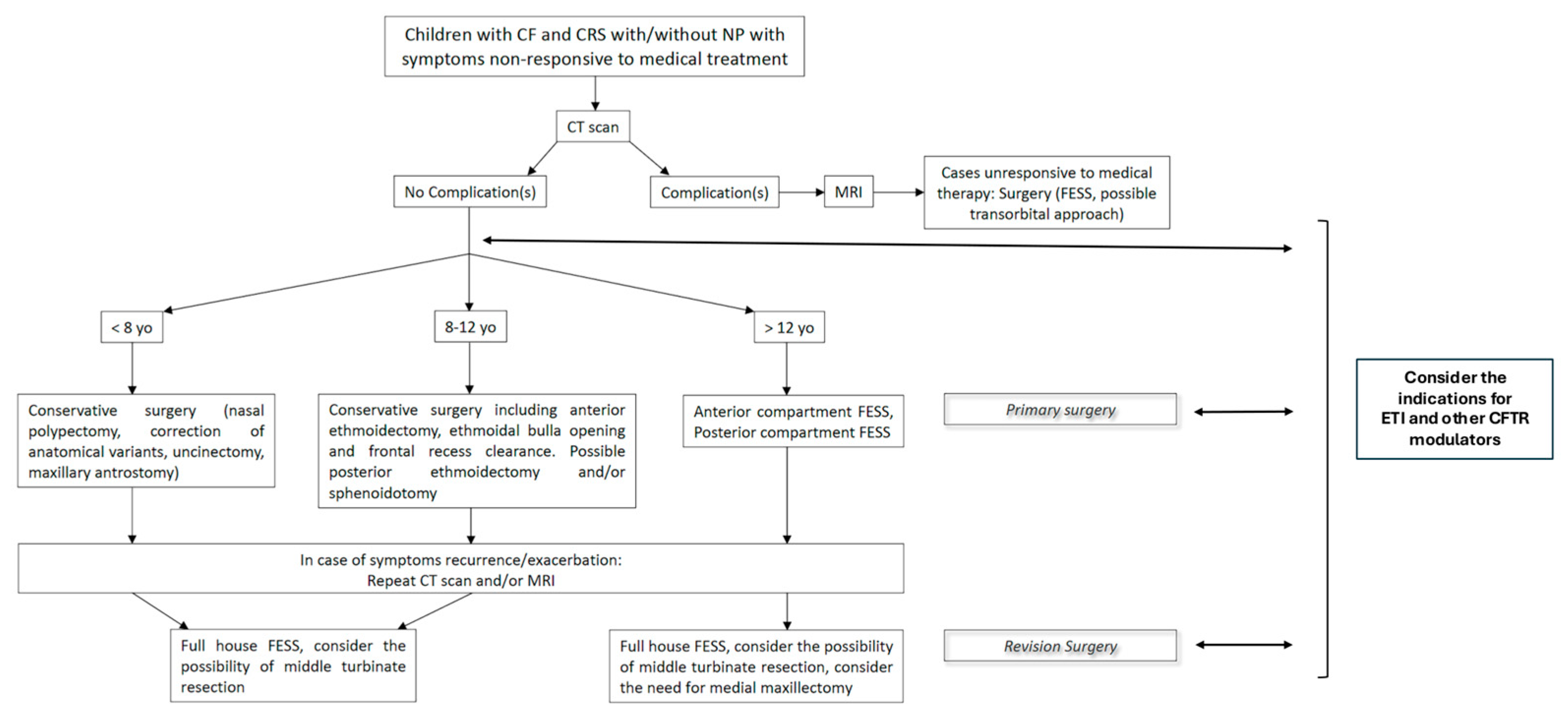

3.1. Diagnostic Findings

3.1.1. Symptoms

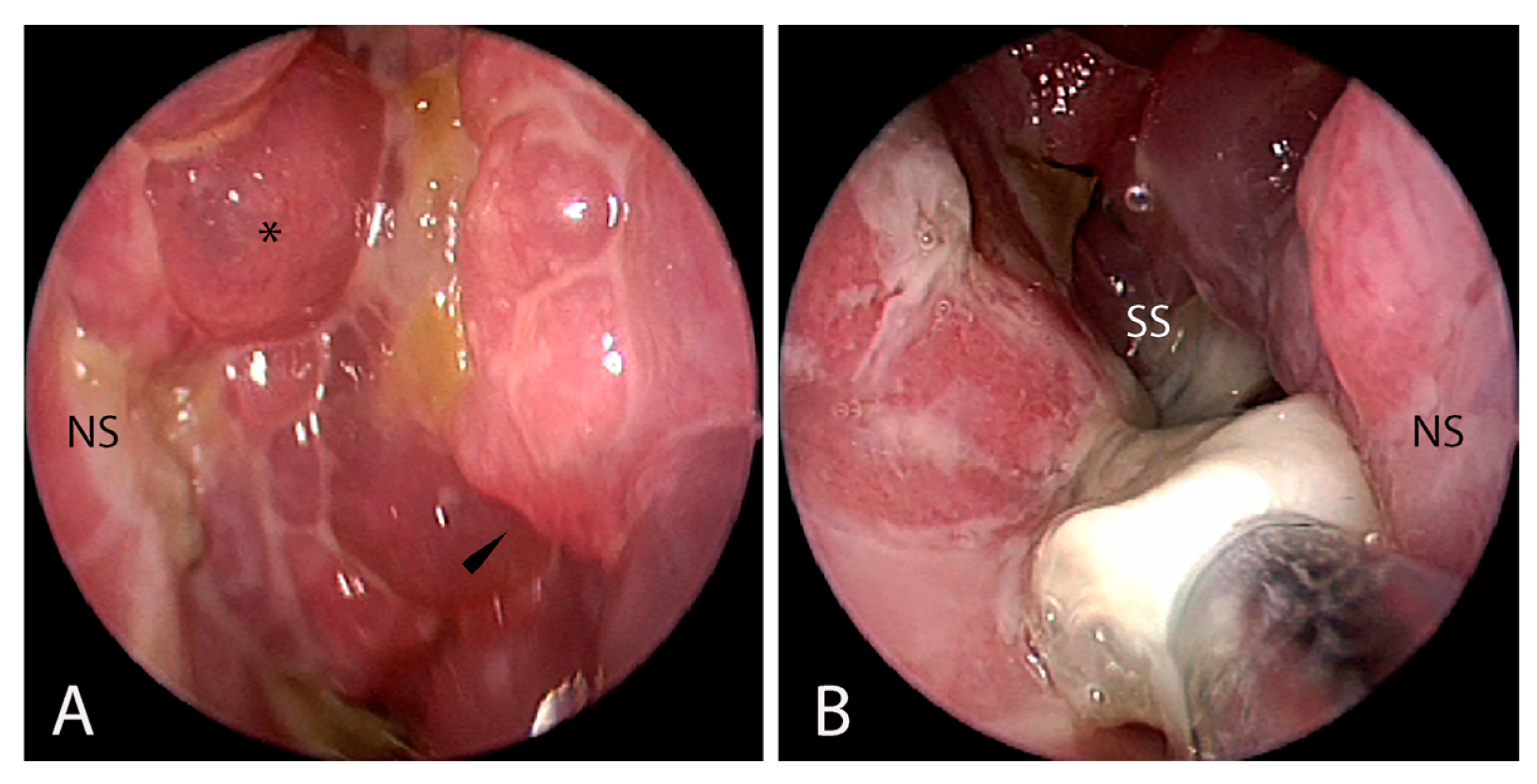

3.1.2. Endoscopic Findings

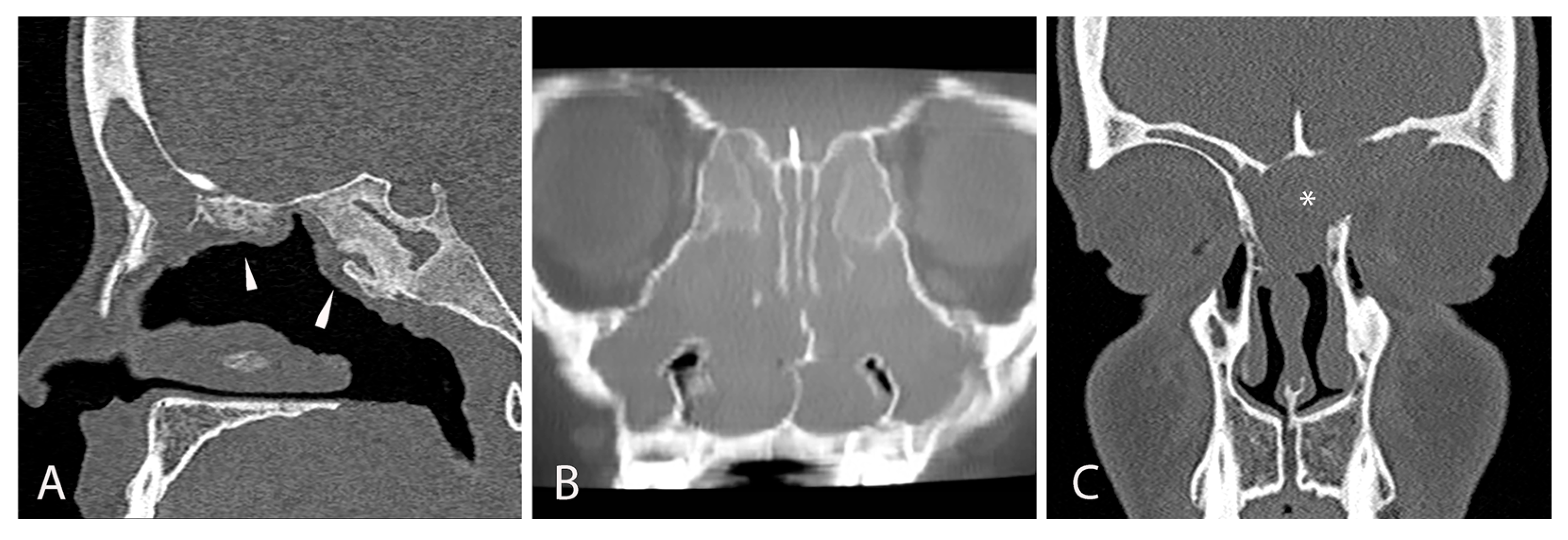

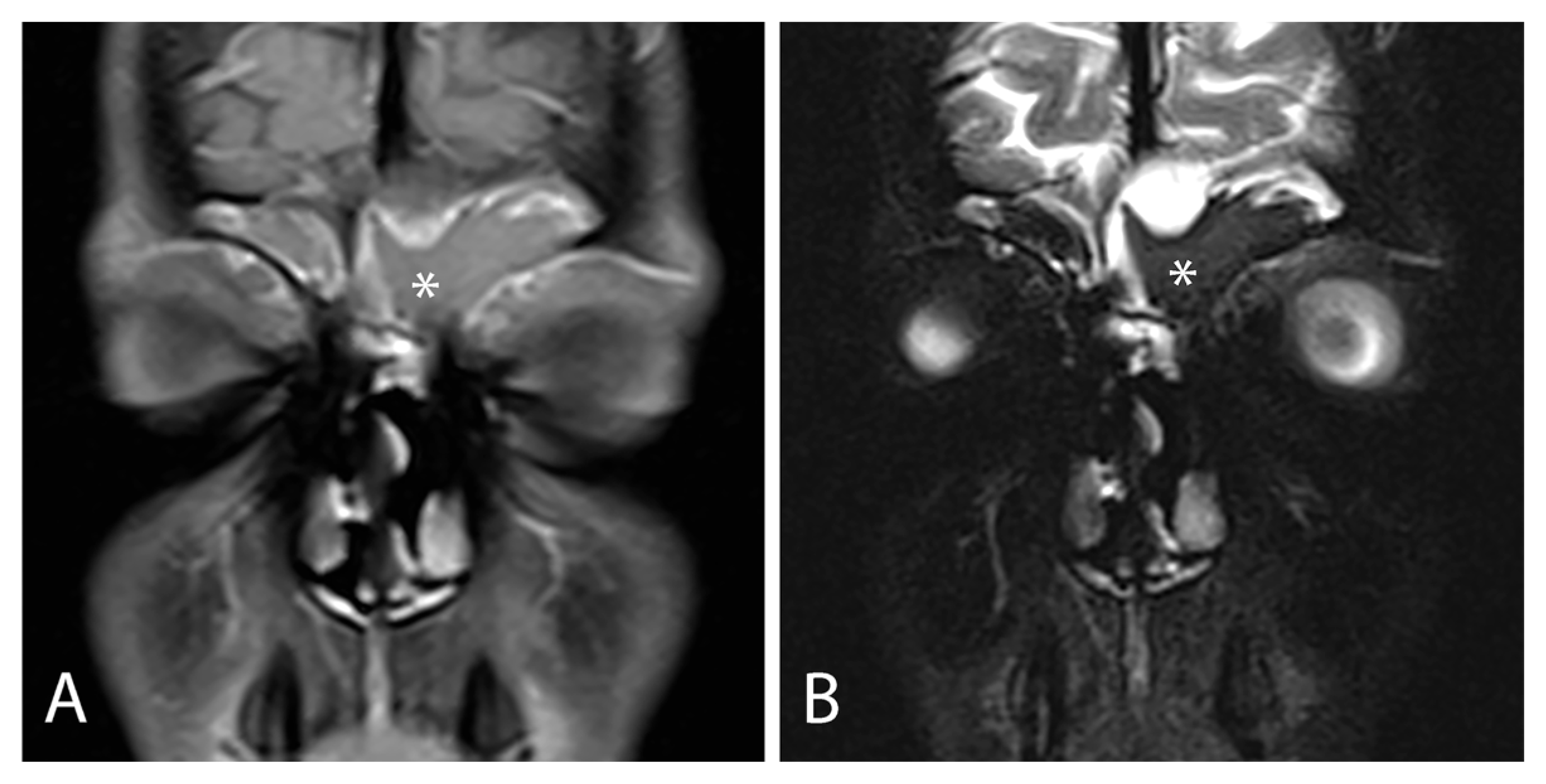

3.1.3. Radiological Findings

3.1.4. Microbiological Findings

3.2. Surgical Technique

3.2.1. Goals of the Surgical Treatment

3.2.2. Surgical Technique: Primary and Revision Surgery

3.2.3. Risks and Complications

3.3. Outcomes

3.3.1. Endoscopic/Radiological Results and Follow-Up

3.3.2. Association with Medical Treatment

3.3.3. Impact on Quality of Life (QoL)

3.3.4. Influence on Lung Function

3.3.5. Improvement in Nitric Oxide Level Post FESS

4. Limitations of the Current Evidence and of This Review

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEA | anterior ethmoidal artery |

| ASV | amplicon sequence variant |

| CFTR | cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid leak |

| CF | cystic fibrosis |

| CRS | chronic rhinosinusitis |

| CT | computed tomography |

| EMMA | endoscopic maxillary mega-antrostomy |

| ETI | elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor |

| FESS | functional endoscopic sinus surgery |

| ICA | internal carotid artery |

| OMC | osteo-meatal complex |

| PFT | pulmonary function testing |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MEMM | modified endoscopic medial maxillectomy |

| nNO | nasal nitric oxide |

| QoL | quality of life |

| SN-5 | sinonasal-5 |

| SER | spheno-ethmoidal recess |

References

- Doull, I.J.M. Recent advances in cystic fibrosis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2001, 85, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratjen, F.; Döring, G. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2003, 361, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgin, F.W.; Huang, L.; Roberson, D.W.; Sawicki, G.S. Inter-hospital variation in the frequency of sinus surgery in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2015, 50, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, B.A.J.; Lands, L.C.; Saint-Martin, C.; Mascarella, M.A.; Manoukian, J.J.; Daniel, S.J.; Nguyen, L.H. Effect of the F508del genotype on outcomes of endoscopic sinus surgery in children with cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014, 78, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, C.W.; Gurucharri, M.J.; Lazar, R.H.; Long, T.E. Functional endonasal sinus surgery (FESS) in the pediatric age group. Laryngoscope 1989, 99, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Safi, C.; Gudis, D.A. Surgical Management of Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Cystic Fibrosis. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, R.L.; Bent, J.P. Meta-Analysis of Outcomes of Pediatric Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery. Laryngoscope 1998, 108, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlastarakos, P.V.; Fetta, M.; Segas, J.V.; Maragoudakis, P.; Nikolopoulos, T.P. Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery Improves Sinus-Related Symptoms and Quality of Life in Children with Chronic Rhinosinusitis: A Systematic Analysis and Meta-Analysis of Published Interventional Studies. Clin. Pediatr. 2013, 52, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitjean, M.; Letierce, A.; Bonnel, A.; Reix, P.; Deneuville, E.; Stremler, N.; Luscan, R.; Couloigner, V.; Mely, L.; Bessaci, K.; et al. Beyond the Lung. Impact of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor on Sinonasal Disease in Children With Cystic Fibrosis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2025, 15, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, M.; Skov, M.; Andersen, I.S.B.; Von Buchwald, C.; Aanæs, K. The criteria for chronic rhinosinusitis in children with cystic fibrosis are rarely fulfilled after initiation of CFTR modulator treatment. APMIS 2024, 132, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, A.R. The changing paradigm for cystic fibrosis in rhinology. Rhinology 2025, 63, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.E.; Farzal, Z.; Daniels, M.L.A.; Thorp, B.D.; Zanation, A.M.; Senior, B.A.; Ebert, C.S., Jr.; Kimple, A.J. Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Modulator Therapy: A Review for the Otolaryngologist. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2020, 34, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, J.M.; Friedman, E.M.; Rubin, B.K. Nasal and sinus disease in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2008, 9, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.K.; McNamara, S.; Park, J.S.; Vajda, J.; Gibson, R.L.; Parikh, S.R. Sinonasal Quality of Life in Children With Cystic Fibrosis. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 142, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gysin, C.; Alothman, G.A.; Papsin, B.C. Sinonasal disease in cystic fibrosis: Clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and management. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2000, 30, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cicco, M.; Costantini, D.; Padoan, R.; Colombo, C. Paranasal mucoceles in children with cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2005, 69, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I.; et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020, 58, 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, M.W.; Gould, J.; Upton, G.J.G. Nasal Polyposis in Children with Cystic Fibrosis: A Long-Term Follow-up Study. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2002, 111, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, B.A.; Lands, L.C.; Mascarella, M.A.; Fanous, A.; Saint-Martin, C.; Manoukian, J.J.; Nguyen, L.H. Lund–Mackay and modified Lund–Mackay score for sinus surgery in children with cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 79, 1341–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergin, O.; Kawai, K.; MacDougall, R.D.; Robson, C.D.; Moritz, E.; Cunningham, M.; Adil, E. Sinus Computed Tomography Imaging in Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis: Added Value? Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2016, 155, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurphy, A.B.; Morriss, C.; Roberts, D.B.; Friedman, E.M. The Usefulness of Computed Tomography Scans in Cystic Fibrosis Patients with Chronic Sinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. 2007, 21, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommerburg, O.; Wielpütz, M.O.; Trame, J.P.; Wuennemann, F.; Opdazaite, E.; Stahl, M.; Puderbach, M.U.; Kopp-Schneider, A.; Fritzsching, E.; Kauczor, H.U.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Detects Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Infants and Preschool Children with Cystic Fibrosis. Ann. ATS 2020, 17, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavin, J.; Bhushan, B.; Schroeder, J.W. Correlation between respiratory cultures and sinus cultures in children with cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 77, 686–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, S.K.; Feddema, E.; Boyer, H.C.; Hunter, R.C. Diversity of cystic fibrosis chronic rhinosinusitis microbiota correlates with different pathogen dominance. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2021, 20, 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgin, F.W.; Rowe, S.M.; Wade, M.B.; Gaggar, A.; Leon, K.J.; Young, K.R.; Woodworth, B.A. Extensive Surgical and Comprehensive Postoperative Medical Management for Cystic Fibrosis Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2012, 26, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuyler, J.P. Follow-up of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery on Children with Cystic Fibrosis. Arch. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 1992, 118, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosbe, K.W.; Jones, D.T.; Rahbar, R.; Lahiri, T.; Auerbach, A.D. Endoscopic sinus surgery in cystic fibrosis: Do patients benefit from surgery? Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2001, 61, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovell, L.C.; Wang, J.; Ishman, S.L.; Zeitlin, P.L.; Boss, E.F. Cystic Fibrosis and Sinusitis in Children: Outcomes and Socioeconomic Status. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2011, 145, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, A.J.; Leung, R.; Ratjen, F.; James, A.L. Effect of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery on Pulmonary Function and Microbial Pathogens in a Pediatric Population With Cystic Fibrosis. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 137, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aanaes, K.; Johansen, H.K.; Skov, M.; Buchvald, F.F.; Hjuler, T.; Pressler, T.; Hoiby, N.; Nielsen, K.G.; von Buchwald, C. Clinical effects of sinus surgery and adjuvant therapy in cystic fibrosis patients—can chronic lung infections be postponed? Rhinology 2013, 51, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumin, D.; Hayes, D.; Kirkby, S.E.; Tobias, J.D.; McKee, C. Safety of endoscopic sinus surgery in children with cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 98, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triglia, J.M.; Dessi, P.; Cannoni, M.; Pech, A. Intranasal ethmoidectomy in nasal polyposis in children. Indications and results. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 1992, 23, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, D.Y.; Hwang, P.H. Results of Endoscopic Maxillary Mega-antrostomy in Recalcitrant Maxillary Sinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. 2008, 22, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anat, S. Management of recurrent sinus disease in children with cystic fibrosis: A combined approach. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2006, 135, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachert, C.; Marple, B.; Hosemann, W.; Cavaliere, C.; Wen, W.; Zhang, N. Endotypes of Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps: Pathology and Possible Therapeutic Implications. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 1514–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turri-Zanoni, M.; Arosio, A.D.; Stamm, A.C.; Battaglia, P.; Salzano, G.; Romano, A.; Castelnuovo, P.; Canevari, F.R. Septal branches of the anterior ethmoidal artery: Anatomical considerations and clinical implications in the management of refractory epistaxis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 275, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelnuovo, P.; Turri-Zanoni, M.; Battaglia, P.; Locatelli, D.; Dallan, I. Endoscopic Endonasal Management of Orbital Pathologies. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 26, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlucchi, M.; Staurenghi, G.; Rossi Brunori, P.; Tomenzoli, D.; Nicolai, P. Transnasal endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy for the treatment of lacrimal pathway stenoses in pediatric patients. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2003, 67, 1069–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baban, M.I.A.; Hadi, M.; Gallo, S.; Zocchi, J.; Turri-Zanoni, M.; Castelnuovo, P. Radiological and clinical interpretation of the patients with CSF leaks developed during or after endoscopic sinus surgery. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 274, 2827–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelli, E.; Bignami, M.; Digilio, E.; Fusetti, S.; Volo, T.; Castelnuovo, P. Post-traumatic optic neuropathy: Our surgical and medical protocol. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 272, 3301–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Higgins, T.; Ishman, S.L.; Boss, E.F.; Benke, J.R.; Lin, S.Y. Medical management of chronic rhinosinusitis in cystic fibrosis: A systematic review. Laryngoscope 2014, 124, 1308–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Videler, W.J.M.; Georgalas, C.; Menger, D.J.; Freling, N.J.M.; Van Drunen, C.M.; Fokkens, W.J. Osteitic bone in recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis. Rhinology 2011, 49, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cicco, M.; Peroni, D.; Sepich, M.; Tozzi, M.G.; Comberiati, P.; Cutrera, R. Hyaluronic acid for the treatment of airway diseases in children: Little evidence for few indications. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 2156–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchi, A.; Castelnuovo, P.; Terranova, P.; Digilio, E. Effects of Sodium Hyaluronate in Children with Recurrent Upper Respiratory Tract Infections: Results of a Randomised Controlled Study. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2013, 26, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuca, I.M.; Dediu, M.; Popin, D.; Pop, L.L.; Tamas, L.A.; Pilut, C.N.; Almajan Guta, B.; Popa, Z.L. Antibiotherapy in Children with Cystic Fibrosis-An Extensive Review. Children 2022, 9, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnson, B.J.; Choby, G.W.; O’Brien, E.K. Chronic rhinosinusitis in patients with cystic fibrosis—Current management and new treatments. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2020, 5, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, A.L.; Kimple, A.; Goralski, J.L.; Beswick, D.M.; Gupta, A.; Li, D.A.; Branstetter, B.F.; Nouraie, S.M.; Shaffer, A.D.; Senior, B.; et al. Elexacaftor–Tezacaftor–Ivacaftor Improves Sinonasal Outcomes in Young Children With Cystic Fibrosis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2025, 15, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, N.; Thamboo, A.; Habib, A.; Nayak, J.V.; Hwang, P.H. Determinants and outcomes of upfront surgery versus medical therapy for chronic rhinosinusitis in cystic fibrosis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017, 7, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, D.J.; Rosenfeld, R.M. Quality of Life for Children with Persistent Sinonasal Symptoms. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2003, 128, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, J.L.; Virella-Lowell, I.; Schlosser, R.J.; Soler, Z.M. Quantitative Sinonasal Symptom Assessment in an Unselected Pediatric Population with Cystic Fibrosis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2015, 29, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Peteghem, A.; Clement, P.A.R. Influence of extensive functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) on facial growth in children with cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2006, 70, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triglia, J.; Nicollas, R. Nasal and Sinus Polyposis in Children. Laryngoscope 1997, 107, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Winter–de Groot, K.M.; Van Haren Noman, S.; Speleman, L.; Schilder, A.G.M.; Van Der Ent, C.K. Nasal Nitric Oxide Levels and Nasal Polyposis in Children and Adolescents with Cystic Fibrosis. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 139, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symptoms | Endoscopic Findings | Radiological Findings | Microbiological Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinonasal Nasal obstruction (81.1%) (unilateral or bilateral) Rhinorrhea (50%) Hyposmia or anosmia (27%) Headache (50%) Facial pain Ocular Epiphora Exophtalmia Hyperemic conjunctive Others Mouth breathing Chronic cough Throat clearing Halitosis Activity intolerance Agitated or restless sleep Snoring Sleep apnea Failure to thrive | Nasal mucosa congestion, particularly with turbinates Prominent uncinate process Bulging of lateral wall (unilateral or bilateral) Nasal polyps (33–56.5%) Septal deformity Choanal stenosis Viscous and/or purulent nasal secretions Adenoid hypertrophy Cobblestoning of posterior pharynx | CT Opacification of the sinus (hourglass image) Mucocele Bulging or displacement of lateral nasal wall Demineralization of uncinate process Hypoplasia or aplasia of the paranasal sinuses Inverse relationship between the size of anterior and posterior ethmoid sinus Decreased pneumatization of the sinus MRI Mucosal swelling Mucopyoceles Polyps Maxillary sinus wall deformation Delay pneumatization | Bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa Staphylococcus aureus Haemophilus influenzae Streptococcus species Achromobacter xylosoxidans Fungi Candida albicans Aspergillus fumigatus Exserophilum species Penicillum species |

| Study (First Author, Year) | Type of Study, Setting | Sample (CF Children) | Age Range (Years) | Type/ Extent of FESS | Follow-Up | Main Outcome Measures | Main Findings | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuyler, 1992 [26] | Prospective, single center | 10 CF children; 7 underwent FESS | 3–19 | Endoscopic sinus surgery tailored to extent of disease | 2–3 years | CT appearance of sinuses; patient/parent-reported symptom change | Radiologic disease persisted or recurred in all children, but all patients/parents reported subjective symptomatic benefit | Very small sample; no control group; non-standardized symptom assessment |

| Rosbe, 2001 [27] | Retrospective, tertiary children’s hospital | 66 children with CF (including 8 lung transplant recipients); 112 ESS procedures | mean age 17 | FESS for CRS/polyposis; revision surgery in 25 patients | 6–12 months | Oral/inhaled steroid use, pulmonary function tests, inpatient hospital days | No significant change in PFTs or steroid requirements; possible reduction in hospitalization days in the 6 months after surgery | Retrospective, uncontrolled; index hospitalization confounded admission data; no standardized sinonasal QoL measures |

| Kovell, 2011 [28] | Retrospective, tertiary CF center | 62 children with CF and sinusitis; 21 underwent ESS, 41 managed medically | 0–21 | Extent of FESS not detailed (performed for CRS/polyposis) | Up to 3 years | FEV1% predicted, FVC% predicted; socioeconomic status | After adjustment for Medicaid status, children who underwent ESS had higher FEV1 and FVC over time compared with non-surgical patients | Non-randomized; selection bias (polyposis more common in ESS group); no direct sinonasal symptom scores |

| Osborn, 2011 [29] | Retrospective, single-center series | 41 children with CF undergoing ESS | 5–18 | FESS for CRS/nasal polyps | Variable (pre- and post-operative PFTs and cultures) | Pulmonary function tests; upper and lower airway microbial cultures | ESS did not significantly improve PFTs or alter respiratory tract microbial colonization patterns | Retrospective; no control group; follow-up duration heterogeneous; quality-of-life data not collected |

| Do, 2014 [4] | Retrospective, tertiary pediatric hospital | 153 children with CF; subset required FESS | mean age 7.1 | FESS of varying extent; extent and revision rates compared across genotypes | ≥1 year | Need for FESS, Lund–Mackay CT score, extent of surgery, length of stay, revision surgery | F508del genotype was not associated with increased need for FESS, greater surgical extent, or higher revision rates | Focused on genotype–phenotype; did not evaluate symptom scores or pulmonary outcomes; heterogeneous surgical techniques |

| Aanaes, 2013 [30] | Prospective, national CF center | 106 patients with CF (children and adults) | 6–50 (mixed pediatric/adult) | Extensive FESS with systematic sinus irrigation and intensive postoperative topical therapy | 12 months | Sinus and lower airway bacteriology, number of positive cultures, FEV1/FVC, BMI, CF-specific antibodies, sinonasal symptoms | Significant reduction in positive lower airway cultures and intermittent colonization after FESS; only minimal changes in FEV1/FVC; sinonasal symptoms improved | Mixed adult and pediatric population (results not stratified by age); no control group; intensive adjuvant therapy makes surgical effect difficult to isolate |

| Tumin, 2017 [31] | Retrospective, multicenter registry study (ACS NSQIP-P) | 213 children with CF vs. 821 without CF undergoing elective ESS | mean age 10 | ESS as coded in registry (extent not specified) | 30 days | Prolonged hospital stay (>1 day), 30-day readmission and unplanned reoperation | CF children had longer hospital stays than non-CF peers, but similar 30-day readmission and reoperation rates, supporting overall safety of ESS in CF | Registry data; no symptom, endoscopic, or radiologic outcomes; extent of surgery and CF disease severity not captured |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galluzzi, F.; Garavello, W.; Dalfino, G.; Bernardi, F.D.; Castelnuovo, P.; Turri-Zanoni, M. The Role of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Children with Cystic Fibrosis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8835. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248835

Galluzzi F, Garavello W, Dalfino G, Bernardi FD, Castelnuovo P, Turri-Zanoni M. The Role of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Children with Cystic Fibrosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8835. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248835

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalluzzi, Francesca, Werner Garavello, Gianluca Dalfino, Francesca De Bernardi, Paolo Castelnuovo, and Mario Turri-Zanoni. 2025. "The Role of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Children with Cystic Fibrosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8835. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248835

APA StyleGalluzzi, F., Garavello, W., Dalfino, G., Bernardi, F. D., Castelnuovo, P., & Turri-Zanoni, M. (2025). The Role of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Children with Cystic Fibrosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8835. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248835