In the Mouth or in the Gut? Innovation Through Implementing Oral and Gastrointestinal Health Science in Chronic Pain Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

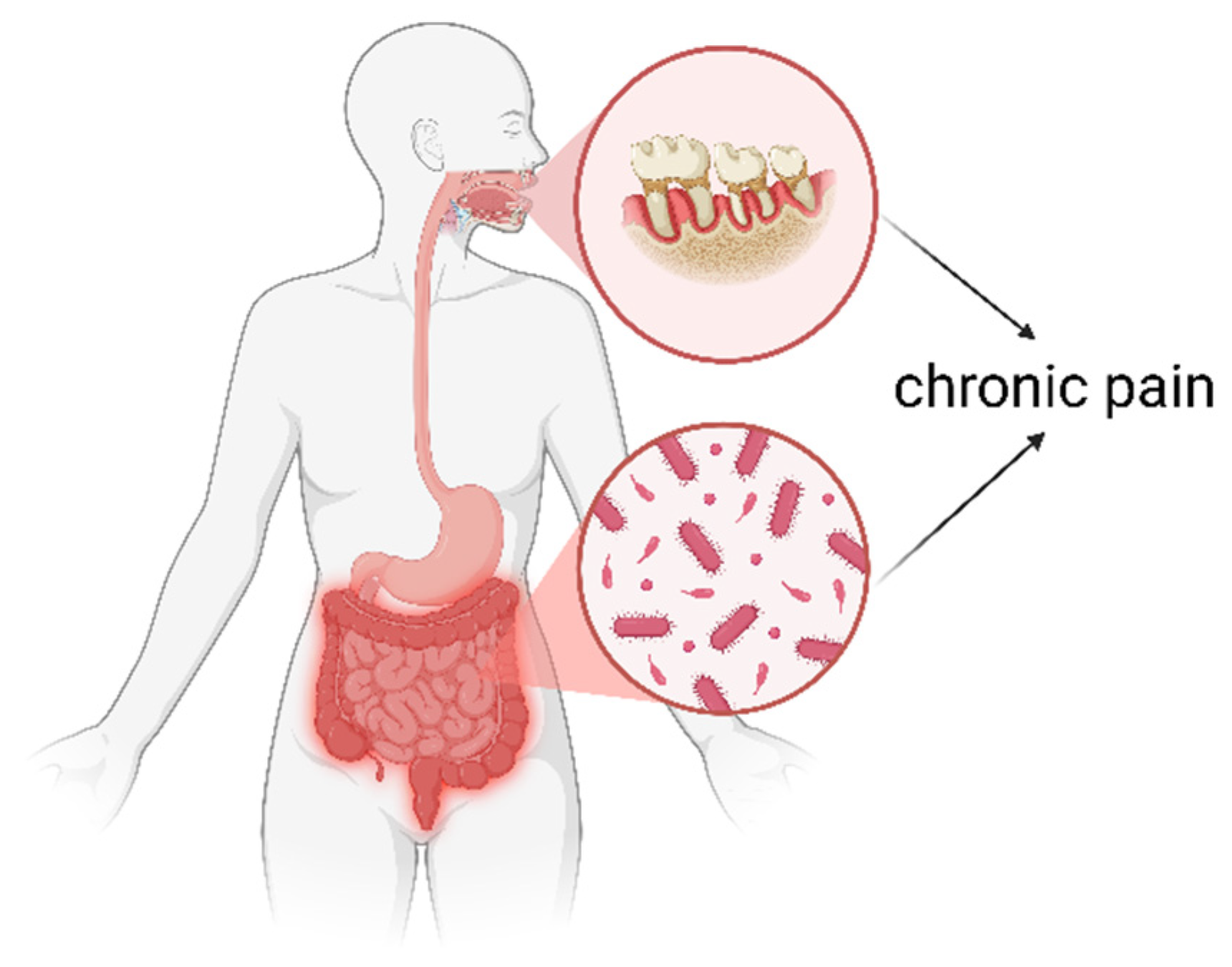

3. The Altered Gut Microbiome in People with Chronic Pain

4. The Role of Comorbidities in Gut Dysbiosis in Chronic Pain: Awakening the Gut Feeling

5. Poor Oral Health in People with Chronic Pain

6. Lifestyle Medicine 2.0 for Chronic Pain: Implementing Gastrointestinal and Oral Health Science

6.1. Evaluation of Oral and Gut Health in All Patients with Chronic Pain

6.2. Oral Medication Intake (History), Including Polypharmacy

6.3. Oral and Gut Health Science Education

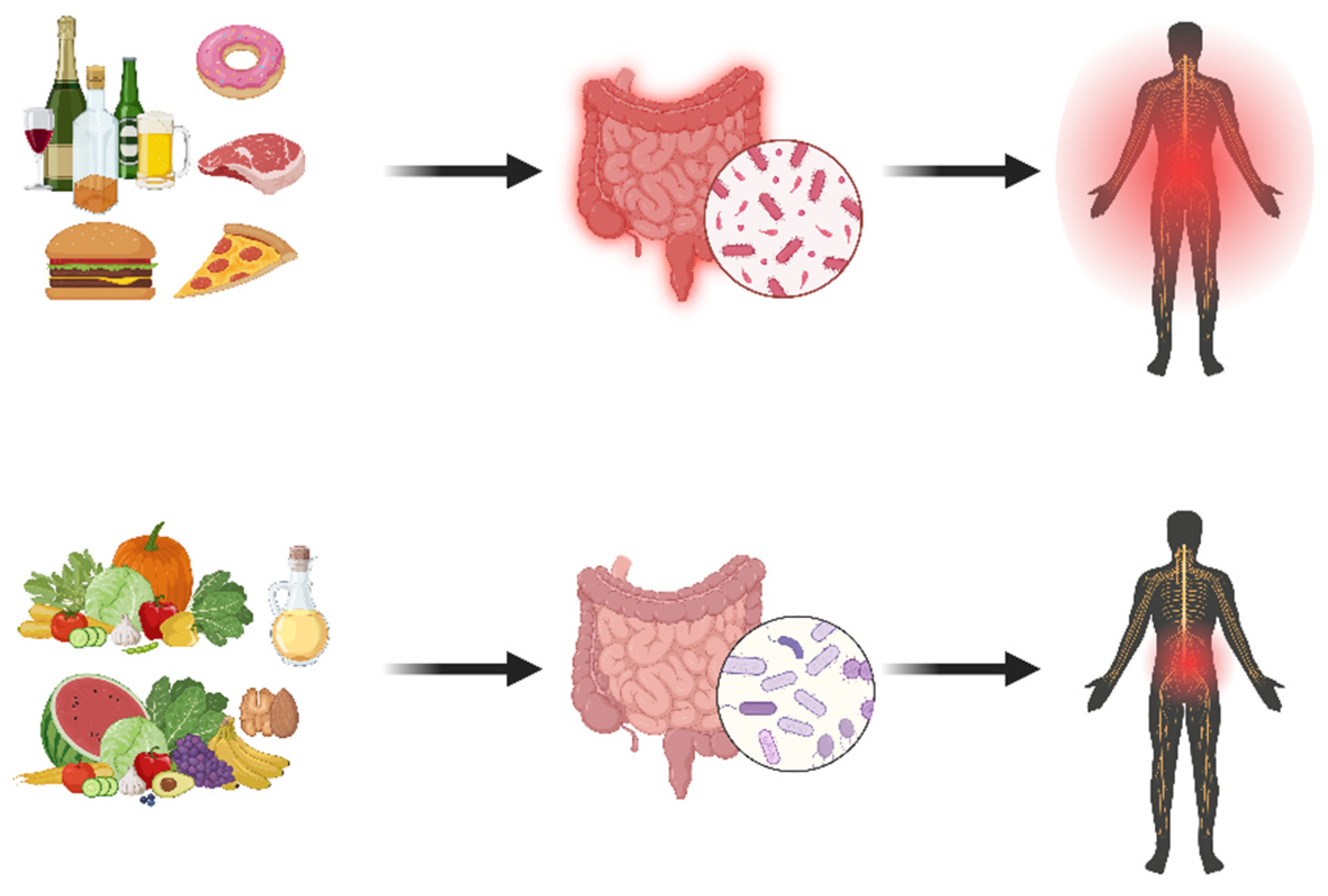

6.4. Expanding the Importance of Dietary Interventions

6.5. Additional Treatment Options

7. Limitation

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen, S.P.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W.M. Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet 2021, 397, 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Rodríguez, L.; Borràs, X.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Pérez-Aranda, A.; Angarita-Osorio, N.; Moreno-Peral, P.; Montero-Marin, J.; García-Campayo, J.; Carvalho, A.F.; Maes, M.; et al. Peripheral immune aberrations in fibromyalgia: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canlı, K.; Billens, A.; Van Oosterwijck, J.; Meeus, M.; De Meulemeester, K. Systemic Cytokine Level Differences in Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Spinal Pain Compared to Healthy Controls and Its Association with Pain Severity: A Systematic Review. Pain Med. 2022, 23, 1947–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; George, S.Z.; Clauw, D.J.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Kosek, E.; Ickmans, K.; Fernández-Carnero, J.; Polli, A.; Kapreli, E.; Huysmans, E.; et al. Central sensitisation in chronic pain conditions: Latest discoveries and their potential for precision medicine. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021, 3, e383–e392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treede, R.D.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Finnerup, N.B.; First, M.B.; et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain 2015, 156, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ICD-11—MG30 Chronic Pain. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse/2025-01/mms/en#1581976053 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Nijs, J.; D’Hondt, E.; Clarys, P.; Deliens, T.; Polli, A.; Malfliet, A.; Coppieters, I.; Willaert, W.; Tumkaya Yilmaz, S.; Elma, Ö.; et al. Lifestyle and Chronic Pain across the Lifespan: An Inconvenient Truth? PM&R 2020, 12, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, J.; Brown, M.; Alexander, S. Update in the Treatment of Chronic Pain within Pediatric Patients. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2017, 47, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A.L.; Lee, J.; Ehrlich-Jones, L.; Semanik, P.A.; Song, J.; Pellegrini, C.A.; Pinto Pt, D.; Dunlop, D.D.; Chang, R.W. A randomized trial of a motivational interviewing intervention to increase lifestyle physical activity and improve self-reported function in adults with arthritis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2018, 47, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahousse, A.; Roose, E.; Leysen, L.; Yilmaz, S.T.; Mostaqim, K.; Reis, F.; Rheel, E.; Beckwée, D.; Nijs, J. Lifestyle and Pain following Cancer: State-of-the-Art and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrance, N.; Elliott, A.M.; Lee, A.J.; Smith, B.H. Severe chronic pain is associated with increased 10 year mortality. A cohort record linkage study. Eur. J. Pain 2010, 14, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBeth, J.; Symmons, D.P.; Silman, A.J.; Allison, T.; Webb, R.; Brammah, T.; Macfarlane, G.J. Musculoskeletal pain is associated with a long-term increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular-related mortality. Rheumatology 2009, 48, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodson, N.J.; Smith, B.H.; Hocking, L.J.; McGilchrist, M.M.; Dominiczak, A.F.; Morris, A.; Porteous, D.J.; Goebel, A. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome are more prevalent in people reporting chronic pain: Results from a cross-sectional general population study. Pain 2013, 154, 1595–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Ritz, B.; Arah, O.A. Causal Effect of Chronic Pain on Mortality Through Opioid Prescriptions: Application of the Front-Door Formula. Epidemiology 2022, 33, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.B.S.; Meng, J.; Zhang, J. Does Low Grade Systemic Inflammation Have a Role in Chronic Pain? Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 785214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; Malfliet, A.; Roose, E.; Lahousse, A.; Van Bogaert, W.; Johansson, E.; Runge, N.; Goossens, Z.; Labie, C.; Bilterys, T. Personalized multimodal lifestyle intervention as the best-evidenced treatment for chronic pain: State-of-the-art clinical perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenbergh, S.; De Coninck, L.; Cordyn, S.; Excelmans, E.; Stukken, L.; Goossens, M.; Nijs, J.; Morlion, B.; Janssen, N.; Vermeulen, L.; et al. Multimodal Management of Chronic Primary Pain; Worel: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tieppo, A.M.; Tieppo, J.S.; Rivetti, L.A. Analysis of Intestinal Bacterial Microbiota in Individuals with and without Chronic Low Back Pain. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 7339–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, C.G.; Radjabzadeh, D.; Medina-Gomez, C.; Garmaeva, S.; Schiphof, D.; Arp, P.; Koet, T.; Kurilshikov, A.; Fu, J.; Ikram, M.A.; et al. Intestinal microbiome composition and its relation to joint pain and inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahony, S.M.O.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. The gut microbiota as a key regulator of visceral pain. Pain 2017, 158 (Suppl. S1), S19–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhu, N.T.; Chen, D.Y.; Yang, Y.S.H.; Lo, Y.C.; Kang, J.H. Associations Between Brain-Gut Axis and Psychological Distress in Fibromyalgia: A Microbiota and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. J. Pain 2024, 25, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugo, C.W.; Church, E.; Horniblow, R.D.; Mollan, S.P.; Botfield, H.; Hill, L.J.; Sinclair, A.J.; Grech, O. Unravelling the gut-brain connection: A systematic review of migraine and the gut microbiome. J. Headache Pain 2025, 26, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdrich, S.; Gelissen, I.C.; Vuyisich, M.; Toma, R.; Harnett, J.E. An association between poor oral health, oral microbiota, and pain identified in New Zealand women with central sensitisation disorders: A prospective clinical study. Front. Pain Res. 2025, 6, 1577193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xue, D.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, P.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.B. Association between periodontitis and disc structural failure in older adults with lumbar degenerative disorders: A prospective cohort study. BMC Surg. 2023, 23, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.S.; Lai, J.N.; Veeravalli, J.J.; Chiu, L.T.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Wei, J.C. Fibromyalgia and periodontitis: Bidirectional associations in population-based 15-year retrospective cohorts. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Pablo, P.; Dietrich, T.; McAlindon, T.E. Association of periodontal disease and tooth loss with rheumatoid arthritis in the US population. J. Rheumatol. 2008, 35, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, T.S.; Senapati, S.G.; Gadam, S.; Mannam, H.; Voruganti, H.V.; Abbasi, Z.; Abhinav, T.; Challa, A.B.; Pallipamu, N.; Bheemisetty, N.; et al. The Impact of Microbiota on the Gut-Brain Axis: Examining the Complex Interplay and Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lu, T.; Chen, W.; Yan, W.; Yuan, K.; Shi, L.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; Shi, J.; et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in sleep disorders. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 65, 101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, X.; Li, L. Human gut microbiome: The second genome of human body. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.-M. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falony, G.; Joossens, M.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Wang, J.; Darzi, Y.; Faust, K.; Kurilshikov, A.; Bonder, M.J.; Valles-Colomer, M.; Vandeputte, D. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science 2016, 352, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.O.; Bariguian, F.; Mobasheri, A. The Potential Role of Probiotics in the Management of Osteoarthritis Pain: Current Status and Future Prospects. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2023, 25, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Zmora, N.; Adolph, T.E.; Elinav, E. The intestinal microbiota fuelling metabolic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manske, S. The Microbiome’s Role in Chronic Pain and Inflammation. Integr. Med. 2024, 23, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Wen, S.; Hu, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, G.; Zeng, Q.; Zou, J. Multiple reports on the causal relationship between various chronic pain and gut microbiota: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1369996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudman, L.; Demuyser, T.; Pilitsis, J.G.; Billot, M.; Roulaud, M.; Rigoard, P.; Moens, M. Gut dysbiosis in patients with chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1342833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.N.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.Z.; Chen, Y.J.; Shen, X.Z.; Liu, T.T. Altered molecular signature of intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared with healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2017, 49, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ouyang, D.; Liu, L.; Ren, D.; Wu, X. Association between endometriosis and gut microbiota: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1552134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Xiong, L.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Chen, M. Alterations of gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawarathna, G.; Fakhruddin, K.S.; Shorbagi, A.; Samaranayake, L.P. The gut microbiota-neuroimmune crosstalk and neuropathic pain: A scoping review. Gut Microbiome 2023, 4, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.S.; Tissier, A.; Bail, J.R.; Novak, J.R.; Morrow, C.D.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Frugé, A.D. Health-related quality of life is associated with fecal microbial composition in breast cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 31, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.W.; Zhao, B.C.; Yang, X.; Lei, S.H.; Jiang, Y.M.; Liu, K.X. Relationships of sleep disturbance, intestinal microbiota, and postoperative pain in breast cancer patients: A prospective observational study. Sleep Breath. 2021, 25, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiang, J.H.; Peng, X.Y.; Liu, M.; Sun, L.J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.Y.; Chen, Z.B.; Tang, Z.Q.; Cheng, L. Characteristic alterations of gut microbiota and serum metabolites in patients with chronic tinnitus: A multi-omics analysis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0187824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Hu, S.; Li, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, N. Causal associations between gut microbiota with intervertebral disk degeneration, low back pain, and sciatica: A Mendelian randomization study. Eur. Spine J. 2024, 33, 1424–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Hold, G.L.; Flint, H.J. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Lemberg, D.A.; Day, A.S.; Leach, S.T. The Interplay Between Immunological Status and Gut Microbial Dysbiosis in the Development of the Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2025, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdrich, S.; Hawrelak, J.A.; Myers, S.P.; Harnett, J.E. A systematic review of the association between fibromyalgia and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 1756284820977402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C.; Cristiani, C.M.; Ilari, S.; Passacatini, L.C.; Malafoglia, V.; Viglietto, G.; Maiuolo, J.; Oppedisano, F.; Palma, E.; Tomino, C. Fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome interaction: A possible role for gut microbiota and gut-brain axis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, P.Y.; Shi, L.H. Gut Microbiota in Adults with Chronic Widespread Pain: A Systematic Review. Diseases 2025, 13, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.A.; Broderick, J.E. Obesity and pain are associated in the United States. Obesity 2012, 20, 1491–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okifuji, A.; Hare, B.D. The association between chronic pain and obesity. J. Pain Res. 2015, 8, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaodhiar, L.; Ling, P.R.; Blackburn, G.L.; Bistrian, B.R. Serum levels of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein correlate with body mass index across the broad range of obesity. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2004, 28, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäffler, A.; Schölmerich, J.; Salzberger, B. Adipose tissue as an immunological organ: Toll-like receptors, C1q/TNFs and CTRPs. Trends Immunol. 2007, 28, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.J.; Santos, A.; Prada, P.O. Linking Gut Microbiota and Inflammation to Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Physiology 2016, 31, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Chen, L.H.; Xing, C.; Liu, T. Pain regulation by gut microbiota: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker Nitert, M.; Mousa, A.; Barrett, H.L.; Naderpoor, N.; de Courten, B. Altered Gut Microbiota Composition Is Associated With Back Pain in Overweight and Obese Individuals. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Gao, G.; Kwok, L.Y.; Lv, H.; Sun, Z. Insomnia: The gut microbiome connection, prospects for probiotic and postbiotic therapies, and future directions. J. Adv. Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, L.M.; Iverson, G.L. Disrupted sleep patterns and daily functioning in patients with chronic pain. Pain Res. Manag. 2002, 7, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigeon, W.R.; Moynihan, J.; Matteson-Rusby, S.; Jungquist, C.R.; Xia, Y.; Tu, X.; Perlis, M.L. Comparative effectiveness of CBT interventions for co-morbid chronic pain & insomnia: A pilot study. Behav. Res. Ther. 2012, 50, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullington, J.M.; Simpson, N.S.; Meier-Ewert, H.K.; Haack, M. Sleep loss and inflammation. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 24, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.R.; Olmstead, R.; Carroll, J.E. Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Duration, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies and Experimental Sleep Deprivation. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garcia, F.; Juarez-Aguilar, E.; Santiago-Garcia, J.; Cardinali, D.P. Ghrelin and its interactions with growth hormone, leptin and orexins: Implications for the sleep-wake cycle and metabolism. Sleep. Med. Rev. 2014, 18, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.L.E.; Thoren, E.; Sylwander, C.; Bergman, S. Associations between chronic widespread pain, pressure pain thresholds, leptin, and metabolic factors in individuals with knee pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, S.; Lin, L.; Austin, D.; Young, T.; Mignot, E. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004, 1, e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejbuk, M.; Siebieszuk, A.; Witkowska, A.M. The role of gut microbiome in sleep quality and health: Dietary strategies for microbiota support. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, S.; Chen, S.; Li, C.; Chan, Y.L.; Chan, N.Y.; Wing, Y.K.; Chan, F.K.L.; Su, Q.; Ng, S.C. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Insomnia: A Systematic Review of Case-Control Studies. Life 2025, 15, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.; Martucci, M.; Sciara, G.; Conte, M.; Medina, L.S.J.; Iattoni, L.; Miele, F.; Fonti, C.; Franceschi, C.; Brigidi, P.; et al. Towards a personalized prediction, prevention and therapy of insomnia: Gut microbiota profile can discriminate between paradoxical and objective insomnia in post-menopausal women. EPMA J. 2024, 15, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, M.T.; Fang, J.T.; Liu, G.H.; Yeh, Y.M.; Chen, N.H.; Lin, C.M.; Wu, K.Y.; Huang, C.M.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, T.M.C. Better objective sleep quality is associated with higher gut microbiota richness in older adults. Geroscience 2025, 47, 4121–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, R.V.; Ravyts, S.G.; Carnahan, N.D.; Bhattiprolu, K.; Harte, N.; McCaulley, C.C.; Vitalicia, L.; Rogers, A.B.; Wegener, S.T.; Dudeney, J. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among adults with chronic pain: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e250268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, C.A.; Diaz-Arteche, C.; Eliby, D.; Schwartz, O.S.; Simmons, J.G.; Cowan, C.S. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression—A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 83, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.A.; Rinaman, L.; Cryan, J.F. Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiol. Stress 2017, 7, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keightley, P.; Pavli, P.; Platten, J.; Looi, J.C. Gut feelings 2. Mind, mood and gut in inflammatory bowel disease: Approaches to psychiatric care. Australas. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smythies, L.E.; Smythies, J.R. Microbiota, the immune system, black moods and the brain—Melancholia updated. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, R.A.; Foster, J.A. Gut brain axis: Diet microbiota interactions and implications for modulation of anxiety and depression. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.S.; Chan, S.Y.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Wang, S.I.; Wei, J.C.; Ashina, S. Tooth Loss and Chronic Pain: A Population-based Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Pain 2024, 25, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, N.H.; Wang, D.; Abey, S.K.; Sherwin, L.B.; Joseph, P.V.; Rahim-Williams, B.; Ferguson, E.G.; Henderson, W.A. The microbiome of the oral mucosa in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yin, T.; He, M.; Fang, C.; Tang, X.; Peng, S.; Liu, Y. Association of periodontitis, tooth loss, and self-rated oral health with circadian syndrome in US adults: A cross-sectional population study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Sun, Q.; Han, F.; Dong, M. Bidirectional Relationship Between Dental Diseases and Sleep Disturbances in Pediatric Patients. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2025, 11, e70191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, F.; Hu, X. Oral health and sleep disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed. Rep. 2025, 22, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, B.; Lapsley, C.; McDowell, A.; Miliotis, G.; McLafferty, M.; O’Neill, S.M.; Coleman, S.; McGinnity, T.M.; Bjourson, A.J.; Murray, E.K. Variations in the oral microbiome are associated with depression in young adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cademartori, M.G.; Gastal, M.T.; Nascimento, G.G.; Demarco, F.F.; Correa, M.B. Is depression associated with oral health outcomes in adults and elders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 2685–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, L.; Schulz, C.; Koletzko, L.; Malfertheiner, P. Systematic review: The effects of proton pump inhibitors on the microbiome of the digestive tract-evidence from next-generation sequencing studies. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishiro, T.; Oka, K.; Kuroki, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Tatsumi, K.; Saitoh, T.; Tobita, H.; Ishimura, N.; Sato, S.; Ishihara, S.; et al. Oral microbiome alterations of healthy volunteers with proton pump inhibitor. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 33, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Yin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Li, L.; Bi, X. Salivary microbiota composition before and after use of proton pump inhibitors in patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux: A self-control study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balmant, B.D.; Fonseca, D.C.; Rocha, I.M.; Callado, L.; Torrinhas, R.S.M.d.M.; Waitzberg, D.L. Dys-R Questionnaire: A Novel Screening Tool for Dysbiosis Linked to Impaired Gut Microbiota Richness. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revicki, D.A.; Wood, M.; Wiklund, I.; Crawley, J. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual. Life Res. 1997, 7, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Sun, C.; Li, M.; Hu, G.; Zhao, X.M.; Chen, W.H. Compared to histamine-2 receptor antagonist, proton pump inhibitor induces stronger oral-to-gut microbial transmission and gut microbiome alterations: A randomised controlled trial. Gut 2024, 73, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, H.; Xing, X.; Yang, J. Proton pump inhibitors alter gut microbiota by promoting oral microbiota translocation: A prospective interventional study. Gut 2024, 73, 1098–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gommers, L.M.M.; Hoenderop, J.G.J.; de Baaij, J.H.F. Mechanisms of proton pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia. Acta Physiol. 2022, 235, e13846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M.A.M.; Aronoff, D.M. The influence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the gut microbiome. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 178.e171–178.e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahlan, G.; De Clifford-Faugère, G.; Nguena Nguefack, H.L.; Guénette, L.; Pagé, M.G.; Blais, L.; Lacasse, A. Polypharmacy and Excessive Polypharmacy Among Persons Living with Chronic Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study on the Prevalence and Associated Factors. J. Pain Res. 2023, 16, 3085–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Algharably, E.A.E.; Budnick, A.; Wenzel, A.; Draeger, D.; Kreutz, R. High prevalence of multimorbidity and polypharmacy in elderly patients with chronic pain receiving home care are associated with multiple medication-related problems. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 686990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clifford-Faugère, G.; Nguena Nguefack, H.L.; Ménard, N.; Beaudoin, S.; Pagé, M.G.; Guénette, L.; Hudon, C.; Samb, O.M.; Lacasse, A. Unpacking excessive polypharmacy patterns among individuals living with chronic pain in Quebec: A longitudinal study. Front. Pain Res. 2025, 6, 1512878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raji, M.A.; Shah, R.; Westra, J.R.; Kuo, Y.F. Central nervous system active medication use in Medicare enrollees receiving home health care: Association with chronic pain and anxiety level. Pain 2025, 166, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, P. The gut remembers: The long-lasting effect of medication use on the gut microbiome. mSystems 2025, 10, e01076-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, N.; Nishijima, S.; Miyoshi-Akiyama, T.; Kojima, Y.; Kimura, M.; Aoki, R.; Ohsugi, M.; Ueki, K.; Miki, K.; Iwata, E. Population-level metagenomics uncovers distinct effects of multiple medications on the human gut microbiome. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 1038–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vich Vila, A.; Collij, V.; Sanna, S.; Sinha, T.; Imhann, F.; Bourgonje, A.R.; Mujagic, Z.; Jonkers, D.M.; Masclee, A.A.; Fu, J. Impact of commonly used drugs on the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aasmets, O.; Taba, N.; Krigul, K.L.; Andreson, R.; Estonian Biobank Research Team; Org, E. A hidden confounder for microbiome studies: Medications used years before sample collection. Msystems 2025, 10, e00541-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weersma, R.K.; Zhernakova, A.; Fu, J. Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut 2020, 69, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikeocha, I.J.; Al-Kabsi, A.M.; Miftahussurur, M.; Alshawsh, M.A. Pharmacomicrobiomics: Influence of gut microbiota on drug and xenobiotic metabolism. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.; Maiti, T.K.; Mahajan, D.; Das, B. Human gut microbiota and drug metabolism. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, L.; Berg, L.; Maier, L. Confounder or confederate? The interactions between drugs and the gut microbiome in psychiatric and neurological diseases. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 95, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klünemann, M.; Andrejev, S.; Blasche, S.; Mateus, A.; Phapale, P.; Devendran, S.; Vappiani, J.; Simon, B.; Scott, T.A.; Kafkia, E.; et al. Bioaccumulation of therapeutic drugs by human gut bacteria. Nature 2021, 597, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minari, T.P.; Pisani, L.P. Melatonin supplementation: New insights into health and disease. Sleep Breath. 2025, 29, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, F.; Souchak, J.; Nazaire, V.; Akkaoui, J.; Shil, R.; Carbajal, C.; Panda, K.; Delgado, D.C.; Claassen, I.; Moreno, S.; et al. A Connection Between the Gut Microbiome and Epigenetic Modification in Age-Related Cancer: A Narrative Review. Aging Dis. 2025, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, A.E.; Zimmermann-Kogadeeva, M.; Patil, K.R. Multimodal interactions of drugs, natural compounds and pollutants with the gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zádori, Z.S.; Király, K.; Al-Khrasani, M.; Gyires, K. Interactions between NSAIDs, opioids and the gut microbiota-future perspectives in the management of inflammation and pain. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 241, 108327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipalma, G.; Marinelli, G.; Ferrante, L.; Di Noia, A.; Carone, C.; Colonna, V.; Marotti, P.; Inchingolo, F.; Palermo, A.; Tartaglia, G.M. Modulating the Gut Microbiota to Target Neuroinflammation, Cognition and Mood: A Systematic Review of Human Studies with Relevance to Fibromyalgia. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.; Liang, D.; Qiu, J.; Fu, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Zheng, J.; Lin, L. Assessing the impact of common pain medications on gut microbiota composition and metabolites: Insights from a Mendelian randomization study. J. Med. Microbiol. 2025, 74, 002028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyseos, M.; Michael, J.; Ferreira, N.; Sophocleous, A. The effect of probiotics on the management of pain and inflammation in osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Xue, Q.; Luo, Y.; Yu, B.; Hua, B.; Liu, Z. The interplay between the microbiota and opioid in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1390046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roose, E.; Nijs, J.; Moseley, G.L. Striving for better outcomes of treating chronic pain: Integrating behavioural change strategies before, during, and after modern pain science education. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2023, 27, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elma, Ö.; Nijs, J.; Malfliet, A. The importance of nutritional factors on the road toward multimodal lifestyle interventions for persistent pain. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2024, 28, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, Y.; Soomro, N.; Wilson, G.; Dam, Y.; Meiklejohn, J.; Simpson, K.; Smith, R.; Brand-Miller, J.; Simic, M.; O’Connor, H.; et al. Train High Eat Low for Osteoarthritis study (THE LO study): Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. J. Physiother. 2015, 61, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.F.; Borzan, J.; Kalso, E.; Simonnet, G. Food, pain, and drugs: Does it matter what pain patients eat? Pain 2012, 153, 1993–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbanti, P.; Fofi, L.; Aurilia, C.; Egeo, G.; Caprio, M. Ketogenic diet in migraine: Rationale, findings and perspectives. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 38, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elma, O.; Yilmaz, S.T.; Deliens, T.; Coppieters, I.; Clarys, P.; Nijs, J.; Malfliet, A. Do Nutritional Factors Interact with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain? A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaegter, H.B.; Stoten, M.; Silseth, S.L.; Erlangsen, A.; Handberg, G.; Sondergaard, S.; Stenager, E. Cause-specific mortality of patients with severe chronic pain referred to a multidisciplinary pain clinic: A cohort register-linkage study. Scand. J. Pain 2019, 19, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, G.J.; Barnish, M.S.; Jones, G.T. Persons with chronic widespread pain experience excess mortality: Longitudinal results from UK Biobank and meta-analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, K.; Burrows, T.L.; Bruggink, L.; Malfliet, A.; Hayes, C.; Hodson, F.J.; Collins, C.E. Diet and Chronic Non-Cancer Pain: The State of the Art and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, K.; Burrows, T.L.; Rollo, M.E.; Chai, L.K.; Clarke, E.D.; Hayes, C.; Hodson, F.J.; Collins, C.E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nutrition interventions for chronic noncancer pain. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 32, 198–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeputte, D.; Joossens, M. Effects of low and high FODMAP diets on human gastrointestinal microbiota composition in adults with intestinal diseases: A systematic review. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, K.F.; Kindler, L.L.; Jones, K.D. Potential dietary links to central sensitization in fibromyalgia: Past reports and future directions. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2009, 35, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; Elma, O.; Yilmaz, S.T.; Mullie, P.; Vanderweeen, L.; Clarys, P.; Deliens, T.; Coppieters, I.; Weltens, N.; Van Oudenhove, L.; et al. Nutritional neurobiology and central nervous system sensitisation: Missing link in a comprehensive treatment for chronic pain? Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, R.; Karppinen, J.; Leino-Arjas, P.; Solovieva, S.; Viikari-Juntura, E. The association between obesity and low back pain: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 171, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data. Overweight and Obesity. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/overweight_text/en/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Vismara, L.; Menegoni, F.; Zaina, F.; Galli, M.; Negrini, S.; Capodaglio, P. Effect of obesity and low back pain on spinal mobility: A cross sectional study in women. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2010, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershkovich, O.; Friedlander, A.; Gordon, B.; Arzi, H.; Derazne, E.; Tzur, D.; Shamis, A.; Afek, A. Associations of body mass index and body height with low back pain in 829,791 adolescents. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 178, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulis, W.D.; Silva, S.; Koes, B.W.; van Middelkoop, M. Overweight and obesity are associated with musculoskeletal complaints as early as childhood: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhao, J.J.; Liu, D.W.; Tian, Q.B. Obesity as a Risk Factor for Low Back Pain: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Spine Surg. 2016, 31, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.M.; Urquhart, D.M.; Wang, Y.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J.; Wluka, A.E.; Cicuttini, F.M. Fat mass and fat distribution are associated with low back pain intensity and disability: Results from a cohort study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dario, A.B.; Ferreira, M.L.; Refshauge, K.; Sanchez-Romera, J.F.; Luque-Suarez, A.; Hopper, J.L.; Ordonana, J.R.; Ferreira, P.H. Are obesity and body fat distribution associated with low back pain in women? A population-based study of 1128 Spanish twins. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wei, H. Evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in middle-older aged: A systematic review and meta analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Chen, C. Body mass index and risk of knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landmark, T.; Romundstad, P.; Dale, O.; Borchgrevink, P.C.; Vatten, L.; Kaasa, S. Chronic pain: One year prevalence and associated characteristics (the HUNT pain study). Scand. J. Pain 2017, 4, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebschull, M.; Chapple, I. Evidence-based, personalised and minimally invasive treatment for periodontitis patients—The new EFP S3-level clinical treatment guidelines. Br. Dent. J. 2020, 229, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, D.; Sanz, M.; Kebschull, M.; Jepsen, S.; Sculean, A.; Berglundh, T.; Papapanou, P.N.; Chapple, I.; Tonetti, M.S. Treatment of stage IV periodontitis: The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49 (Suppl. S24), 4–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almabruk, B.A.; Bajafar, A.A.; Mohamed, A.N.; Al-Zahrani, S.A.; Albishi, N.M.; Aljarwan, R.; Aljaser, R.A.; Alghamdi, L.I.; Almutairi, T.S.; Alsolami, A.S. Efficacy of probiotics in the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Cureus 2024, 16, e75954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.X.; Shi, L.B.; Zhou, M.S.; Wu, J.; Shi, H.Y. Efficacy of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 72, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodoory, V.C.; Khasawneh, M.; Black, C.J.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Moayyedi, P.; Ford, A.C. Efficacy of Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 1206–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.; Harvey, A.G.; Lockley, S.W.; Dijk, D.J. Circadian rhythms and disorders of the timing of sleep. Lancet 2022, 400, 1061–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, C. Circadian disruption: What do we actually mean? Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 51, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tofani, G.S.S.; Leigh, S.J.; Gheorghe, C.E.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Wilmes, L.; Sen, P.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F. Gut microbiota regulates stress responsivity via the circadian system. Cell Metab. 2024, 37, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijs, J.; Mairesse, O.; Tang, N.K.Y. The importance of sleep in the paradigm shift from a tissue- and disease-based pain management approach towards multimodal lifestyle interventions for chronic pain. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2024, 28, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elma, Ö.; Tümkaya Yılmaz, S.; Nijs, J.; Clarys, P.; Coppieters, I.; Mertens, E.; Deliens, T.; Malfliet, A. Proinflammatory Dietary Intake Relates to Pain Sensitivity in Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Case-Control Study. J. Pain 2024, 25, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lu, S.; Chopra, N.; Cui, P.; Zhang, S.; Narulla, R.; Diwan, A.D. The association between low virulence organisms in different locations and intervertebral disc structural failure: A meta-analysis and systematic review. JOR Spine 2023, 6, e1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nijs, J.; Ahmed, I.; Vandeputte, D.; R. Goodin, B.; Adetayo, T.; Kindt, S.; Vanroose, M.; Elma, Ö.; Johansson, E.; Logghe, T.; et al. In the Mouth or in the Gut? Innovation Through Implementing Oral and Gastrointestinal Health Science in Chronic Pain Management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8812. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248812

Nijs J, Ahmed I, Vandeputte D, R. Goodin B, Adetayo T, Kindt S, Vanroose M, Elma Ö, Johansson E, Logghe T, et al. In the Mouth or in the Gut? Innovation Through Implementing Oral and Gastrointestinal Health Science in Chronic Pain Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8812. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248812

Chicago/Turabian StyleNijs, Jo, Ishtiaq Ahmed, Doris Vandeputte, Burel R. Goodin, Tolulope Adetayo, Sébastien Kindt, Matteo Vanroose, Ömer Elma, Elin Johansson, Tine Logghe, and et al. 2025. "In the Mouth or in the Gut? Innovation Through Implementing Oral and Gastrointestinal Health Science in Chronic Pain Management" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8812. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248812

APA StyleNijs, J., Ahmed, I., Vandeputte, D., R. Goodin, B., Adetayo, T., Kindt, S., Vanroose, M., Elma, Ö., Johansson, E., Logghe, T., Van Akeleyen, J., Goossens, Z., Labie, C., Silva, F., Lahousse, A., Huysmans, E., & Núñez-Cortés, R. (2025). In the Mouth or in the Gut? Innovation Through Implementing Oral and Gastrointestinal Health Science in Chronic Pain Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8812. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248812