Hypotension Prediction Index Software Compared with Standard Advanced Haemodynamic Monitoring in Patients Undergoing Major Aortic Surgery: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

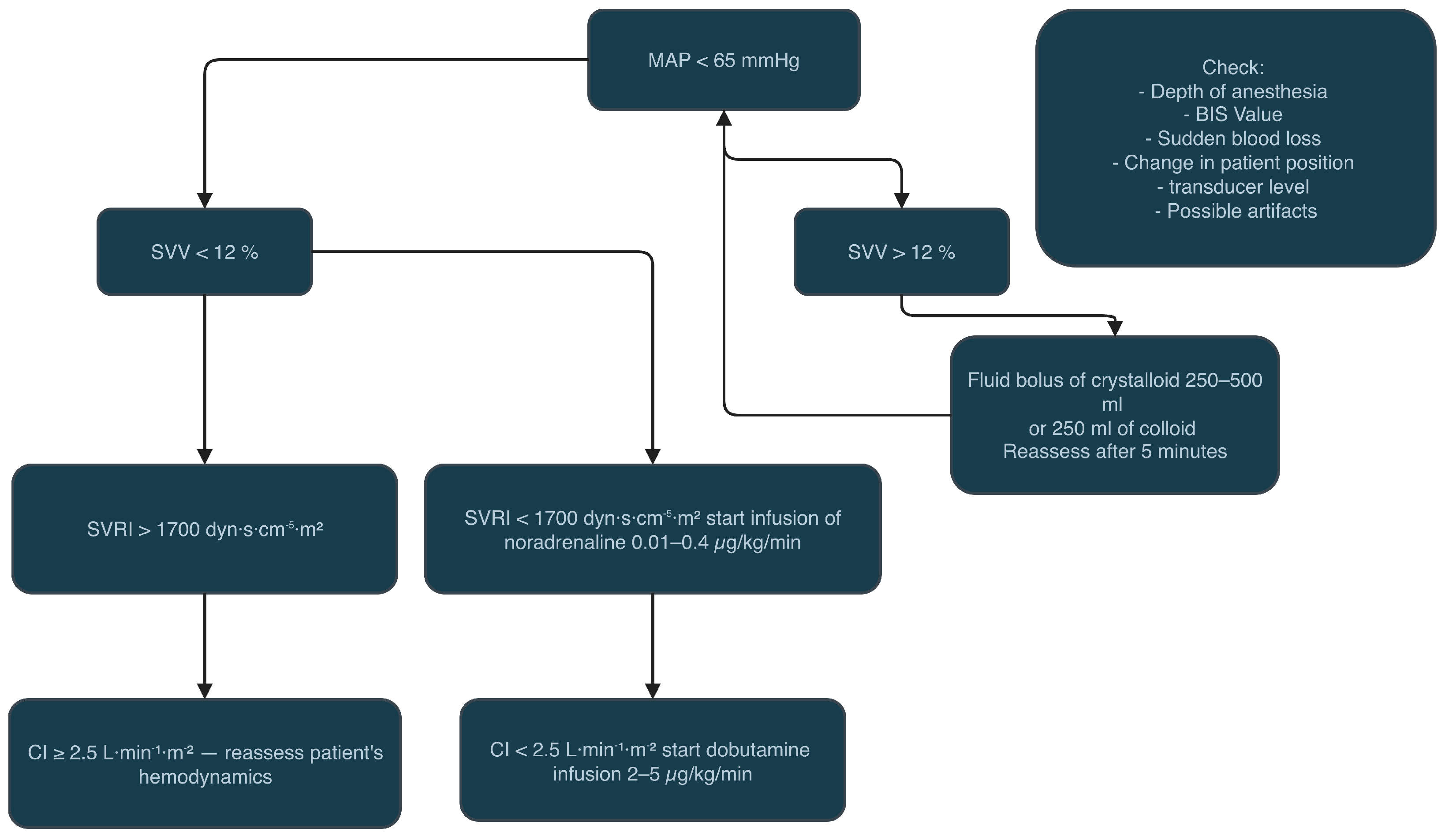

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Endpoints

2.2. Postoperative Outcomes

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Haemodynamic Management in Vascular Surgery

4.2. Clinical Interpretation of the Primary Endpoint

4.3. Benefits from the HPI Technology in Vascular and Cardiac Surgery

4.4. Lack of Benefits of the HPI Technology in Vascular and Cardiac Surgery

4.5. HPI Predictive Limitations and MAP-Based Alternatives

4.6. Unnecessary Interventions Related to HPI

4.7. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPI | Hypotension prediction index |

| IOH | Intraoperative hypotension |

| APCO | Arterial pressure cardiac output |

| GDT | Goal-directed therapy |

| MACCE | Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| MINS | Myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery |

References

- Wesselink, E.M.; Kappen, T.H.; Torn, H.M.; Slooter, A.J.; van Klei, W.A. Intraoperative hypotension and the risk of postoperative adverse outcomes: A systematic review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 121, 706–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sessler, D.I.; Khanna, A.K. Perioperative myocardial injury and the contribution of hypotension. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 44, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallqvist, L.; Martensson, J.; Granath, F.; Sahlen, A.; Bell, M. Intraoperative hypotension is associated with myocardial damage in noncardiac surgery: An observational study. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2016, 33, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Fleischmann, K.E.; Smilowitz, N.R.; de Las Fuentes, L.; Mukherjee, D.; Aggarwal, N.R.; Ahmad, F.S.; Allen, R.B.; Altin, S.E.; Auerbach, A.; et al. 2024 AHA/ACC/ACS/ASNC/HRS/SCA/SCCT/SCMR/SVM Guideline for Perioperative Cardiovascular Management for Noncardiac Surgery: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024, 150, e351–e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilowitz, N.R.; Gupta, N.; Ramakrishna, H.; Guo, Y.; Berger, J.S.; Bangalore, S. Perioperative Major Adverse Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Events Associated With Noncardiac Surgery. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilowitz, N.R.; Berger, J.S. Perioperative Cardiovascular Risk Assessment and Management for Noncardiac Surgery: A Review. JAMA 2020, 324, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, R.J.; Sutzko, D.C.; Albright, J.; Jeruzal, E.; Osborne, N.H.; Henke, P.K. Association of High Mortality With Postoperative Myocardial Infarction After Major Vascular Surgery Despite Use of Evidence-Based Therapies. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifpour, M.; Moore, L.E.; Shanks, A.M.; Didier, T.J.; Kheterpal, S.; Mashour, G.A. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of perioperative stroke in noncarotid major vascular surgery. Anesth. Analg. 2013, 116, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.A.; Wang, Y.; Berbenetz, N.M.; McConachie, I. Does goal-directed haemodynamic and fluid therapy improve peri-operative outcomes?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2018, 35, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, A.; Robba, C.; Calabrò, L.; Zambelli, D.; Iannuzzi, F.; Molinari, E.; Scarano, S.; Battaglini, D.; Baggiani, M.; De Mattei, G.; et al. Association between perioperative fluid administration and postoperative outcomes: A 20-year systematic review and a meta-analysis of randomized goal-directed trials in major visceral/noncardiac surgery. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Chai, F.; Pan, C.; Romeiser, J.L.; Gan, T.J. Effect of perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic therapy on postoperative recovery following major abdominal surgery—A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Care 2017, 21, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michard, F.; Giglio, M.T.; Brienza, N. Perioperative goal-directed therapy with uncalibrated pulse contour methods: Impact on fluid management and postoperative outcome. Br. J. Anaesth. 2017, 119, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, M.; Dalfino, L.; Puntillo, F.; Brienza, N. Hemodynamic goal-directed therapy and postoperative kidney injury: An updated meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Crit. Care 2019, 23, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, E.A.; Rhodes, A.; Landoni, G.; Galas, F.R.; Fukushima, J.T.; Park, C.H.; Almeida, J.P.; Nakamura, R.E.; Strabelli, T.M.V.; Pileggi, B.; et al. Effect of Perioperative Goal-Directed Hemodynamic Resuscitation Therapy on Outcomes Following Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial and Systematic Review. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 44, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecconi, M.; Corredor, C.; Arulkumaran, N.; Abuella, G.; Ball, J.; Grounds, R.M.; Hamilton, M.; Rhodes, A. Clinical review: Goal-directed therapy—what is the evidence in surgical patients? The effect on different risk groups. Crit. Care 2013, 17, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giglio, M.; Dalfino, L.; Puntillo, F.; Rubino, G.; Marucci, M.; Brienza, N. Haemodynamic goal-directed therapy in cardiac and vascular surgery. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 15, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, P.J.; Dierick, A.; Wilmin, S.; Bellens, B.; De Hert, S.G. A randomized controlled trial comparing an intraoperative goal-directed strategy with routine clinical practice in patients undergoing peripheral arterial surgery. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2010, 27, 788–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filiberto, A.C.; Loftus, T.J.; Elder, C.T.; Hensley, S.; Frantz, A.; Efron, P.; Ozrazgat-Baslanti, T.; Bihorac, A.; Upchurch, G.R., Jr.; Cooper, M.A. Intraoperative hypotension and complications after vascular surgery: A scoping review. Surgery 2021, 170, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhou, C.; Wang, H. Hypotension prediction index for the prevention of hypotension during surgery and critical care: A narrative review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 170, 107995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Hu, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, K. Effect of Hypotension Prediction Index in the prevention of intraoperative hypotension during noncardiac surgery: A systematic review. J. Clin. Anesth. 2022, 83, 110981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szrama, J.; Gradys, A.; Bartkowiak, T.; Woźniak, A.; Kusza, K.; Molnar, Z. Intraoperative Hypotension Prediction—A Proactive Perioperative Hemodynamic Management—A Literature Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilakouta Depaskouale, M.A.; Archonta, S.A.; Katsaros, D.M.; Paidakakos, N.A.; Dimakopoulou, A.N.; Matsota, P.K. Beyond the debut: Unpacking six years of Hypotension Prediction Index software in intraoperative hypotension prevention—A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2024, 38, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cassai, A. The Ratio of Confidence Interval Above the Minimal Clinically Important Difference. Anaesthesia 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuurmans, J.; Rellum, S.R.; Schenk, J.; van der Ster, B.J.P.; van der Ven, W.H.; Geerts, B.F.; Hollmann, M.W.; Cherpanath, T.G.V.; Lagrand, W.K.; Wynandts, P.R.; et al. Effect of a Machine Learning-Derived Early Warning Tool With Treatment Protocol on Hypotension During Cardiac Surgery and ICU Stay: The Hypotension Prediction 2 (HYPE-2) Randomized Clinical Trial. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 53, e328–e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.; Maler, S.A.; Reddy, K.; Fleming, N.W. Use of the Hypotension Prediction Index During Cardiac Surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2021, 35, 1769–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, H.; Zilahi, G. Pro: Hypotension Prediction Index—A New Tool to Predict Hypotension in Cardiac Surgery? J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2023, 37, 2133–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giustiniano, E.; Nisi, F.; Ferrod, F.; Lionetti, G.; Viscido, C.; Reda, A.; Piccioni, F.; Buono, G.; Cecconi, M. Intraoperative hemodynamic management in abdominal aortic surgery guided by the Hypotension Prediction Index: The Hemas multicentric observational study. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2025, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Turoczi, Z. Con: Hypotension Prediction Index—A New Tool to Predict Hypotension in Cardiac Surgery? J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2023, 37, 2137–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranucci, M.; Barile, L.; Ambrogi, F.; Pistuddi, V.; Surgical and Clinical Outcome Research (SCORE) Group. Discrimination and calibration properties of the hypotension probability indicator during cardiac and vascular surgery. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019, 85, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, S.; Mehilli, J.; Cassese, S.; Hall, T.S.; Abdelhamid, M.; Barbato, E.; De Hert, S.; de Laval, I.; Geisler, T.; Ibanez, B.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular assessment and management of patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3826–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vistisen, S.T.; Enevoldsen, J. CON: The Hypotension Prediction Index is not a validated predictor of hypotension. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2024, 41, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatib, F.; Jian, Z.; Buddi, S.; Lee, C.; Settels, J.; Sibert, K.; Rinehart, J.; Cannesson, M. Machine-learning algorithm to predict hypotension based on high-fidelity arterial pressure waveform analysis. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, M.M.P.; Harmannij-Markusse, M.; Donker, D.W.; Fresiello, L.; Potters, J.-W. Is Continuous Intraoperative Monitoring of Mean Arterial Pressure as Good as the Hypotension Prediction Index Algorithm?: Research Letter. Anesthesiology 2023, 138, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michard, F.; Biais, M.; Futier, E.; Romagnoli, S. Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is going to become hypotensive? Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2023, 40, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enevoldsen, J.; Hovgaard, H.L.; Vistisen, S.T. Selection Bias in the Hypotension Prediction Index: Reply. Anesthesiology 2023, 138, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouz, K.; Scheeren, T.W.L.; van den Boom, T.; Saugel, B. Hypotension Prediction Index software alarms during major noncardiac surgery: A post hoc secondary analysis of the EU-HYPROTECT registry. BJA Open 2023, 8, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, M.P.; Harmannij-Markusse, M.; Fresiello, L.; Donker, D.W.; Potters, J.W. Hypotension prediction index is equally effective in predicting intraoperative hypotension during noncardiac surgery compared to a mean arterial pressure threshold: A prospective observational study. Anesthesiology 2024, 141, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rellum, S.R.; Noteboom, S.H.; van der Ster, B.J.P.; Schuurmans, J.; Kho, E.; Vlaar, A.P.J.; Schenk, J.; Veelo, D.P. The Hypotension Prediction Index versus mean arterial pressure in predicting intraoperative hypotension. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2025, 42, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, M.S.; Longrois, D.; Columb, M.O. Hypotension prediction: Advancing the debate or retreading old ground? Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2025, 42, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szrama, J.; Gradys, A.; Nowak, Z.; Lohani, A.; Zwoliński, K.; Bartkowiak, T.; Woźniak, A.; Koszel, T.; Kusza, K. The Hypotension Prediction Index in major abdominal surgery—A prospective randomised clinical trial protocol. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2024, 43, 101417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente, J.V.; Jimenez, I.; Ripollés-Melchor, J.; Becerra, A.; Wesselink, W.; Reguant, F.; Mojarro, I.; Fuentes, M.L.A.; Abad-Motos, A.; Agudelo, E.; et al. Intraoperative haemodynamic optimisation using the Hypotension Prediction Index and its impact on tissular perfusion: A protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Fominskiy, E.V.; Turi, S.; Pruna, A.; Fresilli, S.; Triulzi, M.; Zangrillo, A.; Landoni, G. Intraoperative hypotension and postoperative outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Br. J. Anaesth. 2023, 131, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.; Fong, N.; Lazzareschi, D.; Mavrothalassitis, O.; Kothari, R.; Chen, L.L.; Pirracchio, R.; Kheterpal, S.; Domino, K.B.; Mathis, M.; et al. Fluids, vasopressors, and acute kidney injury after major abdominal surgery between 2015 and 2019: A multicentre retrospective analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 129, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Jiang, Z.; Ying, J.; Han, Y.; Chen, Z. Optimal blood pressure decreases acute kidney injury after gastrointestinal surgery in elderly hypertensive patients: A randomized study: Optimal blood pressure reduces acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Anesth. 2017, 43, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoumpa, M.; Kyttari, A.; Matiatou, S.; Tzoufi, M.; Griva, P.; Pikoulis, E.; Riga, M.; Matsota, P.; Sidiropoulou, T. The Use of the Hypotension Prediction Index Integrated in an Algorithm of Goal Directed Hemodynamic Treatment during Moderate and High-Risk Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijnberge, M.; Geerts, B.F.; Hol, L.; Lemmers, N.; Mulder, M.P.; Berge, P.; Schenk, J.; Terwindt, L.E.; Hollmann, M.W.; Vlaar, A.P.; et al. Effect of a Machine Learning-Derived Early Warning System for Intraoperative Hypotension vs. Standard Care on Depth and Duration of Intraoperative Hypotension During Elective Noncardiac Surgery: The HYPE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 323, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneck, E.; Schulte, D.; Habig, L.; Ruhrmann, S.; Edinger, F.; Markmann, M.; Habicher, M.; Rickert, M.; Koch, C.; Sander, M. Hypotension Prediction Index based protocolized haemodynamic management reduces the incidence and duration of intraoperative hypotension in primary total hip arthroplasty: A single centre feasibility randomised blinded prospective interventional trial. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2020, 34, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotoia, A.; Discenza, A.; Rauseo, M.; Matella, M.; Caggianelli, G.; Ciaramelletti, R.; Mirabella, L.; Cinnella, G. Intraoperative Hypotension during Robotic-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: A Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing Standard Goal-Directed Fluid Therapy with Hypotension Prediction Index–Guided Goal-Directed Fluid Therapy. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2025, 42, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frassanito, L.; Giuri, P.P.; Vassalli, F.; Piersanti, A.; Garcia, M.I.M.; Sonnino, C.; Zanfini, B.A.; Catarci, S.; Antonelli, M.; Draisci, G. Hypotension Prediction Index–Guided Goal-Directed Therapy and the Amount of Hypotension during Major Gynaecologic Oncologic Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2023, 37, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripollés-Melchor, J.; Tomé-Roca, J.L.; Zorrilla-Vaca, A.; Aldecoa, C.; Colomina, M.J.; Bassas-Parga, E.; Lorente, J.V.; Ruiz-Escobar, A.; Carrasco-Sánchez, L.; Sadurni-Sarda, M.; et al. Hemodynamic Management Guided by the Hypotension Prediction Index in Abdominal Surgery: A Multi-center Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesthesiology 2025, 142, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, J.; Graw, J.; Grundmann, C.D.; Komanek, T.; Wischermann, J.M.; Frey, U.H. Hypotension Prediction Index and Incidence of Perioperative Hypotension: A Single-Center Propensity-Score-Matched Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente, J.V.; Ripollés-Melchor, J.; Jiménez, I.; Becerra, A.; Wesselink, W.; Reguant, F.; Mojarro, I.; Fuentes, M.L.A.; Abad-Motos, A.; Agudelo, E.; et al. Intraoperative hemodynamic optimization using the Hypotension Prediction Index vs. goal-directed hemodynamic therapy during elective major abdominal surgery: The Predict-H multicenter randomized controlled trial. Front. Anesthesiol. 2023, 2, 1193886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, P.M.; Wulff, D.U.; Djurdjevic, M.; Korte, W.; Schnider, T.W.; Filipovic, M. Targeting Higher Intraoperative Blood Pressures Does Not Reduce Adverse Cardiovascular Events Following Noncardiac Surgery. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 1753–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcucci, M.; Painter, T.W.; Conen, D.; Lomivorotov, V.; Sessler, D.I.; Chan, M.T.V.; Borges, F.K.; Leslie, K.; Duceppe, E.; Martínez-Zapata, M.J.; et al. Hypotension-Avoidance Versus Hypertension-Avoidance Strategies in Noncardiac Surgery: An International Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | All | FloTrac | HPI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69 (65–74) | 68 (65–75) | 70 (65–73) | 0.931 |

| Female, n (%) | 23 (23%) | 13 (26%) | 10 (20%) | 0.476 |

| BMI | 24.6 (24.1–26.5) | 24.2 (24.1–26.6) | 24.7 (24.2–26.5) | 0.577 |

| Weight (kg) | 72 (65–82) | 70 (65–80.75) | 73 (65–83.5) | 0.645 |

| ASA III, n (%) | – | 45 (90%) | 45 (90%) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 82 (82%) | 43 (86%) | 39 (78%) | 0.298 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 20 (20%) | 5 (10%) | 15 (30%) | 0.012 * |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 37 (37%) | 13 (26%) | 24 (48%) | 0.023 * |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 21 (21%) | 10 (20%) | 11 (22%) | 0.806 |

| COPD, n (%) | 12 (12%) | 7 (14%) | 5 (10%) | 0.538 |

| ACEI, n (%) | 48 (49.5%) | 23 (48.9%) | 25 (50%) | 0.917 |

| ARB, n (%) | 4 (4.1%) | 3 (6.4%) | 1 (2%) | 0.352 |

| Betablocker, n (%) | 54 (55.7%) | 30 (63.8%) | 24 (48%) | 0.117 |

| Calcium-channel blocker, n (%) | 30 (30.9%) | 19 (40.4%) | 11 (22%) | 0.05 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 26 (26.8%) | 14 (29.8%) | 12 (24%) | 0.520 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 144 (112–185) | 145 (111–179) | 140 (101–185) | 0.398 |

| Monitoring time (min) | 190 (151–229) | 194 (152–230) | 178 (150–225) | 0.446 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 700 (400–1025) | 700 (500–1075) | 700 (325–1000) | 0.860 |

| Blood loss > 1000 mL, n (%) | 28 (28%) | 15 (30%) | 13 (26%) | 0.656 |

| Type of Vascular Surgery | FloTrac (n) | FloTrac (%) | HPI (n) | HPI (%) | Total (n) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aorto-Bifemoral Bifurcated Graft | 25 | 50.0 | 19 | 38.0 | 44 | 44.0 |

| Straight Aortic Graft | 10 | 20.0 | 19 | 38.0 | 29 | 29.0 |

| Aorto-Bi-Iliac Bifurcated Graft | 4 | 8.0 | 4 | 8.0 | 8 | 8.0 |

| Graft Replacement | 3 | 6.0 | 3 | 6.0 | 6 | 6.0 |

| Thoracoabdominal Endovascular Graft (T-branch) | 4 | 8.0 | 2 | 4.0 | 6 | 6.0 |

| Aorto-Femoral Bypass | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair (TEVAR) | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Other | 2 | 4.0 | 3 | 6.0 | 5 | 5.0 |

| Parameter | FloTrac (Median [IQR]) | HPI (Median [IQR]) | 95% CI (for Difference = FloTrac − HPI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noradrenaline max dose [µg/kg/min] | 0.12 (0.10–0.20) | 0.15 (0.10–0.24) | [−0.06; 0.00] | 0.136 |

| Noradrenaline infusion time [min] | 115 (63 – 166) | 121.5 (59–155.5) | [−33.00; 30.00] | 0.920 |

| Dobutamine max dose [µg/kg/min] | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–5.00) | [−0.00; 0.00] | 0.050 |

| Dobutamine infusion time [min] | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–45.00) | [−0.00; 0.00] | 0.078 |

| Crystalloids [mL] | 1200 (1000–1500) | 1500 (1000–1975) | [−500; 0] | 0.144 |

| Total fluids [mL] | 2000 (1500–2500) | 2000 (1500–2500) | [−250; 250] | 1.000 |

| RBC transfused [units] | 0.00 (0.00–2.00) | 0.00 (0.00–2.00) | NA | 0.725 |

| FFP transfused [units] | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–2.00) | NA | 0.229 |

| Parameter | All | FloTrac | HPI | p-Value | p-Value (Holm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative MAP | 100.5 (91–110) | 99.5 (88–115.5) | 101.5 (92–109.75) | 0.495 | 0.990 |

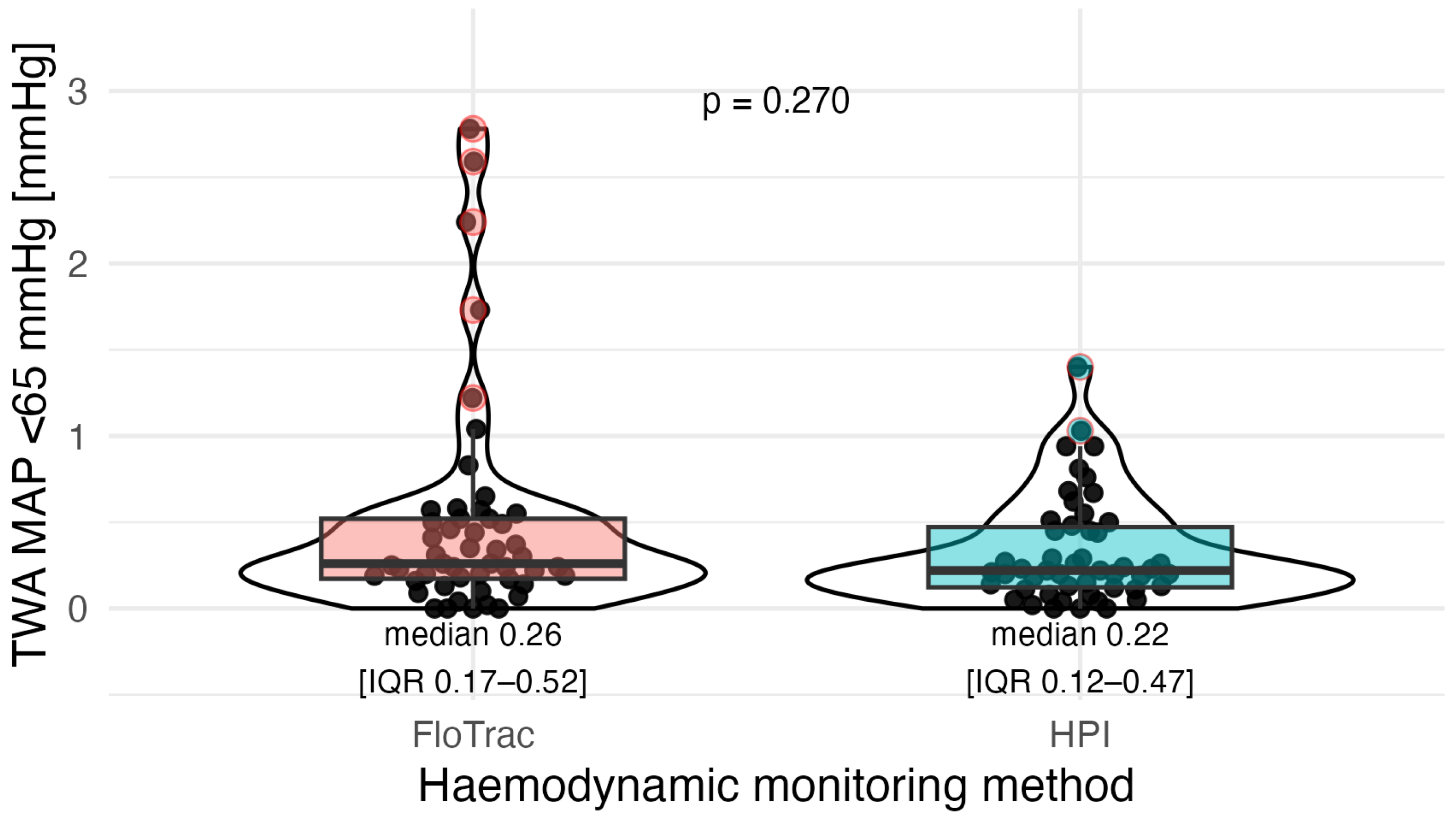

| TWA-MAP < 65 mmHg | 0.24 (0.14–0.50) | 0.26 (0.17–0.52) | 0.22 (0.12–0.47) | 0.270 | 0.810 |

| Area under 65 mmHg (mmHg·min) | 48.7 (26.6–98.4) | 55.3 (33.4–116.9) | 38.3 (18.6–83.4) | 0.090 | 0.450 |

| Episodes of hypotension | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) | 3.5 (2.0–5.0) | 3.0 (1.25–4.75) | 0.154 | 0.616 |

| Total hypotension time (min) | 8 (3–14) | 10 (5–15) | 5 (2–11) | 0.030 * | 0.180 |

| Mean episode duration (min) | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.020 * | 0.140 |

| Episodes of MAP < 50 mmHg | 0 (0–0.25) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0.562 | 0.990 |

| Parameter | All | FloTrac | HPI | p-Value | p-Value (Holm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP > 90 mmHg (min) | 55 (37–81) | 49 (28–81) | 62 (49–81) | 0.046 * | 0.066 |

| MAP > 90 mmHg (% of time) | 34 (18–46) | 25 (15–40) | 38 (26–52) | 0.006 * | 0.036 ** |

| MAP > 100 mmHg (min) | 26 (11–42) | 16 (8–36) | 31 (18–42) | 0.022 * | 0.066 |

| MAP > 100 mmHg (% of time) | 13 (6–24) | 9 (4–20) | 18 (9–29) | 0.006 * | 0.036 ** |

| TWA > 90 mmHg | 3.13 (1.92–4.41) | 2.42 (1.30–5.23) | 4.04 (2.79–7.10) | 0.013 * | 0.052 |

| TWA > 100 mmHg | 1.21 (0.68–1.80) | 0.98 (0.31–2.23) | 1.61 (0.81–3.02) | 0.027 * | 0.066 |

| Outcome | FloTrac | HPI | RR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKI | 19/49 (38.8%) | 15/50 (30.0%) | 0.77 (0.45–1.34) | 0.358 |

| MINS | 5/47 (10.6%) | 12/49 (24.5%) | 2.30 (0.88–6.03) | 0.076 |

| Circulatory Failure | 9/50 (18.0%) | 10/50 (20.0%) | 1.11 (0.49–2.50) | 0.799 |

| Stroke | 0/50 (0.0%) | 1/50 (2.0%) | — | 1.000 |

| Respiratory Failure | 5/50 (10.0%) | 4/50 (8.0%) | 0.80 (0.23–2.81) | 1.000 |

| Reoperation | 11/50 (22.0%) | 8/50 (16.0%) | 0.73 (0.32–1.65) | 0.444 |

| Surgical Complications | 10/50 (20.0%) | 9/50 (18.0%) | 0.90 (0.40–2.02) | 0.799 |

| Mortality | 2/50 (4.0%) | 4/50 (8.0%) | 2.00 (0.38–10.43) | 0.678 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szrama, J.; Gezela, M.; Żurański, Ł.; Kulas, K.; Gajda, M.; Smuszkiewicz, P.; Sobczyński, P. Hypotension Prediction Index Software Compared with Standard Advanced Haemodynamic Monitoring in Patients Undergoing Major Aortic Surgery: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248791

Szrama J, Gezela M, Żurański Ł, Kulas K, Gajda M, Smuszkiewicz P, Sobczyński P. Hypotension Prediction Index Software Compared with Standard Advanced Haemodynamic Monitoring in Patients Undergoing Major Aortic Surgery: A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248791

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzrama, Jakub, Mariusz Gezela, Łukasz Żurański, Katarzyna Kulas, Michał Gajda, Piotr Smuszkiewicz, and Paweł Sobczyński. 2025. "Hypotension Prediction Index Software Compared with Standard Advanced Haemodynamic Monitoring in Patients Undergoing Major Aortic Surgery: A Retrospective Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248791

APA StyleSzrama, J., Gezela, M., Żurański, Ł., Kulas, K., Gajda, M., Smuszkiewicz, P., & Sobczyński, P. (2025). Hypotension Prediction Index Software Compared with Standard Advanced Haemodynamic Monitoring in Patients Undergoing Major Aortic Surgery: A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8791. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248791