Thrombus Composition and the Evolving Role of Tenecteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke

Abstract

1. Introduction

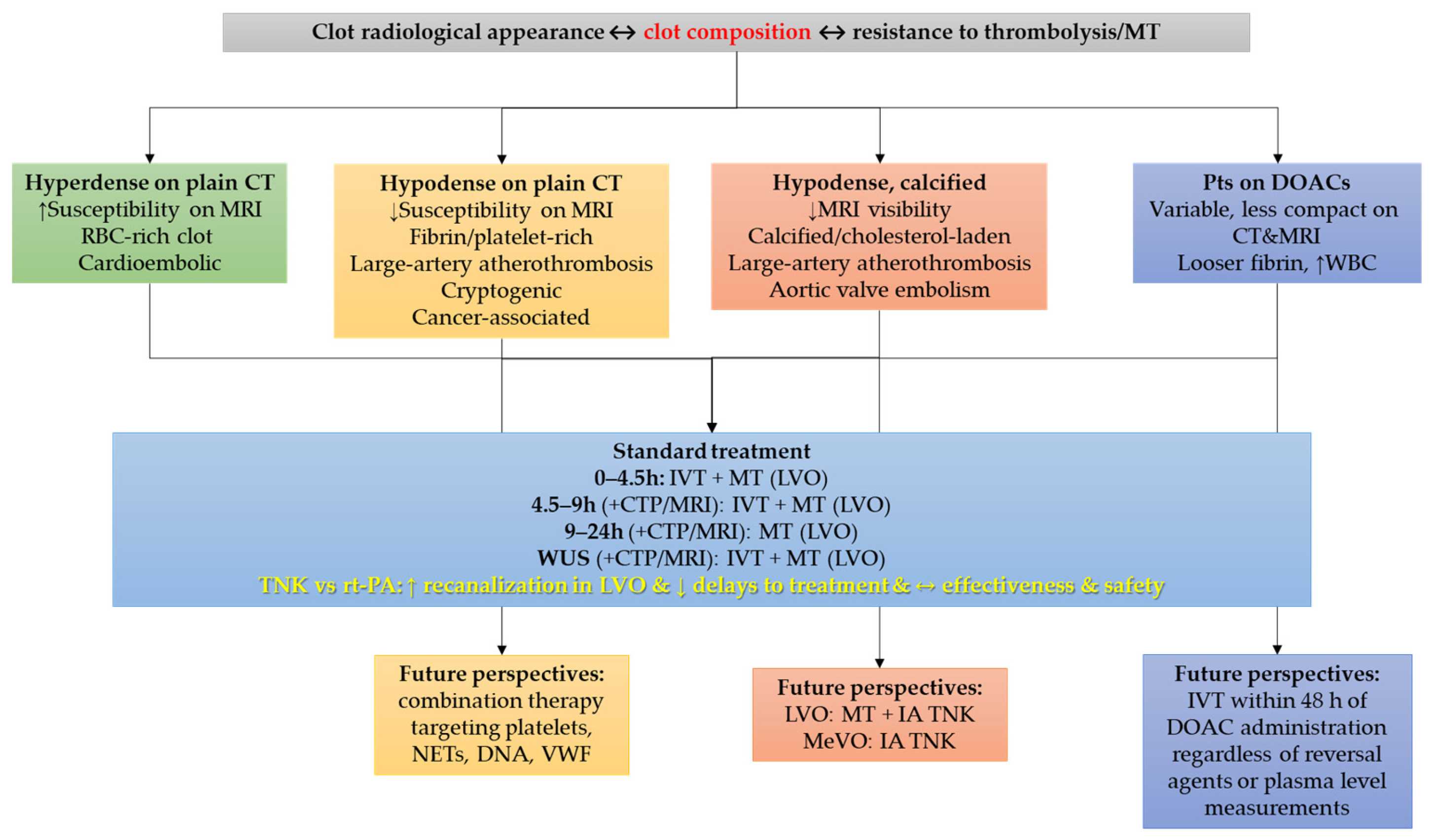

2. Current Approaches in Acute Ischemic Stroke Management

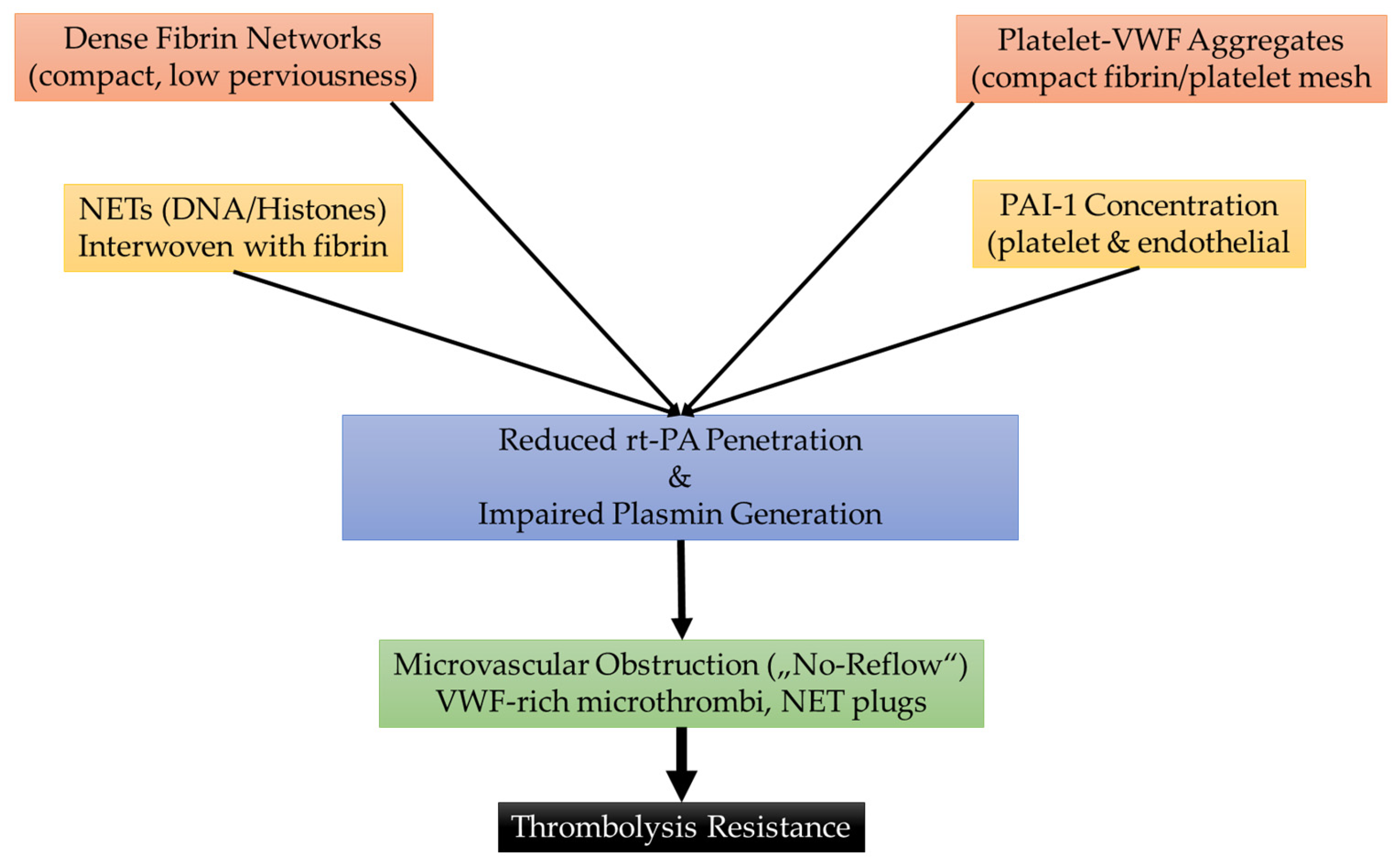

3. Thrombus Composition and Resistance to Treatment

4. Challenges and Opportunities in Direct Oral Anticoagulant-Treated Patients

5. The Promise of Tenecteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke

6. Combination Therapies to Enhance Thrombolysis and Mechanical Thrombectomy

7. Synergic Therapies to Achieve Reperfusion

8. Future Perspectives

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIS | Acute ischemic stroke |

| CT | Computerized tomography |

| CTA | Computerized tomography angiography |

| CTP | Computerized tomography perfusion |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DNT | Door-needle time |

| DOAC | Direct oral anticoagulant |

| GRE | Gradient recalled echo |

| IA | Intra-arterial |

| IV | Intravenous |

| IVT | Intravenous thrombolysis |

| LVO | Large vessel occlusion |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MT | Mechanical thrombectomy |

| NET | Neutrophil extracellular trap |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| RBCs | Red blood cells |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| rt-PA | Alteplase |

| sICH | Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage |

| SWI | Susceptibility-weighted imaging |

| TNK | Tenecteplase |

| VWF | Von Willebrand factor |

References

- Berge, E.; Whiteley, W.; Audebert, H.; De Marchis, G.M.; Fonseca, A.C.; Padiglioni, C.; de la Ossa, N.P.; Strbian, D.; Tsivgoulis, G.; Turc, G. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur. Stroke J. 2021, 6, I–LXII. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, W.J.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Ackerson, T.; Adeoye, O.M.; Bambakidis, N.C.; Becker, K.; Biller, J.; Brown, M.; Demaerschalk, B.M.; Hoh, B.; et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019, 50, e344–e418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Sun, H.; Xing, Y. Hemorrhagic transformation after cerebral infarction: Current concepts and challenges. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014, 2, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Shi, K.; Wang, Y.; Shi, F.D. Neurovascular Inflammation and Complications of Thrombolysis Therapy in Stroke. Stroke 2023, 54, 2688–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desilles, J.P.; Di Meglio, L.; Delvoye, F.; Maïer, B.; Piotin, M.; Ho-Tin-Noé, B.; Mazighi, M. Composition and Organization of Acute Ischemic Stroke Thrombus: A Wealth of Information for Future Thrombolytic Strategies. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 870331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Tin-Noé, B.; Desilles, J.P.; Mazighi, M. Thrombus composition and thrombolysis resistance in stroke. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 7, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohle, E.; Ashok, A.H.; Bhakta, S.; Induruwa, I.; Evans, N.R. Thrombus composition in ischaemic stroke: Histological and radiological evaluation, and implications for acute clinical management. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2025, 58, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporns, P.B.; Hanning, U.; Schwindt, W.; Velasco, A.; Minnerup, J.; Zoubi, T.; Heindel, W.; Jeibmann, A.; Niederstadt, T.U. Ischemic stroke: What does the histological composition tell us about the origin of the thrombus? Stroke 2017, 48, 2206–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hund, H.M.; Boodt, N.; Hansen, D.; Haffmans, W.A.; Lycklama À Nijeholt, G.J.; Hofmeijer, J.; Dippel, D.W.J.; van der Lugt, A.; van Es, A.C.G.M.; van Beusekom, H.M.M. Association between thrombus composition and stroke etiology in the Mr Clean registry biobank. Neuroradiology 2023, 65, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staessens, S.; Denorme, F.; Francois, O.; Desender, L.; Dewaele, T.; Vanacker, P.; Deckmyn, H.; Vanhoorelbeke, K.; Andersson, T.; De Meyer, S.F. Structural analysis of ischemic stroke thrombi: Histological indications for therapy resistance. Haematologica 2020, 105, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu LaGrange, D.; Reymond, P.; Brina, O.; Zboray, R.; Neels, A.; Wanke, I.; Lövblad, K.O. Spatial heterogeneity of occlusive thrombus in acute ischemic stroke: A systematic review. J. Neuroradiol. 2023, 50, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, T.R.; Fricano, S.; Waqas, M.; Tso, M.; Dmytriw, A.A.; Mokin, M.; Kolega, J.; Tomaszewski, J.; Levy, E.I.; Davies, J.M.; et al. Increased Perviousness on CT for Acute Ischemic Stroke is Associated with Fibrin/Platelet-Rich Clots. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmforth, C.; Whittington, B.; Tzolos, E.; Bing, R.; Williams, M.C.; Clark, L.; Corral, C.A.; Tavares, A.; Dweck, M.R.; Newby, D.E. Translational molecular imaging: Thrombosis imaging with positron emission tomography. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2024, 39, 101848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolugbo, P.; Ariëns, R.A.S. Thrombus Composition and Efficacy of Thrombolysis and Thrombectomy in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2021, 52, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zidansek, A.; Blinc, A. The influence of transport parameters and enzyme kinetics of the fibrinolytic system on thrombolysis: Mathematical modelling of two idealised cases. Thromb. Haemost. 1991, 65, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinel, T.R.; Wilson, D.; Gensicke, H.; Scheitz, J.F.; Ringleb, P.; Goganau, I.; Kaesmacher, J.; Bae, H.J.; Kim, D.Y.; Kermer, P.; et al. Intravenous Thrombolysis in Patients With Ischemic Stroke and Recent Ingestion of Direct Oral Anticoagulants. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bücke, P.; Jung, S.; Kaesmacher, J.; Goeldlin, M.B.; Horvath, T.; Prange, U.; Beyeler, M.; Fischer, U.; Arnold, M.; Seiffge, D.J.; et al. Intravenous thrombolysis in patients with recent intake of direct oral anticoagulants: A target trial analysis after the liberalization of institutional guidelines. Eur. Stroke J. 2024, 9, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, W.; Holmes, D.N.; Hernandez, A.F.; Saver, J.L.; Fonarow, G.C.; Smith, E.E.; Bhatt, D.L.; Schwamm, L.H.; Reeves, M.J.; Matsouaka, R.A.; et al. Association of Recent Use of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants With Intracranial Hemorrhage Among Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Treated With Alteplase. JAMA 2022, 327, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenberg, B.; Boeckh-Behrens, T.; Maegerlein, C.; Härtl, J.; Hernandez Petzsche, M.; Zimmer, C.; Wunderlich, S.; Berndt, M. Ischemic Stroke of Suspected Cardioembolic Origin Despite Anticoagulation: Does Thrombus Analysis Help to Clarify Etiology? Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 824792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretnar Oblak, J.; Sabovic, M.; Frol, S. Intravenous Thrombolysis After Idarucizumab Application in Acute Stroke Patients-A Potentially Increased Sensitivity of Thrombi to Lysis? J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2019, 28, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craik, C.S.; Page, M.J.; Madison, E.L. Proteases as therapeutics. Biochem. J. 2011, 435, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyt, B.A.; Paoni, N.F.; Refino, C.J.; Berleau, L.; Nguyen, H.; Chow, A.; Lai, J.; Peña, L.; Pater, C.; Ogez, J.; et al. A faster-acting and more potent form of tissue plasminogen activator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 3670–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.E.; Warach, S.J. Evolving Thrombolytics: From Alteplase to Tenecteplase. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Moreton, F.C.; Kalladka, D.; Cheripelli, B.K.; MacIsaac, R.; Tait, R.C.; Muir, K.W. Coagulation and Fibrinolytic Activity of Tenecteplase and Alteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2015, 46, 3543–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.; Emborski, R.; Diioia, A.; Stone, D.; Stupca, K. Improved Door-to-Needle Time After Implementation of Tenecteplase as the Preferred Thrombolytic for Acute Ischemic Stroke at a Large Community Teaching Hospital Emergency Department. Hosp. Pharm. 2024, 11, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekita, A.; Siedler, G.; Sembill, J.A.; Schmidt, M.; Singer, L.; Kallmuenzer, B.; Mers, L.; Bogdanova, A.; Schwab, S.; Gerner, S.T. Switch to tenecteplase for intravenous thrombolysis in stroke patients: Experience from a German high-volume stroke center. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2025, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Thon, J.M.; Heslin, M.; Thau, L.; Yeager, T.; Siegal, T.; Vigilante, N.; Kamen, S.; Tiongson, J.; Jovin, T.G.; et al. Tenecteplase Improves Door-to-Needle Time in Real-World Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke Vasc. Interv. Neurol. 2021, 1, e000102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Spratt, N.; Bivard, A.; Campbell, B.; Chung, K.; Miteff, F.; O’Brien, B.; Bladin, C.; McElduff, P.; Allen, C.; et al. A randomized trial of tenecteplase versus alteplase for acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Cheripelli, B.K.; Lloyd, S.M.; Kalladka, D.; Moreton, F.C.; Siddiqui, A.; Ford, I.; Muir, K.W. Alteplase versus tenecteplase for thrombolysis after ischaemic stroke (ATTEST): A phase 2, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint study. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logallo, N.; Novotny, V.; Assmus, J.; Kvistad, C.E.; Alteheld, L.; Rønning, O.M.; Thommessen, B.; Amthor, K.F.; Ihle-Hansen, H.; Kurz, M.; et al. Tenecteplase versus alteplase for management of acute ischaemic stroke (NOR-TEST): A phase 3, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Sui, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Du, W.; et al. Safety and efficacy of tenecteplase versus alteplase in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (TRACE): A multicentre, randomised, open label, blinded-endpoint (PROBE) controlled phase II study. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2022, 7, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, B.K.; Buck, B.H.; Singh, N.; Deschaintre, Y.; Almekhlafi, M.A.; Coutts, S.B.; Thirunavukkarasu, S.; Khosravani, H.; Appireddy, R.; Moreau, F.; et al. AcT Trial Investigators. Intravenous tenecteplase compared with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in Canada (AcT): A pragmatic, multicentre, open-label, registry-linked, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2022, 400, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Pan, Y.; Li, H.; Parsons, M.W.; Campbell, B.C.V.; Schwamm, L.H.; Fisher, M.; Che, F.; Dai, H.; et al. TRACE-2 Investigators. Tenecteplase versus alteplase in acute ischaemic cerebrovascular events (TRACE-2): A phase 3, multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, S.; Dai, H.; Lu, G.; Wang, W.; Che, F.; Geng, Y.; Sun, M.; Li, X.; Li, H.; et al. Tenecteplase vs. Alteplase for Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: The ORIGINAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 332, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, M.W.; Yogendrakumar, V.; Churilov, L.; Garcia-Esperon, C.; Campbell, B.C.V.; Russell, M.L.; Sharma, G.; Chen, C.; Lin, L.; Chew, B.L.; et al. TASTE Investigators. Tenecteplase versus alteplase for thrombolysis in patients selected by use of perfusion imaging within 4·5 h of onset of ischaemic stroke (TASTE): A multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, K.W.; Ford, G.A.; Ford, I.; Wardlaw, J.M.; McConnachie, A.; Greenlaw, N.; Mair, G.; Sprigg, N.; Price, C.I.; MacLeod, M.J.; et al. Tenecteplase versus alteplase for acute stroke within 4·5 h of onset (ATTEST-2): A randomised, parallel group, open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.C.V.; Mitchell, P.J.; Churilov, L.; Yassi, N.; Kleinig, T.J.; Dowling, R.J.; Yan, B.; Bush, S.J.; Dewey, H.M.; Thijs, V.; et al. EXTEND-IA TNK Investigators. Tenecteplase versus Alteplase before Thrombectomy for Ischemic Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, G.W.; Jumaa, M.; Purdon, B.; Zaidi, S.F.; Streib, C.; Shuaib, A.; Sangha, N.; Kim, M.; Froehler, M.T.; Schwartz, N.E.; et al. TIMELESS Investigators. Tenecteplase for Stroke at 4.5 to 24 Hours with Perfusion-Imaging Selection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvistad, C.E.; Næss, H.; Helleberg, B.H.; Idicula, T.; Hagberg, G.; Nordby, L.M.; Jenssen, K.N.; Tobro, H.; Rörholt, D.M.; Kaur, K.; et al. Tenecteplase versus alteplase for the management of acute ischaemic stroke in Norway (NOR-TEST 2, part A): A phase 3, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skärlund, M.; Åsberg, S.; Eriksson, M.; Lundström, E. Tenecteplase compared to alteplase in real-world outcome: A Swedish Stroke Register study. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2024, 129, e10459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.R.; Hill, T.P.; Paul, K.; Talbott, M.; Golovko, G.; Shaltoni, H.; Jehle, D. Tenecteplase Versus Alteplase for Acute Stroke: Mortality and Bleeding Complications. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2023, 82, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Cai, L.; Ying, Y.; Yang, J. Real-world data of tenecteplase vs. alteplase in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke: A single-center analysis. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1386386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, R.; Liu, Y. Comparative effectiveness and safety of tenecteplase versus alteplase for intravenous thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: A retrospective study. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1691168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, J.F.; Weber, J.M.; Alhanti, B.; Saver, J.L.; Messé, S.R.; Schwamm, L.H.; Fonarow, G.C.; Sheth, K.N.; Smith, E.E.; Mullen, M.T.; et al. Short-Term Safety and Effectiveness for Tenecteplase and Alteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e250548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsivgoulis, G.; Katsanos, A.H.; Christogiannis, C.; Faouzi, B.; Mavridis, D.; Dixit, A.K.; Palaiodimou, L.; Khurana, D.; Petruzzellis, M.; Psychogios, K.; et al. Intravenous Thrombolysis with Tenecteplase for the Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Ann. Neurol. 2022, 92, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renú, A.; Millán, M.; San Román, L.; Blasco, J.; Martí-Fàbregas, J.; Terceño, M.; Amaro, S.; Serena, J.; Urra, X.; Laredo, C.; et al. CHOICE Investigators. Effect of intra-arterial alteplase vs. placebo following successful thrombectomy on functional outcomes in patients with large vessel occlusion acute ischemic stroke. JAMA 2022, 327, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Vargas, M.; Courson, J.; Gardea, L.; Sen, M.; Yee, A.; Rumbaut, R.; Cruz, M.A. The impact of von Willebrand factor on fibrin formation and structure unveiled with type 3 von Willebrand disease plasma. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2024, 35, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiq, F.; O’Donnell, J.S. Novel functions for von Willebrand factor. Blood 2024, 144, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogendrakumar, V.; Vandelanotte, S.; Mistry, E.A.; Hill, M.D.; Coutts, S.B.; Nogueira, R.G.; Nguyen, T.N.; Medcalf, R.L.; Broderick, J.P.; De Meyer, S.F.; et al. Emerging Adjuvant Thrombolytic Therapies for Acute Ischemic Stroke Reperfusion. Stroke 2024, 55, 2536–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandelanotte, S.; François, O.; Desender, L.; Staessens, S.; Vanhoorne, A.; Van Gool, F.; Tersteeg, C.; Vanhoorelbeke, K.; Vanacker, P.; Andersson, T.; et al. R-tPA resistance is specific for platelet-rich stroke thrombi and can be overcome by targeting nonfibrin components. Stroke 2024, 55, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meglio, L.; Desilles, J.P.; Ollivier, V.; Nomenjanahary, M.S.; Di Meglio, S.; Deschildre, C.; Loyau, S.; Olivot, J.M.; Blanc, R.; Piotin, M.; et al. Acute ischemic stroke thrombi have an outer shell that impairs fibrinolysis. Neurology 2019, 93, e1686–e1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengozzi, L.; Barison, I.; Malý, M.; Lorenzoni, G.; Fedrigo, M.; Castellani, C.; Gregori, D.; Malý, P.; Matěj, R.; Toušek, P.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Thrombolysis Resistance: New Insights for Targeting Therapies. Stroke 2024, 55, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desilles, J.-P.; Nomenjanahary, M.S.; Perrot, A.; Di Meglio, L.; Zemali, F.; Zalghout, S.; Loyau, S.; Labreuche, J.; Bourrienne, M.-C.; Faille, D.; et al. The compoCLOT Study Group. Neutrophil extracellular traps block endogenous and intravenous thrombolysis-induced fibrinolysis in large vessel occlusion acute ischemic stroke. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, M.; Longstaff, C. Extracellular Histones Inhibit Fibrinolysis through Noncovalent and Covalent Interactions with Fibrin. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 121, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Wu, H.; Lin, B.; Deng, D.; Liu, Y.; Qu, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, B. Targeting Neutrophil Extracellular Traps: A New Strategy for the Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke Based on Thrombolysis Resistance. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2025; online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ye, J.; Li, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Tan, S.; Hu, B.; Jin, H. The role of neutrophils in tPA thrombolysis after stroke: A malicious troublemaker. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1477669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pancioli, A.M.; Adeoye, O.; Schmit, P.A.; Khoury, J.; Levine, S.R.; Tomsick, T.A.; Sucharew, H.; Brooks, C.E.; Crocco, T.J.; Gutmann, L.; et al. Combined approach to lysis utilizing eptifibatide and recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke-enhanced regimen stroke trial. Stroke 2013, 44, 2381–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, A.D.; Alexandrov, A.V.; Lyden, P.; Lee, J.; Martin-Schild, S.; Shen, L.; Wu, T.C.; Sisson, A.; Pandurengan, R.; Chen, Z.; et al. The argatroban and tissue-type plasminogen activator stroke study: Final results of a pilot safety study. Stroke 2012, 43, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Treurniet, K.M.; Chen, W.; Peng, Y.; Han, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; et al. Endovascular Thrombectomy with or without Intravenous Alteplase in Acute Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1981–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, W.; Qiu, Z.; Li, F.; Sang, H.; Wu, D.; Luo, W.; Liu, S.; Yuan, J.; Song, J.; Shi, Z. Effect of Endovascular Treatment Alone vs. Intravenous Alteplase Plus Endovascular Treatment on Functional Independence in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: The DEVT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, U.; Kaesmacher, J.; Strbian, D.; Eker, O.; Cognard, C.; Plattner, P.S.; Bütikofer, L.; Mordasini, P.; Deppeler, S.; Pereira, V.M.; et al. Thrombectomy alone versus intravenous alteplase plus thrombectomy in patients with stroke: An open-label, blinded-outcome, randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2022, 400, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCouffe, N.E.; Kappelhof, M.; Treurniet, K.M.; Rinkel, L.A.; Bruggeman, A.E.; Berkhemer, O.A.; Wolff, L.; van Voorst, H.; Tolhuisen, M.L.; Dippel, D.W.J.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Intravenous Alteplase before Endovascular Treatment for Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, L.C.; Bergmann, F.; Hosmann, A.; Greisenegger, S.; Kammerer, K.; Jilma, B.; Siller-Matula, J.M.; Zeitlinger, M.; Gelbenegger, G.; Jorda, A. Endovascular thrombectomy with or without intravenous thrombolysis in large-vessel ischemic stroke: A non-inferiority meta-analysis of 6 randomised controlled trials. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2023, 150, 107177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaesmacher, J.; Cavalcante, F.; Kappelhof, M.; Treurniet, K.M.; Rinkel, L.; Liu, J.; Yan, B.; Zi, W.; Kimura, K.; Eker, O.F.; et al. Time to Treatment With Intravenous Thrombolysis Before Thrombectomy and Functional Outcomes in Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2024, 31, 764–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frol, S.; Cortez, G.; Pretnar Oblak, J.; Papanagiotou, P.; Levy, E.I.; Siddiqui, A.H.; Chapot, R. The evolution of tenecteplase as a bridging agent for acute ischemic stroke. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2025, 17, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Thrombus Type | Key Features | Imaging Correlates | Treatment Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBC-rich | Loose fibrin network, high RBC content | Hyperdense artery sign on CT; susceptibility vessel sign on MRI | Good response to IVT and MT; often easier retrieval |

| Fibrin/Platelet-rich | Dense fibrin, abundant platelets, intermeshed NETs/DNA | Low-density clot on CT; less prominent susceptibility on MRI | Poor IVT response; resistant to MT, often requires multiple passes |

| Calcified/Cholesterol-laden | Rigid structure, calcium or cholesterol crystals present | Hypodense/calcified appearance on CT; poor visibility on MRI | Highly resistant to IVT and MT; difficult or incomplete retrieval |

| In patients on DOACs | Looser fibrin network, thicker strands, ↑ WBC content | Variable; may appear less compact on CT/MRI | Potentially more susceptible to IVT; favorable outcomes observed in MT |

| RCT (Year) | Phase | N | TNK Dose | Key Population | Primary Outcome (mRS 0–1 at 90 d Unless Stated) | Functional Outcome (TNK vs. rt-PA) mRS 0–1 | sICH | Mortality | DNT (Min, Median) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parsons et al. (2012) [28] | 2 | 75 | 0.1 and 0.25 mg/kg | AIS with perfusion lesion within 6 h of symptom onset, no MT | Reperfusion at 24 h: 79% vs. 55% (p = 0.004) NIHSS improvement at 24 h: ↓ 8 vs. ↓ 3 | 54% vs. 40% (p = 0.25) | 4% vs. 12% (p = 0.33) | 8% vs. 12% (p = 0.68) | NA | TNK with significantly better reperfusion and NIHSS improvement compared with rt-PA |

| ATTEST (2015) [29] | 2 | 104 | 0.25 mg/kg | AIS within 4.5 h of symptom onset, no MT | % penumbral salvage: 68% in either group (p = 0.81) | 28% vs. 20% (p = 0.28) | 2% vs. 4% (p = 0.55) | 17% vs. 12% (p = 0.51) | 42 vs. 38 | TNK and rt-PA with similar neurological and neuroradiological outcomes |

| NOR-TEST (2017) [30] | 3 | 1100 | 0.4 mg/kg | AIS (mild, median NIHSS 4) within 4.5 h of symptom onset or 4.5 h of awakening with symptoms, MT allowed | mRS 0–1 at 90 d | 64% vs. 63% (p = 0.52) | 3% vs. 2% (p = 0.70) | 5% vs. 5% (p = 0.68) | 32 vs. 34 | TNK not superior to rt-PA &similar safety |

| EXTEND-IA TNK (2018) [37] | 2 | 202 | 0.25 mg/kg | AIS with LVOs within 4.5 h of symptom onset, MT-eligible pts | Reperfusion > 50% on initial angiogram: TNK superior to rt-PA for excellent reperfusion (22% vs. 10%) (p = 0.002 for noninferiority; p = 0.03 for superiority) | 51% vs. 43% (p = 0.23) | 1% vs. 1% (p = 0.99) | 10% vs. 18% (p = 0.08) | NA | TNK superior to rt-PA in restoring perfusion in the territory of a proximal-cerebral artery occlusion |

| TRACE (2022) [31] | 2 | 236 | 0.1, 0.25, 0.32 mg/kg | AIS within 3 h of symptom onset in Chinese, MT allowed but excluded from PPA | NIHSS ↓ ≥ 4 or ≤1 at day 14: TNK 0.1 mg: 63% vs. TNK 0.25 mg: 77% vs. TNK 0.32 mg: 67% vs. rt-PA: 63% | TNK 0.1 mg: 55% vs. TNK 0.25 mg: 64% vs. TNK 0.32 mg: 62% vs. rt-PA: 59% | TNK 0.1 mg: 5% vs. TNK 0.25 mg: 0% vs. TNK 0.32 mg: 3.3% vs. rt-PA: 1.7 (p = 0.52) | TNK 0.1 mg: 10% vs. TNK 0.25 mg: 1.8% vs. TNK 0.32 mg: 8.3% vs. rt-PA: 10.2% | TNK 0.1 mg: 71 vs. TNK 0.25 mg: 60 vs. TNK 0.32 mg: 69 vs. rt-PA: 71 | TNK at all doses well tolerated |

| NOR-TEST 2 (2022) [39] | 3 | 204 | 0.4 mg/kg | Moderate-severe AIS (NIHSS ≥ 6) within 4.5 h of symptom onset, MT allowed | mRS 0–1 at 90 d | 32% vs. 51% (p = 0.0064) | 6% vs. 1% (p = 0.061) | 16% vs. 6% (p = 0.013) | NA | TNK 0.4 mg/kg worse safety and functional outcomes compared to rt-PA 0.9 mg/kg |

| AcT (2022) [32] | 3 | 1577 | 0.25 mg/kg | AIS within 4.5 h of symptom onset meeting standard IVT criteria, MT allowed | mRS 0–1 at 90 d | 37% vs. 35% | 3.4% vs. 3.2% | 15.3% vs. 15.4% | 36 vs. 37 | TNK reasonable alternative to rt-PA |

| TRACE-2 (2023) [33] | 3 | 1417 | 0.25 mg/kg | Moderate-severe AIS (NIHSS 5-25) within 4.5 h of symptom onset, Chinese, ineligible for MT | mRS 0–1 at 90 d | 62% vs. 58% | 2% vs. 2% | 7% vs. 5% | 58 vs. 61 | TNK non-inferior to rt-PA |

| ORIGINAL (2024) [34] | 3 | 1465 | AIS, Chinese, within 4.5 h of symptom onset, MT allowed | mRS 0–1 at 90 d | 73% vs. 70% | 1.2% vs. 1.2% | 4.6% vs. 5.8% | NA | TNK non-inferior to rt-PA, similar safety | |

| TASTE (2024) [35] | 3 | 680 | AIS, within 4.5 h of symptom onset, selected by CTP, no MT | mRS 0–1 at 90 d | 57% vs. 55% (p = 0.031 for non-inferiority) | 3% vs. 2% | 7% vs. 4% | 65 vs. 64 | TNK non-inferior to rt-PA in PPP, not in ITT analysis | |

| ATTEST-2 (2024) [36] | 3 | 1777 | 0.25 mg/kg | Moderate-severe AIS (NIHSS ≥ 6) within 4.5 h of symptom onset, MT allowed | mRS 0–1 at 90 d | 44% vs. 42% (p = 0.0018 for non-inferiority, 0.40 for superiority) | 2% vs. 2% (p = 0.37) | 8% vs. 8% (p = 0.80) | 47 vs. 46 | TNK non-inferior to rt-PA |

| RWS (Year) | Design | N (TNK/rt-PA) | Functional Outcome (mRS 0–2 at 90 d Unless Stated) | sICH Rate | Mortality | DNT (Min) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsivgoulis et al. (2022) [45] | Prospectively collected data from SITS-ISTR | 331/797 MT: 7%/5% PSMG | 68% vs. 52% (p < 0.001) | 1.0% vs. 1.3% | 11% vs. 23% (p < 0.001) | 158 vs. 158 (OTT) | TNK with better outcomes, no increased risk of sICH |

| Swedish Stroke Register (2024) [40] | Retrospective registry-based | 888/6560 MT: 15%/17.5% | 53% vs. 51% | 5% vs. 4.4% | 14% vs. 12% | 34 vs. 43 | TNK not non-inferior to rt-PA in safety; ↓ DNT (−9 min) |

| Murphy et al. (2023) [41] | Retrospective US cohort from 54 academic centers | 3432/55,894 MT: not reported | NA | 0.3% vs. 1.4% of major bleeding, requiring blood transfusion ICH: (3.5% vs. 3.0%) | 8.2% vs. 9.8% | NA | TNK with ↓ mortality, ICH and blood loss |

| Yao et al. (2024) [42] | Single-center retrospective observational cohort | 120/144 MT: 20%/23% | NIHSS improvement at 24 h: 64% vs. 50% (p = 0.024), length of hospitalization: 6 d vs. 8 d | 3.3% vs. 4.9% | NA | 36.5 vs. 50 | TNK with significant reduction in DNT (−13.5 min) and early NIHSS improvement |

| Zhao et al. (2024) [43] | Single-center retrospective observational cohort | 79/147 MT: 28%/33% | 58% vs. 51% (p = 0.37) | 2.5% vs. 6.1% (p = 0.38) | 14% vs. 10% | 43 vs. 43 | TNK with comparable safety and functional outcomes |

| Sekita et al. (2025) [26] | Single-center retrospective observational cohort | 138/138 MT: 78%/73% | 54% vs. 43% | 2% vs. 1% | 5% vs. 9% (in-hospital) | 27 vs. 34 | TNK with comparable outcomes at discharge and shorter DNT (−7 min) |

| Rousseau et al. (2025) [44] | Prospective data from Get With The Guidelines–Stroke registry | 9465/70,085 MT: 17.7%/13.8% | 45% vs. 46% (at discharge) | 3.1% vs. 3.1% | 5% vs. 4.6% (in-hospital) | LKW-IVT: 120 vs. 124 | TNK with similar safety and effectiveness outcomes to rt-PA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frol, S.; Zupan, M. Thrombus Composition and the Evolving Role of Tenecteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8675. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248675

Frol S, Zupan M. Thrombus Composition and the Evolving Role of Tenecteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8675. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248675

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrol, Senta, and Matija Zupan. 2025. "Thrombus Composition and the Evolving Role of Tenecteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8675. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248675

APA StyleFrol, S., & Zupan, M. (2025). Thrombus Composition and the Evolving Role of Tenecteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8675. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248675