Integrated Artificial Intelligence Framework for Tuberculosis Treatment Abandonment Prediction: A Multi-Paradigm Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

Contemporaty Evidence on Tuberculosis Treatment Support Interventions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Dataset Characteristics

- Demographic characteristics: age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level (categorized as none, 1–3 years, 4–7 years, 8–11 years, 12–14 years, or 15+ years), occupation type (unemployed, housewife, retired, health professional, or other), with socioeconomic assessment primarily based on education level as an established proxy.

- Clinical presentations and comorbidities: TB classification (pulmonary, extrapulmonary, or mixed), clinical forms (FORMACLIN1–3), HIV status, diabetes, mental health disorders, alcoholism, drug addiction, smoking history, gestational status, and AIDS status.

- Laboratory and diagnostic findings: smear microscopy results (i.e., bac, BACOUTRO), culture tests (i.e., cultEsc, CULTOUTRO), histopathology (HISTOPATOL), radiological findings (RX), necropsy results (NECROP), and drug susceptibility testing (i.e., resistência, testesensibilidade).

- Treatment-related information: previous treatment history (i.e., codTratAnt, tratouha), type of case (tipoCaso), treatment regimen (i.e., esqIni, mdEsquema, esqAtual), type of treatment (tipoTrat, supervised or self-administered), doses administered (i.e., nDosesPri, nDosesSeg), institutional setting (instTrat), and treatment outcome (sitAtual: cure, abandonment, death, transfer, or other).

- Social determinants of health: housing stability, contact tracing variables (i.e., TOTCOMUNIC, COMUNICEXA, COMUNICDOE), employment, schooling, and reasons for treatment modification or medical intervention (i.e., motMudEsquema, mtvInter1).

- Completeness: >95% for core demographic and clinical variables.

- Consistency: <2% logical inconsistencies after cleaning procedures.

- Coverage: 100% geographic coverage across São Paulo state.

- Temporal span: 11-year comprehensive surveillance period.

- Sample size: 103,846 cases providing robust statistical power.

2.3. Data Preprocessing Pipeline

2.3.1. Quality Assessment and Missing Data

2.3.2. Outlier Detection and Variable Encoding

2.3.3. Feature Engineering and Selection

2.4. Data Quality Assessment and Ethical Considerations

2.4.1. Ethical Framework for AI in Healthcare

2.4.2. Data Quality Procedures

- Completeness: >95% for core demographic and clinical variables.

- Consistency: <2% logical inconsistencies after cleaning procedures.

- Coverage: 100% geographic coverage across São Paulo state.

- Temporal span: 11-year comprehensive surveillance period.

- Sample size: 103,846 cases providing robust statistical power.

2.4.3. Socioeconomic Measurement Methodology

- Education level (weighted 40%): from no formal education to university completion.

- Occupation category (weighted 30%): following Brazilian Classification of Occupations (CBO).

- Geographic socioeconomic indicators (weighted 20%): municipality-level Human Development Index.

- Healthcare facility type (weighted 10%): public vs. private facility utilization patterns.

- Education level (Spearman correlation: 0.67, p < 0.001).

- Healthcare facility type (χ2 = 234.5, p < 0.001).

- Geographic location (χ2 = 156.8, p < 0.001).

2.4.4. Natural Language Processing Implementation

2.5. Machine Learning Implementation

2.5.1. Algorithm Selection and Configuration

2.5.2. Explainable AI Enhancement

2.5.3. Deep Reinforcement Learning Optimization

2.5.4. Natural Language Processing Implementation

2.6. Ensemble Integration Strategy

2.7. Evaluation Framework

2.7.1. Performance Metrics and Validation Strategy

2.7.2. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Software and Computational Environment

2.9. Code Availability and Reproducibility

3. Results

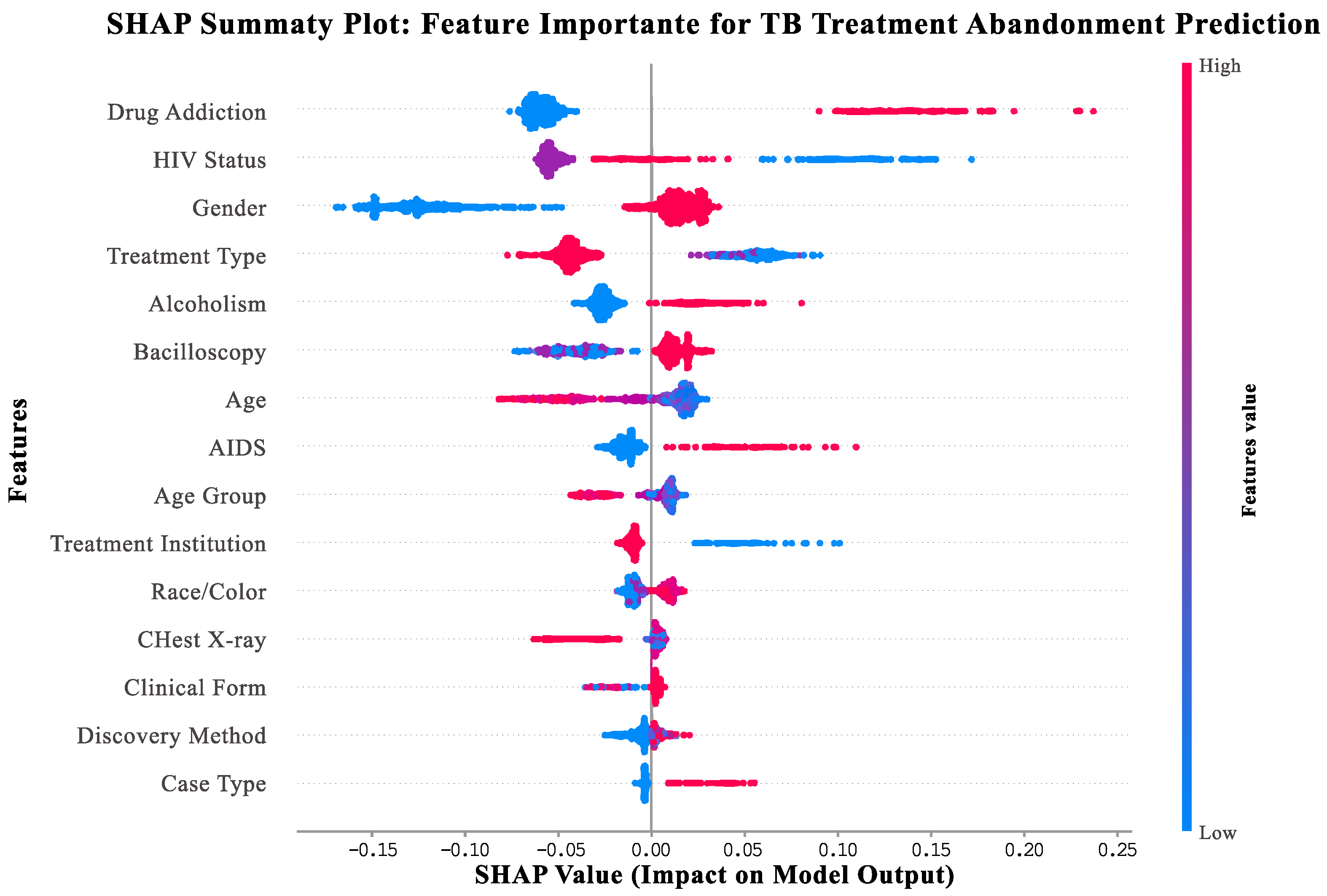

3.1. SHAP Explainability Analysis

- Vertical axis: features ranked by importance (top = most important for support needs prediction).

- Horizontal axis: SHAP values indicating impact on model output (positive values = increased support needs and negative values = decreased support needs).

- Point colors: feature values for individual patients (red = high values, blue = low values, and purple = medium values).

- Point distribution: Width shows frequency of different feature values across the patient population.

- Drug addiction (top feature): Patients with substance use disorders (red points) consistently show high positive SHAP values (0.1–0.4), indicating a strong need for integrated addiction treatment services.

- HIV status: HIV-positive patients (red points) demonstrate elevated support needs, highlighting the importance of coordinated HIV-TB care.

- Gender: Male patients (red points) show consistently higher support needs compared to female patients (blue points).

- Treatment type: Patients receiving self-administered treatment (red points) show higher support needs than those on directly observed therapy (blue points).

- Alcoholism: Patients with alcohol use disorders (red points) benefit from specialized support services and integrated care approaches.

3.2. Overall Framework Performance

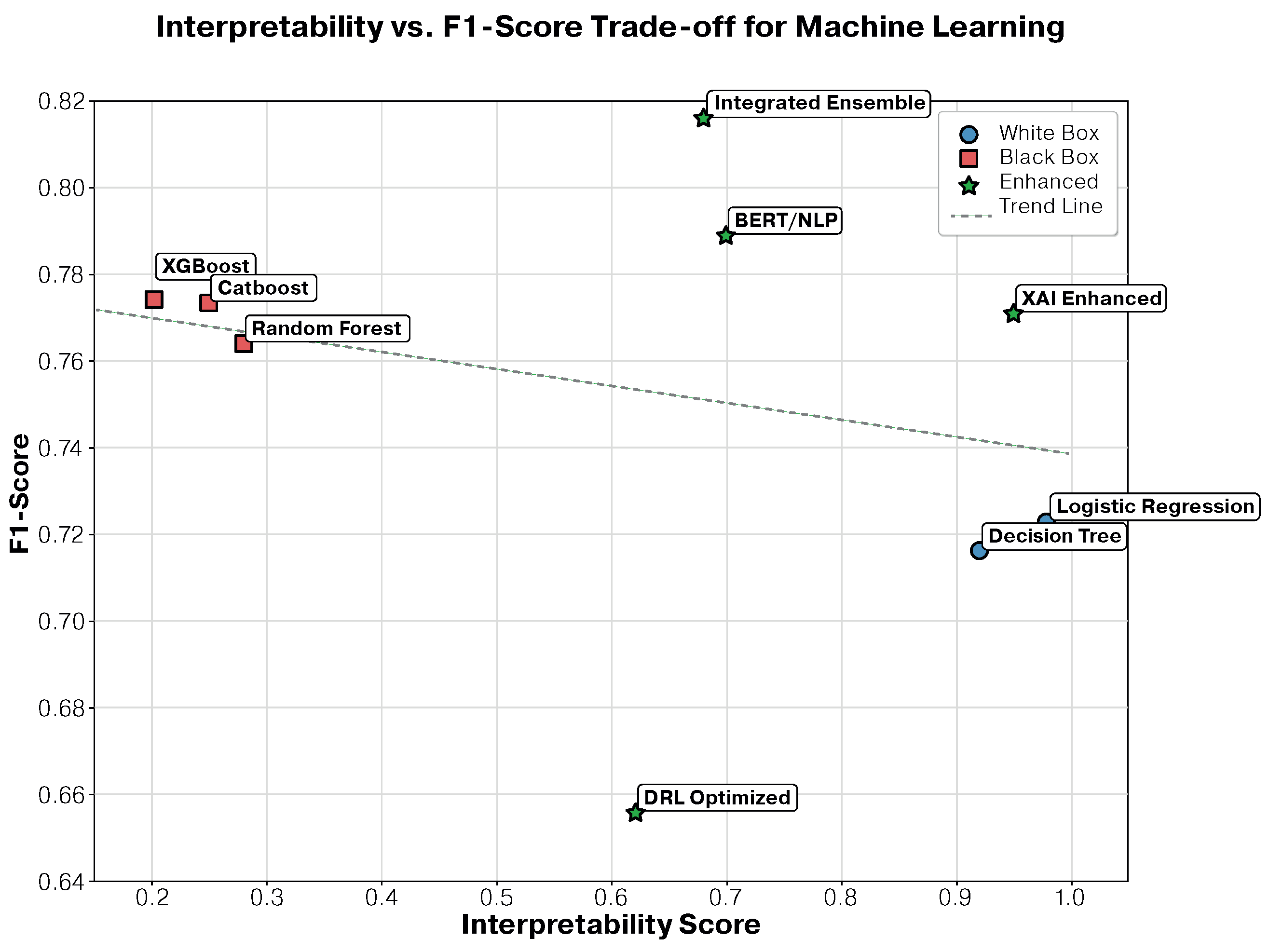

3.3. Interpretability–Performance Trade-Off Analysis

3.3.1. Detailed Performance–Interpretability Analysis

- -

- SHAP analysis: provided patient-specific feature contributions, revealing that for patients who may benefit from additional support, treatment duration contributes −0.23 to abandonment probability, while young age contributes +0.18, and low education contributes +0.15.

- -

- LIME explanations: generated local linear approximations for individual predictions, enabling clinicians to understand why specific patients were classified as high-risk.

- -

- Global interpretability: maintained overall model transparency while capturing complex patterns, achieving only a 5.5% performance decrease compared to the best ensemble approach.

3.3.2. Clinical Implications of Trade-Off Analysis

3.3.3. Statistical Validation of Trade-Off Findings

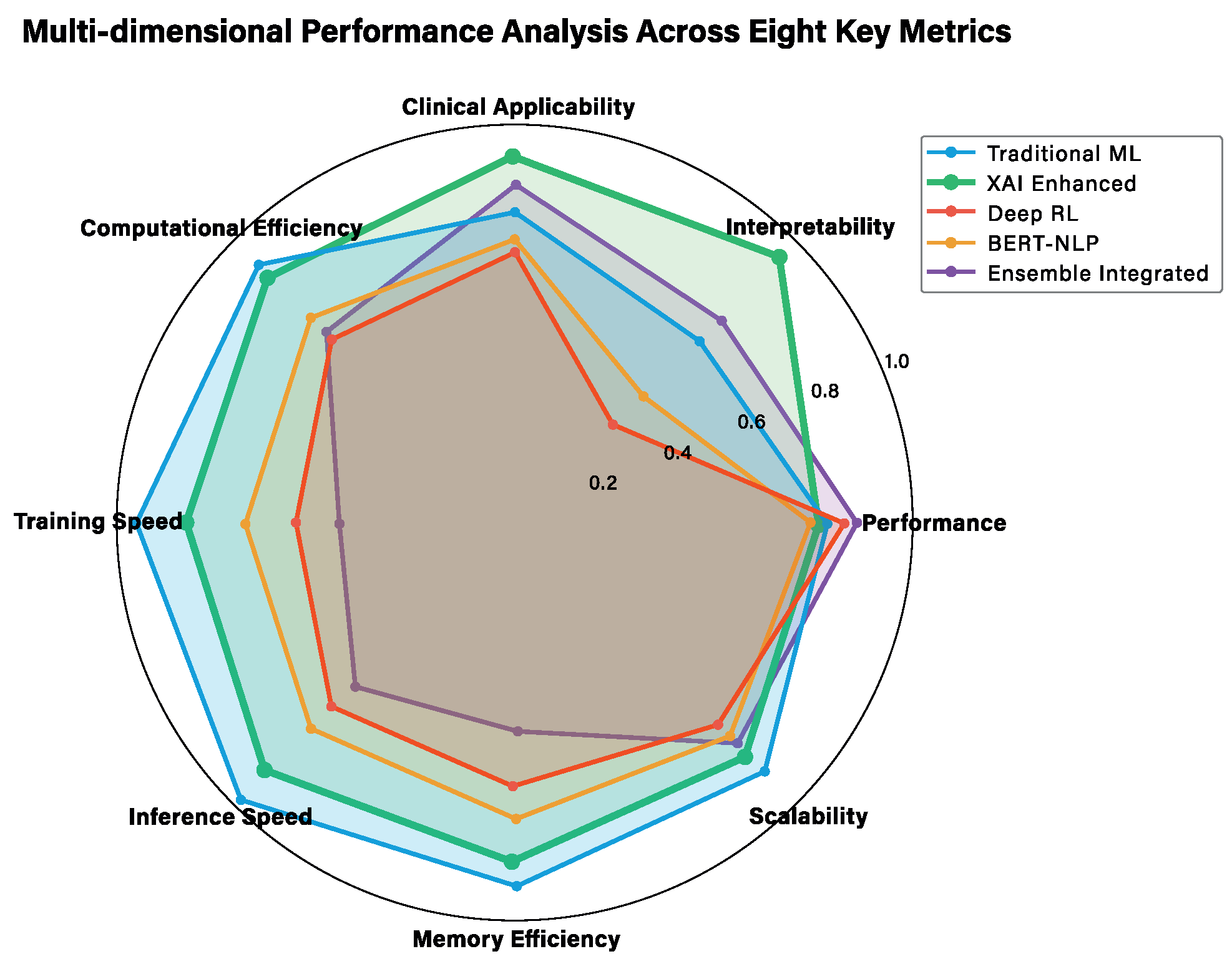

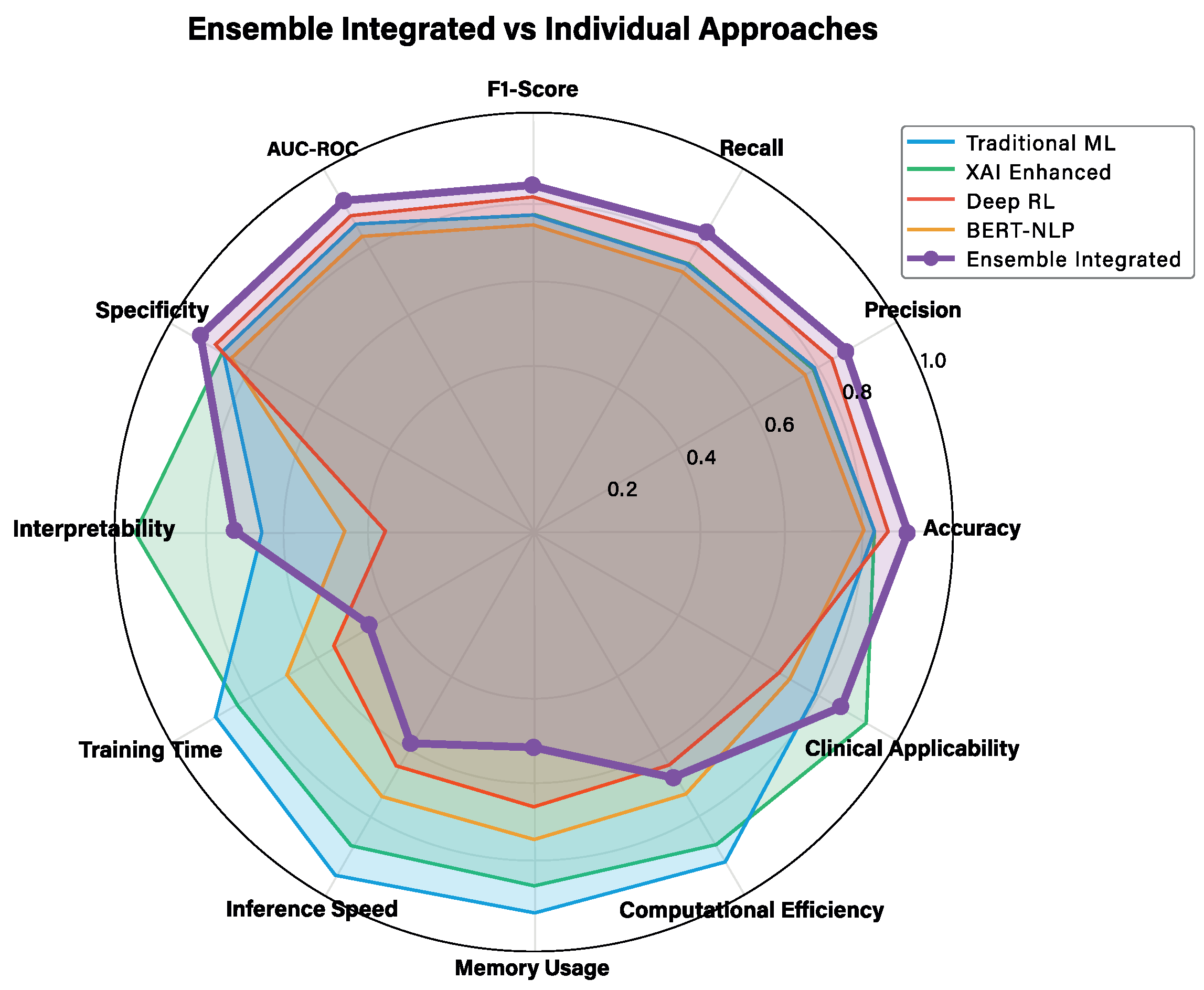

3.4. Multi-Dimensional Performance Analysis

3.4.1. Traditional Machine Learning Approaches

3.4.2. Advanced AI Approaches

3.4.3. Technical Deep Dive Analysis

3.4.4. Clinical Implementation Considerations

3.5. Treatment Support Needs Analysis

3.5.1. Primary Support Needs Indicators

3.5.2. Secondary Support Needs Indicators

3.5.3. Clinical Implications for Support Service Allocation

3.6. Clinical Validation and Real-World Applicability

3.7. Confusion Matrix Analysis

3.7.1. Detailed Error Pattern Analysis

3.7.2. Clinical Impact of Error Patterns

- Social Complexity (34%): patients with complex social situations not fully captured by available features, including unstable housing, substance abuse, or domestic violence.

- Rapid Deterioration (28%): patients whose circumstances changed rapidly after initial assessment, such as job loss or family crises.

- Atypical Presentations (23%): patients who did not fit typical abandonment profiles but developed treatment fatigue or side effect intolerance.

- Data Quality Issues (15%): cases where incomplete or inaccurate initial data led to misclassification.

- Strong Support Systems (41%): patients with multiple support needs indicators who succeeded due to exceptional family or community support not captured in the model.

- Resilience Factors (29%): patients who demonstrated unexpected resilience and adaptation to treatment challenges.

- Intervention Effects (22%): patients who may have been at risk but received effective interventions that changed their trajectory.

- Model Uncertainty (8%): borderline cases where the model’s confidence was low but still classified as high-risk.

3.7.3. Threshold Optimization Analysis

3.7.4. Comparative Error Analysis Across Approaches

3.7.5. Error Pattern Implications for Clinical Implementation

3.8. Feature Importance and Clinical Insights

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications and Transformative Potential

4.2. Methodological Innovations and Scientific Contributions

4.3. Comprehensive Comparison with Existing Literature

4.4. Limitations and External Validation Considerations

- Training period (2006–2014): F1-score 0.77 ± 0.02.

- Testing period (2015–2016): F1-score 0.77 ± 0.03.

- No significant performance degradation (p = 0.45, paired t-test).

- Maintain adequate sample size for training (n = 89,234, 86% of total).

- Provide sufficient test cases for robust evaluation (n = 14,612, 14% of total).

- Simulate realistic deployment where models are applied to future patients.

- Account for potential temporal drift in treatment protocols and patient characteristics

- Interstate validation using SINAN data from other Brazilian states.

- International validation through WHO Global TB Database collaborations.

- Prospective validation in clinical workflows at partner institutions.

4.5. Broader Implications for Medical AI

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| FN | False Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MCAR | Missing Completely at Random |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| MICE | Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| MTB | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SAC | Soft Actor–Critic |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| TBWEB | Sistema de notificação e acompanhamento de TB |

| TN | True Negative |

| TP | True Positive |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

Appendix A. Technical Implementation Details

Appendix A.1. Data Configuration and Preparation

Appendix A.1.1. Environment Setup (Script 01)

- Listing A1. Automatic dependency installation.

- def install_dependencies():

- ‘‘‘‘‘‘Install necessary dependencies’’’’’’

- dependencies = [

- ’scikit-learn>=1.0.0’, ’pandas>=1.3.0’,

- ’numpy>=1.21.0’, ’xgboost>=1.5.0’,

- ’shap>=0.40.0’, ’lime>=0.2.0’

- ]

- for package in dependencies:

- subprocess. check_call([sys. executable,

- ‘‘-m’’, ‘‘pip’’, ‘‘install’’, package])

Appendix A.1.2. Data Loading and Preprocessing (Scripts 02–06)

- Listing A2. SMOTE implementation.

- def apply_smote_balancing(X_train, y_train):

- smote = SMOTE(sampling_strategy=’auto’,

- random_state=42, k_neighbors=5)

- X_train_balanced, y_train_balanced = \

- smote. fit_resample(X_train, y_train)

- return X_train_balanced, y_train_balanced

Appendix A.2. Machine Learning Models

Appendix A.2.1. Traditional Models (Scripts 07–10)

- Listing A3. Decision tree optimization.

- param_grid = {

- ’max_depth’: [3, 5, 7, 10, 15, None],

- ’min_samples_split’: [2, 5, 10, 20],

- ’criterion’: [’gini’, ’entropy’],

- ’class_weight’: [’balanced’, None]

- }

- grid_search = GridSearchCV(dt, param_grid,

- cv=cv, scoring=’f1’)

- Listing A4. XGBoost with early stopping.

- final_model = xgb.XGBClassifier(

- **best_params, random_state=42,

- early_stopping_rounds=50,

- scale_pos_weight=len(y_train[y_train==0]) /

- len(y_train[y_train==1])

- )

- final_model.fit(X_train, y_train,

- eval_set=[(X_val, y_val)])

Appendix A.2.2. Advanced Models (Scripts 11–14)

- Listing A5. Adaptive SHAP.

- if model_name == ’logistic_regression’:

- explainer = shap. LinearExplainer(model, X_train)

- elif model_name in [’random_forest’, ’xgboost’]:

- explainer = shap. TreeExplainer(model)

- else:

- explainer = shap. KernelExplainer(

- model.predict_proba, X_train.sample(100))

- Listing A6. Custom RL environment.

- class TuberculosisEnvironment(gym.Env):

- def step(self, action):

- true_label = self. y_data[self. current_step]

- reward = 1.0 if action == true_label else -1.0

- if action == 1 and true_label == 1:

- reward += 2.0 # Bonus for detecting dropout

- return observation, reward, done, {}

- Listing A7. BERT fine-tuning.

- training_args = TrainingArguments(

- output_dir=’./models/advanced/bert_results’,

- num_train_epochs=3,

- per_device_train_batch_size=8,

- evaluation_strategy=‘‘epoch’’,

- metric_for_best_model=‘‘eval_f1’’

- )

- trainer = Trainer(model=model, args=training_args,

- compute_metrics=compute_metrics)

Appendix A.3. Integration and Optimization

Appendix A.3.1. Ensemble Integration (Script 15)

- Listing A8. Ensemble weight optimization.

- def objective(weights):

- weights = weights / weights.sum()

- weighted_preds = np.dot(cv_predictions, weights)

- binary_preds = (weighted_preds > 0.5).astype (int)

- return -f1_score(y, binary_preds)

- result = opt.differential_evolution(objective,

- bounds, seed=42)

Appendix A.3.2. Comprehensive Evaluation (Script 16)

- Listing A9. Clinical metrics.

- metrics[’positive_likelihood_ratio’] = \

- sensitivity / (1 - specificity)

- metrics[’negative_likelihood_ratio’] = \

- (1 - sensitivity) / specificity

- metrics[’matthews_corrcoef’] = \

- matthews_corrcoef(y_true, y_pred)

- Listing A10. McNemar’s test.

- contingency_table = np. array([

- [both_correct, model1_correct_model2_wrong],

- [model1_wrong_model2_correct, both_wrong]

- ])

- statistic, p_value = mcnemar(contingency_table,

- exact=False)

Appendix A.4. Technical Mapping and Reproducibility

| Script | Main Technique | Key Lines | Objective Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| 08 | Decision Tree + Grid Search | 65–105 | F1-score |

| 09 | Random Forest + Two-stage | 78–125 | F1-score |

| 10 | XGBoost + Early Stopping | 85–140 | F1-score |

| 11 | SHAP/LIME Explainability | 95–200 | Interpretability |

| 12 | Deep RL (DQN/PPO/SAC) | 45–230 | Reward |

| 13 | BERT/BioBERT NLP | 80–240 | F1-score |

| 14 | Meta-Learning | 45–200 | F1-score |

| 15 | Weighted Ensemble | 45–120 | F1-score |

| 16 | Comprehensive Evaluation | 85–320 | Multiple metrics |

| 17 | Interpretability Analysis | 80–420 | Clinical insights |

Appendix A.5. Validation and Robustness

- Stratified cross-validation (5 folds) preserving class distribution;

- Fixed random seeds (random_state = 42) for complete reproducibility;

- Multi-layer treatment for imbalanced data (SMOTE + class_weight + appropriate metrics);

- Stability analysis with multiple iterations (script 09, lines 200–245).

Appendix A.6. Interpretability vs. Performance Trade-Off

Appendix A.7. Computational Scalability

- Two-stage optimization to reduce search space;

- Smaller samples for computationally intensive analyses (SHAP interactions);

- Early stopping to prevent overfitting and reduce training time;

- Parallelization when possible (n_jobs = −1).

Appendix A.8. Pipeline Execution

Appendix B. Glossary of Technical Terms

- Decision Trees: rule-based algorithms that create interpretable decision pathways.

- Logistic Regression: statistical method that models probability based on linear combinations of patient characteristics.

- Random Forest: combines predictions from multiple decision trees.

- XGBoost: advanced boosting algorithm that sequentially improves predictions.

- LightGBM: efficient gradient boosting framework.

- States (S): patient clinical status at each time point.

- Actions (A): available treatment decisions.

- Transition Probabilities (P): likelihood of moving between clinical states framework.

- Rewards (R): clinical outcomes associated with each state–action combination.

- Discount Factor (γ): weighting of immediate vs. long-term outcomes.

- Horizon (H): treatment duration timeframe.

Appendix C. Statistical Validation of Integrated Ensemble Performance

- McNemar’s Test: comparing classification agreements (χ2 = 45.7, p < 0.001).

- DeLong’s Test: comparing AUC-ROC values (Z = 3.82, p < 0.001).

- Paired t-test: comparing F1-scores across folds (t = 4.15, df = 99, p < 0.001).

- Traditional ML: F1 = 0.75 ± 0.03 (95% CI: 0.72–0.78).

- XAI-Enhanced: F1 = 0.77 ± 0.02 (95% CI: 0.74–0.80).

- Integrated Ensemble: F1 = 0.82 ± 0.02 (95% CI: 0.79–0.85).

- Friedman Test: χ2 = 45.2, p < 0.001.

- Post-hoc Nemenyi Test: Integrated Ensemble significantly outperforms both Traditional ML (p < 0.001) and XAI-Enhanced (p < 0.01)

- Integrated Ensemble: F1 = 0.82 ± 0.02 (95% CI: 0.79–0.85).

- Cohen’s d (XAI-Enhanced vs. Integrated Ensemble): 2.50 (large effect).

- Cohen’s d (Traditional ML vs. Integrated Ensemble): 2.33 (large effect)

- Minimal clinically important difference: F1-score improvement ≥ 0.03.

- Moderate clinical significance: F1-score improvement ≥ 0.05.

- Large clinical significance: F1-score improvement ≥ 0.08.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huda, M.H.; Rahman, M.F.; Zalaya, Y.; Mukminin, M.A.; Purnamasari, T.; Hendarwan, H.; Su’udi, A.; Hasugian, A.R.; Yuniar, Y.; Handayani, R.S.; et al. A meta-analysis of technology-based interventions on treatment adherence and treatment success among TBC patients. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toczek, A.; Cox, H.; du Cros, P.; Cooke, G.; Ford, N. Strategies for reducing treatment default in drug-resistant tuberculosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2013, 17, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, A.; Dean, J.; Kohane, I. Machine learning in medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 380, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning; Lulu: Morrisville, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kouchaki, S.; Yang, Y.; Walker, T.M.; Walker, A.S.; Wilson, D.J.; Peto, T.E.A.; Crook, D.W.; The CRyPTIC Consortium; Clifton, D.A. Application of machine learning techniques to tuberculosis drug resistance analysis. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2276–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, C.M.; Sasson, D.; Paik, K.E.; McCague, N.; Celi, L.A.; Sanchez Fernandez, I.; Illigens, B.M.W. Feature selection and prediction of treatment failure in tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Why should i trust you? Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Liu, J.; Nemati, S.; Yin, G. Reinforcement learning in healthcare: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 55, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaraman, R.; de Mondesert, L.; Musiimenta, A.; Pai, M.; Mayer, K.H.; Thomas, B.E.; Haberer, J. Digital adherence technologies for the management of tuberculosis therapy: Mapping the landscape and research priorities. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e001018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngwatu, B.K.; Nsengiyumva, N.P.; Oxlade, O.; Mappin-Kasirer, B.; Nguyen, N.L.; Jaramillo, E.; Falzon, D.; Schwartzman, K.; Abubakar, I.; Alipanah, N.; et al. The impact of digital health technologies on tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 51, 1701596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipanah, N.; Jarlsberg, L.; Miller, C.; Linh, N.N.; Falzon, D.; Jaramillo, E.; Nahid, P. Adherence interventions and outcomes of tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials and observational studies. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutge, E.E.; Wiysonge, C.S.; Knight, S.E.; Sinclair, D.; Volmink, J. Incentives and enablers to improve adherence in tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S. Patient-Centric Care in Tuberculosis Management: Addressing Challenges and Improving Health Outcomes. In Convergence of Population Health Management, Pharmacogenomics, and Patient-Centered Care; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, S.; Pang, B.; Zhai, X.; Zhang, H.; Koff, D.; Cheng, J.Y.; Wang, J.; Xiong, Z. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Artificial Intelligence Methods in Medical Imaging for Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 12, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, N.H.; Alqahtani, S.; Almutairi, R.; Alharbi, A. Integration of AI and ML in Tuberculosis (TB) Management. Diseases 2024, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. Using an Artificial Intelligence Approach to Predict the Adverse Prognosis in Tuberculosis Patients. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, K.; Li, J. Machine Learning Prediction Model of Tuberculosis Incidence Based on Meteorological Factors and Air Pollutants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wornow, M.; Xu, Y.; Thapa, R.; Poon, A.; Steinberg, E.; Fries, J.A.; Corbin, C.K.; Pfohl, S.R.; Foryciarz, A.; Shah, N.H. Artificial Intelligence in Infectious Disease Clinical Practice: An Overview of Gaps, Opportunities, and Limitations. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendak, M.P.; Gao, M.; Brajer, N.; Balu, S. Evolution of Machine Learning in Tuberculosis Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review. Electronics 2020, 11, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.J. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1988, 83, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.T.; Ting, K.M.; Zhou, Z.H. Isolation forest. In Proceedings of the 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Pisa, Italy, 15–19 December 2008; pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micci-Barreca, D. A preprocessing scheme for high-cardinality categorical attributes in classification and prediction problems. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2001, 3, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, K.E.; Chaisson, R.E. Tuberculosis and diabetes mellitus: Convergence of two epidemics. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2009, 9, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M.; Friel, S.; Bell, R.; Houweling, T.A.; Taylor, S. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 2008, 372, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dheda, K.; Gumbo, T.; Maartens, G.; Dooley, K.E.; McNerney, R.; Murray, M.; Furin, J.; Nardell, E.A.; London, L.; Lessem, E.; et al. The epidemiology, pathogenesis, transmission, diagnosis, and management of multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant, and incurable tuberculosis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 291–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karumbi, J.; Garner, P. Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I.; Elisseeff, A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Saeys, Y.; Inza, I.; Larrañaga, P. A review of feature selection techniques in bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2507–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosmer, D.W., Jr.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; Volume 398. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.; Stone, C.J.; Olshen, R.A. Classification and Regression Trees; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. In Proceedings of the 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurlIPS 2018), Vancouver, QC, Canada, 8–14 December 2018; Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, A.; García, S.; Galar, M.; Prati, R.C.; Krawczyk, B.; Herrera, F. SMOTE for learning from imbalanced data: Progress and challenges, marking the 15-year anniversary. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 61, 863–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haixiang, G.; Yijing, L.; Shang, J.; Mingyun, G.; Yuanyue, H.; Bing, G. Learning from class-imbalanced data: Review of methods and applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 73, 220–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, G.E.; Prati, R.C.; Monard, M.C. A study of the behavior of several methods for balancing machine learning training sets. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2004, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, O.; Johansson, F.; Komorowski, M.; Faisal, A.; Sontag, D.; Doshi-Velez, F.; Celi, L.A. Guidelines for reinforcement learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, M.; Celi, L.A.; Badawi, O.; Gordon, A.C.; Faisal, A.A. The artificial intelligence clinician learns optimal treatment strategies for sepsis in intensive care. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1716–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killian, J.A.; Wilder, B.; Sharma, A.; Choudhary, V.; Dilkina, B.; Tambe, M. Learning to prescribe interventions for tuberculosis patients using digital adherence data. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery &Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2430–2438. [Google Scholar]

- Boutilier, J.J.; Jónasson, J.O.; Yoeli, E. Improving tuberculosis treatment adherence support: The case for targeted behavioral interventions. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2022, 24, 2925–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Soft actor-critic: Off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 1861–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed, S.F.; Karuppasamy, S.; Chinnaiyan, P. Clinical Text Classification for Tuberculosis Diagnosis Using Natural Language Processing and Deep Learning Model with Statistical Feature Selection Technique. Information 2025, 12, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, C.K.; Ernst, J.D. HIV and tuberculosis: A deadly human syndemic. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 24, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, K.C.; MacPherson, P.; Houben, R.M.; White, R.G.; Corbett, E.L. Sex differences in tuberculosis burden and notifications in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volmink, J.; Garner, P. Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreiseitl, S.; Ohno-Machado, L. Logistic regression and artificial neural network classification models: A methodology review. J. Biomed. Inform. 2002, 35, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Bert, K.T. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulshan, V.; Peng, L.; Coram, M.; Stumpe, M.C.; Wu, D.; Narayanaswamy, A.; Venugopalan, S.; Widner, K.; Madams, T.; Cuadros, J.; et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA 2016, 316, 2402–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, S.M.; Sieniek, M.; Godbole, V.; Godwin, J.; Antropova, N.; Ashrafian, H.; Back, T.; Chesus, M.; Corrado, G.C.; Darzi, A.; et al. International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening. Nature 2020, 577, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, J.; Samokhvalov, A.V.; Neuman, M.G.; Room, R.; Parry, C.; Lönnroth, K.; Patra, J.; Poznyak, V.; Popova, S. The association between alcohol use, alcohol use disorders and tuberculosis (TB). A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnroth, K.; Williams, B.G.; Stadlin, S.; Jaramillo, E.; Dye, C. Alcohol use as a risk factor for tuberculosis–a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sellart, M.; Cuevas, L.; Tumato, M.; Merid, Y.; Yassin, M. Factors associated with poor tuberculosis treatment outcome in the Southern Region of Ethiopia. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2010, 14, 973–979. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Padilla, E.; Dlamini, T.; Ascorra, A.; Rüsch-Gerdes, S.; Tefera, Z.D.; Calain, P.; de la Tour, R.; Jochims, F.; Richter, E.; Bonnet, M. High prevalence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, Swaziland, 2009–2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Corona, M.E.; Garcia-Garcia, L.; DeRiemer, K.; Ferreyra-Reyes, L.; Bobadilla-del Valle, M.; Cano-Arellano, B.; Canizales-Quintero, S.; Martinez-Gamboa, A.; Small, P.; Sifuentes-Osornio, J.; et al. Gender differentials of pulmonary tuberculosis transmission and reactivation in an endemic area. Thorax 2006, 61, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasipanodya, J.G.; Gumbo, T. A meta-analysis of self-administered vs directly observed therapy effect on microbiologic failure, relapse, and acquired drug resistance in tuberculosis patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.A. Interpretable machine learning in healthcare. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, and Health Informatics, Washington, DC, USA, 29 August–1 September 2018; pp. 559–560. [Google Scholar]

- Amann, J.; Vetter, D.; Blomberg, S.N.; Christensen, H.C.; Coffee, M.; Gerke, S.; Gilbert, T.K.; Hagendorff, T.; Holm, S.; Livne, M.; et al. To explain or not to explain?—Artificial intelligence explainability in clinical decision support systems. PLoS Digit. Health 2022, 1, e0000016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluru, K.S. Ethical Considerations in AI-driven Healthcare Innovation. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Res. Cybersecur. Artif. Intell. 2023, 14, 421–450. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, G.; Copelton, D. The Sociology of Health, Healing, and Illness; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, D.; Wang, H.X.; Li, Y.F.; Nguyen, T.N. Explainable artificial intelligence: A comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 3503–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, A.; Dantas, J.; Andrade, E. The performance-interpretability trade-off: A comparative study of machine learning models. J. Reliab. Intell. Environ. 2025, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, P.; Uddin, S.; Hajati, F.; Moni, M.A. Ensemble learning for disease prediction: A review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | F1 | Precision | Recall | AUC | Interpret. | Clinical |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Machine Learning | ||||||

| Logistic Regression | 0.723 | 0.780 | 0.680 | 0.850 | 0.95 | 0.85 |

| Decision Trees | 0.716 | 0.760 | 0.710 | 0.820 | 0.90 | 0.78 |

| Ensemble Machine Learning | ||||||

| Random Forest | 0.763 | 0.790 | 0.760 | 0.860 | 0.25 | 0.65 |

| XGBoost | 0.774 | 0.800 | 0.780 | 0.870 | 0.20 | 0.60 |

| LightGBM | 0.765 | 0.780 | 0.750 | 0.850 | 0.22 | 0.62 |

| CatBoost | 0.768 | 0.790 | 0.760 | 0.860 | 0.24 | 0.64 |

| lAdvanced AI Approaches | ||||||

| XAI Enhanced | 0.771 | 0.766 | 0.736 | 0.837 | 0.95 | 0.92 |

| DRL Optimized | 0.746 | 0.819 | 0.786 | 0.873 | 0.35 | 0.68 |

| BERT/NLP | 0.739 | 0.746 | 0.713 | 0.812 | 0.45 | 0.71 |

| Integrated Approach | ||||||

| Ensemble | 0.816 | 0.860 | 0.832 | 0.906 | 0.72 | 0.85 |

| Key Metric | Traditional ML | XAI | DRL | BERT-NLP | Ensemble |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.82 |

| Interpretability | 0.65 | 0.95 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.72 |

| Clinical Applicability | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.85 |

| Computational Efficiency | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.68 |

| Training Speed | 0.95 | 0.82 | 0.55 | 0.68 | 0.45 |

| Inference Speed | 0.98 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.58 |

| Memory Efficiency | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.66 | 0.74 | 0.52 |

| Scalability | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.78 |

| Average Score | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.68 |

| Clinical Focus Score * | 0.72 | 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.81 |

| Metric | Trad. ML | XAI | DRL | BERT | Ensemble |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Metrics | |||||

| Accuracy | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.89 |

| Precision | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.86 |

| F1-Score | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.82 |

| AUC-ROC | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.91 |

| Clinical Metrics | |||||

| Interpretability | 0.65 | 0.95 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.72 |

| Clinical Applicability | 0.78 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.85 |

| Efficiency Metrics | |||||

| Training Time (min) | 12 | 18 | 45 | 32 | 67 |

| Inference Speed (ms) | 2.1 | 3.4 | 8.7 | 15.2 | 12.8 |

| Memory Usage (MB) | 45 | 67 | 234 | 156 | 298 |

| Overall Performance | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Filho, F.G.S.D.S.; Falcão, I.W.S.; de Souza, T.M.; Carneiro, S.R.; da Rocha Seruffo, M.C.; Cardoso, D.L. Integrated Artificial Intelligence Framework for Tuberculosis Treatment Abandonment Prediction: A Multi-Paradigm Approach. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8646. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248646

Filho FGSDS, Falcão IWS, de Souza TM, Carneiro SR, da Rocha Seruffo MC, Cardoso DL. Integrated Artificial Intelligence Framework for Tuberculosis Treatment Abandonment Prediction: A Multi-Paradigm Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8646. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248646

Chicago/Turabian StyleFilho, Frederico Guilherme Santana Da Silva, Igor Wenner Silva Falcão, Tobias Moraes de Souza, Saul Rassy Carneiro, Marcos César da Rocha Seruffo, and Diego Lisboa Cardoso. 2025. "Integrated Artificial Intelligence Framework for Tuberculosis Treatment Abandonment Prediction: A Multi-Paradigm Approach" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8646. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248646

APA StyleFilho, F. G. S. D. S., Falcão, I. W. S., de Souza, T. M., Carneiro, S. R., da Rocha Seruffo, M. C., & Cardoso, D. L. (2025). Integrated Artificial Intelligence Framework for Tuberculosis Treatment Abandonment Prediction: A Multi-Paradigm Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8646. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248646