Long-Term Outcomes of the Aorfix™ Stent Graft in Japanese Patients with Severely Angulated Aortic Necks: A Single-Center Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Follow-Up Protocol

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

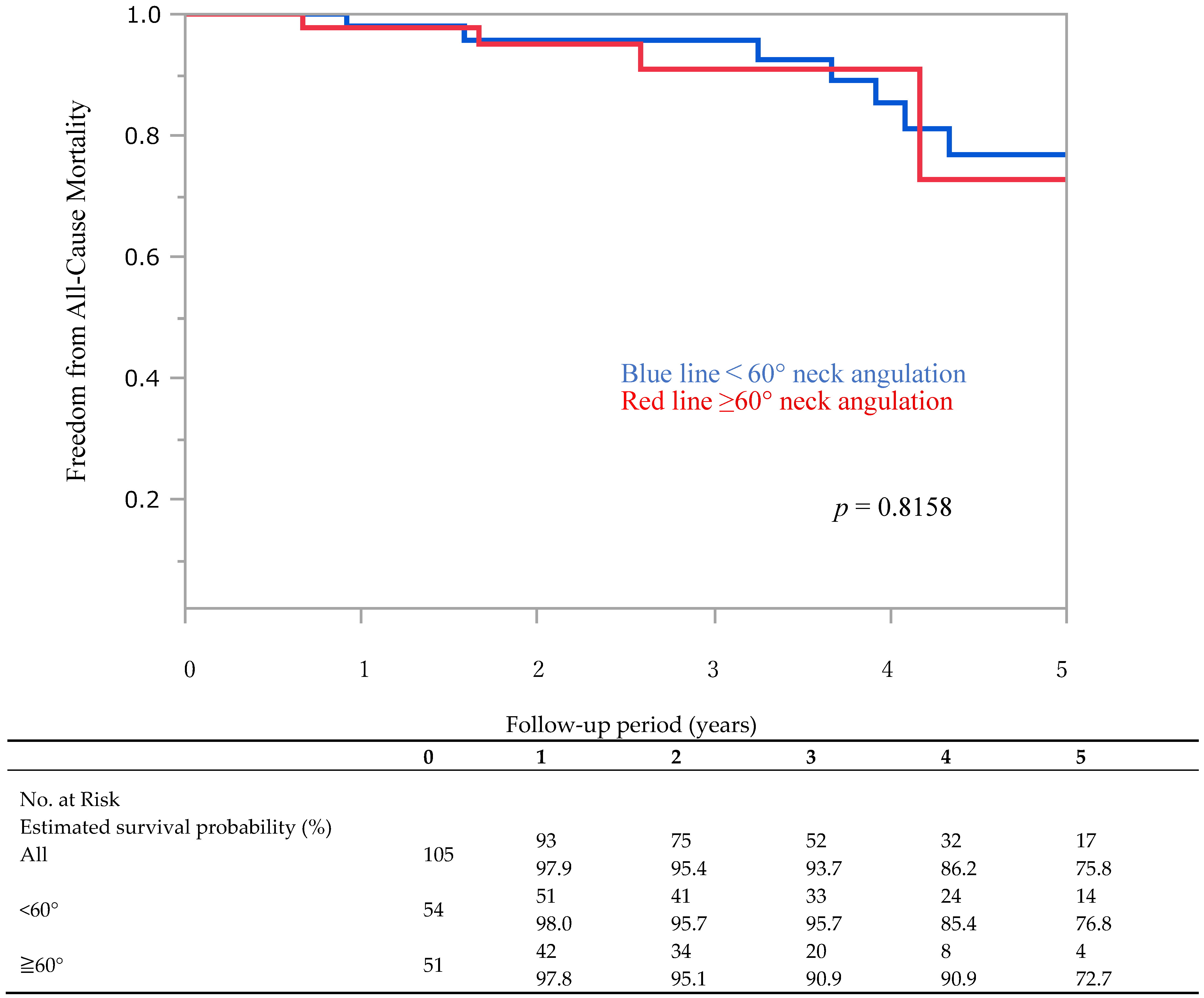

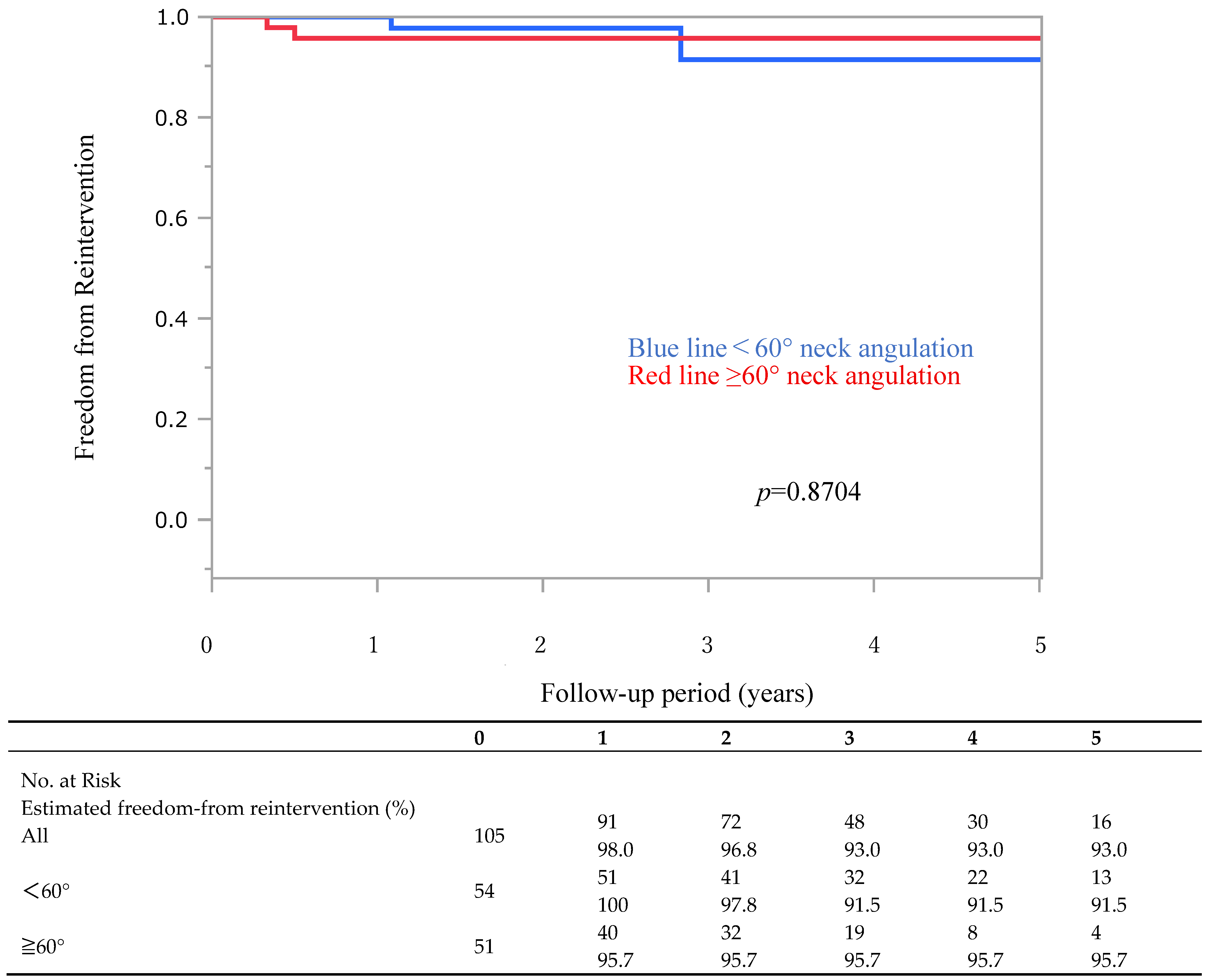

3. Results

3.1. Overview

3.2. Primary Technical Success and Early Complications

3.3. Late Complications and Endoleaks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAA | abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| ARBITER-II | Aorfix Bifurcated Safety and Performance Trial: phase II, angulated vessels |

| IAA | iliac artery aneurysm |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| EIA | external iliac artery |

| EVAR | endovascular aneurysm repair |

| IFU | instructions for use |

| IIA | internal iliac artery |

| PYTHAGORAS | Prospective Aneurysm Trial: High Angle Aorfix Bifurcated Stent Graft |

| SMA | superior mesenteric artery |

References

- United Kingdom EVAR Trial Investigators; Greenhalgh, R.M.; Brown, L.C.; Powell, J.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Epstein, D.; Sculpher, M.J. Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederle, F.A.; Freischlag, J.A.; Kyriakides, T.C.; Padberg, F.T., Jr.; Matsumura, J.S.; Kohler, T.R.; Lin, P.H.; Jean-Claude, J.M.; Cikrit, D.F.; Swanson, K.M.; et al. Outcomes following endovascular vs open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: A randomized trial. JAMA 2009, 302, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.T.; Sweeting, M.J.; Ulug, P.; Blankensteijn, J.D.; Lederle, F.A.; Becquemin, J.P.; Greenhalgh, R.M.; Greenhalgh, R.M.; Beard, J.D.; Buxton, M.J.; et al. Meta-analysis of individual-patient data from EVAR-1, DREAM, OVER and ACE trials comparing outcomes of endovascular or open repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm over 5 years. Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternbergh, W.C., 3rd; Carter, G.; York, J.W.; York, J.W.; Yoselevitz, M.; Money, S.R. Aortic neck angulation predicts adverse outcome with endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2002, 35, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, I.P.; Turley, L.P.; Mwipatayi, D.L.; Thomas, A.; Mwipatayi, M.T.; Mwipatayi, B.P. The Impact of endograft selection on outcomes following treatment outside of instructions for use (IFU) in endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR). Cureus 2021, 13, e14841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schaik, T.G.; Yeung, K.K.; Verhagen, H.J.; de Bruin, J.L.; van Sambeek, M.; Balm, R.; Zeebregts, C.J.; van Herwaarden, J.A.; Blankensteijn, J.D.; Grobbee, D.E.; et al. Long-term survival and secondary procedures after open or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 66, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weale, A.R.; Balasubramaniam, K.; Macierewicz, J.; Hardman, J.; Horrocks, M. Outcome and safety of Aorfix stent graft in highly angulated necks- a prospective observational study (ARBITER 2). Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2011, 41, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malas, M.B.; Jordan, W.D.; Cooper, M.A.; Qazi, U.; Beck, A.W.; Belkin, M.; Robinson, W.; Fillinger, M. Performance of the Aorfix endograft in severely angulated proximal necks in the PYTHAGORAS United States clinical trial. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 62, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malas, M.B.; Hicks, C.W.; Jordan, W.D., Jr.; Hodgson, K.J.; Mills, J.L.; Makaroun, M.S., Sr.; Belkin, M.; Fillinger, M.F.; PYTHAGORAS Investigators. Five-year outcomes of the PYTHAGORAS U.S. clinical trial of the Aorfix endograft for endovascular aneurysm repair in patients with highly angulated aortic necks. J. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 65, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, J.L.; Baas, A.F.; Buth, J.; Prinssen, M.; Verhoeven, E.L.; Cuypers, P.W.; van Sambeek, M.R.; Balm, R.; Grobbee, D.E.; Blankensteijn, J.D.; et al. Long-term outcome of open or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stather, P.W.; Wild, J.B.; Sayers, R.D.; Bown, M.J.; Choke, E. Endovascular aortic aneurysm repair in patients with hostile neck anatomy. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2013, 20, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, M.P.; Fillinger, M.F.; Morrison, T.M.; Abel, D. The influence of gender and aortic aneurysm size on eligibility for endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 54, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshina, K.; Ishimaru, S.; Sasabuchi, Y.; Yasunaga, H.; Komori, K.; Japan Committee for Stentgraft Management. Outcomes of endovascular repair for abdominal aortic aneurysms: A nationwide survey in Japan. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburahma, A.F.; Campbell, J.E.; Mousa, A.Y.; Hass, S.M.; Stone, P.A.; Jain, A.; Nanjundappa, A.; Dean, L.S.; Keiffer, T.; Habib, J. Clinical outcomes for hostile versus favorable aortic neck anatomy in endovascular aortic aneurysm repair using modular devices. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 54, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EVAR trial participants. Endovascular aneurysm repair versus open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1): Randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2005, 365, 2179–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertini, J.N.; Perdikides, T.; Soong, C.V.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Trojanowska, M.; Yusuf, S.W. Endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients with severe angulation of the proximal neck using a flexible stent-graft: European Multicenter Experience. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2006, 47, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hingorani, A.P.; Ascher, E.; Marks, N.; Shiferson, A.; Patel, N.; Gopal, K.; Jacob, T. Iatrogenic injuries of the common femoral artery (CFA) and external iliac artery (EIA) during endograft placement: An underdiagnosed entity. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 50, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchliffe, R.J.; Macierewicz, J.; Hopkinson, B.R. Early results of a flexible bifurcated endovascular stent-graft (Aorfix). J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2004, 45, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Masuda, E.M.; Caps, M.T.; Singh, N.; Yorita, K.; Schneider, P.A.; Sato, D.T.; Eklof, B.; Nelken, N.A.; Kistner, R.L. Effect of ethnicity on access and device complications during endovascular aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2004, 40, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoga, N.K.; Fujimura, N.; Hayashi, K.; Obara, H.; Shimizu, H.; Lee, J.T. Outcomes of Endovascular Repair of Aortoiliac Aneurysm and Analyses of Anatomic Suitability for Internal Iliac Artery Preserving Devices in Japanese Patients. Circ. J. 2017, 81, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašiová, M.; Koščo, M.; Pavlíková, V.; Hudák, M.; Moščovič, M.; Kočan, L. Predictors of overall mortality after endovascular abdominal aortic repair-A single center study. Vascular 2025, 33, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahia, S.S.; Holt, P.J.; Jackson, D.; Patterson, B.O.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Thompson, M.M.; Karthikesalingam, A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term survival after elective infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm repair 1969–2011: 5 year survival remains poor despite advances in medical care and treatment strategies. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2015, 50, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, M.E.; Morasch, M.D.; Park, T.; Flannery, W.D.; Makaroun, M.S.; Cho, J.S. Long-term sac behavior after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair with the Excluder low permeability endoprosthesis. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 53, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, P.J.; Karthikesalingam, A.; Patterson, B.O.; Ghatwary, T.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Loftus, I.M.; Thompson, M.M. Aortic rupture and sac expansion after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br. J. Surg. 2012, 99, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakoshi, S.; Ichihashi, S.; Higashiura, W.; Itoh, H.; Sakaguchi, S.; Tabayashi, N.; Uchida, H.; Kichikawa, K. A decade of outcomes and predictors of sac enlargement after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair using Zenith endografts in a Japanese population. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2014, 25, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demanget, N.; Avril, S.; Badel, P.; Orgéas, L.; Geindreau, C.; Albertini, J.N.; Favre, J.P. Computational comparison of the bending behavior of aortic stent-grafts. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 5, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertini, J.N.; DeMasi, M.A.; Macierewicz, J.; El Idrissi, R.; Hopkinson, B.R.; Clément, C.; Branchereau, A. Aorfix stent graft for abdominal aortic aneurysms reduces the risk of proximal type 1 endoleak in angulated necks: Bench-test study. Vascular 2005, 13, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimura, N.; Obara, H.; Matsubara, K.; Watada, S.; Shibutani, S.; Akiyoshi, T.; Harada, H.; Kitagawa, Y. Characteristics and risk factors for type 2 endoleak in an East Asian population from a Japanese multicenter database. Circ. J. 2016, 80, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmieder, G.C.; Stout, C.L.; Stokes, G.K.; Parent, F.N.; Panneton, J.M. Endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair: Duplex ultrasound imaging is better than computed tomography at determining the need for intervention. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 50, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraha, I.; Luchetta, M.L.; De Florio, R.; Cozzolino, F.; Casazza, G.; Duca, P.; Parente, B.; Orso, M.; Germani, A.; Eusebi, P.; et al. Ultrasonography for endoleak detection after endoluminal abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD010296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikesalingam, A.; Al-Jundi, W.; Jackson, D.; Boyle, J.R.; Beard, J.D.; Holt, P.J.; Thompson, M.M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of duplex ultrasonography, contrast-enhanced ultrasonography or computed tomography for surveillance after endovascular aneurysm repair. Br. J. Surg. 2012, 99, 1514–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aorfix (N = 105) | <60° (n = 54) | ≥60° (n = 51) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 75.5 ± 8.1 | 73.9 ± 8.4 | 77.1 ± 7.6 | 0.0497 |

| Female sex, no. (%) | 15 (14.3) | 4 (7.4) | 11 (21.6) | 0.0354 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.4 ± 3.8 | 24.2 ± 4.0 | 22.7 ± 3.6 | 0.0455 |

| Obesity, no. (%) | 32 (30.5) | 20 (37.0) | 12 (23.5) | 0.0029 |

| Coronary artery disease, no. (%) | 36 (34.3) | 21 (38.9) | 15 (29.4) | 0.3056 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, no. (%) | 28 (26.7) | 14 (25.9) | 14 (27.5) | 0.8598 |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 85 (81.0) | 42 (77.8) | 43 (84.3) | 0.3924 |

| Lower extremity artery disease, no. (%) | 4 (3.8) | 2 (3.7) | 2 (3.9) | 0.9535 |

| Cancer, no. (%) | 27 (25.7) | 12 (22.2) | 15 (29.4) | 0.3993 |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 26 (24.8) | 18 (33.3) | 8 (15.7) | 0.0342 |

| Pulmonary disease, no. (%) | 28 (26.7) | 15 (27.8) | 13 (25.5) | 0.7910 |

| Tobacco use, no. (%) | 79 (75.2) | 42 (77.8) | 37 (72.6) | 0.5350 |

| Renal disease, no. (%) | 17 (16.2) | 10 (18.5) | 7 (13.7) | 0.5040 |

| Dyslipidemia, no. (%) | 71 (67.6) | 35 (64.8) | 36 (70.6) | 0.5271 |

| Hostile abdomen, no. (%) | 30 (28.6) | 12 (22.2) | 18 (35.3) | 0.1376 |

| ASA class III, no. (%) | 55 (52.4) | 30 (55.6) | 25 (49.0) | 0.5026 |

| Antiplatelet agents, no. (%) | 34 (32.4) | 19 (35.2) | 15 (29.4) | 0.5271 |

| Anticoagulated, no. (%) | 10 (9.5) | 3 (5.6) | 7 (13.7) | 0.1496 |

| Aorfix (N = 105) | <60° (n = 54) | ≥60° (n = 51) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sac diameter, mm | 51.6 ± 7.1 | 50.3 ± 5.6 | 53.0 ± 8.2 | 0.0560 |

| Proximal neck diameter, mm | 20.2 ± 2.7 | 20.7 ± 2.5 | 19.6 ± 2.9 | 0.0521 |

| Proximal neck length, mm | 34.5 ± 15.1 | 33.3 ± 13.9 | 35.9 ± 16.4 | 0.3771 |

| Patients with neck length <15 mm | 4 (3.8) | 3 (5.6) | 1 (2.0) | 0.3245 |

| Proximal neck angle, ° | 54.8 ± 29.2 | 30.7 ± 15.1 | 80.3 ± 15.6 | <0.0001 |

| Patients with neck angle, ≥90° | 15 (14.3) | - | 15 (29.4) | <0.0001 |

| Aorfix (N = 105) | <60° (n = 54) | ≥60° (n = 51) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary technical success, no. (%) | 103 (100) | 50 (100) | 54 (100) | |

| Procedure duration, mean ± SD, min | 154.1 ± 51.0 | 140.1 ± 47.4 | 168.9 ± 50.9 | 0.0034 |

| Bleeding, mean ± SD, ml | 132.1 ± 168.4 | 146.0 ± 205.6 | 117.5 ± 117.2 | 0.3875 |

| Contrast volume, mean ± SD, ml | 177.9 ± 50.5 | 167.7 ± 47.2 | 189.5 ± 52.0 | 0.0301 |

| Fluoroscopy time, mean ± SD, min | 46.7 ± 22.1 | 38.0 ± 17.2 | 56.1 ± 23.0 | <0.0001 |

| IMA occlusion, no. (%) | 54 (51.4) | 31 (57.4) | 23 (45.1) | 0.2066 |

| IMA embolization | 20 (19.0) | 11 (20.4) | 9 (17.7) | 0.7222 |

| Aortic cuff first | 35 (33.3) | 20 (37.0) | 15 (29.4) | 0.4068 |

| IIA embolization, no. (%) Unilateral Bilateral | 48 (45.7) 41 (39.0) 7 (6.7) | 25 (46.3) 21 (38.9) 4 (7.4) | 23 (45.1) 20 (39.2) 3 (5.9) | 0.9514 |

| IIA revasculization, no. (%) | 17 (16.2) | 5 (9.3) | 12 (23.5) | 0.0449 |

| Necessary adjunctive procedures, no. (%) | ||||

| Access site PTA | 17 (16.2) | 6 (11.1) | 11 (21.6) | 0.1440 |

| Renal angioplasty | 7 (6.7) | 5 (9.3) | 2 (3.9) | 0.2650 |

| Proximal extension cuff | 8 (7.6) | 2 (3.7) | 6 (11.8) | 0.1129 |

| Aorfix (N = 105) | <60° (n = 54) | ≥60° (n = 51) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day freedom from SVS MAE, % | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0.2278 |

| 30-day Type 1 EL, no. (%) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0.2278 |

| 30-day Type 2 EL, no. (%) | 25 (23.8) | 12 (22.2) | 13 (25.5) | 0.4367 |

| 30-day endograft migration, no. (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Total (N = 105) | <60° (n = 54) | ≥60° (n = 51) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | |

| Sac shrinkage (≥5 mm), %(n) | 57.8% (52/90) | 57.4% (31/54) | 68.7% (11/16) | 54.0% (27/50) | 62.5% (20/32) | 76.9% (10/13) | 62.5% (25/40) | 50.0% (11/22) | 33.3% (1/3) |

| Sac expansion (≥5 mm), %(n) | 0% (0/90) | 5.6% (3/54) | 6.3% (1/16) | 0% (0/50) | 3.1% (1/32) | 7.7% (1/13) | 0% (0/40) | 9.1% (2/22) | 0% (0/3) |

| p-value | 0.4164 | 0.5147 | 0.2024 | ||||||

| Total (N = 105) | <60° (n = 54) | ≥60° (n = 51) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | |

| Type 1 or 3 EL, %(n) | 0 (0/89) | 0 (0/53) | 0 (0/17) | 0 (0/49) | 0 (0/31) | 0 (0/14) | 0 (0/40) | 0 (0/22) | 0 (0/3) |

| Type 2 EL, %(n) | 26.7% (24/90) | 22.2% (12/54) | 18.8% (3/16) | 26.5% (13/49) | 21.9% (7/32) | 15.4% (2/13) | 26.8% (11/41) | 22.7% (5/22) | 33.3% (1/3) |

| p-value | 0.9745 | 0.9410 | 0.4972 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shimizu, R.; Sumi, M.; Murakami, Y.; Hara, M.; Ohki, T. Long-Term Outcomes of the Aorfix™ Stent Graft in Japanese Patients with Severely Angulated Aortic Necks: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8617. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248617

Shimizu R, Sumi M, Murakami Y, Hara M, Ohki T. Long-Term Outcomes of the Aorfix™ Stent Graft in Japanese Patients with Severely Angulated Aortic Necks: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8617. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248617

Chicago/Turabian StyleShimizu, Riha, Makoto Sumi, Yuri Murakami, Masayuki Hara, and Takao Ohki. 2025. "Long-Term Outcomes of the Aorfix™ Stent Graft in Japanese Patients with Severely Angulated Aortic Necks: A Single-Center Retrospective Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8617. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248617

APA StyleShimizu, R., Sumi, M., Murakami, Y., Hara, M., & Ohki, T. (2025). Long-Term Outcomes of the Aorfix™ Stent Graft in Japanese Patients with Severely Angulated Aortic Necks: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8617. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248617