Real-World Clinical Outcomes and Biopsy Patterns of Older Patients with Unresected Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Primary Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Design

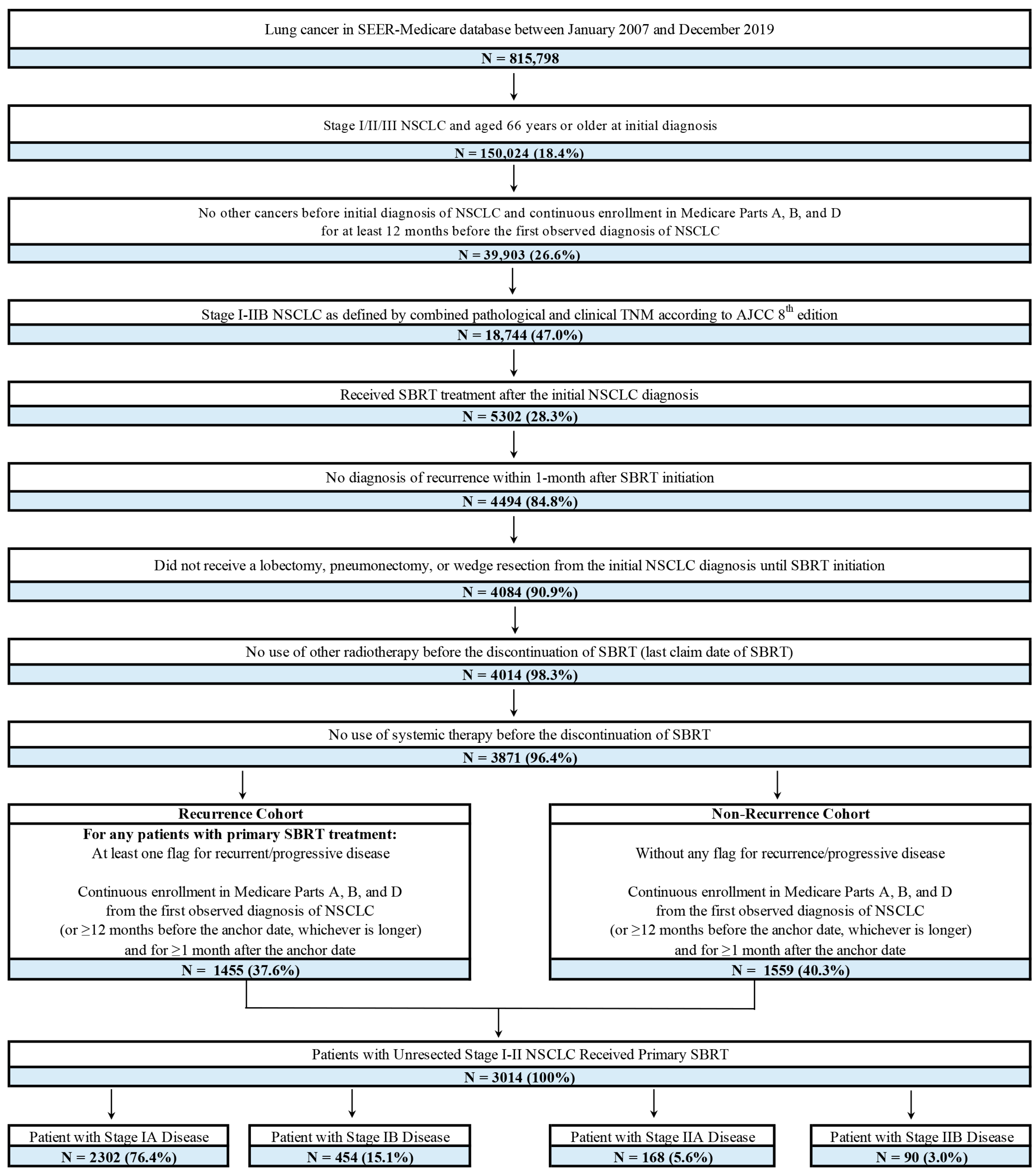

2.2. Patient Selection

2.3. Outcomes and Measures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Survival Outcomes

3.2.1. Real-World Event-Free Survival

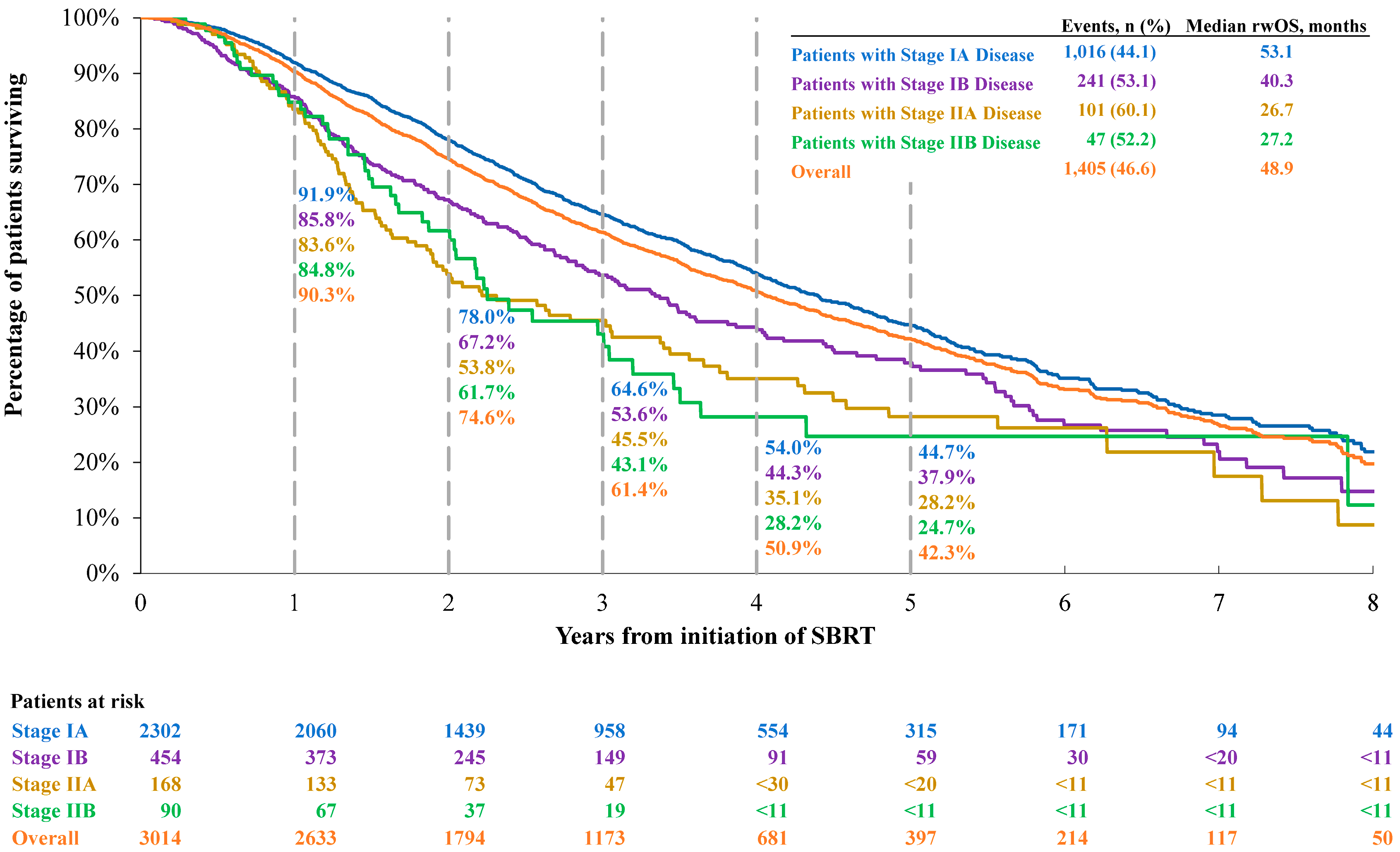

3.2.2. Overall Survival

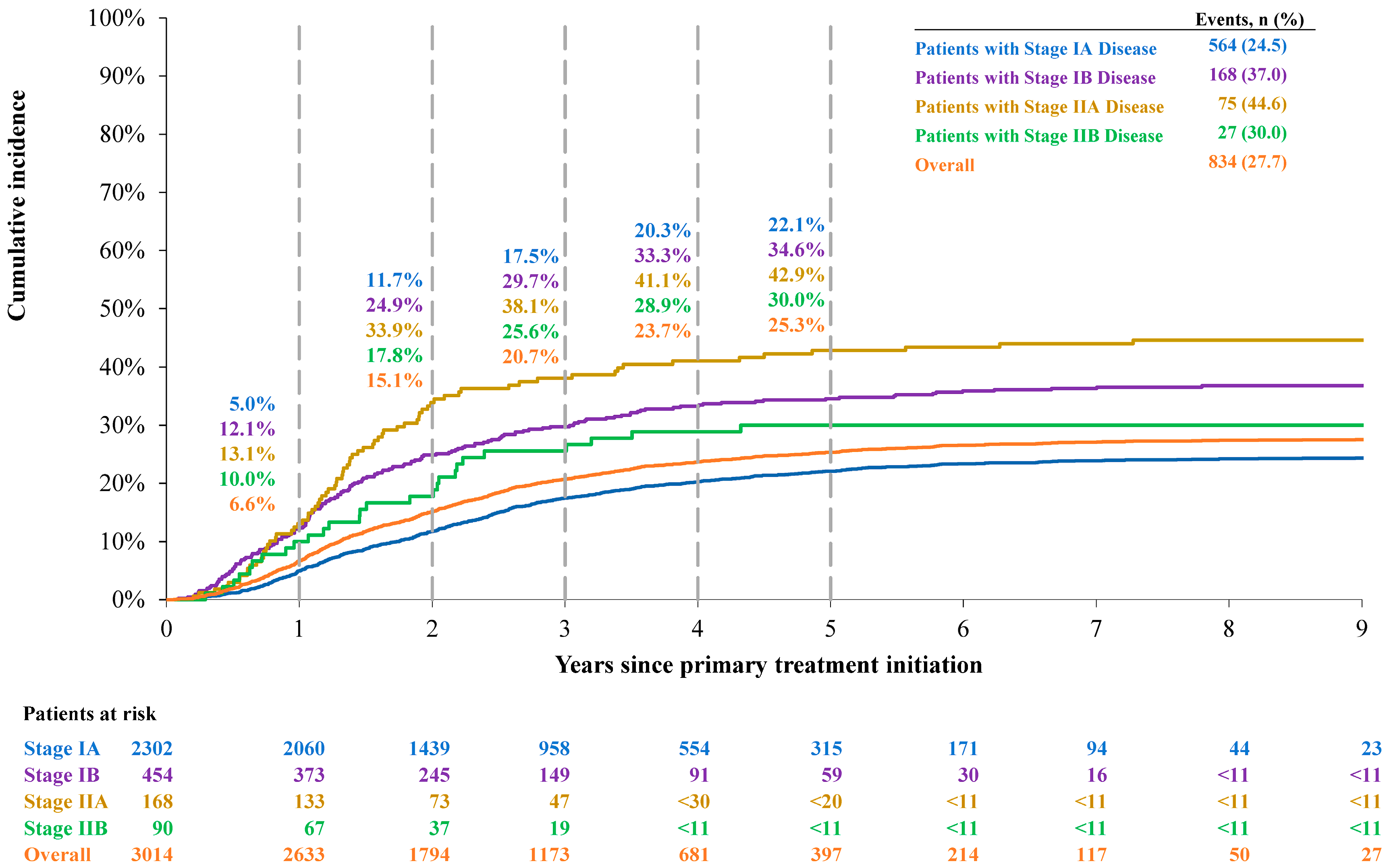

3.2.3. Cumulative Incidence of Lung Cancer-Specific Death

3.2.4. TDDM

3.3. Lung Biopsy Patterns

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leiter, A.; Veluswamy, R.R.; Wisnivesky, J.P. The global burden of lung cancer: Current status and future trends. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 624–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/2024-cancer-facts-figures.html (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Molina, J.R.; Yang, P.; Cassivi, S.D.; Schild, S.E.; Adjei, A.A. Non-small cell lung cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2008, 83, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alduais, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fan, F.; Chen, J.; Chen, B. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A review of risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Medicine 2023, 102, e32899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, R.; Paulus, R.; Galvin, J.; Michalski, J.; Straube, W.; Bradley, J.; Fakiris, A.; Bezjak, A.; Videtic, G.; Johnstone, D.; et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA 2010, 303, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potters, L.; Kavanagh, B.; Galvin, J.M.; Hevezi, J.M.; Janjan, N.A.; Larson, D.A.; Mehta, M.P.; Ryu, S.; Steinberg, M.; Timmerman, R.; et al. American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO) and American College of Radiology (ACR) practice guideline for the performance of stereotactic body radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 76, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, P.; Nyman, J.; Hoyer, M.; Wennberg, B.; Gagliardi, G.; Lax, I.; Drugge, N.; Ekberg, L.; Friesland, S.; Johansson, K.A.; et al. Outcome in a prospective phase II trial of medically inoperable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 3290–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezzano, K.M.; Ma, S.J.; Hermann, G.M.; Rivers, C.I.; Gomez-Suescun, J.A.; Singh, A.K. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer: A review. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 10, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, R.D.; Hu, C.; Michalski, J.M.; Bradley, J.C.; Galvin, J.; Johnstone, D.W.; Choy, H. Long-term results of stereotactic body radiation therapy in medically inoperable stage i non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 1287–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videtic, G.M.; Paulus, R.; Singh, A.K.; Chang, J.Y.; Parker, W.; Olivier, K.R.; Timmerman, R.D.; Komaki, R.R.; Urbanic, J.J.; Stephans, K.L.; et al. Long-term Follow-up on NRG Oncology RTOG 0915 (NCCTG N0927): A Randomized Phase 2 Study Comparing 2 Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy Schedules for Medically Inoperable Patients With Stage I Peripheral Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 103, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Zhou, B.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J.; Ding, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G.; Sun, X. Efficacy and safety of stereotactic radiotherapy on elderly patients with stage I-II central non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1235630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, B.R.; Park, H.S.; Harder, E.M.; Rutter, C.E.; Corso, C.D.; Decker, R.H.; Husain, Z.A. Elderly patients undergoing SBRT for inoperable early-stage NSCLC achieve similar outcomes to younger patients. Lung Cancer 2016, 97, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Katsui, K.; Sugiyama, S.; Yoshio, K.; Kuroda, M.; Hiraki, T.; Kiura, K.; Maeda, Y.; Toyooka, S.; Kanazawa, S. Lung stereotactic body radiation therapy for elderly patients aged ≥80 years with pathologically proven early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.; Song, A.; Zhang, S.; Song, Y.; Gao, C.; Jiang, A.; Li, J.; Jiang, P.; Signorovitch, J.; Arunachalam, A.; et al. Clinical and economic impact of recurrence in unresected non-small cell lung cancer treated with primary stereotactic body radiotherapy: A real-world study using SEER-Medicare data. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2025, 31, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, B.J.; Daly, M.E.; Kennedy, E.B.; Antonoff, M.B.; Broderick, S.; Feldman, J.; Jolly, S.; Meyers, B.; Rocco, G.; Rusthoven, C. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for early-stage non–small-cell lung cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology endorsement of the American Society for Radiation Oncology evidence-based guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detterbeck, F.C. The eighth edition TNM stage classification for lung cancer: What does it mean on main street? J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.T. Competing risks data in clinical oncology. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1360266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, A.L.H.; Mou, B.; Owen, D.; Park, S.S.; Nelson, K.; Hallemeier, C.L.; Sio, T.; Garces, Y.I.; Olivier, K.R.; Merrell, K.W. Long-term clinical outcomes and safety profile of SBRT for centrally located NSCLC. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 4, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, A.; Fang, W.; Sun, Y.; Wen, S. Comparison of long-term survival of patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer after surgery vs stereotactic body radiotherapy. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1915724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, H.; Shirato, H.; Nagata, Y.; Hiraoka, M.; Fujino, M.; Gomi, K.; Niibe, Y.; Karasawa, K.; Hayakawa, K.; Takai, Y.; et al. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (HypoFXSRT) for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: Updated results of 257 patients in a Japanese multi-institutional study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2007, 2, S94–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, J.H.; Mhango, G.; Park, H.S.; Marshall, D.C.; Rosenzweig, K.E.; Wang, Q.; Wisnivesky, J.P.; Veluswamy, R.R. Outcomes following SBRT vs. IMRT and 3DCRT for older patients with stage IIA node-negative non-small cell lung cancer> 5 cm. Clin. Lung Cancer 2023, 24, e9–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Referenced with Permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer V.11.2024; © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc.: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2024; All Rights Reserved, NCCN Makes No Warranties of Any Kind Whatsoever Regarding Their Content, Use or Application and Disclaims any Responsibility for Their Application or Use in Any Way. To View the Most Recent and Complete Version of the Guideline; Available online: https://www.nccn.org/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Daly, M.E.; Redman, M.; Simone, C.B., II; Monjazeb, A.M.; Bauman, J.R.; Hesketh, P.; Feliciano, J.; Kashani, R.; Steuer, C.; Ganti, A.K.; et al. SWOG/NRG S1914: A Randomized Phase III Trial of Induction/Consolidation Atezolizumab+SBRT vs. SBRT Alone in High Risk, Early-Stage NSCLC (NCT#04214262). Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2022, 114, e414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, S.K.; Houghton, B.; Robinson, A.G.; Quantin, X.; Wehler, T.; Kowalski, D.; Ahn, M.J.; Erman, M.; Giaccone, G.; Borghaei, H.; et al. KEYNOTE-867: Phase 3, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) with or without Pembrolizumab in Patients with Unresected Stage I or II Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2022, 114, e376–e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.G.; Xing, L.; Tanaka, H.; Tasaka, S.; Badiyan, S.N.; Nasrallah, H.; Biswas, T.; Shtivelband, M.; Schuette, W.; Shi, A. Phase 3 Study of Durvalumab with SBRT for Unresected Stage I/II, Lymph-Node Negative NSCLC (PACIFIC-4/RTOG3515); American Society of Clinical Oncology: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, C.E.; Corso, C.D.; Park, H.S.; Mancini, B.R.; Yeboa, D.N.; Lester-Coll, N.H.; Kim, A.W.; Decker, R.H. Increase in the use of lung stereotactic body radiotherapy without a preceding biopsy in the United States. Lung Cancer 2014, 85, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients with Stage IA Disease (N = 2302) | Patients with Stage IB Disease (N = 454) | Patients with Stage IIA Disease (N = 168) | Patients with Stage IIB Disease (N = 90) | Overall Patients (N = 3014) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age at diagnosis (years), mean ± SD | 77.0 ± 6.4 | 78.1 ± 6.7 | 78.4 ± 7.1 | 79.3 ± 6.7 | 77.3 ± 6.6 |

| Male, N (%) | 835 (36.3%) | 189 (41.6%) | 65 (38.7%) | 48 (53.3%) | 1137 (37.7%) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |||||

| White | 2006 (87.1%) | 396 (87.2%) | 139 (82.7%) | 79 (87.8%) | 2620 (86.9%) |

| Black | 132 (5.7%) | >18 a | 13 (7.7%) | <11 a | 173 (5.7%) |

| Hispanic | 66 (2.9%) | 14 (3.1%) | <11 a | <11 a | 87 (2.9%) |

| Asian | 82 (3.6%) | 15 (3.3%) | <11 a | <11 a | 111 (3.7%) |

| Other | 16 (0.7%) | <11 a | <11 a | <11 a | 23 (0.8%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Histology type, N (%) | |||||

| Squamous | 727 (31.6%) | 174 (38.3%) | 79 (47.0%) | 42 (46.7%) | 1022 (33.9%) |

| Non-squamous | 1182 (51.3%) | 225 (49.6%) | >70 a | >35 a | 1525 (50.6%) |

| NOS | 393 (17.1%) | 55 (12.1%) | >15 a | <11 a | 467 (15.5%) |

| SBRT index year, N (%) | |||||

| 2007–2011 | 328 (14.2%) | 59 (13.0%) | 26 (15.5%) | 14 (15.6%) | 427 (14.2%) |

| 2012–2016 | 1008 (43.8%) | 220 (48.5%) | 93 (55.4%) | 33 (36.7%) | 1354 (44.9%) |

| 2017–2020 | 966 (42.0%) | 175 (38.5%) | 49 (29.2%) | 43 (47.8%) | 1233 (40.9%) |

| CCI, mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 1.8 | 2.7 ± 1.9 | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 2.4 ± 1.7 |

| Biopsy Type | Patients Who Received Biopsy Within 12 Months Before Primary SBRT Initiation |

|---|---|

| Total | 2715 (90.1%) |

| Lung biopsy, N (%) | |

| Fine needle biopsy | 539 (19.9%) |

| Percutaneous biopsy | 2252 (82.9%) |

| Surgical biopsy | <11 b |

| Bronchial biopsy | 794 (29.2%) |

| Other lung biopsy | >68 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rai, P.; Zhang, S.; Song, Y.; Gao, C.; Jiang, A.; Li, J.; Jiang, P.; Signorovitch, J.; Arunachalam, A.; Song, A.; et al. Real-World Clinical Outcomes and Biopsy Patterns of Older Patients with Unresected Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Primary Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238604

Rai P, Zhang S, Song Y, Gao C, Jiang A, Li J, Jiang P, Signorovitch J, Arunachalam A, Song A, et al. Real-World Clinical Outcomes and Biopsy Patterns of Older Patients with Unresected Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Primary Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238604

Chicago/Turabian StyleRai, Pragya, Su Zhang, Yan Song, Chi Gao, Anya Jiang, Jiayang Li, Peixi Jiang, James Signorovitch, Ashwini Arunachalam, Andrew Song, and et al. 2025. "Real-World Clinical Outcomes and Biopsy Patterns of Older Patients with Unresected Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Primary Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238604

APA StyleRai, P., Zhang, S., Song, Y., Gao, C., Jiang, A., Li, J., Jiang, P., Signorovitch, J., Arunachalam, A., Song, A., Samkari, A., & Daly, M. E. (2025). Real-World Clinical Outcomes and Biopsy Patterns of Older Patients with Unresected Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Primary Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8604. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238604