ZTE MRI for Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy: Integrated Bone–Muscle Analysis and Its Association with Pseudoparesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

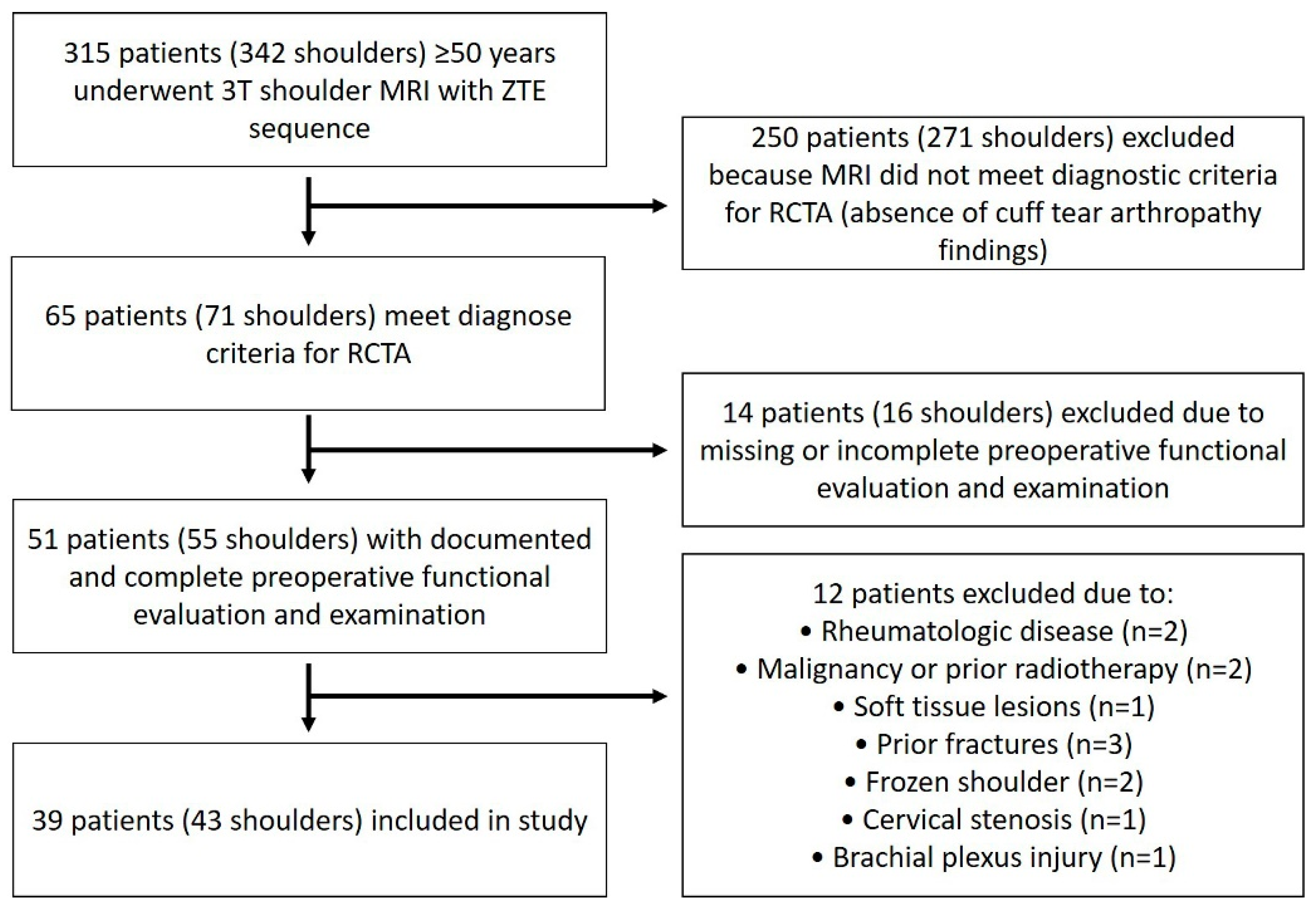

2. Materials and Methods

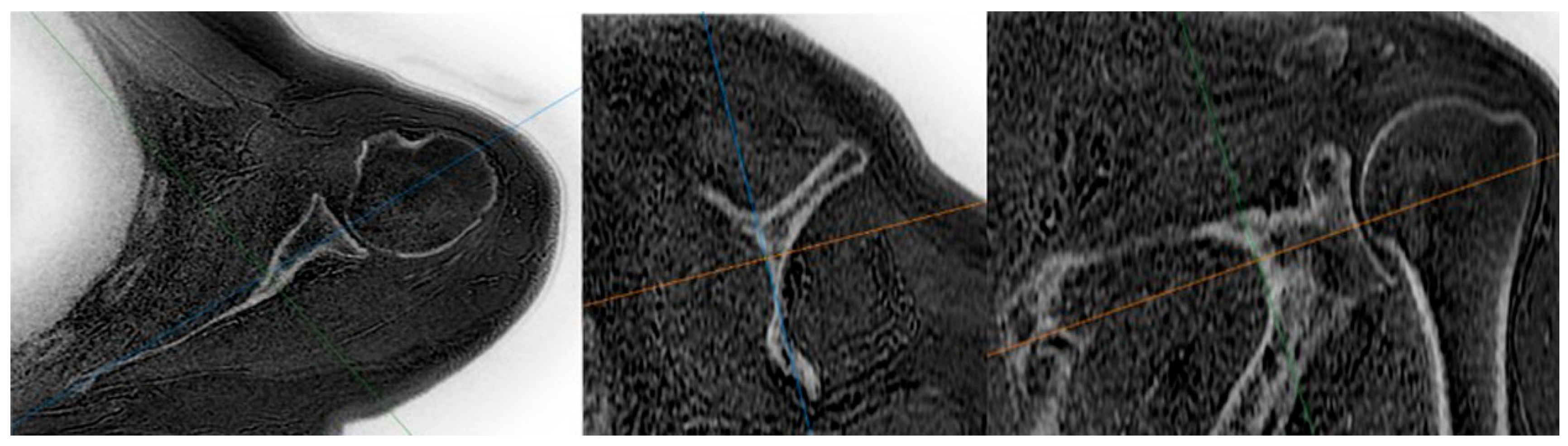

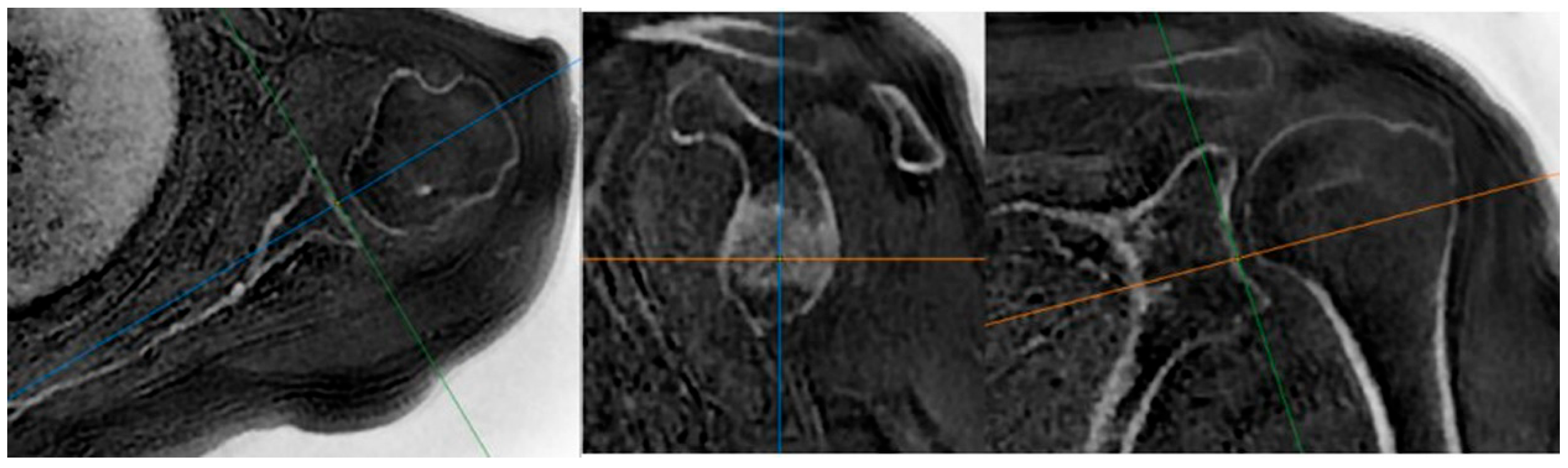

- MRI examinations

- Training and measurement sessions

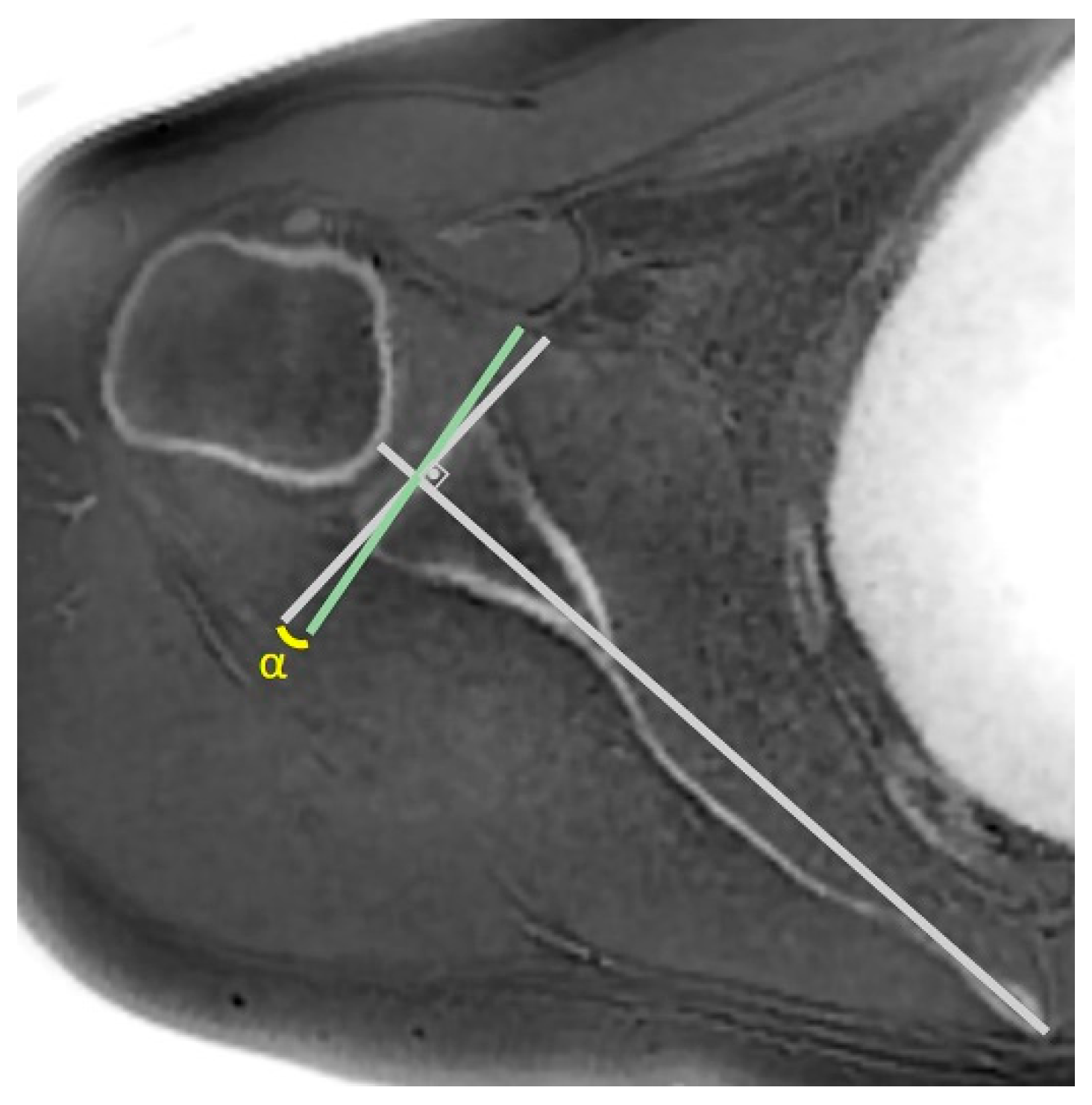

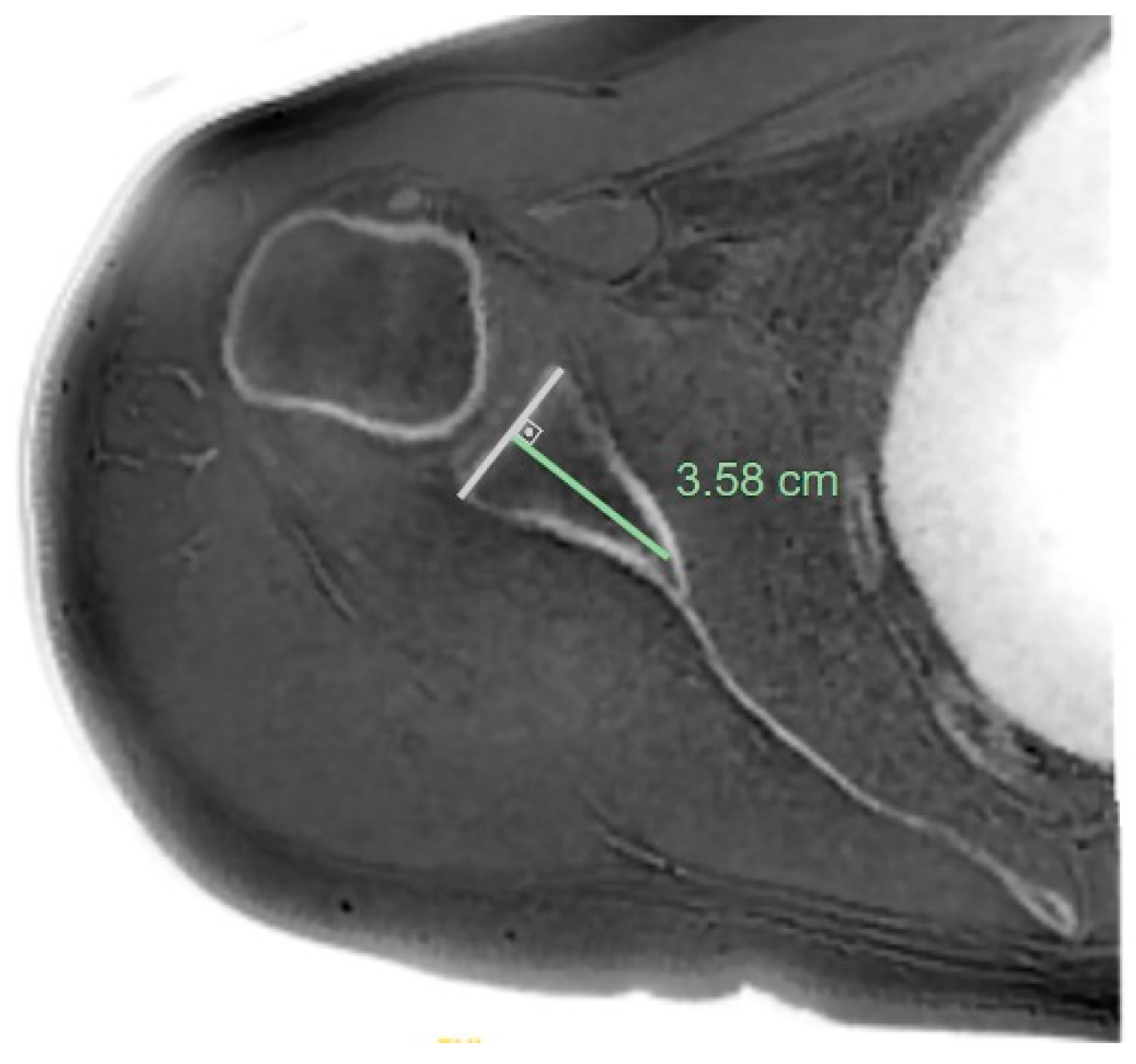

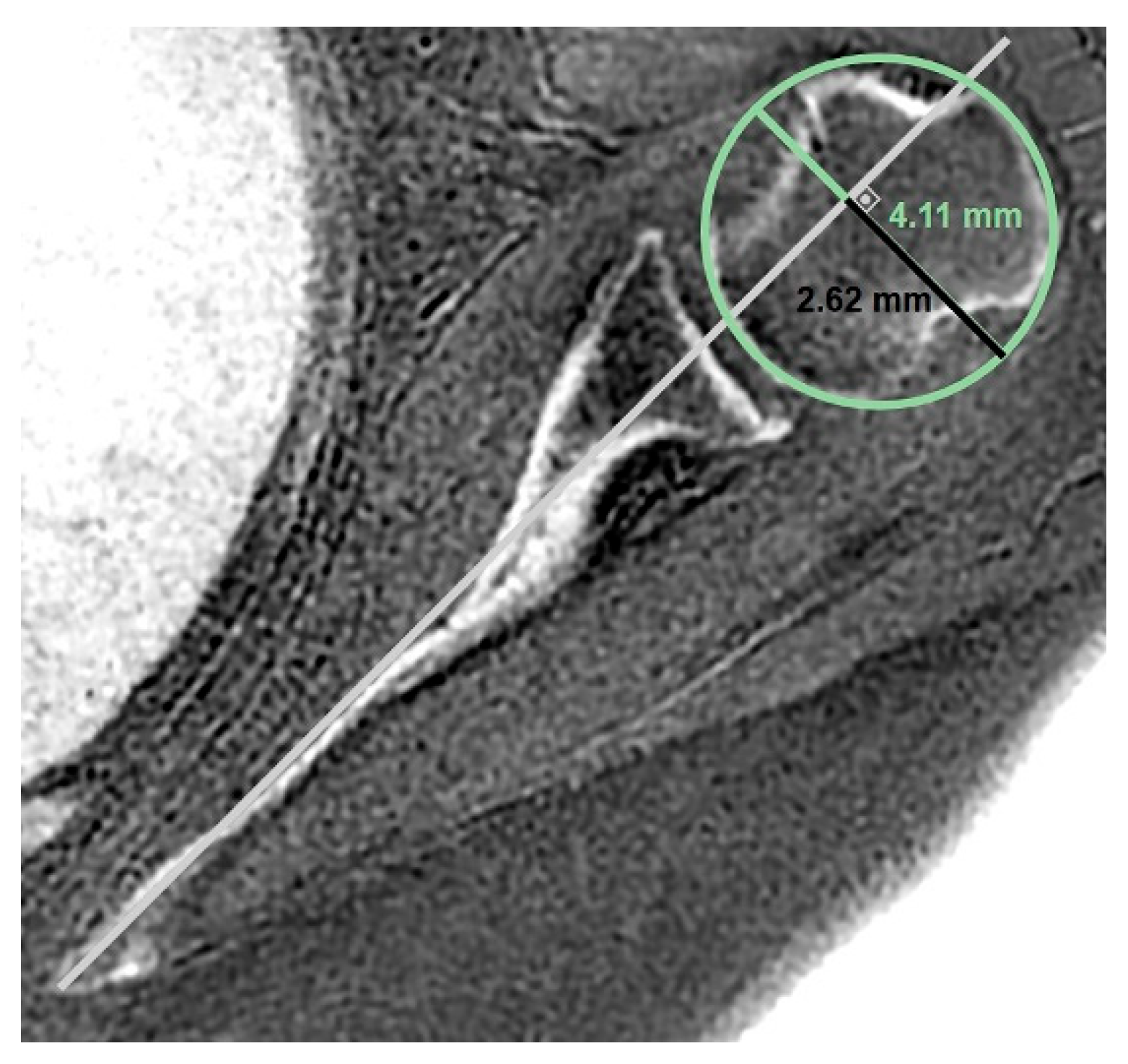

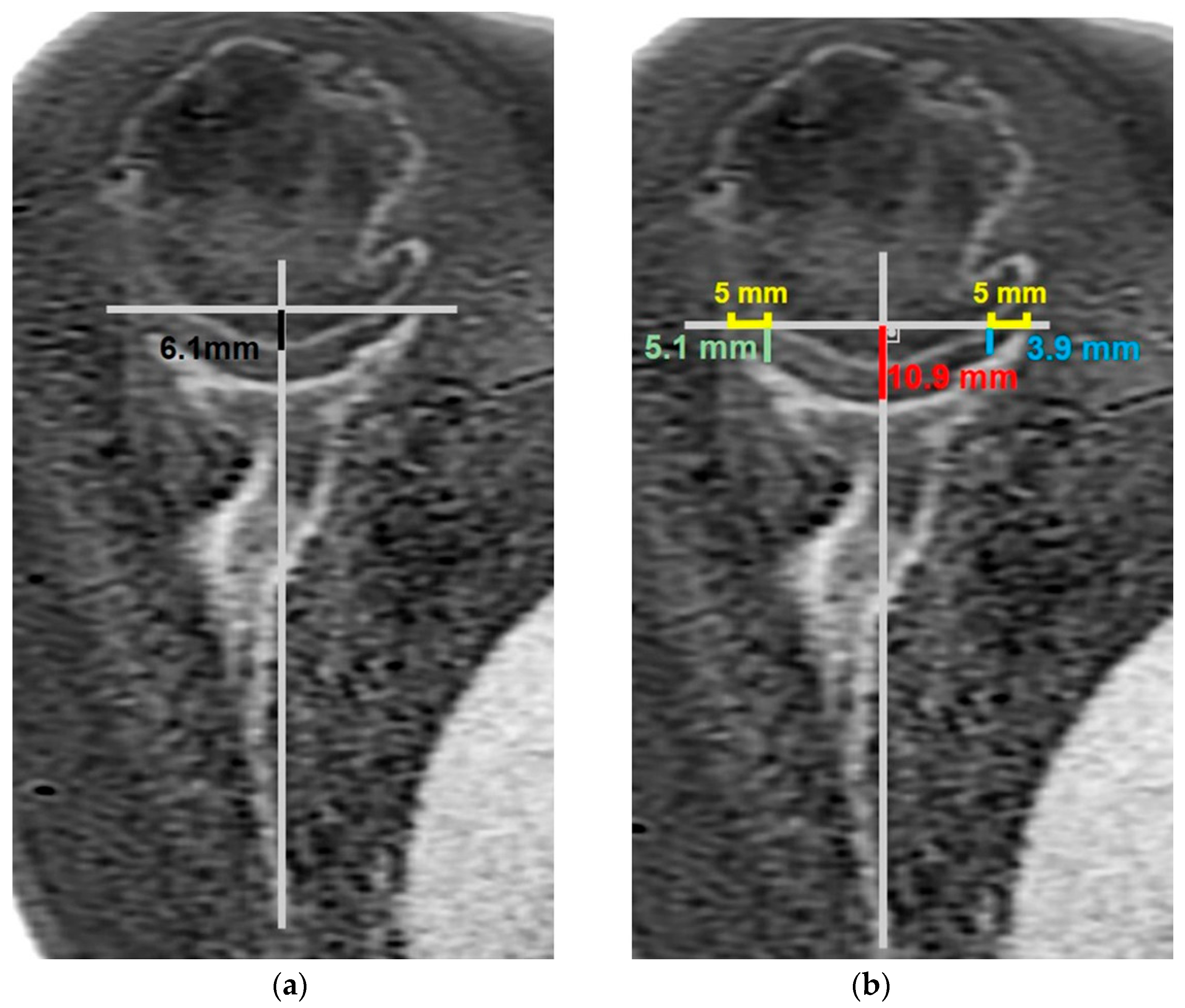

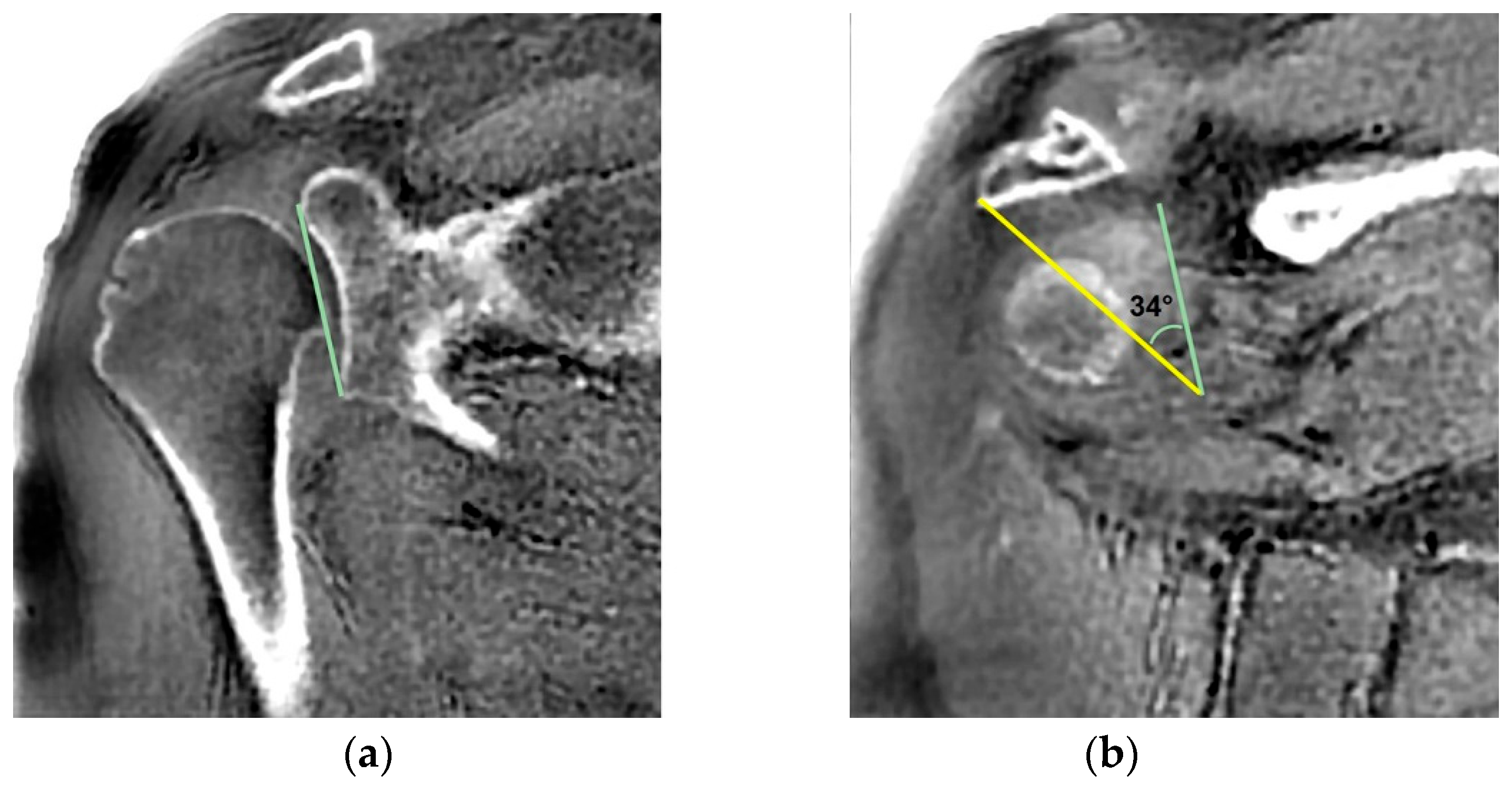

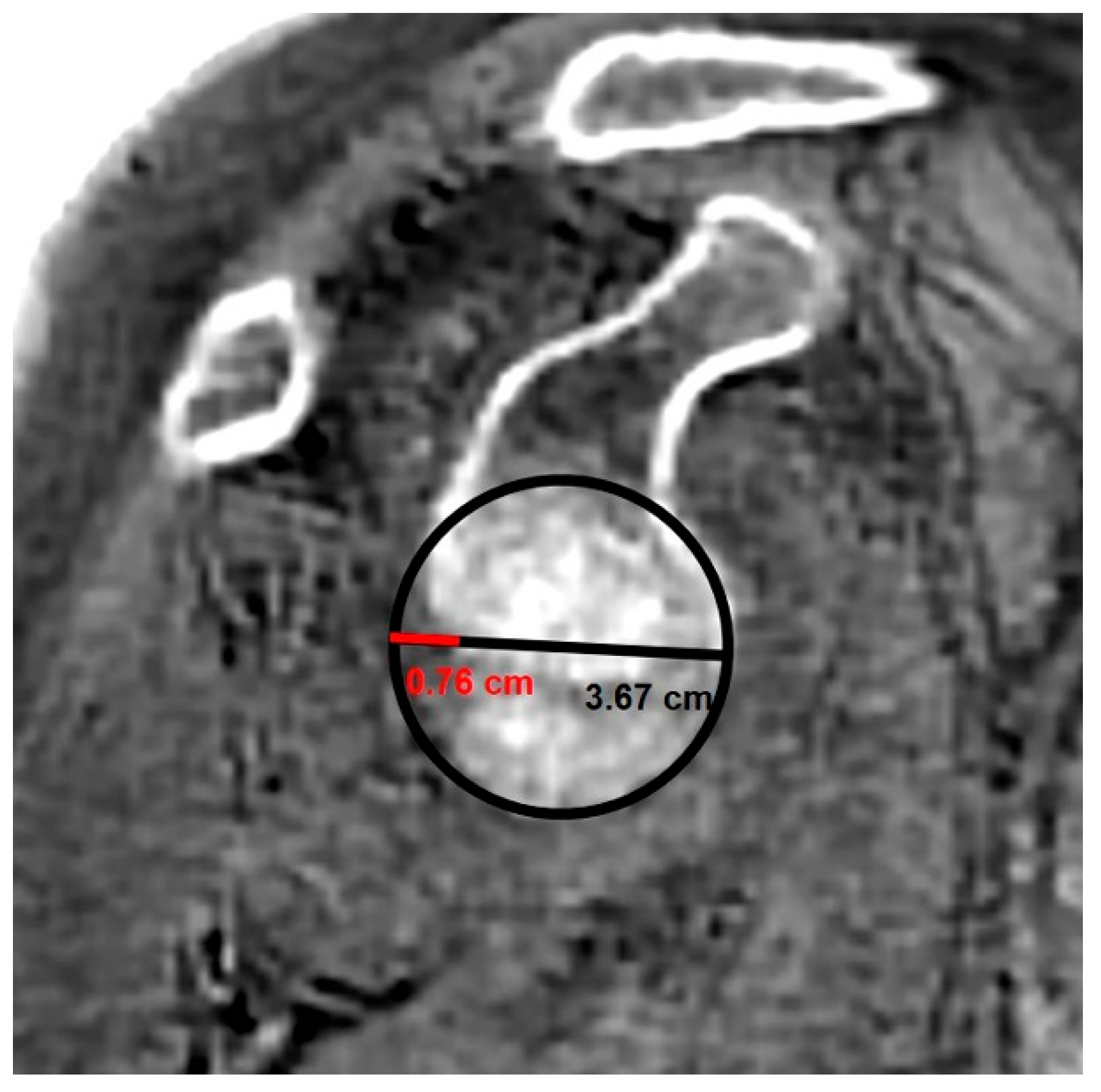

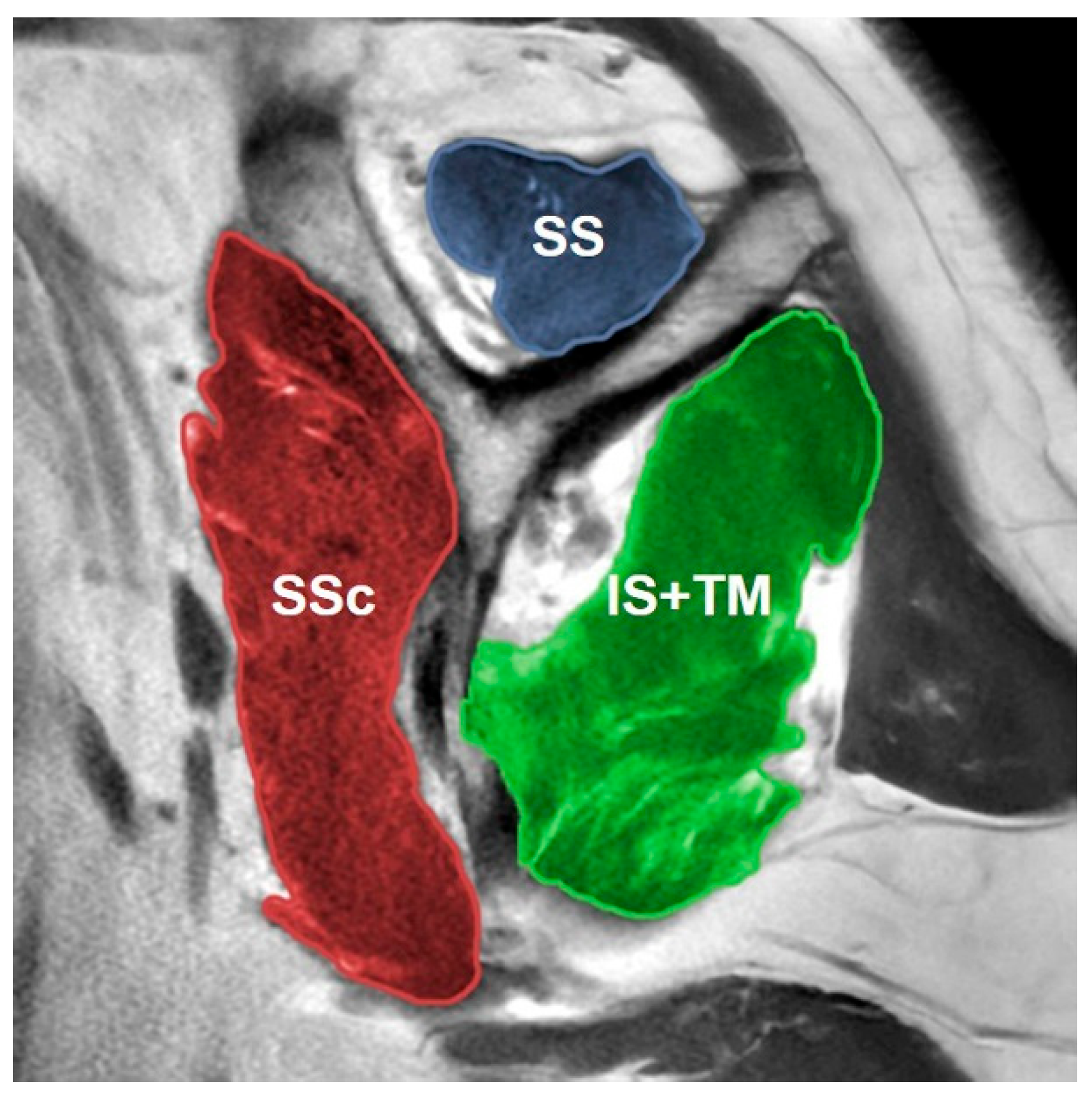

- MRI-based measurements

- Statistical analysis

- Power analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neer, C., 2nd; Craig, E.; Fukuda, H. Cuff-tear arthropathy. JBJS 1983, 65, 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklund, K.J.; Lee, T.Q.; Tibone, J.; Gupta, R. Rotator cuff tear arthropathy. JAAOS-J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2007, 15, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, E.G.; Huri, G.; Hyun, Y.S.; Petersen, S.A.; Srikumaran, U. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty without bone-grafting for severe glenoid bone loss in patients with osteoarthritis and intact rotator cuff. JBJS 2016, 98, 1801–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.D.; Bahu, M.J.; Gardner, T.R.; Dyrszka, M.D.; Levine, W.N.; Bigliani, L.U.; Ahmad, C.S. Simulation of surgical glenoid resurfacing using three-dimensional computed tomography of the arthritic glenohumeral joint: The amount of glenoid retroversion that can be corrected. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2009, 18, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, J.-M.; Jeon, I.-H.; Kim, H.; Choi, S.; Lee, H.; Koh, K.H. Patient-specific instrumentation improves the reproducibility of preoperative planning for the positioning of baseplate components with reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: A comparative clinical study in 39 patients. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2022, 31, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henninger, H.B.; Christensen, G.V.; Taylor, C.E.; Kawakami, J.; Hillyard, B.S.; Tashjian, R.Z.; Chalmers, P.N. The muscle cross-sectional area on MRI of the shoulder can predict muscle volume: An MRI study in Cadavers. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2020, 478, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yubran, A.P.; Pesquera, L.C.; Juan, E.L.S.; Saralegui, F.I.; Canga, A.C.; Camara, A.C.; Valdivieso, G.M.; Pisanti Lopez, C. Rotator cuff tear patterns: MRI appearance and its surgical relevance. Insights Imaging 2024, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erber, B.; Hesse, N.; Glaser, C.; Baur-Melnyk, A.; Goller, S.; Ricke, J.; Heuck, A. MR imaging detection of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: Impact of intravenous contrast administration and reader’s experience on diagnostic performance. Skelet. Radiol. 2022, 51, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydıngöz, Ü.; Yıldız, A.E.; Ergen, F.B. Zero echo time musculoskeletal MRI: Technique, optimization, applications, and pitfalls. Radiographics 2022, 42, 1398–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breighner, R.E.; Endo, Y.; Konin, G.P.; Gulotta, L.V.; Koff, M.F.; Potter, H.G. Technical developments: Zero echo time imaging of the shoulder: Enhanced osseous detail by using MR imaging. Radiology 2018, 286, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mello, R.A.F.; Ma, Y.-j.; Ashir, A.; Jerban, S.; Hoenecke, H.; Carl, M.; Du, J.; Chang, E.Y. Three-dimensional zero echo time magnetic resonance imaging versus 3-dimensional computed tomography for glenoid bone assessment. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2020, 36, 2391–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, A.E.; Yaraşır, Y.; Huri, G.; Aydıngöz, Ü. Optimization of the Grashey view radiograph for critical shoulder angle measurement: A reliability assessment with zero echo time MRI. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2022, 10, 23259671221109522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydıngöz, Ü.; Yıldız, A.E.; Huri, G. Glenoid Track Assessment at Imaging in Anterior Shoulder Instability: Rationale and Step-by-Step Guide. RadioGraphics 2023, 43, e230030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carretero-Gómez, L.; Fung, M.; Wiesinger, F.; Carl, M.; McKinnon, G.; de Arcos, J.; Mandava, S.; Arauz, S.; Sánchez-Lacalle, E.; Nagrani, S. Deep learning-enhanced zero echo time MRI for glenohumeral assessment in shoulder instability: A comparative study with CT. Skelet. Radiol. 2025, 54, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, T.; Tasaki, A.; Mashimo, S.; Moriya, M.; Yamashita, D.; Nozaki, T.; Kitamura, N.; Inaba, Y. Evaluation of glenoid morphology and bony Bankart lesion in shoulders with traumatic anterior instability using zero echo time magnetic resonance imaging. JSES Int. 2024, 8, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, Y.E.; Özer, T.; Anik, Y.; Balci, S.; Aydin, D.; Şahin, N.; Sönmez, H.E. Assessment of sacroiliitis using zero echo time magnetic resonance imaging: A comprehensive evaluation. Pediatr. Radiol. 2025, 55, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecouvet, F.E.; Zan, D.; Lepot, D.; Chabot, C.; Vekemans, M.-C.; Duchêne, G.; Chiabai, O.; Triqueneaux, P.; Kirchgesner, T.; Taihi, L. MRI-based zero echo time and black bone pseudo-CT compared with whole-body CT to detect osteolytic lesions in multiple myeloma. Radiology 2024, 313, e231817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Liang, C.; Sui, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Nie, L.; Song, L. Bone assessment of the sacroiliac joint in ankylosing spondylitis: Comparison between computed tomography and zero echo time MRI. Eur. J. Radiol. 2024, 181, 111743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokish, J.M.; Alexander, T.C.; Kissenberth, M.J.; Hawkins, R.J. Pseudoparalysis: A systematic review of term definitions, treatment approaches, and outcomes of management techniques. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2017, 26, e177–e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwend, N.; Ivošević-Radovanović, D.; Patte, D. Rotator cuff tear—Relationship between clinical and anatomopathological findings. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 1987, 107, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.; Steinmann, P.; Gilbart, M.; Gerber, C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. JBJS 2005, 87, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar]

- Tokish, J.M.; Brinkman, J.C. Pseudoparalysis and pseudoparesis of the shoulder: Definitions, management, and outcomes. JAAOS-J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2024, 32, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denard, P.J.; Koo, S.S.; Murena, L.; Burkhart, S.S. Pseudoparalysis: The importance of rotator cable integrity. Orthopedics 2012, 35, e1353–e1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collin, P.; Matsumura, N.; Lädermann, A.; Denard, P.J.; Walch, G. Relationship between massive chronic rotator cuff tear pattern and loss of active shoulder range of motion. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2014, 23, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, K.; Rahm, S.; Schubert, M.; Fischer, M.A.; Farshad, M.; Gerber, C.; Meyer, D.C. Fluoroscopic, magnetic resonance imaging, and electrophysiologic assessment of shoulders with massive tears of the rotator cuff. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2015, 24, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.J.; Golijanin, P.; Dumont, G.D.; Parada, S.A.; Vopat, B.G.; Reinert, S.E.; Romeo, A.A.; Provencher, C.M.T. The effect of sagittal rotation of the glenoid on axial glenoid width and glenoid version in computed tomography scan imaging. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2016, 25, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, M.J.; Chalian, M.; Sharifi, A.; Pezeshk, P.; Xi, Y.; Lawson, P.; Chhabra, A. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of glenoid bone stock and glenoid version: Inter-reader analysis and correlation with rotator cuff tendinopathy and atrophy in patients with shoulder osteoarthritis. Skelet. Radiol. 2020, 49, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R.J.; Hawthorne, K.; Genez, B. The use of computerized tomography in the measurement of glenoid version. JBJS 1992, 74, 1032–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernstbrunner, L.; El Nashar, R.; Favre, P.; Bouaicha, S.; Wieser, K.; Gerber, C. Chronic pseudoparalysis needs to be distinguished from pseudoparesis: A structural and biomechanical analysis. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanatlı, U.; Ayas, İ.H.; Tokgöz, M.A.; Bahadır, B. Does the extent of tear influence pseudoparesis in patients with isolated subscapularis tears? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2024, 482, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawano, Y.; Matsumura, N.; Murai, A.; Tada, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Nakamura, M.; Nagura, T. Evaluation of the translation distance of the glenohumeral joint and the function of the rotator cuff on its translation: A cadaveric study. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2018, 34, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.C.; Yoo, S.J.; Jo, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Baek, E.; Lee, S.M.; Yoo, J.C. The impact of supraspinatus tear on subscapularis muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration. Clin. Shoulder Elb. 2024, 27, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giacomo, G.; Pouliart, N.; Costantini, A.; De Vita, A. Atlas of Functional Shoulder Anatomy; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moor, B.; Bouaicha, S.; Rothenfluh, D.; Sukthankar, A.; Gerber, C. Is there an association between the individual anatomy of the scapula and the development of rotator cuff tears or osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint?: A radiological study of the critical shoulder angle. Bone Jt. J. 2013, 95, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Patel, M.; Abboud, J.A.; Horneff, J.G., III. The effect of critical shoulder angle on functional compensation in the setting of cuff tear arthropathy. JSES Int. 2020, 4, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuberer, P.R.; Plachel, F.; Willinger, L.; Moroder, P.; Laky, B.; Pauzenberger, L.; Lomoschitz, F.; Anderl, W. Critical shoulder angle combined with age predict five shoulder pathologies: A retrospective analysis of 1000 cases. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puel, U.; Lombard, C.; Hossu, G.; Louis, M.; Blum, A.; Teixeira, P.A.G.; Gillet, R. Zero echo time MRI in shoulder MRI protocols for the diagnosis of rotator cuff calcific tendinopathy improves identification of calcific deposits compared to conventional MR sequences but remains sub-optimal compared to radiographs. Eur. Radiol. 2023, 33, 6381–6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensle, F.; Kaniewska, M.; Lohezic, M.; Guggenberger, R. Enhanced bone assessment of the shoulder using zero-echo time MRI with deep-learning image reconstruction. Skelet. Radiol. 2024, 53, 2597–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damas, C.N.; Silva, J.; Sá, M.C.; Torres, J. Computed tomography morphological analysis of the scapula and its implications in shoulder arthroplasty. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2016, 26, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuki, K.; Sugaya, H.; Hoshika, S.; Ueda, Y.; Takahashi, N.; Tokai, M.; Banks, S.A. Three-dimensional measurement of glenoid dimensions and orientations. J. Orthop. Sci. 2019, 24, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-H.; Gwak, H.-C.; Kim, C.-W.; Lee, C.-R.; Kwon, Y.-U.; Seo, H.-W. Difference of critical shoulder angle (CSA) according to minimal rotation: Can minimal rotation of the scapula be allowed in the evaluation of CSA? Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2019, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouaicha, S.; Ehrmann, C.; Slankamenac, K.; Regan, W.D.; Moor, B.K. Comparison of the critical shoulder angle in radiographs and computed tomography. Skelet. Radiol. 2014, 43, 1053–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.-H.; Kim, H.-C.; Kang, D.; Kim, J.-Y. Comparative study of glenoid version and inclination using two-dimensional images from computed tomography and three-dimensional reconstructed bone models. Clin. Shoulder Elb. 2020, 23, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.J.; Kunkle, B.F.; Greene, A.T.; Eichinger, J.K.; Friedman, R.J. Variability and reliability of 2-dimensional vs. 3-dimensional glenoid version measurements with 3-dimensional preoperative planning software. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2022, 31, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidder, J.F.; Rouleau, D.M.; Pons-Villanueva, J.; Dynamidis, S.; DeFranco, M.J.; Walch, G. Humeral head posterior subluxation on CT scan: Validation and comparison of 2 methods of measurement. Tech. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2010, 11, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyton, L.; Gröger, F.; Rattier, S.; Hirakawa, Y. Walch B2 glenoids: 2-dimensional vs 3-dimensional comparison of humeral head subluxation and glenoid retroversion. JSES Int. 2022, 6, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacxsens, M.; Karns, M.R.; Henninger, H.B.; Drew, A.J.; Van Tongel, A.; De Wilde, L. Guidelines for humeral subluxation cutoff values: A comparative study between conventional, reoriented, and three-dimensional computed tomography scans of healthy shoulders. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2018, 27, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matache, B.A.; Alnusif, N.; Chaoui, J.; Walch, G.; Athwal, G.S. Humeral head subluxation in Walch type B shoulders varies across imaging modalities. JSES Int. 2021, 5, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibayama, Y.; Imamura, R.; Hirose, T.; Sugi, A.; Mizushima, E.; Watanabe, Y.; Tomii, R.; Emori, M.; Teramoto, A.; Iba, K. Reliability and accuracy of the critical shoulder angle measured by anteroposterior radiographs: Using digitally reconstructed radiograph from 3-dimensional computed tomography images. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2023, 32, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wilde, L.; Berghs, B.M.; Audenaert, E.; Sys, G.; Van Maele, G.; Barbaix, E. About the variability of the shape of the glenoid cavity. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2004, 26, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charousset, C.; Beauthier, V.; Bellaïche, L.; Guillin, R.; Brassart, N.; Thomazeau, H.; Society, F.A. Can we improve radiological analysis of osseous lesions in chronic anterior shoulder instability? Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2010, 96, S88–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.K.; Griffith, J.F.; Tong, M.M.; Sharma, N.; Yung, P. Glenoid bone loss: Assessment with MR imaging. Radiology 2013, 267, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Sun, S.; Chen, H. Zero echo time vs. T1-weighted MRI for assessment of cortical and medullary bone morphology abnormalities using CT as the reference standard. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2023, 58, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Hou, B.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.V.; Li, X. Comparison of zero echo time MRI with T1-weighted fast spin echo for the recognition of sacroiliac joint structural lesions using CT as the reference standard. Eur. Radiol. 2022, 32, 3963–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breighner, R.E.; Bogner, E.A.; Lee, S.C.; Koff, M.F.; Potter, H.G. Evaluation of osseous morphology of the hip using zero echo time magnetic resonance imaging. Am. J. Sports Med. 2019, 47, 3460–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measurement | Intraobserver Agreement | Interobserver Agreement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | %95 CI | p | ICC | %95 CI | p | |

| Glenoid version | 0.906 | 0.826–0.949 | >0.05 | 0.906 | 0.811–0.951 | >0.05 |

| Glenoid vault depth | 0.905 | 0.824–0.948 | >0.05 | 0.705 | 0.497–0.833 | >0.05 |

| Humeral subluxation index | 0.877 | 0.773–0.933 | >0.05 | 0.846 | 0.745–0.912 | >0.05 |

| Humerus head medialization | 0.893 | 0.507–0.976 | >0.05 | 0.857 | 0.573–0.965 | >0.05 |

| Anterior bone loss | 0.917 | 0.776–0.969 | >0.05 | 0.670 | 0.235–0.876 | >0.05 |

| Central bone loss | 0.949 | 0.862–0.981 | >0.05 | 0.788 | 0.525–0.919 | >0.05 |

| Posterior bone loss | 0.925 | 0.748–0.974 | >0.05 | 0.802 | 0.551–0.924 | >0.05 |

| Critical shoulder angle | 0.914 | 0.838–0.954 | >0.05 | 0.945 | 0.845–0.947 | >0.05 |

| Best-fit circle width | 0.863 | 0.746–0.926 | >0.05 | 0.828 | 0.619–0.916 | >0.05 |

| Glenoid best-fit circle bone loss ratio | 0.818 | 0.546–0.927 | >0.05 | 0.640 | 0.292–0.836 | >0.05 |

| Parameter | Constant–Murley Score | ASES Score | Forward Elevation | Abduction | External Rotation | Internal Rotation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glenoid version | r | −0.118 | −0.205 | −0.164 | −0.258 | −0.123 | −0.280 |

| p | 0.452 a | 0.187 a | 0.294 a | 0.095 a | 0.432 a | 0.069 a | |

| Glenoid vault depth | r | 0.096 | 0.263 | 0.133 | 0.108 | 0.082 | 0.047 |

| p | 0.542 b | 0.089 b | 0.396 a | 0.493 a | 0.600 a | 0.765 a | |

| Humeral subluxation index | r | 0.099 | 0.055 | −0.028 | −0.074 | −0.068 | −0.037 |

| p | 0.529 a | 0.726 a | 0.859 a | 0.637 a | 0.664 a | 0.812 a | |

| Humeral head medialization | r | −0.175 | −0.238 | −0.274 | −0.314 * | 0.185 | −0.194 |

| p | 0.262 a | 0.124 a | 0.076 a | 0.040 a | 0.234 a | 0.213 a | |

| Anterior bone loss | r | −0.322 * | −0.327 * | −0.411 * | −0.475 * | −0.040 | −0.277 |

| p | 0.035 a | 0.032 a | 0.006 a | 0.001 a | 0.801 a | 0.072 a | |

| Central bone loss | r | −0.170 | −0.194 | −0.268 | −0.354 * | 0.018 | −0.225 |

| p | 0.277 a | 0.213 a | 0.082 a | 0.020 a | 0.910 a | 0.147 a | |

| Posterior bone loss | r | −0.177 | −0.184 | −0.259 | −0.354 * | −0.009 | −0.271 |

| p | 0.258 a | 0.237 a | 0.093 a | 0.020 a | 0.953 a | 0.079 a | |

| Critical shoulder angle | r | −0.275 | −0.163 | −0.140 | −0.155 | −0.026 | −0.182 |

| p | 0.074 a | 0.296 a | 0.369 a | 0.321 a | 0.869 a | 0.242 a | |

| Best-fit circle bone loss ratio | r | 0.005 | −0.066 | −0.043 | −0.100 | 0.040 | −0.097 |

| p | 0.972 a | 0.673 a | 0.785 a | 0.522 a | 0.798 a | 0.535 a | |

| SS cross-sectional area | r | 0.228 | 0.284 | 0.198 | 0.238 | 0.081 | 0.207 |

| p | 0.141 a | 0.065 a | 0.203 b | 0.125 b | 0.606 b | 0.183 b | |

| SSc cross-sectional area | r | 0.495 * | 0.460 * | 0.471 * | 0.447 * | 0.240 | 0.464 * |

| p | 0.001 b | 0.002 b | 0.001 b | 0.003 b | 0.121 b | 0.002 b | |

| IS + TM cross-sectional area | r | 0.295 | 0.274 | 0.209 b | 0.243 | 0.155 | 0.211 |

| p | 0.055 b | 0.075 b | 0.178 b | 0.116 b | 0.322 b | 0.173 b | |

| SSc/IS + TM ratio | r | 0.180 | 0.175 | 0.276 b | 0.192 | 0.036 | 0.227 |

| p | 0.249 b | 0.261 b | 0.074 b | 0.218 b | 0.820 b | 0.144 b | |

| Parameter | Pseudoparesis Group (n = 27) | Nonparesis Group (n = 16) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| SS cross-sectional area, cm2 | 2.92 ± 0.73 | 3.42 ± 1.16 | 0.089 a |

| SSc cross-sectional area, cm2 | 9.65 ± 2.93 | 11.78 ± 2.83 | 0.006 b |

| IS + TM cross-sectional area, cm2 | 8.98 ± 2.54 | 10.17 ± 2.59 | 0.090 b |

| SSc/(IS + TM) ratio | 1.08 ± 0.18 | 1.19 ± 0.28 | 0.258 b |

| Glenoid version, degrees (°) | 6.04 ± 5.28 | 5.50 ± 5.75 | 0.562 b |

| Glenoid vault depth, cm | 2.08 ± 0.18 | 2.19 ± 0.31 | 0.131 b |

| Humeral subluxation index | 0.52 ± 0.06 | 0.53 ± 0.07 | 0.970 b |

| Humerus head medialization, mm | 7.04 ± 13.54 | 5.06 ± 17.09 | 0.323 b |

| Anterior bone loss, mm | 11.59 ± 14.40 | 4.25 ± 10.66 | 0.079 b |

| Central bone loss, mm | 18.29 ± 24.41 | 13.44 ± 21.53 | 0.556 b |

| Posterior bone loss, mm | 16.70 ± 22.83 | 13.56 ± 23.70 | 0.664 b |

| Critical shoulder angle, degrees (°) | 33.44 ± 4.68 | 31.60 ± 4.71 | 0.392 b |

| Glenoid best-fit circle bone loss ratio | 4.74 ± 5.27 | 6.02 ± 7.56 | 0.728 b |

| Constant–Murley score | 32.85 ± 10.53 | 55.75 ± 6.76 | 0.154 a |

| ASES score | 34.22 ± 7.96 | 57.12 ± 7.12 | 0.606 a |

| Forward elevation, degrees (°) | 60.63 ± 13.97 | 100.94 ± 6.64 | <0.001 b |

| Abduction degrees (°) | 59.52 ± 13.07 | 98.12 ± 6.02 | <0.001 b |

| External rotation, degrees (°) | 54.44 ± 16.25 | 74.37 ± 6.55 | <0.001 b |

| Internal rotation, degrees (°) | 44 ± 16.45 | 63.37 ± 10.75 | <0.001 b |

| Intraobserver Agreement (ICC) | Interobserver Agreement (ICC) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Current Study | with CT in the Literature | Current Study | with CT in the Literature |

| Glenoid Version | 0.906 | 0.605 [46]–0.99 [28] | 0.906 | 0.456 [46] –0.915 [47] |

| Glenoid Vault Depth | 0.905 | 0.97 [28]–0.976 [43] | 0.877 | 0.19 [42]–0.58 [28]–0.866 [43] |

| Humeral Subluxation Index | 0.846 | 0.841 [48]–0.966 [49] | 0.705 | 0.639 [50]–0.94 [51] |

| Humeral Head Medialization | 0.893 | 0.99 [28] | 0.857 | 0.78 [28] |

| Anterior Bone Loss | 0.917 | 0.99 [28] | 0.67 | 0.78 [28] |

| Central Bone Loss | 0.949 | 0.99 [28] | 0.788 | 0.69 [28] |

| Posterior Bone Loss | 0.925 | 0.99 [28] | 0.802 | 0.78 [28] |

| Critical Shoulder Angle | 0.914 | 0.93 [52] –0.965 [44] | 0.945 | 0.943 [44] –0.989 [45] |

| Best-fit Circle Width | 0.863 | 0.99 [53] | 0.828 | 0.98 [53] |

| Best-fit Circle Bone Loss Ratio | 0.818 | 0.90 [54] 0.95 [55] | 0.64 | 0.74 [54] –0.98 [55] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yılmaz, E.T.; İbik, S.; Yaman, V.; Fındık, Ş.B.; Aydıngöz, Ü.; Huri, G. ZTE MRI for Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy: Integrated Bone–Muscle Analysis and Its Association with Pseudoparesis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8597. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238597

Yılmaz ET, İbik S, Yaman V, Fındık ŞB, Aydıngöz Ü, Huri G. ZTE MRI for Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy: Integrated Bone–Muscle Analysis and Its Association with Pseudoparesis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8597. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238597

Chicago/Turabian StyleYılmaz, Engin Türkay, Serkan İbik, Vedat Yaman, Şeyda Betül Fındık, Üstün Aydıngöz, and Gazi Huri. 2025. "ZTE MRI for Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy: Integrated Bone–Muscle Analysis and Its Association with Pseudoparesis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8597. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238597

APA StyleYılmaz, E. T., İbik, S., Yaman, V., Fındık, Ş. B., Aydıngöz, Ü., & Huri, G. (2025). ZTE MRI for Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy: Integrated Bone–Muscle Analysis and Its Association with Pseudoparesis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8597. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238597