Technological Advances in Intra-Operative Navigation: Integrating Fluorescence, Extended Reality, and Artificial Intelligence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Current State of Surgical Navigation

3. Barriers to Adoption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MIS | Minimally invasive surgery |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| XR | Extended reality |

| VR | Virtual reality |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| MR | Mixed reality |

| FGS | Fluorescence-guided surgery |

| ICG | Indocyanine green |

| GPS | Global positioning system |

References

- Chopra, H.; Munjal, K.; Arora, S.; Bibi, S.; Biswas, P. Role of augmented reality in surgery: Editorial. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 2526–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, L.; Nicolau, S.; Pessaux, P.; Mutter, D.; Marescaux, J. Real-time 3D image reconstruction guidance in liver resection surgery. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2014, 3, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soler, L.; Delingette, H.; Malandain, G.; Ayache, N.; Koehl, C.; Clément, J.M.; Dourthe, O.; Marescaux, J. An automatic virtual patient reconstruction from CT-scans for hepatic surgical planning. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2000, 70, 316–322. [Google Scholar]

- Myles, C.; Gorman, L.; Jones, J.F.X. 3D printing variation: Teaching and assessing hepatobiliary variants in human anatomy. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2025, 18, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, E.C.; Moynihan, A.; Dalli, J.; Khan, M.F.; Singh, S.; McDonald, K.; O’Reilly, J.; Moynagh, N.; Myles, C.; Brannigan, A.; et al. Clinical validation of 3D virtual modelling for laparoscopic complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation for proximal colon cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, E.C.; Moynihan, A.; Khan, M.F.; Lawler, L.; Cahill, R.A. Comparison and impact of preoperative 3D virtual vascular modelling with intraoperative indocyanine green perfusion angiography for personalized proximal colon cancer surgery. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 51, 109581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.P.; Pelanis, E.; Bugge, R.; Brun, H.; Palomar, R.; Aghayan, D.L.; Fretland, Å.A.; Edwin, B.; Elle, O.J. Use of mixed reality for surgery planning: Assessment and development workflow. J. Biomed. Inform. 2020, 112, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, R.A.; Meijer, R.P.J.; Droogh, D.H.M.; Jongbloed, J.J.; Bijlstra, O.D.; Boersma, F.; Braak, J.P.B.M.; Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg, E.; Putter, H.; Holman, F.A.; et al. Indocyanine green near-infrared fluorescence bowel perfusion assessment to prevent anastomotic leakage in minimally invasive colorectal surgery (AVOID): A multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 924–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayne, D.; Croft, J.; Corrigan, N.; Quirke, P.; Cahill, R.A.; Ainsworth, G.; Meads, D.M.; Kirby, A.; Tolan, D.; Gordon, K.; et al. Intraoperative fluorescence angiography with indocyanine green to prevent anastomotic leak in rectal cancer surgery (IntAct): An unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 10, 806–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, K.; Balamurugan, G.; Ravindra, C.; Kodali, R.; Hansalia, D.S.; Rengan, V. The impact of indocyanine green fluorescence angiography (ICG-FA) on anastomotic leak rates and postoperative outcomes in colorectal anastomoses: A systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 2025, 39, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolár, M.; Mišánik, M.; Hošala, M.; Demeter, M.; Janík, J.; Miklušica, J. ICG lymph node mapping in gastric cancer operations. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 109288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, R.C.; Lee, A.M.; Cheverie, J.N.; Zhao, B.; Blitzer, R.R.; Patel, R.J.; Soltero, S.; Sandler, B.J.; Jacobsen, G.R.; Doucet, J.J.; et al. Fluorescent cholangiography significantly improves patient outcomes for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 5729–5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Bos, J.; Schols, R.M.; Boni, L.; Cassinotti, E.; Carus, T.; Luyer, M.D.; Vahrmeijer, A.L.; Mieog, J.S.D.; Warnaar, N.; Berrevoet, F.; et al. Near-infrared fluorescence cholangiography assisted laparoscopic cholecystectomy (FALCON): An international multicentre randomized controlled trial. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 4574–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, R.; Ryan, E.J.; Harding, T.; Cahill, R.A. Ureteric safeguarding in colorectal resection with indocyanine green visualization: A video vignette. Color. Dis. 2025, 27, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

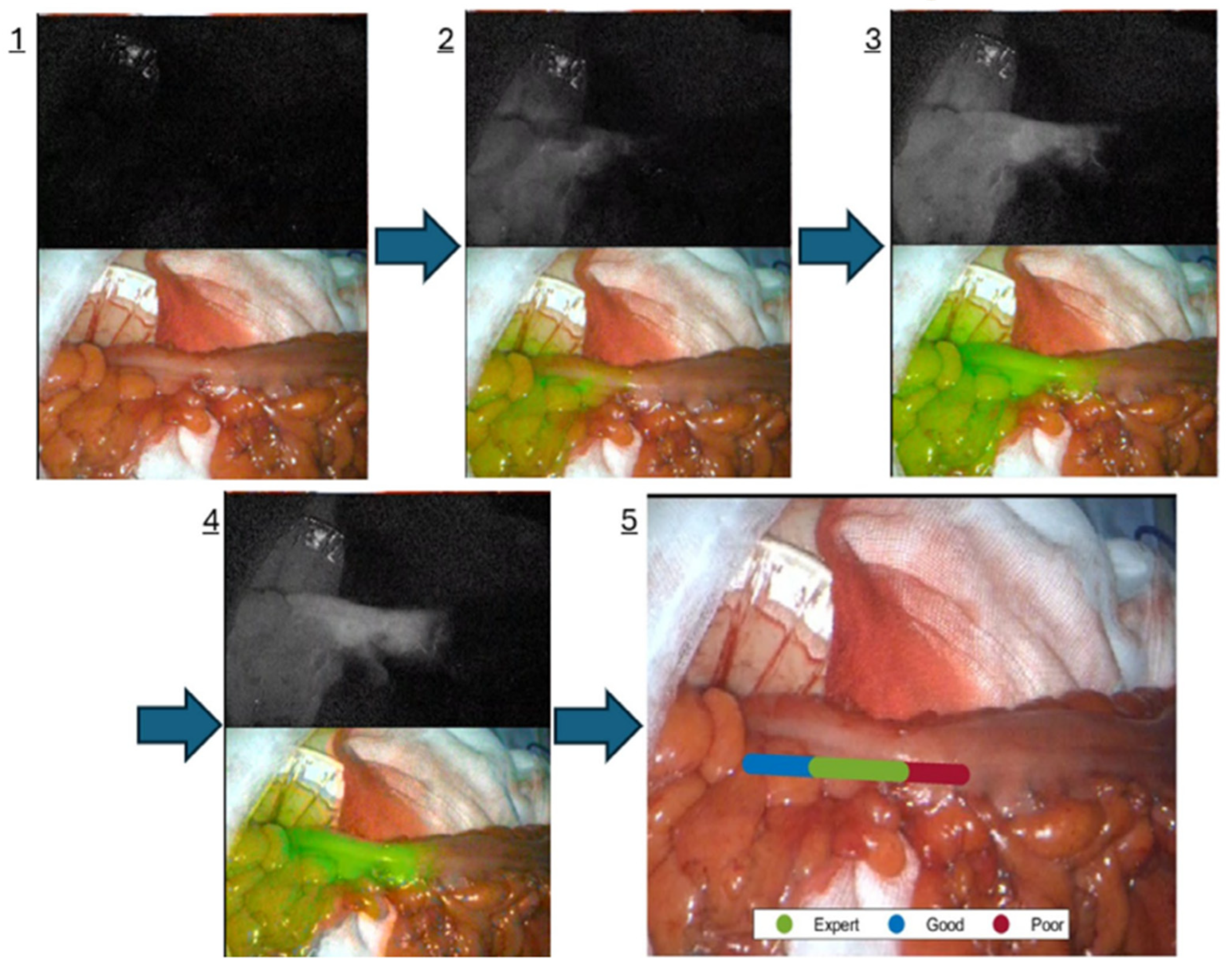

- Mc Entee, P.D.; Boland, P.A.; Cahill, R.A. AUGUR-AIM: Clinical validation of an artificial intelligence indocyanine green fluorescence angiography expert representer. Color. Dis. 2025, 27, e70097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josserand, V.; Bernard, C.; Michy, T.; Guidetti, M.; Vollaire, J.; Coll, J.L.; Hurbin, A. Tumor-Specific Imaging with Angiostamp800 or Bevacizumab-IRDye 800CW Improves Fluorescence-Guided Surgery over Indocyanine Green in Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA Approves Pafolacianine for Identifying Malignant Ovarian Cancer Lesions. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-pafolacianine-identifying-malignant-ovarian-cancer-lesions (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Boland, P.A.; Hardy, N.P.; Moynihan, A.; McEntee, P.D.; Loo, C.; Fenlon, H.; Cahill, R.A. Intraoperative near infrared functional imaging of rectal cancer using artificial intelligence methods-now and near future state of the art. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 3135–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Hoven, P.; Tange, F.; Van Der Valk, J.; Nerup, N.; Putter, H.; Van Rijswijk, C.; Van Schaik, J.; Schepers, A.; Vahrmeijer, A.; Hamming, J.; et al. Normalization of Time-Intensity Curves for Quantification of Foot Perfusion Using Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging With Indocyanine Green. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2023, 30, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Keulen, S.; Hom, M.; White, H.; Rosenthal, E.L.; Baik, F.M. The Evolution of Fluorescence-Guided Surgery. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2023, 25, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Qiu, R.; Yang, H.; Ren, F.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, C. Advanced NIR ratiometric probes for intravital biomedical imaging. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 17, 14107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, C.; Li, P.; Fu, Q. Ratiometric optical probes for biosensing. Theranostics 2023, 13, 2632–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Yan, J.; Gao, X.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Shang, Y.; Tang, X. Using Virtual Reality to Enhance Surgical Skills and Engagement in Orthopedic Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e70266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesch, H.; Johnson, E.; Peters, J.; Cendán, J.C. VR Simulation Leads to Enhanced Procedural Confidence for Surgical Trainees. J. Surg. Educ. 2020, 77, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadzadeh Tabrizi, N.; Lin, N.; Polkampally, S.; Kuchibhotla, S.; Lin, Y. Gamification to enhance clinical and technical skills in surgical residency: A systematic review. Am. J. Surg. 2025, 246, 116339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJgosse, W.; van Goor, H.; Rosman, C.; Luursema, J.M. Construct Validity of a Serious Game for Laparoscopic Skills Training: Validation Study. JMIR Serious Games 2020, 8, e17222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer-Szary, J.; Luis, M.S.; Mikulski, S.; Patel, A.; Schulz, F.; Tretiakow, D.; Fercho, J.; Jaguszewska, K.; Frankiewicz, M.; Pawłowska, E.; et al. The Role of 3D Printing in Planning Complex Medical Procedures and Training of Medical Professionals-Cross-Sectional Multispecialty Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, L.; Mutter, D.; Pessaux, P.; Marescaux, J. Patient specific anatomy: The new area of anatomy based on computer science illustrated on liver. J. Vis. Surg. 2015, 1, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Lachkar, A.A.; Soler, L.; Diana, M.; Becmeur, F.; Marescaux, J. 3D imaging and urology: Why 3D reconstruction will be mandatory before performing surgery. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2019, 72, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons, American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society. Summary of the Updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

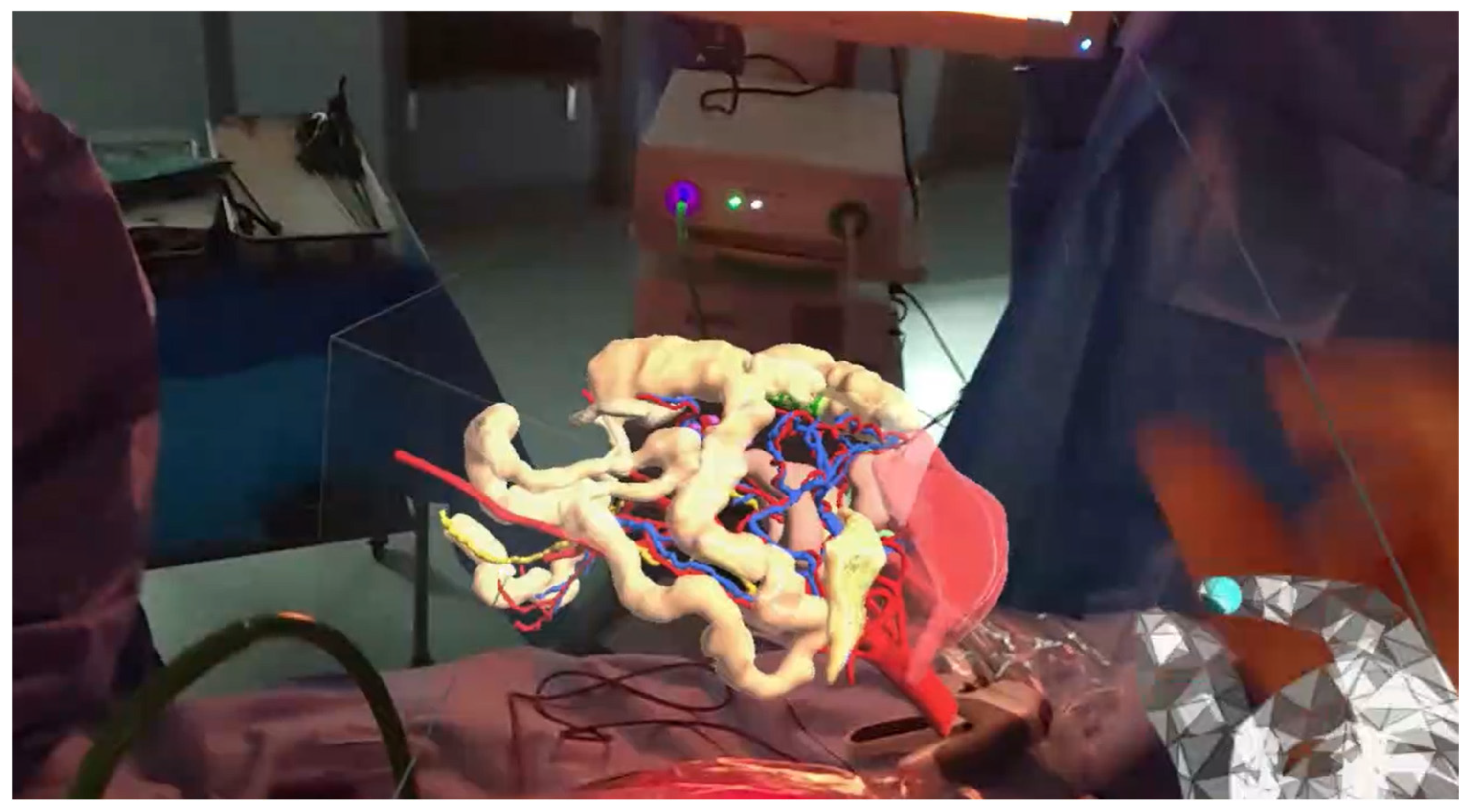

- Moynihan, A.; Khan, M.F.; Cahill, R.A. Intra-operative in-line holographic display of patient-specific anatomy via a three-dimensional virtual model during laparoscopic right hemicolectomy for colon cancer: Video correspondence—A video vignette. Color. Dis. 2023, 25, 2122–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilidis, P.; Edwin, B.; Pelanis, E.; Hidalgo, E.; de’Angelis, N.; Memeo, R.; Aldrighetti, L.; Sutcliffe, R.P. Navigated liver surgery: State of the art and future perspectives. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2022, 21, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singaravelu, A.; Mc Entee, P.D.; Hardy, N.P.; Khan, M.F.; Mulsow, J.; Shields, C.; Cahill, R.A. Clinical evaluation of real-time artificial intelligence provision of expert representation in indocyanine green fluorescence angiography during colorectal resections. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 8246–8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shvets, A.A.; Rakhlin, A.; Kalinin, A.A.; Iglovikov, V.I. Automatic Instrument Segmentation in Robot-Assisted Surgery Using Deep Learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01207. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, A.; Yeung, S.; Jopling, J.; Krause, J.; Azagury, D.; Milstein, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Tool Detection and Operative Skill Assessment in Surgical Videos Using Region-Based Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.W.; Zhao, T.Z.; Schmidgall, S.; Deguet, A.; Kobilarov, M.; Finn, C.; Krieger, A. Surgical robot transformer (srt): Imitation learning for surgical tasks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.12998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piozzi, G.N.; Duhoky, R.; Przedlacka, A.; Ronconi Di Giuseppe, D.; Khan, J.S. Artificial intelligence real-time mapping with Eureka during robotic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: A video vignette. Color. Dis. 2025, 27, e17240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Imaizumi, Y.; Goto, K.; Iwauchi, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Ito, R.; Nakabayashi, Y. Artificial intelligence-enhanced navigation for nerve recognition and surgical education in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg. Endosc. 2025, 39, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrakar, S.; Ratre, R.; Gupta, A.; Agrawal, H.M.; Avinash, R. A study of outcomes in patients undergoing nerve preserving surgery in colorectal cancers. Int. Surg. J. 2022, 10, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, S.; Namazi, B.; Kiani, P.; Hashimoto, D.A.; Alseidi, A.; Pasten, M.; Brunt, L.M.; Gill, S.; Davis, B.; Bloom, M.; et al. Validation of an artificial intelligence platform for the guidance of safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 2260–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.B.; Chen, J.T.; Hansen, P.; Shi, L.X.; Goldenberg, A.; Schmidgall, S.; Scheikl, P.M.; Deguet, A.; White, B.M.; Tsai, R.; et al. SRT-H: A hierarchical framework for autonomous surgery via language-conditioned imitation learning. Sci. Robot. 2025, 10, eadt5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, J.; Takemasa, I.; Kotake, M.; Noura, S.; Kimura, K.; Suwa, H.; Tei, M.; Takano, Y.; Munakata, K.; Matoba, S.; et al. Blood Perfusion Assessment by Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging for Minimally Invasive Rectal Cancer Surgery (EssentiAL trial): A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann. Surg. 2023, 278, e688–e694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isuri, R.K.; Williams, J.; Rioux, D.; Dorval, P.; Chung, W.; Dancer, P.A.; Delikatny, E.J. Clinical Integration of NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging for Cancer Surgery: A Translational Evaluation of Preclinical and Intraoperative Systems. Cancers 2025, 17, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, S.; Babic, B.; Evgeniou, T.; Cohen, I.G. The need for a system view to regulate artificial intelligence/machine learning-based software as medical device. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Hitt, L.M. Beyond computation: Information technology, organizational transformation and business performance. J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. What Is Model Drift? Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/model-drift#:~:text=Model%20drift%20refers%20to%20the,decision%2Dmaking%20and%20bad%20predictions. (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- logz. AI Model Drift. Available online: https://logz.io/glossary/ai-model-drift/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- He, J.; Baxter, S.L.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, K. The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; See, K.C. Artificial Intelligence for COVID-19: Rapid Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Data Protection Supervisor. TechDispatch: Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). 2023. Available online: https://www.edps.europa.eu/system/files/2023-11/23-11-16_techdispatch_xai_en.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “ Why should i trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.I.; Spooner, B.; Isherwood, J.; Lane, M.; Orrock, E.; Dennison, A. A Systematic Review of the Barriers to the Implementation of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Cureus 2023, 15, e46454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill, R.A.; Duffourc, M.; Gerke, S. The AI-enhanced surgeon–Integrating black-box artificial intelligence in the operating room. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 2823–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence and Amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act). 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj/eng (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- U.S. FOOD & DRUG. Administration. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Medical Devices. 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-enabled-medical-devices (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Moynihan, A.; Killeen, D.; Cahill, R.; Singaravelu, A.; Healy, D.; Malone, C.; Mulvany, E.; O’Brien, F.; Ridgway, P.; Ryan, K.; et al. New technologies for future of surgery in Ireland: An RCSI working Group report 2024. Surgeon 2025, 23, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murphy, E.; Cahill, R.A. Technological Advances in Intra-Operative Navigation: Integrating Fluorescence, Extended Reality, and Artificial Intelligence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238574

Murphy E, Cahill RA. Technological Advances in Intra-Operative Navigation: Integrating Fluorescence, Extended Reality, and Artificial Intelligence. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238574

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurphy, Edward, and Ronan A. Cahill. 2025. "Technological Advances in Intra-Operative Navigation: Integrating Fluorescence, Extended Reality, and Artificial Intelligence" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238574

APA StyleMurphy, E., & Cahill, R. A. (2025). Technological Advances in Intra-Operative Navigation: Integrating Fluorescence, Extended Reality, and Artificial Intelligence. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238574