Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome (SLOS)—Case Description and the Impact of Therapeutic Interventions on Psychomotor Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Microcephaly

- Major developmental abnormalities of the central nervous system and/or cortical structure disorders

- Cataracts or microphthalmia

- Cleft uvula/submucous cleft palate/cleft of the hard palate/cleft lip

- Large vessel defects or single-chambered heart

- Hypoplasia or reduced number of lung lobes

- Pyloric stenosis

- Hirschsprung’s disease

- Isolated structural abnormalities or progressive liver dysfunction

- Renal agenesis or clinically significant polycystic kidney disease

- Hypospadias

- Ambiguous or female external genitalia in individuals with 46, XY karyotype

- Underdevelopment of external genitalia in individuals with 46, XX karyotype

- Y-shaped syndactyly of the second and third toes; other syndactylies, polydactylies, and foot deformities [2].

2. Materials and Methods

Multidisciplinary Care

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

- Craniofacial dysmorphisms: slanted palpebral fissures, broad nasal bridge, low-set ears, and a short neck with a cutaneous fold.

- Extremity anomalies: syndactyly of the 2nd and 3rd toes bilaterally, short limbs, and a transverse palmar crease on both hands.

- Other malformations: hemangiomas on the forehead, eyelids, and nose; submucous cleft palate.

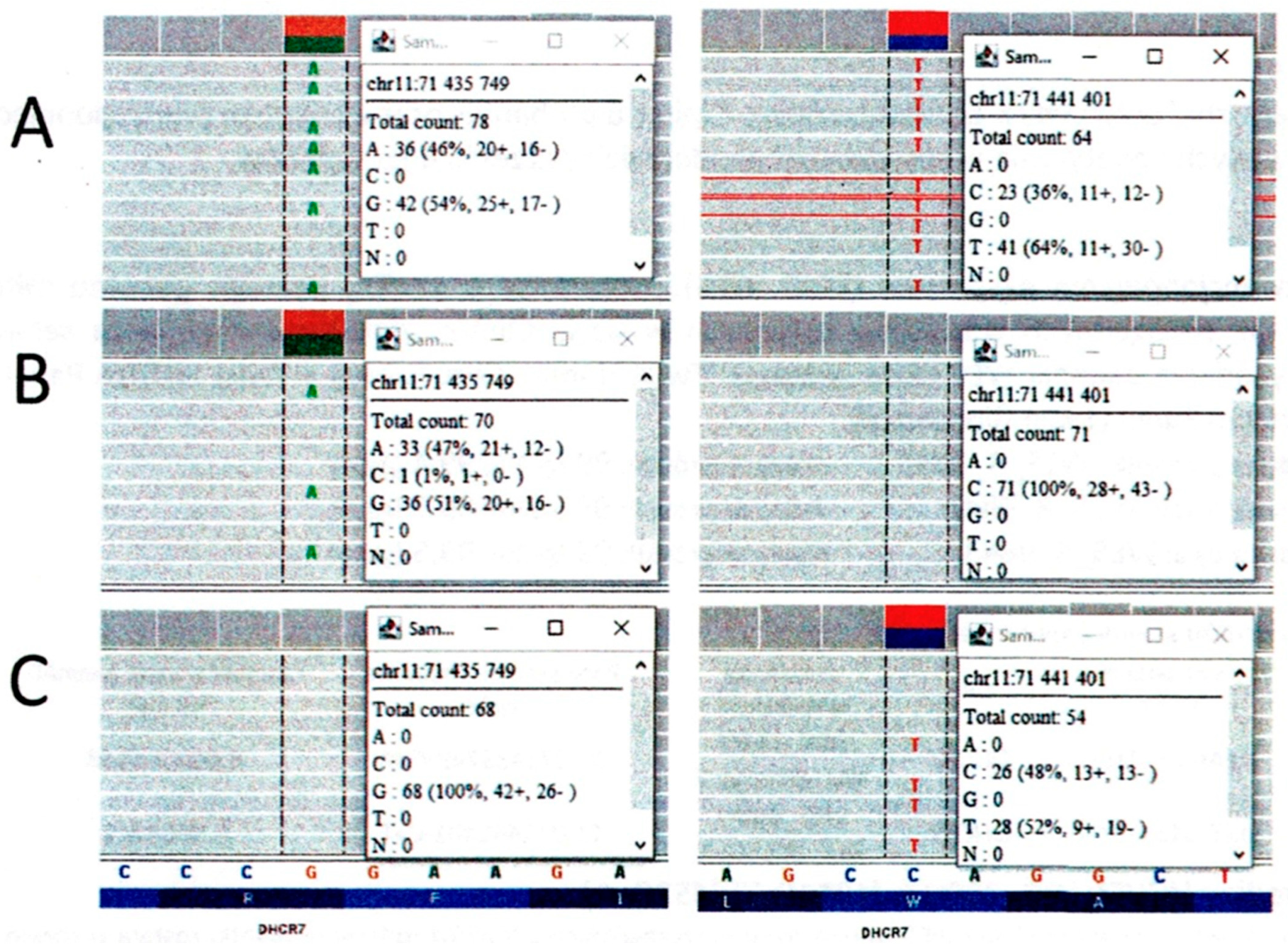

- c.1054C > T (classified as pathogenic; causative of SLOS in an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern).

- c.452G > A (classified as pathogenic/probably pathogenic according to ClinVar, v. 13 July 2021).

3.2. Metabolic Supplementation and Biochemical Monitoring

3.3. Cholesterol and Sterol Precursor Dynamics

3.4. Clinical Course and Interventions

3.5. Early Neurodevelopmental Therapy

3.6. Ongoing Development

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Scientific Interpretation

5.2. Importantly

5.3. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAC | Augmentative and Alternative Communication |

| 7-DHC | 7-dehydrocholesterol |

| 8-DHC | 8-dehydrocholesterol |

| SLOS | Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome |

| WES | Whole Exome Sequencing |

| PEG | Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy |

| tDCS | Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

References

- Smith, D.W.; Lemli, L.; Opitz, J.M. A Newly Recognized Syndrome of Multiple Congenital Anomalies. J. Pediatr. 1964, 64, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langius, F.A.; Waterham, H.R.; Romeijn, G.J.; Oostheim, W.; de Barse, M.M.; Dorland, L.; Duran, M.; Beemer, F.A.; Wanders, R.J.; Poll-The, B.T. Identification of Three Patients with a Very Mild Form of Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2003, 122A, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, J.M.; Penchaszadeh, V.B.; Holt, M.C.; Spano, L.M. Spano Smith-Lemli-Opitz (Rsh) Syndrome Bibliography. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1987, 28, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alley, T.L.; A Gray, B.; Lee, S.H.; Scherer, S.W.; Tsui, L.C.; Tint, G.S.; A Williams, C.; Zori, R.; Wallace, M.R. Identification of a Yeast Artificial Chromosome Clone Spanning a Translocation Breakpoint at 7q32.1 in a Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome Patient. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995, 56, 1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alley, T.L.; Scherer, S.W.; Huizenga, J.J.; Tsui, L.-C.; Wallace, M.R. Physical Mapping of the Chromosome 7 Breakpoint Region in an Slos Patient with T(7;20) (Q32.1;Q13.2). Am. J. Med. Genet. 1997, 31, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.J.; Stephan, M.J.; Walker, W.O.; Kelley, R.I. Variant Rsh/Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome with Atypical Sterol Metabolism. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998, 78, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, H.C.; Frentz, J.; Martinez, J.E.; Tuck-Muller, C.M.; Belliziare, J. Adrenal Insufficiency in Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 82, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, A.V.; Luu, W.; Sharpe, L.J.; Brown, A.J. Cholesterol-Mediated Degradation of 7-Dehydrocholesterol Reductase Switches the Balance from Cholesterol to Vitamin D Synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 8363–8373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DHCR7 7-Dehydrocholesterol Reductase—NIH Genetic Testing Registry (GTR)—NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtr/genes/1717/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Lee, J.N.; Bae, S.-H.; Paik, Y.-K. Structure and Alternative Splicing of the Rat 7-Dehydrocholesterol Reductase Gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1576, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witsch-Baumgartner, M.; Fitzky, B.U.; Ogorelkova, M.; Kraft, H.G.; Moebius, F.F.; Glossmann, H.; Seedorf, U.; Gillessen-Kaesbach, G.; Hoffmann, G.F.; Clayton, P.; et al. Mutational Spectrum in the Delta7-Sterol Reductase Gene and Genotype-Phenotype Correlation in 84 Patients with Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 66, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.L.; Jones, M.C.; Del Campo, M. Atlas of Human Malformation Syndromes by Smith; MediPage: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McMurry, J. Organic Chemistry, 4th ed.; PWN Scientific Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 2000; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Śmigiel, R.; Szczałuba, K. Genetically Determined Developmental Disorders in Children; PWN Scientific Publishers: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, R.I.; Hennekam, R.C. The Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 37, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowaczyk, M.J.; Waye, J.S. The Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome: A Novel Metabolic Way of Understanding Developmental Biology, Embryogenesis, and Dysmorphology. Clin. Genet. 2001, 59, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, F.D. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Management. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 16, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.M.; Tierney, E. Cross-sectional analysis of expressive and receptive language skills in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS). J. Rare Dis. 2025, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, E.; Nwokoro, N.A.; Kelley, R.I. Behavioral Phenotype of Rsh/Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2000, 6, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassif, C.A.; Krakowiak, P.A.; Wright, B.S.; Gewandter, J.S.; Sterner, A.L.; Javitt, N.; Yergey, A.L.; Porter, F.D. Residual Cholesterol Synthesis and Simvastatin Induction of Cholesterol Synthesis in Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome Fibroblasts. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005, 85, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowaczyk, M.J.M.; Wassif, C.A. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. 1998 Nov 13 [Updated 2020 Jan 30]. In GeneReviews® [Internet]; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993–2025. [Google Scholar]

- De Clemente, V.; Vitiello, G.; Imperati, F.; Romano, A.; Parente, I.; Rosa, M.; Pascarella, A.; Parenti, G.; Del Giudice, E. Smith Lemli-Opitz syndrome: A contribution to the delineation of a cognitive/behavioral phenotype. Minerva Pediatr. 2013, 65, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DeBarber, A.E.; Eroglu, Y.; Merkens, L.S.; Pappu, A.S.; Steiner, R.D. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Expert. Rev. Mol. Med. 2011, 13, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurm, A.; Tierney, E.; Farmer, C.; Albert, P.; Joseph, L.; Swedo, S.; Bianconi, S.; Bukelis, I.; Wheeler, C.; Sarphare, G.; et al. Development, Behavior, and Biomarker Characterization of Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome: An Update. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2016, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaub, P.A.; Sharp, P.C.; Ranieri, E.; Fletcher, J.M. Isolated Autism Is. Not. an Indication for Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome Biochemical Testing. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2022, 58, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, E.; Nwokoro, N.A.; Porter, F.D.; Freund, L.S.; Ghuman, J.K.; Kelley, R.I. Behavior phenotype in the RSH/Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 98, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.W.; Yoshida, S.; Jung, E.S.; Mori, S.; Baker, E.H.; Porter, F.D. Corpus callosum measurements correlate with developmental delay in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Pediatr. Neurol. 2013, 49, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sanghera, A.S.; Zeppieri, M. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. [Updated 2024 Jan 11]. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Żukowska, A.; Król, M.; Kupnicka, P.; Bąk, K.; Janawa, K.; Chlubek, D. Exploring Recent Developments in the Manifestation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Patients with Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome: From Molecular Pathways to Clinical Innovations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Irons, M.; Nowaczyk, M. Smith–Lemli–Opitz Syndrome: Phenotype, Natural History, and Epidemiology. Am. J. Med. Genet.-C 2012, 160C, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupe, S.; Hertzog, A.; Foran, C.; Tolun, A.A.; Suthern, M.; Chung, C.W.T.; Ellaway, C. Keeping you on your toes: Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome is an easily missed cause of developmental delays. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gutenbrunner, C.; Schiller, J.; Goedecke, V.; Lemhoefer, C.; Boekel, A. Screening of Patient Impairments in an Outpatient Clinic for Suspected Rare Diseases-A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begic, N.; Begic, Z.; Begic, E. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome: Bosnian and Herzegovinian Experience. Balk. J. Med. Genet. BJMG 2021, 24, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sampling Date | Total Cholesterol | 7-DHC | 8-DHC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23 March 2021 | 17.4 mg/dL (plasma) | 12.089 mg% | 13.650 mg% |

| 18 August 2021 | 48.9 mg/dL (plasma) | 18.546 mg% | 21.086 mg% |

| 26 August 2021 | 77.88 mg/dL (blood) | – | – |

| 27 September 2021 | 65.8 mg/dL (plasma) | 18.812 mg% | 21.123 mg% |

| 15 December 2021 | 96 mg/dL (blood) | – | – |

| 26 January 2022 | 94 mg/dL (blood) | – | – |

| 9 May 2022 | 80.7 mg/dL (plasma); 111 mg/dL (blood) | 20.112 mg% | 24.983 mg% |

| 28 October 2023 | 90 mg/dL (blood) | – | – |

| 31 May 2024 | 103 mg/dL (blood) | – | – |

| 26 March 2025 | 95.2 mg/dL (blood) | – | – |

| Sampling Date | HDL (mg/dL) | Non-HDL (mg/dL) | LDL (mg/dL) | Vitamin D3 (ng/mL) | Triglycerides (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 December 2021 | 31.3 | 64.6 | 43.6 | 51.9 | 105 |

| 26 January 2022 | 27.8 | 83.2 | 67.98 | 101 | 76 |

| 28 October 2023 | 25.0 | 65.0 | 50.0 | 70.2 | 75 |

| 31 May 2024 | 34.1 | 68.9 | 53.58 | 99 | 77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kozera, N.; Śmigiel, R.; Rozensztrauch, A. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome (SLOS)—Case Description and the Impact of Therapeutic Interventions on Psychomotor Development. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8569. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238569

Kozera N, Śmigiel R, Rozensztrauch A. Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome (SLOS)—Case Description and the Impact of Therapeutic Interventions on Psychomotor Development. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8569. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238569

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozera, Natalia, Robert Śmigiel, and Anna Rozensztrauch. 2025. "Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome (SLOS)—Case Description and the Impact of Therapeutic Interventions on Psychomotor Development" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8569. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238569

APA StyleKozera, N., Śmigiel, R., & Rozensztrauch, A. (2025). Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome (SLOS)—Case Description and the Impact of Therapeutic Interventions on Psychomotor Development. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8569. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238569