Determinants of Length of Hospital Stay in Older Adult Hip Fracture Patients in a Northern Peruvian Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

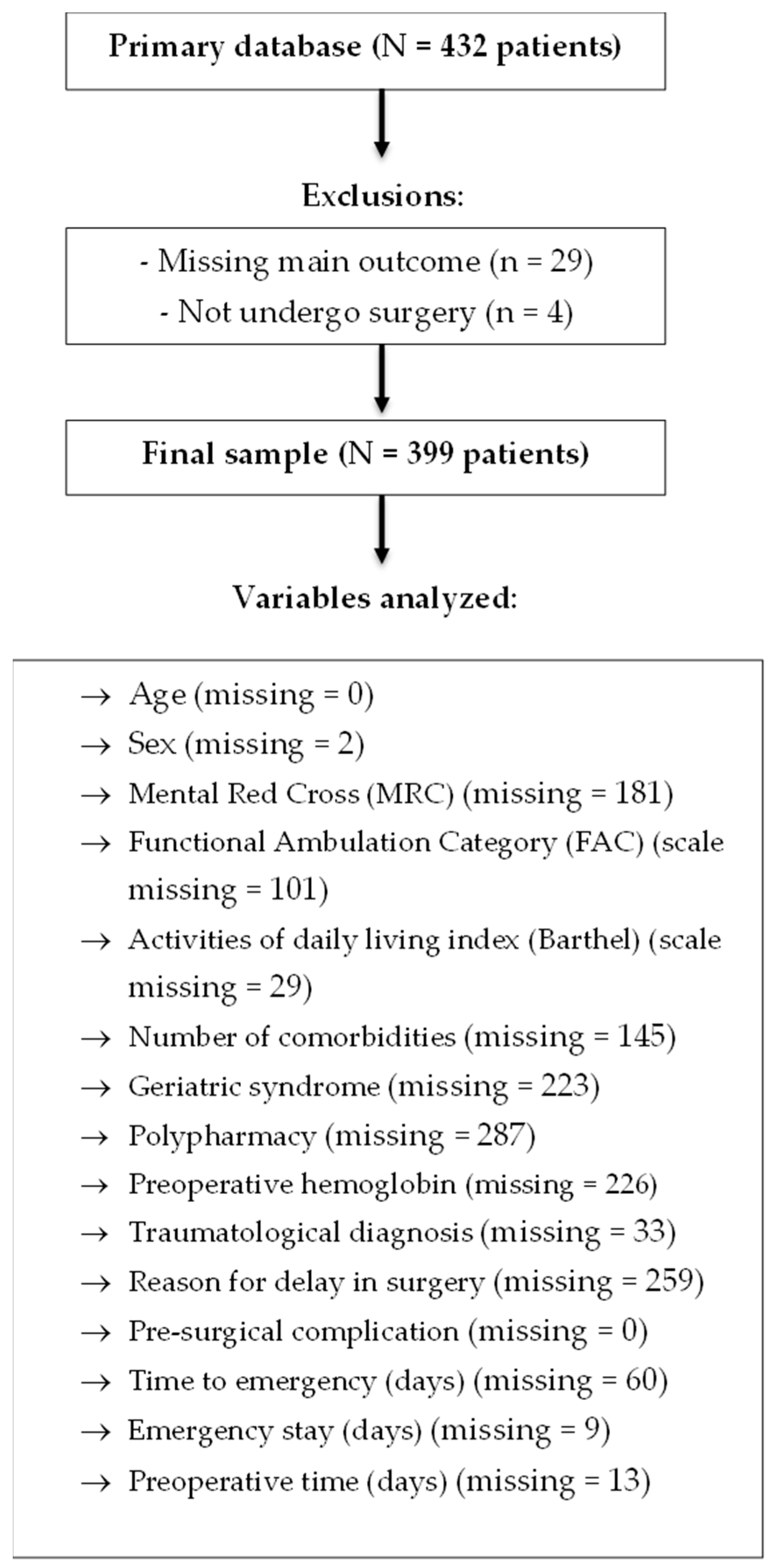

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population, Sample, and Sampling

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Variables

2.5. Procedures and Techniques

2.6. Data Analysis Plan

2.7. Ethical Considerations

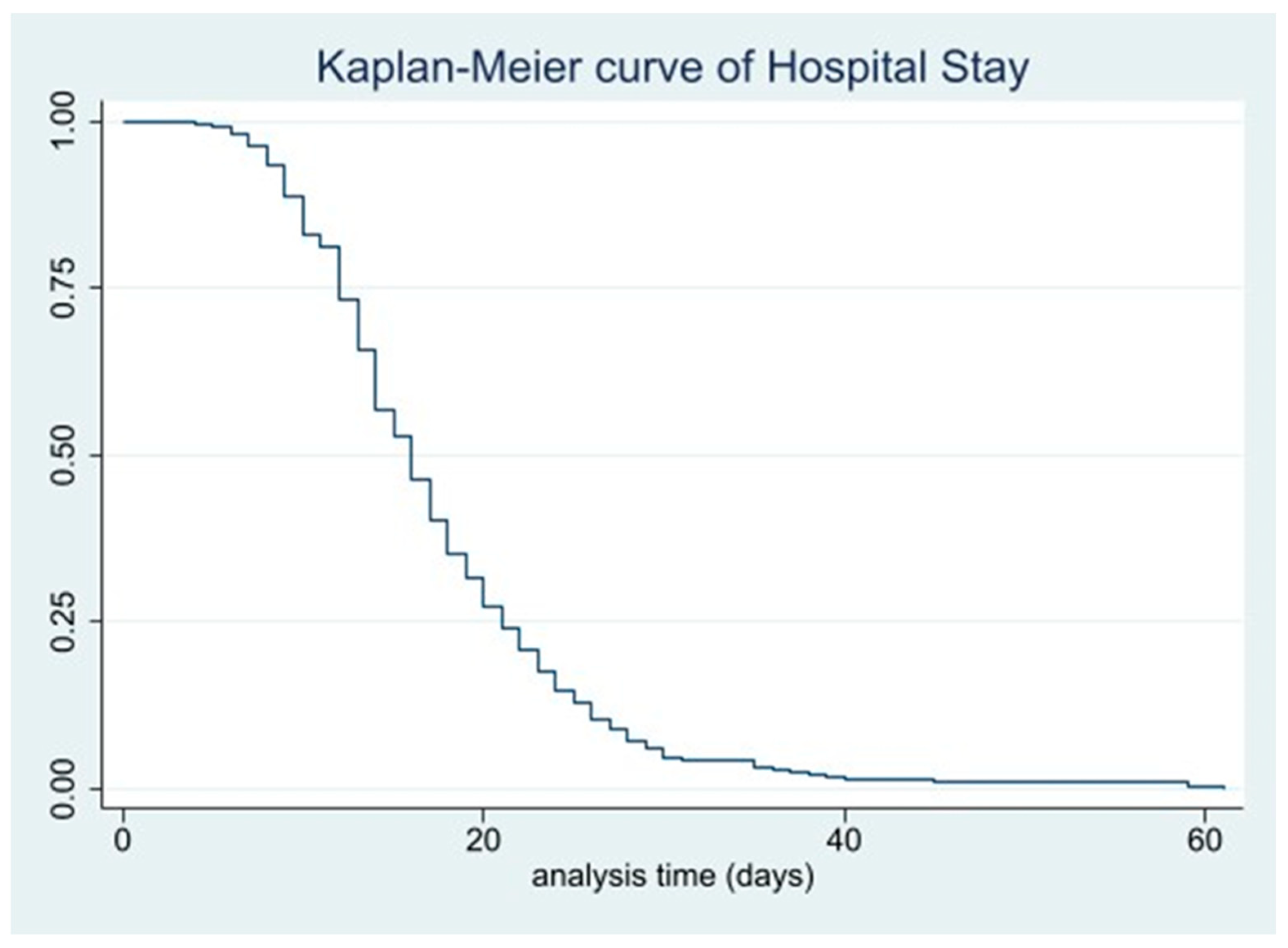

3. Results

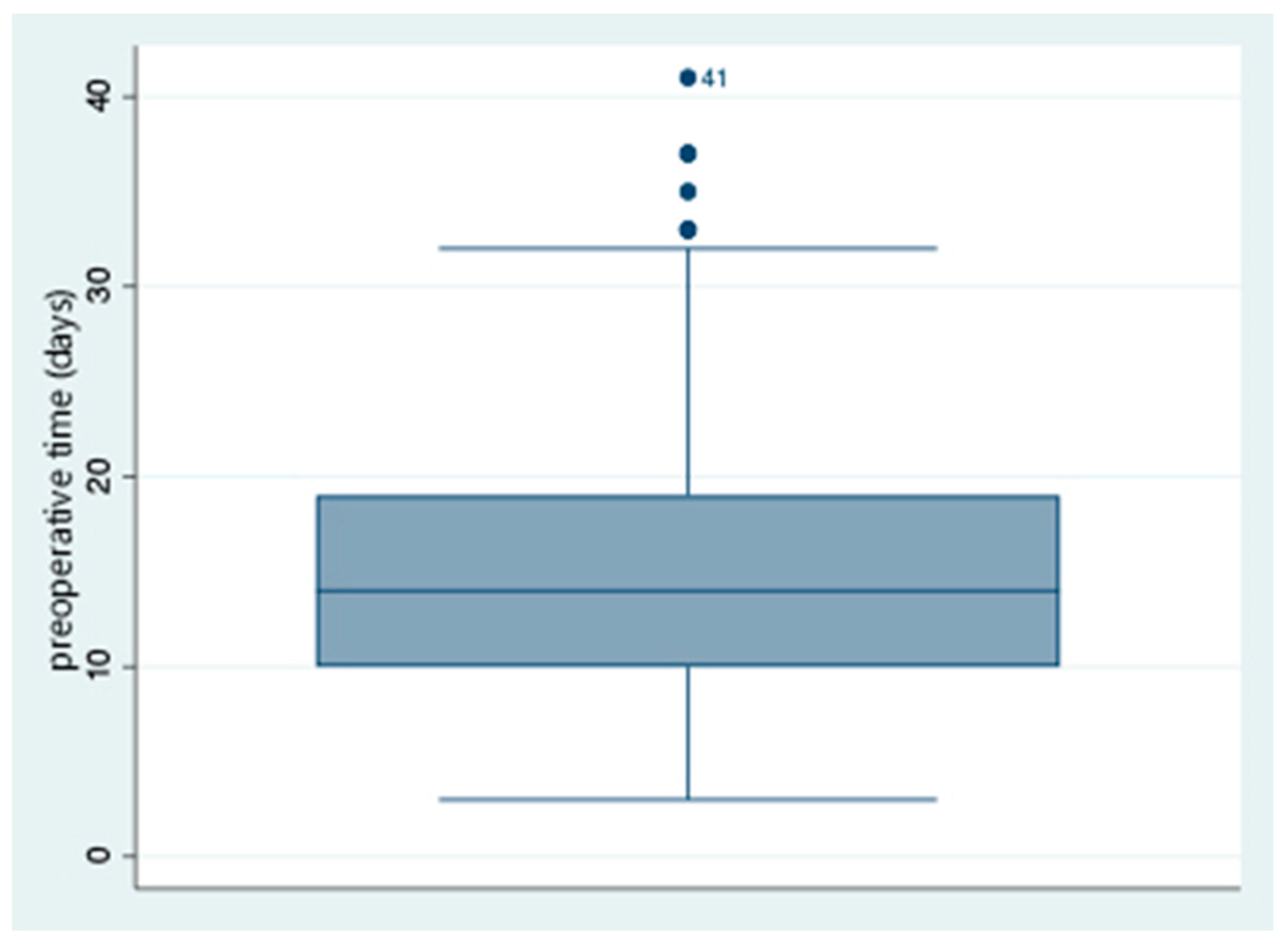

3.1. Epidemiological Characteristics and Hospitalization Times of the Population

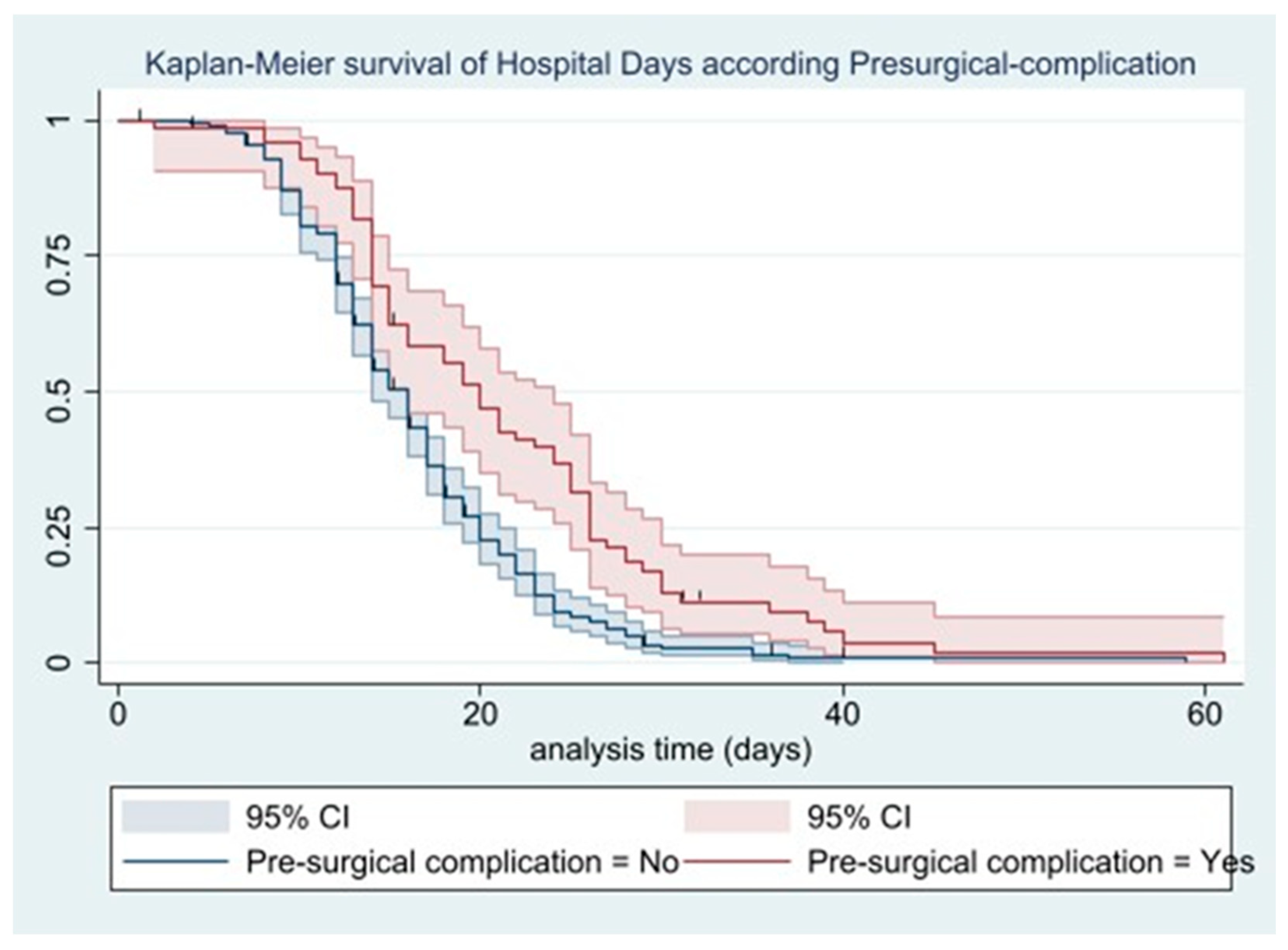

3.2. Simple Poisson Regression Analysis

3.3. Adjusted Model Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Average Hospital Stays of Older Adult Hip Fracture Patients

4.2. Dementia and Length of Hospital Stay

4.3. Preoperative Complications and Length of Hospital Stay

4.4. Hospital Times and Length of Hospital Stay

4.5. Other Determinants of Hospital Stay

4.6. Practical Implications of Findings in Geriatrics

4.7. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dyer, S.M.; Crotty, M.; Fairhall, N.; Magaziner, J.; Beaupre, L.A.; Cameron, I.D.; Sherrington, C.; Fragility Fracture Network (FFN) Rehabilitation Research Special Interest Group. A Critical Review of the Long-Term Disability Outcomes Following Hip Fracture. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino, L.; Ramírez, R.; Vejarano, J.; Ticse, R. Fractura de Cadera En El Adulto Mayor: La Epidemia Ignorada En El Perú. Acta Médica Peru. 2016, 33, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, B.; van der Kaaij, M.; Nelissen, R.; van Wijnen, J.-K.; Drost, K.; Blauw, G.J. Prevention of Hip Fractures in Older Adults Residing in Long-Term Care Facilities with a Hip Airbag: A Retrospective Pilot Study. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Xiao, Z.; Sun, C.; Xu, G.; He, J. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Hip Fractures From 1990 to 2021: Results from Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, C.-W.; Lin, T.-C.; Bartholomew, S.; Bell, J.S.; Bennett, C.; Beyene, K.; Bosco-Levy, P.; Bradbury, B.D.; Chan, A.H.Y.; Chandran, M.; et al. Global Epidemiology of Hip Fractures: Secular Trends in Incidence Rate, Post-Fracture Treatment, and All-Cause Mortality. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2023, 38, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, K.; Kang, H.; Ye, D.; Li, F. What Was the Epidemiology and Global Burden of Disease of Hip Fractures From 1990 to 2019? Results From and Additional Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Clin. Orthop. 2023, 481, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, F.; Moldovan, L. A Modeling Study for Hip Fracture Rates in Romania. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musculoskeletal Conditions Affect Millions. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-10-2003-musculoskeletal-conditions-affect-millions (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Lari, A.; Haidar, A.; AlRumaidhi, Y.; Awad, M.; AlMutairi, O. Predictors of Mortality and Length of Stay after Hip Fractures––A Multicenter Retrospective Analysis. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2022, 28, 101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLellan, C.; Faig, K.; Cooper, L.; Benjamin, S.; Shanks, J.; Flewelling, A.J.; Dutton, D.J.; McGibbon, C.; Bohnsack, A.; Wagg, J.; et al. Health Outcomes of Older Adults after a Hospitalization for a Hip Fracture. Can. Geriatr. J. 2024, 27, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.I.; Switzer, J.A. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline Summary: Management of Hip Fractures in Older Adults. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 30, e1291–e1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Flores, J.O.; Cortez-Sarabia, J.A.; Sánchez-García, S.; Medina-Chávez, J.H.; Castro-Flores, S.G.; Borboa-García, C.A.; Luján-Hernández, I.; López-Hernández, G.G. First Year Report of the IMSS Multicenter Hip Fracture Registry. Arch. Osteoporos. 2024, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auais, M.; Al-Zoubi, F.; Matheson, A.; Brown, K.; Magaziner, J.; French, S.D. Understanding the Role of Social Factors in Recovery after Hip Fractures: A Structured Scoping Review. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweller, E.; Mueller, J.; Rivera, O.J.; Villegas, S.J.; Walkiewicz, J. Factors Associated with Hip Fracture Length of Stay Among Older Adults in a Community Hospital Setting. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. Glob. Res. Rev. 2023, 7, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klestil, T.; Röder, C.; Stotter, C.; Winkler, B.; Nehrer, S.; Lutz, M.; Klerings, I.; Wagner, G.; Gartlehner, G.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B. Impact of Timing of Surgery in Elderly Hip Fracture Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leer-Salvesen, S.; Engesæter, L.B.; Dybvik, E.; Furnes, O.; Kristensen, T.B.; Gjertsen, J.-E. Does Time from Fracture to Surgery Affect Mortality and Intraoperative Medical Complications for Hip Fracture Patients? An Observational Study of 73 557 Patients Reported to the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register. Bone Jt. J. 2019, 101-B, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polisetty, T.S.; Jain, S.; Pang, M.; Karnuta, J.M.; Vigdorchik, J.M.; Nawabi, D.H.; Wyles, C.C.; Ramkumar, P.N. Concerns Surrounding Application of Artificial Intelligence in Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Review of Literature and Recommendations for Meaningful Adoption. Bone Jt. J. 2022, 104-B, 1292–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, T.; Försth, P.; Skorpil, M.; Pazarlis, K.; Öhagen, P.; Michaëlsson, K.; Sandén, B. Decompression Alone or Decompression with Fusion for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial with Two-Year MRI Follow-Up. Bone Jt. J. 2022, 104-B, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Maggi, S. Epidemiology and Social Costs of Hip Fracture. Injury 2018, 49, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vento-Benel, R.F.; Salinas-Salas, C.; De la Cruz-Vargas, J.A. Factores Pronósticos Asociados a Mala Evolución En Pacientes Operados de Fractura de Cadera Mayores de 65 Años. Rev. Fac. Med. Humana 2019, 19, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E. Hip Fractures: Mortality, Economic Burden, and Organisational Factors for Improved Patient Outcomes. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023, 4, e360–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.; Baker, G.; MacDonald, J.; Thompson, N.W. Co-Morbidities in Patients with a Hip Fracture. Ulster Med. J. 2019, 88, 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.H.; Kim, B.R.; Lee, S.Y.; Beom, J.; Choi, J.H.; Lim, J.-Y. Influence of Comorbidities on Functional Outcomes in Patients with Surgically Treated Fragility Hip Fractures: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Lu, H.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, B. Comorbidities as Predictors of Inpatient Deaths after Hip Fracture in Chinese Elderly Patients: Analysis of Hospital Records. Lancet 2017, 390, S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, S.; Lavanderos, J.; Vilches, L.; Delgado, M.; Cárcamo, K.; Passalaqua, S.; Guarda, M. Fractura de Cadera. Cuad. Cir. 2008, 22, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpintero, P.; Caeiro, J.R.; Carpintero, R.; Morales, A.; Silva, S.; Mesa, M. Complications of Hip Fractures: A Review. World J. Orthop. 2014, 5, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, T.; Bei, D.-K.; Wang, Q. Relationship between Admission Blood Urea Nitrogen Levels and Postoperative Length of Stay in Patients with Hip Fracture: A Retrospective Study. Medicine 2024, 103, e38918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkel, L.E.; Kates, S.L.; Schreck, M.; Maceroli, M.; Mahmood, B.; Elfar, J.C. Length of Hospital Stay after Hip Fracture and Risk of Early Mortality after Discharge in New York State: Retrospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2015, 351, h6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, A.G.; Ambler, G.; Barber, J.A. Sample Size Calculations Based on a Difference in Medians for Positively Skewed Outcomes in Health Care Studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017, 17, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marufu, T.C.; Elphick, H.L.; Ahmed, F.B.; Moppett, I.K. Short-Term Morbidity Factors Associated with Length of Hospital Stay (LOS): Development and Validation of a Hip Fracture Specific Postoperative Morbidity Survey (HF-POMS). Injury 2019, 50, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abizanda Soler, P.; Gallego Moreno, J.; Sánchez Jurado, P.; Díaz Torres, C. Instrumentos de Valoración Geriátrica Integral en los servicios de Geriatría de España: Uso heterogéneo de nuestra principal herramienta de trabajo. Rev. Esp. Geriatría Gerontol. 2000, 35, 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Koo, C.J.; Fernández-Mogollón, J.; Hirakata Nakayama, C.; Díaz-Koo, C.J.; Fernández-Mogollón, J.; Hirakata Nakayama, C. Características de Los Pacientes Con Estancia Prolongada En El Servicio de Cirugía General Del Hospital Nacional Almanzor Aguinaga Asenjo. Rev. Cuerpo Méd. Hosp. Nac. Almanzor Aguinaga Asenjo 2020, 13, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Qian, H.; Ye, J.; Qian, J.; Hua, J. Correlation between Common Postoperative Complications of Prolonged Bed Rest and Quality of Life in Hospitalized Elderly Hip Fracture Patients. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizkalla, J.M.; Nimmons, S.J.B.; Helal, A.; Prajapati, P.; Jones, A.L. Relation of Mobilization After Hip Fractures on Day of Surgery to Length of Stay. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2022, 35, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monacelli, F.; Pizzonia, M.; Signori, A.; Nencioni, A.; Giannotti, C.; Minaglia, C.; Granello di Casaleto, T.; Podestà, S.; Santolini, F.; Odetti, P. The In-Hospital Length of Stay after Hip Fracture in Octogenarians: Do Delirium and Dementia Shape a New Care Process? J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 66, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, B.; Guy, P.; Sheehan, K.J.; Kuramoto, L.; Bohm, E.; Beaupre, L.; Sutherland, J.M.; Dunbar, M.; Griesdale, D.; Morin, S.N.; et al. Time Trends in Hospital Stay after Hip Fracture in Canada, 2004–2012: Database Study. Arch. Osteoporos. 2016, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Granados, D.; Rangel-Rivera, K.; Osma-Hurtado, J.; Márquez-Bayona, K.; Romero-Marín, M.; Cadena-Sanabria, M.O. Desenlaces adversos perioperatorios en ancianos con fractura de cadera, antes y después de la implementación de un protocolo de ortogeriatría. Rev. Colomb. Ortop. Traumatol. 2023, 37, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja-Sobrón, F.D.; Alonso-Polo, B.; Borja-Sobrón, F.D.; Alonso-Polo, B. Implementación de un proceso clínico integrado para la atención de la fractura de cadera en pacientes mayores de 65 años. Acta Ortopédica Mex. 2018, 32, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcheix, P.-S.; Collin, C.; Hardy, J.; Mabit, C.; Tchalla, A.; Charissoux, J.-L. Impact of Orthogeriatric Management on the Average Length of Stay of Patients Aged over Seventy Five Years Admitted to Hospital after Hip Fractures. Int. Orthop. 2021, 45, 1431–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasu, R.S.; Zalmai, R.; Karpes Matusevich, A.R.; Hunt, S.L.; Phadnis, M.A.; Rianon, N. Shorter Length of Hospital Stay for Hip Fracture in Those with Dementia and without a Known Diagnosis of Osteoporosis in the USA. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristan, A.; Omahen, S.; Tosounidis, T.H.; Cimerman, M. When Does Hip Fracture Surgery Delay Affects the Length of Hospital Stay? Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. Off. Publ. Eur. Trauma Soc. 2022, 48, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, H.; Kazui, H.; Shigenobu, K.; Masaki, Y.; Hatta, N.; Yamamoto, D.; Wada, T.; Nomura, K.; Yoshiyama, K.; Tabushi, K.; et al. Predictors of Prolonged Hospital Stay for the Treatment of Severe Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Patients with Dementia: A Cohort Study in Multiple Hospitals. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möllers, T.; Stocker, H.; Wei, W.; Perna, L.; Brenner, H. Length of Hospital Stay and Dementia: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duah-Owusu White, M.; Vassallo, M.; Kelly, F.; Nyman, S. Two Factors That Can Increase the Length of Hospital Stay of Patients with Dementia. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2022, 57, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, B.; Sun, W.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Wang, G.; Dou, Q. Prognostic Significance of Frailty in Older Patients with Hip Fracture: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Orthop. 2022, 46, 2939–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kistler, E.A.; Nicholas, J.A.; Kates, S.L.; Friedman, S.M. Frailty and Short-Term Outcomes in Patients with Hip Fracture. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2015, 6, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfold, R.S.; Hall, A.J.; Anand, A.; Clement, N.D.; Duckworth, A.D.; MacLullich, A.M.J. Delirium in Hip Fracture Patients Admitted from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic Is Associated with Higher Mortality, Longer Total Length of Stay, Need for Post-Acute Inpatient Rehabilitation, and Readmission to Acute Services. Bone Jt. Open 2023, 4, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntuli, M.; Filmalter, C.J.; White, Z.; Heyns, T. Length of Stay and Contributing Factors in Elderly Patients Who Have Undergone Hip Fracture Surgery in a Tertiary Hospital in South Africa. Int. J. Orthop. Trauma Nurs. 2020, 37, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Lyu, H.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Fu, X.; Wu, H.; Wu, R.; Yin, P.; Zhang, L.; et al. Trends in Comorbidities and Postoperative Complications of Geriatric Hip Fracture Patients from 2000 to 2019: Results from a Hip Fracture Cohort in a Tertiary Hospital. Orthop. Surg. 2021, 13, 1890–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, P.; Fuentes, P.; Diaz, A.; Martinez, F.; Amenabar, P.; Schweitzer, D.; Botello, E.; Gac, H. Comparison of Complications and Length of Hospital Stay between Orthopedic and Orthogeriatric Treatment in Elderly Patients with a Hip Fracture. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2012, 3, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. Overview Guidance. Hip Fracture: Management. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg124 (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Zemni, I.; Meriem, K.; Khelil, M.; Safer, M.; Zoghlami, C.; Ben Abdelaziz, A. Quality Indicators of Hip Fracture Management. A Systematic Review. Tunis. Med. 2020, 98, 913–925. [Google Scholar]

- Varady, N.H.; Ameen, B.T.; Chen, A.F. Is Delayed Time to Surgery Associated with Increased Short-Term Complications in Patients with Pathologic Hip Fractures? Clin. Orthop. 2020, 478, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heghe, A.; Mordant, G.; Dupont, J.; Dejaeger, M.; Laurent, M.R.; Gielen, E. Effects of Orthogeriatric Care Models on Outcomes of Hip Fracture Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2022, 110, 162–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.Y.; Shanahan, E.; Butler, A.; Lenehan, B.; O’Connor, M.; Lyons, D.; Ryan, J.P. Dedicated Orthogeriatric Service Reduces Hip Fracture Mortality. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 186, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazona-Santabalbina, F.J.; Ojeda-Thies, C.; Figueroa Rodríguez, J.; Cassinello-Ogea, C.; Caeiro, J.R. Orthogeriatric Management: Improvements in Outcomes during Hospital Admission Due to Hip Fracture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J. Big Data-Driven Determinants of Length of Stay for Patients with Hip Fracture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.A.; Wilson, J.L.; Schaffer, N.E.; Olsen, E.C.; Perdue, A.; Ahn, J.; Hake, M.E. Preoperative Comorbidities Associated with Early Mortality in Hip Fracture Patients: A Multicenter Study. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2023, 31, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.M.; Denyer, S.; Brown, N.M. Risk Factors Associated With Extended Length of Hospital Stay After Geriatric Hip Fracture. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. Glob. Res. Rev. 2021, 5, e21.00073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD): 15 Years of Quality Improvement. Available online: https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/nhfd-sep23/ (accessed on 27 July 2024).

- Aguirre-Milachay, E.; León-Figueroa, D.A.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J. Clinical, Laboratory, and Hospital Factors Associated with Preoperative Complications in Peruvian Older Adults with Hip Fracture. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, M.; Marc, C.; Talha, A.; Ruiz, N.; Noublanche, S.; Gillibert, A.; Bergman, S.; Rony, L.; Maynard, V.; Hubert, L. Fast Track Care for Pertrochanteric Hip Fractures: How Does It Impact Length of Stay and Complications? Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2019, 105, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Zeng, L.; Li, S.; Luo, F.; Xiang, Z.; Ding, Q. Relationship between Comorbidities and Treatment Decision-Making in Elderly Hip Fracture Patients. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 31, 1735–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, D.; Ren, S.; Gao, Y.; Sun, W.; Yang, S. Relationship between Preoperative Hemoglobin Levels and Length of Stay in Elderly Patients with Hip Fractures: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicine 2024, 103, e38518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fluck, D.; Lisk, R.; Yeong, K.; Robin, J.; Fry, C.H.; Han, T.S. Association of Polypharmacy and Anticholinergic Burden with Length of Stay in Hospital Amongst Older Adults Admitted with Hip Fractures: A Retrospective Observational Study. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2023, 112, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total N = 399 | Prolonged Hospital Stay | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Age | 82.25 ± 8.18 | 81.99 ± 8.23 | 85.54 ± 6.86 |

| Sex ⁂ | |||

| Male | 144 (36.3) | 131 (35.6) | 13 (44.8) |

| Female | 253 (63.7) | 237 (64.4) | 16 (55.2) |

| Mental Red Cross (MRC) ⁂ | |||

| Normal | 70/218 (32.1) | 66 (32.4) | 4 (28.6) |

| Some memory disorder | 52/218 (23.9) | 49 (24) | 3 (21.4) |

| Memory and orientation impairment | 50/218 (22.9) | 47 (23) | 3 (21.4) |

| Severe memory and orientation impairment | 37/218 (17) | 34 (16.7) | 3 (21.4) |

| Dementia and incontinence | 8/218 (3.7) | 7 (3.4) | 1 (7.1) |

| Advanced dementia | 1/218 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| Functional Ambulation Category (FAC) scale ⁂ | |||

| Walks with extensive assistance from 1 person | 34/298 (11.4) | 29 (10.5) | 5 (21.7) |

| Walks with light physical contact | 47/298 (15.7) | 44 (15.9) | 3 (13) |

| Walks with supervision | 55/298 (18.4) | 50 (18.1) | 5 (21.7) |

| Independent ambulation on level ground | 52/298 (17.4) | 48 (17.4) | 4 (17.4) |

| Walks independently on level ground and up stairs | 51/298 (17.1) | 49 (17.8) | 2 (8.7) |

| Normal ambulation | 59/298 (20.1) | 53 (20.1) | 6 (17.1) |

| Activities of daily living index (Barthel) ⁂ | 80.36 ± 23.22 | 80.96 ± 22.62 | 72.50 ± 29.47 |

| Polypharmacy ⁂ | |||

| No | 9/112 (8) | 8 (7.5) | 1 (16.7) |

| Yes | 103/112 (92) | 98 (92.5) | 5 (83.3) |

| Geriatric syndrome ⁂ | 3.36 ± 2.47 | 3.41 ± 2.5 | 2.67 ± 1.92 |

| Dementia or cognitive impairment | 32/61 (52.5) | 29 (50.9) | 3 (75) |

| Visual deprivation | 9/61 (14.8) | 9 (15.8) | 0 (0) |

| Falls | 8/61 (13.1) | 8 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Depression | 12/61 (19.7) | 11 (19.3) | 1 (25) |

| Comorbidities | 1.81 ± 1.26 | 1.8 ± 1.26 | 1.92 ± 1.26 |

| Diabetes | 15/163 (9.32) | 14 (9.03) | 1 (14.29) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 59/163 (36.65) | 57 (36.77) | 2 (28.57) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 5/163 (3.11) | 5 (3.87) | 0 |

| Osteoarticular disease | 15/163 (9.32) | 14 (9.03) | 1 (14.29) |

| Neurological disease | 12/163 (7.45) | 12 (7.74) | 0 |

| Laboratory analysis | |||

| Preoperative hemoglobin | 10.99 ± 1.91 | 11.1 ± 1.88 | 10.2 ± 2.03 |

| Traumatological diagnosis | |||

| Neck fracture | 108/366 (29.5) | 103 (30.2) | 5 (20) |

| ITT Fracture I–II | 97/366 (26.8) | 86 (25.2) | 11 (44) |

| ITT Fracture III–IV | 120/366 (32.5) | 114 (33.4) | 6 (24) |

| Subtrochanteric fracture | 41/366 (11.2) | 38 (11.1) | 3 (12) |

| Reason for delay in surgery | |||

| Scheduling | 76140 (54.3) | 71 (54.2) | 5 (55.6) |

| Waiting for a hospitalization bed | 45/140 (32.1) | 42 (32.1) | 3 (33.3) |

| Surgical material | 8/140 (5.7) | 8 (6.1) | 0 |

| Medical complication | 11/140 (7.9) | 10 (7.6) | 1 (11.1) |

| Pre-surgical complication | |||

| No | 326 (77.08) | 301 (81.4) | 25 (86.2) |

| Yes | 73 (22.9) | 69 (18.6) | 4 (13.8) |

| Variable | Total N = 399 | Prolonged Hospital Stay | p-Value ** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Time to emergency (days) | 1 * (1-0) | 1 * (2-0) | 0.5 * (1-0) | 0.408 |

| Emergency stay (days) | 3 * (5-2) | 3 * (5-2) | 3 * (5-1) | <0.001 |

| Pre-operative time (days) | 14 * (19-10) | 14 * (19-11) | 6 * (7-5) | <0.001 |

| Characteristics | Hospital Stay (HS) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR Crude | p-Value | IRR Adjusted (Model 1) | p-Value * | IRR Adjusted (Model 2) | p-Value * | IRR Adjusted (Model 3) | p-Value * | |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.024 | - | - | ||||

| Sex ⁂ | ||||||||

| Male | Ref. | |||||||

| Female | 1.06 | 0.009 | 1.04 | 0.508 | 1.04 | 0.508 | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Number of comorbidities | 1.07 | <0.001 | - | |||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.92 | 0.457 | - | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.92 | 0.303 | - | |||||

| Multimorbidity ** | 1.21 | <0.001 | 1.14 | 0.110 | 1.14 | 0.110 | ||

| Mental Red Cross (MRC) scale ⁂ | 0.021 | |||||||

| Normal | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Some memory disorders | 1.17 | <0.001 | 1.16 | 0.058 | 1.16 | 0.058 | ||

| Memory and orientation impairment | 1.08 | 0.068 | 0.95 | 0.604 | 0.95 | 0.604 | ||

| Severe memory and orientation impairment | 1.12 | 0.019 | 1.06 | 0.504 | 1.06 | 0.504 | ||

| Dementia and incontinence | 1.09 | 0.336 | 0.76 | 0.128 | 0.76 | 0.128 | ||

| Advanced dementia | 2.46 | <0.001 | 1.82 (1.03–3.23) | 0.04 | 1.82 (1.02–3.23) | 0.04 | ||

| Activities of Daily Living Index (Barthel) ⁂ | 0.99 | 0.005 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Functional Ambulation Category (FAC) scale ⁂ | <0.001 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Walks with extensive assistance from 1 person | 1.28 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Walks with light physical contact | 1.26 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Walks with supervision | 1.35 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Independent ambulation on level ground | 1.28 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Walks independently on level ground and up stairs | 1.19 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Geriatric syndrome ⁂ | ||||||||

| Number of geriatric syndromes | 1.05 | <0.001 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Dementia | - | - | - | |||||

| Visual deprivation | 1.09 | 0.396 | - | - | - | |||

| Falls | 1.19 | 0.079 | - | - | - | |||

| Depression | 1.09 | 0.314 | - | - | - | |||

| Laboratory analysis | ||||||||

| Preoperative hemoglobin | 0.99 | 0.837 | ||||||

| Trauma diagnosis | 0.006 | |||||||

| Cervical fracture | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| ITT fracture I and II | 0.99 | 0.858 | 1.07 | 0.333 | 1.08 | 0.333 | ||

| ITT fracture III and IV | 1.07 | 0.035 | 1.09 | 0.275 | 1.08 | 0.275 | ||

| Subtrochanteric fracture | 1.12 | 0.006 | 1.2 | 0.120 | 1.2 | 0.120 | ||

| Reason for delay in surgery | <0.001 | |||||||

| Medical complication | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Waiting for a hospital bed | 0.87 | 0.004 | 0.94 | 0.384 | 0.94 | 0.333 | ||

| Lack of surgical material | 1.19 | 0.036 | 1.06 | 0.719 | 1.05 | 0.275 | ||

| Delayed surgical scheduling | 1.21 | 0.006 | 0.81 | 0.108 | 0.81 | 0.120 | ||

| Pre-surgical complication | 1.30 | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.30–1.86) | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.30–1.86) | <0.001 | ||

| Time to emergency (days) | 1.00 | 0.14 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Emergency stay (days) | 1.03 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 0.257 | - | - | ||

| Pre-operative time (days) | 1.05 | <0.001 | 7.44 (6.96–7.96) | <0.001 | - | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aguirre-Milachay, E.; Sarmiento Llaguenta, B.W.; Verona Mendoza, J.M.; León-Figueroa, D.A.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J. Determinants of Length of Hospital Stay in Older Adult Hip Fracture Patients in a Northern Peruvian Hospital. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8564. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238564

Aguirre-Milachay E, Sarmiento Llaguenta BW, Verona Mendoza JM, León-Figueroa DA, Valladares-Garrido MJ. Determinants of Length of Hospital Stay in Older Adult Hip Fracture Patients in a Northern Peruvian Hospital. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8564. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238564

Chicago/Turabian StyleAguirre-Milachay, Edwin, Bryam William Sarmiento Llaguenta, Jesús Manuel Verona Mendoza, Darwin A. León-Figueroa, and Mario J. Valladares-Garrido. 2025. "Determinants of Length of Hospital Stay in Older Adult Hip Fracture Patients in a Northern Peruvian Hospital" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8564. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238564

APA StyleAguirre-Milachay, E., Sarmiento Llaguenta, B. W., Verona Mendoza, J. M., León-Figueroa, D. A., & Valladares-Garrido, M. J. (2025). Determinants of Length of Hospital Stay in Older Adult Hip Fracture Patients in a Northern Peruvian Hospital. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8564. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238564