When Blood Disorders Meet Cancer: Uncovering the Oncogenic Landscape of Sickle Cell Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiological Studies of Cancer Risk in Sickle Cell Disease

3. Clinical Features of Leukemia Reported in Sickle Cell Disease

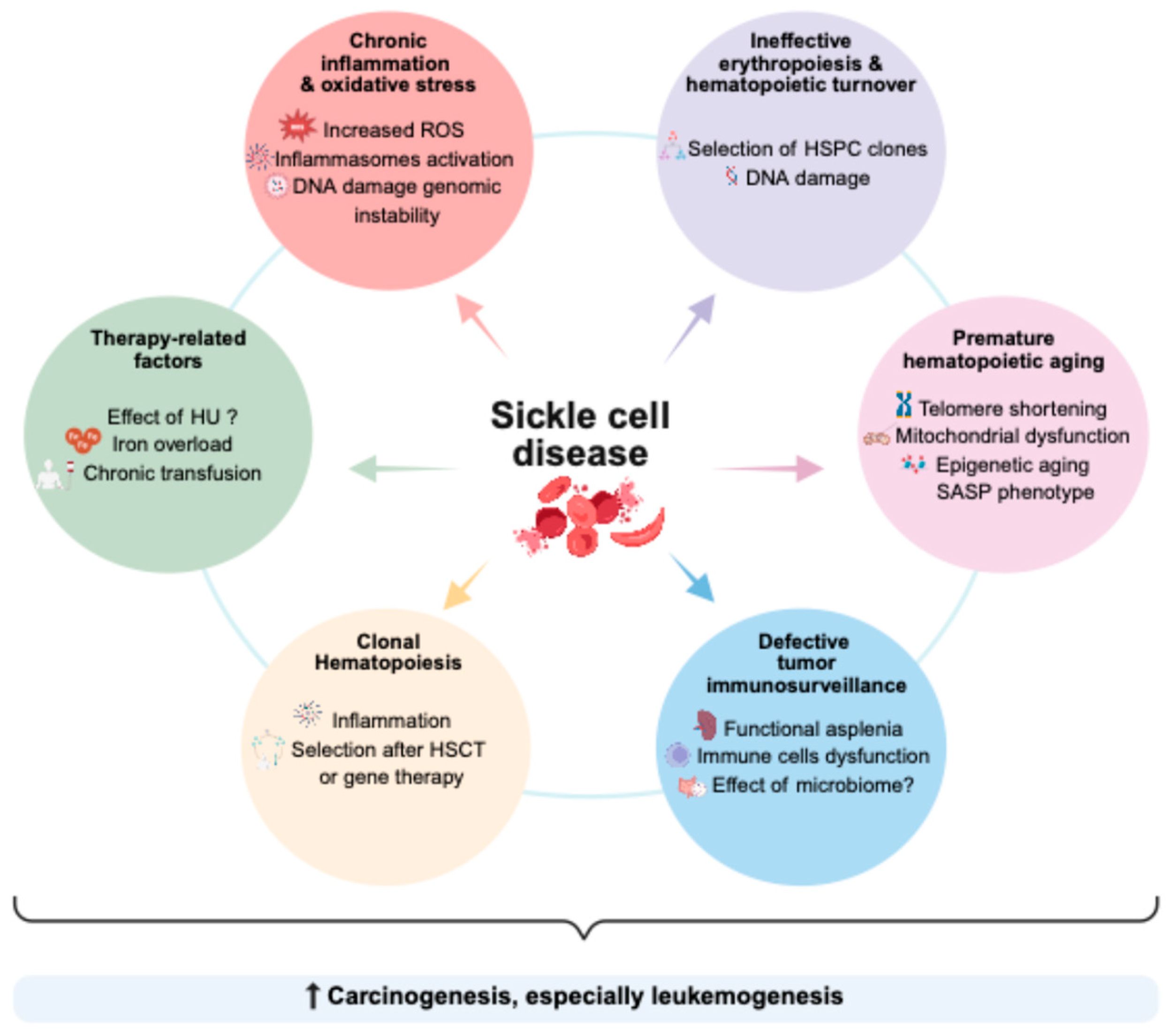

4. Potential Biological Mechanisms Underlying the Increased Cancer Risk

4.1. Chronic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

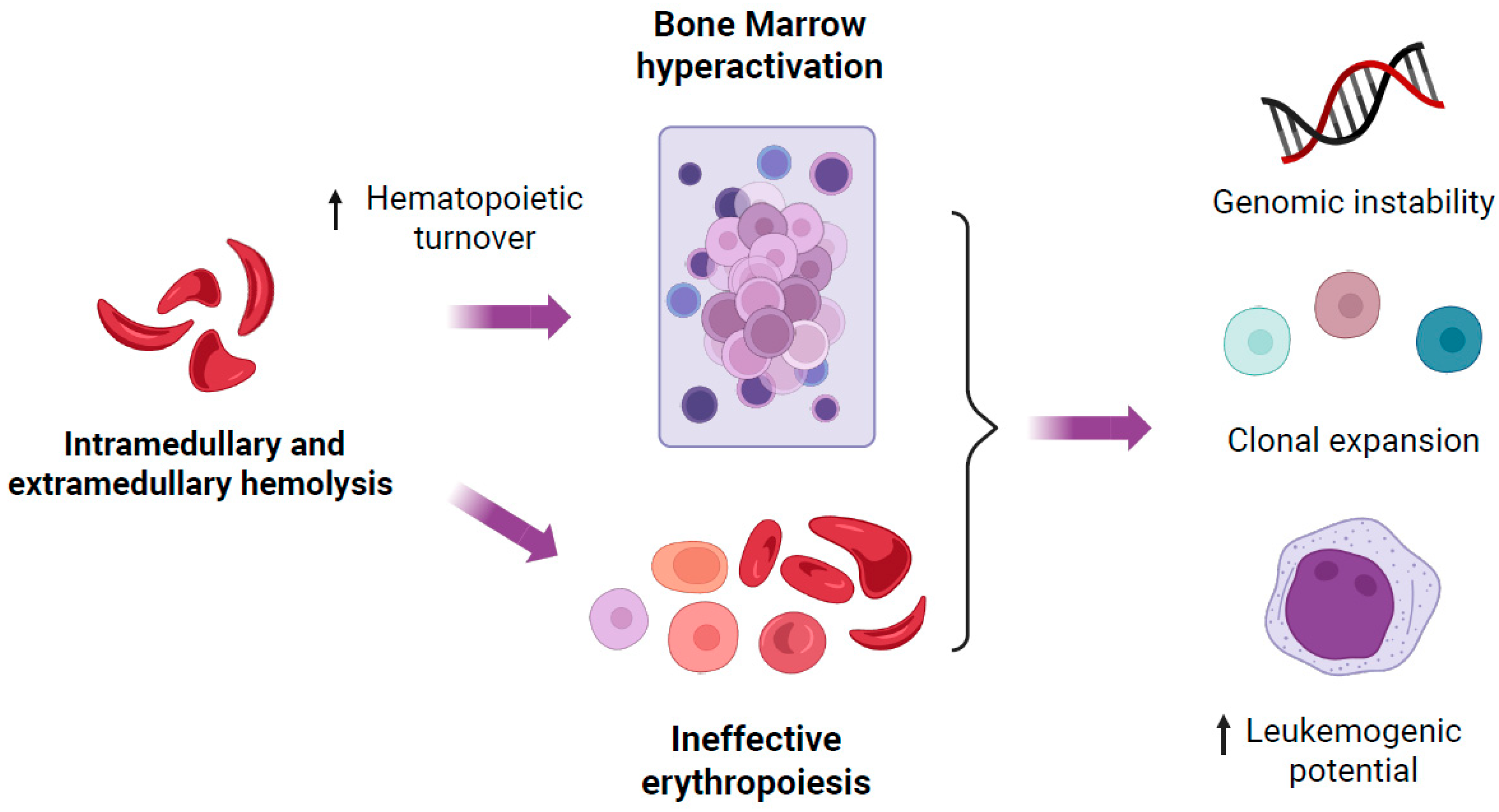

4.2. Increased Hematopoietic Turnover and Ineffective Erythropoiesis

4.3. Premature Hematopoietic Aging

4.4. Defect in Tumoral Immunosurveillance

4.5. Clonal Hematopoiesis in Sickle Cell Disease

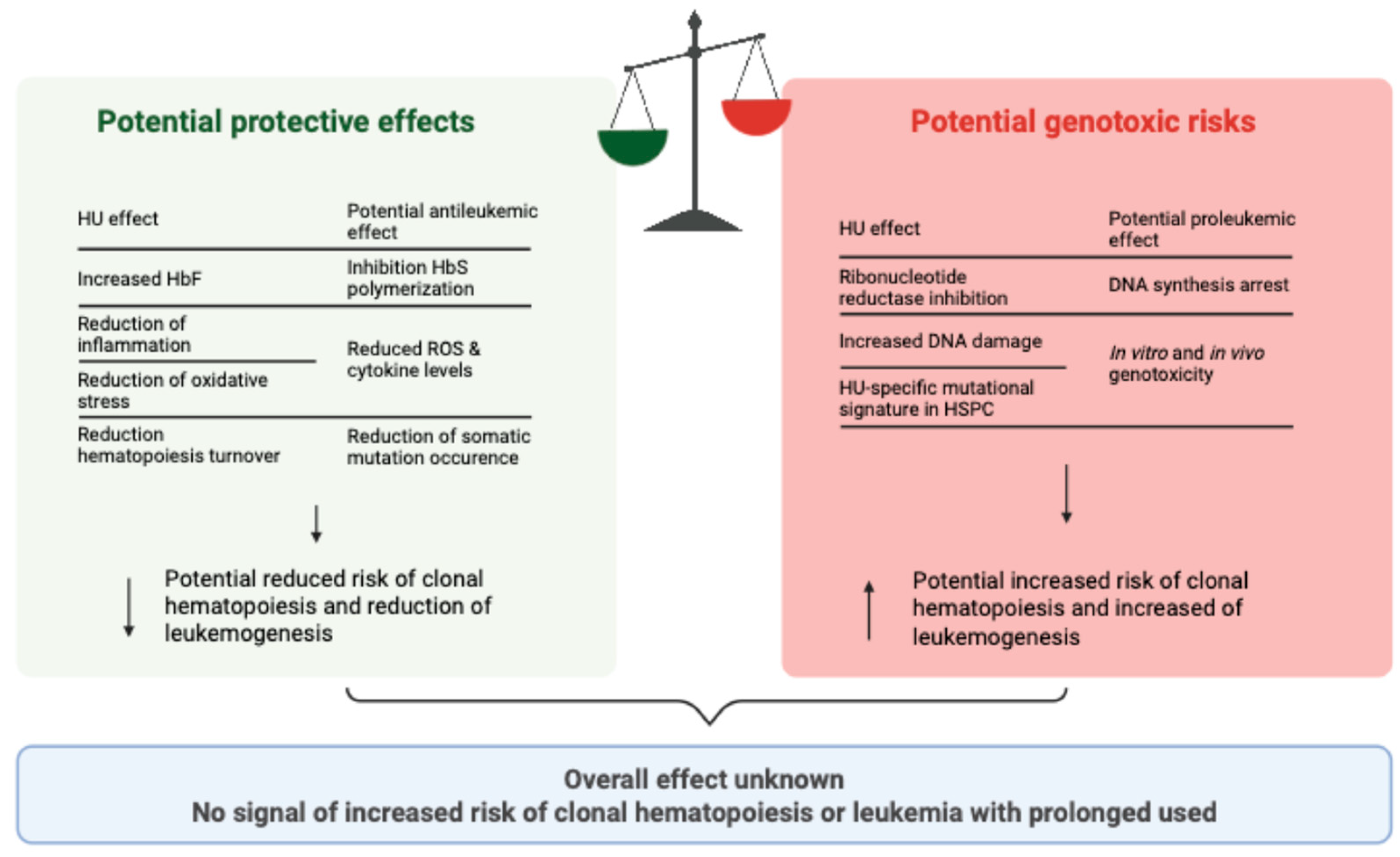

5. Impact of Therapeutic Exposures on the Risk of Malignant Transformation

5.1. Does Hydroxyurea Have an Effect, and if So, Is It Protective or Damaging?

5.2. Impact of Chronic Transfusions and Iron Overload

5.3. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Intensive Therapeutic Regimens

6. Conclusions, Perspectives, and Clinical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piel, F.B.; Steinberg, M.H.; Rees, D.C. Sickle Cell Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, G.J.; Piel, F.B.; Reid, C.D.; Gaston, M.H.; Ohene-Frempong, K.; Krishnamurti, L.; Smith, W.R.; Panepinto, J.A.; Weatherall, D.J.; Costa, F.F.; et al. Sickle cell disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nemer, W.; Godard, A.; El Hoss, S. Ineffective erythropoiesis in sickle cell disease: New insights and future implications. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2021, 28, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, I.M.; Botchwey, E.A.; Hyacinth, H.I. Sickle cell disease as an accelerated aging syndrome. Exp. Biol. Med. 2022, 247, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, A.M.; McHugh, T.A.; Oron, A.P.; Teply, C.; Lonberg, N.; Tella, V.V.; Wilner, L.B.; Fuller, K.; Hagins, H.; Aboagye, R.G.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000–2021: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023, 10, e585–e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, K.; Douiri, A.; Drasar, E.; Allman, M.; Mwirigi, A.; Awogbade, M.; Thein, S.L. Survival in adults with sickle cell disease in a high-income setting. Blood 2016, 128, 1436–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thein, M.S.; Igbineweka, N.E.; Thein, S.L. Sickle cell disease in the older adult. Pathology 2017, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedeji, C.I.; Hodulik, K.L.; Telen, M.J.; Strouse, J.J. Management of Older Adults with Sickle Cell Disease: Considerations for current and emerging therapies. Drugs Aging 2023, 40, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, F.W.; Kim, K.S.; Squires, R.S.; Chisholm, R.; Kark, J.A.; Perlin, E.; Castro, O. Cancer incidence rate and mortality rate in sickle cell disease patients at Howard University Hospital: 1986–1995. Am. J. Hematol. 1997, 55, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W.H.; Ware, R.E. Malignancy in patients with sickle cell disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2003, 74, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminog, O.O.; Ogunlaja, O.I.; Yeates, D.; Goldacre, M.J. Risk of individual malignant neoplasms in patients with sickle cell disease: English national record linkage study. J. R. Soc. Med. 2016, 109, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunson, A.; Keegan, T.H.M.; Bang, H.; Mahajan, A.; Paulukonis, S.; Wun, T. Increased risk of leukemia among sickle cell disease patients in California. Blood 2017, 130, 1597–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merolle, L.; Ghirotto, L.; Schiroli, D.; Balestra, G.L.; Venturelli, F.; Bassi, M.C.; Di Bartolomeo, E.; Baricchi, R.; Marraccini, C. Risk of cancer in patients with thalassemia and sickle cell disease: A systematic review. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2522967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Origa, R.; Gianesin, B.; Longo, F.; Di Maggio, R.; Cassinerio, E.; Gamberini, M.R.; Pinto, V.M.; Quarta, A.; Casale, M.; La Nasa, G.; et al. Incidence of cancer and related deaths in hemoglobinopathies: A follow-up of 4631 patients between 1970 and 2021. Cancer 2023, 129, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.-M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.E.; Short, B.J. Frequency and prognosis of coexisting sickle cell disease and acute leukemia in children. Clin. Pediatr. 1972, 11, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samal, G.C. Sickle cell anemia with acute myeloid leukemia–(a case report). Indian Pediatr. 1979, 16, 453–454. [Google Scholar]

- Deuel, T.; Rodgers, J.; Jost, R.G.; Kumar, B.; Markham, R. Left elbow pain and death in a young woman with sickle-cell anemia. Am. J. Med. 1982, 73, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, F.L.; Look, A.T.; Gockerman, J.; Ruggiero, M.R.; Dalla-Pozza, L.; Billings, F.T. Bone-marrow transplantation in a patient with sickle-cell anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984, 311, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigner, S.H.; Friedman, H.S.; Kinney, T.R.; Kurtzberg, J.; Chaffee, S.; Becton, D.; Falletta, J.M. 9p- in a girl with acute lymphocytic leukemia and sickle cell disease. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 1986, 21, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stricker, R.B.; Linker, C.A.; Crowley, T.J.; Embury, S.H. Hematologic malignancy in sickle cell disease: Report of four cases and review of the literature. Am. J. Hematol. 1986, 21, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, O.S.; Johnson, S.B.; Kulkarni, A.G.; Mba, E.C. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in a Nigerian adult with sickle cell anaemia. Cent. Afr. J. Med. 1988, 34, 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sotomayor, E.A.; Glasser, L. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in sickle cell disease. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1999, 123, 745–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Montalembert, M.; Bégué, P.; Bernaudin, F.; Thuret, I.; Bachir, D.; Micheau, M. Preliminary report of a toxicity study of hydroxyurea in sickle cell disease. French Study Group on Sickle Cell Disease. Arch. Dis. Child. 1999, 81, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauch, A.; Borromeo, M.; Ghafoor, A.; Khoyratty, B.; Maheshwari, J. Leukemogenesis of hydroxyurea in the treatment of sickle cell anemia. Blood 1999, 94, 415a. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. Acute leukemia in a patient with sickle-cell anemia treated with hydroxyurea. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 133, 925–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jam’a, A.H.; Al-Dabbous, I.A.; Al-Khatti, A.A.; Esan, F.G. Are we underestimating the leukemogenic risk of hydroxyurea. Saudi Med. J. 2002, 23, 1411–1413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferster, A.; Sariban, E.; Meuleman, N. Belgian Registry of Sickle Cell Disease patients treated with Hydroxyurea Malignancies in sickle cell disease patients treated with hydroxyurea. Br. J. Haematol. 2003, 123, 368–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.G.; Darbari, D.S.; Maric, I.; McIver, Z.; Arthur, D.C. Therapy-related acute myelogenous leukemia in a hydroxyurea-treated patient with sickle cell anemia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 722–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baz, W.; Najfeld, V.; Yotsuya, M.; Talwar, J.; Terjanian, T.; Forte, F. Development of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia 15 years after hydroxyurea use in a patient with sickle cell anemia. Clin. Med. Insights Oncol. 2012, 6, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemenides, S.; Erblich, T.; Luqmani, A.; Bain, B.J. Peripheral blood features of acute myeloid leukemia with myelodysplasia-related changes developing in a patient with sickle cell anemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2014, 89, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aumont, C.; Driss, F.; Lazure, T.; Picard, V.; Creidy, R.; De Botton, S.; Saada, V.; Lambotte, O.; Bilhou-Nabera, C.; Tertian, G.; et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome with clonal cytogenetic abnormalities followed by fatal erythroid leukemia after 14 years of exposure to hydroxyurea for sickle cell anemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2015, 90, E131–E132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Swain, S.K.; Sahu, M.C. Incidence of hematological malignancies in sickle cell patients from an indian tertiary care teaching hospital. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Janakiram, M.; Verma, A.; Wang, Y.; Budhathoki, A.; Suarez Londono, J.; Murakhovskaya, I.; Braunschweig, I.; Minniti, C.P. Accelerated leukemic transformation after haplo-identical transplantation for hydroxyurea-treated sickle cell disease. Leuk Lymphoma 2018, 59, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Maule, J.; Neff, J.L.; McCall, C.M.; Rapisardo, S.; Lagoo, A.S.; Yang, L.-H.; Crawford, R.D.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, E. Myeloid neoplasms in the setting of sickle cell disease: An intrinsic association with the underlying condition rather than a coincidence; report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 32, 1712–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eapen, M.; Brazauskas, R.; Walters, M.C.; Bernaudin, F.; Bo-Subait, K.; Fitzhugh, C.D.; Hankins, J.S.; Kanter, J.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Bolaños-Meade, J.; et al. Effect of donor type and conditioning regimen intensity on allogeneic transplantation outcomes in patients with sickle cell disease: A retrospective multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2019, 6, e585–e596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, S.; Yang, X.; Finnberg, N.K.; El-Deiry, W.S.; Pu, J.J. Occurrence of acute myeloid leukemia in hydroxyurea-treated sickle cell disease patient. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworanti, O.W.; Fasola, F.A.; Kotila, T.R.; Olaniyi, J.A.; Brown, B.J. Acute leukemia in sickle cell disease patients in a tertiary health facility in Nigeria: A case series. Afr. Health Sci. 2020, 20, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.K.; Paul, T.; Alhamar, M.; Inamdar, K.; Guo, Y. Pure Erythroid Leukemia in a Sickle Cell Patient Treated with Hydroxyurea. Case Rep. Oncol. 2020, 13, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannam, J.Y.; Xu, X.; Maric, I.; Dillon, L.; Li, Y.; Hsieh, M.M.; Hourigan, C.S.; Fitzhugh, C.D. Baseline TP53 mutations in adults with SCD developing myeloid malignancy following hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 2020, 135, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chellapandian, D.; Nicholson, C.L. Haploidentical bone marrow transplantation in a patient with sickle cell disease and acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr. Transpl. 2020, 24, e13641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.M.; Bonner, M.; Pierciey, F.J.; Uchida, N.; Rottman, J.; Demopoulos, L.; Schmidt, M.; Kanter, J.; Walters, M.C.; Thompson, A.A.; et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome unrelated to lentiviral vector in a patient treated with gene therapy for sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 2058–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.O.; Ochogwu, L.O.; Owojuyigbe, T.O.; Akinola, N.O.; Durosinmi, M.A. Philadelphia chromosome-positive B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with e1a3 BCR-ABL1 transcript in a Nigerian with sickle cell anemia: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Tisdale, J.; Schmidt, M.; Kanter, J.; Jaroscak, J.; Whitney, D.; Bitter, H.; Gregory, P.D.; Parsons, G.; Foos, M.; et al. Acute Myeloid Leukemia Case after Gene Therapy for Sickle Cell Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flevari, P.; Voskaridou, E.; Galactéros, F.; Cannas, G.; Loko, G.; Joseph, L.; Bartolucci, P.; Gellen-Dautremer, J.; Bernit, E.; Charneau, C.; et al. Case Report of Myelodysplastic Syndrome in a Sickle-Cell Disease Patient Treated with Hydroxyurea and Literature Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, G.; Poutrel, S.; Heiblig, M.; Labussière, H.; Larcher, M.-V.; Thomas, X.; Hot, A. Sickle cell disease and acute leukemia: One case report and an extensive review. Ann. Hematol. 2023, 102, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhary, M.; Turak, E.; Ibrahim, R.; Rashed, A.; Abdelhadi, M.; Ozturk, C.; Sudha, S.; Kaynar, L.; Fadel, E. Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia in a Patient With Sickle Cell Hemoglobin D Disease: A Case Report. Cureus 2025, 17, e87513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiocco, G.; Goel, R.; Azhar, W.; Shah, E.; Hussain, M.J.; Roubinian, N.; Josephson, C.; Fasano, R.M.; McLemore, M.L. Co-Diagnosis of Sickle Cell and Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia: Exploratory Analysis from a Nationally Representative Database. Blood 2023, 142, 5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasik, J.; Basak, G.W. Inflammasomes-New Contributors to Blood Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conran, N.; Belcher, J.D. Inflammation in Sickle Cell Disease. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2018, 68, 263–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allali, S.; Rignault-Bricard, R.; de Montalembert, M.; Taylor, M.; Bouceba, T.; Hermine, O.; Maciel, T.T. HbS promotes TLR4-mediated monocyte activation and proinflammatory cytokine production in sickle cell disease. Blood 2022, 140, 1972–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, J.; Thadhani, E.; Samson, L.; Engelward, B. Inflammation-Induced DNA Damage, Mutations and Cancer. DNA Repair 2019, 83, 102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.C.; Granger, D.N. Sickle cell disease: Role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen metabolites. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2007, 34, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nur, E.; Biemond, B.J.; Otten, H.-M.; Brandjes, D.P.; Schnog, J.-J.B. CURAMA Study Group Oxidative stress in sickle cell disease; pathophysiology and potential implications for disease management. Am. J. Hematol. 2011, 86, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xu, C.; Manwani, D.; Frenette, P.S. Neutrophils, platelets, and inflammatory pathways at the nexus of sickle cell disease pathophysiology. Blood 2016, 127, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavitra, E.; Acharya, R.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Verma, H.K.; Kang, H.; Lee, J.-H.; Sahu, T.; Bhaskar, L.; Raju, G.S.R.; Huh, Y.S. Impacts of oxidative stress and anti-oxidants on the development, pathogenesis, and therapy of sickle cell disease: A comprehensive review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Boasiako, C.; B. Dankwah, G.; Aryee, R.; Hayfron-Benjamin, C.; S. Donkor, E.; D. Campbell, A. Oxidative Profile of Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.J.; Kabeer, A.; Abbas, Z.; Siddiqui, H.A.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cho, W.C. Interplay of oxidative stress, cellular communication and signaling pathways in cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Weng, J.; You, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wen, J.; Xia, Z.; Huang, S.; Luo, P.; Cheng, Q. Oxidative stress in cancer: From tumor and microenvironment remodeling to therapeutic frontiers. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.M.; Martins, P.R.J.; da Luz Dias, F.; Burbano, R.M.R.; de Lourdes Pires Bianchi, M.; Antunes, L.M.G. Sensitivity to cisplatin-induced mutations and elevated chromosomal aberrations in lymphocytes from sickle cell disease patients. Clin. Exp. Med. 2008, 8, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, D.; Lier, A.; Geiselhart, A.; Thalheimer, F.B.; Huntscha, S.; Sobotta, M.C.; Moehrle, B.; Brocks, D.; Bayindir, I.; Kaschutnig, P.; et al. Exit from dormancy provokes DNA-damage-induced attrition in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2015, 520, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoss, S.E.; Cochet, S.; Godard, A.; Yan, H.; Dussiot, M.; Frati, G.; Boutonnat-Faucher, B.; Laurance, S.; Renaud, O.; Joseph, L.; et al. Fetal hemoglobin rescues ineffective erythropoiesis in sickle cell disease. Haematologica 2021, 106, 2707–2719. Available online: https://haematologica.org/article/view/9915 (accessed on 24 September 2020). [CrossRef]

- El Hoss, S.; Shangaris, P.; Brewin, J.; Psychogyiou, M.E.; Ng, C.; Pedler, L.; Rooks, H.; Gotardo, É.M.F.; Gushiken, L.F.S.; Brito, P.L.; et al. Reduced GATA1 levels are associated with ineffective erythropoiesis in sickle cell anemia. Haematologica 2025, 110, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attardi, E.; Corey, S.J.; Wlodarski, M.W. Clonal hematopoiesis in children with predisposing conditions. Semin. Hematol. 2024, 61, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Kotzin, J.J.; Ramdas, B.; Chen, S.; Nelanuthala, S.; Palam, L.R.; Pandey, R.; Mali, R.S.; Liu, Y.; Kelley, M.R.; et al. Inhibition of Inflammatory Signaling in Tet2 Mutant Preleukemic Cells Mitigates Stress-Induced Abnormalities and Clonal Hematopoiesis. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 833–849.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattangadi, S.M.; Wong, P.; Zhang, L.; Flygare, J.; Lodish, H.F. From stem cell to red cell: Regulation of erythropoiesis at multiple levels by multiple proteins, RNAs, and chromatin modifications. Blood 2011, 118, 6258–6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Ginzburg, Y.; Li, H.; Xue, F.; De Franceschi, L.; Chasis, J.A.; Mohandas, N.; An, X. Quantitative analysis of murine terminal erythroid differentiation in vivo: Novel method to study normal and disordered erythropoiesis. Blood 2013, 121, e43–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodroj, M.H.; Bou-Fakhredin, R.; Nour-Eldine, W.; Noureldine, H.A.; Noureldine, M.H.A.; Taher, A.T. Thalassemia and malignancy: An emerging concern? Blood Rev. 2019, 37, 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, L.; Cheng, T. How age affects human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and the strategies to mitigate aging. Exp. Hematol. 2025, 143, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmich, C.; Moore, J.A.; Bowles, K.M.; Rushworth, S.A. Bone Marrow Senescence and the Microenvironment of Hematological Malignancies. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 230. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.00230/full (accessed on 16 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vB Hjelmborg, J.; Iachine, I.; Skytthe, A.; Vaupel, J.W.; McGue, M.; Koskenvuo, M.; Kaprio, J.; Pedersen, N.L.; Christensen, K. Genetic influence on human lifespan and longevity. Hum. Genet. 2006, 119, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekontso Dessap, A.; Cecchini, J.; Chaar, V.; Marcos, E.; Habibi, A.; Bartolucci, P.; Ghaleh, B.; Galacteros, F.; Adnot, S. Telomere attrition in sickle cell anemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2017, 92, E112–E114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colella, M.P.; Santana, B.A.; Conran, N.; Tomazini, V.; Costa, F.F.; Calado, R.T.; Saad, S.T.O. Telomere length correlates with disease severity and inflammation in sickle cell disease. Rev. Bras. Hematol. Hemoter. 2017, 39, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warang, P.; Homma, T.; Pandya, R.; Sawant, A.; Shinde, N.; Pandey, D.; Fujii, J.; Madkaikar, M.; Mukherjee, M.B. Potential involvement of ubiquitin-proteasome system dysfunction associated with oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of sickle cell disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 182, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.; Kıraç, E.; Kaya, S.; Özcan, F.; Salim, O.; Küpesiz, O.A. Decreased Serum Levels of Sphingomyelins and Ceramides in Sickle Cell Disease Patients. Lipids 2018, 53, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lê, B.M.; Hatch, D.; Yang, Q.; Shah, N.; Luyster, F.S.; Garrett, M.E.; Tanabe, P.; Ashley-Koch, A.E.; Knisely, M.R. Characterizing epigenetic aging in an adult sickle cell disease cohort. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colom Díaz, P.A.; Mistry, J.J.; Trowbridge, J.J. Hematopoietic stem cell aging and leukemia transformation. Blood 2023, 142, 533–542, Erratum in Blood 2024, 143, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brousse, V.; Buffet, P.; Rees, D. The spleen and sickle cell disease: The sick(led) spleen. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 166, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottenstreich, A.; Kleinstern, G.; Spectre, G.; Da’as, N.; Ziv, E.; Kalish, Y. Thromboembolic Events Following Splenectomy: Risk Factors, Prevention, Management and Outcomes. World J. Surg. 2018, 42, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, R.F.; Gangnon, R.E.; Traver, M.I. Delayed adverse vascular events after splenectomy in hereditary spherocytosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2008, 6, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Barmparas, G.; Fierro, N.; Sun, B.J.; Ashrafian, S.; Li, T.; Ley, E.J. Splenectomy is associated with a higher risk for venous thromboembolism: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 24, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, S.; White, R.H.; Brunson, A.; Wun, T. Splenectomy and the incidence of venous thromboembolism and sepsis in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2013, 121, 4782–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourdieu, C.; El Hoss, S.; Le Roux, E.; Pages, J.; Koehl, B.; Missud, F.; Holvoet, L.; Ithier, G.; Benkerrou, M.; Haouari, Z.; et al. Relevance of Howell-Jolly body counts for measuring spleen function in sickle cell disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, E110–E112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristinsson, S.Y.; Gridley, G.; Hoover, R.N.; Check, D.; Landgren, O. Long-term risks after splenectomy among 8,149 cancer-free American veterans: A cohort study with up to 27 years follow-up. Haematologica 2014, 99, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Chandrakar, D.; Wasnik, P.N.; Nayak, S.; Shah, S.; Nanda, R.; Mohapatra, E. Altered T-cell profile in sickle cell disease. Biomark. Med. 2023, 17, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Azevedo, J.T.C.; Malmegrim, K.C.R. Immune mechanisms involved in sickle cell disease pathogenesis: Current knowledge and perspectives. Immunol. Lett. 2020, 224, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vingert, B.; Tamagne, M.; Desmarets, M.; Pakdaman, S.; Elayeb, R.; Habibi, A.; Bernaudin, F.; Galacteros, F.; Bierling, P.; Noizat-Pirenne, F.; et al. Partial dysfunction of Treg activation in sickle cell disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2014, 89, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Hu, B.; Deng, Y.; Soeung, M.; Yao, J.; Bei, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, P.; Huang, L.A.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Sickle cell disease induces chromatin introversion and ferroptosis in CD8+ T cells to suppress anti-tumor immunity. Immunity 2025, 58, 1484–1501.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Aujla, A.; Knoll, B.M.; Lim, S.H. Intestinal pathophysiological and microbial changes in sickle cell disease: Potential targets for therapeutic intervention. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 188, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.; Morris, A.; Li, K.; Fitch, A.C.; Fast, L.; Goldberg, L.; Quesenberry, M.; Sprinz, P.; Methé, B. Intestinal microbiome analysis revealed dysbiosis in sickle cell disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2018, 93, E91–E93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobels, A.; van Marcke, C.; Jordan, B.F.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. The gut microbiome and cancer: From tumorigenesis to therapy. Nat. Metab. 2025, 7, 895–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandalai, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, N.; Peng, H.; Zheng, Q. The human microbiome and cancer: A diagnostic and therapeutic perspective. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2023, 24, 2240084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todor, S.B.; Ichim, C. Microbiome Modulation in Pediatric Leukemia: Impact on Graft-Versus-Host Disease and Treatment Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Children 2025, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.; Freeman, B.A. Redox-dependent impairment of vascular function in sickle cell disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 43, 1469–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, S.; Ebert, B.L. Clonal hematopoiesis in human aging and disease. Science 2019, 366, eaan4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, C.J.; Steensma, D.P. New Insights from Studies of Clonal Hematopoiesis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 4633–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Fontanillas, P.; Flannick, J.; Manning, A.; Grauman, P.V.; Mar, B.G.; Lindsley, R.C.; Mermel, C.H.; Burtt, N.; Chavez, A.; et al. Age-Related Clonal Hematopoiesis Associated with Adverse Outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2488–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, G.; Kähler, A.K.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lindberg, J.; Rose, S.A.; Bakhoum, S.F.; Chambert, K.; Mick, E.; Neale, B.M.; Fromer, M.; et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2477–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.D.; Lindsley, R.C. Clonal hematopoiesis in the inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood 2020, 136, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizato, T.; Dumitriu, B.; Hosokawa, K.; Makishima, H.; Yoshida, K.; Townsley, D.; Sato-Otsubo, A.; Sato, Y.; Liu, D.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Somatic Mutations and Clonal Hematopoiesis in Aplastic Anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Natarajan, P.; Silver, A.J.; Gibson, C.J.; Bick, A.G.; Shvartz, E.; McConkey, M.; Gupta, N.; Gabriel, S.; Ardissino, D.; et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombs, C.C.; Zehir, A.; Devlin, S.M.; Kishtagari, A.; Syed, A.; Jonsson, P.; Hyman, D.M.; Solit, D.B.; Robson, M.E.; Baselga, J.; et al. Therapy-Related Clonal Hematopoiesis in Patients with Non-hematologic Cancers Is Common and Associated with Adverse Clinical Outcomes. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 374–382.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challen, G.A.; Goodell, M.A. Clonal hematopoiesis: Mechanisms driving dominance of stem cell clones. Blood 2020, 136, 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pincez, T.; Lee, S.S.K.; Ilboudo, Y.; Preuss, M.; Pham Hung d’Alexandry d’Orengiani, A.-L.; Bartolucci, P.; Galactéros, F.; Joly, P.; Bauer, D.E.; Loos, R.J.F.; et al. Clonal hematopoiesis in sickle cell disease. Blood 2021, 138, 2148–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liggett, L.A.; Cato, L.D.; Weinstock, J.S.; Zhang, Y.; Nouraie, S.M.; Gladwin, M.T.; Garrett, M.E.; Ashley-Koch, A.; Telen, M.J.; Custer, B.; et al. Clonal hematopoiesis in sickle cell disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e156060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.N.; Ramsingh, G.; Young, A.L.; Miller, C.A.; Touma, W.; Welch, J.S.; Lamprecht, T.L.; Shen, D.; Hundal, J.; Fulton, R.S.; et al. Role of TP53 mutations in the origin and evolution of therapy-related acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2015, 518, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, D.H.; Andersen, M.K.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, J. Mutations with loss of heterozygosity of p53 are common in therapy-related myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia after exposure to alkylating agents and significantly associated with deletion or loss of 5q, a complex karyotype, and a poor prognosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer Chapman, M.; Cull, A.H.; Ciuculescu, M.F.; Esrick, E.B.; Mitchell, E.; Jung, H.; O’Neill, L.; Roberts, K.; Fabre, M.A.; Williams, N.; et al. Clonal selection of hematopoietic stem cells after gene therapy for sickle cell disease. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 3175–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondek, L.P.; Sheehan, V.A.; Fitzhugh, C.D. Clonal Hematopoiesis and the Risk of Hematologic Malignancies after Curative Therapies for Sickle Cell Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, N.S.; Barral, S. Emerging science of hydroxyurea therapy for pediatric sickle cell disease. Pediatr. Res. 2014, 75, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, M.H.; Barton, F.; Castro, O.; Pegelow, C.H.; Ballas, S.K.; Kutlar, A.; Orringer, E.; Bellevue, R.; Olivieri, N.; Eckman, J.; et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on mortality and morbidity in adult sickle cell anemia: Risks and benefits up to 9 years of treatment. JAMA 2003, 289, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charache, S.; Terrin, M.L.; Moore, R.D.; Dover, G.J.; Barton, F.B.; Eckert, S.V.; McMahon, R.P.; Bonds, D.R. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 1317–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferster, A.; Vermylen, C.; Cornu, G.; Buyse, M.; Corazza, F.; Devalck, C.; Fondu, P.; Toppet, M.; Sariban, E. Hydroxyurea for treatment of severe sickle cell anemia: A pediatric clinical trial. Blood 1996, 88, 1960–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.; Ware, R.E.; Miller, S.T.; Iyer, R.V.; Casella, J.F.; Minniti, C.P.; Rana, S.; Thornburg, C.D.; Rogers, Z.R.; Kalpatthi, R.V.; et al. Hydroxycarbamide in very young children with sickle-cell anaemia: A multicentre, randomised, controlled trial (BABY HUG). Lancet 2011, 377, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Rocha, L.B.; Dias Elias, D.B.; Barbosa, M.C.; Bandeira, I.C.J.; Gonçalves, R.P. DNA damage in leukocytes of sickle cell anemia patients is associated with hydroxyurea therapy and with HBB*S haplotype. Mutat. Res. 2012, 749, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia Filho, P.A.; Pereira, J.F.; de Almeida Filho, T.P.; Cavalcanti, B.C.; de Sousa, J.C.; Lemes, R.P.G. Is chronic use of hydroxyurea safe for patients with sickle cell anemia? An account of genotoxicity and mutagenicity. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2019, 60, 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature 2005, 438, 932–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, M.F.; Ozdemir, A.C.; Birkeland, S.R.; Wilson, T.E.; Glover, T.W. Hydroxyurea induces de novo copy number variants in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 17360–17365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlt, M.F.; Rajendran, S.; Holmes, S.N.; Wang, K.; Bergin, I.L.; Ahmed, S.; Wilson, T.E.; Glover, T.W. Effects of hydroxyurea on CNV induction in the mouse germline. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2018, 59, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, M.H.; McCarthy, W.F.; Castro, O.; Ballas, S.K.; Armstrong, F.D.; Smith, W.; Ataga, K.; Swerdlow, P.; Kutlar, A.; DeCastro, L.; et al. The risks and benefits of long-term use of hydroxyurea in sickle cell anemia: A 17.5 year follow-up. Am. J. Hematol. 2010, 85, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzkron, S.; Strouse, J.J.; Wilson, R.; Beach, M.C.; Haywood, C.; Park, H.; Witkop, C.; Bass, E.B.; Segal, J.B. Systematic review: Hydroxyurea for the treatment of adults with sickle cell disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 148, 939–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voskaridou, E.; Christoulas, D.; Bilalis, A.; Plata, E.; Varvagiannis, K.; Stamatopoulos, G.; Sinopoulou, K.; Balassopoulou, A.; Loukopoulos, D.; Terpos, E. The effect of prolonged administration of hydroxyurea on morbidity and mortality in adult patients with sickle cell syndromes: Results of a 17-year, single-center trial (LaSHS). Blood 2010, 115, 2354–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, O.; Nouraie, M.; Oneal, P. Hydroxycarbamide treatment in sickle cell disease: Estimates of possible leukaemia risk and of hospitalization survival benefit. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 167, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Montalembert, M.; Voskaridou, E.; Oevermann, L.; Cannas, G.; Habibi, A.; Loko, G.; Joseph, L.; Colombatti, R.; Bartolucci, P.; Brousse, V.; et al. Real-Life experience with hydroxyurea in patients with sickle cell disease: Results from the prospective ESCORT-HU cohort study. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiladjian, J.-J.; Chevret, S.; Dosquet, C.; Chomienne, C.; Rain, J.-D. Treatment of polycythemia vera with hydroxyurea and pipobroman: Final results of a randomized trial initiated in 1980. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3907–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawn, B.P.; Buchanan, G.R.; Afenyi-Annan, A.N.; Ballas, S.K.; Hassell, K.L.; James, A.H.; Jordan, L.; Lanzkron, S.M.; Lottenberg, R.; Savage, W.J.; et al. Management of Sickle Cell Disease: Summary of the 2014 Evidence-Based Report by Expert Panel Members. JAMA 2014, 312, 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincez, T.; Pastore, Y.D. Molecular Testing in Sickle Cell Disease: From Newborn Screening to Transfusion Care. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2025; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaris, D.; Barbouti, A.; Pantopoulos, K. Iron homeostasis and oxidative stress: An intimate relationship. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, L.; Oliveira, M.M.; Pessôa, M.T.C.; Barbosa, L.A. Iron overload: Effects on cellular biochemistry. Clinica Chimica Acta 2020, 504, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ru, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Iron homeostasis and ferroptosis in human diseases: Mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Li, D.; Cao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Mu, J.; Lu, W.; Xiao, X.; Li, C.; Meng, J.; Chen, J.; et al. ROS-mediated iron overload injures the hematopoiesis of bone marrow by damaging hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in mice. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taoka, K.; Kumano, K.; Nakamura, F.; Hosoi, M.; Goyama, S.; Imai, Y.; Hangaishi, A.; Kurokawa, M. The effect of iron overload and chelation on erythroid differentiation. Int. J. Hematol. 2012, 95, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, E.; Cappelli, B.; Bernaudin, F.; Labopin, M.; Volt, F.; Carreras, J.; Pinto Simões, B.; Ferster, A.; Dupont, S.; de la Fuente, J.; et al. Sickle cell disease: An international survey of results of HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2017, 129, 1548–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhail, N.S. Secondary cancers following allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation in adults. Br. J. Haematol. 2011, 154, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhail, N.S.; Brazauskas, R.; Rizzo, J.D.; Sobecks, R.M.; Wang, Z.; Horowitz, M.M.; Bolwell, B.; Wingard, J.R.; Socie, G. Secondary solid cancers after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation using busulfan-cyclophosphamide conditioning. Blood 2011, 117, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, D.L.; Leisenring, W.; Schwartz, J.L.; Deeg, H.J. Second malignant neoplasms following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int. J. Hematol. 2004, 79, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNerney, M.E.; Godley, L.A.; Le Beau, M.M. Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms: When genetics and environment collide. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer Chapman, M.; Wilk, C.M.; Boettcher, S.; Mitchell, E.; Dawson, K.; Williams, N.; Müller, J.; Kovtonyuk, L.; Jung, H.; Caiado, F.; et al. Clonal dynamics after allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation. Nature 2024, 635, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.J.; DeBaun, M.R. Leukemia after gene therapy for sickle cell disease: Insertional mutagenesis, busulfan, both, or neither. Blood 2021, 138, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, J.; Walters, M.C.; Krishnamurti, L.; Mapara, M.Y.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Rifkin-Zenenberg, S.; Aygun, B.; Kasow, K.A.; Pierciey, F.J.; Bonner, M.; et al. Biologic and Clinical Efficacy of LentiGlobin for Sickle Cell Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pich, O.; Bernard, E.; Zagorulya, M.; Rowan, A.; Pospori, C.; Slama, R.; Encabo, H.H.; O’Sullivan, J.; Papazoglou, D.; Anastasiou, P.; et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Clonal Hematopoiesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1594–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzambi, R.; Bottle, A.; Dexter, D.; Augustine, C.; Joseph, J.; Dasaolu, F.; Carr, S.B.; Reynolds, C.; Sathyamoorthy, G.; James, J.; et al. Indicators of inequity in research and funding for sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis and haemophilia: A descriptive comparative study. Lancet Haematol. 2025, 12, e789–e797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugthart, S.; Ginete, C.; Kuona, P.; Brito, M.; Inusa, B.P.D. An update review of new therapies in sickle cell disease: The prospects for drug combinations. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.J.; Kim, H.T.; Zhao, L.; Murdock, H.M.; Hambley, B.; Ogata, A.; Madero-Marroquin, R.; Wang, S.; Green, L.; Fleharty, M.; et al. Donor Clonal Hematopoiesis and Recipient Outcomes After Transplantation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cancer Type | Brunson et al. (California) [12] SIR | Seminog et al. (England) [11] RR |

|---|---|---|

| AML | 3.59 | 10.69 |

| ALL | 1.83 | 2.72 |

| CLL | 4.83 | For all lymphoid leukemia |

| Solid tumors | 0.62 | - |

| Breast cancer | 0.54 | 0.51 |

| Lymphoma | 1.45 | Hodgkin lymphoma: 4.32 Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: 2.37 |

| Variable | Category | n (%) or Median (Range) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male/female | 18 (43%)/24 (57%) | M/F ratio = 0.75 |

| Sickle cell disease type | HbSS/HbSC/HbSβ0/HbSD | 41 (84%)/4 (8%)/3 (6%)/1 (2%) | |

| Age at leukemia diagnosis | Median (min–max) | 26 years (3–61) | |

| Prior SCD treatment | |||

| Hydroxyurea | 24 (58%) | Median duration: 6.5 years | |

| Chronic transfusion | 17 (32%) | ||

| HSCT | 10 (19%) | All with relapse or graft failure | |

| Gene therapy | 2 (4%) | Myeloablative conditioning | |

| Leukemia type | ALL/AML/MDS/MDS-AML overlap/other | 13/17/6/16/1 | 73% myeloid malignancies |

| AML subtype (ICC/WHO 2022 [15]) | AML-defining 1 | 20/39 (51%) | |

| Unfavorable cytogenetics | −5/−7/del17/complex | 20/27 (74%) | t-AML marker |

| Leukemia treatment | Chemotherapy alone | 16 (30%) | |

| HSCT | 9 (17%) | ||

| Azacitidine/low intensity | 4 (8%) | ||

| Supportive care/not reported | 24 (45%) | ||

| Complete remission (CR) | Yes | 60% | |

| OS | Median (range) | 7 months (4 days–2.5 years) | 12-month OS: 37.5% |

| Patient/Age/Sex | Type of Leukemia/MDS | Treatment | Outcome (Cause of Death) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6/F | ALL | Chemo | CR, OS: 17 months (viremia) | [16] |

| 7/F | AML | None | OS: 4 days | [17] |

| 27/F | MDS/AML4 | None | OS: 3 days (ARDS) | [18] |

| 8/F | AML2 | HSCT | OS: 16+ months | [19] |

| 4/F | ALL null (del9p13) | NA | NA | [20] |

| 43/M | MDS/AML1 (−3, t13;17, t3;5, 5q−, −7, +8) | Chemo | OS: 1 month (hemorrhage) | [21] |

| 22/M | ALL | Chemo | CR, OS: 10 months (progression) | [22] |

| 14/M | ALL (CD10+, CD19+, CD22+, DR+, TdT+) | Chemo | CR, OS: 2.5+ years | [23] |

| 10/F | Ph+ ALL | Chemo | CR, OS: 12+ months | [24] |

| 27/F | MDS/AML | NA | NA | [25] |

| 42/F | MDS/AML (−5, −7, del17) | Chemo | OS: 13 months | [26] |

| 25/F | AML1 (normal karyotype) | Chemo | CR, OS: NA (aspergillosis) | [27] |

| 14/F | ALL | NA | Alive | [10] |

| 5/NA | ALL | NA | Alive | |

| 7/NA | ALL | NA | Alive | |

| 8/NA | AML | NA | Alive | |

| 8/NA | ALL | NA | Alive | |

| 17/NA | ALL | NA | Alive | |

| 61/NA | ALL | NA | Dead | |

| 20/NA | AML | NA | Dead | |

| 21/F | AML3v | ATRA + Chemo | CR | [28] |

| 33/M | MDS/AML6 (Abn5q, del7q, −15, −22, −Y, mar5) | Chemo + Allo HSCT | CR, relapse at 4 m, OS: 9 m | [29] |

| 41/M | MDS/AML (Abn5, del7, −17) | Chemo | OS: 3 m (sepsis) | [30] |

| 55/M | MDS/AML (5q−, 7q−, del17p) | NA | NA | [31] |

| 49/M | MDS/AML6 (del17p, del5q, monosomy 20, BM fibrosis) | Chemo | OS: 3 w (CNS involvement) | [32] |

| 25/F | AML3 | NA | NA | [33] |

| 19/M | AML2 | NA | NA | |

| 31/F | MDS/AML (5q−, add5p, −7, t2;5, TP53+, NRas+) | Azacitidine | OS: 12 m (sepsis) | [34] |

| 59/F | MDS (del4, 5q−, 7q−, −15, −16, TP53+) | Decitabine | OS: 2 m (AML progression) | [35] |

| 27/M | MDS/AML (11q23, +3, +19, +21, KMT2A+) | Chemo + Allo HSCT | OS: 7 m | |

| 37/F | MDS (del1, del5, t3;6, −17, +3, TP53+) | Lenalidomide + prednisone | OS: 5+ m | |

| 34/M | MDS (7q22, del20, −2, Inv9) | Matched sibling HSCT | OS: 21+ m | |

| 19/NA | AML | NA | NA | * [36] |

| 37/NA | MDS | NA | NA | |

| 32/NA | AML | NA | NA | |

| 37/NA | MDS | NA | NA | |

| 26/F | MDS/AML (5q−, +8, del17, TP53 del) | Chemo | OS: 4 m | [37] |

| 15/M | AL mixed lineage | None | Death before treatment | [38] |

| 21/F | ALL | None | Discharged day 5 CR after 2 lines | |

| 15/M | AML4 | Chemo | CR, death 4 w later | |

| 3/M | AML | None | Discharged after diagnosis | |

| 15/F | AML5 | Chemo | OS: 2 m (sepsis) | |

| 29/F | AML6 (5q−) | Chemo | OS: a few months (AML progression) | [39] |

| 39/M | MDS/AML7 (complex cytogenetics, TP53+, BM fibrosis) | Decitabine + Azacitidine | OS: 12 m (pulmonary hypertension) | [40] |

| 39/M | MDS/AML (complex cytogenetics, TP53+) | Haplo HSCT | OS: 7 m (intracranial hemorrhage) | |

| 49/F | MDS/AML (7q−, BM fibrosis) | NA | NA | |

| 14/F | AML CNS+ (FLT3-ITD+) | Chemo + sorafenib + Haplo HSCT | CR, OS: 8+ m | [41] |

| 42/M | MDS/AML (−7, 19p Abn, RUNX1+, KRAS+, PTPN11+) | Azacitidine, Decitabine, Chemo, Haplo HSCT | CR after Haplo, OS: 6+ m | [42] |

| 19/M | Ph+ ALL | Chemo + imatinib | OS: 6 m (meningoencephalitis) | [43] |

| 31/F | AML0 (−7, 11p−, WT1+, RUNX1+, PTPN11+) | Chemo + Haplo HSCT | CR (MRD+), OS: 12 m (AML progression) | [44] |

| 40/M | MDS (complex cytogenetics, 5q−, 3p, 7p, −16, −7, −18) | None | OS: 3 m (severe cytopenia) | [45] |

| 27/F | MDS/AML (−3, t5;7, −7, del12, −22, TP53+) | Vyxeos, MEC, HSCT | CR, MRD− after HSCT, OS: 12+ m | [46] |

| 48/F | AML3 | Chemo + ATRA + arsenic trioxide | CR, MRD− | [47] |

| Patient/Diagnosis/Origin | Age at Diagnosis | Treatment | Clinical Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS/Afr.Am | NA | No HU | NA | [16] |

| SS/NA | Infancy | Transfusions | NA | [17] |

| SS/NA | NA | Transfusions | Hemosiderosis | [18] |

| SS/Afr.Am | Infancy | NA | NA | [19] |

| SS/NA | At birth | NA | NA | [20] |

| SC/Afr.Am | NA | NA | Aseptic necrosis humeral head | [21] |

| SS/Nigerian | NA | NA | NA | [22] |

| SS/Afr.Am | Infancy | No HU | VOC | [23] |

| SS/NA | Infancy | HU (1.5 months) | VOC (3–7/year) | [24] |

| SS/NA | NA | HU (8 years) | VOC | [25] |

| SS/NA | NA | HU (6 years) | NA | [26] |

| SS/Saudi | NA | HU (2 years) | VOC (6/year), hepatitis C | [27] |

| SS/NA | Infancy | HU (3 months) | NA | [10] |

| SS/NA | Infancy | No HU | NA | |

| SS/NA | Infancy | No HU | NA | |

| SS/NA | Infancy | No HU, HSCT | NA | |

| SS/NA | Infancy | No HU | NA | |

| SS/NA | NA | No HU | NA | |

| SS/NA | NA | No HU | NA | |

| SS/NA | NA | No HU | NA | |

| SS/NA | NA | HU (8 years) | VOC, osteonecrosis, ACS | [28] |

| SS/Afr.Am | NA | HU (5 years), transfusions | VOC, priapism, ACS | [29] |

| SS/Afr.Am | 21 | Exchange transfusions, HU (15 years) | VOC (14 to 3/year) | [30] |

| SS/Jamaican | NA | No HU | Pulmonary hypertension | [31] |

| SS/NA | NA | HU (14 years), transfusions | VOC, hip necrosis, retinopathy, stroke, iron overload | [32] |

| SS/Indian | NA | Transfusions, HU | NA | [33] |

| SS/Indian | NA | HU | NA | |

| SS/Afr.Am | Childhood | HU (5 years), Haplo HSCT (8 months) | VOC | [34] |

| SC/NA | NA | HU, exchange transfusions | HHV8 | [35] |

| SS/NA | NA | Exchange transfusions | VOC, myocardial infarction, HIV+ | |

| SS/NA | Infancy | Exchange transfusions | VOC | |

| Sβ0/NA | NA | Exchange transfusions, HU (9 years) matched HSCT (7 years) | VOC, priapism, arterial aneurysm, intracranial bleeding | |

| NA/NA | NA | Haplo HSCT (3.6 years) | NA | * [36] |

| NA/NA | NA | Haplo HSCT (9 months) | NA | |

| NA/NA | NA | Haplo HSCT (1 year) | NA | |

| NA/NA | NA | Matched sibling HSCT (2.6 years) | NA | |

| SS/Afr.Am | Childhood | Transfusion/exchange HU (2 years) | VOC, pulmonary fibrosis, pneumonia, hip necrosis, peritonitis | [37] |

| SS/Nigerian | 2 years | No HU, transfusion | VOC (2/year) | [38] |

| SS/Nigerian | 4 years | No HU | VOC (1/year) | |

| SC/Nigerian | Childhood | No HU | VOC (once in 2–3 years) | |

| SC/Nigerian | NA | No HU | None | |

| SS/Nigerian | NA | No HU, transfusions | NA | |

| SS/NA | NA | HU (5 years) | VOC | [39] |

| SS/NA | NA | HU, Haplo HSCT (2 years) | Stroke, CRI, VOC | [40] |

| SS/NA | NA | HU, sibling HSCT (2.5 years) | VOC | |

| SS/NA | NA | HU, Haplo HSCT (5 years) | Diastolic dysfunction, ESRD, pulmonary hypertension | |

| Sβ0/Haitian | At birth | HU (9 years) | VOC | [41] |

| SS/NA | NA | HU (8 years), gene therapy | VOC, iron overload, hypertension | [42] |

| SS/Nigerian | At 1 year | Transfusions, no HU | VOC (>4/year) | [43] |

| SS/NA | NA | HU (6 years), gene therapy (LentiGlobin) (5.5 years) | VOC, hip necrosis, deep-vein thrombosis | [44] |

| SS/NA | NA | HU (17 years), exchange transfusions | VOC, priapism, pulmonary hypertension | [45] |

| Sβ0/African | Childhood | HU (7 years), exchange transfusions | VOC, ACS, retinopathy, cholelithiasis, COVID 19 | [46] |

| SD/NA | NA | No HU, transfusions | Hemolytic crisis, bone osteonecrosis and sclerosis, ACS | [47] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casadessus, E.; Saby, M.; Forté, S.; Pastore, Y.; Lavallée, V.-P.; Pincez, T. When Blood Disorders Meet Cancer: Uncovering the Oncogenic Landscape of Sickle Cell Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8509. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238509

Casadessus E, Saby M, Forté S, Pastore Y, Lavallée V-P, Pincez T. When Blood Disorders Meet Cancer: Uncovering the Oncogenic Landscape of Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8509. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238509

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasadessus, Elise, Manon Saby, Stéphanie Forté, Yves Pastore, Vincent-Philippe Lavallée, and Thomas Pincez. 2025. "When Blood Disorders Meet Cancer: Uncovering the Oncogenic Landscape of Sickle Cell Disease" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8509. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238509

APA StyleCasadessus, E., Saby, M., Forté, S., Pastore, Y., Lavallée, V.-P., & Pincez, T. (2025). When Blood Disorders Meet Cancer: Uncovering the Oncogenic Landscape of Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8509. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238509