Patient Blood Management in Hematology: Focusing on Platelet Transfusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Evaluation of the Platelet Transfusion Practice in Hematological Patients of a Tertiary Care Center

2.2. Intervention: Development of Specific Platelet Transfusion Guidelines for Hematological Patients

2.3. Monitoring the Impact of Intervention Follow-Up

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Platelet Transfusion Audit in Inpatient and Outpatient Settings

3.2. Platelet Transfusion Audit in Specific Procedures

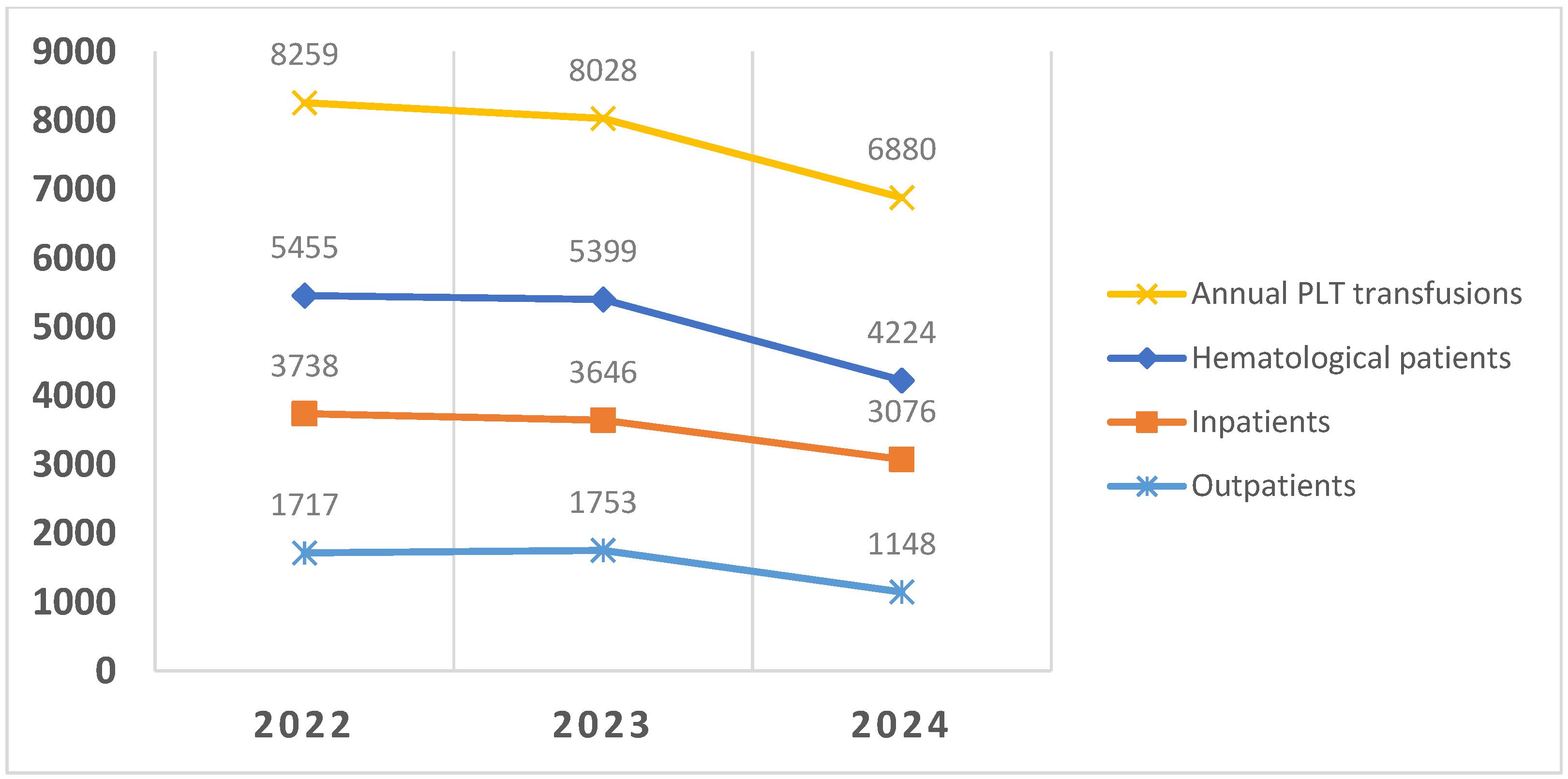

3.3. Platelet Transfusion Activity

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PBM | Patient blood management |

| PLT | Platelets |

References

- Mo, A.; Wood, E.; McQuilten, Z. Platelet transfusion. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2025, 32, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SISNT. Actividad Centros y Servicios de Transfusion. Sistema Nacional Para la Seguridad Transfusional SNST. 2023. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/medicinaTransfusional/publicaciones/docs/Informe_Actividad2023.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Annen, K.; Olson, J.E. Optimizing platelet transfusions. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2015, 22, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facco, G.; Bennardello, F.; Fiorin, F.; Galassi, C.; Monagheddu, C.; Berti, P. A nationwide survey of clinical use of blood in Italy. Blood Transfus. 2021, 19, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Estcourt, L.J.; Birchall, J.; Allard, S.; Bassey, S.J.; Hersey, P.; Kerr, J.P.; Mumford, A.D.; Stanworth, S.J.; Tinegate, H. Guidelines for the use of platelet transfusions. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 176, 365–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalf, R.A.; Nahirniak, S.; Guyatt, G.; Bathla, A.; White, S.K.; Al-Riyami, A.Z.; Jug, R.C.; La Rocca, U.; Callum, J.L.; Cohn, C.S.; et al. Platelet Transfusion: 2025 AABB and ICTMG International Clinical Practice Guidelines. JAMA 2025, 334, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solves Alcaina, P. Platelet Transfusion: And Update on Challenges and Outcomes. J. Blood Med. 2020, 11, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedhom, R.; Willett, L. Do Physicians Adhere to Platelet Transfusion Guidelines? Am. J. Med. Qual. 2016, 31, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill-Strathy, M.; Pinkerton, P.H.; Thompson, T.A.; Wendt, A.; Collins, A.; Cohen, R.; Bcomm, W.O.; Cameron, T.; Lin, Y.; Lau, W.; et al. Evaluating the appropriateness of platelet transfusions compared with evidence-based platelet guidelines: An audit of platelet transfusions at 57 hospitals. Transfusion 2021, 61, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solves, P.; Moscardo, F.; Lancharro, A.; Cano, I.; Carpio, N.; Sanz, M.Á. A retrospective audit of platelet transfusion in a hematology service of a tertiary-care hospital: Effectiveness of training to improve compliance with standards. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2014, 50, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhrkuhl, D.C.; Karlsson, M.K.P.; Carter, J.M. An audit of platelet transfusion within the Wellington Cancer Centre. Intern. Med. J. 2012, 42, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehrie, E.A.; Young, P.P.; Basavaraju, S.V.; Bracey, A.W.; Cap, A.P.; Culler, L.; Dunbar, N.M.; Homer, M.; Isufi, I.; Macedo, R.; et al. Addressing platelet insecurity—A national call to action. Transfusion 2024, 64, 2001–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhar, M.; Clark, S.; Atugonza, R.; Li, A.; Chaudhry, Z. Effective implementation of a patient blood management programme for platelets. Transfus. Med. 2016, 26, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, R.M.; Djulbegovic, B.; Gernsheimer, T.; Kleinman, S.; Tinmouth, A.T.; Capocelli, K.E.; Cipolle, M.D.; Cohn, C.S.; Fung, M.K.; Grossman, B.J.; et al. Platelet transfusion: A clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenna, D.; Shastry, S.; Baliga, P. Use of platelet components: An observational audit at a tertiary care centre. Natl. Med. J. India 2021, 34, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.; Bakhtary, S.; Benson, K.; Stephens, L.; Lu, W. A National Survey of Outpatient Platelet Transfusion Practice. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2022, 158, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandt, H.; Schaefer-Eckart, K.; Wendelin, K.; Pilz, B.; Wilhelm, M.; Thalheimer, M.; Mahlknecht, U.; Ho, A.; Schaich, M.; Kramer, M.; et al. Therapeutic platelet transfusion versus Routine prophylactic transfusion in patients with haematological malignancies: An open-label, multicentre, randomised study. Lancet 2012, 380, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthon, C.T.; Granholm, A.; Sivapalan, P.; Zellweger, N.; Pène, F.; Puxty, K.; Perner, A.; Møller, M.H.; Russell, L. Prophylactic platelet transfusions versus no prophylaxis in hospitalized patients with thrombocytopenia: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Transfusion 2022, 62, 2117–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnanaraj, J.; Basavarajegowda, A.; Kayal, S.; Sahoo, D.; Toora, E.; Dubashi, B.; Ganesan, P. Optimising platelet usage during the induction therapy of acute myeloid leukaemia: Impact of physician education. Transfus. Med. 2023, 33, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Favaloro, E.J.; Buoro, S. Platelet Transfusion Thresholds: How Low Can We Go in Respect to Platelet Counting? Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 46, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Situation (Inpatients and Outpatients) | Platelet Threshold |

|---|---|

| Prophylactic use | <10,000/µL |

| Prophylactic use with additional risk factors (fever, sepsis, coagulopathy) | <20,000/µL |

| Acute promyelocytic leukemia | <30,000/µl |

| Bleeding | <50,000/µL |

| Multiple trauma or CNS injury/bleeding | <100,000/µL |

| Pre-procedure | |

| Major surgery | <50,000/µL |

| Bronchoscopy/liver biopsy | <50,000/µL |

| Lumbar puncture | <40,000/µL |

| Insertion of central venous catheter | <50,000/µL |

| insertion/removal of epidural catheter | <80,000/µL |

| Audit 1 (2022–2023) | Audit (2024–2025) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 128 | 130 | |

| Platelet transfusion episodes (n) | 288 | 315 | |

| Prophylactic transfusions (n) Pre-transfusion count Appropriate (%) | 245 11,000 (1000–47,000) 135 (55%) | 279 9000 (1000–74,000) 211 (75.6%) | 0.151 <0.001 |

| Pre-procedure transfusions (n) Pre-transfusion count/µL Appropriate (%) | 12 24,000 (15,000–45,000) 7 (58.3%) | 33 21,000 (3000–67,000) 33 (100%) | 0.222 0.006 |

| Therapeutic transfusions Pre-transfusion count/µL Appropriate (%) | 25 27,000 (2000–52,000) 22 (88%) | 42 26,500 (4000–104,000) 36 (85.7%) | 0.810 0.564 |

| Audit 1 (2022–2023) | Audit 2 (2024–2025) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 49 | 45 | |

| Platelet transfusion episodes (n) | 164 | 148 | |

| Prophylactic transfusions (n) Pre-transfusion count/µL Appropriate (%) | 154 11,000 (2000–35,000) 71 (46%) | 125 10,000 (2000–160,000) 69 (54.3%) | 0.396 0.332 |

| Pre-procedure transfusions (n) Pre-transfusion count/µL Appropriate (%) | 8 (1, 2, 4 and 5) 19,000 (7000–40,000) 2 (25%) | 4 (1, 2, 3) 52,000 (13,000–65,000) 2 (50%) | 0.109 0.648 |

| Therapeutic transfusions Pre-transfusion count Appropriate (%) | 2 25,000 (25,000–29,000) 2 (100%) | 19 16,000 (3000–55,000) 10 (52.6%) | 0.218 0.293 |

| Bone Marrow Aspirate or Trephine Biopsy | Lumbar Puncture | Bronchoscopy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients reviewed | 123 | 98 | 107 |

| Patients transfused (n) Platelet count/µL | 17 13,000 (4000–42,000) | 47 34,000 (8000–105,000) | 62 39,000 (3000–88,000) |

| Transfused 1 PC * (n) Platelet count/µL | All | 26 74,000 (21,000–105,000) | 31 41,000 (10,000–88,000) |

| Transfused 2 PC (n) Platelet count/µl | 0 | 21 34,000 (8000–105,000) | 31 36,000 (3000–49,000) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solves, P.; Córcoles, M.; Soriano, M.; Lamas, B.; Martínez-Campuzano, D.; Asensi, P.; Gómez-Seguí, I.; de la Rubia, J. Patient Blood Management in Hematology: Focusing on Platelet Transfusion. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238434

Solves P, Córcoles M, Soriano M, Lamas B, Martínez-Campuzano D, Asensi P, Gómez-Seguí I, de la Rubia J. Patient Blood Management in Hematology: Focusing on Platelet Transfusion. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238434

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolves, Pilar, Micaela Córcoles, Montiel Soriano, Brais Lamas, David Martínez-Campuzano, Pedro Asensi, Inés Gómez-Seguí, and Javier de la Rubia. 2025. "Patient Blood Management in Hematology: Focusing on Platelet Transfusion" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238434

APA StyleSolves, P., Córcoles, M., Soriano, M., Lamas, B., Martínez-Campuzano, D., Asensi, P., Gómez-Seguí, I., & de la Rubia, J. (2025). Patient Blood Management in Hematology: Focusing on Platelet Transfusion. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238434