Depression and Anxiety During Pregnancy in Mexican Women: Prevalence and Associated Factors in the OBESO Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

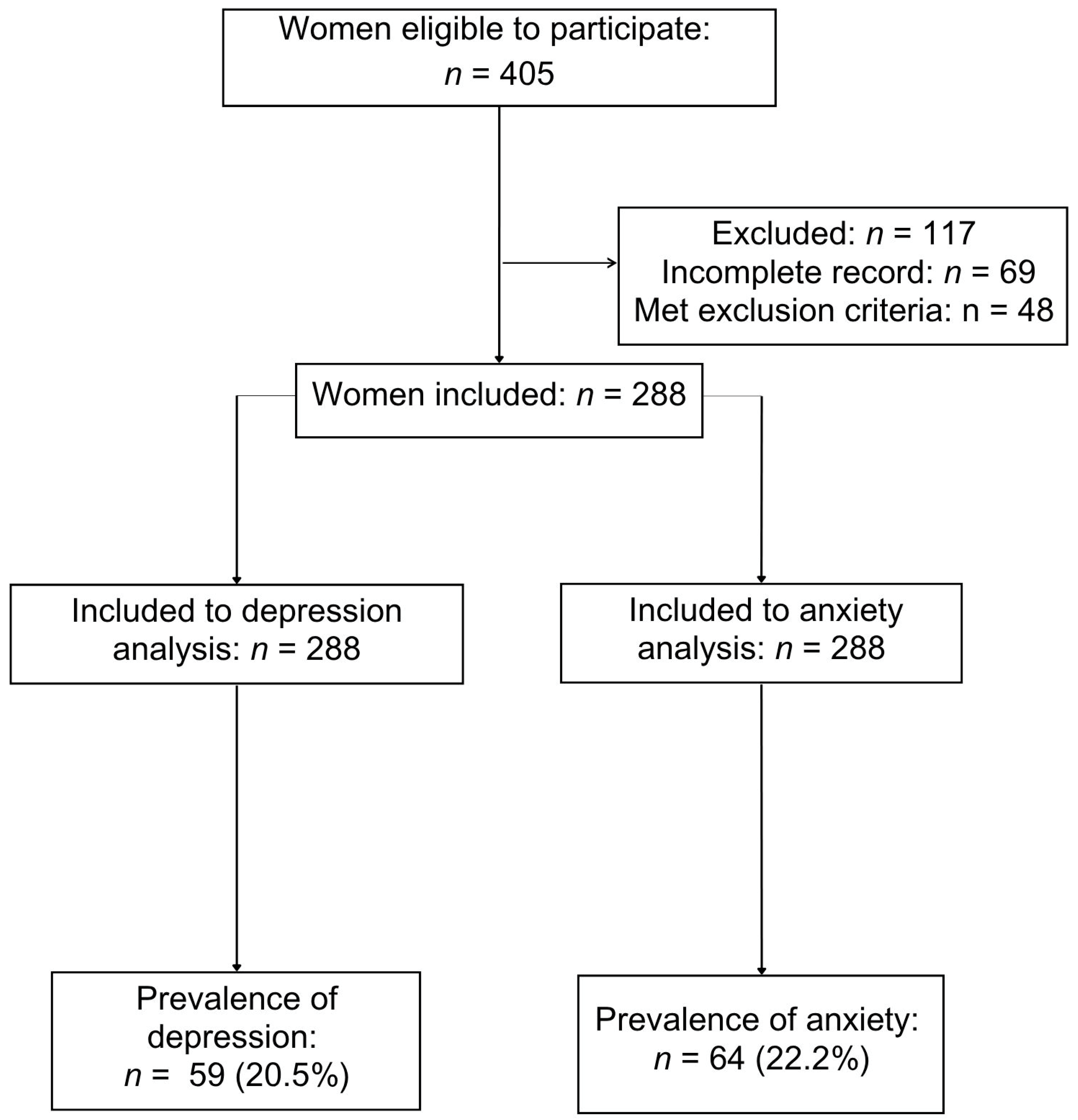

2.2. Participants and Procedures

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

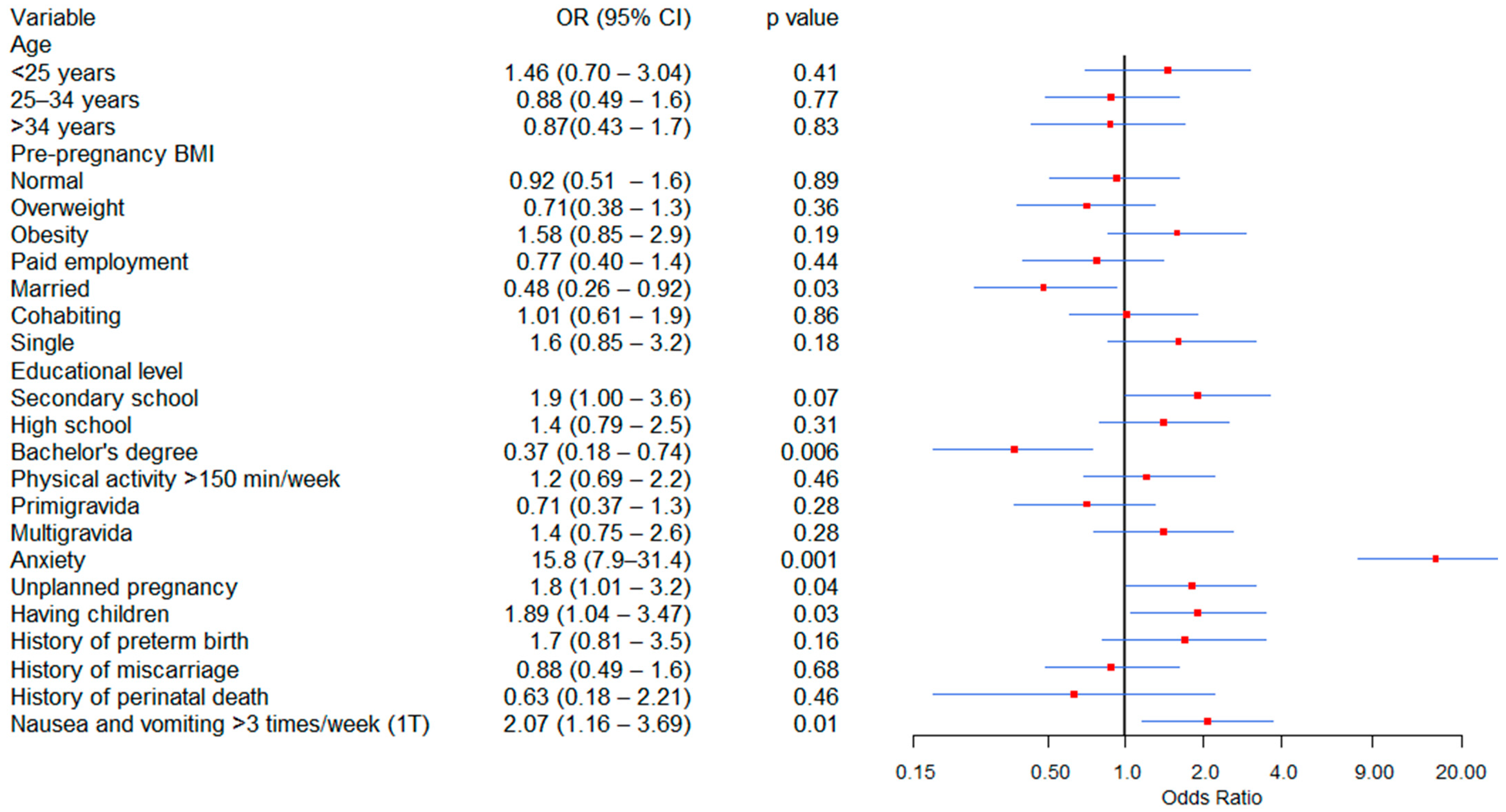

3.2. Factors Associated with Depression

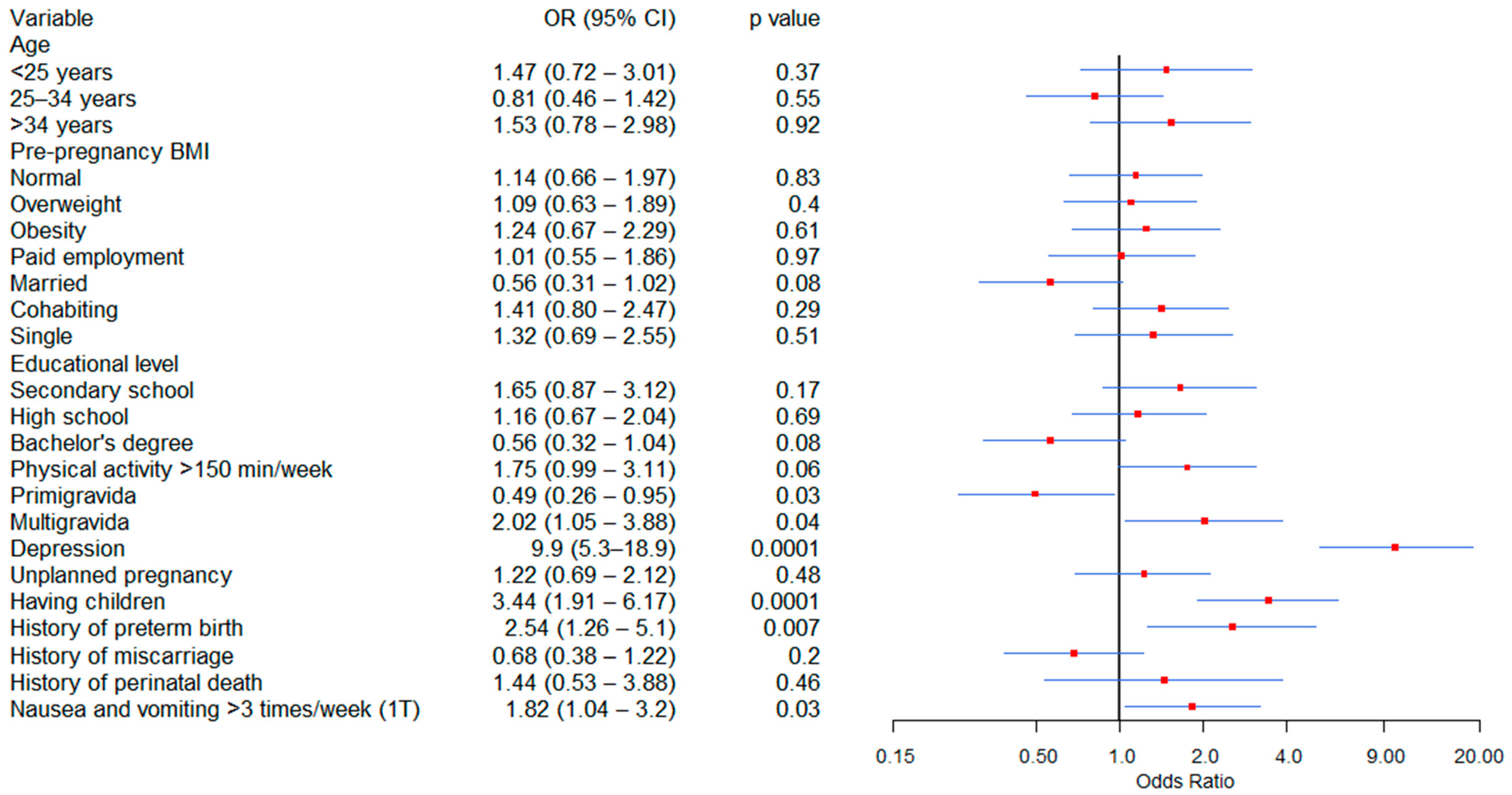

3.3. Factors Associated with Anxiety

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Comparison with Existing Literature

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OBESO | Biochemical and Epigenetic Origins of Overweight and Obesity |

| INPerIER | National Institute of Perinatology Isidro Espinosa de los Reyes |

| EPDS | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) |

References

- Redinger, S.; Norris, S.A.; Pearson, R.M.; Richter, L.; Rochat, T. First Trimester Antenatal Depression and Anxiety: Prevalence and Associated Factors in an Urban Population in Soweto, South Africa. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2018, 9, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, U.; Papabathini, S.S.; Kawuki, J.; Obore, N.; Musa, T.H. Depression during Pregnancy and the Risk of Low Birth Weight, Preterm Birth and Intrauterine Growth Restriction—An Updated Meta-Analysis. Early Hum. Dev. 2021, 152, 105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korja, R.; Nolvi, S.; Scheinin, N.M.; Tervahartiala, K.; Carter, A.; Karlsson, H.; Kataja, E.-L.; Karlsson, L. Trajectories of Maternal Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms and Child’s Socio-Emotional Outcome during Early Childhood. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 349, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downes, N.; Kallas, K.-A.; Moirangthem, S.; Maguet, C.; Marr, K.; Tafflet, M.; Kirschbaum, C.; Heude, B.; Koehl, M.; van der Waerden, J. Longitudinal Effects of Maternal Depressive and Anxious Symptomatology on Child Hair Cortisol and Cortisone from Pregnancy to 5-Years: The EDEN Mother-Child Cohort. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2024, 162, 106957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarde, A.; Morais, M.; Kingston, D.; Giallo, R.; MacQueen, G.M.; Giglia, L.; Beyene, J.; Wang, Y.; McDonald, S.D. Neonatal Outcomes in Women With Untreated Antenatal Depression Compared with Women Without Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Míguez, M.C.; Vázquez, M.B. Risk Factors for Antenatal Depression: A Review. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.J.; Van Zanden, B.; Galbally, M. Fetal Exposures and Maternal Mental Disorders in Pregnancy: A Network Analysis. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2025, 16, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, S.J.; Lewis, A.J.; Boyce, P.; Galbally, M. Exercise Frequency and Maternal Mental Health: Parallel Process Modelling across the Perinatal Period in an Australian Pregnancy Cohort. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 111, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Lo-Ciganic, W.-H.; Segal, R.; Goodin, A.J. Prevalence of Substance Use Disorder and Psychiatric Comorbidity Burden among Pregnant Women with Opioid Use Disorder in a Large Administrative Database, 2009–2014. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 42, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengaud, J.B.; Yzydorczyk, C.; Siddeek, B.; Peyter, A.C.; Simeoni, U. Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Clinical Consequences on Health and Disease at Adulthood. Reprod. Toxicol. 2021, 99, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, E.; Hor, K.; Drake, A.J. Maternal Influences on Fetal Brain Development: The Role of Nutrition, Infection and Stress, and the Potential for Intergenerational Consequences. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 150, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roddy Mitchell, A.; Gordon, H.; Atkinson, J.; Lindquist, A.; Walker, S.P.; Middleton, A.; Tong, S.; Hastie, R. Prevalence of Perinatal Anxiety and Related Disorders in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2343711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen-Scott, M.; Fellmeth, G.; Opondo, C.; Alderdice, F. Prevalence of Perinatal Anxiety in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 306, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddy Mitchell, A.; Gordon, H.; Lindquist, A.; Walker, S.P.; Homer, C.S.E.; Middleton, A.; Cluver, C.A.; Tong, S.; Hastie, R. Prevalence of Perinatal Depression in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.; Obst, S.; Teague, S.J.; Rossen, L.; Spry, E.A.; Macdonald, J.A.; Sunderland, M.; Olsson, C.A.; Youssef, G.; Hutchinson, D. Association Between Maternal Perinatal Depression and Anxiety and Child and Adolescent Development: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 1082–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delagneau, G.; Twilhaar, E.S.; Testa, R.; van Veen, S.; Anderson, P. Association between Prenatal Maternal Anxiety And/or Stress and Offspring’s Cognitive Functioning: A Meta-Analysis. Child Dev. 2023, 94, 779–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, K.S.; Camilo, C.; Gouveia, G.; Euclydes, V.; Panter-Brick, C.; Matijasevich, A.; Ferraro, A.A.; Fracolli, L.A.; Chiesa, A.M.; Miguel, E.C.; et al. Maternal Distress, DNA Methylation, and Fetal Programing of Stress Physiology in Brazilian Mother-Infant Pairs. Dev. Psychobiol. 2023, 65, e22352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.M.; Bornstein, M.H.; Cordero, M.; Scerif, G.; Mahedy, L.; Evans, J.; Abioye, A.; Stein, A. Maternal Perinatal Mental Health and Offspring Academic Achievement at Age 16: The Mediating Role of Childhood Executive Function. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Melotti, R.; Heron, J.; Ramchandani, P.; Wiles, N.; Murray, L.; Stein, A. The Timing of Maternal Depressive Symptoms and Child Cognitive Development: A Longitudinal Study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, V.J.; de Vries, E.; van Baar, A.L.; Waelkens, J.J.; de Rooy, H.A.; Horsten, M.; Donkers, M.M.; Komproe, I.H.; van Son, M.M.; Vader, H.L. Maternal Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies during Pregnancy: A Marker of Impaired Child Development? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995, 80, 3561–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez Padilla, J.; Lara-Cinisomo, S.; Navarrete, L.; Lara, M.A. Perinatal Anxiety Symptoms: Rates and Risk Factors in Mexican Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Lu, Z.; Hu, D.; Zhong, X. Influencing Factors for Prenatal Stress, Anxiety and Depression in Early Pregnancy among Women in Chongqing, China. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanwetswinkel, F.; Bruffaerts, R.; Arif, U.; Hompes, T. The Longitudinal Course of Depressive Symptoms during the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 315, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of Postnatal Depression. Development of the 10-Item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. STAI Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (“Self-Evaluation Questionnaire”); Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Quijano, M.E.; Córdova, A.; Contreras-Ramírez, V.; Farias-Hernández, L.; Cruz Tolentino, M.; Casanueva, E. Risk for Postpartum Depression, Breastfeeding Practices, and Mammary Gland Permeability. J. Hum. Lact. 2008, 24, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Rico, B.V.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Sánchez-Martínez, M.; Perichart-Perera, O.; Rodríguez-Hernández, C.; González-Leyva, C.; Osorio-Valencia, E.; Cardona-Pérez, A.; Helguera-Repetto, A.C.; Espino, Y.; et al. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Perceived Stress in Postpartum Mexican Women during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Diaz-Guerrero, R. IDARE Inventario de Ansiedad: Rasgo-Estado; Manual Moderno: Mexico City, Mexico, 1975; ISBN 9789684268630. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C.-L.; Coghlan, M.; Vigod, S. Can We Identify Mothers at-Risk for Postpartum Anxiety in the Immediate Postpartum Period Using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory? J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 150, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, N.; Eberhard-Gran, M.; Sletner, L.; Slinning, K.; Martinsen, E.W.; Holme, I.; Jenum, A.K. A Prospective Cohort Study of Depression in Pregnancy, Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Multi-Ethnic Population. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wu, J.; Chen, X. Risk Factors of Perinatal Depression in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, T.; Zeng, Y.; Chai, X.; Wen, Z.; Tan, X.; Sun, M. Global Prevalence of Perinatal Depression and Its Determinants Among Rural Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2024, 2024, 1882604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Sun, N.; Jiang, N.; Xu, X.; Gan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, L.; Yang, C.; Shi, X.; Chang, J.; et al. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Antenatal Depression: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 83, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, S.T.A.; Yeasar, S.; Siddique, S.; Banik, R.; Raza, S. Prevalence, Determinants and Wealth-Related Inequality of Anxiety and Depression Symptoms Among Reproductive-Aged Women (15–49 Years) in Nepal: An Analysis of Nationally Representative Nepal Demographic and Health Survey Data 2022. Depress. Anxiety 2025, 2025, 9942669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, N.; Robakis, T.; Miller, C.; Butwick, A. Prevalence of Depression Among Women of Reproductive Age in the United States. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Participants n = 288 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.2 ± 5.2 |

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index | 27.6 ± 5.4 |

| Gestational age at enrollment (weeks) | 13.0 ± 0.6 |

| Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale | 7.3 ± 6.1 |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | 34.4 ± 10.2 |

| Educational level | |

| Secondary school | 61 (21.1%) |

| High school | 122 (42.4%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 105 (36.5%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 114 (39.6%) |

| Cohabiting | 112 (38.9%) |

| Single | 62 (21.5%) |

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index | |

| Normal (18.5–24.99 kg/m2) | 107 (37.2%) |

| Overweight (25–29.99 kg/m2) | 106 (36.8%) |

| Obesity (≥30 kg/m2) | 75 (26.0%) |

| Variable | Beta | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Married | −0.624 | 0.21 | 0.53 (0.20–1.41) |

| Single | 0.624 | 0.21 | 1.86 (0.71–4.91) |

| Secondary and high school | 0.957 | 0.03 | 2.60 (1.10–6.14) |

| Bachelor’s degree | −0.957 | 0.03 | 0.38 (0.16–0.90) |

| Anxiety | 2.394 | 0.0001 | 10.8 (5.4–21.6) |

| Unplanned pregnancy | 0.493 | 0.207 | 1.63 (0.76–3.52) |

| Having children | 0.059 | 0.89 | 1.06 (0.45–2.45) |

| Nausea and vomiting > 3 times/week (1T) | 0.444 | 0.25 | 1.55 (0.72–3.35) |

| Variable | Beta | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity > 150 min/week | 410 | 0.24 | 1.51 (0.75–2.77) |

| Primigravida | −0.041 | 0.93 | 0.96 (0.35–2.62) |

| Multigravida | 0.041 | 0.93 | 1.04 (0.75–3.01) |

| Depression | 2.351 | 0.0001 | 11.2 (5.6–22.1) |

| Having children | 0.956 | 0.03 | 3.1 (1.60–6.10) |

| History of preterm birth | 0.434 | 0.35 | 1.54 (0.62–3.84) |

| Nausea and vomiting > 3 times/week (1T) | 0.333 | 0.34 | 1.39 (0.70–2.77) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suárez-Rico, B.V.; González-Ludlow, I.; Mendoza-Ortega, J.A.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; de Abiega-Franyutti, P.; Espino y Sosa, S.; Hernández-Chávez, M.d.C.; Osorio-Valencia, E.; Gil-Martínez, G.; Montoya-Estrada, A.; et al. Depression and Anxiety During Pregnancy in Mexican Women: Prevalence and Associated Factors in the OBESO Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8364. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238364

Suárez-Rico BV, González-Ludlow I, Mendoza-Ortega JA, Estrada-Gutierrez G, de Abiega-Franyutti P, Espino y Sosa S, Hernández-Chávez MdC, Osorio-Valencia E, Gil-Martínez G, Montoya-Estrada A, et al. Depression and Anxiety During Pregnancy in Mexican Women: Prevalence and Associated Factors in the OBESO Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8364. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238364

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuárez-Rico, Blanca Vianey, Isabel González-Ludlow, Jonatan Alejandro Mendoza-Ortega, Guadalupe Estrada-Gutierrez, Pilar de Abiega-Franyutti, Salvador Espino y Sosa, Maria del Carmen Hernández-Chávez, Erika Osorio-Valencia, Gabriela Gil-Martínez, Araceli Montoya-Estrada, and et al. 2025. "Depression and Anxiety During Pregnancy in Mexican Women: Prevalence and Associated Factors in the OBESO Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8364. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238364

APA StyleSuárez-Rico, B. V., González-Ludlow, I., Mendoza-Ortega, J. A., Estrada-Gutierrez, G., de Abiega-Franyutti, P., Espino y Sosa, S., Hernández-Chávez, M. d. C., Osorio-Valencia, E., Gil-Martínez, G., Montoya-Estrada, A., Romo-Yañez, J., Camacho-Arroyo, I., Perichart-Perera, O., & Reyes-Muñoz, E. (2025). Depression and Anxiety During Pregnancy in Mexican Women: Prevalence and Associated Factors in the OBESO Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8364. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238364