Proposed Clinical Practice Guidance for Large-Volume Abdominal and Pleural Paracentesis with Emphasis on Coagulopathy Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

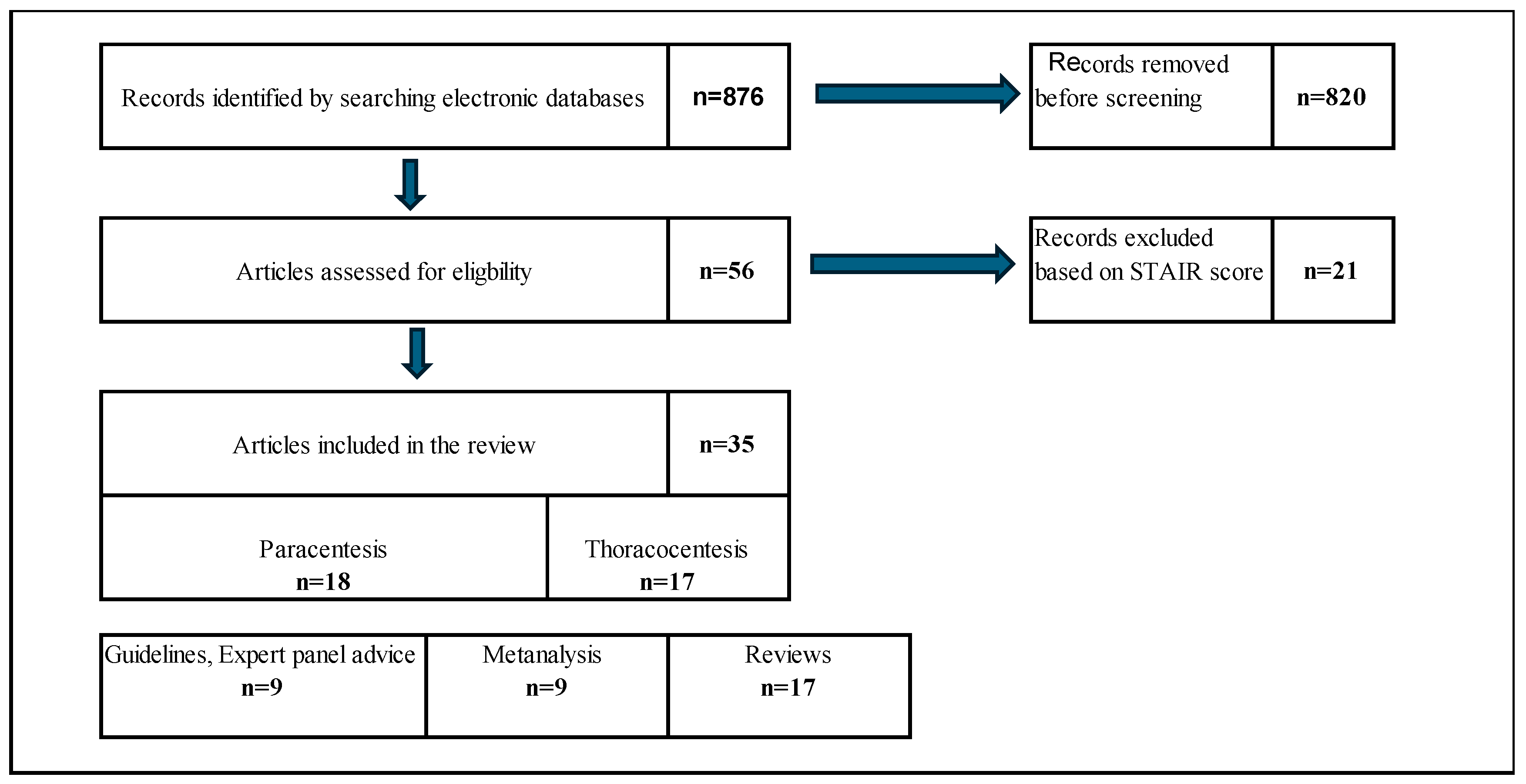

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Study Selection and Appraisal

2.3. Results of Literature Screening

3. Section I: Abdominal Paracentesis in Patients with Ascites

3.1. Indications [1,2,3,4]

- Diagnostic assessment: Evaluation of ascitic fluid characteristics, including determination of the serum–ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) to distinguish high (>1.1 g/dL) versus low (<1.1 g/dL) SAAG ascites.

- Evaluation for infection or malignant transformation:

- ○

- Rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP).

- ○

- Assess for suspected hepatocellular carcinoma–related malignant ascites.

- Symptomatic ascites, such as tense ascites causing respiratory compromise or abdominal discomfort

- Refractory ascites requiring repeated therapeutic drainage

3.2. Clinical Suggestions for Peritoneal Paracentesis

3.3. Major Complications [3,4,5,6,7,17]

- Hemorrhage (0.3–1%) [3,6]: The incidence of hemorrhage is reduced by 50% with ultrasound (US) guidance [8]. Bleeding during paracentesis typically results from an injury to a branch of the inferior epigastric artery of the abdominal wall. Bleeding can occur in two ways.

- Gradual increase in bleeding during the procedure. In such instances, the drainage initially appears serous and progressively becomes hemorrhagic. This suggests arterial bleeding into the peritoneal cavity surrounding the catheter, which leads to increasingly bloody fluid.

- Bowel perforation: This recognized but rare complication occurred in <1% of patients in a large series of diagnostic paracenteses. The risk is higher in patients with intra-abdominal adhesions, prior abdominal surgery, or distorted anatomy due to underlying disease [11,12]. Clinically, bowel perforation may present acutely with the return of fecal material; gas through the paracentesis catheter; or more insidiously with signs of peritonitis, sepsis, or polymicrobial peritoneal infection. Immediate recognition is critical as delayed diagnosis increases peritonitis and sepsis risks. Management depends on the clinical scenario. Stable patients without peritonitis may be managed conservatively with bowel rest and broad-spectrum antibiotics; however, surgical intervention is indicated for patients with generalized peritonitis or clinical deterioration [12,19]. To minimize risk, the needle should be inserted at sites with the lowest likelihood of underlying bowel, such as the left lower quadrant lateral to the rectus abdominis or the midline 2 cm below the umbilicus, and never through surgical scars or areas with suspected adhesions [20].

- SBP during peritoneal paracentesis refers to a peritoneal infection that arises from a direct, identifiable intra-abdominal source that disrupts the integrity of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts. Secondary peritonitis is typically polymicrobial, involving both aerobic and anaerobic organisms, most commonly Gram-negative rods (such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp.), anaerobes (such as Bacteroides spp. and Clostridium spp.), and Gram-positive cocci (such as Enterococcus spp.). The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology emphasize that, in contrast to SBP, secondary peritonitis is usually polymicrobial and may include anaerobic microbiota, and that peritoneal fluid should be sent for both aerobic and anaerobic cultures in an anaerobic transport system [19]. Diagnosis during paracentesis is suggested by the presence of multiple organisms on Gram staining or culture, elevated ascitic fluid neutrophil count, and biochemical features such as low glucose, high lactate dehydrogenase, and low protein levels. Clinical suspicion should be high in patients with severe abdominal symptoms or evidence of sepsis. Imaging (e.g., computed tomography) is often required to identify the source [20]. Management requires the prompt administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics covering both aerobic and anaerobic organisms and urgent surgical or interventional radiology evaluation to control the infection source, as medical therapy alone is insufficient. Without timely intervention, mortality is high [20,21].

- Post-paracentesis circulatory dysfunction (PICD) manifests as effective hypovolemia and renal impairment, usually after the removal of >5 L. The American College of Radiology states that PICD can develop in up to 80% of patients with cirrhosis if volume expansion (typically using albumin) is not performed at the time of paracentesis. The pathophysiology involves a rapid drop in intra-abdominal pressure, leading to increased venous return, transiently increased cardiac output, and subsequent activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone and sympathetic nervous systems, resulting in decreased effective arterial blood volume and free water retention [22].

- Puncture site leakage following large-volume peritoneal paracentesis is a recognized complication, with reported rates varying from 0% to 23% [12]. The primary cause is persistent ascitic fluid flow through the needle tract, which may be exacerbated by high intra-abdominal pressure, large-volume removal, or technical failure of sealing the skin and subcutaneous tissues after catheter removal. The initial management options include conservative measures [12]. The first-line approach involves the application of a pressure dressing directly over the puncture site, which is effective in most cases. The use of the Z-tract technique during the procedure, in which the skin is displaced before needle insertion to create a zigzag tract, may help prevent leakage, although evidence for its efficacy is limited. If leakage persists, additional options include continued pressure dressings, use of ostomy appliances to collect fluid, or, rarely, placement of a suture at the site [12]. Rarely, persistent or high-volume leaks may require further intervention such as peritoneal drains or surgical closure. Infection should be ruled out if the leak is prolonged or is associated with local erythema.

4. Section II: Thoracocentesis in Patients with Pleural Effusion

4.1. Indications [8,23,24,25]

- New or unexplained pleural effusion, to differentiate between transudate and exudate based on Light’s criteria

- Suspected infection (empyema or parapneumonic effusion), especially if the effusion is loculated or shows signs of sepsis

- Suspected malignancy, particularly in patients with cancer history or unilateral/bloody effusions

- Suspected tuberculous pleuritis based on the regional epidemiology and clinical presentation

- Symptomatic relief of dyspnea, especially in patients with large pleural effusions causing lung compression and impaired ventilation. This indication is common in malignant effusion, heart failure, or hepatic hydrothorax

- Large effusion with signs of respiratory compromise such as tachypnea, hypoxemia, or use of accessory muscles

- Effusion refractory to medical management; for example: diuretic-resistant pleural effusions in CHF

- Recurrent malignant pleural effusion requiring repeated drainage as a bridge to pleurodesis or indwelling pleural catheter placement

4.2. Clinical Suggestions for Thoracocentesis

4.3. Complications

- Re-expansion pulmonary edema: This is a rare but potentially serious complication, with an incidence of <0.1%, and is associated with rapid or large-volume fluid removal, especially if pleural pressures fall below −20 cm H2O or if >1.5 L is removed quickly. Symptom-limited drainage is recommended to mitigate this risk [5].

- Secondary infections: Complications following thoracentesis include empyema (pus in the pleural space), parapneumonic effusion (infected pleural fluid associated with pneumonia), and, less commonly, cellulitis or soft tissue infection at the puncture site. These complications are rare when sterile technique is used. Empyema and complicated parapneumonic effusion are clinically significant and often require antimicrobial therapy and drainage. According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology, the most common pathogens in pleural space infections are Streptococcus anginosus, Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant S. aureus in hospital-acquired cases), anaerobes, and Enterobacterales. Hospital-acquired infections are more likely to involve resistant Gram-negative bacteria [11,12].

- Hemorrhage: Hemorrhage is a recognized but rare complication of pleural effusion paracentesis (thoracentesis) with a risk of significant bleeding (including hemothorax or puncture site bleeding) of approximately ≤1%, as indicated in large meta-analyses and cohort studies. The primary mechanism is misplaced needle or catheter insertion, resulting in laceration of the intercostal artery or its branches, which can lead to chest wall hematoma or hemothorax. Injury to other vascular structures or inadvertent puncture of abdominal organs (e.g., the liver and spleen) is rare but possible, especially for low-lying effusions or with improper techniques. Lack of ultrasound guidance, poor knowledge of the local anatomy, and multiple needle passes increase the risk. Vascular ultrasonography with color Doppler can help avoid vessel injury [26,28].

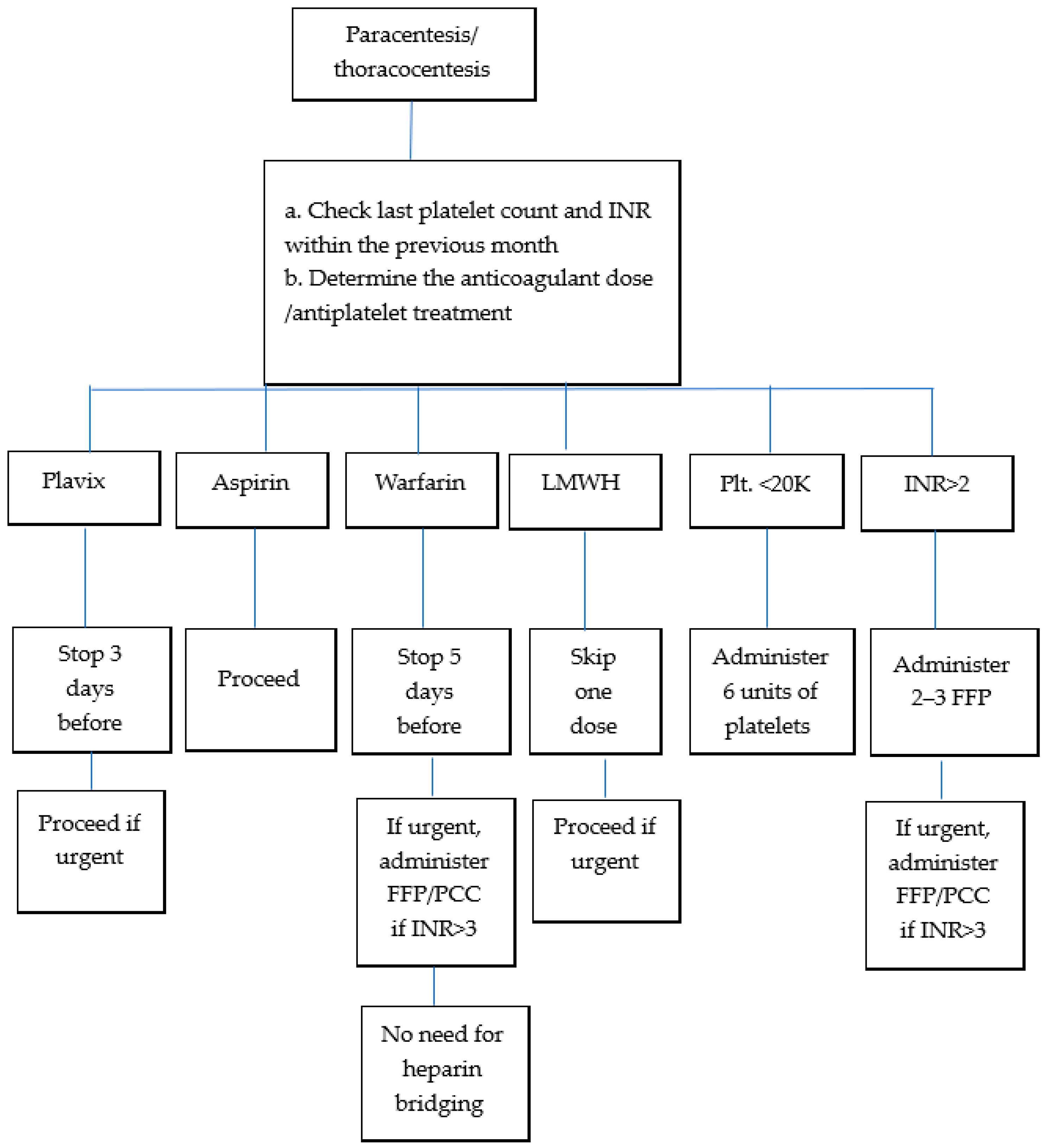

5. Thoracocentesis and Paracentesis in the Coagulopathic Patient

5.1. Severe Thrombocytopenia: Does It Need to Be Corrected, and at What Platelet Threshold?

5.2. Prolonged INR: How Should It Be Managed, and When (If Ever) Should FFP Be Administered?

5.3. Patients on Anticoagulants (Warfarin, DOACs) and Antiplatelet Agents (Aspirin, Clopidogrel, Ticagrelor): Should Therapy Be Stopped Pre-Procedure?

- Urgent procedures: (e.g., large symptomatic effusion, diagnostic paracentesis for suspected spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), most experts proceed without reversing therapeutic warfarin (INR in target range ~2–3.5).

- Elective procedures: INR ~2 should be the limit for pre-procedural correction. Routine “bridging” with heparin is not indicated for these short interruptions during low-risk procedures.

- Aspirin monotherapy: generally continue; no need to stop before thoracentesis or paracentesis.

- Clopidogrel/ticagrelor:

- Elective procedures in low cardiac-risk patients: some practitioners prefer to defer or briefly hold P2Y12 inhibitors for 72 h; this remains a conservative institutional habit rather than an evidence-based requirement.

5.4. Which Patients Are Actually “High Bleeding Risk” for These Procedures?

- Global consumptive or systemic coagulopathy

- DIC

- Severe hyperfibrinolysis

- Hypofibrinogenemia (<100–120 mg/dL)

- Profound thrombocytopenia (<20,000/µL) with evidence of clinical bleeding.

- More invasive pleural or abdominal access than a standard tap.Data supporting safety apply to ultrasound-guided thoracentesis and paracentesis using a small-bore catheter. When larger-bore chest tubes, tunneled drains, thoracoscopy, or closed pleural biopsy are planned, several consensus statements consider these “moderate” or “high bleeding-risk” procedures and recommend more conservative coagulation targets such as platelets > 50,000/µL or correction of major coagulopathy [13,15,16,17,18,30].

- Non–ultrasound-guided (“blind”) access, distorted anatomy, or operator inexperience.

- Ongoing thrombolytic therapy or very recent systemic fibrinolysis.

5.5. Where Do Guidelines and Expert Statements Disagree?

- (a)

- Platelet threshold

- SIR 2019 consensus (interventional radiology):

- Hepatology guidelines (AASLD; British Society of Gastroenterology/BASL):

- Critical care/CHEST transfusion guidance:Endorses a restrictive transfusion strategy and does not impose a universal numeric platelet cutoff above which taps are “safe,” instead focusing on clinical bleeding phenotype and procedure risk category [14]. In practice, hepatology and internal medicine ward culture often remains more cautious below 50 K, while interventional radiology and ICU practice are comfortable down to ~20 K in stable patients.

- (b)

- INR correction with FFP

- AASLD and hepatology guidance:

- SIR consensus:

- Legacy perioperative/surgical policies:

- (c)

- Management of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy

- Interventional radiology/pleural expert statements:

- Traditional perioperative anticoagulation algorithms:Still commonly instruct clinicians to stop clopidogrel/ticagrelor for 5–7 days before almost any invasive procedure and to hold DOACs pre-procedure. These algorithms are largely extrapolated from surgery, neuraxial anesthesia, or moderate/high-risk procedures, not from ultrasound-guided fluid aspiration [8,9,10]. Thus, cardiology (concerned about stent thrombosis), hepatology (concerned about delaying life-saving paracentesis for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), and interventional radiology (comfortable with low needle-track bleeding risk) tend to accept continued antithrombotic therapy, while surgical/anesthesia checklists are sometimes more conservative.

- (d)

- Viscoelastic testing: thromboelastography/rotational thromboelastometry (TEG/ROTEM)

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AASLD | American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases |

| AP | anteroposterior |

| BASL | British Association for the Study of the Liver |

| BNP | B-type natriuretic peptide |

| BP | blood pressure |

| CHEST | American College of Chest Physicians |

| CHF | congestive heart failure |

| CT | computed tomography |

| DIC | disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| DOAC | direct oral anticoagulant |

| DOACs | direct oral anticoagulants |

| FFP | fresh frozen plasma |

| HR | heart rate |

| HRS | hepatorenal syndrome |

| ICU | intensive care unit |

| INR | international normalized ratio |

| LAT | lateral |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| LMWH | low-molecular-weight heparin |

| LVP | large-volume paracentesis |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| PCC | prothrombin complex concentrate |

| PICD | postparacentesis circulatory dysfunction |

| POCUS | point-of-care ultrasound |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCTs | randomized controlled trials |

| ROTEM | rotational thromboelastometry |

| SAAG | serum–ascites albumin gradient |

| SBP | spontaneous bacterial peritonitis |

| SIR | Society of Interventional Radiology |

| TEG | thromboelastography |

| TP | total protein |

| US | ultrasound |

| VAS | visual analog scale |

References

- Gonot-Schoupinsky, F.N.; Garip, G.; Sheffield, D. Facilitating the Planning and Evaluation of Narrative Intervention Reviews: Systematic Transparency Assessment in Intervention Reviews (STAIR). Eval. Program Plan. 2022, 91, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.P.; Aithal, G.P. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut 2021, 70, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggins, S.W.; Angeli, P.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Ginès, P.; Ling, S.C.; Nadim, M.K.; Wong, F.; Kim, W.R. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome: 2021 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2021, 74, 1014–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.S.; Runyon, B.A. Treatment of patients with cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pose, E.; Piano, S.; Juanola, A.; Ginès, P. Hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 588–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyon, B.A. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: Update 2012. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1651–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, J.; Bufalini, J.; Dreer, J.; Shah, V.; King, L.; Wang, L.; Evans, M. Safety of abdominal paracentesis in hospitalized patients receiving uninterrupted therapeutic or prophylactic anticoagulants. anticoagulated patients. Intern. Med. J. 2025, 55, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbert, R.M.; Atwell, T.D.; Lekah, A.; Patel, M.D.; Carter, R.E.; McDonald, J.S.; Rabatin, J.T. Safety of ultrasound-guided thoracentesis in patients with abnormal preprocedural coagulation parameters. Chest 2013, 144, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Dong, J.; Weng, Z.; Shao, L.; Chen, J.; Jiang, J. Hemorrhagic complications following abdominal paracentesis. Medicine 2015, 94, e2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dorin, S.; Schwartz, A.; Tudas, R.; Sanchez, K.; Amarneh, M.; Kuperman, E. Bleeding risks with apixaban during paracentesis. Cureus 2025, 17, e80299. [Google Scholar]

- Paparoupa, M.; Wege, H.; Creutzfeldt, A.; Sebode, M.; Uzunoglu, F.G.; Boenisch, O.; Nierhaus, A.; Izbicki, J.R.; Kluge, S. Perforation of the ascending colon during implantation of an indwelling peritoneal catheter: A case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.L.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.; Thorpe, K.E.; Straus, S.E. Does this patient have bacterial peritonitis or portal hypertension? How do I perform a paracentesis and analyze the results? JAMA 2008, 299, 1166–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, I.J.; Rahim, S.; Davidson, J.C.; Hanks, S.E.; Tam, A.L.; Walker, T.G.; Wilkins, L.R.; Sarode, R.; Weinberg, I. Society of Interventional Radiology Consensus Guidelines for the Periprocedural Management of Thrombotic and Bleeding Risk in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Image-Guided Interventions. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2019, 30, 1168–1184.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruder-Rassi, A.; d’Amico, E.A.; Tripodi, A.; Flores da Rocha TRMigata, B.U.; Ferreira, C.M.; Carrilho, F.J.; Farias, A.Q. Fresh Frozen Plasma transfusion in patients with cirrhosis and coagulopathy: Effect on conventional coagulation tests and thrombomodulin-modified thrombin generation. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biolato, M.; Vitale, F.; Galasso, T.; Gasbarrini, A.; Grieco, A. Minimum platelet count threshold before invasive procedures in cirrhosis: Evolution of the guidelines. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 15, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.; Jensen, T.; Reierson KMathew, B.; Bahagra, A.; Franco-sadud, R.; Grikis, L.; Mader, M.; Dancel, R.; Lucas, B.P.; Soni, N. Recommendations on the use of ultrasound for adult abdominal paracentesis: A position statement of the society of hospital medicine. J. Hosp. Med. 2019, 14, E7–E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.L.; Lokan, T.; Chinnaratha, M.A.; Veysey, M. Risk of bleeding after abdominal paracentesis in liver disease: A meta-analysis. JGH Open 2024, 8, e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intagliata, N.M.; Davitkov, P.; Allen, A.M.; Falck-Ytter, Y.T.; Stine, J.G. AGA technical review on coagulation in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1630–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, G.; Castellote, J.; Alvarez, C.; Girbau, A.; Gordillo, J.; Baliellas, C.; Casas, M.; Pons, C.; Román, E.M.; Maisterra, S.; et al. Secondary bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: A retrospective study of clinical and analytical characteristics, diagnosis and management. J. Hepatol. 2010, 52, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.T.; Matthay, M.A.; Harris, H.W. Secondary peritonitis: Principles of diagnosis and intervention. BMJ 2018, 361, k1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M.; Binnicker, M.J.; Campbell, S.; Carroll, K.C.; Chapin, K.C.; Gilligan, P.H.; Gonzalez, M.D.; Jerris, R.C.; Kehl, S.C.; Patel, R.; et al. Guide to utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2024 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinchot, J.W.; Kalva, S.P.; Majdalany, B.S.; Kim, C.Y.; Ahmed, O.; Asrani, S.K.; Cash, B.D.; Eldrup-Jorgensen, J.; Kendi, A.T.; Scheidt, M.J.; et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® radiologic management of portal hypertension. JACR 2021, 18, S153–S173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asciak, R.; Bedawi, E.O.; Bhatnagar, R.; Clive, A.O.; Hassan, M.; Lloyd, H.; Reddy, R.; Roberts, H.; Rahman, N.M. British Thoracic Society clinical statement on pleural procedures. Thorax 2023, 78, s43–s68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, M.E.; Chong, C.A.; Stanbrook, M.B.; Tricco, A.C.; Wong, C.; Straus, S.E. Does this patient have an exudative pleural effusion? The Rational Clinical Examination systematic review. JAMA 2014, 311, 2422–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yataco, A.C.; Soghier, I.; Hébert, P.C.; Belley-Cote, E.; Disselkamp, M.; Flynn, D.; Halvorson, K.; Iaccarino, J.M.; Lim, W.; Lindenmeyer, C.C.; et al. Transfusion of fresh frozen plasma and platelets in critically ill adults: An American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline. Chest 2025, 168, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, K.; Epelbaum, O. Percutaneous pleural drainage in patients taking clopidogrel: Real danger or phantom fear? JAMA 2014, 311, 2422–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaralingam, A.; Bedawi, E.O.; Harriss, E.K.; Munavvar, M.; Rahman, N.M. The frequency, risk factors, and management of complications from pleural procedures. Chest 2022, 161, 1407–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar, A.E.S.; Landaeta, M.F.; Adrianza, A.M.; Aldana, G.L.; Pozo, L.; Armas-Villalba, A.; Toquica, C.C.; Larson, A.J.; Vial, M.R.; Grosu, H.B.; et al. Complications following symptom-limited thoracentesis using suction. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 1902356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangers, L.; Giovannelli, J.; Mangiapan, G.; Alves, M.; Bigé, N.; Messika, J.; Morawiec, E.; Neuville, M.; Cracco, C.; Béduneau, G.; et al. Antiplatelet drugs and risk of bleeding after bedside pleural procedures: A national multicenter cohort study. Chest 2021, 159, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, J.T.; Argento, A.C.; Murphy, T.E.; Araujo, K.L.; Pisani, M.A. The safety of thoracentesis in patients with uncorrected bleeding risk. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2013, 10, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz Demirci, N.; Koksal, D.; Bilaceroglu, S.; Ogan, N.; Atinkaya, C.; Ozhan, M.; Ak, G. Management of bleeding risk before pleural procedures. Eurasian J. Pulmonol. 2020, 22, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBiasi, E.M.; Murphy, T.E.; Araujo, K.L.B.; Pisani, M.A.; Puchalski, J.T. Physician practice patterns for performing thoracentesis in patients taking anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, 17, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano, G.; La Via, L.; Terminella, A.; Sorbello, M. Re-expansion pulmonary edema as a life-threatening complication in massive, long-standing pneumothorax: A case series and literature review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.; Chang- Tan, C.W.; Yan Tan, D.K. Safety of thoracocentesis and tube thoracostomy in patient with uncorrected coagulopathy: Asystematic review and Meta-analysis. Chest 2021, 160, 1875–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aithal, G.P.; Palaniyappan, N.; China, L.; Härmälä, S.; Macken, L.; Ryan, J.M.; Wilkes, E.A.; Moore, K.; Leithead, J.A.; Hayes, P.C.; et al. Guidelines on the Management of Ascites in Cirrhosis. British Society of Gastroenterology and British Association for the Study of the Liver. Gut 2020, 69, 9–29. [Google Scholar]

| Section | Suggestion |

|---|---|

| Preprocedural suggestions | |

| 1. Informed consent | Obtain verbal consent and document. Written consent should be obtained only if required by institutional policy. |

| 2. First-time paracentesis | Provide a full explanation of the risks in the patient’s native language. Document the explanation, clinician’s name, and language used. |

| 3. Exclude acute infection | Postpone the procedure if active infection is suspected. |

| 4. Coagulation guidance | No repeat tests if no coagulopathy history and normal test results in the past month. a. DOACs: Stop 24 h prior (skip one dose). Proceed if emergency drainage required. b. Warfarin: Stop 5 d prior; confirm INR < 2.0. If emergency, correct with FFP/PCC above INR-3.0. c. Clexane (LMWH): Hold 12 h (skip last dose). Proceed if emergency drainage required. d. Aspirin: proceed. e. Plavix: Stop 72 h prior. Proceed if emergency drainage required. f. Platelet count < 20,000/μL: Administer 6 units. g. INR > 2.0: Administer ≤ 3 FFP units. (~0.3 INR correction per unit) [1]. If emergency correct with FFP/PCC above INR-3.0. h. TEG: Optional if available. |

| 5. Baseline vitals | Record temperature, pulse, BP, and oxygen saturation. |

| Technique suggestions | |

| 1. Ultrasound guidance | Mandatory for all procedures. |

| 2. Needle placement | Avoid the midline. Insert 8 cm lateral to the midline and 5 cm above the pubic symphysis or 2 cm below the umbilicus. |

| 3. Drainage system | Use either an 8F Seldinger kit or 18G cannula. |

| 4. Volume | No restriction on the amount of peritoneal fluid drained (unlike pleural effusion). |

| 5. Diagnostic fluid sampling | Always analyze fluid for cell count. If neutrophil count is >250/mm3 → suspect SBP. If a catheter is in place → perform culture testing. |

| 6. Device options | Either an 8F Seldinger set or 18G peripheral catheter is acceptable. |

| 7. Initial/diagnostic studies | Analyze fluid for: cell count, culture, albumin, TP, amylase, BNP (optional), cytology. |

| 8. Albumin administration | Administer 8–10 g albumin for each 1 L of drainage (only >5 L) (to prevent paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction) |

| Post-paracentesis care | |

| 1. Observation | Monitor patients for 1 h after catheter removal |

| 2. Bed rest | Keep patient in bed for the first 30 min post removal. |

| 3. Discharge criteria | Discharge only after documentation of stable BP and HR. Ensure parameters are recorded. |

| 4. Leakage from site. | If leakage occurs, place a pressure bandage. If leakage does not stop, a single suture may be placed. Remove suture after 1 week. |

| 5. Resuming anticoagulation/anti-platelets | Resume anticoagulants (including clopidogrel) the day after the procedure. |

| Bleeding management | |

| 1. Bloody aspirate | Serosanguinous initial fluid is acceptable. If bloody fluid follows clear drainage → stop immediately. If the initial aspirate is blood → abort and remove the catheter. |

| 2. Bleeding response | a. Monitor for 4 h with vitals assessed every hour. b. Repeat hemoglobin testing after 1 h. Perform blood type testing. |

| Admission criteria post-paracentesis | |

| 1. SBP | Confirmed SBP diagnosis. |

| 2. Hemodynamic instability | Hemodynamic changes or a drop in hemoglobin level > 1 g/dL. |

| 3. Severe pain or hematoma | VAS ≥ 7 + expanding hematoma → consider urgent abdominal CT angiography. |

| Documentation checklist | |

| 1. Indication | Document the indication for the procedure |

| 2. Consent | Obtain and document verbal or written consent. |

| 3. Physical/POCUS findings | Record the physical exam and POCUS findings. |

| 4. Technique | Document the insertion technique and exact place. |

| 5. Vital signs | Record pre- and post-procedure vital signs. |

| 6. Anticoagulation | Document anticoagulation status and last dose timing. |

| 7. Laboratory test results | Include relevant laboratory test results and hemostasis assessment |

| Section | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Preprocedural requirements and suggestions | |

| 1. Imaging | Localize effusion using POCUS. |

| 2. Access point | Two intercostal spaces below the fluid peak in the posterior mid-clavicular line with the patient seated, arms forward. Above the rib. |

| 3. Needle/drainage Kit | 20–21G cannula or 6–8F Seldinger catheter. |

| 4. Coagulation guidance | No repeat tests if no coagulopathy history and normal test results in the past month. a. DOACs: Stop 24 h prior. (skip one dose). Proceed if emergency drainage required. b. Warfarin: Stop 5 d prior; confirm INR < 2.0. If emergency drainage required, correct with FFP/PCC only if INR > 3.0. c. Clexane (LMWH): Hold 24 h (2 doses). Proceed if emergency drainage required. d. Aspirin: Continue [13]. e. Plavix: Stop 72 h prior [13,27]. Proceed if emergency drainage required. f. Platelet count < 20,000/μL: Administer 6 units. g. In elective procedure if INR > 2.0 administer ≤ 3 FFP units. If emergency drainage required, correct with FFP/PCC only if INR > 3.0. h. TEG: Optional if available. |

| Procedure guidance | |

| 1. Bilateral drainage | Do not perform on the same day. |

| 2. Volume limit | Do not exceed 1.5 L drainage per session [25]. |

| 3. Drainage method | Use gravity drainage. Avoid vacuum suction [2]. |

| 4. Anesthesia | Use 1% lidocaine for local anesthesia [25]. |

| 5. Diagnostic testing | Send pleural fluid for pH, LDH, glucose, protein, cytology, and BNP assessments. |

| Post-procedure care | |

| 1. Vital signs | Monitor hourly for 2 h. |

| 2. Imaging | Chest radiography (AP + LAT) 1 h post-procedure [25]. |

| 3. Anticoagulation/anti-platelets | Restart the next day. |

| Admission criteria post procedure | |

| New dyspnea/hypoxemia | Pneumothorax in X-ray. blood aspiration or aspirated fluid became bloody during drainage-suspected hemothorax. |

| Hemodynamic instability | Suspect Tension pneumothorax (emergency thoracocentesis) |

| Documentation checklist | |

| 1. Indication | Document the indication for the procedure. |

| 2. Consent | Obtain and document verbal or written consent. |

| 3. Physical/POCUS Findings | Record the physical exam and POCUS findings. |

| 4. Technique | Document the insertion technique. |

| 5. Vital Signs | Record pre- and post-procedure vital signs. |

| 6. Anticoagulation | Document anticoagulation status and last dose timing. |

| 7. Laboratory test results | Include relevant laboratory test results and hemostasis assessment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bartal, C.; Sikuler, E.; Tsenter, P.; Perski, V.; Dvorkin, V.; Pairous, R.; Schwartz, D. Proposed Clinical Practice Guidance for Large-Volume Abdominal and Pleural Paracentesis with Emphasis on Coagulopathy Management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8287. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238287

Bartal C, Sikuler E, Tsenter P, Perski V, Dvorkin V, Pairous R, Schwartz D. Proposed Clinical Practice Guidance for Large-Volume Abdominal and Pleural Paracentesis with Emphasis on Coagulopathy Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8287. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238287

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartal, Carmi, Emanuel Sikuler, Philip Tsenter, Vitali Perski, Valery Dvorkin, Roman Pairous, and Doron Schwartz. 2025. "Proposed Clinical Practice Guidance for Large-Volume Abdominal and Pleural Paracentesis with Emphasis on Coagulopathy Management" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8287. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238287

APA StyleBartal, C., Sikuler, E., Tsenter, P., Perski, V., Dvorkin, V., Pairous, R., & Schwartz, D. (2025). Proposed Clinical Practice Guidance for Large-Volume Abdominal and Pleural Paracentesis with Emphasis on Coagulopathy Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8287. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238287