Advantages and Disadvantages of Commonly Used Urinary Incontinence Questionnaires—How to Correctly Choose Questionnaire in Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis?

Abstract

1. Introduction

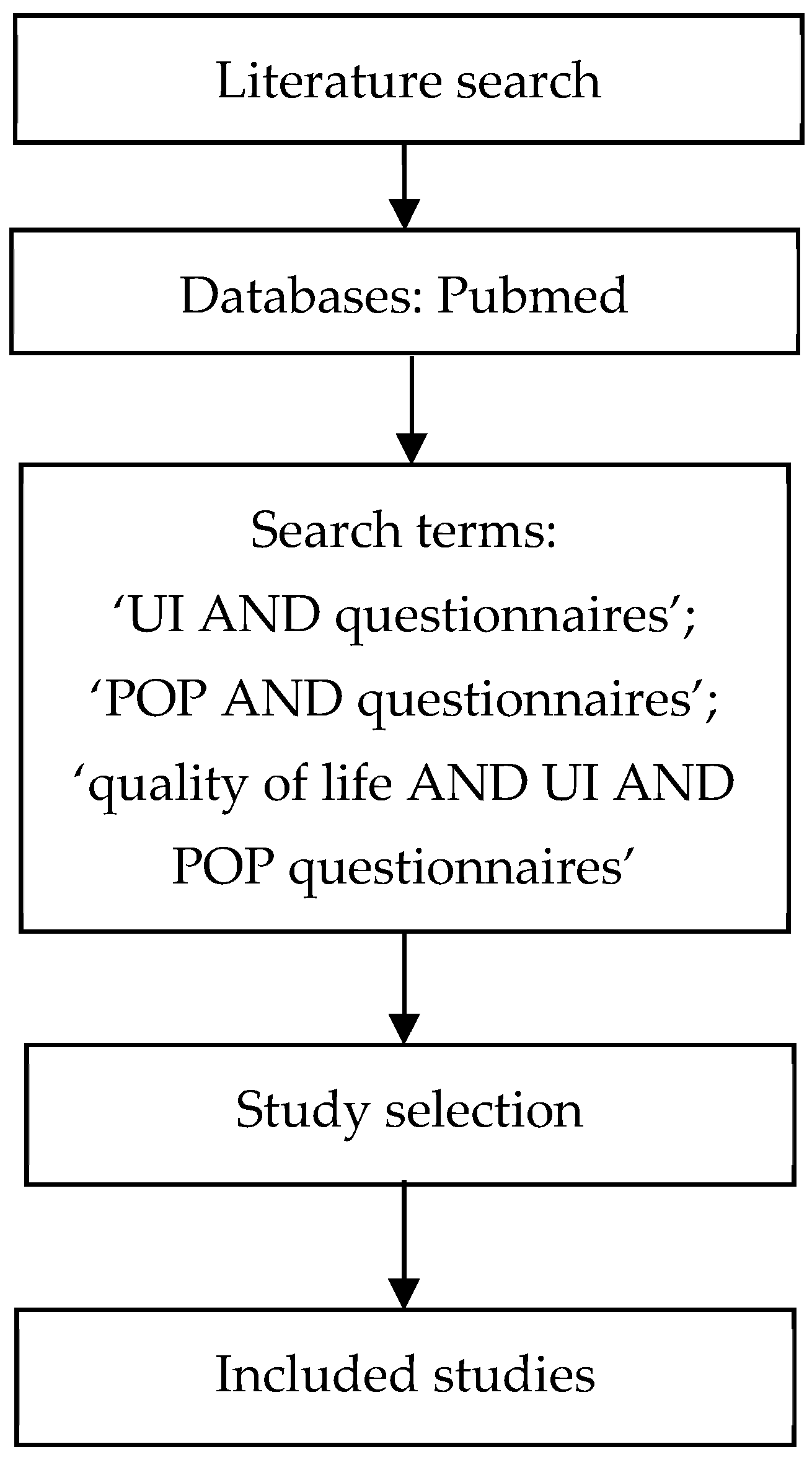

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ)—Grade: A

2.2. International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire—Urinary Incontinence Module (ICIQ-UI Short Form)—Grade: A

2.3. International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire—Overactive Bladder Module (ICIQ-OAB)—Grade: A

2.4. King’s Health Questionnaire (KHQ)—Grade: A

2.5. The Urogenital Distress Inventory Short Form (UDI-6)—Grade: A

- Frequent urination;

- Leakage triggered by urgency;

- Leakage linked to physical exertion;

- Leakage occurring during coughing or sneezing (small volumes);

- Difficulty with bladder emptying;

- Discomfort or pain in the lower abdomen or genital region.

- Irritative Symptoms (IS): items 1 and 2;

- Stress Symptoms (SS): items 3 and 4;

- Obstructive/Discomfort Symptoms (OS): items 5 and 6 [23].

2.6. The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Short Form (IIQ-7)—Grade: A

- Household chores;

- Physical recreation;

- Entertainment activities;

- Travel beyond 30 min from home;

- Social interactions;

- Emotional well-being;

- Feelings of frustration.

- Physical Activity (PA): items 1 and 2;

- Travel (TR): items 3 and 4;

- Social Activities (SA): item 5;

- Emotional Health (EH): items 6 and 7 [23].

- Scores below 50 are associated with good QoL;

- Scores between 50 and 70 indicate moderate QoL;

- Scores above 70 reflect poor QoL [32].

2.7. Overactive Bladder Questionnaire (OAB-q)—Grade: A

2.8. ICIQ Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (I-QOL): Instrument Description and Clinical Application)—Grade: A

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

- Routine Clinical Practice

- For initial screening and severity assessment, the ICIQ-UI Short Form or UDI-6 are recommended.

- →

- Both are brief, easy to administer, and offer rapid insight into symptom burden and impact on daily functioning.

- The KHQ and I-QOL are valuable for comprehensive quality-of-life assessment in routine follow-up and post-treatment evaluation.

- Combining a symptom questionnaire (e.g., ICIQ-UI SF) with a QoL measure (e.g., KHQ or I-QOL) provides the most holistic assessment.

- Research and Clinical Trials

- Studies evaluating treatment outcomes or longitudinal changes should prioritize instruments with established responsiveness and defined MCID values, such as the KHQ, I-QOL, and OAB-q.

- For differentiating between urinary incontinence subtypes (SUI, UUI, MUI, OAB), combined use of ICIQ-UI SF and ICIQ-OAB is advisable, as they complement each other in symptom profiling.

- Target Population Considerations

- The ICIQ Modular System provides flexibility for diverse patient groups, including men, women, pediatric populations, and cognitively impaired individuals.

- For older adults or patients with multiple comorbidities, shorter tools such as UDI-6 and IIQ-7 minimize respondent fatigue while maintaining clinical relevance.

- Diagnostic vs. Follow-Up Use

- Screening and Diagnostic Purposes: ICIQ-UI SF, UDI-6, ICIQ-OAB.

- Monitoring and Outcome Evaluation: KHQ, I-QOL, OAB-q, IIQ-7.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UI | urinary incontinence |

| SUI | stress urinary incontinence |

| OAB | overactive bladder |

| MUI | mixed urinary incontinence |

| ICS | International Continence Society |

| IUGA | International Urogynecological Association |

| PROMs | Patient-reported outcome measures |

| QoL | quality of life |

| ICIQ | The International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire |

| ICIQ-UI SH | International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire—Urinary Incontinence Module (short form) |

| ICIQ-OAB | International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire—Overactive Bladder Module |

| KHQ | King’s Health Questionnaire |

| HRQoL | health-related quality of life |

| GH | general health |

| RE | role limitations—emotional |

| RP | role limitations-physical |

| SL | social limitations |

| PR | personal relationships |

| E | emotions |

| S/E | sleep/energy |

| SM | symptom severity |

| MID | minimally important difference |

| USI | urodynamic stress incontinence |

| UDI- 6 | The Urogenital Distress Inventory–Short Form |

| IS | Irritative Symptoms |

| SS | Stress Symptoms |

| OS | Obstructive/Discomfort Symptoms |

| DI | detrusor instability |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| IIQ-7 | The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Short Form |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| TR | Travel |

| SA | Social Activities |

| EH | Emotional Health |

| NN | neural network |

| OAB-q | Overactive Bladder Questionnaire |

| LUTS | lower urinary tract symptoms |

| ICI | the International Consultation on Incontinence |

References

- D’Ancona, C.; Haylen, B.; Oelke, M.; Abranches-Monteiro, L.; Arnold, E.; Goldman, H.; Hamid, R.; Homma, Y.; Marcelissen, T.; Rademakers, K.; et al. An International Continence Society (ICS) Report on the Terminology for Adult Male Lower Urinary Tract and Pelvic Floor Symptoms and Dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2019, 38, 433–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunskaar, S.; Vinsnes, A. The quality of life in women with urinary incontinence as measured by the Sickness Impact Pro¢le. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1991, 39, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, T.; Mitranovici, M.I.; Moraru, L.; Costachescu, D.; Caravia, L.G.; Bernad, E.; Ivan, V.; Apostol, A.; Munteanu, M.; Puscasiu, L. Innovations in Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Narrative Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: www.iciq.net (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Avery, K.; Donovan, J.; Peters, T.; Shaw, C.; Gotoh, M.; Abrams, P. ICIQ: A brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2004, 23, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.; Badia, X.; Corcos, J.; Jackson, S.; Naughton, M.; Radley, S.; Valiquette, L.; Batista, J.E.; Avery, K.; Donovan, J.; et al. Symptom and quality of life assessment. In Incontinence: Proceedings of the Second International Consultation on Incontinence, 2nd ed.; Cardozo, L., Khoury, S., Wein, A., Eds.; Health Publication Ltd.: Plymouth, UK, 2001; pp. 267–316. [Google Scholar]

- Espuña Pons, M.; Rebollo Alvarez, P.; Puig Clota, M. Validation of the Spanish version of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form. A questionnaire for assessing the urinary incontinence. Med. Clin. 2004, 122, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieres, P.; Rokita, W.; Stanisławska, M.; Rechberger, T.; Gałezia, M. The diagnostic value of chosen questionnaires (UDI 6SF, Gaudenz, MESA, ICIQ-SF and King’s Health Questionnaire) in diagnosis of different types of women’s urinary incontinence. Ginekol. Pol. 2008, 79, 338–341. [Google Scholar]

- Nyström, E.; Asklund, I.; Lindam, A.; Samuelsson, E. Minimum important difference of the ICIQ-UI SF score after self-management of urinary incontinence. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, P.; Avery, K.; Gardener, N.; Donovan, J. The International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire: www.iciq.net. J. Urol. 2006, 175, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotar, M.; Trsinar, B.; Kisner, K.; Barbic, M.; Sedlar, A.; Gruden, J.; Vodusek, D.B. Correlations between the ICIQ-UI short form and urodynamic diagnosis. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2009, 28, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verghese, T.S.; Middleton, L.J.; Daniels, J.P.; Deeks, J.J.; Latthe, P.M. The impact of urodynamics on treatment and outcomes in women with an overactive bladder: A longitudinal prospective follow-up study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, C.J.; Cardozo, L.D.; Khullar, V.; Salvatore, S. A new questionnaire to assess the quality of life of urinary incontinent women. Br. J. ObstetGynaecol. 1997, 104, 1374–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelleher, C.J.; Pleil, A.M.; Reese, P.R.; Burgess, S.M.; Brodish, P.H. How much is enough and who says so? BJOG 2004, 111, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reese, P.R.; Pleil, A.M.; Okano, G.J.; Kelleher, C.J. Multinational study of reliability and validity of the King’s Health Questionnaire in patients with overactive bladder. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwon, B.E.; Kim, G.Y.; Son, Y.J.; Roh, Y.S.; You, M.A. Quality of life of women with urinary incontinence: A systematic literature review. Int. Neurourol. J. 2010, 14, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, R.; Pereira, I.; Henriques, A.; Ribeirinho, A.L.; Valentim-Lourenço, A. King’s Health Questionnaire to assess subjective outcomes after surgical treatment for urinary incontinence: Can it be useful? Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanini, J.; Dambros, M.; D’Ancona, C.; Palma, P. Concurrent validity, internal consistency and responsiveness of the Portuguese version of the King’s Health Questionnaire (KHQ) in women after stress urinary incontinence surgery. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2004, 30, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriadis, T.; Giannoulis, G.; Zacharakis, D.; Protopapas, A.; Cardozo, L.; Athanasiou, S. The “1-3-5 cough test”: Comparing the severity of urodynamic stress incontinence with severity measures of subjective perception of stress urinary incontinence. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 27, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digesu, G.A.; Salvatore, S.; Fernando, R.; Khullar, V. Mixed urinary symptoms: What are the urodynamic findings? Neurourol. Urodyn. 2008, 27, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikus, M.; Ćorić, M.; Matak, L.; Škegro, B.; Vujić, G.; Banović, V. Validation of the UDI-6 and the ICIQ-UI SF-Croation version. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 2625–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumaker, S.A.; Wyman, J.F.; Uebersax, J.S.; McClish, D.; Fantl, J.A. Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Qual. Life Res. 1994, 3, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebersax, J.S.; Wyman, J.F.; Shumaker, S.A.; McClish, D.K.; Fantl, J.A.; the Continence Program for Women Research Group. Short Forms to Assess Life Quality Symptom Distress for Urinary Incontinence in Women: The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Neurourol. Urodyn. 1995, 14, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlTaweel, W.M.; Seyam, R.; Alsulihem, A.A. Relationship between urinary incontinence symptoms and urodynamic findings using a validated Arabic questionnaire. Ann. Saudi Med. 2016, 36, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorupska, K.A.; Miotla, P.; Kubik-Komar, A.; Skorupski, P.; Rechberger, T. Development and validation of the Polish version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory short form and the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire short form. Eur. J. ObstetGynecolReprod Biol. 2017, 215, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemack, G.E.; Zimmern, P.E. Predictability of urodynamic findings based on the Urogenital Distress Inventory questionnaire. Urology 1999, 54, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharipova, K.; Pilsetniece, Z.; Bekmukhambetov, Y.; Vjaters, E. The Correlation of Urethral Pressure Profilometry Data in Women with Different Types of Urinary Incontinence. Urol. Int. 2016, 97, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokmeci, F.; Seval, M.; Gok, H. Comparison of ambulatory versus conventional urodynamics in females with urinary incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2010, 29, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, L.; Stoddard, A.; Richter, H.; Zimmern, P.; Moalli, P.; Kraus, S.R.; Norton, P.; Lukacz, E.; Sirls, L.; Johnson, H. Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Mixed incontinence: Comparing definitions in women having stress incontinence surgery. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2009, 28, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticone, M.; Ferriero, G.; Giordano, A.; Foti, C.; Franchignoni, F. Rasch analysis of the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire short version (IIQ-7) in women with urinary incontinence. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2020, 43, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.M.; Xiao, H.; Ji, Z.G.; Yan, W.G.; Zhang, Y.S. TVT versus TOT in the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2018, 14, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcos, J.; Behlouli, H.; Beaulieu, S. Identifying cut-off scores with neural networks for interpretation of the incontinence impact questionnaire. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2002, 21, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribillaga, L.; Ledesma, M.; Montedoro, A.; Pisano, F.; Bengió, R.G.; Oulton, G.; Grutadauria, G.; Bengió, R.H. Is there a correlation between abdominal leak pressure point, incontinence severity and quality of life in patients with stress urinary incontinence? Arch. Esp. Urol. 2018, 71, 752–756. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, K.; Revicki, D.; Hunt, T.; Corey, R.; Stewart, W.; Bentkover, J.; Kurth, H.; Abrams, P. Psychometric validation of an overactive bladder syndrome and health- related quality of life questionnaire: The OAB-q. Qual Life Res. 2002, 11, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.S.; Matza, L.S.; Thompson, C. The responsiveness of the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire (OAB-q). Qual Life Res. 2005, 14, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matza, L.S.; Zyczynski, T.M.; Bavendam, T. A review of quality of life questionnaires for urinary incontinence and overactive bladder: Which ones to use and why? Curr. Urol. Rep. 2004, 5, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, D.L.; Martin, M.L.; Bushnell, D.M.; Yalcin, I.; Wagner, T.H.; Buesching, D.P. Quality of life of women with urinary incontinence:further development of the incontinence quality of life instrument (I-QOL). Urology 1999, 53, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, T.H.; Patrick, D.L.; Bavendam, T.G.; Martin, M.L.; Buesching, D.P. Quality of life of persons with urinary incontinence: Development of a new mesure. Urology 1996, 47, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bump, R.C.; Norton, P.A.; Zinner, N.R.; Yalcin, I. Mixed urinary incontinence symptoms: Urodynamic findings, incontinence severity, and treatment response. Obtet. Gynecol. 2003, 102, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, J.L.; Miller, E.A.; Fialkow, M.F.; Lentz, G.M.; Miller, J.L.; Fenner, D.E. Relationship between patients report and physician assessment of urinary incontinence severity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 189, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewison, A.; McCaughan, D.; Watt, I. An evaluative review of questionnaires recommended for the assessment of quality of life and symptom severity in women with urinary incontinence. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 2998–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.; Liong, M.L.; Lim, K.K.; Leong, W.S.; Yuen, K.H. The Minimum Clinically Important Difference of the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaires (ICIQ-UI SF and ICIQ-LUTSqol). Urology 2019, 133, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. Techniques of questionnaire design. In Handbook of Health Research Methods: Investigation, Measurement and Analysis; Bowling, A., Ebrahim, E., Eds.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005; pp. 394–427. [Google Scholar]

- Black, N.; Griffiths, J.; Pope, C. Development of a symptom severity index and a symptom impact index for stress incontinence in women. Neurourol. Urodyn. 1996, 15, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.D.; Lin, T.L.; Hu, S.W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lin, L.-Y. Prevalence and correlation of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in Taiwanese women. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2003, 22, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stach-Lempinen, B.; Kujansuu, E.; Laippala, P.; Metsanoja, R. Visual Analogue scale, urinary incontinence severity score, and 15 D-psychometric testing of three different health-related quality-of-life instruments for urinary incontinent women. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 2001, 35, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DuBeau, C.E.; Kiely, D.K.; Resnick, N.M. Quality- of-life impact of urge incontinence in older persons: A new measure and conceptual structure. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1999, 47, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, G.S.; Kiniors, M.; Wientjes, H. Urinary incontinence handicap inventory. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 1994, 19, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.S.; Reid, D.W.; Saltmarche, A.; Linton, L. Measuring the Psychosocial impact of urinary incontinence: The York Incontinence Perceptions Scale (YIPS). J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1995, 43, 1275–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questionnaire | No. of Items | Psychometric Performance | Target Population | Clinical Purpose | Key Domains/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICIQ (Modular System) | 19 modules (varies per module) | Excellent validity, reliability, and responsiveness; widely validated and translated into 43 languages | Men, women, pediatric, cognitively impaired, neurogenic, etc. | Screening, diagnosis, follow-up | Comprehensive modular approach covering urinary, vaginal, bowel, and QoL domains |

| ICIQ-UI Short Form | 4 | High internal consistency and sensitivity to change; correlates with pad test and urodynamics | Men and women with urinary incontinence | Screening, diagnosis, follow-up | Frequency, severity, and QoL impact of UI |

| ICIQ-OAB | 4 | Strong validity and responsiveness; aligns with urodynamic findings | Men and women with overactive bladder | Diagnosis, follow-up | Frequency, nocturia, urgency, UUI |

| King’s Health Questionnaire (KHQ) | 21 | Excellent reliability and validity; clinically meaningful change ≥5–10 points | Women with UI (SUI, OAB, MUI) | Diagnosis, follow-up | HRQoL across multiple domains (physical, social, emotional) |

| UDI-6 | 6 | High reliability and validity; responsive to treatment; good for screening | Women with SUI, OAB, POP | Screening, follow-up | Irritative, stress, and obstructive/discomfort symptoms |

| IIQ-7 | 7 | Strong psychometric properties; unidimensional; good test–retest reliability | Women with SUI, OAB, MUI | Follow-up, treatment outcome | Physical, travel, social, and emotional impact |

| OAB-q (short form) | 33 (8 symptom + 25 HRQoL) | Excellent internal consistency and sensitivity; responsive to therapy | Men and women with OAB | Diagnosis, follow-up | Symptom bother and HRQoL (coping, concern, sleep, social) |

| I-QOL (ICIQ module) | 22 | Excellent reliability and validity; sensitive to severity and treatment response | Men and women (validated mainly in women) | Diagnosis, follow-up | Avoidance, psychosocial impact, embarrassment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skorupska, K.; Kamińska, A. Advantages and Disadvantages of Commonly Used Urinary Incontinence Questionnaires—How to Correctly Choose Questionnaire in Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228196

Skorupska K, Kamińska A. Advantages and Disadvantages of Commonly Used Urinary Incontinence Questionnaires—How to Correctly Choose Questionnaire in Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228196

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkorupska, Katarzyna, and Aleksandra Kamińska. 2025. "Advantages and Disadvantages of Commonly Used Urinary Incontinence Questionnaires—How to Correctly Choose Questionnaire in Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis?" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228196

APA StyleSkorupska, K., & Kamińska, A. (2025). Advantages and Disadvantages of Commonly Used Urinary Incontinence Questionnaires—How to Correctly Choose Questionnaire in Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228196