Distinct Gut Microbiome Signatures in Hemodialysis and Kidney Transplant Populations

Highlights

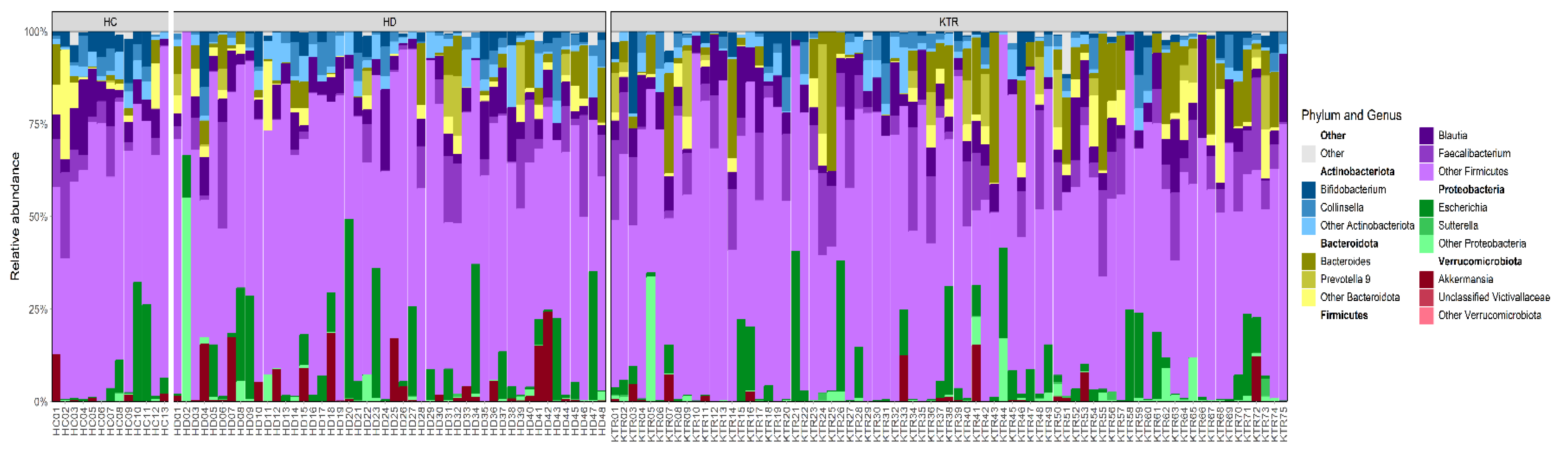

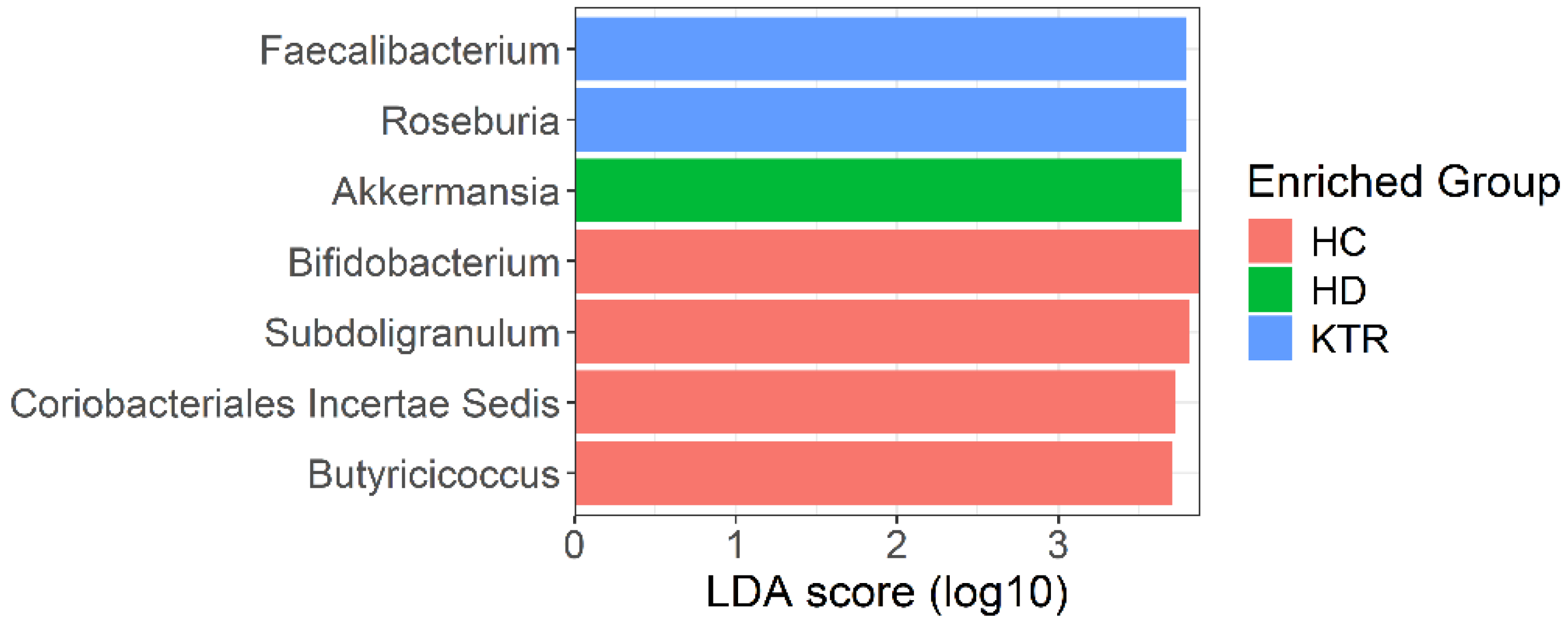

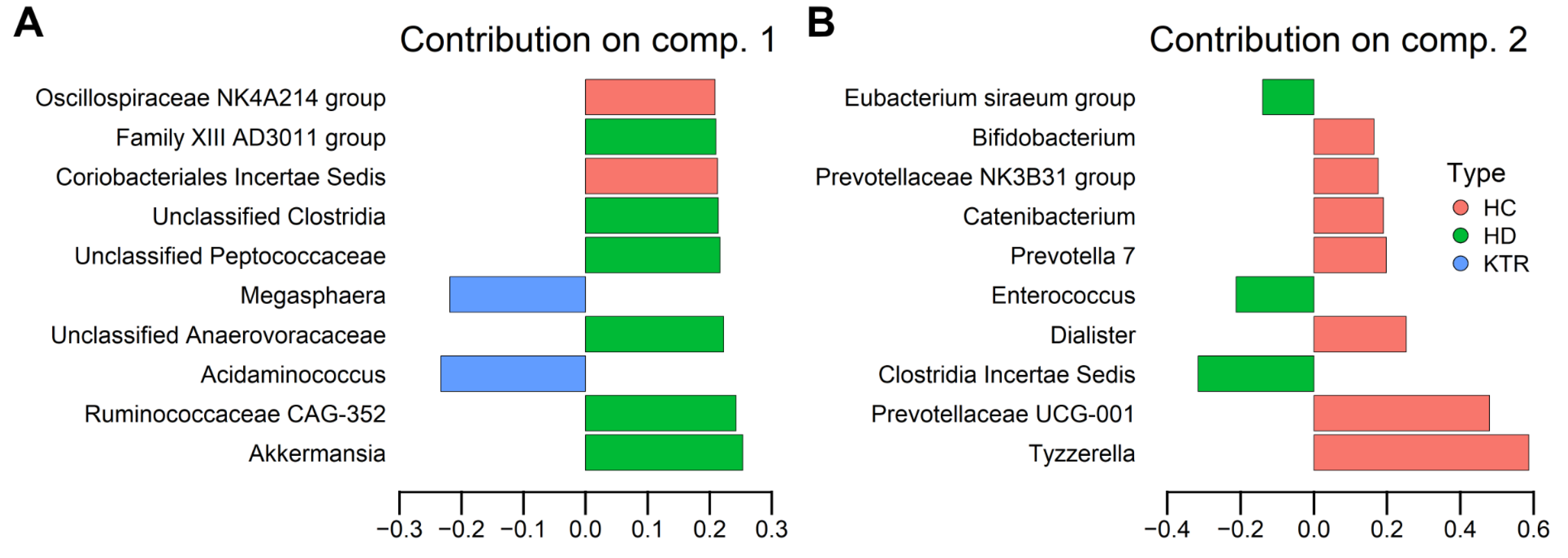

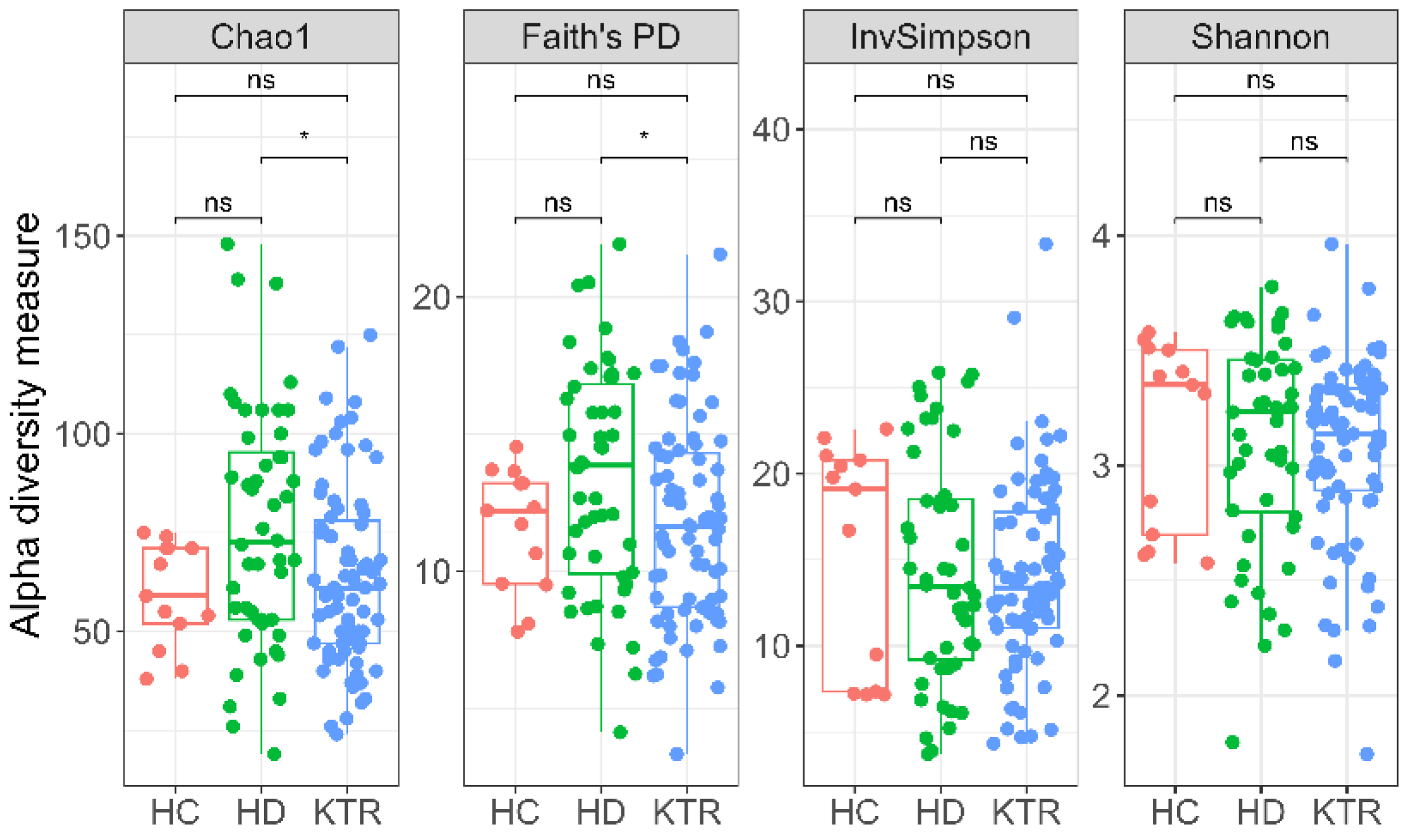

- Gut microbiota composition differs markedly between hemodialysis (HD) patients, kidney transplant recipients (KTR), and healthy controls (HC).

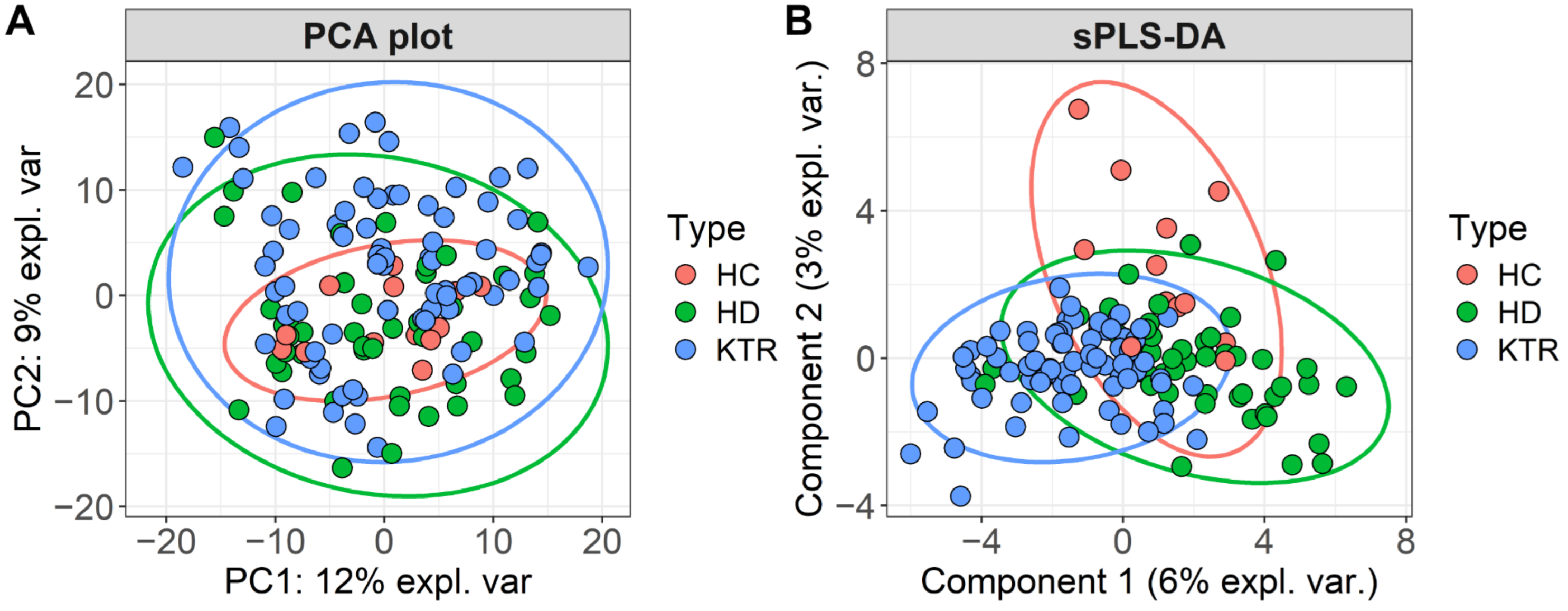

- HD patients showed enrichment of Akkermansia and Clostridia-related taxa, while KTR exhibited partial recovery of SCFA-producing genera such as Faecalibacterium and Roseburia.

- Microbial diversity was higher in HD compared with KTR, but both groups displayed dysbiosis relative to healthy controls.

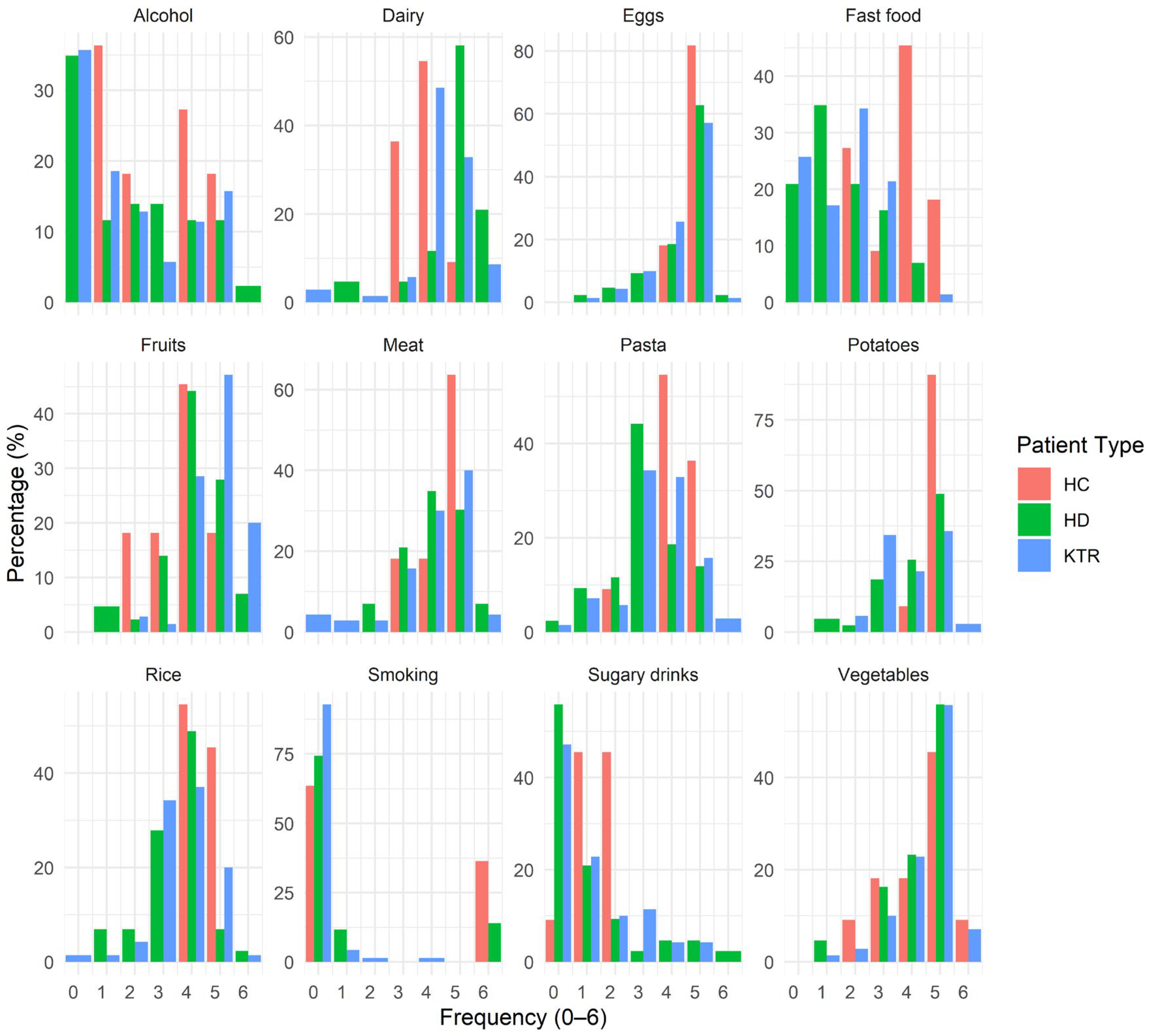

- Clinical status, rather than diet or serum biomarkers, was the primary determinant of microbiome variation.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

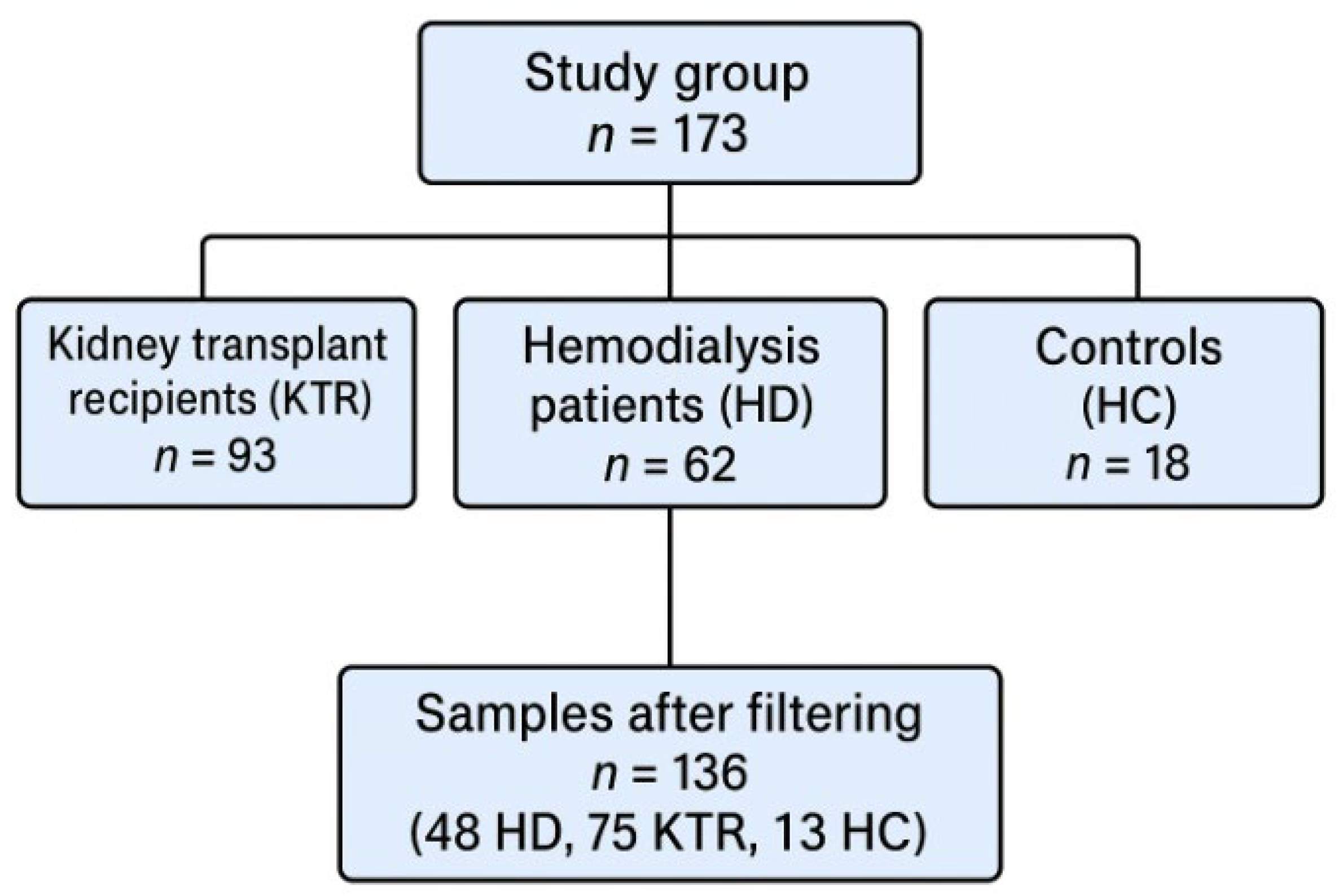

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Baseline Data

2.3. Fecal Microbiota DNA Extraction, Amplification, and Sequencing

2.4. DNA Isolation

2.5. Quantification and Assessment of DNA Purity

2.6. 16S V3–V4 rRNA Gene Sequencing

2.7. Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Anthropometric Parameters

3.2. Bacterial Composition

3.3. Bacterial Diversity

3.4. Impact of Diet

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Taxa Driving Group Separation

4.2. Microbiota Composition Patterns

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti Dey, P. Mechanisms and implications of the gut microbial modulation of intestinal metabolic processes. npj Metab. Health Dis. 2025, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voroneanu, L.; Burlacu, A.; Brinza, C.; Covic, A.; Balan, G.G.; Nistor, I.; Popa, C.; Hogas, S.; Covic, A. Gut Microbiota in Chronic Kidney Disease: From Composition to Modulation towards Better Outcomes—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanholder, R.; De Smet, R.; Glorieux, G.; Argilés, A.; Baurmeister, U.; Brunet, P.; Clark, W.; Cohen, G.; De Deyn, P.P.; Deppisch, R.; et al. Review on uremic toxins: Classification, concentration, and interindividual variability. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 1934–1943, Erratum in: Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaziri, N.D. CKD impairs barrier function and alters microbial flora of the intestine: A major link to inflammation and uremic toxicity. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2012, 21, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, F.C.; Barreto, D.V.; Liabeuf, S.; Meert, N.; Glorieux, G.; Temmar, M.; Choukroun, G.; Vanholder, R.; Massy, Z.A.; European Uremic Toxin Work Group. Serum indoxyl sulfate is associated with vascular disease and mortality in chronic kidney disease patients. Kidney Int. 2009, 76, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, N.D.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Pahl, M.V. Altered intestinal microbial flora and impaired epithelial barrier structure and function in CKD: The nature, mechanisms, consequences and potential treatment. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, N.D.; Yuan, J.; Rahimi, A.; Ni, Z.; Said, H.; Subramanian, V.S. Disintegration of colonic epithelial tight junction in uremia: A likely cause of CKD-associated inflammation. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012, 27, 2686–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, T.; Meyer, T.W.; Hostetter, T.H.; Melamed, M.L.; Parekh, R.S.; Hwang, S.; Banerjee, T.; Coresh, J.; Powe, N.R. Free levels of selected organic solutes and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hemodialysis patients: Results from the Retained Organic Solutes and Clinical Outcomes (ROSCO) Investigators. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Chamieh, C.; Liabeuf, S.; Massy, Z. Uremic Toxins and Cardiovascular Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease: What Have We Learned Recently beyond the Past Findings? Toxins 2022, 14, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chang, X.; Ye, Q.; Gao, Y.; Deng, R. Kidney transplantation and gut microbiota. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gibson, C.M.; Childs-Kean, L.M.; Naziruddin, Z.; Howell, C.K. The alteration of the gut microbiome by immunosuppressive agents used in solid organ transplantation. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2021, 23, e13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarre, P.; Loens, C.; Tamzali, Y.; Barrou, B.; Jaisser, F.; Tourret, J. Immunosuppressive therapy after solid organ transplantation and the gut microbiota: Bidirectional interactions with clinical consequences. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 1014–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikizler, T.A.; Burrowes, J.D.; Byham-Gray, L.D.; Campbell, K.L.; Carrero, J.J.; Chan, W.; Fouque, D.; Friedman, A.N.; Ghaddar, S.; Goldstein-Fuchs, D.J.; et al. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Nutrition in CKD: 2020 Update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 76 (Suppl. S1), S1–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacarean Trandafir, I.C.; Amărandi, R.; Ivanov, I.-C.; Iacob, S.; Muşină, A.-M.; Bărgăoanu, E.-R.; Dimofte, M.-G. The impact of cefuroxime prophylaxis on human intestinal microbiota in surgical oncological patients. Front. Microbiomes 2023, 1, 1092771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation. 2013. Available online: https://support.illumina.com/documents/documentation/chemistry_documentation/16s/16s-metagenomic-library-prep-guide-15044223-b.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; Sankaran, K.; Fukuyama, J.A.; McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S.P. Bioconductor workflow for microbiome data analysis: From raw reads to community analyses. F1000Research 2016, 5, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Văcărean-Trandafir, I.C.; Amărandi, R.-M.; Ivanov, I.C.; Dragoș, L.M.; Mențel, M.; Iacob, Ş.; Muşină, A.-M.; Bărgăoanu, E.-R.; Roată, C.E.; Morărașu, Ș.; et al. Effects of antibiotic prophylaxis on intestinal microbiota in colorectal surgery patients: Results from an Eastern European cross-border stewardship study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 14, 1468645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroceanu, R.P.; Timofte, D.V.; Timofeiov, S.; Vlasceanu, V.I.; Maxim, M.; Miler, A.A.; Iordache, A.G.; Moscalu, R.; Moscalu, M.; Văcărean-Trandafir, I.C.; et al. The Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Gut Microbiota Composition and Diversity: A Longitudinal Analysis Using 16S rRNA Sequencing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, H.; Szöcs, E.; et al. Vegan Community Ecology Package, Version 2.6-2. April 2022.

- Kembel, S.W.; Cowan, P.D.; Helmus, M.R.; Cornwell, W.K.; Morlon, H.; Ackerly, D.D.; Blomberg, S.P.; Webb, C.O. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1463–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohart, F.; Gautier, B.; Singh, A.; Lê Cao, K.-A. mixOmics: An R package for ‘omics feature selection and multiple data integration. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Arze, C.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Schirmer, M.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Poon, T.W.; Andrews, E.; Ajami, N.J.; Bonham, K.S.; Brislawn, C.J.; et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 2019, 569, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, K.; Uchida, N.; Nakanoh, H.; Fukushima, K.; Haraguchi, S.; Kitamura, S.; Wada, J. The Gut-Kidney Axis in Chronic Kidney Diseases. Diagnostics 2024, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Saavedra, S.; Arboleya, S.; Nogacka, A.M.; González Del Rey, C.; Suárez, A.; Diaz, Y.; Gueimonde, M.; Salazar, N.; González, S.; de Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G. Commensal Fecal Microbiota Profiles Associated with Initial Stages of Intestinal Mucosa Damage: A Pilot Study. Cancers 2023, 16, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, H.; Ji, S.; Chen, Z.; Cui, Z.; Chen, J.; Tang, S. Dysbiosis and Implication of the Gut Microbiota in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 646348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbro, I.; Baratta, F.; Angelico, F.; Del Ben, M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and the Kidney: A Review. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotaslou, R.; Nabizadeh, E.; Memar, M.Y.; Law, W.M.H.; Ozma, M.A.; Abdi, M.; Yekani, M.; Kadkhoda, H.; Hosseinpour, R.; Bafadam, S.; et al. The metabolic, protective, and immune functions of Akkermansia muciniphila. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 266, 127245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cuesta-Zuluaga, J.; Mueller, N.T.; Corrales-Agudelo, V.; Velásquez-Mejía, E.P.; Carmona, J.A.; Abad, J.M.; Escobar, J.S. Metformin Is Associated with Higher Relative Abundance of Mucin-Degrading Akkermansia muciniphila and Several Short-Chain Fatty Acid-Producing Microbiota in the Gut. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Liu, J.; Xue, Y.; Kong, X.; Lv, C.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, B. Alteration of gut microbial profile in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Endocrine 2021, 73, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.C.; Wang, Z.; Usyk, M.; Sotres-Alvarez, D.; Daviglus, M.L.; Schneiderman, N.; Talavera, G.A.; Gellman, M.D.; Thyagarajan, B.; Moon, J.Y.; et al. Gut microbiome composition in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos is shaped by geographic relocation, environmental factors, and obesity. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ye, X.; Ding, D.; Lu, Y. Characteristics of the intestinal flora in patients with peripheral neuropathy associated with type 2 diabetes. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Liu, T.; Hu, Y.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, N. Changes in gut microbial community upon chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ajami, N.J.; El-Serag, H.B.; Hair, C.; Graham, D.Y.; White, D.L.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Plew, S.; Kramer, J.; et al. Dietary quality and the colonic mucosa-associated gut microbiome in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surono, I.S.; Wardana, A.A.; Waspodo, P.; Saksono, B.; Verhoeven, J.; Venema, K. Effect of functional food ingredients on gut microbiota in a rodent diabetes model. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 17, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkov, V.A.; Zharikova, A.A.; Demchenko, E.A.; Andrianova, N.V.; Zorov, D.B.; Plotnikov, E.Y. Gut Microbiota as a Source of Uremic Toxins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.; Ooi, L.; Ding, U.; Wu, H.H.L.; Chinnadurai, R. Gut Microbiota in Patients Receiving Dialysis: A Review. Pathogens 2024, 13, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Fan, Y.; Li, A.; Shen, Q.; Wu, J.; Ren, L.; Lu, H.; Ding, S.; Ren, H.; Liu, C.; et al. Alterations of the Human Gut Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmas, V.; Pisanu, S.; Madau, V.; Casula, E.; Deledda, A.; Cusano, R.; Uva, P.; Vascellari, S.; Loviselli, A.; Manzin, A.; et al. Gut microbiota markers associated with obesity and overweight in Italian adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, N.D.; Wong, J.; Pahl, M.; Piceno, Y.M.; Yuan, J.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Ni, Z.; Nguyen, T.H.; Andersen, G.L. Chronic kidney disease alters intestinal microbial flora. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarte, J.C.; Zhang, S.; Nieuwenhuis, L.M.; Gacesa, R.; Knobbe, T.J.; TransplantLines Investigators; De Meijer, V.E.; Damman, K.; Verschuuren, E.A.M.; Gan, T.C.; et al. Multiple indicators of gut dysbiosis predict all-cause and cause-specific mortality in solid organ transplant recipients. Gut 2024, 73, 1650–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, P.; Tariq, R.; Pardi, D.S.; Khanna, S. Effectiveness and Safety of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection in Immunocompromised Patients. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HC (N = 13) | HD (N = 48) | KTR (N = 75) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M:F | 6:7 | 17:31 | 31:44 | 0.473 a |

| Age (years) | M (SD) | 27.2 ± 1.69 | 58.9 (13.2) | 44.8 (10.4) | <0.001 b |

| Range | 23–35 | 33–82 | 24–67 | ||

| Months from intervention | M (SD) | Not applicable | 97 (68.9) | 104 (80.9) | 0.971 c |

| Range | 4–340 | 3–288 | |||

| BSA (m2) | M (SD) | 1.80 (0.21) | 1.82 (0.207) | 1.86 (0.214) | 0.429 b |

| Range | 1.35–2.1 | 1.38–2.2 | 1.49–2.37 | ||

| Albumin (g/L) | M (SD) | 43.6 (4.6) | 41.6 (9.6) | 43.3 (5.07) | 0.197 c |

| Range | 39–48 | 36.7–56 | 26–54 | ||

| CRP (mg/L) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 2.8 (1–4.5) | 6.28 (2.68–12) | 3.1 (2–5) | <0.001 c |

| Range | 1–5.5 | 0.6–73 | 0.2–38 | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | M (SD) | 13.3 (1.93) | 11.2 (1.28) | 13 (1.98) | <0.001 c |

| Range | 11.5–16 | 8.9–16 | 9–17.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Voroneanu, L.; Covic, A.; Iliescu, S.; Baluta, C.V.; Agavriloaei, B.D.; Stefan, A.E.; Amărandi, R.-M.; Văcărean-Trandafir, I.-C.; Ivanov, I.-C.; Covic, A. Distinct Gut Microbiome Signatures in Hemodialysis and Kidney Transplant Populations. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228032

Voroneanu L, Covic A, Iliescu S, Baluta CV, Agavriloaei BD, Stefan AE, Amărandi R-M, Văcărean-Trandafir I-C, Ivanov I-C, Covic A. Distinct Gut Microbiome Signatures in Hemodialysis and Kidney Transplant Populations. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228032

Chicago/Turabian StyleVoroneanu, Luminita, Andreea Covic, Stefan Iliescu, Cezar Valeriu Baluta, Bogdan Dumitru Agavriloaei, Anca Elena Stefan, Roxana-Maria Amărandi, Irina-Cezara Văcărean-Trandafir, Iuliu-Cristian Ivanov, and Adrian Covic. 2025. "Distinct Gut Microbiome Signatures in Hemodialysis and Kidney Transplant Populations" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228032

APA StyleVoroneanu, L., Covic, A., Iliescu, S., Baluta, C. V., Agavriloaei, B. D., Stefan, A. E., Amărandi, R.-M., Văcărean-Trandafir, I.-C., Ivanov, I.-C., & Covic, A. (2025). Distinct Gut Microbiome Signatures in Hemodialysis and Kidney Transplant Populations. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8032. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228032