Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of DDX41 Variants in Korean Patients with Hematologic Malignancies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Targeted NGS

2.3. Classification of Germline DDX41 Variants

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

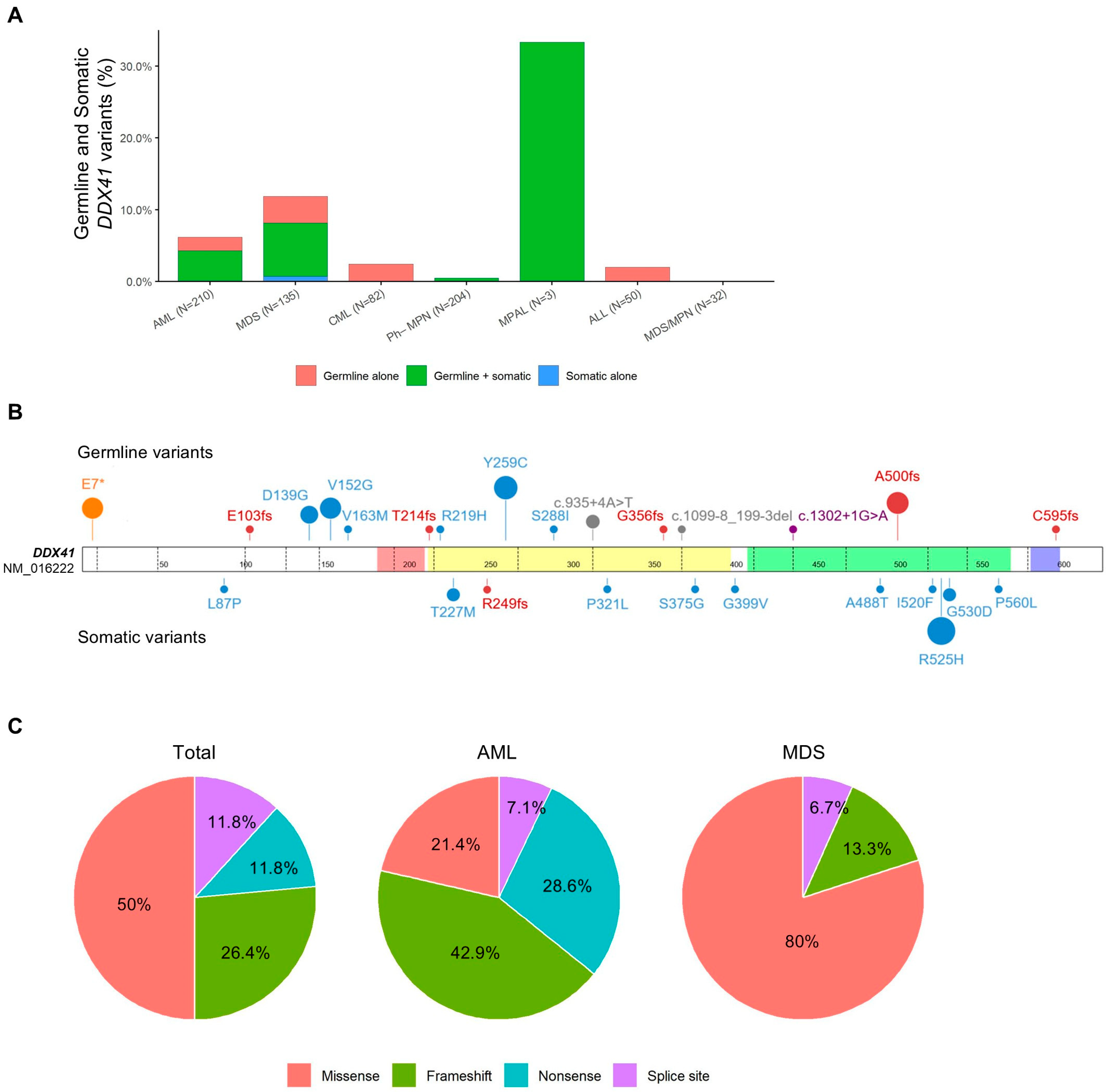

3.1. Overall Frequency of DDX41 Variants

3.2. Clinical and Molecular Characteristics of Patients with Germline DDX41 Variants

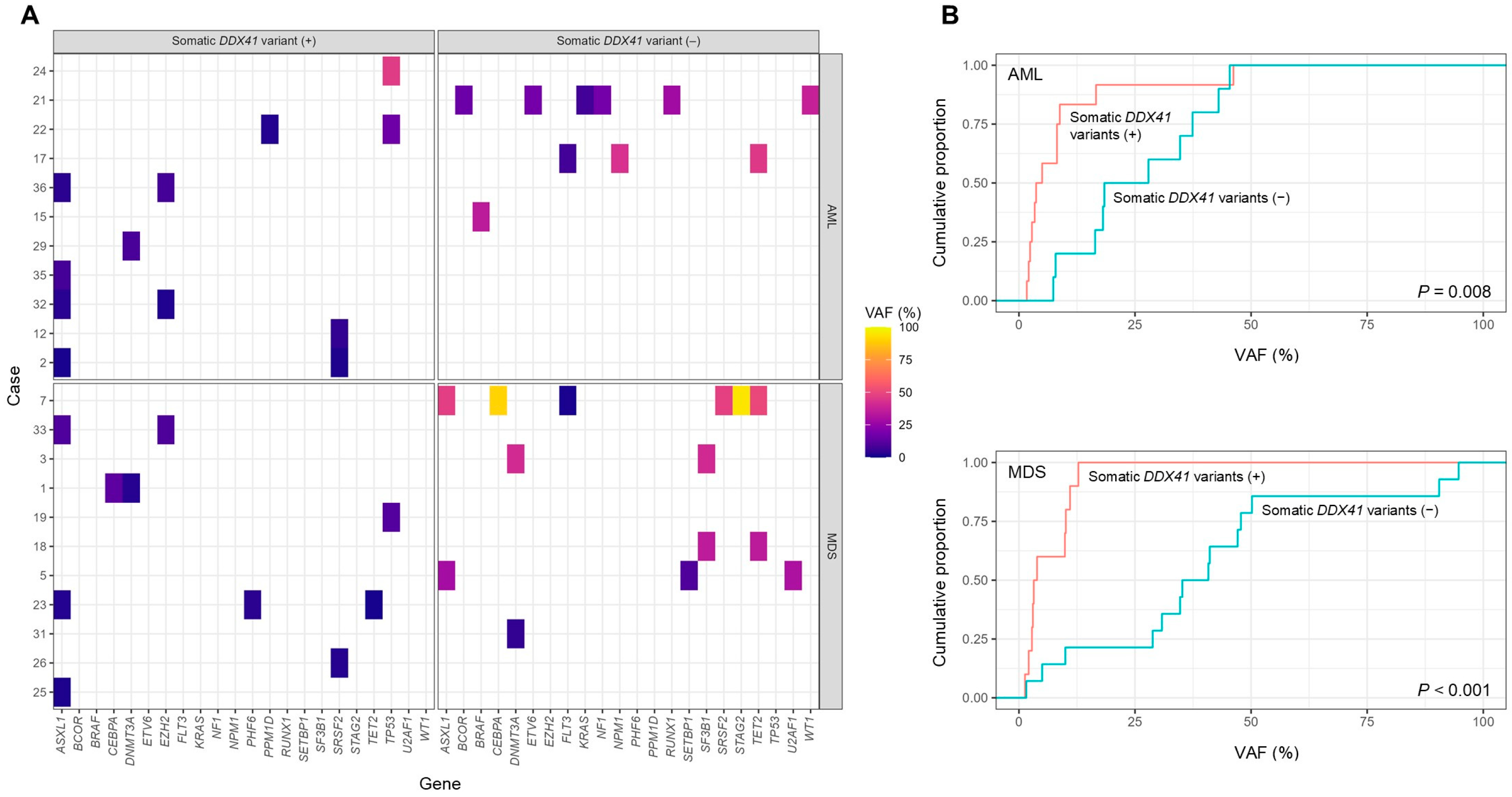

3.3. Co-Occurring Somatic Variants and Their Allele Frequency Patterns

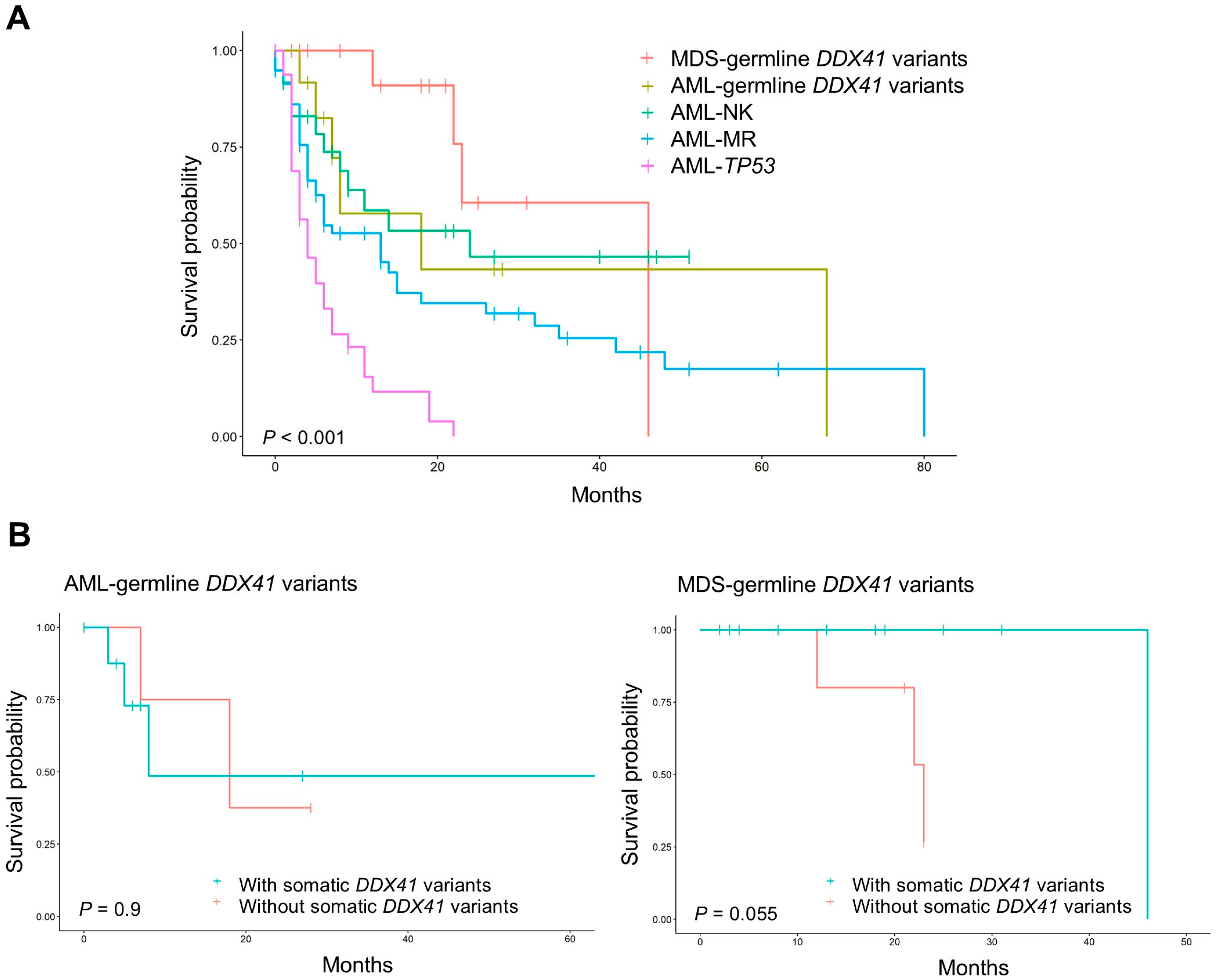

3.4. Survival and Prognosis in AML and MDS with Germline DDX41 Variants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALL | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| AML-MR | Acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplasia-related |

| AML-NK | Acute myeloid leukemia with a normal karyotype |

| AML-TP53 | Acute myeloid leukemia with TP53 mutation |

| CBC | Complete blood counts |

| CML | chronic myeloid leukemia |

| DDX41 | DEAD-box RNA helicase 41 |

| FISH | Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| LPV | Likely pathogenic variant |

| MAF | Minor allele frequency |

| MDS | Myelodysplastic neoplasm |

| MDS/MPN | Myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm |

| MPAL | Mixed phenotype acute leukemia |

| MPN | Myeloproliferative neoplasm |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| PV | Pathogenic variant |

| SNV | Single nucleotide variant |

| VAF | Variant allele frequency |

| VUS | Variant of uncertain significance |

References

- Khoury, J.D.; Solary, E.; Abla, O.; Akkari, Y.; Alaggio, R.; Apperley, J.F.; Bejar, R.; Berti, E.; Busque, L.; Chan, J.K.C.; et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1703–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polprasert, C.; Schulze, I.; Sekeres, M.A.; Makishima, H.; Przychodzen, B.; Hosono, N.; Singh, J.; Padgett, R.A.; Gu, X.; Phillips, J.G.; et al. Inherited and Somatic Defects in DDX41 in Myeloid Neoplasms. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreou, A.Z. DDX41: A multifunctional DEAD-box protein involved in pre-mRNA splicing and innate immunity. Biol. Chem. 2021, 402, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Ong, F.; Sasaki, K. Current Understanding of DDX41 Mutations in Myeloid Neoplasms. Cancers 2023, 15, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badar, T.; Nanaa, A.; Foran, J.M.; Viswanatha, D.; Al-Kali, A.; Lasho, T.; Finke, C.; Alkhateeb, H.B.; He, R.; Gangat, N.; et al. Clinical and molecular correlates of somatic and germline DDX41 variants in patients and families with myeloid neoplasms. Haematologica 2023, 108, 3033–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; White, T.; Xie, W.; Cui, W.; Peker, D.; Zeng, G.; Wang, H.Y.; Vagher, J.; Brown, S.; Williams, M.; et al. AML with germline DDX41 variants is a clinicopathologically distinct entity with an indolent clinical course and favorable outcome. Leukemia 2022, 36, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, J.; Chlon, T.M. Germline DDX41 mutations in myeloid neoplasms: The current clinical and molecular understanding. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2024, 32, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurstein, S.; Hahn, C.N.; Mehta, N.; Godley, L.A. A practical guide to interpreting germline variants that drive hematopoietic malignancies, bone marrow failure, and chronic cytopenias. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 931–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, H.; Hirata, M. Evaluation of the pathogenic potential of germline DDX41 variants in hematopoietic neoplasms using the ACMG/AMP guidelines. Int. J. Hematol. 2024, 119, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Brown, S.; Williams, M.; White, T.; Xie, W.; Cui, W.; Peker, D.; Lei, L.; Kunder, C.A.; Wang, H.-Y.; et al. The genetic landscape of germline DDX41 variants predisposing to myeloid neoplasms. Blood 2022, 140, 716–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maierhofer, A.; Mehta, N.; Chisholm, R.A.; Hutter, S.; Baer, C.; Nadarajah, N.; Pohlkamp, C.; Thompson, E.R.; James, P.A.; Kern, W.; et al. The clinical and genomic landscape of patients with DDX41 variants identified during diagnostic sequencing. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 7346–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Starczynowski, D.T. Are DDX41 variants of unknown significance and pathogenic variants created equal? Haematologica 2023, 108, 2883–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, S.H.; Campo, E.; Harris, N.L.; Jaffe, E.S.; Pileri, S.A.; Stein, H.; Thiele, J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Revised 4th ed.; IARC: Lyon, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alaggio, R.; Amador, C.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Attygalle, A.D.; Araujo, I.B.O.; Berti, E.; Bhagat, G.; Borges, A.M.; Boyer, D.; Calaminici, M.; et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1720–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, H.N.; Kwon, J.A.; Yoon, S.Y.; Jeon, M.J.; Yu, E.S.; Kim, D.S.; Choi, C.W.; Yoon, J. Implications of the 5(th) Edition of the World Health Organization Classification and International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasm in Myelodysplastic Syndrome With Excess Blasts and Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Ann. Lab. Med. 2023, 43, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Kim, B.; Jang, J.H.; Jung, C.W.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, H.Y. Rare Non-Cryptic NUP98 Rearrangements Associated With Myeloid Neoplasms and Their Poor Prognostic Impact. Ann. Lab. Med. 2025, 45, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sébert, M.; Passet, M.; Raimbault, A.; Rahmé, R.; Raffoux, E.; Sicre de Fontbrune, F.; Cerrano, M.; Quentin, S.; Vasquez, N.; Da Costa, M.; et al. Germline DDX41 mutations define a significant entity within adult MDS/AML patients. Blood 2019, 134, 1441–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, R.M.; Kim, J.; Haley, J.S.; Ramos, M.L.; Mirshahi, U.L.; Carey, D.J.; Stewart, D.R.; McReynolds, L.J. Genome-first determination of the prevalence and penetrance of eight germline myeloid malignancy predisposition genes: A study of two population-based cohorts. Leukemia 2024, 39, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusne, Y.; Badar, T.; Lasho, T.; Marando, L.; Mangaonkar, A.A.; Finke, C.; Foran, J.M.; Al-Kali, A.; Palmer, J.; Arana Yi, C.; et al. Prevalence of cytopenia(s) and somatic variants in patients with DDX41 mutant germline predisposition syndrome. Br. J. Haematol. 2025, 206, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Tayoun, A.N.; Pesaran, T.; DiStefano, M.T.; Oza, A.; Rehm, H.L.; Biesecker, L.G.; Harrison, S.M.; ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation Working, G. Recommendations for interpreting the loss of function PVS1 ACMG/AMP variant criterion. Hum. Mutat. 2018, 39, 1517–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, N.M.; Rothstein, J.H.; Pejaver, V.; Middha, S.; McDonnell, S.K.; Baheti, S.; Musolf, A.; Li, Q.; Holzinger, E.; Karyadi, D.; et al. REVEL: An Ensemble Method for Predicting the Pathogenicity of Rare Missense Variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 99, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataller, A.; Loghavi, S.; Gerstein, Y.; Bazinet, A.; Sasaki, K.; Chien, K.S.; Hammond, D.; Montalban-Bravo, G.; Borthakur, G.; Short, N.; et al. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of patients with myeloid malignancies and DDX41 variants. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 1780–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Z.; Han, B. Clinical features of DDX41 mutation-related diseases: A systematic review with individual patient data. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2021, 12, 20406207211032433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.J.; Cho, Y.U.; Hur, E.H.; Jang, S.; Kim, N.; Park, H.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, S.H.; Hwang, S.H.; et al. Unique ethnic features of DDX41 mutations in patients with idiopathic cytopenia of undetermined significance, myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2022, 107, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewinsohn, M.; Brown, A.L.; Weinel, L.M.; Phung, C.; Rafidi, G.; Lee, M.K.; Schreiber, A.W.; Feng, J.; Babic, M.; Chong, C.E.; et al. Novel germ line DDX41 mutations define families with a lower age of MDS/AML onset and lymphoid malignancies. Blood 2016, 127, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makishima, H.; Saiki, R.; Nannya, Y.; Korotev, S.; Gurnari, C.; Takeda, J.; Momozawa, Y.; Best, S.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Yoshizato, T.; et al. Germ line DDX41 mutations define a unique subtype of myeloid neoplasms. Blood 2023, 141, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, A.E.; Routbort, M.J.; DiNardo, C.D.; Bueso-Ramos, C.E.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Khoury, J.D.; Thakral, B.; Zuo, Z.; Yin, C.C.; Loghavi, S.; et al. DDX41 mutations in myeloid neoplasms are associated with male gender, TP53 mutations and high-risk disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Wang, X.; Yao, M.; Tao, Y.; Han, Y. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of DDX41 mutation in myeloid neoplasms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Hematol. 2025, 104, 2581–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | AML (N = 13) | MDS (N = 15) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, yrs (range) | 68 (48–76) | 69 (50–86) | 0.406 |

| Male, N (%) | 9 (69.2) | 11 (73.3) | 1.000 |

| Median Hb, g/dL (range) | 8.3 (5.7–11.9) | 8.8 (5.6–11.5) | 0.747 |

| Median WBC, ×109/L (range) | 1.72 (1.08–23.41) | 2.21 (0.97–31.2) | 0.213 |

| Median PLT, ×109/L (range) | 47 (19–114) | 101.5 (34–404) | 0.025 |

| Median BM blasts, % (range) | 30.0 (19.8–92.3) | 2.9 (0–18.0) | <0.001 |

| Median BM cellularity, % (range) | 20.0 (10–90) | 22.5 (15–100) | 0.950 |

| Normal karyotype, N (%) | 10 (76.9) | 12 (80.0) | 1.000 |

| Any somatic mutation, N (%) | 12 (92.3) | 15 (100.0) | 0.464 |

| Somatic DDX41 mutation | 9 (69.2) | 10 (66.7) | 1.000 |

| Other somatic mutation (excluding DDX41) | 11 (84.6) | 11 (73.3) | 0.646 |

| WHO classification, N (%) | |||

| AML-MR | 9 (69.2) | ||

| AML with KMT2A rearrangement | 1 (7.7) | ||

| AML with NPM1 mutation | 1 (7.7) | ||

| AML-NOS | 2 (15.4) | ||

| MDS-LB | 7 (46.7) | ||

| MDS-LB-SF3B1 | 1 (6.7) | ||

| MDS-del(5q) | 1 (6.7) | ||

| MDS-IB1 | 3 (20.0) | ||

| MDS-IB2 | 3 (20.0) | ||

| Allogeneic HSCT, N (%) | 3 (23.1) | 3 (20.0) | 1.000 |

| Death, N (%) | 6 (46.2) | 4 (26.7) | 0.433 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, B.; Choi, D.-H.; Jang, J.H.; Jung, C.W.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, H.-Y. Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of DDX41 Variants in Korean Patients with Hematologic Malignancies. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7999. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227999

Kim B, Choi D-H, Jang JH, Jung CW, Kim H-J, Kim H-Y. Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of DDX41 Variants in Korean Patients with Hematologic Malignancies. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):7999. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227999

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Boram, Dae-Ho Choi, Jun Ho Jang, Chul Won Jung, Hee-Jin Kim, and Hyun-Young Kim. 2025. "Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of DDX41 Variants in Korean Patients with Hematologic Malignancies" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 7999. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227999

APA StyleKim, B., Choi, D.-H., Jang, J. H., Jung, C. W., Kim, H.-J., & Kim, H.-Y. (2025). Clinical and Molecular Spectrum of DDX41 Variants in Korean Patients with Hematologic Malignancies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 7999. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227999