Endometriosis During Adolescence: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Search Methodology

2. Epidemiology

Risk Factors

3. Clinical Presentation

Severity and Progression

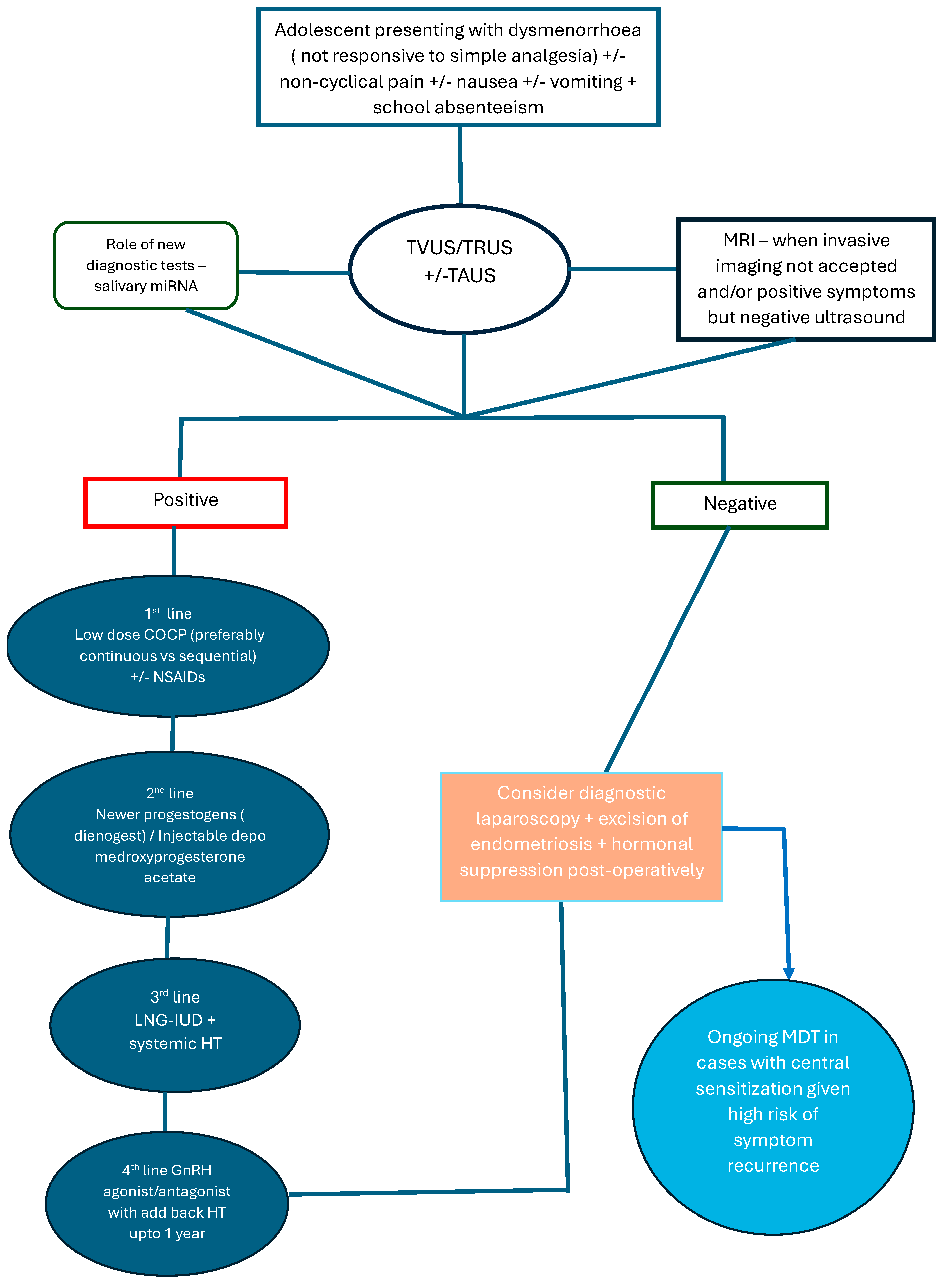

4. Diagnosis

The Paradigm Shift in Diagnosis

5. Treatment

5.1. Medical Management

5.2. Surgical Treatment

6. Conclusions

7. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leibson, C.L.; Good, A.E.; Hass, S.L.; Ransom, J.; Yawn, B.P.; O’Fallon, W.M.; Melton, L.J. Incidence and characterization of diagnosed endometriosis in a geographically defined population. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 82, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upson, K.; Sathyanarayana, S.; Scholes, D.; Holt, V.L. Early-life factors and endometriosis risk. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, 964–971.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, E.C.; Kho, K.A.; Morozov, V.V.; Kearney, S.; Zurawin, J.L.; Nezhat, C.H. Endometriosis in Adolescents. In Endometriosis in Adolescents: A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosis and Management; Nezhat, C.H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- DiVasta, A.D.; Vitonis, A.F.; Laufer, M.R.; Missmer, S.A. Spectrum of symptoms in women diagnosed with endometriosis during adolescence vs adulthood. Am. J Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 324.e1–324.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghese, B.; Zondervan, K.T.; Abrao, M.S.; Chapron, C.; Vaiman, D. Recent insights on the genetics and epigenetics of endometriosis. Clin. Genet. 2017, 91, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Barlow, D.; Kennedy, S. Implantation versus infiltration: The Sampson versus the endometriotic disease theory. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 1999, 47 (Suppl. S1), 3–9, discussion 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, F.G.; Giorgi, M.; D’Abate, C.; Colombi, I.; Ginetti, A.; Cannoni, A.; Fedele, F.; Exacoustos, C.; Centini, G.; Zupi, E.; et al. Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis in Adolescence: Early Diagnosis and Possible Prevention of Disease Progression. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskenazi, B.; Warner, M.L. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North. Am. 1997, 24, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brosens, I.; Gordts, S.; Benagiano, G. Endometriosis in adolescents is a hidden, progressive and severe disease that deserves attention, not just compassion. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 2026–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinaii, N.; Cleary, S.D.; Ballweg, M.L.; Nieman, L.K.; Stratton, P. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: A survey analysis. Hum. Reprod. 2002, 17, 2715–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millischer, A.E.; Santulli, P.; Da Costa, S.; Bordonne, C.; Cazaubon, E.; Marcellin, L.; Chapron, C. Adolescent endometriosis: Prevalence increases with age on magnetic resonance imaging scan. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, F.G.; Lazzeri, L.; Conway, F.; Siciliano, T.; Pietropolli, A.; Piccione, E.; Solima, E.; Centini, G.; Zupi, E.; Exacoustos, C. Adolescence and endometriosis: Symptoms, ultrasound signs and early diagnosis. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 114, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, I.J.; Pinto, P.V.; Bernardes, J. Noninvasive Diagnosis of Endometriosis in Adolescents and Young Female Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2025, 38, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerriero, S.; Condous, G.; van den Bosch, T.; Valentin, L.; Leone, F.P.G.; Van Schoubroeck, D.; Exacoustos, C.; Installé, A.J.F.; Martins, W.P.; Abrao, M.S.; et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: A consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 48, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, E.B.; Rijkers, A.C.M.; Hoppenbrouwers, K.; Meuleman, C.; D’Hooghe, T.M. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: A systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2013, 19, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowlut-McElroy, T.; Strickland, J.L. Endometriosis in adolescents. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 29, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sanctis, V.; Matalliotakis, M.; Soliman, A.T.; Elsefdy, H.; Di Maio, S.; Fiscina, B. A focus on the distinctions and current evidence of endometriosis in adolescents. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 51, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missmer, S.A.; Hankinson, S.E.; Spiegelman, D.; Barbieri, R.L.; Marshall, L.M.; Hunter, D.J. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 160, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapron, C.; Lafay-Pillet, M.-C.; Monceau, E.; Borghese, B.; Ngô, C.; Souza, C.; de Ziegler, D. Questioning patients about their adolescent history can identify markers associated with deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis†. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüest, A.; Limacher, J.M.; Dingeldein, I.; Siegenthaler, F.; Vaineau, C.; Wilhelm, I.; Mueller, M.D.; Imboden, S. Pain Levels of Women Diagnosed with Endometriosis: Is There a Difference in Younger Women? J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2023, 36, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.; Vincent, K.; Hirst, J.; Hippisley-Cox, J. Incidence of menstrual symptoms suggestive of possible endometriosis in adolescents: And variance in these by ethnicity and socio-economic status. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2024, 74 (Suppl. S1), bjgp24X737685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, R.; Stratton, P.; Cleary, S.D.; Ballweg, M.L.; Sinaii, N. Diagnostic experience among 4,334 women reporting surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 91, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoi, I.; Somigliana, E.; Riparini, J.; Ronzoni, S.; Vigano’, P.; Candiani, M. High Rate of Endometriosis Recurrence in Young Women. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2011, 24, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, M.R. Helping “Adult Gynecologists” Diagnose and Treat Adolescent Endometriosis: Reflections on My 20 Years of Personal Experience. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2011, 24, S13–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsonis, O.; Barmpalia, Z.; Gkrozou, F.; Chandraharan, E.; Pandey, S.; Siafaka, V.; Paschopoulos, M. Endometriosis in adolescence: Early manifestation of the traditional disease or a unique variant? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 247, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasamoto, N.; Shafrir, A.L.; Wallace, B.M.; Vitonis, A.F.; Fraer, C.J.; Sadler Gallagher, J.; DePari, M.; Ghiasi, M.; Laufer, M.R.; Sieberg, C.B.; et al. Trends in pelvic pain symptoms over 2 years of follow-up among adolescents and young adults with and without endometriosis. Pain 2023, 164, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, D.; Raffone, A.; Renzulli, F.; Sanna, G.; Raspollini, A.; Bertoldo, L.; Maletta, M.; Lenzi, J.; Rovero, G.; Travaglino, A.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Central Sensitization in Women with Endometriosis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 73–80.e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, D.; Brick, E.; East, M.C.; Johnson, N. Endometriosis education in schools: A New Zealand model examining the impact of an education program in schools on early recognition of symptoms suggesting endometriosis. Aust. N. Zealand J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 57, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moumane, K.; Idri, A. Mobile applications for endometriosis management functionalities: Analysis and potential. Sci. Afr. 2023, 21, e01833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, P.; Gupta, S.; Gieg, S. Endometriosis in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain Disord. 2017, 9, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stochino-Loi, E.; Millochau, J.-C.; Angioni, S.; Touleimat, S.; Abo, C.; Chanavaz-Lacheray, I.; Hennetier, C.; Roman, H. Relationship between Patient Age and Disease Features in a Prospective Cohort of 1560 Women Affected by Endometriosis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, M.L.; Seong, S.J.; Bae, J.W.; Cho, Y.J. Recurrence of Ovarian Endometrioma in Adolescents after Conservative, Laparoscopic Cyst Enucleation. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2017, 30, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.D.; Thillet, E.; Lindemann, J. Clinical characteristics of adolescent endometriosis. J. Adolesc. Health 1993, 14, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Fedele, L.; Aimi, G.; Pietropaolo, G.; Consonni, D.; Crosignani, P.G. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: A multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 22, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyholt, D.R.; Low, S.K.; Anderson, C.A.; Painter, J.N.; Uno, S.; Morris, A.P.; MacGregor, S.; Gordon, S.D.; Henders, A.K.; Martin, N.G.; et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies new endometriosis risk loci. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridoğan, E. Endometriosis in Teenagers. Women’s Health 2015, 11, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Meuleman, C.; Demeyere, S.; Lesaffre, E.; Cornillie, F.J. Suggestive evidence that pelvic endometriosis is a progressive disease, whereas deeply infiltrating endometriosis is associated with pelvic pain. Fertil. Steril. 1991, 55, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, J.S.; DiVasta, A.D.; Vitonis, A.F.; Sarda, V.; Laufer, M.R.; Missmer, S.A. The Impact of Endometriosis on Quality of Life in Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghai, V.; Haider, J.; Fevzi, S.; Pat, H.; and Kent, A. Diagnostic delay for superficial and deep endometriosis in the United Kingdom. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 40, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 760 Summary: Dysmenorrhea and Endometriosis in the Adolescent. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 1517–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, K.; Lowton, K.; Wright, J. What’s the delay? A qualitative study of women’s experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 86, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A.F.; Chor, J. Factors Influencing Adolescent and Young Adults’ First Pelvic Examination Experiences: A Qualitative Study. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2019, 32, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.Y.; Laufer, M.R.; King, C.R.; Lee, T.T.M.; Einarsson, J.I.; Tyson, N. Evaluation and Management of Endometriosis in the Adolescent. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 143, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.; Copley, S.; Morris, J.; Lindsell, D.; Golding, S.; Kennedy, S. A systematic review of the accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 20, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exacoustos, C.; Martire, F.G.; Lazzeri, L.; Zupi, E. Utility of Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Adolescents Suspected of Endometriosis. In Endometriosis in Adolescents: A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosis and Management; Nezhat, C.H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 333–355. [Google Scholar]

- Ohba, T.; Mizutani, H.; Maeda, T.; Matsuura, K.; Okamura, H. Endometriosis: Evaluation of endometriosis in uterosacral ligaments by transrectal ultrasonography. Hum. Reprod. 1996, 11, 2014–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazot, M.; Thomassin, I.; Hourani, R.; Cortez, A.; Darai, E. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for deep pelvic endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 24, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampl, B.S.; King, C.R.; Attaran, M.; Feldman, M.K. Adolescent endometriosis: Clinical insights and imaging considerations. Abdom. Radiol. 2025, 50, 4844–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrassani, M.; Guerriero, S.; Pascual, M.Á.; Ajossa, S.; Graupera, B.; Pagliuca, M.; Podgaec, S.; Camargos, E.; Vieira de Oliveira, Y.; Alcázar, J.L. Superficial Endometriosis at Ultrasound Examination—A Diagnostic Criteria Proposal. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, S.; Saba, L.; Pascual, M.A.; Ajossa, S.; Rodriguez, I.; Mais, V.; Alcazar, J.L. Transvaginal ultrasound vs magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosing deep infiltrating endometriosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 51, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Tapmeier, T.T.; Rahmioglu, N.; Kirtley, S.; Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M. The miRNA Mirage: How Close Are We to Finding a Non-Invasive Diagnostic Biomarker in Endometriosis? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendifallah, S.; Suisse, S.; Puchar, A.; Delbos, L.; Poilblanc, M.; Descamps, P.; Golfier, F.; Jornea, L.; Bouteiller, D.; Touboul, C.; et al. Salivary MicroRNA Signature for Diagnosis of Endometriosis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendifallah, S.; Dabi, Y.; Suisse, S.; Delbos, L.; Spiers, A.; Poilblanc, M.; Golfier, F.; Jornea, L.; Bouteiller, D.; Fernandez, H.; et al. Validation of a Salivary miRNA Signature of Endometriosis—Interim Data. NEJM Evid. 2023, 2, EVIDoa2200282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasamoto, N.; Ngo, L.; Vitonis, A.F.; Dillon, S.T.; Prasad, P.; Laufer, M.R.; As-Sanie, S.; Schrepf, A.; Missmer, S.A.; Libermann, T.A.; et al. Plasma proteins and persistent postsurgical pelvic pain among adolescents and young adults with endometriosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 231, 240.e1–240.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.R.; Westhoff, C.; O’Connell, K.; Gallagher, N. Oral contraceptives for dysmenorrhea in adolescent girls: A randomized trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 106, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.D.; Dong, L.; Merz, M.; Kirsch, B.; Francuski, M.; Böttcher, B.; Roman, H.; Suvitie, P.; Hlavackova, O.; Gude, K.; et al. Dienogest 2 mg Daily in the Treatment of Adolescents with Clinically Suspected Endometriosis: The VISanne Study to Assess Safety in ADOlescents. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2017, 30, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laufer, M.R.; Sanfilippo, J.; Rose, G. Adolescent endometriosis: Diagnosis and treatment approaches. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2003, 16 (Suppl. S3), S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, J.Y.; Milliren, C.E.; DiVasta, A.D. Continuation of the Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine Device Among Adolescents with Endometriosis. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2025, 38, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler Gallagher, J.; Feldman, H.A.; Stokes, N.A.; Laufer, M.R.; Hornstein, M.D.; Gordon, C.M.; DiVasta, A.D. The Effects of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Combined with Add-Back Therapy on Quality of Life for Adolescents with Endometriosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2017, 30, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, L.C.; As-Sanie, S.; Arjona Ferreira, J.C.; Becker, C.M.; Abrao, M.S.; Lessey, B.A.; Brown, E.; Dynowski, K.; Wilk, K.; Li, Y.; et al. Once daily oral relugolix combination therapy versus placebo in patients with endometriosis-associated pain: Two replicate phase 3, randomised, double-blind, studies (SPIRIT 1 and 2). Lancet 2022, 399, 2267–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, M.R.; Einarsson, J.I. Surgical Management of Superficial Peritoneal Adolescent Endometriosis. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2019, 32, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candiani, M.; Ottolina, J.; Schimberni, M.; Tandoi, I.; Bartiromo, L.; Ferrari, S. Recurrence Rate after “One-Step” CO2 Fiber Laser Vaporization versus Cystectomy for Ovarian Endometrioma: A 3-Year Follow-up Study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.O.; Missmer, S.A.; Laufer, M.R. The effect of combined surgical-medical intervention on the progression of endometriosis in an adolescent and young adult population. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2009, 22, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, J.D. Adolescent endometriosis in the Waikato region of New Zealand--a comparative cohort study with a mean follow-up time of 2.6 years. Aust. N. Zealand J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2010, 50, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, P., Jr.; Sinervo, K.; Winer, W.; Albee, R.B., Jr. Complete laparoscopic excision of endometriosis in teenagers: Is postoperative hormonal suppression necessary? Fertil. Steril. 2011, 95, 1909–1912, 1912.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.Y. Dysmenorrhea and Endometriosis in Adolescents. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North. Am. 2024, 51, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- As-Sanie, S.; Kim, J.; Schmidt-Wilcke, T.; Sundgren, P.C.; Clauw, D.J.; Napadow, V.; Harris, R.E. Functional Connectivity Is Associated with Altered Brain Chemistry in Women with Endometriosis-Associated Chronic Pelvic Pain. J. Pain 2016, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.W.; Lee, D.Y.; Yoon, B.K.; Choi, D. The Efficacy of Postoperative Cyclic Oral Contraceptives after Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Therapy to Prevent Endometrioma Recurrence in Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2017, 30, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mathias, C.R.; Condous, G.; Espada Vaquero, M. Endometriosis During Adolescence: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7755. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217755

Mathias CR, Condous G, Espada Vaquero M. Endometriosis During Adolescence: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7755. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217755

Chicago/Turabian StyleMathias, Caroline Ruth, George Condous, and Mercedes Espada Vaquero. 2025. "Endometriosis During Adolescence: A Narrative Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7755. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217755

APA StyleMathias, C. R., Condous, G., & Espada Vaquero, M. (2025). Endometriosis During Adolescence: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7755. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217755