Is the EMpressin Injection in ENDOmetrioma eXcision Surgery Useful? The EMENDOX Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

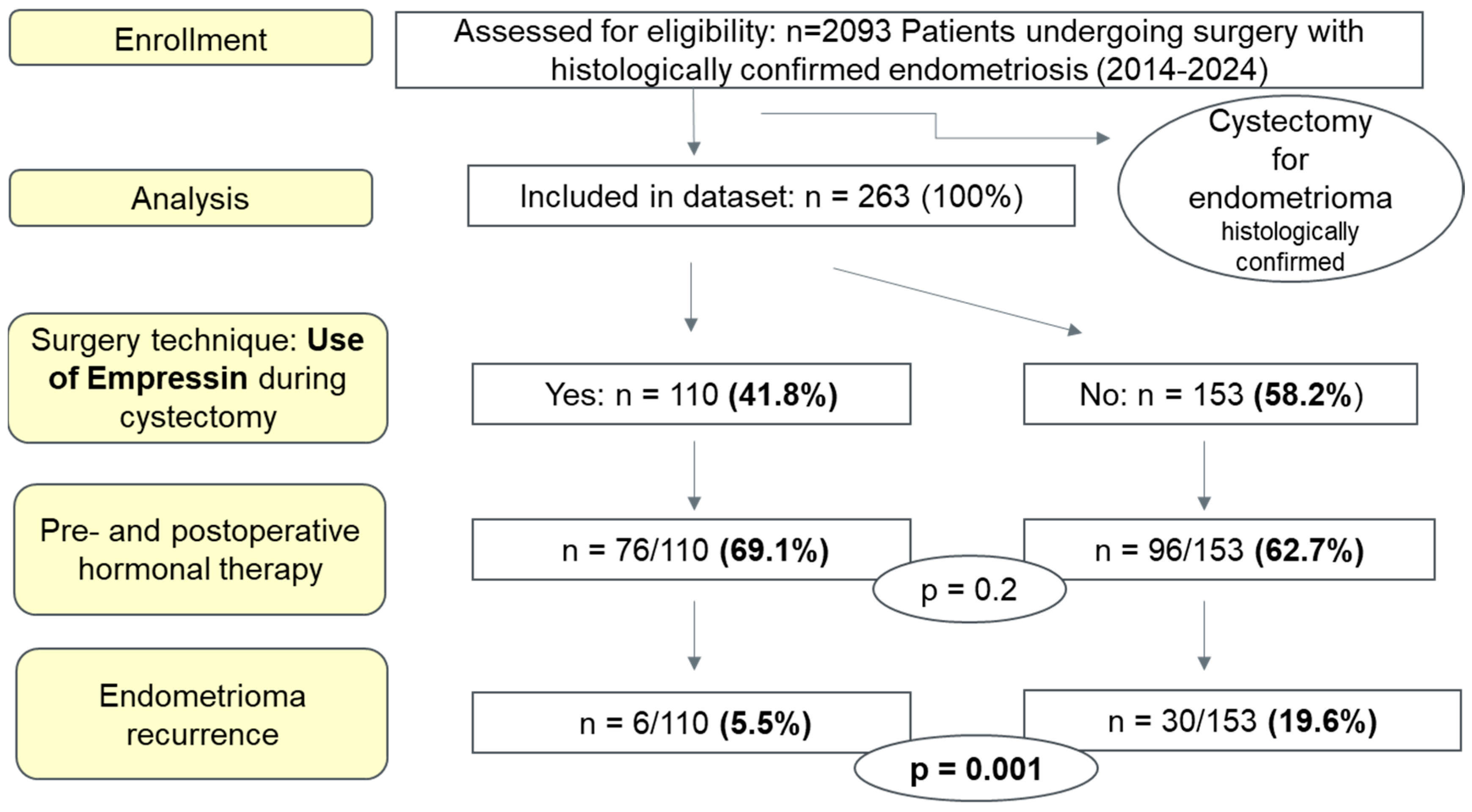

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

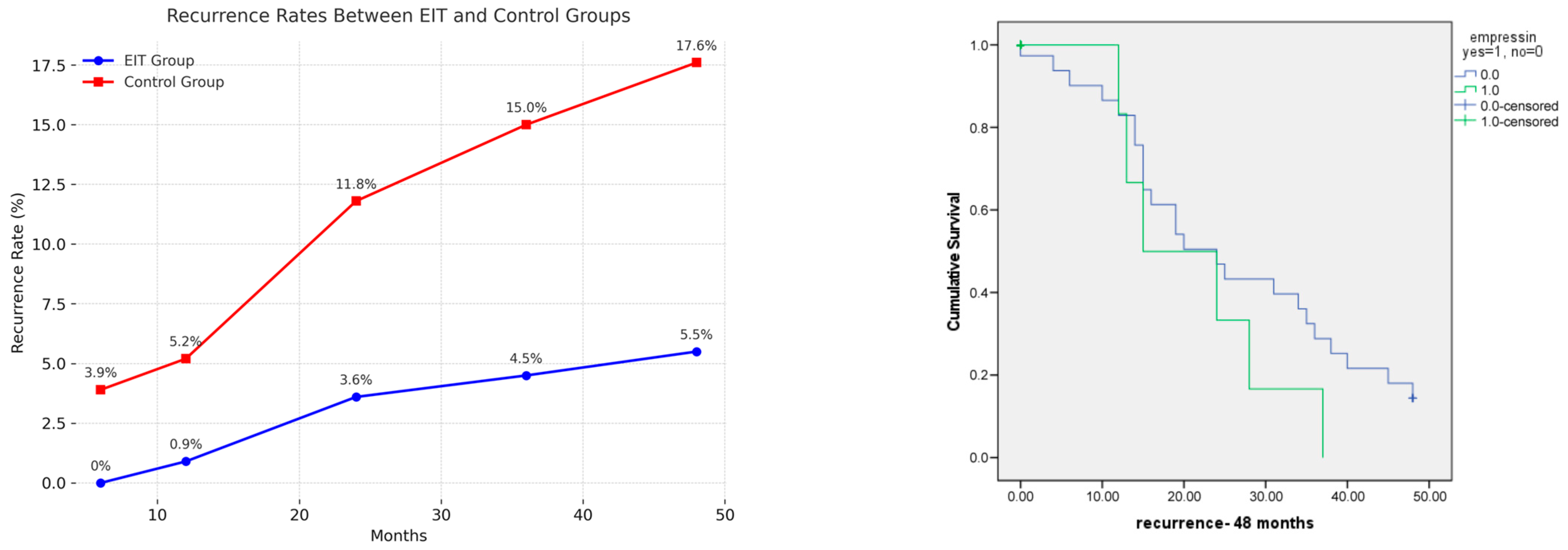

3. Results

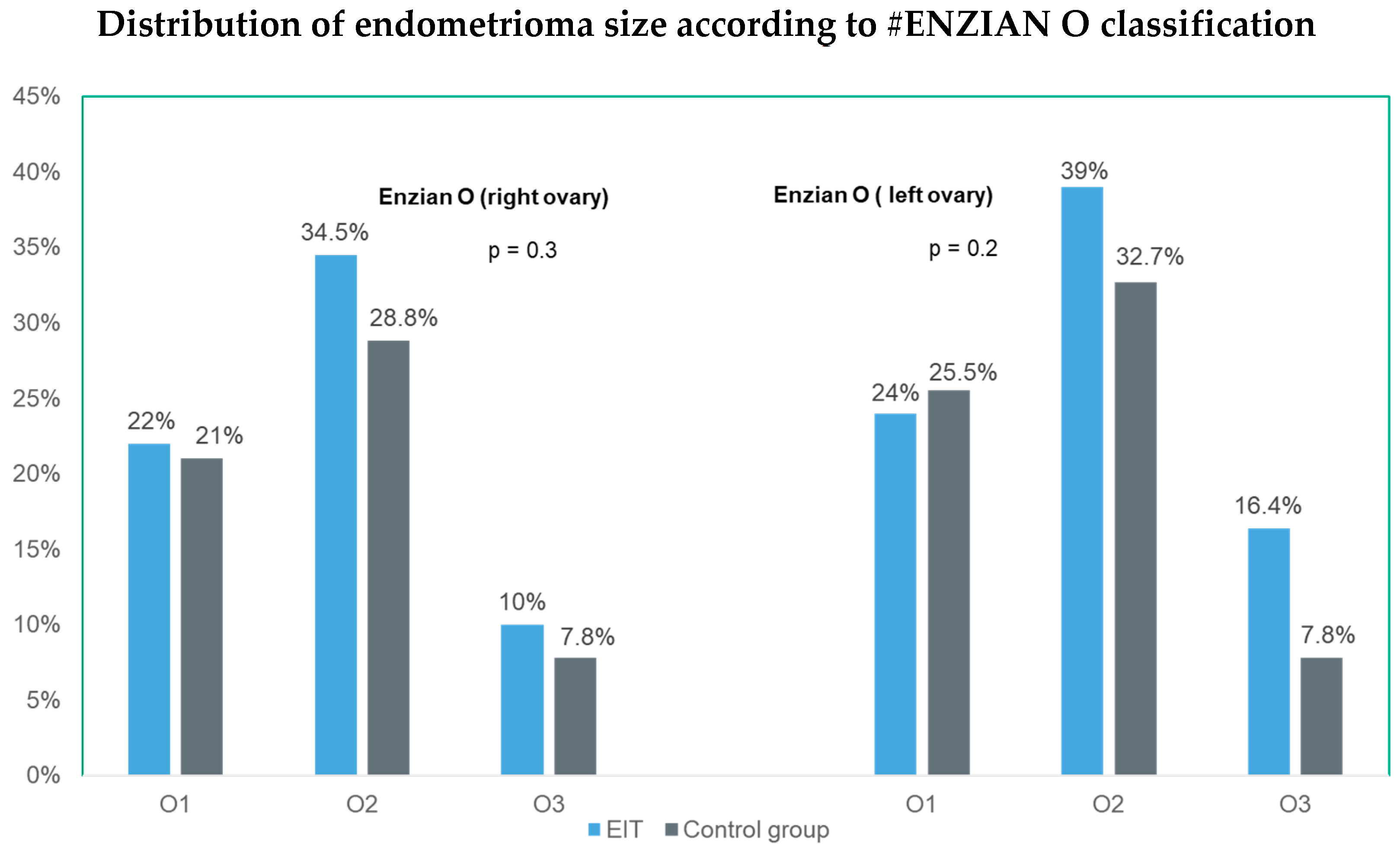

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Surgical Procedure and Operative Time

3.3. Surgical and Postoperative Outcomes

4. Discussion

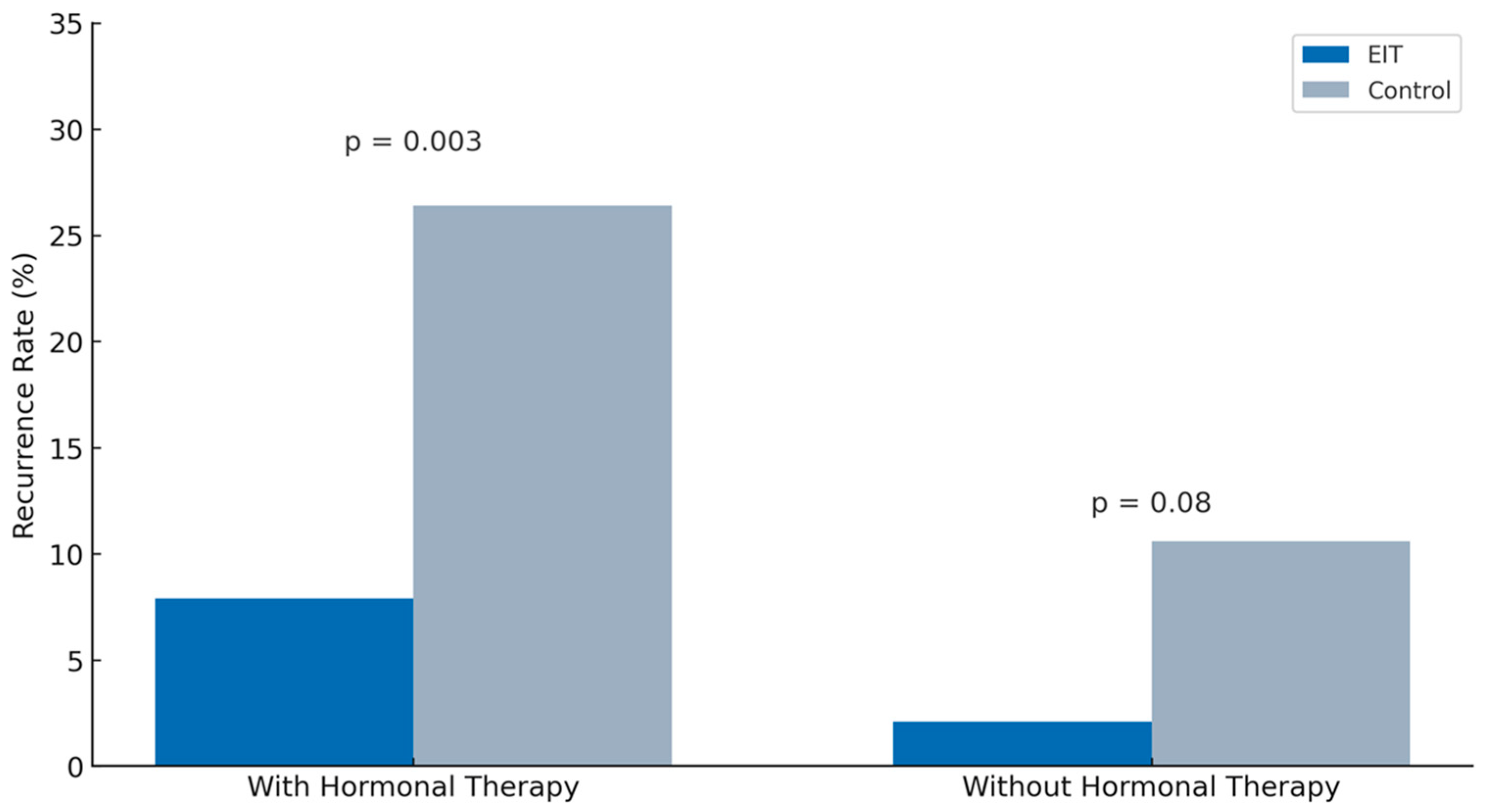

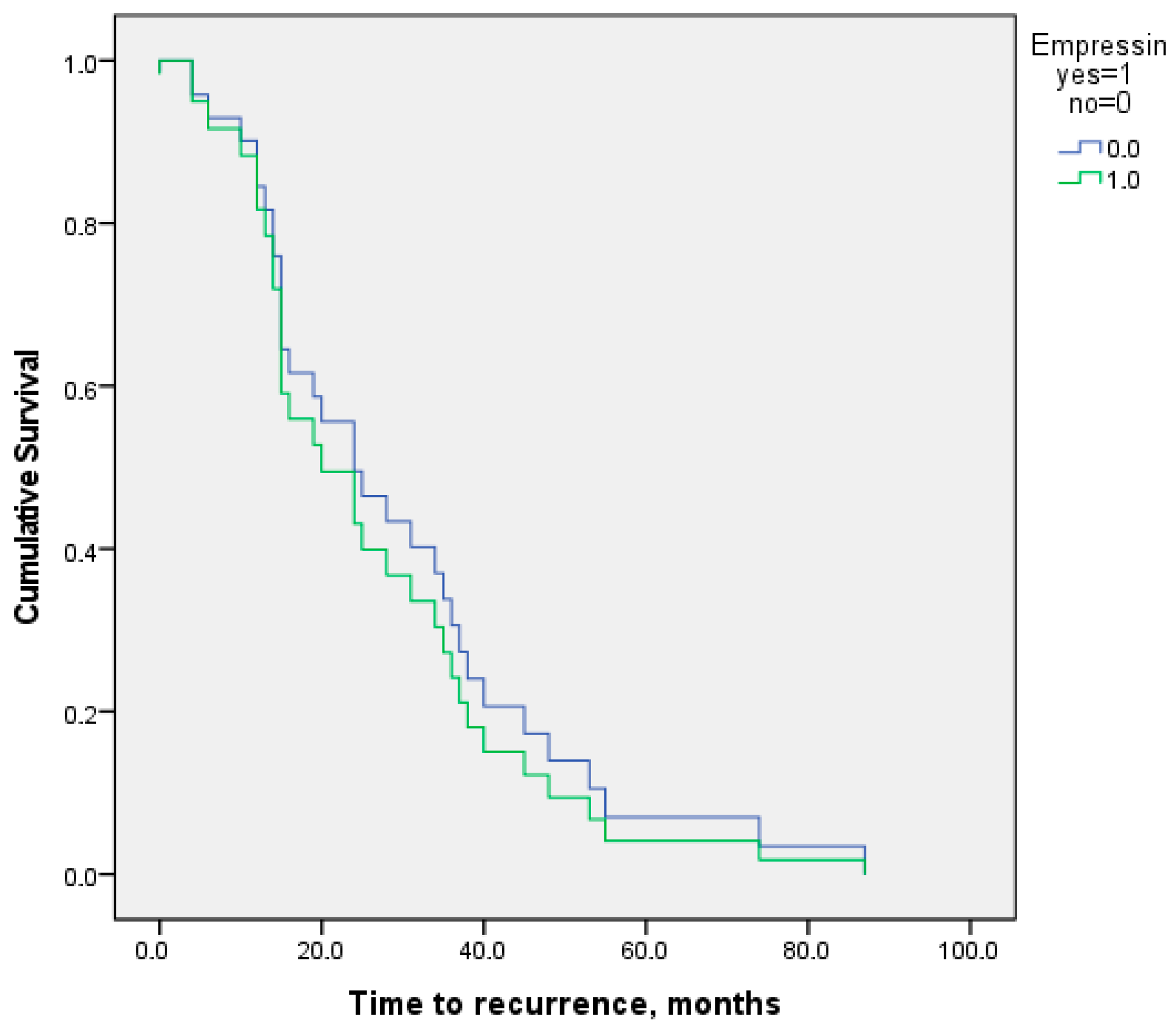

4.1. Impact of Empressin on Recurrence Rate

4.2. Postoperative Hormonal Therapy and Its Synergistic Effect with Empressin

4.3. Cystectomy Versus Laser Ablation

4.4. Expanding the Role of Empressin in Gynecological Surgery

4.5. Cost–Benefit Considerations

4.6. Contraindications and Safety Considerations

4.7. Learning Curve and Operator Requirements

4.8. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DIE | Deep infiltrating endometriosis |

| EIT | Empressin Injection Technique |

| OMA | Endometrioma |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Pagano, F.; Dedes, I.; Imboden, S.; Mueller, M.D. Connecting the dots: Exploring appendiceal endometriosis in women with diaphragmatic endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 302, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagano, F.; Schwander, A.; Vaineau, C.; Knabben, L.; Nirgianakis, K.; Imboden, S.; Mueller, M.D. True Prevalence of Diaphragmatic Endometriosis and Its Association with Severe Endometriosis: A Call for Awareness and Investigation. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzii, L.; Di Tucci, C.; Achilli, C.; Di Donato, V.; Musella, A.; Palaia, I.; Panici, P.B. Continuous versus cyclic oral contraceptives after laparoscopic excision of ovarian endometriomas: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nezhat, F.R.; Cathcart, A.M.; Nezhat, C.H.; Nezhat, C.R. Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications of Ovarian Endometriomas. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 143, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Chapron, C.; De Giorgi, O.; Consonni, D.; Frontino, G.; Crosignani, P.G. Coagulation or excision of ovarian endometriomas? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 188, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J.A. Metastatic or Embolic Endometriosis, due to the Menstrual Dissemination of Endometrial Tissue into the Venous Circulation. Am. J. Pathol. 1927, 3, 93–110.143. [Google Scholar]

- Czernobilsky, B.; Morris, W.J. A histologic study of ovarian endometriosis with emphasis on hyperplastic and atypical changes. Obstet. Gynecol. 1979, 53, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nisolle-Pochet, M.; Casanas-Roux, F.; Donnez, J. Histologic study of ovarian endometriosis after hormonal therapy. Fertil. Steril. 1988, 49, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.M.; Bokor, A.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.; Jansen, F.; Kiesel, L.; King, K.; Kvaskoff, M.; Nap, A.; Petersen, K.; et al. ESHRE guideline: Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Open 2022, 2022, hoac009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, P.S.; Donders, F.; Kobylianskii, A.; Maheux-Lacroix, S.; Matelski, J.; Walsh, C.; Murji, A. The Effect of Hormonal Treatment on Ovarian Endometriomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2024, 31, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alec, M.; Martino, A.; Dallenbach, P.; Wenger, J.M.; Pluchino, N. Combining Sclerotherapy with CO(2) Laser Ablation for the Laparoscopic Management of Large Endometrioma: Advantages and Pitfalls. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, R.; Hickey, M.; Maouris, P.; Buckett, W.; Garry, R. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata: A Cochrane Review. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 3000–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beretta, P.; Franchi, M.; Ghezzi, F.; Busacca, M.; Zupi, E.; Bolis, P. Randomized clinical trial of two laparoscopic treatments of endometriomas: Cystectomy versus drainage and coagulation. Fertil. Steril. 1998, 70, 1176–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Ye, M.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Hou, Q. The effects of vasopressin injection technique on ovarian reserve in laparoscopic cystectomy of bilateral ovarian endometrioma: A retrospective cohort study. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 2343–2349. [Google Scholar]

- Raffi, F.; Metwally, M.; Amer, S. The impact of excision of ovarian endometrioma on ovarian reserve: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 3146–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidis, A.; Grigoriadis, G.; Kalaitzopoulos, D.R.; Angioni, S.; Kalkan, U.; Crestani, A.; Merlot, B.; Roman, H. Surgical Management of Ovarian Endometrioma: Impact on Ovarian Reserve Parameters and Reproductive Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiong-Zhen, R.; Ge, Y.; Deng, Y.; Qian, Z.H.; Zhu, W.P. Effect of vasopressin injection technique in laparoscopic excision of bilateral ovarian endometriomas on ovarian reserve: Prospective randomized study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2014, 21, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukbas, M.; Kurek Eken, M.; Ilhan, G.; Senol, T.; Herkiloglu, D.; Kapudere, B. Which factors are associated with the recurrence of endometrioma after cystectomy? J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 38, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Somigliana, E.; Vigano, P.; De Matteis, S.; Barbara, G.; Fedele, L. Post-operative endometriosis recurrence: A plea for prevention based on pathogenetic, epidemiological and clinical evidence. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2010, 21, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koga, K.; Takemura, Y.; Osuga, Y.; Yoshino, O.; Hirota, Y.; Hirata, T.; Morimoto, C.; Harada, M.; Yano, T.; Taketani, Y. Recurrence of ovarian endometrioma after laparoscopic excision. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 2171–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanayingcharoenchai, R.; Rattanasiri, S.; Charakorn, C.; Attia, J.; Thakkinstian, A. Postoperative hormonal treatment for prevention of endometrioma recurrence after ovarian cystectomy: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BJOG 2021, 128, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, R.; McDonnell, R.; Stewart, F.; Hart, R.J.; Hickey, M.; Farquhar, C. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometrioma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 11, CD004992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busacca, M.; Marana, R.; Caruana, P.; Candiani, M.; Muzii, L.; Calia, C.; Bianchi, S. Recurrence of ovarian endometrioma after laparoscopic excision. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 180 Pt 1, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, I.; Takeuchi, H.; Kitade, M.; Shimanuki, H.; Kumakiri, J.; Kinoshita, K. Recurrence rate of endometriomas following a laparoscopic cystectomy. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2006, 85, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdag, G. Recurrence of endometriosis: Risk factors, mechanisms and biomarkers. Womens Health 2015, 11, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Mao, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wei, X.; Liu, P. Can postoperative GnRH agonist treatment prevent endometriosis recurrence? A meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 294, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.C.; Hsu, T.F.; Jiang, L.Y.; Chan, I.S.; Shih, Y.C.; Chang, Y.H.; Wang, P.H.; Chen, Y.J. Maintenance Therapy for Preventing Endometrioma Recurrence after Endometriosis Resection Surgery—A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2022, 29, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafarnejad, M.; Akrami, M.; Davari-Tanha, F.; Adabi, K.; Nekuie, S. Vasopressin Effect on Operation Time and Frequency of Electrocauterization during Laparoscopic Stripping of Ovarian Endometriomas: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2014, 15, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Saeki, A.; Matsumoto, T.; Ikuma, K.; Tanase, Y.; Inaba, F.; Oku, H.; Kuno, A. The vasopressin injection technique for laparoscopic excision of ovarian endometrioma: A technique to reduce the use of coagulation. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2010, 17, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busacca, M.; Vignali, M. Endometrioma excision and ovarian reserve: A dangerous relation. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2009, 16, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veth, V.B.; Keukens, A.; Reijs, A.; Bongers, M.Y.; Mijatovic, V.; Coppus, S.; Maas, J.W.M. Recurrence after surgery for endometrioma: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Fertil. Steril. 2024, 122, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seracchioli, R.; Mabrouk, M.; Manuzzi, L.; Vicenzi, C.; Frasca, C.; Elmakky, A.; Venturoli, S. Post-operative use of oral contraceptive pills for prevention of anatomical relapse or symptom-recurrence after conservative surgery for endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 2729–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirkel, C.; Gobel, H.; Gobel, C.; Alkatout, I.; Khalil, A.; Bruggemann, N.; Rody, A.; Cirkel, A. Endometrioma patients are under-treated with endocrine endometriosis therapy. Hum. Reprod. 2025, 40, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, H.; Frederick, J.; Hardie, M.; Simeon, D. A randomized comparison of vasopressin and tourniquet as hemostatic agents during myomectomy. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 87, 1014–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, J.W.; Hwang, D.W.; Lee, S.; Yim, G.W.; Song, G.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, H.S. Effect and Safety of Diluted Vasopressin Injection for Bleeding Control During Robot-assisted Laparoscopic Myomectomy in Reproductive Women with Uterine Fibroids: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial (VALENTINE Trial). In Vivo 2024, 38, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobo, R.; Netsu, S.; Koyasu, Y.; Tsutsumi, O. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest caused by intramyometrial injection of vasopressin during a laparoscopically assisted myomectomy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 113, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimanuki, H.; Takeuchi, H.; Kitade, M.; Kikuchi, I.; Kumakiri, J.; Kinoshita, K. The effect of vasopressin on local and general circulation during laparoscopic surgery. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2006, 13, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baradwan, S.; Alshahrani, M.S.; Al Sghan, R.; Sabban, H.; Khadawardi, K.; Alzawawi, N.; Abduljabbar, H.H.; Abdelhakim, A.M.; Al Amodi, A.A.; Elgamel, A.F. Effect of vasopressin injection technique on ovarian reserve during laparoscopic cystectomy of ovarian endometriomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 76, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | EIT Group | Control Group | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | (n = 110) | (n = 153) | ||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 34 ± 5.8 | 35 ± 6.2 | −2.40–0.57 | 0.2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD) | 24 ± 4.9 | 25 ± 5.0 | −1.54–0.89 | 0.6 |

| Previous surgery for endometriosis, n (%) | 32 (29.1%) | 50 (32.7%) | −0.15–0.08 | 0.5 |

| Previous cesarean section, n (%) | 10 (9.1%) | 10 (6.5%) | −0.04–0.09 | 0.4 |

| Preoperative hormonal therapy, n (%) | 76 (69.1%) | 96 (62.7%) | −0.05–0.18 | 0.3 |

| Dysmenorrhea, n (%) | 101 (91.8%) | 129 (84.3%) | −0.002–0.152 | 0.1 |

| Hypermenorrhea, n (%) | 21 (19.1%) | 25 (16.3%) | −0.07–0.12 | 0.6 |

| Dyspareunia, n (%) | 57 (51.8%) | 64 (41.8%) | −0.02–0.22 | 0.1 |

| Dyschezia, n (%) | 42 (38.2%) | 55 (35.9%) | −0.10–0.14 | 0.7 |

| Dysuria, n (%) | 14 (12.8%) | 11 (7.2%) | −0.02–0.13 | 0.1 |

| Chronic pelvic pain, n (%) | 34 (30.9%) | 60 (39.2%) | −0.2–0.03 | 0.2 |

| Previous history of infertility, n (%) | 41 (37.3%) | 43 (28.1%) | −0.02–0.21 | 0.1 |

| r-ASRM score | 0.2 | |||

| r-ASRM I n (%) | 1 (0.9%) | 4 (2.6%) | ||

| r-ASRM II n (%) | 14 (12.7%) | 16 (10.5%) | ||

| r-ASRM III n (%) | 30 (27.3%) | 59 (38.6%) | ||

| r-ASRM IV n (%) | 65 (59.1%) | 74 (48.4%) | ||

| Postoperative hormonal therapy, n (%) | 63 (57.3%) | 87 (56.9%) | −0.12–0.13 | 0.9 |

| Variable | OR (Odds Ratio) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of Empressin (yes vs. no) | 0.2 | 0.07–0.52 | 0.001 |

| Age (per year) | 0.95 | 0.88–1.02 | 0.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.95 | 0.95–1.09 | 0.6 |

| O left | 0.7 | ||

| –Enzian O 1/0 | 1 | 0.31–3.3 | 0.9 |

| –Enzian O 2/0 | 1.7 | 0.57–5 | 0.3 |

| –Enzian O 3/0 | 1.4 | 0.32–5.82 | 0.7 |

| O right | 0.7 | ||

| –Enzian O 0/1 | 0.7 | 0.21–2.5 | 0.6 |

| –Enzian O 0/2 | 1.1 | 0.42–3.12 | 0.8 |

| –Enzian O 0/3 | 1.7 | 0.44–6.32 | 0.5 |

| Preoperative hormonal treatment | 0.9 | 0.41–2.05 | 0.8 |

| Postoperative hormonal treatment | 2.4 | 0.96–6 | 0.06 |

| Time (Months) | EIT, n (%) | Control, n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 110 | 153 | - | |

| 6 | 0 (0) | 6 (3.9) | 0.06 |

| 12 | 1 (0.9) | 8 (5.2) | 0.2 |

| 24 | 4 (3.6) | 18 (11.8) | 0.7 |

| 36 | 5 (4.5) | 23 (15) | 0.8 |

| 48 | 6 (5.5) | 27 (17.6) | 0.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagano, F.; Dedes, I.; Vaineau, C.; Siegenthaler, F.; Imboden, S.; Mueller, M.D. Is the EMpressin Injection in ENDOmetrioma eXcision Surgery Useful? The EMENDOX Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7716. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217716

Pagano F, Dedes I, Vaineau C, Siegenthaler F, Imboden S, Mueller MD. Is the EMpressin Injection in ENDOmetrioma eXcision Surgery Useful? The EMENDOX Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7716. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217716

Chicago/Turabian StylePagano, Flavia, Ioannis Dedes, Cloé Vaineau, Franziska Siegenthaler, Sara Imboden, and Michael David Mueller. 2025. "Is the EMpressin Injection in ENDOmetrioma eXcision Surgery Useful? The EMENDOX Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7716. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217716

APA StylePagano, F., Dedes, I., Vaineau, C., Siegenthaler, F., Imboden, S., & Mueller, M. D. (2025). Is the EMpressin Injection in ENDOmetrioma eXcision Surgery Useful? The EMENDOX Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7716. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217716