Incidence and Outcomes of High-Output Heart Failure in Patients with Arteriovenous Fistula: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- CKD/ESRD with AVF with a documented history of heart failure based on the ICD diagnosis.

- Patients who had RHC performed after AV fistula creation.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Age > 85 years or <18 years.

- Patients with other causes of HOHF, like liver cirrhosis/thyrotoxicosis at the time of RHC, anemia with hemoglobin < 8 g/dL at the time of RHC, or obesity with BMI > 35 kg/m2.

- Patients who had an iatrogenic fistula as a complication of a medical procedure (like Cardiac Cath) involving vascular access.

- Patients with a spontaneous/congenital fistula.

2.2.3. High-Output Heart Failure

2.2.4. Outcome

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Bivariate Analysis

- Time interval from arteriovenous fistula (AVF) creation to RHC, measured in months.

- Presence of coronary artery disease.

- Presence of atrial fibrillation.

- Personal history of hypertension.

- History of diabetes mellitus.

- Use of beta-blockers.

- Use of ACE-Inhibitor (ACE-I) or Angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

- Use of diuretics.

- Hemoglobin levels were recorded based on the value reported closest to the time of right heart catheterization (RHC).

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels were obtained from the measurement closest to the timing of RHC.

- Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was assessed using echocardiographic data available nearest to the time of RHC.

- Follow-up interval after RHC.

- Mortality data.

2.3.2. Regression Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Mortality Comparison

3.2. Follow-Up Comparison (in Months)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AVF | Arteriovenous fistula |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| HOHF | High-output heart failure |

| LVH | Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| RHC | Right heart catheterization |

| ACE-I | ACE-Inhibitor |

| ARB | Angiotensin receptor blocker |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| PH | Pulmonary Hypertension |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

Appendix A

| Item No. | Recommendation | Location in Manuscript |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Indicate the study design with a commonly used term in the title or abstract | Title (‘Retrospective cohort study’), Abstract |

| 2. | Provide an informative and balanced summary of what was performed and found | Abstract |

| 3. | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation | Introduction, Paragraphs 1–3 |

| 4. | State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses | Introduction, final paragraph |

| 5. | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | ‘Study Design’ subsection |

| 6. | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment and data collection | Study Design’ and ‘Selection Criteria’ subsections (2011–2023, KUMC) |

| 7. | Clearly define all eligibility criteria, and sources/methods of selection of participants | ‘Selection Criteria’ subsection |

| 8. | For matched studies, give matching criteria and number of exposed/unexposed | Not applicable |

| 9. | Clearly define all variables, including outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers | ‘High-output heart failure’ and ‘Outcome’ subsections |

| 10. | Give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement) | ‘Study Design’ and ‘Statistical Analysis’ subsections |

| 11. | Describe efforts to address potential sources of bias | Discussion—Limitations paragraph |

| 12. | Explain how the study size was arrived at | Methods (‘34 patients fulfilled all criteria’) |

| 13. | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses | ‘Statistical Analysis’ subsection |

| 14. | Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding | ‘Statistical Analysis’ subsection (bootstrap/quantile regression, bivariate analysis) |

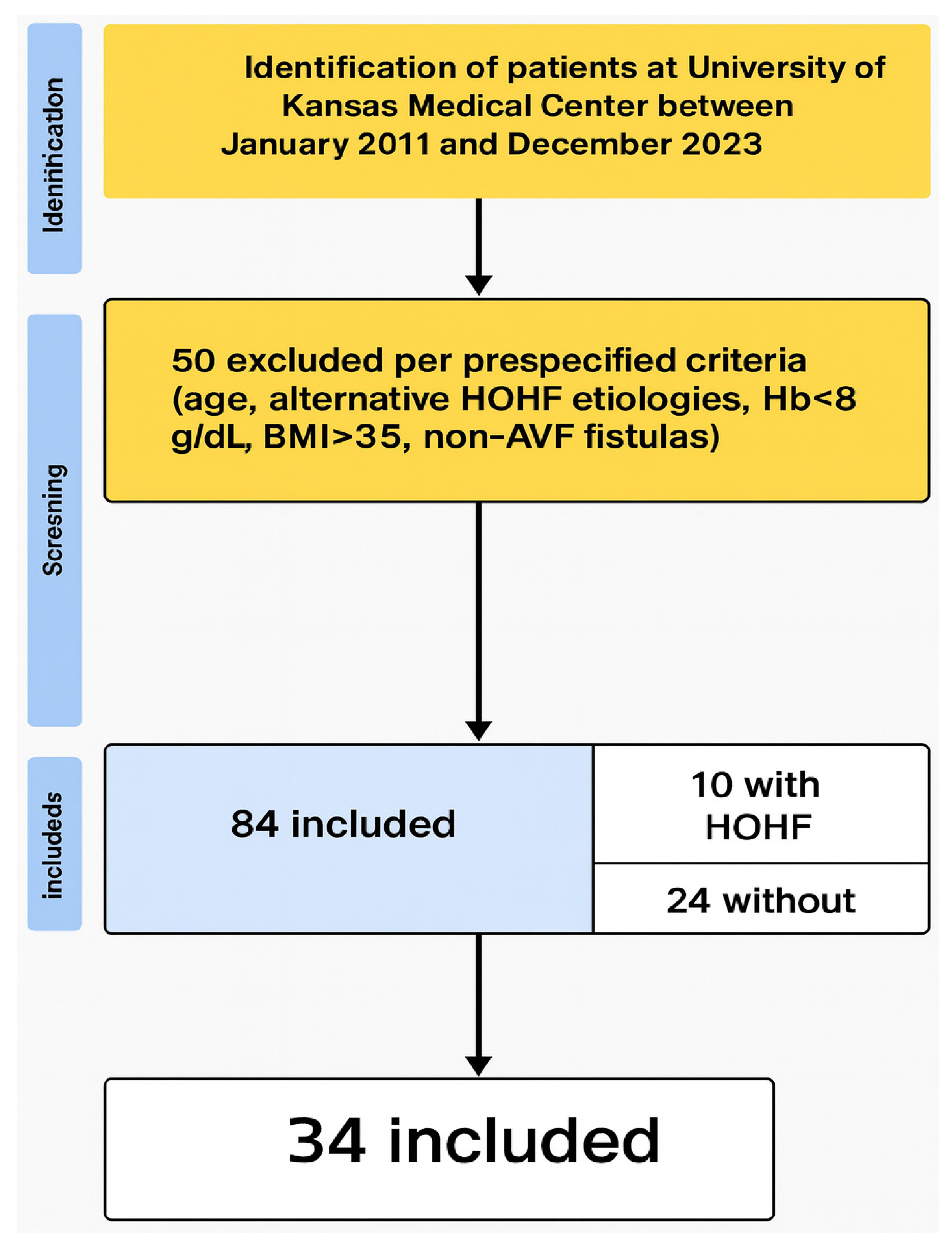

| 15. | Report numbers of individuals at each stage (e.g., eligible, included, analyzed); give reasons for exclusions | Results (first paragraph); Figure 1 (flow diagram) |

| 16. | Give characteristics of study participants and information on exposures/potential confounders | Table 1 |

| 17. | Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures over time | Results first paragraph, Table 6 |

| 18. | Provide unadjusted and confounder-adjusted estimates with precision (e.g., 95% CI) | Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 |

| 19. | Report other analyses performed, such as subgroup and sensitivity analyses | Table 5 and Table 6, Results narrative |

| 20. | Summarize key results with reference to study objectives | Discussion—first paragraph |

| 21. | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision | Discussion—‘Limitations’ subsection |

| 22. | Give a cautious overall interpretation considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, and results from similar studies | Discussion—final paragraphs |

| 23. | Give the source of funding and the role of funders, if any | No external funding (implied in Methods/End section) |

| 24. | Ethical approval and informed consent | ‘Study Design’ (IRB approval #STUDY00148490) |

References

- Hicks, C.W.; Wang, P.; Kernodle, A.; Lum, Y.W.; Black, J.H., 3rd; Makary, M.A. Assessment of Use of Arteriovenous Graft vs Arteriovenous Fistula for First-time Permanent Hemodialysis Access. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.; Attallah, N.; Younes, H.; Park, W.S.; Bader, F. Clinical and Haemodynamic Effects of Arteriovenous Shunts in Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Card. Fail. Rev. 2022, 8, e05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praehauser, C.; Breidthardt, T.; Moser-Bucher, C.N.; Wolff, T.; Baechler, K.; Eugster, T.; Dickenmann, M.; Gurke, L.; Mayr, M. The outcome of the primary vascular access and its translation into prevalent access use rates in chronic haemodialysis patients. Clin. Kidney J. 2012, 5, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasir, M.B.; Man, R.K.; Gogikar, A.; Nanda, A.; Niharika Janga, L.S.; Sambe, H.G.; Mohamed, L. A Systematic Review Exploring the Impact of Arteriovenous Fistula Ligature on High-Output Heart Failure in Renal Transplant Recipients. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 100, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, E.D.; Brailovsky, Y.; Oliveros, E.; Bhardwaj, A.; Rajapreyar, I.N. High-Output Heart Failure, Pulmonary Hypertension and Right Ventricular Failure in Patients with Arteriovenous Fistulas: A Call to Action. J. Card. Fail. 2023, 29, 979–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.N.; Stokes, M.B.; Rajwani, A.; Ullah, S.; Williams, K.; King, D.; Macaulay, E.; Russell, C.H.; Olakkengil, S.; Carroll, R.P.; et al. Effects of Arteriovenous Fistula Ligation on Cardiac Structure and Function in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Circulation 2019, 139, 2809–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, M.A.; El Kilany, W.M.; Keddis, V.W.; El Said, T.W. Effect of high flow arteriovenous fistula on cardiac function in hemodialysis patients. Egypt. Heart J. 2018, 70, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movilli, E.; Viola, B.F.; Brunori, G.; Gaggia, P.; Camerini, C.; Zubani, R.; Berlinghieri, N.; Cancarini, G. Long-term effects of arteriovenous fistula closure on echocardiographic functional and structural findings in hemodialysis patients: A prospective study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 55, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.R.; Giblin, L.; Brown, A.; Little, D.; Donohoe, J. Reversal of pulmonary hypertension after ligation of a brachiocephalic arteriovenous fistula. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2002, 40, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio-Pertuz, G.; Nugent, K.; Argueta-Sosa, E. Right heart catheterization in clinical practice: A review of basic physiology and important issues relevant to interpretation. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 13, 122–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bews, H.; Jia, S.; Liu, Y.; Sklar, J.; Ducas, J.; Kirkpatrick, I.; Tam, J.W.; Shah, A.H. High output cardiac state: Evaluating the incidence, plausible etiologies and outcomes. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, Y.N.V.; Melenovsky, V.; Redfield, M.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Borlaug, B.A. High-Output Heart Failure: A 15-Year Experience. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, L.; Sperandeo, L.; Forzano, I.; Castiello, D.S.; Florimonte, D.; Paolillo, R.; Santoro, C.; Mancusi, C.; Di Serafino, L.; Esposito, G.; et al. Contemporary Evidence and Practice on Right Heart Catheterization in Patients with Acute or Chronic Heart Failure. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozos, I. Mechanisms linking red blood cell disorders and cardiovascular diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 682054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A. Anemia and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease populations: A review of the current state of knowledge. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2002, 61, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.M.; Chen, S.C.; Huang, J.C.; Su, H.M.; Chen, H.C. Anemia and left ventricular hypertrophy with renal function decline and cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 347, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majmundar, M.; Doshi, R.; Zala, H.; Shah, P.; Adalja, D.; Shariff, M.; Kumar, A. Prognostic role of anemia in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian Heart J. 2021, 73, 521–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köseoğlu, F.D.; Özlek, B. Anemia and Iron Deficiency Predict All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: 6-Year Follow-up Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenberg, N.C.; Argula, R.G.; Klings, E.S.; Wilson, K.C.; Farber, H.W. Prevalence and Mortality of Pulmonary Hypertension in ESRD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lung 2020, 198, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, C.; Lomonte, C.; Vernaglione, L.; Casucci, F.; Antonelli, M.; Losurdo, N. The relationship between the flow of arteriovenous fistula and cardiac output in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabria, M.S.; Persaud, P.N.; Kamel, M.H.; Tonelli, A.R.; Siuba, M.T. Hemodynamic Impact of Hemodialysis Arteriovenous Access Compression During Right-Heart Catheterization: A Retrospective Cohort. J. Card. Fail. 2023, 29, 1466–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dundon, B.K.; Torpey, K.; Nelson, A.J.; Wong, D.T.; Duncan, R.F.; Meredith, I.T.; Faull, R.J.; Worthley, S.G.; Worthley, M.I. The deleterious effects of arteriovenous fistula-creation on the cardiovascular system: A longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Int. J. Nephrol. Renovasc. Dis. 2014, 7, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccali, C.; Benedetto, F.A.; Mallamaci, F.; Tripepi, G.; Giacone, G.; Stancanelli, B.; Cataliotti, A.; Malatino, L.S. Left ventricular mass monitoring in the follow-up of dialysis patients: Prognostic value of left ventricular hypertrophy progression. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasse, H.; Singapuri, M.S. High-output heart failure: How to define it, when to treat it, and how to treat it. Semin. Nephrol. 2012, 32, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poleszczuk, J.; Debowska, M.; Dabrowski, W.; Wojcik-Zaluska, A.; Zaluska, W.; Waniewski, J. Patient-specific pulse wave propagation model identifies cardiovascular risk characteristics in hemodialysis patients. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1006417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.T.; Ferro, C.J.; Sassano, A.; Tomson, C.R. The impact of arteriovenous fistula formation on central hemodynamic pressures in chronic renal failure patients: A prospective study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2002, 40, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | High-Output Heart Failure | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 10) | No (n = 24) | ||

| Age (mean (SD)) | 47.8 (13.66) | 54.5 (12.01) | 0.19 |

| Sex = Male (%) | 6 (60.0) | 17 (70.8) | 0.69 |

| Race (%) | 0.21 | ||

| Black | 5 (50.0) | 5 (20.8) | |

| White | 3 (30.0) | 15 (62.5) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (10.0) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Other | 1 (10.0) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Time from fistula creation to RHC in months [mean (SD)] | 67.7 (60.47) | 78.7 (73.30) | 0.88 |

| CAD (%) | 5 (50.0) | 15 (62.5) | 0.70 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 3 (30.0) | 8 (33.3) | 1 |

| HTN (%) | 10 (100.0) | 23 (95.8) | 1 |

| DM (%) | 5 (50.0) | 15 (62.5) | 0.70 |

| BB (%) | 8 (80.0) | 13 (54.2) | 0.25 |

| ACEI/ARB (%) | 4 (40.0) | 6 (25.0) | 0.43 |

| Diuretics (%) | 6 (60.0) | 13 (54.2) | 1 |

| Hb [mean (SD)] g/dL | 10.16 (1.22) | 11.52 (1.70) | 0.02 |

| TSH [mean (SD)] uIU/mL | 1.69 (1.09) | 3.41 (4.88) | 0.18 |

| LVEF in percentage [mean (SD)] | 59.80 (7.86) | 48.17 (19.10) | 0.30 |

| Variables | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI for Risk Ratio | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Bivariant Analysis | ||||

| Sex (Male) | 0.72 | 0.25 | 2.03 | 0.69 |

| Race | 0.21 | |||

| Black | Reference | |||

| White | 0.33 | 0.08 | 1.07 | |

| Hispanic | 0.66 | 0.04 | 2.50 | |

| Other | 0.66 | 0.04 | 2.50 | |

| CAD | 0.70 | 0.25 | 1.97 | 0.70 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.90 | 0.28 | 2.82 | 1 |

| DM | 0.70 | 0.25 | 1.97 | 0.70 |

| BB | 2.48 | 0.62 | 9.91 | 0.25 |

| ACEI or ARB | 1.60 | 0.57 | 4.47 | 0.43 |

| Diuretics | 1.18 | 0.41 | 3.45 | 1 |

| Multivariant Analysis: | ||||

| Age (in years) | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.02 |

| Sex (male) | 0.94 | 0.61 | 1.39 | 0.43 |

| CAD | 1.30 | 0.81 | 1.94 | 0.16 |

| Afib | 1.13 | 0.78 | 1.56 | 0.42 |

| DM | 1.06 | 0.73 | 1.42 | 0.42 |

| ACEI or ARB Use | 1.10 | 0.71 | 1.66 | 0.38 |

| Beta-Blocker Use | 1.00 | 0.64 | 1.59 | 0.46 |

| Diuretics Use | 1.22 | 0.79 | 1.93 | 0.25 |

| Time from Fistula Creation to RHC (in months) | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.16 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.98 | <0.01 |

| LVEF (%) | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | <0.01 |

| Variables | Means Difference | 95% CI for Means Difference | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Age (mean (SD)) | 6.74 | −3.84 | 17.32 | 0.19 |

| Hemoglobin (mean (SD)) | 1.36 | 0.28 | 2.43 | 0.02 |

| Variables | Difference in Location | 95% CI for Difference in Location | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Time from fistula creation to RHC in months (mean (SD)) | 4.17 | −34.00 | 59.00 | 0.88 |

| TSH (mean (SD)) | 0.61 | −0.18 | 1.60 | 0.18 |

| LVEF in percentage (mean (SD)) | 8.00 | −4.00 | 25.00 | 0.30 |

| Variables | HOHF = Yes (n = 10) | HOHF = No (n = 24) | p-Value | Statistical Test Used | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | Median | |||

| LVEF (%) | 59.8 | 60.0 | 48.2 | 55.0 | 0.30 | Wilcoxon signed-rank test |

| LVEDD (cm) | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 0.85 | t-test |

| IVS (cm) | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.59 | t-test |

| PWT (cm) | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.94 | t-test |

| RHC Data Elements | HOHF | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 10) | No (n = 24) | ||

| RA (mean (SD)) mmHg | 11.40 (5.82) | 10.21 (4.93) | 0.55 |

| PA Mean (mean (SD)), mmHg | 33.90 (7.37) | 27.62 (9.11) | 0.06 |

| PCWP (mean (SD)) | 17.40 (6.96) | 16.50 (7.48) | 0.75 |

| CO Fick (mean (SD)) L/min | 7.93 (1.21) | 5.96 (1.82) | <0.01 |

| CI Fick (mean (SD)) L/min/m2 | 4.54 (0.89) | 2.91 (0.79) | <0.01 |

| CO Thermo (mean (SD)) | 7.30 (1.16) | 5.36 (2.10) | 0.01 |

| CI Thermo (mean (SD)) | 4.14 (0.73) | 2.61 (0.93) | <0.01 |

| PVR (mean (SD)) | 2.15 (0.81) | 2.07 (1.05) | 0.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tripathi, A.; Hanten, B.; Shafiq, M.; Tiwari, A.; Gautam, A.; Bhyan, P.; Dalia, T.; Gupta, B. Incidence and Outcomes of High-Output Heart Failure in Patients with Arteriovenous Fistula: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217689

Tripathi A, Hanten B, Shafiq M, Tiwari A, Gautam A, Bhyan P, Dalia T, Gupta B. Incidence and Outcomes of High-Output Heart Failure in Patients with Arteriovenous Fistula: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217689

Chicago/Turabian StyleTripathi, Alok, Brandon Hanten, Muhammad Shafiq, Ankita Tiwari, Archana Gautam, Pratik Bhyan, Tarun Dalia, and Bhanu Gupta. 2025. "Incidence and Outcomes of High-Output Heart Failure in Patients with Arteriovenous Fistula: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217689

APA StyleTripathi, A., Hanten, B., Shafiq, M., Tiwari, A., Gautam, A., Bhyan, P., Dalia, T., & Gupta, B. (2025). Incidence and Outcomes of High-Output Heart Failure in Patients with Arteriovenous Fistula: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217689