Comparative Renal Safety of Tirzepatide and Semaglutide: An FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)—Disproportionality Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

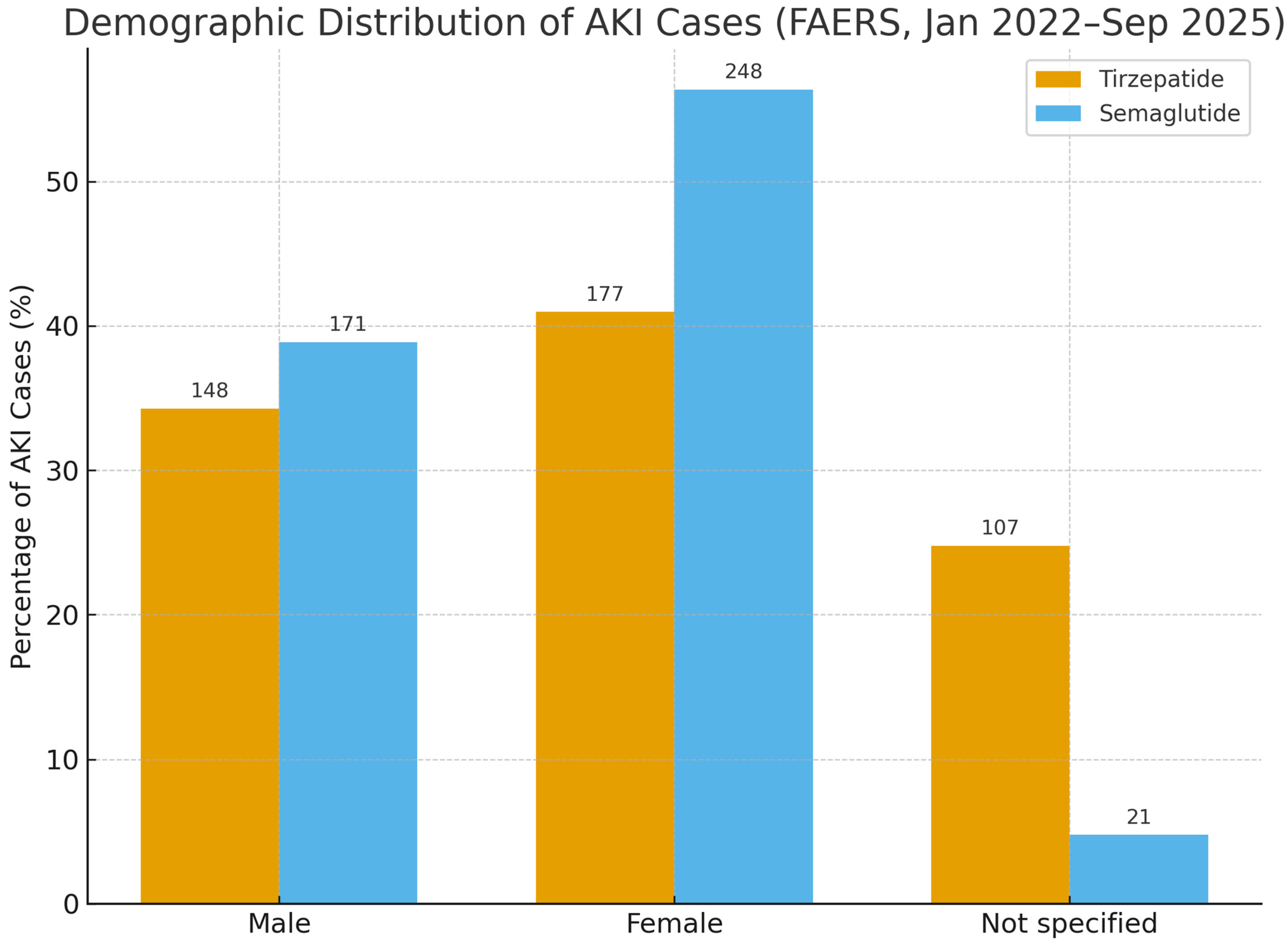

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanistic Considerations

4.2. Perspectives for Clinical Practice

4.3. Reporting Dynamics and Market Exposure

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, J.; Liu, J.-J.; Liu, S.; Liu, A.; Zheng, H.; Chan, C.; Shao, Y.M.; Gurung, R.L.; Ang, K.; Lim, S.C. Acute kidney injury predicts the risk of adverse cardio renal events and all cause death in southeast Asian people with type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, I.; Giorgino, F. Renal effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists and tirzepatide in individuals with type 2 diabetes: Seeds of a promising future. Endocrine 2024, 84, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaman, A.M.; Bain, S.C.; Bakris, G.L.; Buse, J.B.; Idorn, T.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Mann, J.F.E.; Nauck, M.A.; Rasmussen, S.; Rossing, P.; et al. Effect of the Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Semaglutide and Liraglutide on Kidney Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Pooled Analysis of SUSTAIN 6 and LEADER. Circulation 2022, 145, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, P.; Green, S.C.; Tunnicliffe, D.J.; Pellegrino, G.; Toyama, T.; Strippoli, G.F. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists for people with chronic kidney disease and diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 2, Cd015849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, K.R.; Bosch-Traberg, H.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; Hadjadj, S.; Lawson, J.; Mosenzon, O.; Rasmussen, S.; Bain, S.C. Post hoc analysis of SUSTAIN 6 and PIONEER 6 trials suggests that people with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk treated with semaglutide experience more stable kidney function compared with placebo. Kidney Int. 2023, 103, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishkin, A.; Rozenberg, A.; Schechter, M.; Sehtman-Shachar, D.R.; Aharon-Hananel, G.; Leibowitz, G.; Yanuv, I.; Mosenzon, O. Kidney Outcomes with Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists versus Other Glucose-Lowering Agents in People with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Real-World Data. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2025, 41, e70066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, I.H.; Khunti, K.; Sadusky, T.; Tuttle, K.R.; Neumiller, J.J.; Rhee, C.M.; Rosas, S.E.; Rossing, P.; Bakris, G. Diabetes management in chronic kidney disease: A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2022, 102, 974–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, B.; Pelletier, J.; Koyfman, A.; Bridwell, R.E. GLP-1 agonists: A review for emergency clinicians. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 78, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaakeh, Y.; Kanjee, S.; Boone, K.; Sutton, J. Liraglutide-induced acute kidney injury. Pharmacotherapy 2012, 32, e7–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.M.Y.; Sattar, N.; Pop-Busui, R.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Mann, J.F.E.; Marx, N.; Mulvagh, S.L.; Poulter, N.R.; et al. Cardiovascular and Kidney Outcomes and Mortality with Long-Acting Injectable and Oral Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Trials. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, 846–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leehey, D.J.; Rahman, M.A.; Borys, E.; Picken, M.M.; Clise, C.E. Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Semaglutide. Kidney Med. 2021, 3, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkum, M.; Lau, W.; Blanco, P.; Farah, M. Semaglutide-Associated Acute Interstitial Nephritis: A Case Report. Kidney Med. 2022, 4, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Sun, C. Can glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists cause acute kidney injury? An analytical study based on post-marketing approval pharmacovigilance data. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1032199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorli, C.; Harashima, S.I.; Tsoukas, G.M.; Unger, J.; Karsbøl, J.D.; Hansen, T.; Bain, S.C. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide monotherapy versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 1): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multinational, multicentre phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroda, V.R.; Erhan, U.; Jelnes, P.; Meier, J.J.; Abildlund, M.T.; Pratley, R.; Vilsbøll, T.; Husain, M. Safety and tolerability of semaglutide across the SUSTAIN and PIONEER phase IIIa clinical trial programmes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2023, 25, 1385–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Sattar, N.; Pavo, I.; Haupt, A.; Duffin, K.L.; Yang, Z.; Wiese, R.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Cherney, D.Z.I. Effects of tirzepatide versus insulin glargine on kidney outcomes in type 2 diabetes in the SURPASS-4 trial: Post-hoc analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apperloo, E.M.; Tuttle, K.R.; Pavo, I.; Haupt, A.; Taylor, R.; Wiese, R.J.; Hemmingway, A.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; Sattar, N.; Heerspink, H.J.L. Tirzepatide Associated with Reduced Albuminuria in Participants with Type 2 Diabetes: Pooled Post Hoc Analysis from the Randomized Active- and Placebo-Controlled SURPASS-1-5 Clinical Trials. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xie, J.; Han, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z. A real-world disproportionality analysis of tirzepatide-related adverse events based on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database. Endocr. J. 2025, 72, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Wade, A.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; Yajnik, C.; Thomas, N.; Egede, L.E.; Campbell, J.A.; Walker, R.J.; Maple-Brown, L.; Graham, S. The role of structural racism and geographical inequity in diabetes outcomes. Lancet 2023, 402, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, T.; Lu, J.; He, W.; Chen, H.; Wen, T.; Jin, J.; He, Q. Trends and analysis of risk factor differences in the global burden of chronic kidney disease due to type 2 diabetes from 1990 to 2021: A population-based study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 1902–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, T.; Khan, A.H.; Sadiq, F.; Sulaiman, S.A.S.; Khan, A.; Ain, Q. Impact of COVID-19 on nephropathy in diabetes mellitus type-II patients: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2024, 25, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, V.; Tuttle, K.R.; Rossing, P.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Mann, J.F.E.; Bakris, G.; Baeres, F.M.M.; Idorn, T.; Bosch-Traberg, H.; Lausvig, N.L.; et al. Effects of Semaglutide on Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantanetti, P.; Ronconi, V.; Sguanci, M.; Palomares, S.M.; Mancin, S.; Tartaglia, F.C.; Cangelosi, G.; Petrelli, F. Oral Semaglutide in Type 2 Diabetes: Clinical-Metabolic Outcomes and Quality of Life in Real-World Practice. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaeda, T.; Tamon, A.; Kadoyama, K.; Okuno, Y. Data mining of the public version of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 10, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.J.; Waller, P.C.; Davis, S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2001, 10, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equator Network. Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency of Health Research. 2025. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Kim, T.H.; Lee, K.; Park, S.; Oh, J.; Park, J.; Jo, H.; Lee, H.; Cho, J.; Wen, X.; Cho, H.; et al. Adverse drug reaction patterns of GLP-1 receptor agonists approved for obesity treatment: Disproportionality analysis from global pharmacovigilance database. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 3490–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feier, C.V.I.; Vonica, R.C.; Faur, A.M.; Streinu, D.R.; Muntean, C. Assessment of Thyroid Carcinogenic Risk and Safety Profile of GLP1-RA Semaglutide (Ozempic) Therapy for Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.F.E.; Hansen, T.; Idorn, T.; Leiter, L.A.; Marso, S.P.; Rossing, P.; Seufert, J.; Tadayon, S.; Vilsbøll, T. Effects of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide on kidney function and safety in patients with type 2 diabetes: A post-hoc analysis of the SUSTAIN 1-7 randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaneethan, S.D.; Bansal, N.; Cavanaugh, K.L.; Chang, A.; Crowley, S.; Delgado, C.; Estrella, M.M.; Ghossein, C.; Ikizler, T.A.; Koncicki, H.; et al. KDOQI US Commentary on the KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2025, 85, 135–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, J.; Fonseca, V.A.; Gross, J.L.; Ratner, R.E.; Ahrén, B.; Chow, F.C.; Yang, F.; Miller, D.; Johnson, S.L.; Stewart, M.W.; et al. Advancing basal insulin replacement in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with insulin glargine plus oral agents: A comparison of adding albiglutide, a weekly GLP-1 receptor agonist, versus thrice-daily prandial insulin lispro. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2317–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterle, T.S.; Ho, M.-F. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists: A New Frontier in Treating Alcohol Use Disorder. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crajoinas, R.O.; Oricchio, F.T.; Pessoa, T.D.; Pacheco, B.P.; Lessa, L.M.; Malnic, G.; Girardi, A.C. Mechanisms mediating the diuretic and natriuretic actions of the incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2011, 301, F355–F363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hviid, A.V.R.; Sørensen, C.M. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors in the kidney: Impact on renal autoregulation. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2020, 318, F443–F454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Holstein-Rathlou, N.H.; Sosnovtseva, O.; Sørensen, C.M. Renoprotective effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors-is hemodynamics the key point? Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2023, 325, C243–C256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.C.; Huang, F.Z.; Ying, J.; Zhang, T.T.; Huang, H.Y. Genetically proxied glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist is associated with risk of tubulo-interstitial nephritis: A network Mendelian randomization study. Medicine 2025, 104, e44742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, R.; Basheer, F.T.; Poojari, P.G.; Thunga, G.; Chandran, V.P.; Acharya, L.D. Adverse drug reactions of GLP-1 agonists: A systematic review of case reports. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2022, 16, 102427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, M.-H.; Chen, J.-Y.; Wang, H.-Y.; Jiang, Z.-H.; Wu, V.-C. Clinical Outcomes of Tirzepatide or GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2427258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.C.; Cooper, M.E.; Zimmet, P. Changing epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and associated chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raičević, B.; Belančić, A.; Mirkovic, N.; Jankovic, S. Analysis of Reporting Trends of Serious Adverse Events Associated with Anti-Obesity Drugs. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2025, 13, e70080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnell, N.R.; Wilson, J.P. Replication of the Weber effect using postmarketing adverse event reports voluntarily submitted to the United States Food and Drug Administration. Pharmacotherapy 2004, 24, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Drug | AKI (Event) | Non-AKI (No Event) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tirzepatide (Drug of Interest) | a = 432 | b = 92,375 | 92,807 |

| Semaglutide (Comparator) | c = 440 | d = 40,625 | 41,065 |

| Drug | Total AEs | AKI Cases | AKI Rate (%) | ROR (95% CI) | PRR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tirzepatide | 92,807 | 432 | 0.47 | 0.44 (0.38–0.50) | 0.44 |

| Semaglutide | 41,065 | 440 | 1.07 | Reference | Ref |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gandhi, A.; Bhatt, N.; Parhizgar, A. Comparative Renal Safety of Tirzepatide and Semaglutide: An FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)—Disproportionality Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7678. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217678

Gandhi A, Bhatt N, Parhizgar A. Comparative Renal Safety of Tirzepatide and Semaglutide: An FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)—Disproportionality Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7678. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217678

Chicago/Turabian StyleGandhi, Ayush, Nilay Bhatt, and Alireza Parhizgar. 2025. "Comparative Renal Safety of Tirzepatide and Semaglutide: An FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)—Disproportionality Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7678. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217678

APA StyleGandhi, A., Bhatt, N., & Parhizgar, A. (2025). Comparative Renal Safety of Tirzepatide and Semaglutide: An FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)—Disproportionality Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7678. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217678