Spherical Coordinate System for Dyslipoproteinemia Phenotyping and Risk Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Acquisition

2.2. Definition of ASCVD and Metabolic Syndrome

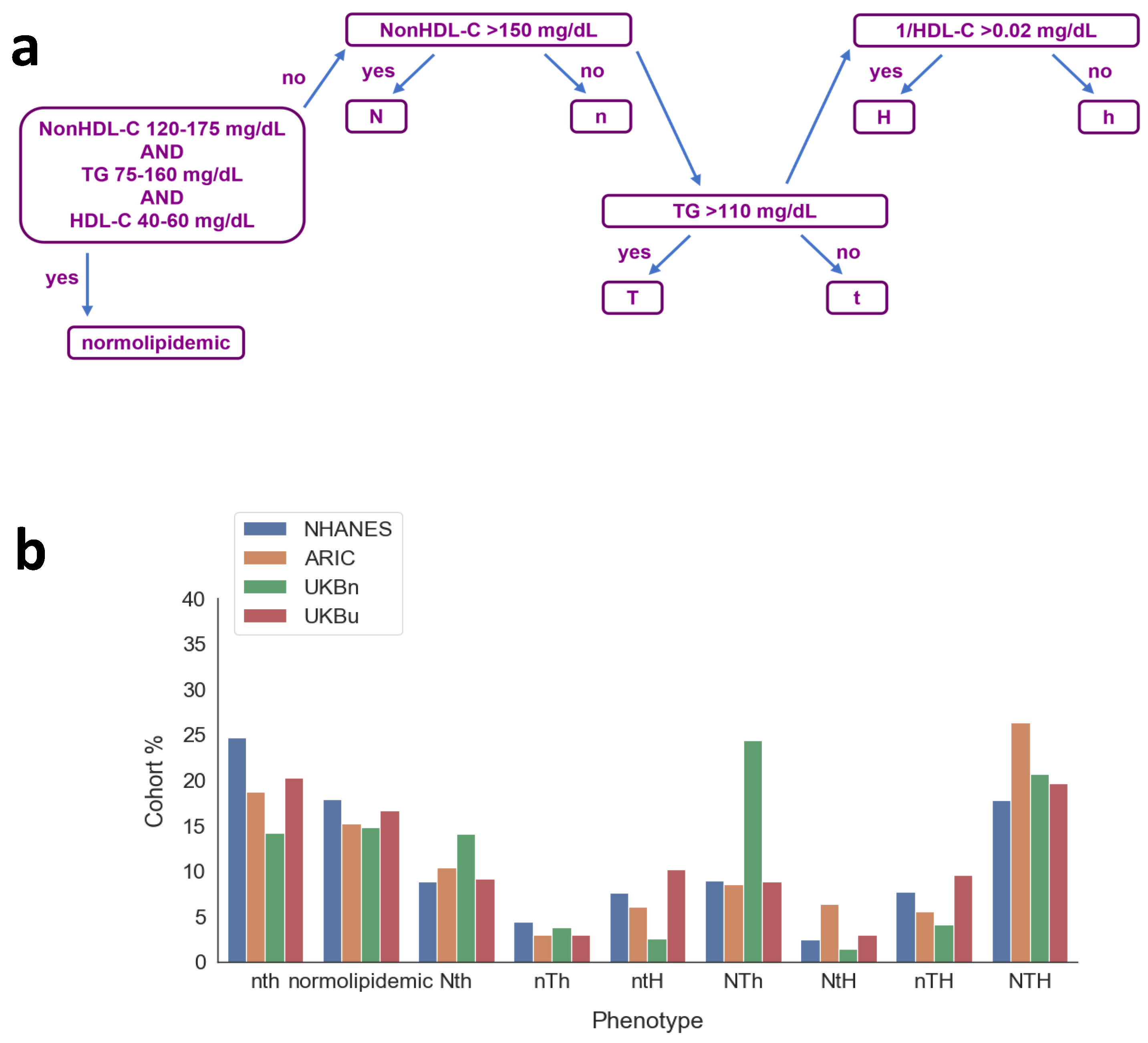

2.3. Phenotype Classification

2.4. Development of Spherical Coordinate Metrics and Model

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Summary Data

3.2. Novel Phenotype System

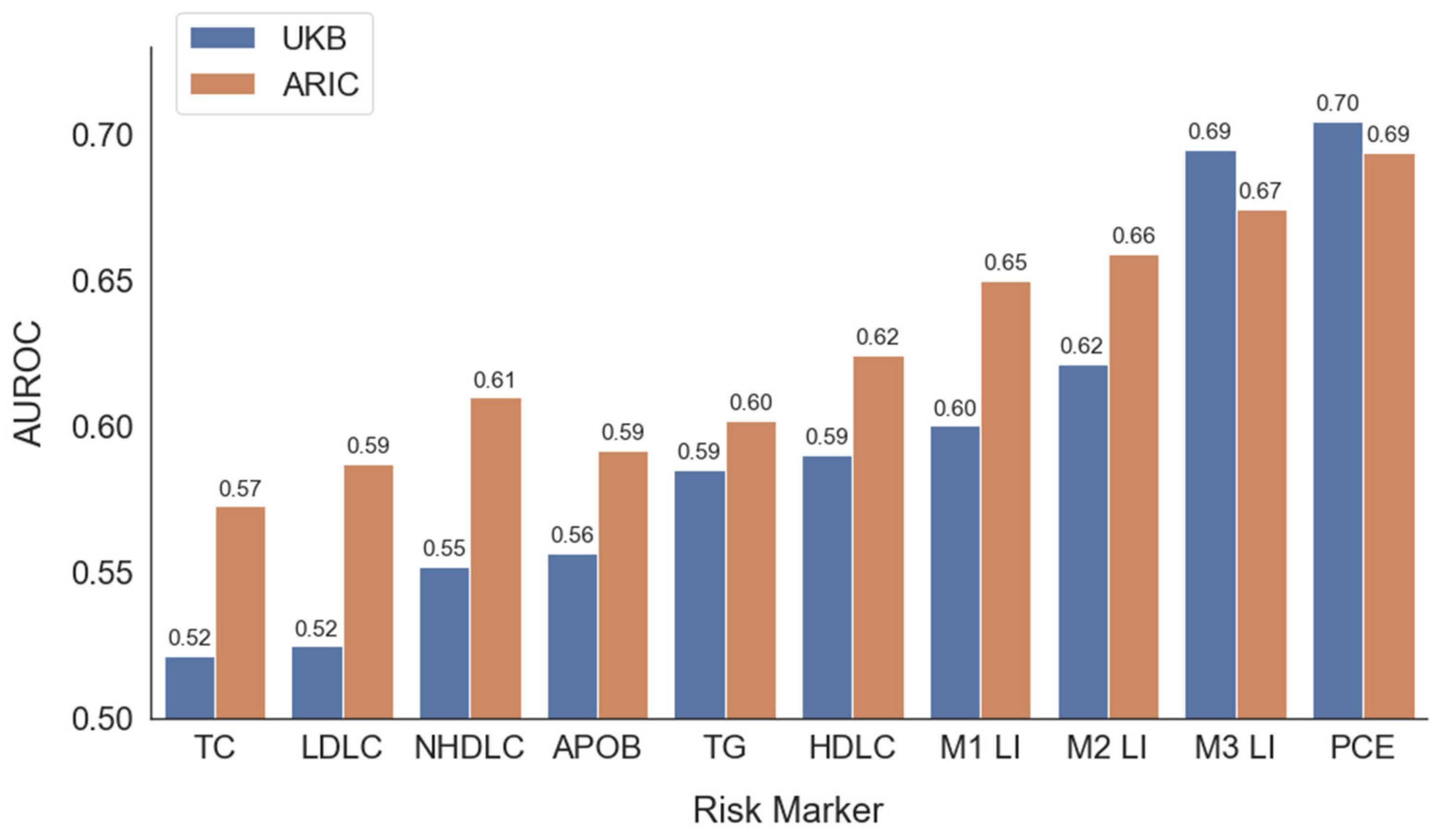

3.3. Predictive Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASCVD | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| apoB | Apolipoprotein B |

| CM | Chylomicrons |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| FLL | Fredrickson, Levy and Lees |

| HDLC | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL | Low-density lipoproteins |

| LDLC | LDL-cholesterol |

| Lp(a) | Lipoprotein (a) |

| PCEs | Pooled cohort equations |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| VLDL | Very low-density lipoproteins |

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| ARIC | Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities |

| MetS | Metabolic syndrome |

| 1/H | Inverse of HDL-C |

| LnTG | Natural logarithm of triglycerides |

| AUROC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

Appendix A

References

- Sachdeva, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Deedwania, P.C.; LaBresh, K.A.; Smith, S.C.; Dai, D.; Hernandez, A.; Fonarow, G.C. Lipid levels in patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease: An analysis of 136,905 hospitalizations in Get with the Guidelines. Am. Heart J. 2009, 157, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faridi, K.F.; Lahan, S.; Budoff, M.J.; Cury, R.C.; Feldman, T.; Pan, A.P.; Fialkow, J.; Nasir, K. Serum Lipoproteins are Associated with Coronary Atherosclerosis in Asymptomatic U.S. Adults Without Traditional Risk Factors. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 101049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; de Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 139, E1082–E1143. [Google Scholar]

- Thanassoulis, G.; Williams, K.; Altobelli, K.K.; Pencina, M.J.; Cannon, C.P.; Sniderman, A.D. Individualized Statin Benefit for Determining Statin Eligibility in the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2016, 133, 1574–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanassoulis, G.; Sniderman, A.D.; Pencina, M.J. A Long-term Benefit Approach vs. Standard Risk-Based Approaches for Statin Eligibility in Primary Prevention. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, D.S.; Levy, R.I.; Lees, R.S. Fat Transport in Lipoproteins—An Integrated Approach to Mechanisms and Disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 1967, 276, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, J.; Couture, P.; Sniderman, A. A diagnostic algorithm for the atherogenic apolipoprotein B dyslipoproteinemias. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 4, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, T.; Dron, J.S.; Selvaraj, M.S.; Trinder, M.; Paruchuri, K.; Urbut, S.M.; Haidermota, S.; Bernardo, R.; Uddin, M.M.; Honigberg, M.C.; et al. Genetic Architecture and Clinical Outcomes of Combined Lipid Disturbances. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olamoyegun, M.; Oluyombo, R.; Asaolu, S. Evaluation of dyslipidemia, lipid ratios, and atherogenic index as cardiovascular risk factors among semi-urban dwellers in Nigeria. Ann. Afr. Med. 2016, 15, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaj, I.; Thalamati, M.; Gowda, M.N.V.; Rao, A. The Role of the Atherogenic Index of Plasma and the Castelli Risk Index I and II in Cardiovascular Disease. Cureus 2024, 16, e74644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remaley, A.T.; Cole, J.; Sniderman, A.D. ApoB is Ready for Prime Time. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 2274–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, G.J.; Thanassoulis, G.; Anderson, T.J.; Barry, A.R.; Couture, P.; Dayan, N.; Francis, G.A.; Genest, J.; Grégoire, J.; Grover, S.A.; et al. 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 1129–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, M.; Wolska, A.; Amar, M.; Ueda, M.; Dunbar, R.; Soffer, D.; Remaley, A.T. Estimated Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Score: An Automated Decision Aid for Statin Therapy. Clin. Chem. 2022, 68, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, M.; Ballout, R.A.; Soffer, D.; Wolska, A.; Wilson, S.; Meeusen, J.; Donato, L.J.; Fatica, E.; Otvos, J.D.; Brinton, E.A.; et al. A new phenotypic classification system for dyslipidemias based on the standard lipid panel. Lipids Health Dis. 2021, 20, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHANES Questionnaires, Datasets, and Related Documentation. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- BioLINCC. Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center. Available online: https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- UK Biobank. Available online: https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Sampson, M.; Ling, C.; Sun, Q.; Harb, R.; Ashmaig, M.; Warnick, R.; Sethi, A.; Fleming, J.K.; Otvos, J.D.; Meeusen, J.W.; et al. A New Equation for Calculation of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Patients with Normolipidemia and/or Hypertriglyceridemia. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 5, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Daniels, S.R.; Donato, K.A.; Eckel, R.H.; Franklin, B.A.; Gordon, D.J.; Krauss, R.M.; Savage, P.J.; Smith, C.S., Jr.; et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005, 112, 2735–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, D.; Pencina, K.; Pencina, M.; Dufresne, L.; Thanassoulis, G.; Sniderman, A.D. Is hypertriglyceridemia a reliable indicator of cholesterol-depleted Apo B particles? J. Clin. Lipidol. 2023, 17, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniderman, A.D.; Thanassoulis, G.; Williams, K.; Pencina, M. Risk of Premature Cardiovascular Disease vs. the Number of Premature Cardiovascular Events. JAMA Cardiol. 2016, 1, 492–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, J.H.; Cordain, L.; Harris, W.H.; Moe, R.M.; Vogel, R. Optimal low-density lipoprotein is 50 to 70 mg/dL: Lower is better and physiologically normal. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 43, 2142–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiyakumar, V.; Pallazola, V.A.; Park, J.; Vakil, R.M.; Toth, P.P.; Lazo-Elizondo, M.; Quispe, R.; Guallar, E.; Banach, M.; Blumenthal, R.S.; et al. Modern prevalence of the Fredrickson-Levy-Lees dyslipidemias: Findings from the Very Large Database of Lipids and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch. Med. Sci. 2020, 16, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, R.; Al-Hijji, M.; Swiger, K.J.; Martin, S.S.; Elshazly, M.B.; Blaha, M.J.; Joshi, P.H.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Sniderman, A.D.; Toth, P.P.; et al. Lipid phenotypes at the extremes of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: The very large database of lipids-9. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2015, 9, 511–518.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallazola, V.A.; Sathiyakumar, V.; Park, J.; Vakil, R.M.; Toth, P.P.; Lazo-Elizondo, M.; Brown, E.; Quispe, R.; Guallar, E.; Banach, M.; et al. Modern prevalence of dysbetalipoproteinemia (Fredrickson-Levy-Lees type III hyperlipoproteinemia). Arch. Med. Sci. 2020, 16, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quispe, R.; Hendrani, A.D.; Baradaran-Noveiry, B.; Martin, S.S.; Brown, E.; Kulkarni, K.R.; Banach, M.; Toth, P.P.; Brinton, E.A.; Jones, S.R.; et al. Characterization of lipoprotein profiles in patients with hypertriglyceridemic Fredrickson-Levy and Lees dyslipidemia phenotypes: The Very Large Database of Lipids Studies 6 and 7. Arch. Med. Sci. 2019, 15, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paquette, M.; Bernard, S.; Baass, A. Dysbetalipoproteinemia is Associated with Increased Risk of Coronary and Peripheral Vascular Disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 108, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegele, R.A.; Ban, M.R.; Hsueh, N.; Kennedy, B.A.; Cao, H.; Zou, G.Y.; Anand, S.; Yusuf, S.; Huff, M.W.; Wang, J. A polygenic basis for four classical Fredrickson hyperlipoproteinemia phenotypes that are characterized by hypertriglyceridemia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 4189–4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiselli, G.; Schaefer, E.J.; Gascon, P.; Brewer, H.B. Type III hyperlipoproteinemia associated with apolipoprotein E deficiency. Science 1981, 214, 1239–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingenbleek, Y.; Van Den Schrieck, H.G.; De Nayer, P.; De Visscher, M. The role of retinol-binding protein in protein-calorie malnutrition. Metabolism 1975, 24, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holewijn, S.; Sniderman, A.D.; den Heijer, M.; Swinkels, D.W.; Stalenhoef, A.F.H.; de Graaf, J. Application and validation of a diagnostic algorithm for the atherogenic apoB dyslipoproteinemias. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 41, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegele, R.A. Combined Lipid Disturbances: More Than the Sum of Their Parts? Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberich, A.J.; Hegele, R.A. A Modern Approach to Dyslipidemia. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 611–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgic, S.; Pencina, K.M.; Pencina, M.J.; Cole, J.; Dufresne, L.; Thanassoulis, G.; Sniderman, A.D. Discordance Analysis of VLDL-C and ApoB in UK Biobank and Framingham Study: A Prospective Observational Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 2244–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniderman, A.D. ApoB vs. non-HDL-C vs. LDL-C as Markers of Cardiovascular Disease. Clin. Chem. 2021, 67, 1440–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniderman, A.D. Differential response of cholesterol and particle measures of atherogenic lipoproteins to LDL-lowering therapy: Implications for clinical practice. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2008, 2, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniderman, A.D.; Pencina, M.; Thanassoulis, G. Limitations in the conventional assessment of the incremental value of predictors of cardiovascular risk. In Current Opinion in Pediatrics; Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015; Volume 26, pp. 210–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sniderman, A.D.; D’Agostino Sr, R.B.; Pencina, M.J. The Role of Physicians in the Era of Predictive Analytics. JAMA 2015, 314, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Pencina, M.J.; Ndumele, C.E.; Rangaswami, J.; Chow, S.L.; Palaniappan, L.P.; Sperling, L.S.; Virani, S.S.; Ho, J.E.; et al. Novel Prediction Equations for Absolute Risk Assessment of Total Cardiovascular Disease Incorporating Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1982–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NHANES | ||||||||

| FEMALE | DIABETIC | SMOKER | ||||||

| 52% | 13% | 23% | ||||||

| COUNT | MEAN | STD | MIN | 25% | 50% | 75% | MAX | |

| AGE | 10,942 | 54 | 8.8 | 40 | 46 | 53 | 61 | 70 |

| BMI | 10,790 | 29 | 6.8 | 14 | 25 | 28 | 33 | 130 |

| SBP | 10,359 | 126 | 18.7 | 64 | 113 | 123 | 136 | 225 |

| TC | 10,942 | 204 | 41.0 | 75 | 177 | 201 | 228 | 704 |

| HDLC | 10,942 | 54 | 16.8 | 6 | 42 | 51 | 63 | 226 |

| NHDLC | 10,942 | 150 | 41.6 | 23 | 121 | 146 | 174 | 685 |

| TG | 10,942 | 134 | 113.8 | 18 | 75 | 107 | 158 | 2742 |

| APOB | 5808 | 99 | 25.2 | 15 | 81 | 97 | 114 | 260 |

| ARIC | ||||||||

| FEMALE | DIABETIC | SMOKER | ASCVD | |||||

| 54% | 10% | 27% | 30% | |||||

| AGE | 14,195 | 54 | 5.8 | 44 | 49 | 54 | 59 | 66 |

| BMI | 14,182 | 28 | 5.4 | 14 | 24 | 27 | 30 | 66 |

| SBP | 14,188 | 121 | 19.0 | 61 | 108 | 119 | 131 | 246 |

| TC | 14,195 | 214 | 41.6 | 48 | 186 | 212 | 239 | 593 |

| HDLC | 14,195 | 52 | 17.0 | 10 | 40 | 49 | 61 | 162 |

| NHDLC | 14,195 | 163 | 43.8 | 10 | 133 | 160 | 190 | 521 |

| TG | 14,195 | 131 | 87.7 | 24 | 79 | 110 | 157 | 1926 |

| APOB | 14,190 | 93 | 28.8 | 12 | 73 | 90 | 110 | 294 |

| UK BIOBANK | ||||||||

| FEMALE | DIABETIC | SMOKER | ASCVD | |||||

| 57% | 2% | 1% | 10% | |||||

| AGE | 354,344 | 56 | 8.1 | 37 | 49 | 56 | 62 | 73 |

| BMI | 353,040 | 27 | 4.6 | 12 | 24 | 26 | 29 | 69 |

| SBP | 353,953 | 137 | 18.7 | 65 | 124 | 136 | 149 | 268 |

| TC | 354,344 | 228 | 41.2 | 58 | 199 | 225 | 253 | 597 |

| HDLC | 354,344 | 57 | 14.7 | 9 | 46 | 55 | 66 | 170 |

| NHDLC | 354,344 | 171 | 39.7 | 25 | 143 | 168 | 195 | 523 |

| TG | 354,344 | 151 | 88.8 | 20 | 90 | 128 | 185 | 998 |

| APOB | 352,608 | 106 | 23.1 | 40 | 90 | 105 | 121 | 200 |

| Phenotype | NonHDL-C (mg/dL) | TG (mg/dL) | HDL-C (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| normolipidemic | 120–175 | 75–160 | 40–60 |

| Proviso: The following do not meet all 3 criteria for normolipidemia | |||

| nth | ≤150 | ≤110 | ≥50 |

| Nth | >150 | ≤110 | ≥50 |

| NTh | >150 | >110 | ≥50 |

| NtH | >150 | ≤110 | <50 |

| nTh | ≤150 | >110 | ≥50 |

| nTH | ≤150 | >110 | <50 |

| ntH | ≤150 | ≤110 | <50 |

| NTH | >150 | >110 | <50 |

| Group | NHANES (%) | ARIC (%) | UK Biobank n (%) | UK Biobank u (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| normolipidemic | 17.9 | 15.2 | 14.8 | 16.6 |

| nth | 24.6 | 18.7 | 14.2 | 20.2 |

| ntH | 7.6 | 6.1 | 2.6 | 10.2 |

| nTh | 4.4 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 2.9 |

| nTH | 7.6 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 9.5 |

| Nth | 8.8 | 10.3 | 14.1 | 9.2 |

| NtH | 2.4 | 6.3 | 1.4 | 2.9 |

| NTh | 8.9 | 8.5 | 24.4 | 8.8 |

| NTH | 17.7 | 26.4 | 20.7 | 19.6 |

| LI | x1 | x2 | x3 | x4 | B0 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | r | θ | φ | NA | −2.371 | 0.3550 | −0.0107 | −0.0268 | NA |

| L2 | L1 | Female | Male | NA | −1.383 | 3.783 | −0.9089 | −0.3693 | NA |

| L3 | L1 | Age | Female | Male | −4.756 | 3.718 | 0.0504 | −0.2605 | 0.2615 |

| CUTOFF | SENSITIVITY | SPECIFICITY | PPV | NPV | F1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Prediction | ||||||

| ARIC Dataset | ||||||

| APOB | 87 mg/dL | 0.66 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.77 | 0.46 |

| LDLC | 131 mg/dL | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.76 | 0.46 |

| TG | 112 mg/dL | 0.6 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.76 | 0.46 |

| NHDLC | 156 mg/dL | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.78 | 0.47 |

| L3 | 26% | 0.72 | 0.53 | 0.4 | 0.82 | 0.51 |

| PCE | 4.1% | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.4 | 0.83 | 0.52 |

| UK Biobank Dataset | ||||||

| APOB | 102 mg/dL | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.91 | 0.2 |

| LDLC | 133 mg/dL | 0.63 | 0.4 | 0.11 | 0.9 | 0.19 |

| TG | 127 mg/dL | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.92 | 0.21 |

| NHDLC | 164 mg/dL | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.91 | 0.2 |

| L3 | 11% | 0.7 | 0.59 | 0.17 | 0.94 | 0.27 |

| PCE | 5.7% | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.17 | 0.94 | 0.28 |

| Risk Enhancer Tests | ||||||

| ARIC Dataset | ||||||

| APOB | 130 mg/dL | 0.11 | 0.92 | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.18 |

| LDLC | 160 mg/dL | 0.3 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 0.36 |

| TG | 175 mg/dL | 0.28 | 0.77 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 0.35 |

| L3 | 37% | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.66 | 0.48 |

| UK Biobank Dataset | ||||||

| APOB | 130 mg/dL | 0.12 | 0.89 | 0.16 | 0.85 | 0.14 |

| LDLC | 160 mg/dL | 0.28 | 0.72 | 0.15 | 0.85 | 0.19 |

| TG | 175 mg/dL | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.16 | 0.86 | 0.23 |

| L3 | 16% | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.18 | 0.87 | 0.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cole, J.; Sampson, M.; Remaley, A.T. Spherical Coordinate System for Dyslipoproteinemia Phenotyping and Risk Prediction. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7557. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217557

Cole J, Sampson M, Remaley AT. Spherical Coordinate System for Dyslipoproteinemia Phenotyping and Risk Prediction. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7557. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217557

Chicago/Turabian StyleCole, Justine, Maureen Sampson, and Alan T. Remaley. 2025. "Spherical Coordinate System for Dyslipoproteinemia Phenotyping and Risk Prediction" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7557. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217557

APA StyleCole, J., Sampson, M., & Remaley, A. T. (2025). Spherical Coordinate System for Dyslipoproteinemia Phenotyping and Risk Prediction. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7557. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217557