Prevalence and Perspectives of Use of Dietary Supplements Among Adult Athletes Visiting Fitness Centers in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Sample Size and Sampling Method

2.3. Construction, Validation, and Reliability of Study Tool

2.4. Ethical Consideration

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

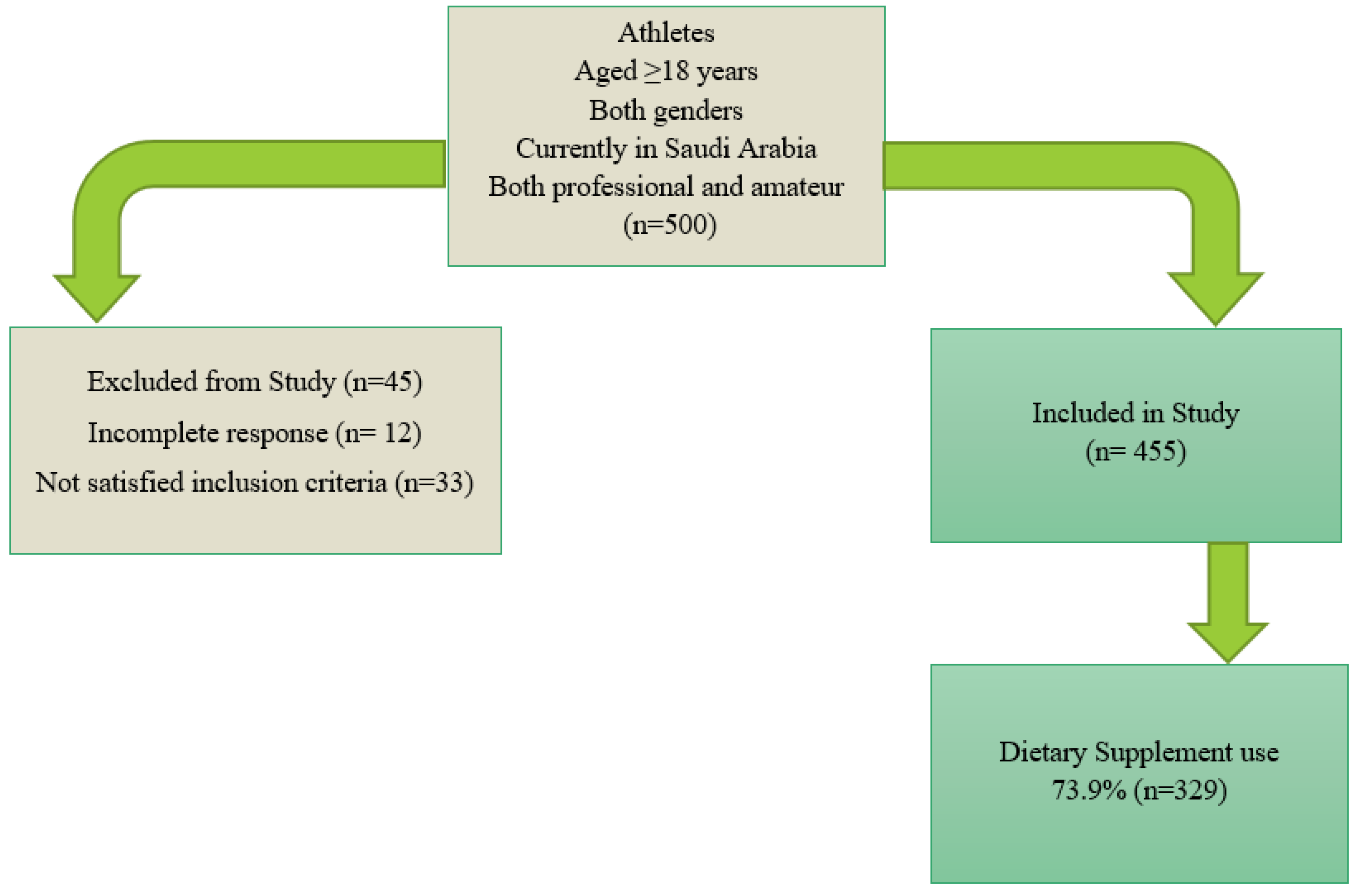

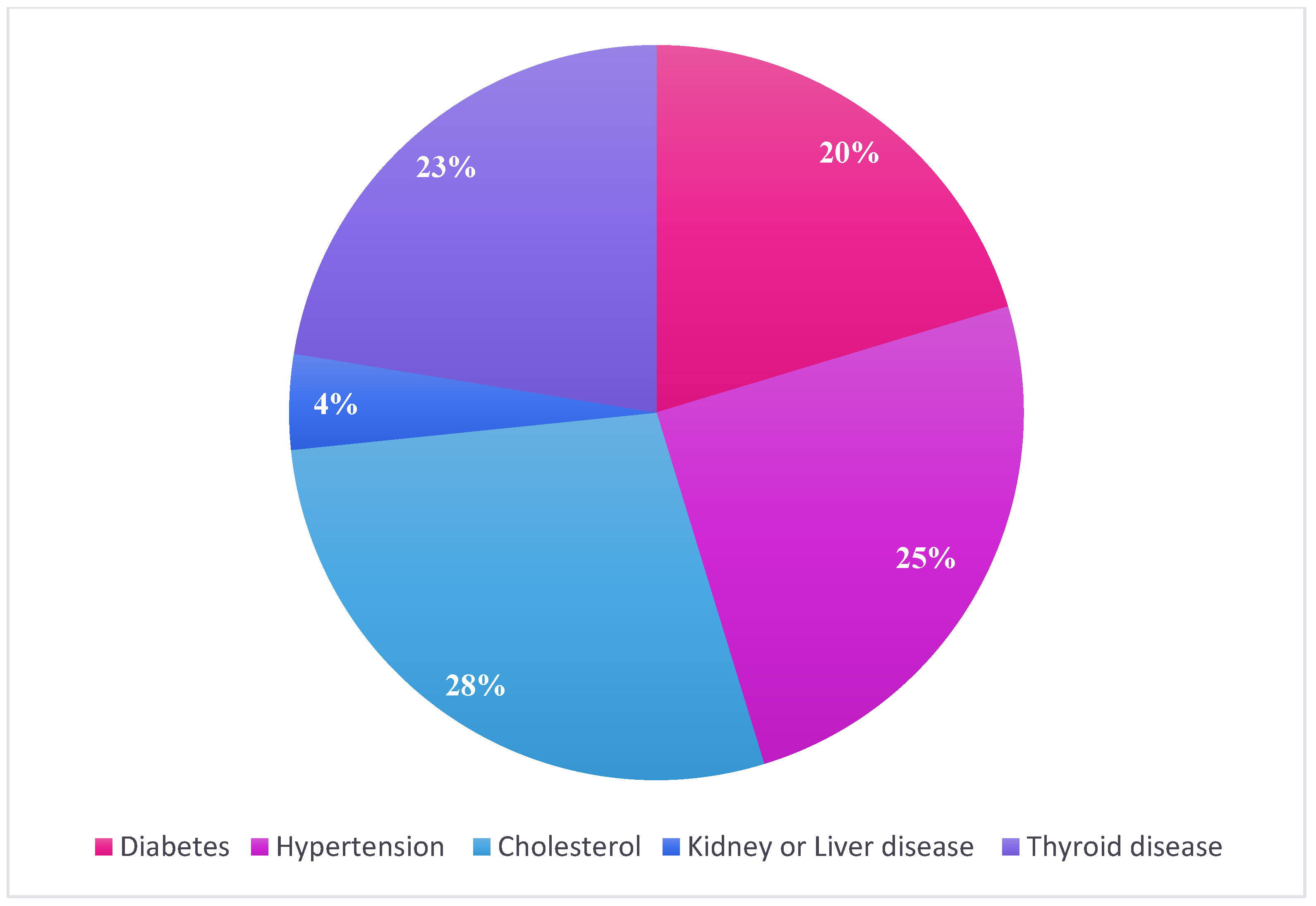

3.1. Participant Recruitment and Characteristics

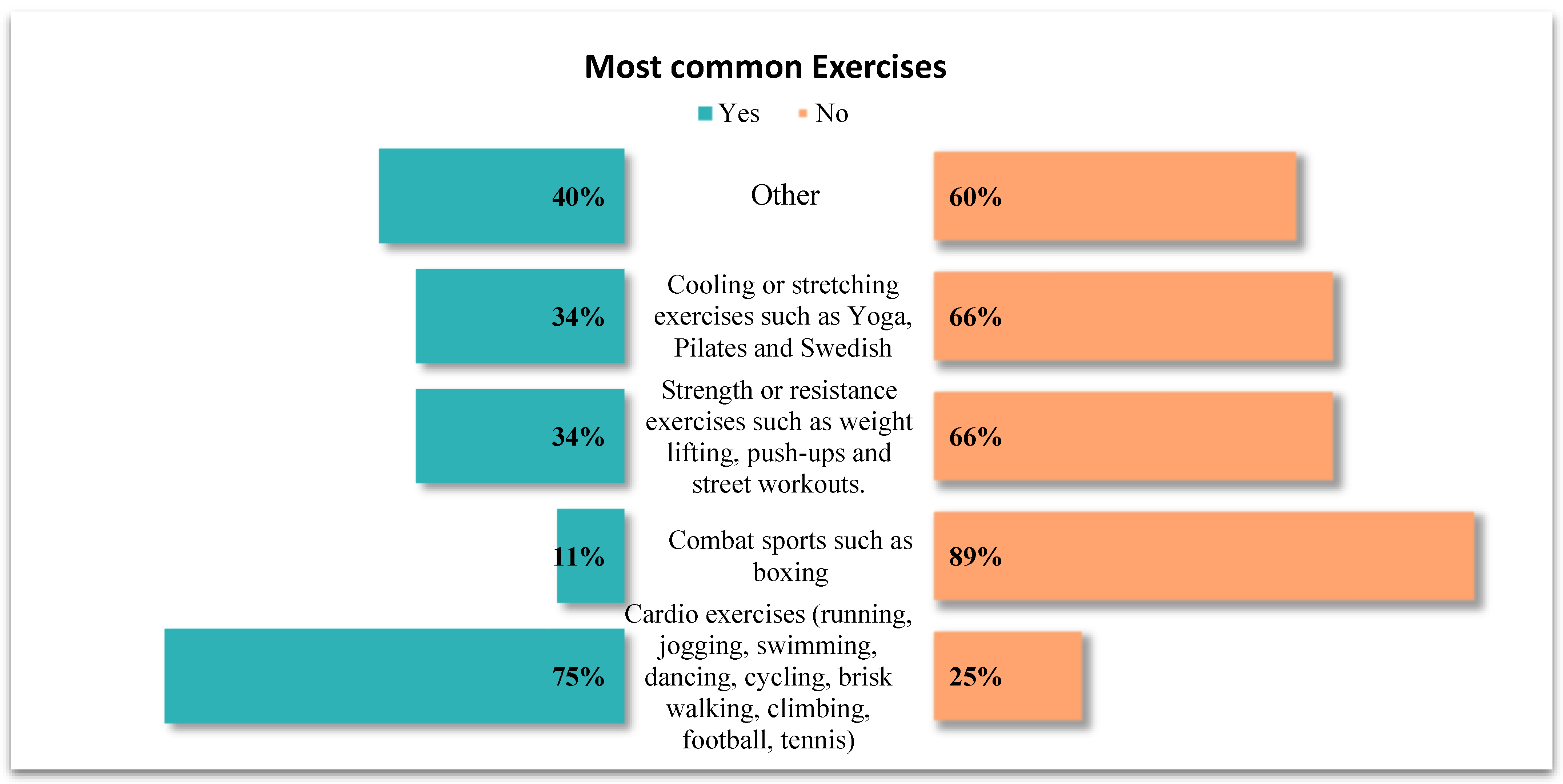

3.2. Sports Club Affiliation and Exercise Patterns

3.3. Dietary Supplement (DS) Use

3.4. Supplementation Practices and Purchasing

3.5. Blood Testing and Supplement Use

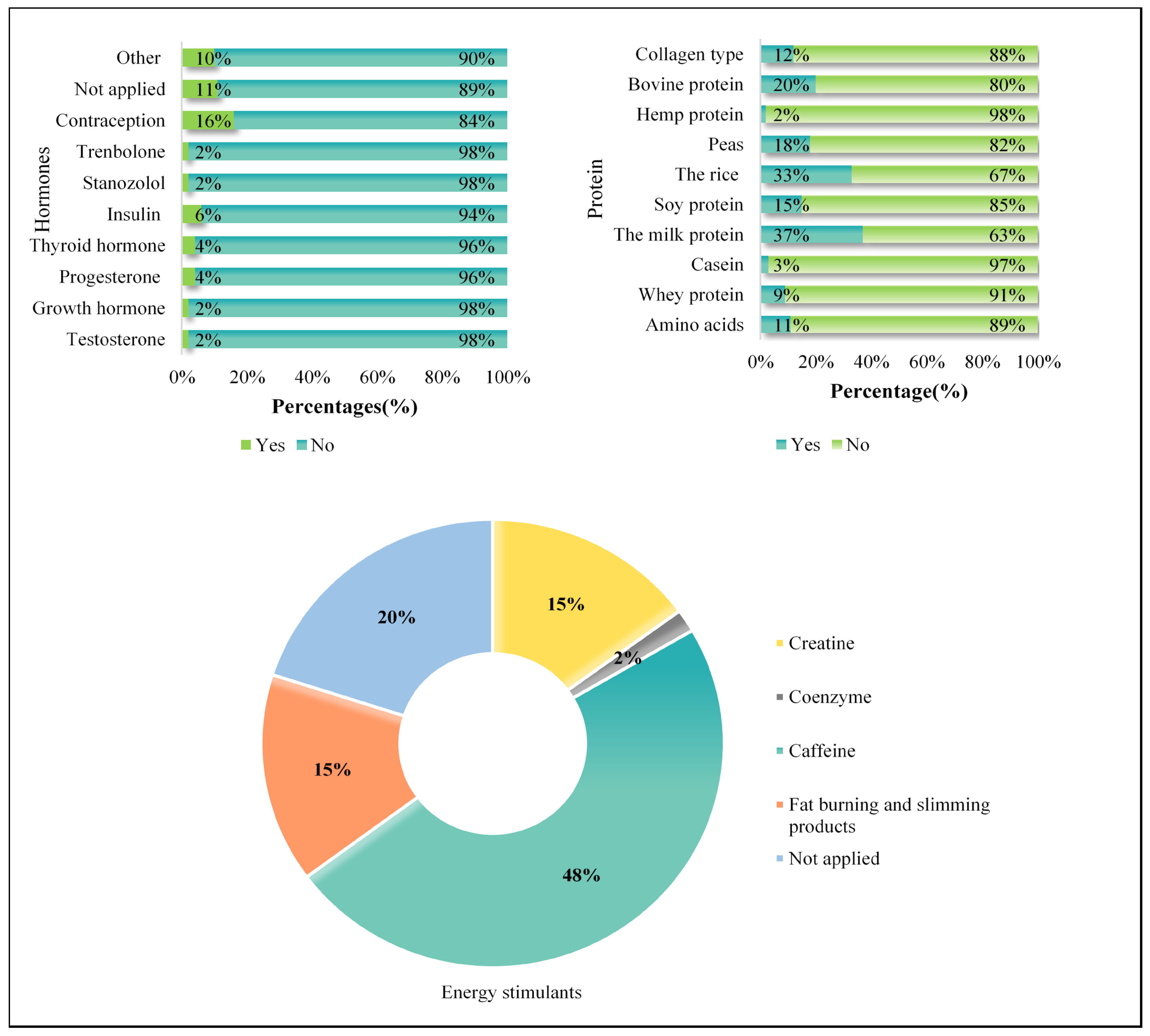

3.6. Use of Hormones, Proteins, and Stimulants

3.7. Perceptions of Supplement Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aljaloud, S.O.; Al-Ghaiheb, A.L.; Khoshhal, K.I.; Konbaz, S.M.; Al Massad, A.; Wajid, S. Effect of athletes’ attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge on doping and dietary supplementation in Saudi sports clubs. J. Musculoskelet. Surg. Res. 2020, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabaiki, I.J.; Bekadi, A.; Bechikh, M.Y. Sports supplements: Use, knowledge, and risks for Algerian athletes. N. Afr. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 4, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KSA Fitness Services Market Outlook to 2027. Available online: https://www.kenresearch.com/industry-reports/ksa-fitness-services-market-revenue (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Babelghaith, S.D.; Sales, I.; Syed, W.; Al-Arifi, M.N. The use of complementary and alternative medicine for functional gastrointestinal disorders among the saudi population. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 102084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagim, A.R.; Harty, P.S.; Erickson, J.L.; Tinsley, G.M.; Garner, D.; Galpin, A.J. Prevalence of adulteration in dietary supplements and recommendations for safe supplement practices in sport. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1239121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.M.; Helms, E.R.; Trexler, E.T.; Fitschen, P.J. Nutritional recommendations for physique athletes. J. Hum. Kinet. 2020, 71, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maughan, R.J.; Burke, L.M.; Dvorak, J.; Larson-Meyer, D.E.; Peeling, P.; Phillips, S.M.; Rawson, E.S.; Walsh, N.P.; Garthe, I.; Geyer, H.; et al. IOC consensus statement: Dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.C.; Eshetie, T.; Gray, S.; Marcum, Z. Dietary supplement use in middle-aged and older adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2022, 26, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, N.M. Prohibited contaminants in dietary supplements. Sports Health 2018, 10, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Garthe, I.; Maughan, R.J. Athletes and supplements: Prevalence and perspectives. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhuharov, V.R.; Ivanov, K.; Ivanova, S. Dietary supplements as source of unintentional doping. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8387271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzejska, R.E. Dietary supplements—For whom? The current state of knowledge about the health effects of selected supplement use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakkar, S.; Anklam, E.; Xu, A.; Ulberth, F.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Hugas, M.; Sarma, N.; Crerar, S.; Swift, S.; et al. Regulatory landscape of dietary supplements and herbal medicines from a global perspective. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 114, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, J.; Mallick, M.; El Khoury, D. Prevalence of Dietary Supplement Use among Athletes Worldwide: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrack, M.; Fredericson, M.; Dizon, F.; Tenforde, A.; Kim, B.; Kraus, E.; Kussman, A.; Singh, S.; Nattiv, A. Dietary supplement use according to sex and triad risk factors in collegiate endurance runners. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, P.; Ring, C.; Kavussanu, M. Athletes using ergogenic and medical sport supplements report more favourable attitudes to doping than non-users. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2021, 24, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, M.C.; Kerr, D.A.; Binnie, M.J.; Eaton, E.; Wood, C.; Stenvers, T.; Gucciardi, D.F.; Goodman, C.; Ducker, K.J. Supplement use and behaviors of athletes affiliated with an Australian state-based sports institute. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2019, 29, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRuthia, Y.; Balkhi, B.; Alrasheed, M.; Altuwaijri, A.; Alarifi, M.; Alzahrani, H.; Mansy, W. Use of dietary and performance-enhancing supplements among male fitness center members in Riyadh: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saeed, A.A.; Almaqhawi, A.; Ibrahim, S. Nutritional Supplements Intake by Gym Participants in Saudi Arabia: A National Population-Based Study. Int. J. Pharm. Phytopharm. Res 2020, 10, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Alfawaz, H.A.; Krishnaswamy, S.; Al-Faifi, L.; Atta, H.A.B.; Al-Shayaa, M.; Alghanim, S.A.; Al-Daghri, N.M. Awareness and attitude toward use of dietary supplements and the perceived outcomes among Saudi adult male members of fitness centers in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljebeli, S.; Albuhairan, R.; Ababtain, N.; Almazroa, T.; Alqahtani, S.; Philip, W. The prevalence and awareness of dietary supplement use among saudi women visiting fitness centers in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e41031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohammadi, A.M.; Edriss, A.M.; Enani, T.T. Anabolic–androgenic steroids and dietary supplements among resistance trained individuals in western cities of Saudi Arabia. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooijman, A.; Canfield, C. Cultivating the conditions for care: It’s all about trust. Front Health Serv. 2024, 4, 1471183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Syed Snr, W.; Bashatah, A.; A Al-Rawi, M.B. Evaluation of knowledge of food–drug and alcohol–drug interactions among undergraduate students at king Saud University–an observational study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Professional Athlete. Available online: https://www.encyclopedia.com/economics/news-and-education-magazines/professional-athlete (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Wikipedia. Amateur Sports. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amateur_sports (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Syed, W.; Al-Rawi, M.B.A. Assessment of Sleeping Disorders, Characteristics, and Sleeping Medication Use Among Pharmacy Students in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Quantitative Study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2023, 29, e942147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, W.; Samarkandi, O.A.; Sadoun, A.A.; Bashatah, A.S.; Al-Rawi, M.B.A.; Alharbi, M.K. Prevalence, beliefs, and the practice of the use of herbal and dietary supplements among adults in Saudi Arabia: An observational study. Inq. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2022, 59, 00469580221102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raosoft Samplesize Calculator. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Saudi Olympic Committee Reports 52% Increase in Female Athlete Registrations in 2023. 2024. Available online: https://saudigazette.com.sa/article/639373/SAUDI-ARABIA/Saudi-Olympic-Committee-reports-52-increase-in-female-athlete-registrations-in-2023 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Alhussain, M.H.; Abdulhalim, W.S.; Al-harbi, L.N.; Binobead, M.A. Prevalence and Attitudes Towards Using Protein Supplements Among Female Gym Users: An Online Survey. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 18, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allehdan, S.; Hasan, M.; Perna, S.; Al-Mannai, M.; Alalwan, T.; Mohammed, D.; Almosawi, M.; Hoteit, M.; Tayyem, R. Prevalence, knowledge, awareness, and attitudes towards dietary supplements among Bahraini adults: A cross-sectional study. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2023, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, E.; Sato, Y.; Umegaki, K.; Chiba, T. The Prevalence of Dietary Supplement Use among College Students: A Nationwide Survey in Japan. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samreen, S.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Wajid, S.; Mothana, R.A.; Almarfadi, O.M. Prevalence and use of dietary supplements among pharmacy students in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, M.; Camacho, C.B.; Daher, J.; El Khoury, D. Dietary Supplements: A Gateway to Doping? Nutrients 2023, 15, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, F.; Yazdani, A.; Nematolahi, F.; Hosseini-Roknabadi, S.M.; Sharifi, N. Prevalence of supplement usage and related attitudes and reasons among fitness athletes in the gyms of Kashan and its relationship with feeding behavior: A cross-sectional study. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa-Rufino, C.; Pareja-Galeano, H.; Martínez-Ferrán, M. Dietary Supplement Use in Competitive Spanish Football Players and Differences According to Sex. Nutrients 2025, 17, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshammari, S.A.; AlShowair, M.A.; AlRuhaim, A. Use of hormones and nutritional supplements among gyms’ attendees in Riyadh. J. Fam. Community Med. 2017, 24, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, N.M.; Aziz, F.; Blair, I.; Grivna, M.; Adam, B.; Loney, T. Prevalence of, and factors associated with health supplement use in Dubai, United Arab Emirates: A population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muwonge, H.; Zavuga, R.; Kabenge, P.A.; Makubuya, T. Nutritional supplement practices of professional Ugandan athletes: A cross-sectional study. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2017, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, A.K.; Albassam, R.S. Assessment of General and Sports Nutrition Knowledge, Dietary Habits, and Nutrient Intake of Physical Activity Practitioners and Athletes in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, S.; El Koofy, N.; Moawad, E.M.I. Patterns of nutrition and dietary supplements use in young Egyptian athletes: A community-based cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhashem, A.M.; Alghamdi, R.A.; Alamri, R.S.; Alzhrani, W.S.; Alrakaf, M.S.; Alzaid, N.A.; Alzaben, A.S. Prevalence, patterns, and attitude regarding dietary supplement use in Saudi Arabia: Data from 2019. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valavanidis, A. Dietary supplements: Beneficial to human health or just peace of mind? a critical review on the issue of benefit/risk of dietary supplements. Pharmakeftiki 2016, 28, 60–83. [Google Scholar]

- Alshehri, A.A.; Alqahtani, S.; Aldajani, R.; Alsharabi, B.; Alzahrani, W.; Alguthami, G.; Khawagi, W.Y.; Arida, H. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Dietary Supplement Use in Western Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, M.S.; Benjamin, C.L.; Casa, D.J.; Sekiguchi, Y. Importance of Electrolytes in Exercise Performance and Assessment Methodology After Heat Training: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbay, S.; Ulupınar, S.; Gençoğlu, C.; Ouergui, I.; Öget, F.; Yılmaz, H.H.; Kishalı, N.F.; Kıyıcı, F.; Asan, S.; Uçan, İ.; et al. Effects of ramadan intermittent fasting on performance, physiological responses, and bioenergetic pathway contributions during repeated sprint exercise. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1322128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlTarrah, D.; ElSamra, Z.; Daher, W.; AlKhas, A.; Alzafiri, L. A cross-sectional study of self-reported dietary supplement use, associated factors, and adverse events among young adults in Kuwait. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, S.; Atan, R.M.; Sahin, N.; Ergul, Y. Evaluation of night eating syndrome and food addiction in esports players. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, A.I.; Shehab, N.; Weidle, N.J.; Lovegrove, M.C.; Wolpert, B.J.; Timbo, B.B.; Mozersky, R.P.; Budnitz, D.S. Emergency department visits for adverse events related to dietary supplements. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1531–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garthe, I.; Ramsbottom, R. Elite athletes, a rationale for the use of dietary supplements: A practical approach. PharmaNutrition 2020, 14, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 62 (13.9) |

| Female | 383 (86.1) * |

| City | |

| Riyadh | 380 (85.4) * |

| Dammam | 6 (1.3) |

| Jeddah | 12 (2.7) |

| Makah | 8 (1.8) |

| Medina | 5 (1.1) |

| Hail | 5 (1.1) |

| Other | 29 (6.5) |

| Nationality | |

| Saudi | 436 (98.0) * |

| Non-Saudi | 9 (2.0) |

| Age | |

| 18–24 Years | 49 (11.0) |

| 25–35 Years | 101 (22.7) |

| 36–40 Years | 41 (9.2) |

| 41–45 Years | 65 (14.6) |

| >46 Years and above | 189 (42.5) * |

| Occupation | |

| Student | 45 (10.1) |

| Government sector employee | 142 (31.9) |

| Military | 8 (1.8) |

| Private sector employee | 49 (11.0) |

| Free business | 43 (9.7) |

| Other | 158 (35.5) * |

| Education Level | |

| Middle school or less | 10 (2.2) |

| High school | 74 (16.6) |

| University | 298 (67.0) * |

| Postgraduate | 63 (14.2) |

| Health problem | |

| Yes | 142 (31.9) |

| No | 303 (68.1) * |

| Are you deficient in vitamins and minerals? | |

| Yes | 231 (51.9) |

| Don’t know | 117 (26.3) |

| No | 97 (21.8) |

| Do you smoke? | |

| Yes | 31 (7.0) |

| No | 404 (90.8) * |

| Ex. Smoker | 10 (2.2) |

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Your sports club is affiliated with | |

| Governmental entity | 29 (6.5) |

| Private hospital | 8 (1.8) |

| Independent private club | 177 (39.8) |

| Other | 231 (51.9) * |

| Does your sports club have a license from the municipality? | |

| Yes | 204 (45.8) * |

| I don’t know | 187 (42.0) |

| No | 54 (12.1) |

| Besides specific training related to your sport, what are other reasons for your exercise? (n = 22 valid response) # | |

| Lifestyle | 1 (4.5) |

| To improve health | 6 (27.3) |

| To improve body shape | 1 (4.5) |

| To improve health and body shape, and weight loss | 1 (4.5) |

| To build muscle | 7 (31.8) * |

| For weight loss only | 5 (22.7) |

| Hobby | 1 (4.5) |

| Exercise | |

| Daily | 33 (7.4) |

| 4–5 times a week | 78 (17.5) |

| 2–3 times a week | 147 (33.0) * |

| Once a week | 100 (22.5) |

| Rarely | 87 (19.6) |

| Variables | Yes n (%) | No n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Using vitamins or dietary supplements | 329 (73.9) * | 116 (26.1) |

| Reasons for use of dietary supplements | ||

| To increase physical strength | 151 (33.9) | 294 (66.1) |

| For muscle building and bodybuilding | 101 (22.7) | 344 (77.3) |

| Increase activity and energy | 204 (45.8) | 241 (54.2) |

| Deficiency in vitamins and minerals | 276 (62.0) | 169 (38.0) |

| For weight loss | 92 (20.7) | 353 (79.3) |

| Muscle drying | 24 (5.4) | 421 (94.6) |

| To reduce injuries | 82 (18.4) | 363 (81.6) |

| Not applied | 53 (11.9) | 392 (88.1) |

| Other | 51 (11.5) | 394 (88.5) |

| Reasons for not using dietary supplements | ||

| I don’t need it | 322 (72.4) | 123 (27.6) |

| Unhealthy | 78 (17.5) | 367 (82.5) |

| I don’t know much about it | 142 (31.9) | 303 (68.1) |

| Expensive | 124 (27.9) | 321 (72.1) |

| Other | 97 (21.8) | 348 (78.2) |

| Types of dietary supplements | ||

| Vitamins and minerals | 344 (77.3) | 101 (22.7) |

| Fish oils (omega-3, omega-6) | 255 (57.3) | 190 (42.7) |

| Herbs (ginseng, ginkgo, ephedra) | 58 (13.0) | 387 (87.0) |

| Stimulants such as amphetamines | 23 (5.2) | 422 (94.8) |

| Energy drinks like Red Bull | 28 (6.3) | 417 (93.7) |

| Healthy drinks | 149 (33.5) | 296 (66.5) |

| Diuretics such as fursamide, metolazone, and bendrflumethiazide | 16 (3.6) | 429 (96.4) |

| Energy and performance stimulants (creatine, caffeine, coenzyme, fat-burning and slimming products) | 62 (13.9) | 383 (86.1) |

| Hormones (testosterone, growth hormone, progesterone, thyroid hormone) | 31 (7.0) | 414 (93.0) |

| Proteins (amino acids and casein) | 69 (15.5) | 376 (84.5) |

| Not applicable | 8 (1.8) | 23 (5.2) |

| Side affects you experience while using dietary supplements | ||

| Changes in attitude and behavior, e.g., aggressiveness | 18 (4.0) | 427 (96.0) |

| Appearance of acne | 41 (9.2) | 404 (90.8) |

| Protrusion in breast | 21 (4.7) | 424 (95.3) |

| Increase in height | 14 (3.1) | 431 (96.9) |

| Frequent urination | 80 (18.0) | 365 (82.0) |

| Oliguria | 13 (2.9) | 432 (97.1) |

| Change in the color or smell of urine | 122 (27.4) | 323 (72.6) |

| Hair loss | 39 (8.8) | 406 (91.2) |

| Noticeable change in sexual activity | 43 (9.7) | 402 (90.3) |

| Frequent forgetfulness or changes in memory | 42 (9.4) | 403 (90.6) |

| Lack of sleep | 49 (11.0) | 396 (89.0) |

| No side effects | 145 (32.6) | 300 (67.4) |

| Other | 43 (9.7) | 402 (90.3) |

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Regular use of dietary supplements | |

| Yes | 115 (25.8) |

| No | 238 (53.5) |

| Not applicable | 92 (20.7) |

| Method of Use | |

| Oral | 349 (78.4) * |

| Intravenous | 2 (0.4) |

| Not applied | 90 (20.2) |

| Other | 4 (0.9) |

| How often do you take daily dietary supplements? | |

| Once a day | 181 (40.7) * |

| Twice a day | 24 (5.4) |

| Three times a day | 8 (1.8) |

| As needed | 119 (26.7) |

| Not applied | 102 (22.9) |

| Other | 11 (2.5) |

| On what basis was the dietary supplement dose you need determined? | |

| Based on my body weight | 34 (7.6) |

| By a nutritionist | 51 (11.5) |

| By my athletic trainer | 7 (1.6) |

| By a specialist doctor or pharmacist | 156 (35.1) * |

| I followed the instructions on the product packaging | 72 (16.2) |

| Not applied | 119 (26.7) |

| Other | 6 (1.3) |

| How committed are you to using dietary supplements? | |

| Continuously throughout the year | 83 (18.7) |

| Temporarily (a week to a month) | 79 (17.8) |

| Temporarily until the desired results are obtained | 150 (33.7) * |

| Not applied | 124 (27.9) |

| Other | 9 (1.9) |

| Whose advice you take on how to use dietary supplements? | |

| Medical | 183 (41.1) * |

| Sport trainer | 14 (3.1) |

| Nutrition specialist | 38 (8.5) |

| Myself | 101 (22.7) |

| Not applied | 103 (23.1) |

| Other | 6 (1.4) |

| Items | Yes n (%) | No n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Where do you buy dietary supplements? | ||

| Pharmacy | 292 (65.6) | 153 (34.4) |

| Dietary supplement stores | 104 (23.4) | 341 (76.6) |

| Internet sites | 186 (41.8) | 259 (58.2) |

| Sports coach | 18 (4.0) | 427 (96.0) |

| Unknown shops | 14 (3.1) | 431 (96.9) |

| Not applied | 61 (13.7) | 384 (86.3) |

| Other | 27 (6.1) | 418 (93.9) |

| Condition of the dietary supplement product when it was purchased | ||

| In the original packaging | 348 (78.2) | 97 (21.8) |

| Not in its original packaging | 13 (2.9) | 432 (97.1) |

| There is no writing on the packaging indicating its ingredients | 24 (5.4) | 421 (94.6) |

| The information on the packaging is incomprehensible | 32 (7.2) | 413 (92.8) |

| Not applied | 62 (13.9) | 383 (86.1) |

| Other | 32 (7.2) | 413 (92.8) |

| Where do you get your information about dietary supplements? | ||

| Sports coach | 66 (14.8) | 379 (85.2) |

| A specialist doctor or pharmacist | 256 (57.5) | 189 (42.5) |

| Nutrition specialist | 174 (39.1) | 271 (60.9) |

| Friends | 134 (30.1) | 311 (69.9) |

| Ads | 73 (16.4) | 372 (83.6) |

| Not applied | 61 (13.7) | 384 (86.3) |

| Other | 57 (12.8) | 388 (87.2) |

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Did you take a blood test before taking the supplements? | |

| Yes | 255 (57.3) * |

| No | 108 (24.3) |

| Not applied | 82 (18.4) |

| The period between each blood test | |

| Month | 21 (4.7) |

| Three months | 52 (11.7) |

| Six months | 89 (20.0) |

| Every year | 91 (20.4) |

| Not applied | 182 (40.9) * |

| Other | 10 (2.2) |

| Did you take a blood test before taking the supplements? | |

| Yes | 68 (15.3) |

| No | 209 (47.0) * |

| I haven’t stopped using it | 35 (7.9) |

| Not applied | 133 (29.9) |

| Items | Strongly Agree n (%) | Agree n (%) | Neutral n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Strongly Disagree n (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS increase my health and my physical structure | 96 (21.6) | 176 (39.6) | 126 (28.3) | 34 (7.6) | 13 (2.9) | 3.69 ± 0.98 |

| DS available in stores and commercial markets have been previously examined and confirmed to be safe to use | 58 (13.0) | 137 (30.8) | 165 (37.1) | 65 (14.6) | 20 (4.5) | 3.33 ± 1.02 |

| DS provide me with vigor and energy | 75 (16.9) | 176 (39.6) | 140 (31.5) | 44 (9.9) | 10 (2.2) | 3.59 ± 0.96 |

| DS increase my ability to perform exercises | 72 (16.2) | 165 (37.1) | 155 (34.8) | 43 (9.7) | 10 (2.2) | 3.55 ± 0.95 |

| DS increase my concentration | 60 (13.5) | 153 (34.4) | 168 (37.8) | 55 (12.4) | 9 (2.0) | 3.45 ± 0.94 |

| Protein supplementation is essential for a toned body | 50 (11.2) | 118 (26.5) | 187 (42.0) | 70 (15.7) | 20 (4.5) | 3.24 ± 0.99 |

| There is no difference between taking DS with a prescription or without a prescription | 23 (5.2) | 52 (11.7) | 165 (37.1) | 157 (35.3) | 48 (10.8) | 2.65 ± 0.99 |

| Taking food supplements replaces eating enough and varied food | 27 (6.1) | 37 (8.3) | 116 (26.1) | 173 (38.9) | 92 (20.7) | 2.40 ± 1.09 |

| I advise others to take DS | 40 (9.0) | 112 (25.2) | 194 (43.6) | 80 (18.0) | 19 (4.3) | 3.17 ± 0.97 |

| Not taking DS will reduce my athletic performance and physical activity | 27 (6.1) | 79 (17.8) | 181 (40.7) | 126 (28.3) | 32 (7.2) | 2.87 ± 0.99 |

| Sports clubs should provide awareness lectures on DS | 152 (34.2) | 137 (30.8) | 101 (22.7) | 49 (11.0) | 6 (1.3) | 3.85 ± 1.05 |

| The use of DS is a negative phenomenon that must be addressed | 33 (7.4) | 62 (13.9) | 197 (44.3) | 114 (25.6) | 39 (8.8) | 2.86 ± 1.01 |

| Variables | n | Mean | T | F | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 62 | 37.65 ± 7.67 | −1.164 | 0.245 * | |

| Female | 383 | 38.83 ± 7.36 | |||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 24 Years and below | 49 | 37.51 ± 7.81 | 2.515 | 0.041 † | |

| 25–35 Years | 101 | 38.94 ± 7.03 | |||

| 36–40 Years | 41 | 40.85 ± 7.85 | |||

| 41–45 Years | 65 | 36.69 ± 8.93 | |||

| 46 Years and above | 189 | 39.01 ± 6.68 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aljohar, H.I.; Almusharraf, H.F.; Alhabardi, S. Prevalence and Perspectives of Use of Dietary Supplements Among Adult Athletes Visiting Fitness Centers in Saudi Arabia. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207410

Aljohar HI, Almusharraf HF, Alhabardi S. Prevalence and Perspectives of Use of Dietary Supplements Among Adult Athletes Visiting Fitness Centers in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207410

Chicago/Turabian StyleAljohar, Haya I., Hajar F. Almusharraf, and Samiah Alhabardi. 2025. "Prevalence and Perspectives of Use of Dietary Supplements Among Adult Athletes Visiting Fitness Centers in Saudi Arabia" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207410

APA StyleAljohar, H. I., Almusharraf, H. F., & Alhabardi, S. (2025). Prevalence and Perspectives of Use of Dietary Supplements Among Adult Athletes Visiting Fitness Centers in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7410. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207410