The Impact of Ursodeoxycholic Acid on Fetal Cardiac Function in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Study (GUARDS Trial)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

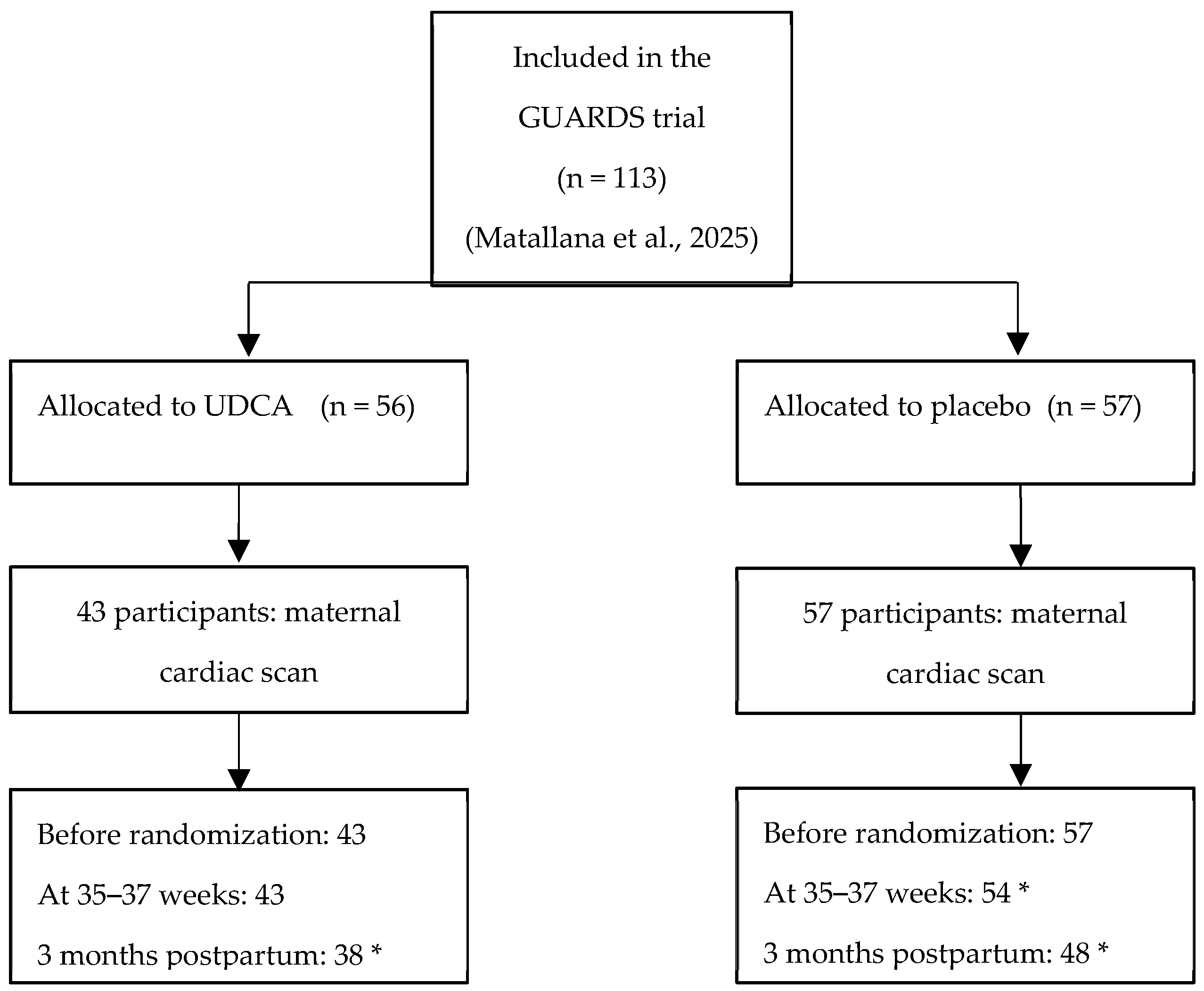

2.1. Study Design and Participants

Sample Size Estimation

2.2. Maternal and Fetal Characteristics

2.3. Fetal Cardiac Functional Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Comparison of Cardiac Indices During the Study

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Results in the Context of What We Know

Fetal Cardiac Changes in GDM

4.3. UDCA and the Fetal Heart

4.4. Clinical and Research Implications

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McIntyre, H.D.; Kampmann, U.; Clausen, T.D.; Laurie, J.; Ma, R.C.W. Gestational Diabetes: An Update 60 Years After O’Sullivan and Mahan. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 110, e19–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, S.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, H.; Long, X.; Ye, F.; Luo, W.; Dai, Y.; Tu, S.; et al. Gestational Diabetes and Future Cardiovascular Diseases: Associations by Sex-Specific Genetic Data. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 5156–5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, J.; Semmler, J.; Coronel, C.; Velicu-Scraba, O.; Coronel, C.; Matallana, C.d.P.; Georgiopoulos, G.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Charakida, M. Paired Maternal and Fetal Cardiac Functional Measurements in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus at 35–36 Weeks’ Gestation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, 574.e1–574.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovera, L.; Zaharia, M.; Jachymski, T.; Velicu-Scraba, O.; Coronel, C.; de Paco Matallana, C.; Georgiopoulos, G.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Charakida, M. Impact of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus on Fetal Cardiac Morphology and Function: Cohort Comparison of Second- and Third-Trimester Fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 57, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huluta, I.; Wright, A.; Cosma, L.M.; Hamed, K.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Charakida, M. Fetal Cardiac Function at Midgestation in Women Who Subsequently Develop Gestational Diabetes. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges Manna, L.; Papacleovoulou, G.; Flaviani, F.; Pataia, V.; Qadri, A.; Abu-Hayyeh, S.; McIlvride, S.; Jansen, E.; Dixon, P.; Chambers, J.; et al. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Improves Feto-Placental and Offspring Metabolic Outcomes in Hypercholanemic Pregnancy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly-O’Donnell, B.; Ferraro, E.; Tikhomirov, R.; Nunez-Toldra, R.; Shchendrygina, A.; Patel, L.; Wu, Y.; Mitchell, A.L.; Endo, A.; Adorini, L.; et al. Protective Effect of UDCA against IL-11-Induced Cardiac Fibrosis Is Mediated by TGR5 Signalling. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1430772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miragoli, M.; Kadir, S.H.S.A.; Sheppard, M.N.; Salvarani, N.; Virta, M.; Wells, S.; Lab, M.J.; Nikolaev, V.O.; Moshkov, A.; Hague, W.M.; et al. A Protective Antiarrhythmic Role of Ursodeoxycholic Acid in an In Vitro Rat Model of the Fetal Heart. J. Hepatol. 2011, 54, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyisoy, Ö.G.; Demirci, O.; Taşdemir, Ü.; Özdemir, M.; Öcal, A.; Kahramanoğlu, Ö. Effect of Maternal Ursodeoxycholic Acid Treatment on Fetal Atrioventricular Conduction in Patients with Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2024, 51, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, F.; Hasan, A.; Alvarez-Laviada, A.; Miragoli, M.; Bhogal, N.; Wells, S.; Poulet, C.; Chambers, J.; Williamson, C.; Gorelik, J. The Protective Effect of Ursodeoxycholic Acid in an In Vitro Model of the Human Fetal Heart Occurs via Targeting Cardiac Fibroblasts. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2016, 120, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeyemi, O.; Alvarez-Laviada, A.; Schultz, F.; Ibrahim, E.; Trauner, M.; Williamson, C.; Gliukhov, A.V.; Gorelik, J. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Prevents Ventricular Conduction Slowing and Arrhythmia by Restoring T-Type Calcium Current in the Fetal Heart. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly-O’Donnell, B.; Ferraro, E.; Brody, R.; Tikhomirov, R.; Mansfield, C.; Williamson, C.; Trayanova, N.; Ng, F.S.; Gorelik, J. Protective Effect of Ursodeoxycholic Acid upon the Post-Myocardial Infarction Heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 12, cvaf133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matallana, C.P.; Blanco-Carnero, J.E.; Company Calabuig, A.; Fernandez, M.; Lewanczyk, M.; Burton, M.; Yang, X.; Mitchell, A.L.; Lovgren-Sandblom, A.; Marschall, H.-U.; et al. Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Impact of Ursodeoxycholic Acid on Glycemia in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: The GUARDS Trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2025, 7, 101732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, A.; Mazer Zumaeta, A.; Syngelaki, A.; Akolekar, R.; Nicolaides, K.H. Ultrasonographic Estimation of Fetal Weight: Development of New Model and Assessment of Performance of Previous Models. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 52, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaides, K.H.; Wright, D.; Syngelaki, A.; Wright, A.; Akolekar, R. Fetal Medicine Foundation Fetal and Neonatal Population Weight Charts. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 52, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crispi, F.; Gratacós, E. Fetal Cardiac Function: Technical Considerations and Potential Research and Clinical Applications. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2012, 32, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Andrade, E.; López-Tenorio, J.; Figueroa-Diesel, H.; Sanin-Blair, J.; Carreras, E.; Cabero, L.; Gratacos, E. A Modified Myocardial Performance (Tei) Index Based on the Use of Valve Clicks Improves Reproducibility of Fetal Left Cardiac Function Assessment. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 26, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Version 2.15.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Vasavan, T.; Deepak, S.; Jayawardane, I.A.; Lucchini, M.; Martin, C.; Geenes, V.; Yang, J.; Lövgren-Sandblom, A.; Seed, P.T.; Chambers, J.; et al. Fetal Cardiac Dysfunction in Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy Is Associated with Elevated Serum Bile Acid Concentrations. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivers, S.; Ovadia, C.; Vasavan, T.; Lucchini, M.; Hayes-Gill, B.; Pini, N.; Fifer, W.P.; Williamson, C. Fetal Heart Rate Analysis in Pregnancies Complicated by Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Multicentre Observational Study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2025, 132, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depla, A.L.; De Wit, L.; Steenhuis, T.J.; Slieker, M.G.; Voormolen, D.N.; Scheffer, P.G.; De Heus, R.; Van Rijn, B.B.; Bekker, M.N. Effect of Maternal Diabetes on Fetal Heart Function on Ultrasound and Fetal Echocardiography: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 57, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovsgaard, J.; Haugaard, M.; Iversen, K.K.; Hjortdal, V.E.; Bech, B.H. Cardiac Function in Offspring of Mothers with Diabetes in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1404625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.; Xu, T.; Chen, T.; Deng, X.; Kong, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy and Fetal Cardiac Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| UDCA (43) | Placebo (57) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 34.5 (4.31) | 32.6 (6.11) | 0.071 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.6 (3.98) | 29.4 (4.50) | 0.764 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.2 (12.9) | 77.9 (13.5) | 0.922 |

| Gestational age (days) | 27.9 (1.71) | 28.2 (1.75) | 0.303 |

| Ethnicity | 0.887 | ||

| -White | 42 (96.4%) | 57 (100%) | |

| -Asian | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Nulliparity | 22 (51.1%) | 22 (38.5%) | 0.487 |

| Fasting glucose at OGTT (mg/dL) | 87.1 (14.3) | 87.8 12.4) | 0.802 |

| 1 h glucose at OGTT (mg/dL) | 192.0 (27.0) | 194.0 (21.4) | 0.747 |

| 2 h glucose at OGTT (mg/dL) | 182.0 (23.0) | 185.0 (17.1) | 0.671 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.15 (0.34) | 5.22 (0.50) | 0.439 |

| Biochemical profile | |||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 236.0 (47.9) | 229.0 (37.4) | 0.503 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 70.2 (12.1) | 72.9 (17.1) | 0.375 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 122.0 (41.1) | 116.0 (35.4) | 0.518 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 216.0 (68.9) | 200.0 (49.0) | 0.221 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.61 (0.51) | 0.70 (0.74) | 0.514 |

| Ratio (s-Flt1:PLGF) | 2.7 (2.1) | 2.5 (2.3) | 0.847 |

| ALT/GOT (IU/L) | 12.6 (6.04) | 13.1 (6.38) | 0.325 |

| AST/GPT (IU/L) | 14.7 (3.35) | 15.6 5.29) | 0.711 |

| Timepoint | Variable | Mean Control | SD Control | Mean Intervention | SD Intervention | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||||

| Ao_Vmáx_(Doppler) | 77.3 | 13.5 | 71.6 | 12.8 | 0.0365 | |

| ET_(msec) | 165.0 | 13.9 | 165.0 | 27.7 | 0.95 | |

| HR | 144.0 | 12.4 | 142.0 | 10.8 | 0.409 | |

| IVCT_(msec) | 40.4 | 8.13 | 43.9 | 9.45 | 0.059 | |

| IVRT_(msec) | 51.5 | 9.59 | 55.3 | 13.3 | 0.113 | |

| LVOT_d | 4.65 | 0.682 | 4.62 | 0.611 | 0.815 | |

| MPI | 40.6 | 7.95 | 43.7 | 9.52 | 0.0846 | |

| MV_A | 50.5 | 9.61 | 48.3 | 9.7 | 0.252 | |

| MV_E | 35.7 | 8.35 | 34.6 | 6.34 | 0.449 | |

| TAPSE_(mm) | 5.86 | 1.11 | 5.78 | 1.12 | 0.723 | |

| TV_A | 52.2 | 9.88 | 51.0 | 9.77 | 0.589 | |

| TV_E | 41.0 | 10.5 | 41.4 | 10.9 | 0.856 | |

| Third Trimester | ||||||

| Ao_Vmáx_(Doppler) | 83.1 | 16.8 | 84.7 | 15.9 | 0.639 | |

| ET_(msec) | 168.0 | 15.0 | 166.0 | 15.8 | 0.616 | |

| HR | 140.0 | 14.7 | 141.0 | 11.1 | 0.677 | |

| IVCT_(msec) | 41.5 | 10.4 | 41.4 | 7.55 | 0.971 | |

| IVRT_(msec) | 57.9 | 10.5 | 59.6 | 11.7 | 0.471 | |

| LVOT_d | 6.13 | 0.801 | 6.04 | 0.777 | 0.586 | |

| MPI | 41.3 | 9.73 | 41.3 | 7.16 | 0.985 | |

| MV_A | 50.3 | 9.8 | 49.4 | 8.77 | 0.631 | |

| MV_E | 39.9 | 8.24 | 40.4 | 8.79 | 0.78 | |

| TAPSE_(mm) | 7.27 | 1.05 | 8.5 | 5.89 | 0.184 | |

| TV_A | 60.3 | 8.87 | 55.7 | 11.9 | 0.0497 | |

| TV_E | 47.7 | 10.3 | 49.7 | 13.0 | 0.405 | |

| Postpartum | ||||||

| Ao_Vmáx_(Doppler) | 101.0 | 14.2 | 103.0 | 13.7 | 0.476 | |

| ET_(msec) | 195.0 | 22.3 | 192.0 | 15.8 | 0.572 | |

| HR | 140.0 | 15.9 | 142.0 | 12.1 | 0.393 | |

| IVCT_(msec) | 44.8 | 11.0 | 45.5 | 12.1 | 0.764 | |

| IVRT_(msec) | 48.5 | 8.38 | 51.5 | 10.3 | 0.159 | |

| LVOT_d | 7.95 | 1.13 | 8.16 | 1.05 | 0.362 | |

| MPI | 44.8 | 11.1 | 45.8 | 12.1 | 0.693 | |

| MV_A | 74.1 | 15.9 | 81.4 | 19.8 | 0.0756 | |

| MV_E | 92.8 | 17.6 | 89.0 | 14.4 | 0.278 | |

| TAPSE_(mm) | 12.0 | 1.61 | 11.7 | 1.51 | 0.392 | |

| TV_A | 65.1 | 18.4 | 70.0 | 16.5 | 0.211 | |

| TV_E | 67.7 | 13.8 | 66.2 | 13.1 | 0.621 |

| Fixed Effect | Estimate | Std. Error | df | t Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 77.265 | 1.916 | 264.605 | 40.324 | <0.001 |

| Treatment 1 | −5.634 | 2.922 | 264.605 | −1.928 | 0.0549 |

| time 1 | 6.070 | 2.514 | 185.033 | 2.415 | 0.0167 |

| time 2 | 23.677 | 2.625 | 192.140 | 9.022 | <0.001 |

| Treatment 1:time 1 | 7.013 | 3.787 | 182.580 | 1.852 | 0.0657 |

| Treatment 1:time 2 | 7.971 | 3.939 | 189.228 | 2.023 | 0.0445 |

| Fixed Effect | Estimate | Std. Error | df | t Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 50.546 | 1.635 | 274.874 | 30.911 | <0.001 |

| Treatment 1 | −2.258 | 2.510 | 274.881 | −0.899 | 0.3693 |

| time 1 | −0.205 | 2.337 | 187.893 | −0.088 | 0.9300 |

| time 2 | 23.504 | 2.476 | 200.544 | 9.494 | <0.001 |

| Treatment 1:time 1 | 1.338 | 3.538 | 186.178 | 0.378 | 0.7056 |

| Treatment 1:time 2 | 9.583 | 3.709 | 197.015 | 2.583 | 0.0105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Company Calabuig, A.M.; Carnero, J.E.B.; Chatzakis, C.; Williamson, C.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Charakida, M.; De Paco Matallana, C. The Impact of Ursodeoxycholic Acid on Fetal Cardiac Function in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Study (GUARDS Trial). J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207366

Company Calabuig AM, Carnero JEB, Chatzakis C, Williamson C, Nicolaides KH, Charakida M, De Paco Matallana C. The Impact of Ursodeoxycholic Acid on Fetal Cardiac Function in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Study (GUARDS Trial). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207366

Chicago/Turabian StyleCompany Calabuig, Ana Maria, Jose Eliseo Blanco Carnero, Christos Chatzakis, Catherine Williamson, Kypros H. Nicolaides, Marietta Charakida, and Catalina De Paco Matallana. 2025. "The Impact of Ursodeoxycholic Acid on Fetal Cardiac Function in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Study (GUARDS Trial)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207366

APA StyleCompany Calabuig, A. M., Carnero, J. E. B., Chatzakis, C., Williamson, C., Nicolaides, K. H., Charakida, M., & De Paco Matallana, C. (2025). The Impact of Ursodeoxycholic Acid on Fetal Cardiac Function in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Study (GUARDS Trial). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207366