Understanding Long-Term Survival in ALS: A Cohort Study on Subject Characteristics and Prognostic Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Methods

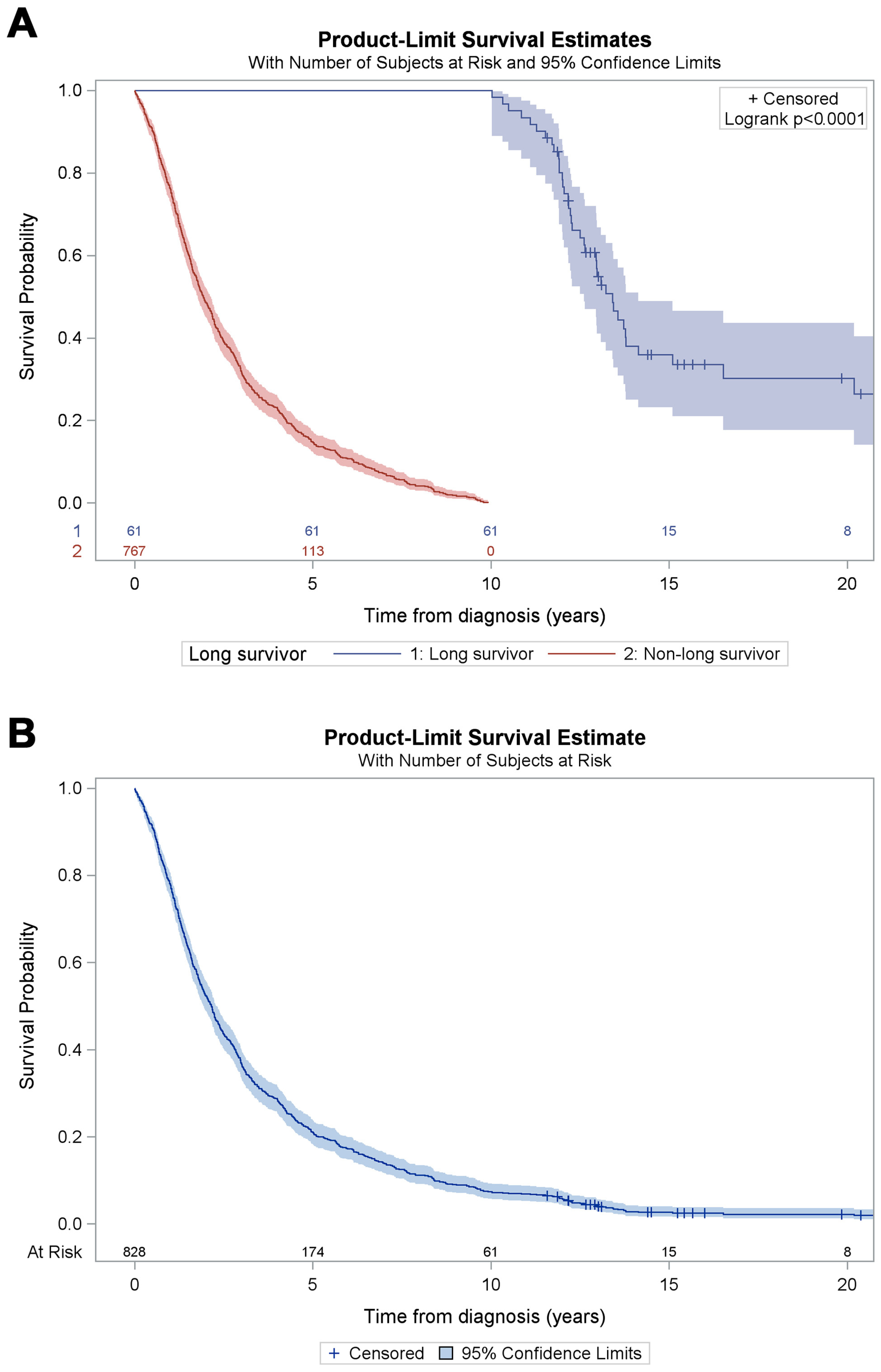

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goutman, S.A.; Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chió, A.; Savelieff, M.G.; Kiernan, M.C.; Feldman, E.L. Recent advances in the diagnosis and prognosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raggi, A.; Monasta, L.; Beghi, E.; Caso, V.; Castelpietra, G.; Mondello, S.; Giussani, G.; Logroscino, G.; Magnani, F.G.; Piccininni, M.; et al. Incidence, prevalence and disability associated with neurological disorders in Italy between 1990 and 2019: An analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 2080–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, E.; Pupillo, E.; De Feudis, A.; Enia, G.; Vitelli, E.; Beghi, E. Trends in survival of ALS from a population-based registry. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2022, 23, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agosta, F.; Spinelli, E.G.; Riva, N.; Fontana, A.; Basaia, S.; Canu, E.; Castelnovo, V.; Falzone, Y.; Carrera, P.; Comi, G.; et al. Survival prediction models in motor neuron disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019, 26, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatelli, M.; Zollino, M.; Luigetti, M.; Del Grande, A.; Lattante, S.; Marangi, G.; Monaco, M.L.; Madia, F.; Meleo, E.; Bisogni, G.; et al. Uncovering amyotrophic lateral sclerosis phenotypes: Clinical features and long-term follow-up of upper motor neuron-dominant ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2011, 12, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leighton, D.J.; Ansari, M.; Newton, J.; Parry, D.; Cleary, E.; Colville, S.; Stephenson, L.; Larraz, J.; Johnson, M.; Beswick, E.; et al. Genotype-phenotype characterisation of long survivors with motor neuron disease in Scotland. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, R.; Bury, J.J.; Appleby-Mallinder, C.; Wyles, M.; Loxley, G.; Babel, A.; Shekari, S.; Kazoka, M.; Wollff, H.; Al-Chalabi, A.; et al. Establishing mRNA and microRNA interactions driving disease heterogeneity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient survival. Brain Commun. 2023, 6, fcad331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Brayne, C.; Beghi, E.; Berg, L.H.v.D.; Chio, A.; Martin, S.; Logroscino, G.; Rooney, J. The changing picture of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Lessons from European registers. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2017, 88, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witzel, S.; Wagner, M.; Zhao, C.; Kandler, K.; Graf, E.; Berutti, R.; Oexle, K.; Brenner, D.; Winkelmann, J.; Ludolph, A.C. Fast versus slow disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-clinical and genetic factors at the edges of the survival spectrum. Neurobiol. Aging. 2022, 119, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pupillo, E.; Messina, P.; Logroscino, G.; Beghi, E.; SLALOM Group. Long-term survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A population-based study. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 75, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateen, F.J.; Carone, M.; Sorenson, E.J. Patients who survive 5 years or more with ALS in Olmsted County, 1925–2004. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2010, 81, 1144–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiò, A.; Logroscino, G.; Hardiman, O.; Swingler, R.; Mitchell, D.; Beghi, E.; Traynor, B.G. Prognostic factors in ALS: A critical review. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2009, 10, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasta, R.; De Mattei, F.; Tafaro, S.; Canosa, A.; Manera, U.; Grassano, M.; Palumbo, F.; Cabras, S.; Matteoni, E.; Di Pede, F.; et al. Changes to Average Survival of Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (1995–2018): Results From the Piemonte and Valle d’Aosta Registry. Neurology 2025, 104, e213467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czaplinski, A.; Yen, A.A.; Appel, S.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Early predictors of prolonged survival. J. Neurol. 2006, 253, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccolella, S.; Beghi, E.; Palagano, G.; Fraddosio, A.; Guerra, V.; Samarelli, V.; Lepore, V.; Simone, I.L.; Lamberti, P.; Serlenga, L.; et al. Predictors of long survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A population-based study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2008, 268, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.; Al Khleifat, A.; Meurgey, J.H.; Jones, A.; Leigh, P.N.; Bensimon, G.; Al-Chalabi, A. Stage at which riluzole treatment prolongs survival in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A retrospective analysis of data from a dose-ranging study. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n = 828) | Survival < 10 Years (n = 767) | Survival ≥ 10 Years (n = 61) | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | ||

| Follow-up duration | 2.2 | 1.1–4.4 | 1.9 | 1.0–3.6 | 12.9 | 12.0–14.5 | <0.0001 |

| Age at diagnosis | 66.3 | 58.2–73.0 | 67.2 | 59.1–73.4 | 57.2 | 48.2–63.8 | <0.0001 |

| Age at onset | 65.4 | 57.1–72.2 | 66 | 58.0–72.6 | 55.5 | 45.2–62.4 | <0.0001 |

| Diagnostic delay * (months) | 9.1 | 5.5–13.4 | 9 | 5.4–13.1 | 12.1 | 8.0–21.1 | 0.0003 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Diagnosis period | 0.4986 | ||||||

| 1998–2002 | 401 | 48.4 | 374 | 48.8 | 27 | 44.3 | |

| 2008–2012 | 427 | 51.6 | 393 | 51.2 | 34 | 55.7 | |

| Sex | 0.0024 | ||||||

| Female | 371 | 44.8 | 355 | 46.3 | 16 | 26.2 | |

| Male | 457 | 55.2 | 412 | 53.7 | 45 | 73.8 | |

| El Escorial category at diagnosis | 0.0555 | ||||||

| Definite ALS | 311 | 37.6 | 297 | 38.7 | 14 | 23 | |

| Probable ALS | 303 | 36.6 | 279 | 36.4 | 24 | 39.3 | |

| Possible ALS | 87 | 10.5 | 77 | 10 | 10 | 16.4 | |

| Suspected ALS | 127 | 15.3 | 114 | 14.9 | 13 | 21.3 | |

| Site of onset | 0.0108 | ||||||

| Bulbar/generalized | 331 | 40 | 316 | 41.2 | 15 | 24.6 | |

| Spinal | 497 | 60 | 451 | 58.8 | 46 | 75.4 | |

| PEG | 0.8174 | ||||||

| No | 318 | 62 | 285 | 61.8 | 33 | 63.5 | |

| Yes | 195 | 38 | 176 | 38.2 | 19 | 36.5 | |

| Missing | 315 | 306 | 9 | ||||

| NIV | 0.2361 | ||||||

| No | 308 | 60.6 | 281 | 61.5 | 27 | 52.9 | |

| Yes | 200 | 39.4 | 176 | 38.5 | 24 | 47.1 | |

| Missing | 320 | 310 | 10 | ||||

| Riluzole | 0.0916 | ||||||

| No | 72 | 17.1 | 62 | 16.1 | 10 | 27 | |

| Yes | 350 | 82.9 | 323 | 83.9 | 27 | 73 | |

| Missing | 406 | 382 | 24 | ||||

| Subject | Year of Onset | Sex | Site of Onset | Year of Diagnosis | Status | Survival Time from Diagnosis (Years) | Tracheostomy-Free Survival Time (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1999 | Male | Spinal | 2000 | Dead | 13.8 | 12.2 |

| 2 | 2001 | Male | Spinal | 2001 | Alive | 22.4 | 12.7 |

| 3 | 2000 | Male | Spinal | 2001 | Alive | 22.6 | 8.2 |

| 4 | 2008 | Male | Bulbar | 2009 | Dead | 11.9 | 0.9 |

| 5 | 2011 | Male | Spinal | 2012 | Dead | 12.3 | 5.1 |

| 6 | 2009 | Male | Spinal | 2009 | Alive | 14.5 | 8.2 |

| 7 | 2010 | Male | Spinal | 2011 | Dead | 13.4 | 3.3 |

| 8 | 2009 | Male | Spinal | 2009 | Dead | 12.9 | 2.7 |

| 9 | 2006 | Male | Bulbar | 2008 | Alive | 14.4 | 12.7 |

| 10 | 2008 | Male | Spinal | 2009 | Dead | 13.7 | 6.9 |

| 11 | 2006 | Male | Spinal | 2008 | Alive | 15.4 | Not available |

| Subject | Gender | Year of Onset | Site of Onset | Year of Diagnosis | Status | Genetic Test Performed | Mutation Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Male | 2009 | Bulbar | 2010 | Dead | None | |

| B | Male | 2008 | Spinal | 2010 | Dead | None | |

| C | Female | 1999 | Spinal | 2001 | Dead | None | |

| D | Female | 2009 | Spinal | 2011 | Dead | None | |

| E | Female | 2001 | Spinal | 2002 | Alive | None | |

| F | Female | 2000 | Spinal | 2004 | Alive | None | |

| G | Male | 2011 | Spinal | 2012 | Dead | None | |

| H | Male | 2010 | Spinal | 2011 | Dead | None | |

| J | Male | 2008 | Spinal | 2009 | Dead | None | |

| K | Male | 2004 | Spinal | 2009 | Alive | None | |

| I | Female | 2012 | Spinal | 2012 | Alive | None | |

| L | Male | 2008 | Spinal | 2009 | Dead | None | |

| M | Male | 2008 | Spinal | 2009 | Dead | None | |

| N | Male | 2009 | Spinal | 2009 | Dead | None | |

| O | Male | 2008 | Bulbar | 2009 | Dead | SOD1, FUS, TDP43, C9ORF72 | None |

| P | Male | 2011 | Spinal | 2012 | Dead | SOD1, FUS, TDP43, C9ORF72 | None |

| Q | Male | 2010 | Spinal | 2011 | Dead | SOD1, FUS, TDP43, C9ORF72 | None |

| R | Female | 2010 | Spinal | 2010 | Dead | SOD1, FUS, TDP43, C9ORF72 | TDP43 |

| S | Female | 2010 | Bulbar | 2011 | Dead | SOD1, FUS, TDP43, C9ORF72 | None |

| T | Female | 2010 | Spinal | 2011 | Alive | SOD1, FUS, TDP43, C9ORF72 | None |

| U | Male | 2011 | Spinal | 2012 | Alive | SOD1, FUS, TDP43, C9ORF72 | None |

| V | Female | 2011 | Spinal | 2011 | Alive | SOD1, FUS, TDP43, C9ORF72 | None |

| W | Male | 2006 | Spinal | 2008 | Alive | SOD1, FUS, TDP43, C9ORF72 | None |

| X | Female | 2007 | Bulbar | 2008 | Alive | C9ORF72 | None |

| Y | Male | 2008 | Spinal | 2009 | Dead | SOD1 | None |

| Z | Male | 2011 | Spinal | 2012 | Alive | SOD1, FUS, TDP43, C9ORF72 | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pupillo, E.; Bianchi, E.; Leone, M.A.; Corbo, M.; Filosto, M.; Padovani, A.; Risi, B.; Vedovello, M.; dell’Era, V.; Cerri, F.; et al. Understanding Long-Term Survival in ALS: A Cohort Study on Subject Characteristics and Prognostic Factors. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7351. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207351

Pupillo E, Bianchi E, Leone MA, Corbo M, Filosto M, Padovani A, Risi B, Vedovello M, dell’Era V, Cerri F, et al. Understanding Long-Term Survival in ALS: A Cohort Study on Subject Characteristics and Prognostic Factors. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7351. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207351

Chicago/Turabian StylePupillo, Elisabetta, Elisa Bianchi, Maurizio Angelo Leone, Massimo Corbo, Massimiliano Filosto, Alessandro Padovani, Barbara Risi, Marcella Vedovello, Valentina dell’Era, Federica Cerri, and et al. 2025. "Understanding Long-Term Survival in ALS: A Cohort Study on Subject Characteristics and Prognostic Factors" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7351. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207351

APA StylePupillo, E., Bianchi, E., Leone, M. A., Corbo, M., Filosto, M., Padovani, A., Risi, B., Vedovello, M., dell’Era, V., Cerri, F., Morelli, C., Diamanti, L., Ceroni, M., Falzone, Y., Rigamonti, A., & Vitelli, E. (2025). Understanding Long-Term Survival in ALS: A Cohort Study on Subject Characteristics and Prognostic Factors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7351. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207351