Quantitative Investigation of the “K-Line Edge”, a Clustered K-Line (±) Group Derived from K-Line Assessment in Patients with Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament

Abstract

1. Introduction

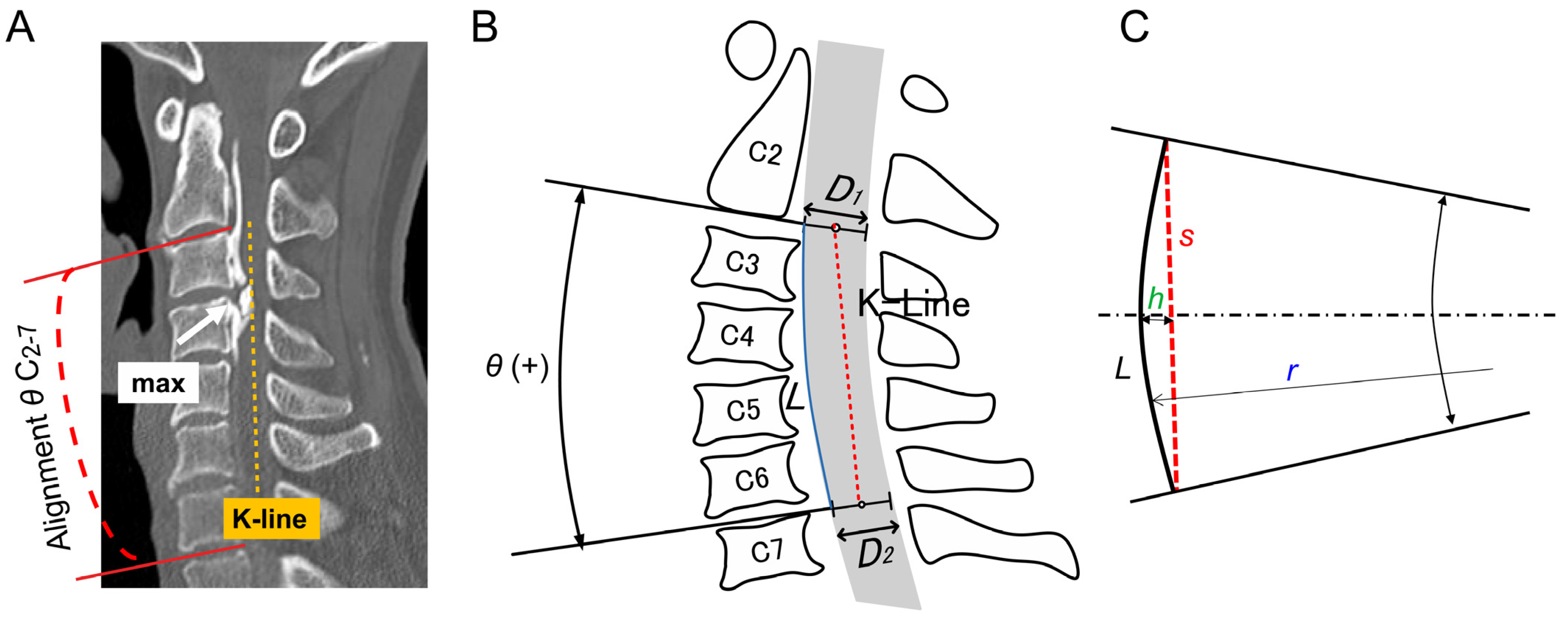

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

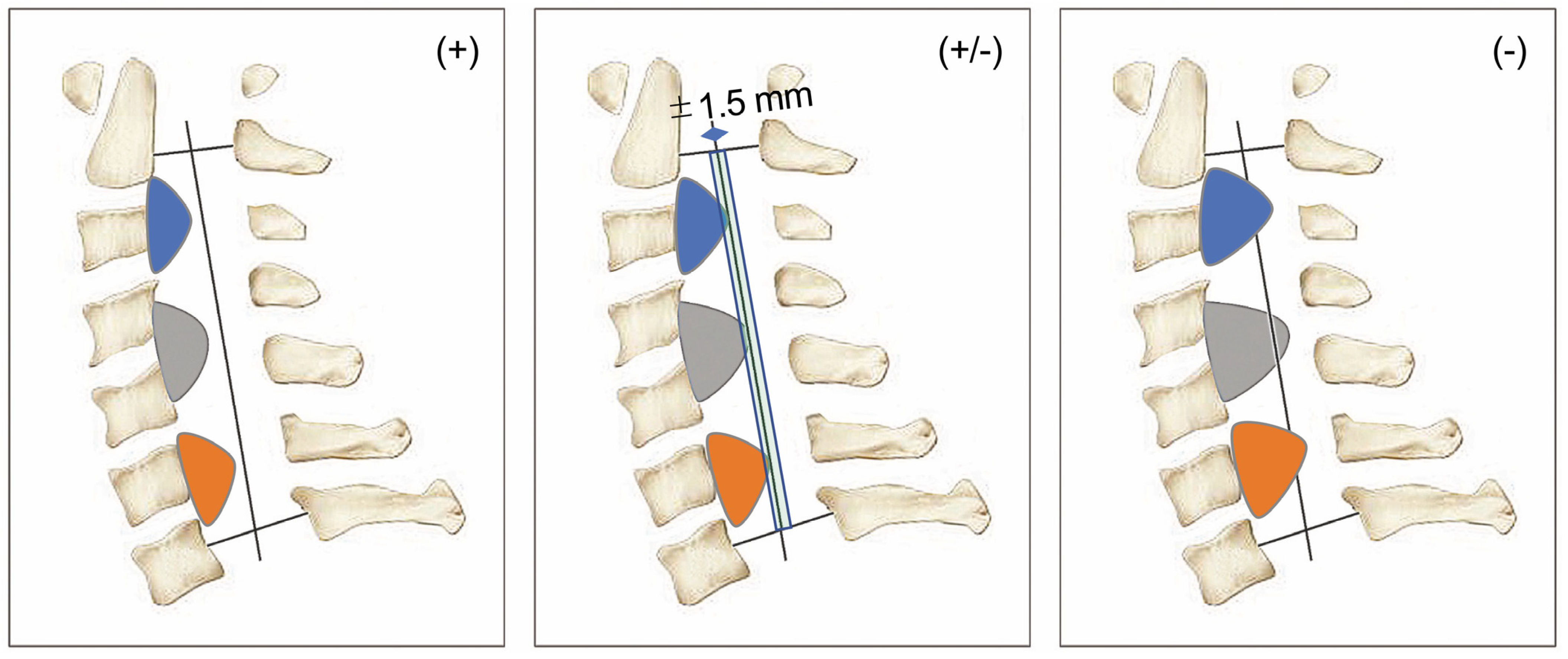

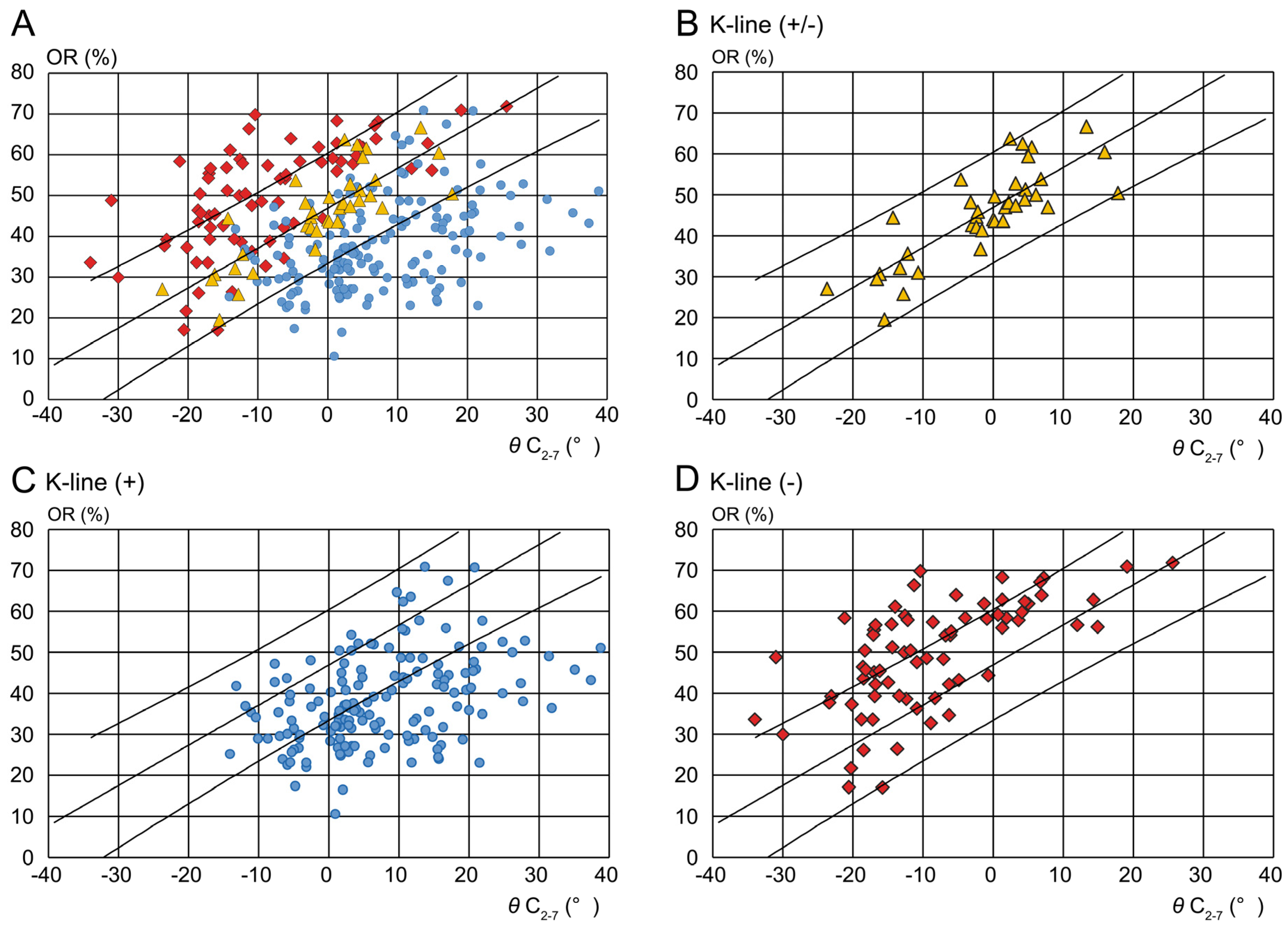

3.2. Distribution of Each K-Line Group

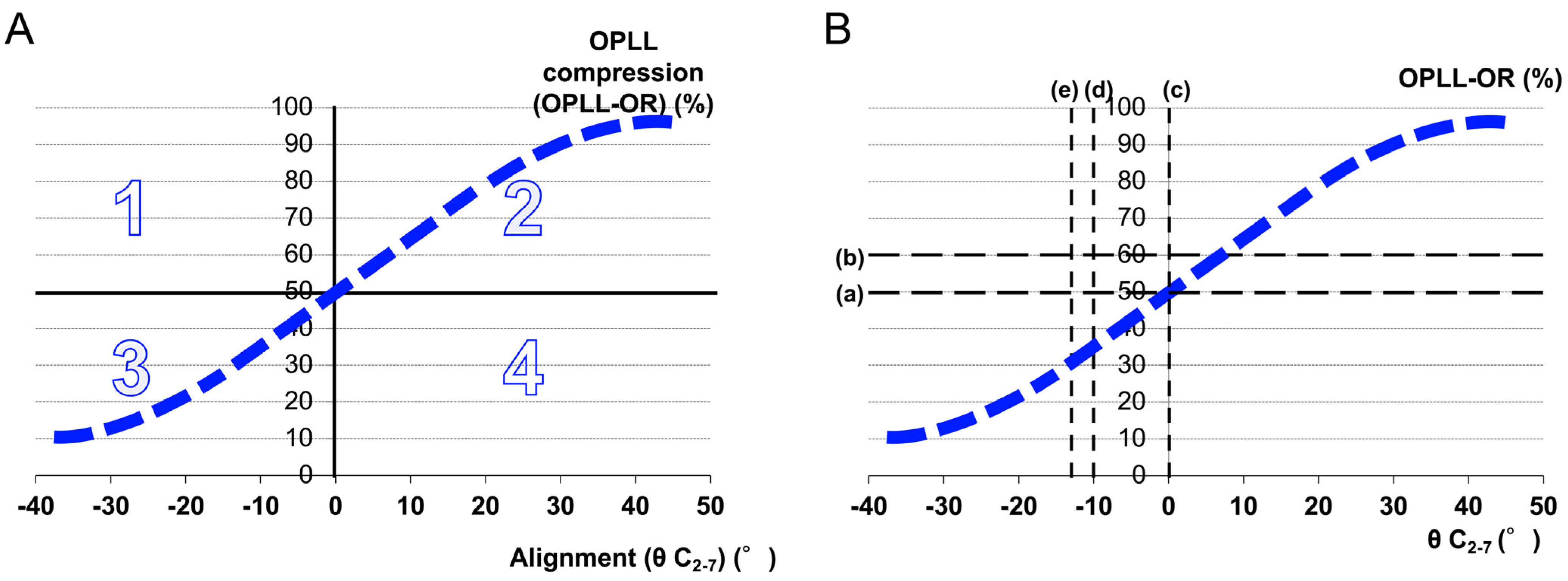

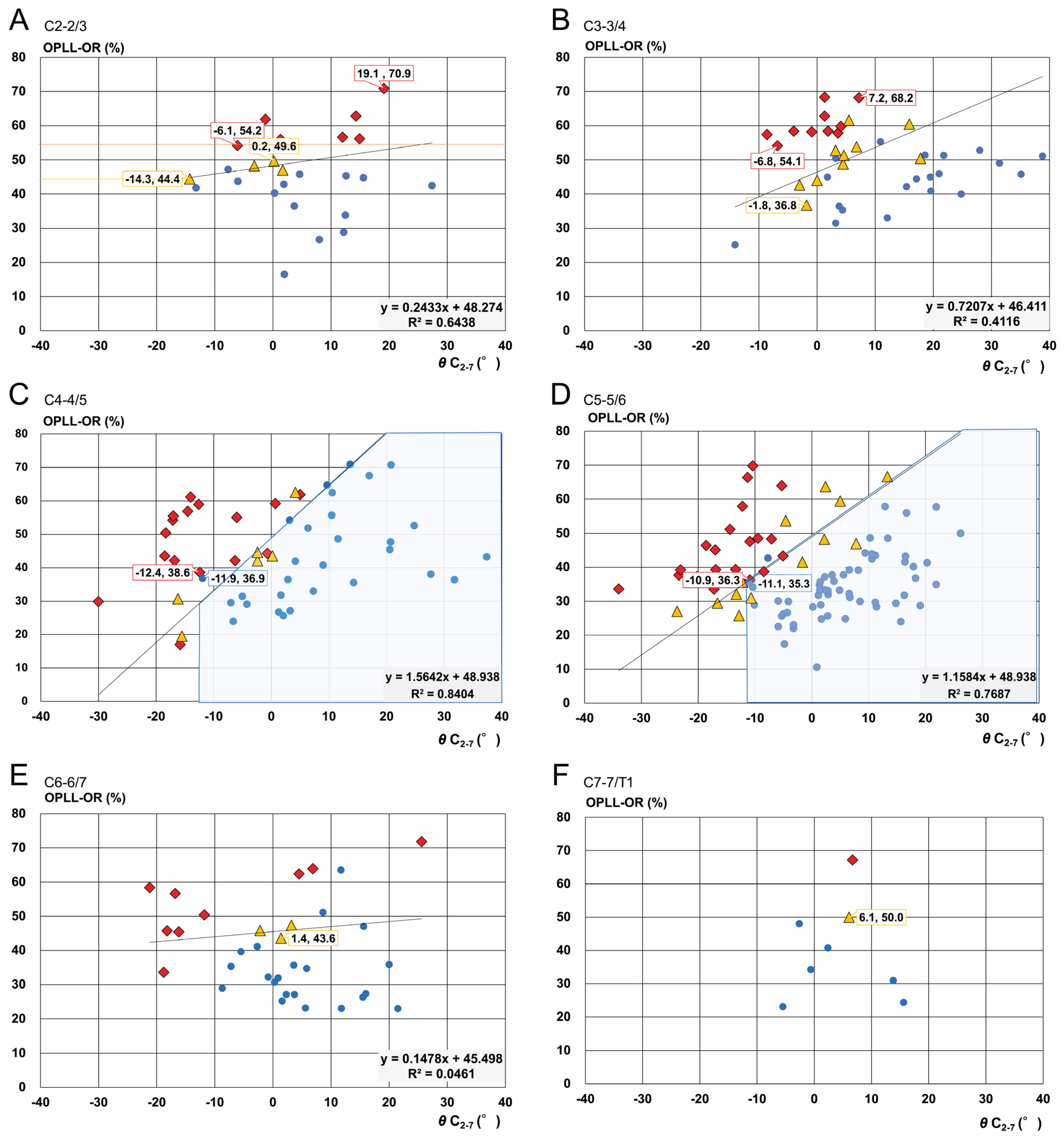

3.3. K-Line Edge Line at Each Cervical Level

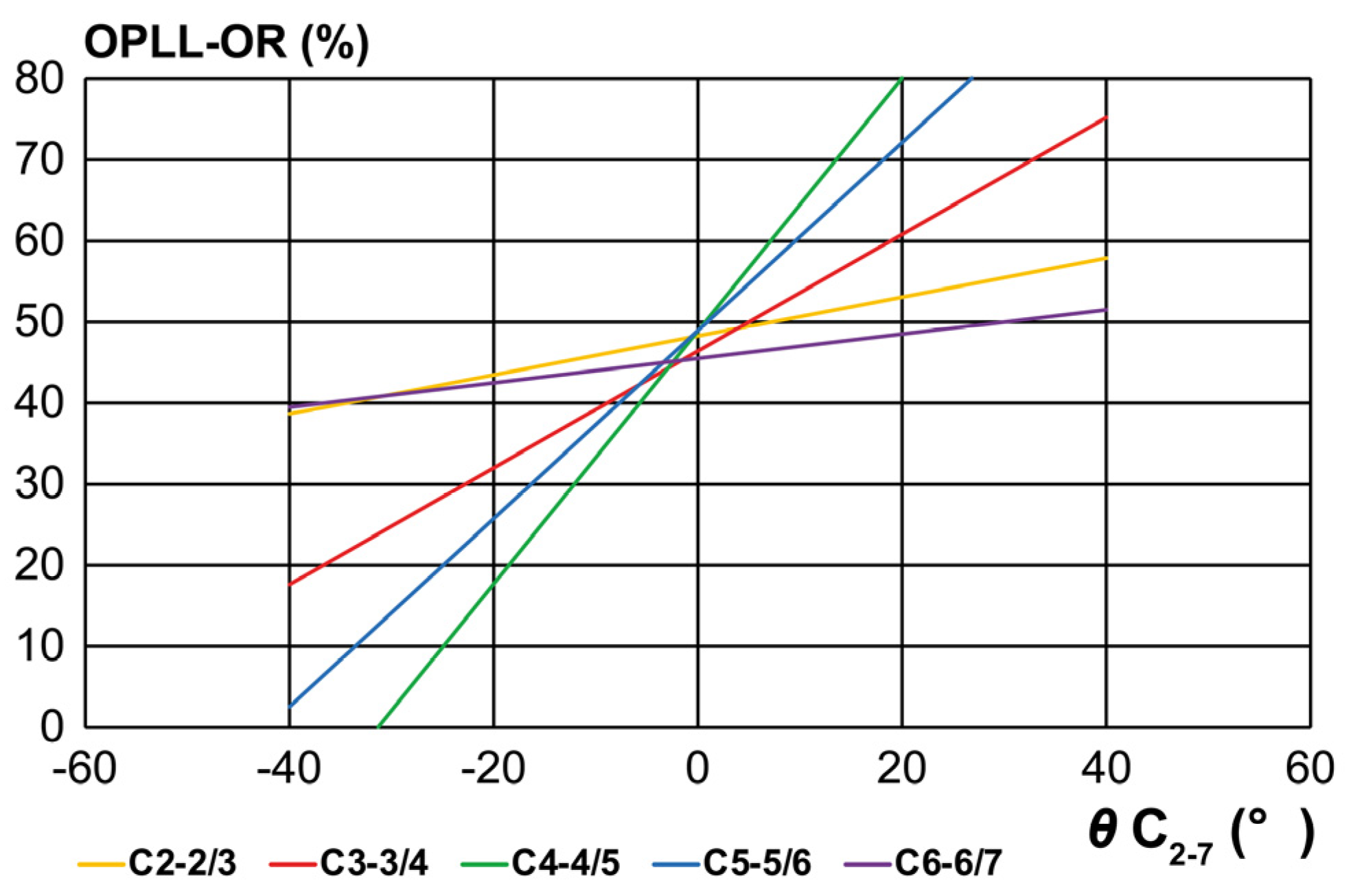

3.4. Slope of the K-Line Edge Line at Each Cervical Level

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- K-line (+) is not observed in cases with a kyphosis of −14° or less (cases with a kyphosis of 14° or more). This value is similar to previously reported value (13° kyphosis).

- (2)

- The K-line evaluation has three essential elements: OPLL thickness, cervical alignment, and cervical level at which the evaluation is performed, extending beyond the conventional binary classification of K-line (+) and (–).

- (3)

- The K-line should be considered a prognostic rather than a diagnostic tool. The K-line edge assessment introduces a quantitative aspect, which is expected to be useful as a grading scale for closely focusing on the correction angle targeting at least K-line edge (K-line (±), thereby helping to avoid excessive correction and the risk of neurological complications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | computed tomography |

| OPLL | ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament |

| OPLL-OR | OPLL-occupying ratio |

References

- Yamaura, I.; Kurosa, Y.; Matuoka, T.; Shindo, S. Anterior floating method for cervical myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1999, 359, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Lu, X.; Guo, Y.; He, Z.; Tian, H. Anterior corpectomy and fusion for severe ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine. Int. Orthop. 2009, 33, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tani, T.; Ushida, T.; Ishida, K.; Iai, H.; Noguchi, T.; Yamamoto, H. Relative safety of anterior microsurgical decompression versus laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy with a massive ossified posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine 2002, 27, 2491–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, K.; Nakajima, H.; Sato, R.; Yayama, T.; Mwaka, E.S.; Kobayashi, S.; Baba, H. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy associated with kyphosis or sagittal sigmoid alignment: Outcome after anterior or posterior decompression. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2009, 11, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, A.; Seichi, A.; Hoshino, Y.; Yamazaki, M.; Mochizuki, M.; Aiba, A.; Kato, T.; Uchida, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Nakahara, S.; et al. Perioperative complications of anterior cervical decompression with fusion in patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: A retrospective, multi-institutional study. J. Orthop. Sci. 2012, 17, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.J.; Koski, T.R.; Ganju, A.; Liu, J.C. Approach-related complications after decompression for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Neurosurg. Focus 2011, 30, E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denaro, V.; Longo, U.G.; Berton, A.; Salvatore, G.; Denaro, L. Favourable outcome of posterior decompression and stabilization in lordosis for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: The spinal cord “back shift” concept. Eur. Spine J. 2015, 24, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaki, Y.; Yamazaki, M.; Okawa, A.; Aramomi, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Koda, M.; Mochizuki, M.; Moriya, H. An analysis of factors causing poor surgical outcome in patients with cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: Anterior decompression with spinal fusion versus laminoplasty. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2007, 20, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, M.; Okuda, S.; Miyauchi, A.; Sakaura, H.; Mukai, Y.; Yonenobu, K.; Yoshikawa, H. Surgical strategy for cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: Part 1: Clinical results and limitations of laminoplasty. Spine 2007, 32, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Chiba, K.; Toyama, Y. Surgical treatment of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and its outcomes: Posterior surgery by laminoplasty. Spine 2012, 37, E303–E308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, S.E. Anterior approaches for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Which? When? How? Eur. Spine J. 2015, 24, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiyoshi, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Kawabe, J.; Endo, T.; Furuya, T.; Koda, M.; Okawa, A.; Takahashi, K.; Konishi, H. A new concept for making decisions regarding the surgical approach for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: The K-line. Spine 2008, 33, E990–E993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, T.; Miyamoto, H.; Akagi, M. Usefulness of K-line in predicting prognosis of laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, M.; Mochizuki, M.; Konishi, H.; Aiba, A.; Kadota, R.; Inada, T.; Kamiya, K.; Ota, M.; Maki, S.; Takahashi, K.; et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes between laminoplasty, posterior decompression with instrumented fusion, and anterior decompression with fusion for K-line (−) cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 2294–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, S.S.S.; Cheung, J.P.Y. Surgical decision-making for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament versus other types of degenerative cervical myelopathy: Anterior versus posterior approaches. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, J.; Maki, S.; Kamiya, K.; Furuya, T.; Inada, T.; Ota, M.; Iijima, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Yamazaki, M.; Aramomi, M.; et al. Outcome of posterior decompression with instrumented fusion surgery for K-line (−) cervical ossification of the longitudinal ligament. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 32, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuya, T.; Maki, S.; Miyamoto, T.; Okimatsu, S.; Shiga, Y.; Inage, K.; Orita, S.; Eguchi, Y.; Koda, M.; Yamazaki, M.; et al. Mid-term surgical outcome of posterior decompression with instrumented fusion in patients with K-line (−) type cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament with a 5-year minimum follow-up. Clin. Spine Surg. 2020, 33, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, F.Y.; Huo, L.S.; Zhao, Z.Q.; Sun, X.Z.; Li, F.; Ding, W.Y. Comparison of laminoplasty versus laminectomy and fusion in the treatment of multilevel cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e11542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawa, N.; Sato, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Takami, T. Review of Radiological Parameters, Imaging Characteristics, and Their Effect on Optimal Treatment Approaches and Surgical Outcomes for Cervical Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament. Neurospine 2019, 16, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Yoon, D.H.; Shin, H.C.; Kim, K.N.; Yi, S.; Shin, D.A.; Ha, Y. Surgical outcome and prognostic factors of anterior decompression and fusion for cervical compressive myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine J. 2015, 15, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Funaba, M.; Imajo, Y.; Sumi, M.; Hoshino, Y.; Okada, E.; Yamada, T.; Watanabe, K.; Hosogane, N.; Tsuji, T.; et al. Current Concepts of Cervical Spine Alignment, Sagittal Alignment, and Goals of Cervical Myelopathy Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, K.; Abumi, K.; Ito, M.; Shono, Y.; Kaneda, K.; Fujiya, M. Local kyphosis reduces surgical outcomes of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine 2003, 28, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imagama, S.; Matsuyama, Y.; Yukawa, Y.; Kawakami, N.; Kamiya, M.; Kanemura, T.; Ishiguro, N.; Nagoya Spine Group. C5 palsy after cervical laminoplasty: A multicentre study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2010, 92, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirabayashi, K.; Watanabe, K.; Wakano, K.; Suzuki, N.; Satomi, K.; Ishii, Y. Expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical spinal stenotic myelopathy. Spine 1983, 8, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruo, K.; Tachibana, T.; Inoue, S.; Arizumi, F.; Kusuyama, K.; Yoshiya, S.; Tsumura, H.; Takahashi, M.; Hayashi, K.; Nakamura, H.; et al. The impact of dynamic factors on surgical outcomes after laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2014, 21, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azuma, Y.; Kato, Y.; Taguchi, T. Etiology of cervical myelopathy induced by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: Determining the responsible level of OPLL myelopathy by correlating static compression and dynamic factors. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2010, 23, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Nakano, M.; Yasuda, T.; Seki, S.; Hori, T.; Kimura, T. Clinical impact of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament progression after cervical laminoplasty. Clin. Spine Surg. 2019, 32, E133–E139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargen, K.M.; Cox, J.B.; Hoh, D.J. Does ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament progress after laminoplasty? Radiographic and clinical evidence of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament lesion growth and the risk factors for late neurologic deterioration. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2012, 17, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seichi, A.; Chikuda, H.; Kimura, A.; Takeshita, K.; Sugita, S.; Hoshino, Y.; Nakamura, K. Intraoperative ultrasonographic evaluation of posterior decompression via laminoplasty in patients with cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: Correlation with 2-year follow-up results. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2010, 13, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batzdorf, U.; Batzdorff, A. Analysis of cervical spine curvature in patients with cervical spondylosis. Neurosurgery 1988, 22, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.D.; Janik, T.J.; Troyanovich, S.J.; Holland, B. Comparisons of lordotic cervical spine curvatures to a theoretical ideal model of the static sagittal cervical spine. Spine 1996, 21, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, T.; Sakai, K.; Hirai, T.; Yamada, T.; Inose, H.; Kato, T.; Enomoto, M.; Tomizawa, S.; Kawabata, S.; Arai, Y.; et al. Anterior decompression with fusion versus posterior decompression with fusion for massive cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament with a ≥50% canal occupying ratio: A multicenter retrospective study. Spine J. 2016, 16, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houten, J.K.; Cooper, P.R. Laminectomy and posterior cervical plating for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: Effects on cervical alignment, spinal cord compression, and neurological outcome. Neurosurgery 2003, 52, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Nadkarni, T.; Shah, A.; Rai, S.; Rangarajan, V.; Kulkarni, A. Is only stabilization the ideal treatment for ossified posterior longitudinal ligament? Report of early results with a preliminary experience in 14 patients. World Neurosurg. 2015, 84, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro, T.; Hayama, S.; Obo, T.; Nakaya, Y.; Nakano, A.; Usami, Y.; Nozawa, S.; Baba, I.; Neo, M. Gap between flexion and extension ranges of motion: A novel indicator to predict the loss of cervical lordosis after laminoplasty in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2021, 35, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, T.; Xu, B.; Chen, D. Expansive open-door laminoplasty versus laminectomy and instrumented fusion for cases with cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and straight lordosis. Eur. Spine J. 2017, 26, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koda, M.; Furuya, T.; Saito, J.; Ijima, Y.; Kitamura, M.; Ohtori, S.; Orita, S.; Inage, K.; Abe, T.; Noguchi, H.; et al. Postoperative K-line conversion from negative to positive is independently associated with a better surgical outcome after posterior decompression with instrumented fusion for K-line negative cervical ossification of the posterior ligament. Eur. Spine J. 2018, 27, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojo, Y.; Ito, M.; Abumi, K.; Kotani, Y.; Sudo, H.; Takahata, M.; Minami, A. A late neurological complication following posterior correction surgery of severe cervical kyphosis. Eur. Spine J. 2011, 20, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, S.; Nagamoto, Y.; Aono, H.; Kaito, T.; Hosono, N. Differences in the time of onset of postoperative upper limb palsy among surgical procedures: A meta-analysis. Spine J. 2016, 16, 1486–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujimoto, T.; Endo, T.; Menjo, Y.; Kanayama, M.; Oda, I.; Suda, K.; Fujita, R.; Koike, Y.; Hisada, Y.; Iwasaki, N.; et al. Exceptional conditions for favorable neurological recovery after laminoplasty in cases with cervical myelopathy caused by K-line (−) ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine 2021, 46, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Level | Cases | K-Line | Level | Alignment (θ C2–7) | OPLL-OR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (+) | (±) | (−) | Average | Range | Average | Range | |||

| C2–2/3 | 25 | 14 | 4 | 7 | C2–2/3 | 4.5 | −14.3–27.4 | 45.8 | 16.5–70.9 |

| C3–3/4 | 44 | 20 | 10 | 14 | C3–3/4 | 6.6 | −31.0–38.8 | 48.8 | 25.2–68.3 |

| C4–4/5 | 52 | 30 | 6 | 16 | C4–4/5 | 0.9 | −31.0–38.8 | 44.4 | 17.0–70.9 |

| C5–5/6 | 105 | 67 | 13 | 25 | C5–5/6 | −0.7 | −34.0–26.2 | 38.1 | 10.6–69.8 |

| C6–6/7 | 34 | 22 | 3 | 9 | C6–6/7 | 1.8 | −21.2–25.6 | 40.6 | 23.0–71.9 |

| C7–7/T1 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 1 | C7–7/T1 | 4.5 | −5.5–15.6 | 39.9 | 23.1–67.2 |

| Total | 268 | 159 | 37 | 72 | Average | 1.8° | — | 42.2% | — |

| Level | K-line (+/−): K-Line Edge Line | Coefficient | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | y = 0.98x + 46.82 | 0.98 | 0.67 |

| C2-2/3 | y = 0.24x + 48.27 | 0.24 | 0.64 |

| C3-3/4 | y = 0.72x + 46.41 | 0.72 | 0.41 |

| C4-4/5 | y = 1.56x + 48.89 | 1.56 | 0.84 |

| C5-5/6 | y = 1.16x + 48.94 | 1.16 | 0.77 |

| C6-6/7 | y = 0.15x + 45.50 | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| C7-C7/T1 | — | — | — |

| Level | K-Line Edge Line | Alignment (θ C2–7) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyphosis −10° | Straight 0° | Lordosis | ||||

| 10° | 13.5° | 20° | ||||

| Total | y = 0.98x + 46.82 | 37.0 | 46.8 | 56.6 | 60.0 | 66.4 |

| C4-4/5 | y = 1.56x + 48.89 | 33.3 | 48.9 | 64.5 | — | 80.1 |

| C5-5/6 | y = 1.16x + 48.94 | 37.3 | 49.0 | 60.5 | — | 72.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takeuchi, K.; Hosotani, K.; Shinohara, K.; Yamane, K.; Takao, S.; Nakahara, S.; Seki, A. Quantitative Investigation of the “K-Line Edge”, a Clustered K-Line (±) Group Derived from K-Line Assessment in Patients with Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207339

Takeuchi K, Hosotani K, Shinohara K, Yamane K, Takao S, Nakahara S, Seki A. Quantitative Investigation of the “K-Line Edge”, a Clustered K-Line (±) Group Derived from K-Line Assessment in Patients with Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207339

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakeuchi, Kazuhiro, Kazunori Hosotani, Kensuke Shinohara, Kentaro Yamane, Shinichiro Takao, Shinnosuke Nakahara, and Akiho Seki. 2025. "Quantitative Investigation of the “K-Line Edge”, a Clustered K-Line (±) Group Derived from K-Line Assessment in Patients with Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207339

APA StyleTakeuchi, K., Hosotani, K., Shinohara, K., Yamane, K., Takao, S., Nakahara, S., & Seki, A. (2025). Quantitative Investigation of the “K-Line Edge”, a Clustered K-Line (±) Group Derived from K-Line Assessment in Patients with Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207339