Eight Years of Follow-Up of Rituximab in Pemphigus Vulgaris and Foliaceus at a Single Center: Assessing Efficacy and Safety in Light of Several Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Characteristics

2.2. Characteristics of Patients’ Treatment Before Rituximab Administration

2.3. Disease Severity at the Time of Rituximab Administration

2.4. Body Mass Index at the Time of Rituximab Administration

2.5. Rituximab Administration in the Period of COVID-19 (Between January 2020 and December 2022)

2.6. Treatment Protocol

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

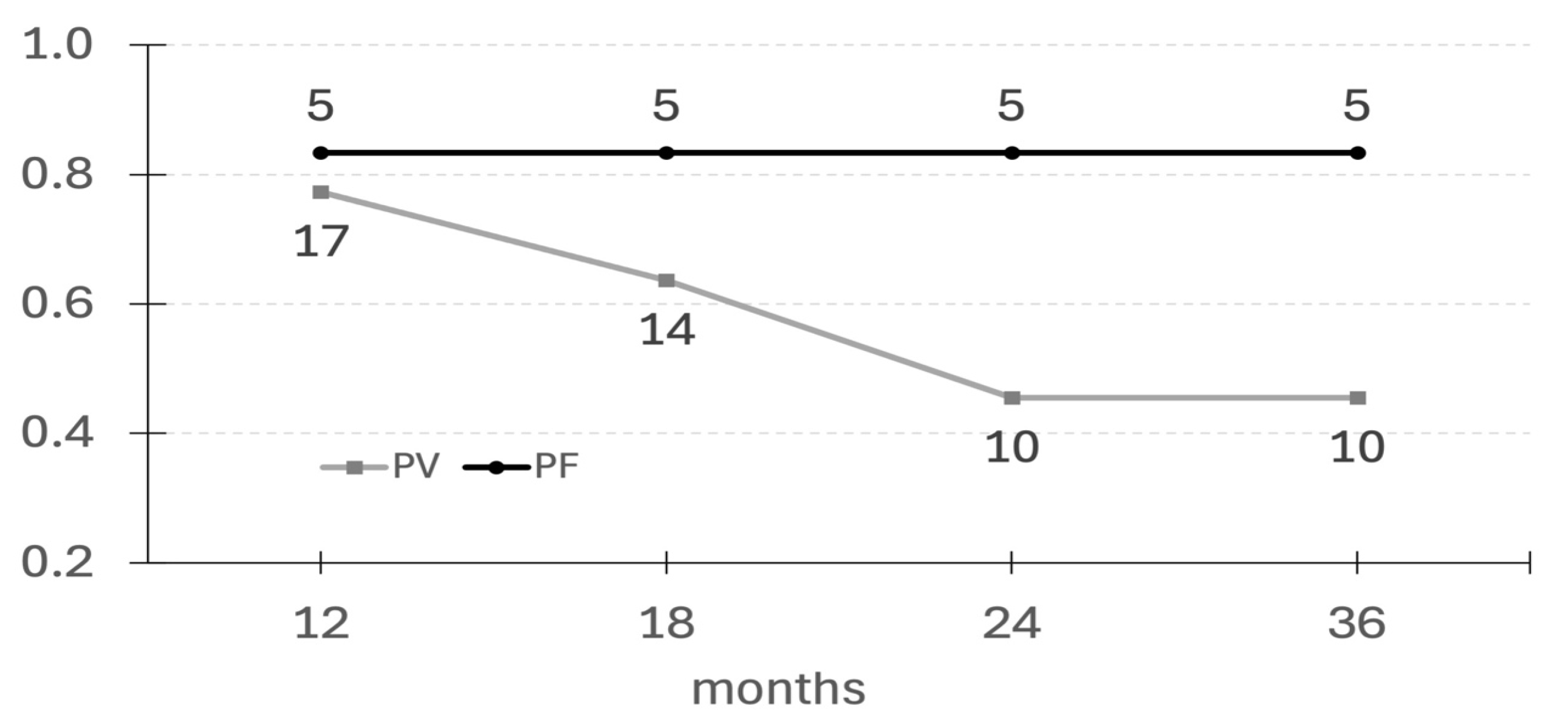

3.1. The Efficacy of a Single Cycle of Rituximab

3.2. Relapses After Single Cycle of Rituximab

3.3. Association Between Achieving Long-Term cCR and Gender, Age, PDAI, BMI, and Disease Duration Prior to Rituximab Administration

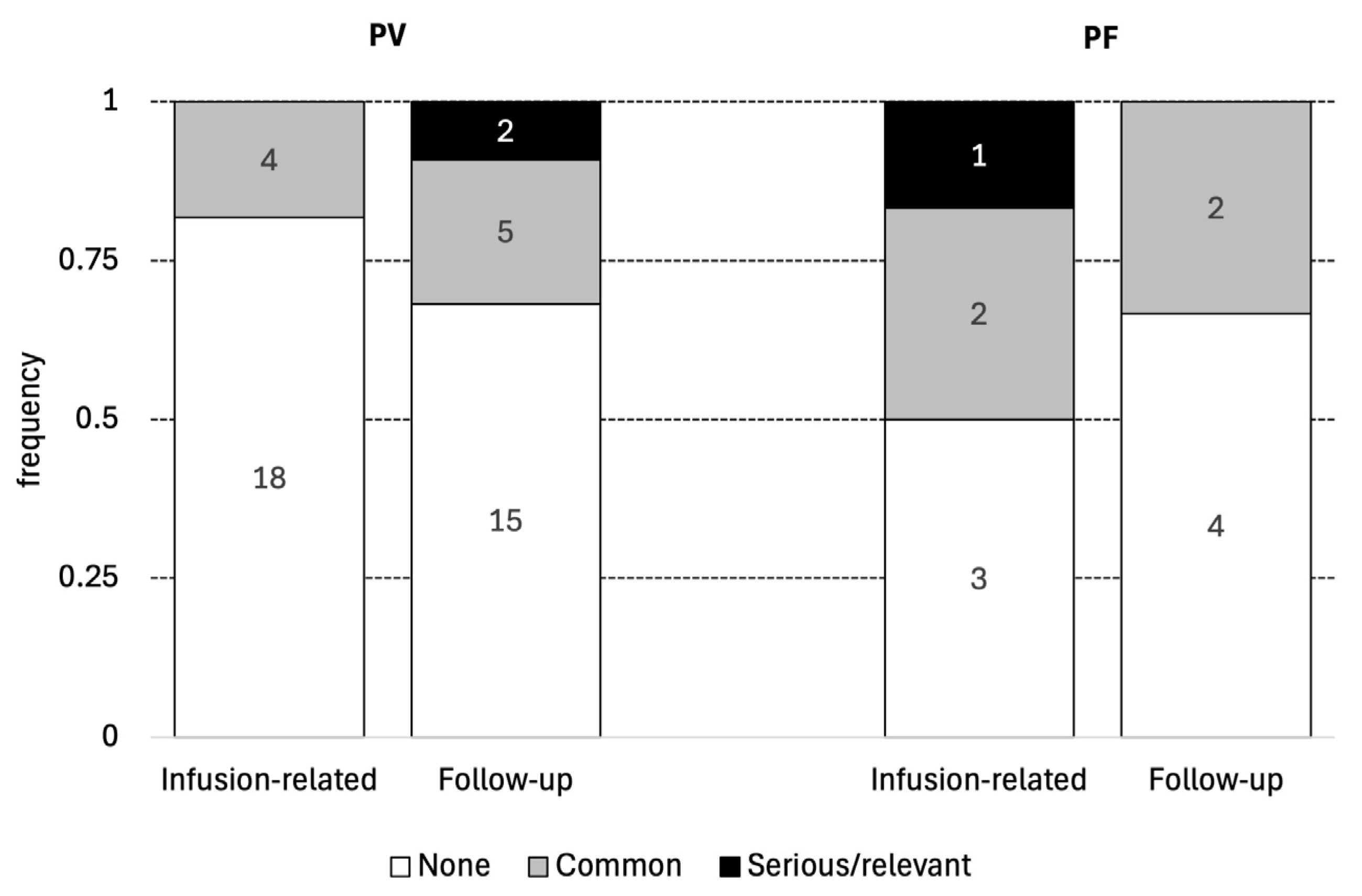

3.4. Adverse Effects Associated with Rituximab (Depicted in Table 2 and Figure 2)

3.5. Outcomes in Patients Treated with Rituximab During the COVID-19 Pandemic

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The current study has proven the high effectiveness and safety of one cycle of rituximab, especially in PF, in long-term follow-up. Therefore, rituximab may be recommended as a first-line treatment in PF; however, further studies on uniform, well-defined groups of patients are needed to support our observations.

- If patients remain in cCR for at least 36 months, they appear to have a good chance of maintaining long-term cCR and perhaps even a cure.

- Rituximab has been proven to be very safe and effective during the COVID-19 pandemic, which means that this drug may be a better therapeutic option than other immunosuppressive drugs in similar circumstances.

- Factors such as age, gender, BMI, the PDAI, and the duration of pemphigus prior to rituximab administration do not appear to influence the achievement of long-term cCR.

- A direct comparison of remission rates between our study and prior studies is difficult to perform because of different treatment protocols and conditions.

- Further prospective multicenter studies containing patients on uniform therapeutic protocols are required for a more real assessment of outcomes after rituximab therapy in pemphigus.

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PV | Pemphigus vulgaris |

| PF | Pemphigus foliaceus |

| cCR | Complete clinical remission |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| DIF | Direct immunofluorescence |

| IIF | Indirect immunofluorescence |

| PDAI | Pemphigus Disease Activity Index |

| COVID-19 | Infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 |

References

- Murrell, D.F.; Peña, S.; Joly, P.; Marinovic, B.; Hashimoto, T.; Diaz, L.A.; Sinha, A.A.; Payne, A.S.; Daneshpazhooh, M.; Eming, R.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Pemphigus: Recommendations of an International Panel of Experts. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 575–585.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, P.; Mouquet, H.; Roujeau, J.-C.; D’Incan, M.; Gilbert, D.; Jacquot, S.; Gougeon, M.-L.; Bedane, C.; Muller, R.; Dreno, B.; et al. A Single Cycle of Rituximab for the Treatment of Severe Pemphigus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianchini, G.; Corona, R.; Frezzolini, A.; Ruffelli, M.; Didona, B.; Puddu, P. Treatment of Severe Pemphigus with Rituximab: Report of 12 Cases and a Review of the Literature. Arch. Dermatol. 2007, 143, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.R.; Spigelman, Z.; Cavacini, L.A.; Posner, M.R. Treatment of Pemphigus Vulgaris with Rituximab and Intravenous Immune Globulin. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbach, M.; Murrell, D.F.; Bystryn, J.-C.; Dulay, S.; Dick, S.; Fakharzadeh, S.; Hall, R.; Korman, N.J.; Lin, J.; Okawa, J.; et al. Reliability and Convergent Validity of Two Outcome Instruments for Pemphigus. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 2404–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi (Version 2.6) [Computer Software]. 2025. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Hertl, M.; Jedlickova, H.; Karpati, S.; Marinovic, B.; Uzun, S.; Yayli, S.; Mimouni, D.; Borradori, L.; Feliciani, C.; Ioannides, D.; et al. Pemphigus. S2 Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment—Guided by the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) in Cooperation with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinska-Bienias, A.; Jakubowska, B.; Kowalewski, C.; Murrell, D.F.; Wozniak, K. Measuring of Quality of Life in Autoimmune Blistering Disorders in Poland. Validation of Disease—Specific Autoimmune Bullous Disease Quality of Life (ABQOL) and the Treatment Autoimmune Bullous Disease Quality of Life (TABQOL) Questionnaires. Adv. Med. Sci. 2017, 62, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, A.J.; Tsuruta, D.; Vinay, K.; Koga, H.; Ishii, N.; Dainichi, T.; Hashimoto, T. Efficacy and Safety of Rituximab Treatment in Indian Pemphigus Patients. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2013, 27, e17–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.; Hunzelmann, N.; Zillikens, D.; Brocker, E.-B.; Goebeler, M. Rituximab in Refractory Autoimmune Bullous Diseases. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2006, 31, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, P.; Horvath, B.; Patsatsi, A.; Uzun, S.; Bech, R.; Beissert, S.; Bergman, R.; Bernard, P.; Borradori, L.; Caproni, M.; et al. Updated S2K Guidelines on the Management of Pemphigus Vulgaris and Foliaceus Initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 1900–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, P.; Maho-Vaillant, M.; Prost-Squarcioni, C.; Hebert, V.; Houivet, E.; Calbo, S.; Caillot, F.; Golinski, M.L.; Labeille, B.; Picard-Dahan, C.; et al. First-Line Rituximab Combined with Short-Term Prednisone versus Prednisone Alone for the Treatment of Pemphigus (Ritux 3): A Prospective, Multicentre, Parallel-Group, Open-Label Randomised Trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2031–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozca, B.C.; Bilgiç, A.; Uzun, S. Long-Term Experience with Rituximab Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Moderate-to-Severe Pemphigus. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 2102–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, C.J.; Wang, S.; Tovanabutra, N.; Tsai, D.E.; Werth, V.P.; Payne, A.S. Factors Associated with Complete Remission After Rituximab Therapy for Pemphigus. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 1404–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosrati, A.; Hodak, E.; Mimouni, T.; Oren-Shabtai, M.; Levi, A.; Leshem, Y.A.; Mimouni, D. Treatment of Pemphigus with Rituximab: Real-Life Experience in a Cohort of 117 Patients in Israel. Dermatology 2021, 237, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.J.; Mistry, D.; Shah, S.R. Long-term Efficacy and Safety Analysis of Single Cycle of Biosimilar Rituximab in Pemphigus: A Retrospective Study of 76 Patients from India. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Álvarez, I.; Riquelme-Mc Loughlin, C.; Curto-Barredo, L.; Iranzo, P.; García-Díez, I.; España, A. Rituximab Treatment of Pemphigus Foliaceus: A Retrospective Study of 12 Patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sena Nogueira Maehara, L.; Huizinga, J.; Jonkman, M.F. Rituximab Therapy in Pemphigus Foliaceus: Report of 12 Cases and Review of Recent Literature. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 1420–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardon, L.; Tsai, K.J.; Propert, K.J.; Fett, N.; Stanley, J.R.; Werth, V.P.; Tsai, D.E.; Payne, A.S. Adjuvant Rituximab Therapy of Pemphigus: A Single-Center Experience with 31 Patients. Arch. Dermatol. 2012, 148, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, A.; Mimouni, T.; Hodak, E.; Gdalevich, M.; Oren-Shabtai, M.; Levi, A.; Mimouni, D.; Leshem, Y.A. Early Rituximab Treatment Is Associated with Increased and Sustained Remission in Pemphigus Patients: A Retrospective Cohort of 99 Patients. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedbirt, B.; Maho-Vaillant, M.; Houivet, E.; Mignard, C.; Golinski, M.-L.; Calbo, S.; Prost-Squarcioni, C.; Labeille, B.; Picard-Dahan, C.; Chaby, G.; et al. Sustained Remission Without Corticosteroids Among Patients with Pemphigus Who Had Rituximab as First-Line Therapy: Follow-Up of the Ritux 3 Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Bhari, N.; Gupta, S.; Sahni, K.; Khanna, N.; Ramam, M.; Sethuraman, G. Clinical Efficacy of Rituximab in the Treatment of Pemphigus: A Retrospective Study. Indian. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2016, 82, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y. Efficacy of Rituximab for Pemphigus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Different Regimens. Acta Derm. Venerol. 2015, 95, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miše, J.; Jukić, I.L.; Marinović, B. Rituximab-Progress but Still Not a Final Resolution for Pemphigus Patients: Clinical Report from a Single Center Study. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 884931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardon, L.; Payne, A.S. Inhibitory Human Antichimeric Antibodies to Rituximab in a Patient with Pemphigus. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 800–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunardon, L.; Payne, A.S. Rituximab for Autoimmune Blistering Diseases: Recent Studies, New Insights. Ital. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012, 147, 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, S.; Goto, H.; Tanoshima, R.; Kato, H.; Takahashi, H.; Sekiguchi, O.; Kai, S. Serum Sickness with an Elevated Level of Human Anti-Chimeric Antibody Following Treatment with Rituximab in a Child with Chronic Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura. Int. J. Hematol. 2009, 89, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, E.; Hennig, K.; Mengede, C.; Zillikens, D.; Kromminga, A. Immunogenicity of Rituximab in Patients with Severe Pemphigus. Clin. Immunol. 2009, 132, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pijpe, J.; Van Imhoff, G.W.; Spijkervet, F.K.L.; Roodenburg, J.L.N.; Wolbink, G.J.; Mansour, K.; Vissink, A.; Kallenberg, C.G.M.; Bootsma, H. Rituximab Treatment in Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome: An Open-label Phase II Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 2740–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakou, M.; Katsikas, G.; Sidiropoulos, P.; Bertsias, G.; Papadimitraki, E.; Raptopoulou, A.; Koutala, H.; Papadaki, H.A.; Kritikos, H.; Boumpas, D.T. Rituximab Therapy Reduces Activated B Cells in Both the Peripheral Blood and Bone Marrow of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: Depletion of Memory B Cells Correlates with Clinical Response. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, R131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.E.; Lim, J.M.; Kim, S. Adjuvant Rituximab Treatment for Pemphigus: A Retrospective Study of 45 Patients at a Single Center with Long-term Follow Up. J. Dermatol. 2017, 44, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mignard, C.; Maho-Vaillant, M.; Golinski, M.-L.; Balayé, P.; Prost-Squarcioni, C.; Houivet, E.; Calbo, S.B.; Labeille, B.; Picard-Dahan, C.; Konstantinou, M.P.; et al. Factors Associated with Short-Term Relapse in Patients with Pemphigus Who Receive Rituximab as First-Line Therapy: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020, 156, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryanian, Z.; Riyaz, I.Z.; Balighi, K.; Ahmadzade, A.; Mahmoudi, H.R.; Azizpour, A.; Hatami, P. Combination Therapy for Management of Pemphigus Patients with Unexpected Therapeutic Response to Rituximab: A Report of Five Cases. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Deng, S.; Luo, Y.; Deng, L. Efficacy of Rituximab in the Treatment of Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Meta-Analysis. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2024, 30, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagami, J.; Kurihara, Y.; Funakoshi, T.; Saito, Y.; Tanaka, R.; Takahashi, H.; Ujiie, H.; Iwata, H.; Hirai, Y.; Iwatsuki, K.; et al. Rituximab Therapy for Intractable Pemphigus: A Multicenter, Open-label, Single-arm, Prospective Study of 20 Japanese Patients. J. Dermatol. 2023, 50, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, W.; Ni, Z.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.; Ou, C.; He, J.; Liu, L.; Shan, H.; Lei, C.; Hui, D.S.C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyzaee, A.M.; Rahmatpour Rokni, G.; Patil, A.; Goldust, M. Rituximab as the Treatment of Pemphigus Vulgaris in the COVID-19 Pandemic Era: A Narrative Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e14405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakolpour, S.; Aryanian, Z.; Seirafianpour, F.; Dodangeh, M.; Etesami, I.; Daneshpazhooh, M.; Balighi, K.; Mahmoudi, H.; Goodarzi, A. A Systematic Review on Efficacy, Safety, and Treatment-Durability of Low-Dose Rituximab for the Treatment of Pemphigus: Special Focus on COVID-19 Pandemic Concerns. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2021, 43, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diagnosis | PV | PF |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 22 | 6 |

| Age, years | 51.5 (30–68) | 54.0 (40–67) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 13 (59.1%) | 4 (67%) |

| Male | 9 (40.9%) | 2 (33%) |

| Disease duration before rituximab (months) | 28.0 (3–181) | 60.0 (7–108) |

| PDAI at rituximab administration | 15.9 (2–66) | 22.5 (8–39) |

| BMI at rituximab administration | 31.4 (19.1–36.9) | 28.8 (21.1–34.6) |

| Rituximab administration During COVID-19 pandemic | 13 | 4 |

| Patients | PV | PF |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 22 | 6 |

| Time to remission (months) | 1.75 (0–8) | 5.5 (1–9) |

| Duration of remission lasting at least 12 months | 17 (77.3%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| 18 months | 14 (63.6%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| 24 months | 10 (45.5%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| 36 months | 10 (45.5%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| Adverse effects | ||

| Infusion-related | ||

| Common | 4 (18.2%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Serious/relevant | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Follow-up | ||

| Minor | 5 (22.7%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Relevant | 2 (9.1%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| PV | PV + PF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Gender | 0.69 | 0.12–3.78 | 0.67 | 0.909 | 0.39–2.14 | 0.83 |

| BMI > 25 | 0.39 | 0.05–2.77 | 0.350 | 0.44 | 0.07–2.80 | 0.38 |

| Duration of disease | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.75 |

| Age at Rtx therapy | 0.97 | 0.90–1.04 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.91–1.04 | 0.49 |

| PDAI > 35 | 1.78 | 0.13–23.5 | 0.66 | 2.00 | 0.27–14.59 | 0.49 |

| PV | PV + PF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Gender | 0.67 | 0.06–7.79 | 0.761 | 0.94 | 0.10–8.42 | 0.953 |

| BMI > 25 | 4.28 | 0.26–70.25 | 0.309 | 6.09 | 0.43–85.99 | 0.181 |

| Duration of disease | 1.01 | 0.98–1.05 | 0.383 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.03 | 0.534 |

| Age at Rtx therapy | 0.91 | 0.80–1.03 | 0.130 | 0.91 | 0.81–1.02 | 0.093 |

| PDAI > 35 | 0.50 | 0.01–13.72 | 0.681 | 0.46 | 0.03–7.87 | 0.595 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szymanski, K.; Kowalewski, C.; Walecka, I.; Wozniak, K. Eight Years of Follow-Up of Rituximab in Pemphigus Vulgaris and Foliaceus at a Single Center: Assessing Efficacy and Safety in Light of Several Factors. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7318. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207318

Szymanski K, Kowalewski C, Walecka I, Wozniak K. Eight Years of Follow-Up of Rituximab in Pemphigus Vulgaris and Foliaceus at a Single Center: Assessing Efficacy and Safety in Light of Several Factors. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7318. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207318

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzymanski, Konrad, Cezary Kowalewski, Irena Walecka, and Katarzyna Wozniak. 2025. "Eight Years of Follow-Up of Rituximab in Pemphigus Vulgaris and Foliaceus at a Single Center: Assessing Efficacy and Safety in Light of Several Factors" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7318. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207318

APA StyleSzymanski, K., Kowalewski, C., Walecka, I., & Wozniak, K. (2025). Eight Years of Follow-Up of Rituximab in Pemphigus Vulgaris and Foliaceus at a Single Center: Assessing Efficacy and Safety in Light of Several Factors. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7318. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207318