The Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Short-Term Health Outcomes of Delirium in Patients Admitted to a Nephrology Ward in Eastern Europe: An Observational Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

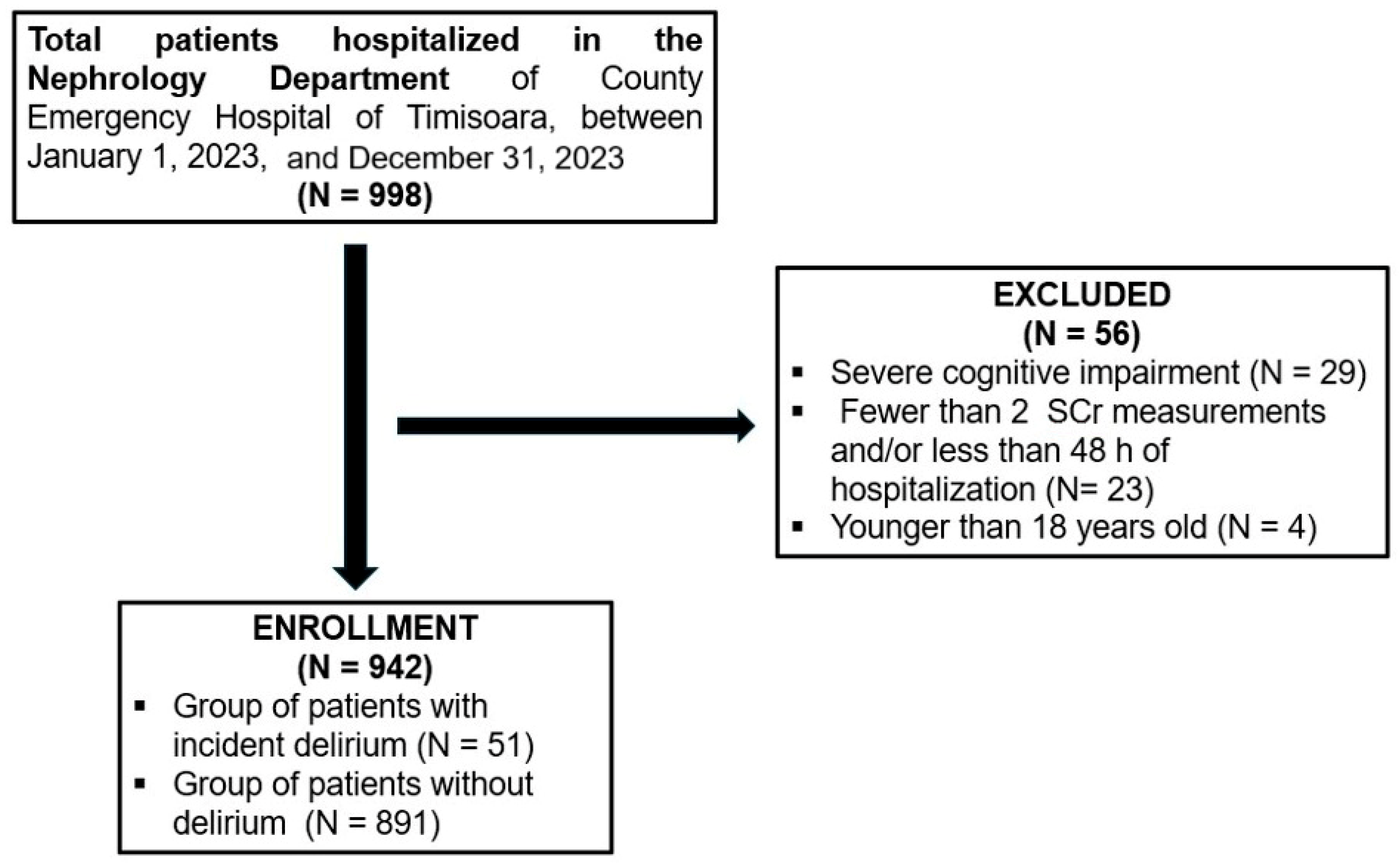

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Variables

3. Outcomes

Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Patients

4.2. Predictors of Delirium

4.3. Outcomes of Patients with Delirium

5. Discussion

5.1. Prevalence of Delirium

5.2. Risk Factors Associated with Delirium

5.3. Outcomes Associated with Delirium

5.4. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; (DSM-5); American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, F.; Tu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhan, L.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y.; Xie, C.; Chen, Y. Delirium is a Potential Predictor of Unfavorable Long-term Functional Outcomes in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Prospective Observational Study. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 4019–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.E.; Mart, M.F.; Cunningham, C.; Shehabi, Y.; Girard, T.D.; MacLullich, A.M.J.; Slooter, A.J.C.; Ely, E.W. Delirium. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 90, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, S.K.; Westendorp, R.G.; Saczynski, J.S. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014, 383, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efraim, N.T.; Zikrin, E.; Shacham, D.; Katz, D.; Makulin, E.; Barski, L.; Zeller, L.; Bartal, C.; Freud, T.; Lebedinski, S.; et al. Delirium in Internal Medicine Departments in a Tertiary Hospital in Israel: Occurrence, Detection Rates, Risk Factors, and Outcomes. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 581069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salluh, J.I.; Wang, H.; Schneider, E.B.; Nagaraja, N.; Yenokyan, G.; Damluji, A.; Serafim, R.B.; Stevens, R.D. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015, 350, h2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, R.; McKenzie, C.A.; Taylor, D.; Camporota, L.; Ostermann, M. Acute kidney injury as a risk factor of hyperactive delirium: A case control study. J. Crit. Care 2020, 55, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, M.; Schürch, R.; Boettger, S.; Garcia Nuñez, D.; Schwarz, U.; Bettex, D.; Jenewein, J.; Bogdanovic, J.; Staehli, M.L.; Spirig, R.; et al. A hospital-wide evaluation of delirium prevalence and outcomes in acute care patients—A cohort study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung Thein, M.Z.; Pereira, J.V.; Nitchingham, A.; Caplan, G.A. A call to action for delirium research: Meta-analysis and regression of delirium associated mortality. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Huraizi, A.R.; Al-Maqbali, J.S.; Al Farsi, R.S.; Al Zeedy, K.; Al-Saadi, T.; Al-Hamadani, N.; Al Alawi, A.M. Delirium and Its Association with Short- and Long-Term Health Outcomes in Medically Admitted Patients: A Prospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipser, C.M.; Deuel, J.; Ernst, J.; Schubert, M.; Weller, M.; von Känel, R.; Boettger, S. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in neurology: A prospective cohort study of 1487 patients. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 3065–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildenbrand, F.F.; Murray, F.R.; von Känel, R.; Deibel, A.R.; Schreiner, P.; Ernst, J.; Zipser, C.M.; Böettger, S. Predisposing and precipitating risk factors for delirium in gastroenterology and hepatology: Subgroup analysis of 718 patients from a hospital-wide prospective cohort study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1004407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipser, C.M.; Hildenbrand, F.F.; Haubner, B.; Deuel, J.; Ernst, J.; Petry, H.; Schubert, M.; Jordan, K.D.; von Känel, R.; Boettger, S. Predisposing and Precipitating Risk Factors for Delirium in Elderly Patients Admitted to a Cardiology Ward: An Observational Cohort Study in 1,042 Patients. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 686665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.J.; Davis, D.H.J.; Stephan, B.C.M.; Robinson, L.; Brayne, C.; Barnes, L.E.; Taylor, J.P.; Parker, S.G.; Allan, L.M. Recurrent delirium over 12 months predicts dementia: Results of the Delirium and Cognitive Impact in Dementia (DECIDE) study. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, D.L.; Inouye, S.K. The importance of delirium: Economic and societal costs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59 (Suppl. S2), S241–S243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzullo, L.; Streatfeild, J.; Hickson, J.; Teodorczuk, A.; Agar, M.R.; Caplan, G.A. Economic impact of delirium in Australia: A cost of illness study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Farsi, R.S.; Al Alawi, A.M.; Al Huraizi, A.R.; Al-Saadi, T.; Al-Hamadani, N.; Al Zeedy, K.; Al-Maqbali, J.S. Delirium in Medically Hospitalized Patients: Prevalence, Recognition and Risk Factors: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, E.A.; Holmes, J. Delirium within the emergency care setting, occurrence and detection: A systematic review. Emerg. Med. J. 2013, 30, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfold, R.S.; Squires, C.; Angus, A.; Shenkin, S.D.; Ibitoye, T.; Tieges, Z.; Neufeld, K.J.; Avelino-Silva, T.J.; Davis, D.; Anand, A.; et al. Delirium detection tools show varying completion rates and positive score rates when used at scale in routine practice in general hospital settings: A systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 1508–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geriatric Medicine Research Collaborative. Delirium is prevalent in older hospital inpatients and associated with adverse outcomes: Results of a prospective multi-centre study on World Delirium Awareness Day. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ros, P.; Plaza-Ortega, N.; Martínez-Arnau, F.M. Mortality Risk Following Delirium in Older Inpatients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2025, 22, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotfis, K.; Ślozowska, J.; Listewnik, M.; Szylińska, A.; Rotter, I. The Impact of Acute Kidney Injury in the Perioperative Period on the Incidence of Postoperative Delirium in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting-Observational Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniar, H.S.; Lindman, B.R.; Escallier, K.; Avidan, M.; Novak, E.; Melby, S.J.; Damiano, M.S.; Lasala, J.; Quader, N.; Rao, R.S.; et al. Delirium after surgical and transcatheter aortic valve replacement is associated with increased mortality. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016, 151, 815–823.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, E.D.; Fissell, W.H.; Tripp, C.M.; Blume, J.D.; Wilson, M.D.; Clark, A.J.; Vincz, A.J.; Ely, E.W.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Girard, T.D. Acute Kidney Injury as a Risk Factor for Delirium and Coma during Critical Illness. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui-Furukori, N.; Tarakita, N.; Uematsu, W.; Saito, H.; Nakamura, K.; Ohyama, C.; Sugawara, N. Delirium in hemodialysis predicts mortality: A single-center, long-term observational study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 13, 3011–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, Y.; Shioji, S.; Tanaka, H.; Kondo, I.; Sakamoto, E.; Suzuki, M.; Katagiri, D.; Tada, M.; Hinoshita, F. Delirium is independently associated with early mortality in elderly patients starting hemodialysis. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2020, 24, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KDIGO Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2012, 2, S1–S138. [Google Scholar]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Castro, A.F., 3rd; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, E.D.; Ikizler, T.A.; Matheny, M.E.; Shi, Y.; Schildcrout, J.S.; Danciu, I.; Dwyer, J.P.; Srichai, M.; Hung, A.M.; Smith, J.P.; et al. Estimating baseline kidney function in hospitalized patients with impaired kidney function. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewington, A.; Kanagasundaram, S. Renal Association Clinical Practice Guidelines on acute kidney injury. Nephron 2011, 118 (Suppl. S1), c349–c390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäckel, M.; Aicher, N.; Rilinger, J.; Bemtgen, X.; Widmeier, E.; Wengenmayer, T.; Duerschmied, D.; Biever, P.M.; Stachon, P.; Bode, C.; et al. Incidence and predictors of delirium on the intensive care unit in patients with acute kidney injury, insight from a retrospective registry. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Kumar, S.; Ely, E.W.; Gezalian, M.M.; Lahiri, S. Acute kidney injury-associated delirium: A review of clinical and pathophysiological mechanisms. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Cozzi, M.; Bush, E.L.; Rabb, H. Distant Organ Dysfunction in Acute Kidney Injury: A Review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 72, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, S.; Wu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ding, S.; Feng, X.; Sun, L.; Tao, X.; Li, J.; et al. Change in serum level of interleukin 6 and delirium after coronary artery bypass graft. Am. J. Crit. Care 2019, 28, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, J.R. Delirium pathophysiology: An updated hypothesis of the etiology of acute brain failure. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 1428–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipser, C.M.; Deuel, J.; Ernst, J.; Schubert, M.; von Känel, R.; Böttger, S. The predisposing and precipitating risk factors for delirium in neurosurgery: A prospective cohort study of 949 patients. Acta Neurochir. 2019, 161, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziegielewski, C.; Skead, C.; Canturk, T.; Webber, C.; Fernando, S.M.; Thompson, L.H.; Foster, M.; Ristovic, V.; Lawlor, P.G.; Chaudhuri, D.; et al. Delirium and Associated Length of Stay and Costs in Critically Ill Patients. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2021, 2021, 6612187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiler, A.; Blum, D.; Deuel, J.W.; Hertler, C.; Schettle, M.; Zipser, C.M.; Ernst, J.; Schubert, M.; von Känel, R.; Boettger, S. Delirium is associated with an increased morbidity and in-hospital mortality in cancer patients: Results from a prospective cohort study. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 19, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gool, W.A.; van de Beek, D.; Eikelenboom, P. Systemic infection and delirium: When cytokines and acetylcholine collide. Lancet 2010, 375, 773–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachfalska, N.; Putowski, Z.; Krzych, Ł.J. Distant Organ Damage in Acute Brain Injury. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmarajan, K.; Swami, S.; Gou, R.Y.; Jones, R.N.; Inouye, S.K. Pathway from delirium to death: Potential in-hospital mediators of excess mortality. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Total Group (n = 942) | Delirium (n = 51) | No Delirium (n = 891) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [IQR], years | 65 [20] | 73 [14] | 65 [20] | 0.0003 * | ||

| Men, n (%) | 519 (55.1) | 32 (62.74) | 487 (54.65) | 0.311 | ||

| Smoking, n (%) | 38 (4.03) | 4 (7.84) | 34 (3.81) | 0.144 | ||

| Alcohol misuse, n (%) | 45 (4.77) | 9 (17.64) | 36 (4.04) | 0.0004* | ||

| Serum creatinine [IQR], (mg/dL) | 4.34 [4.99] | 5 [4.6] | 4.33 [4.99] | 0.275 | ||

| eGFR [IQR], (ml/min/1.73m2) | 11.88 [24.51] | 10.49 [19.58] | 11.98 [24.93] | 0.179 | ||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 833 (88.43) | 47 (92.15) | 786 (88.21) | 0.528 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 373 (39.60) | 20 (39.21) | 353 (39.62) | 0.954 | ||

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 361 (38.32) | 24 (47.06) | 337 (37.82) | 0.235 | ||

| Heart failure, n (%) | 352 (37.37) | 24 (47.06) | 328 (36.81) | 0.179 | ||

| History of stroke, n (%) | 124 (13.16) | 20 (39.21) | 104 (11.67) | <0.001 * | ||

| Vascular dementia, n (%) | 53 (5.62) | 9 (17.64) | 44 (4.94) | 0.0014 * | ||

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 767 (81.42) | 37 (72.55) | 730 (81.93) | 0.097 | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 46 (4.88) | 4 (7.84) | 42 (4.71) | 0.306 | ||

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 315 (33.44) | 10 (19.60) | 305 (34.23) | 0.032 | ||

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 39 (4.14) | 1 (1.96) | 38 (4.26) | 0.717 | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 72 (7.64) | 5 (9.80) | 67 (7.52) | 0.583 | ||

| Depression, n (%) | 83 (8.81) | 8 (15.68) | 75 (8.42) | 0.120 | ||

| Acute kidney injury, n (%) | 313 (33.22) | 32 (62.74) | 281 (31.54) | <0.001 * | ||

| AKI stage | AKI stage 1, n (%) | 22 (2.44) | 1 (1.96) | 21 (2.35) | 0.855 | |

| AKI stages 2 and 3, n (%) | 291 (30.90) | 31 (60.78) | 260 (29.18) | <0.001 * | ||

| Length of hospital stay [IQR], days | 9 [10.59] | 11.96 [9.62] | 8.88 [10.57] | 0.007 * | ||

| In-hospital mortality rate, n (%) | 152 (16.13) | 24 (47.05) | 128 (14.36) | <0.001 * | ||

| Parameter | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | OR (95%CI) | p | Beta | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Age (years) | 0.042 | 1.043 (1.019 to 1.068) | <0.001 | 0.028 | 1.029 (1.002 to 1.05) | 0.034 |

| AKI stages 2 and 3 KDIGO | 1.325 | 3.762 (2.105 to 6.721) | <0.001 | 0.777 | 2.175 (1.152 to 4.105) | 0.017 |

| Alcohol misuse | 1.627 | 5.089 (2.302 to 11.252) | <0.001 | 1.553 | 4.728 (1.968 to 1.359) | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.758 | 0.469 (0.232 to 0.948) | 0.035 | - | - | - |

| Vascular dementia | 1.417 | 4.125 (1.889 to 9.01) | <0.001 | - | - | - |

| History of stroke | 1.586 | 4.882 (2.684 to 8.89) | <0.001 | 1.251 | 3.493 (1.849 to 6.598) | <0.001 |

| Predictor | B | Wald | Hazard Ratio [95%CI] | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.032 | 18.322 | 1.032 [1.017–1.047] | <0.001 * |

| Baseline eGFR | −0.008 | 2.605 | 0.992 [0.982–1.002] | 0.107 |

| Delirium | 0.511 | 5.080 | 1.666 [1.069–2.597] | 0.024 * |

| Sepsis | 1.338 | 43.449 | 3.811 [2.560–5.673] | <0.001 * |

| AKI | 0.374 | 4.375 | 1.453 [1.024–2.062] | 0.036 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gadalean, F.; Petrica, L.; Milas, O.; Bob, F.; Parv, F.; Gluhovschi, C.; Suteanu-Simulescu, A.; Marcu, L.; Glavan, M.; Ienciu, S.; et al. The Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Short-Term Health Outcomes of Delirium in Patients Admitted to a Nephrology Ward in Eastern Europe: An Observational Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7303. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207303

Gadalean F, Petrica L, Milas O, Bob F, Parv F, Gluhovschi C, Suteanu-Simulescu A, Marcu L, Glavan M, Ienciu S, et al. The Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Short-Term Health Outcomes of Delirium in Patients Admitted to a Nephrology Ward in Eastern Europe: An Observational Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7303. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207303

Chicago/Turabian StyleGadalean, Florica, Ligia Petrica, Oana Milas, Flaviu Bob, Florina Parv, Cristina Gluhovschi, Anca Suteanu-Simulescu, Lavinia Marcu, Mihaela Glavan, Silvia Ienciu, and et al. 2025. "The Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Short-Term Health Outcomes of Delirium in Patients Admitted to a Nephrology Ward in Eastern Europe: An Observational Prospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7303. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207303

APA StyleGadalean, F., Petrica, L., Milas, O., Bob, F., Parv, F., Gluhovschi, C., Suteanu-Simulescu, A., Marcu, L., Glavan, M., Ienciu, S., Kigyosi, R., & Stanigut, A. (2025). The Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Short-Term Health Outcomes of Delirium in Patients Admitted to a Nephrology Ward in Eastern Europe: An Observational Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7303. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207303