Peer Relationships and Psychosocial Difficulties in Adolescents: Evidence from a Clinical Pediatric Sample

Abstract

1. Introduction

- H1: Higher friendship satisfaction predicts fewer difficulties.

- H2: Greater prosocial behavior predicts fewer difficulties.

- H3: Females report more difficulties than males.

- H4: Chronic illness, eating disorder risk, and substance use predict more difficulties.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L. Adolescence, 11th ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2016; 560p. [Google Scholar]

- Chmiel, M.; Kroplewski, Z. Personal Values and Psychological Well-Being Among Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Neale, M.C. Adolescent suicide behaviors associate with accelerated reductions in cortical gray matter volume and slower decay of behavioral activation Fun-Seeking scores. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.M.; Ross, D.; Hardy, R.; Kuh, D.; Power, C.; Johnson, A.; Wellings, K.; McCambridge, J.; Cole, T.J.; Kelly, Y.; et al. Life course epidemiology: Recognising the importance of adolescence. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 719–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H.; Bailey, V. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Goodman, R. Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, P.; Bharti, B.; Sidhu, M. Peer victimization among adolescents: Relational and physical aggression in Indian schools. Psychol. Stud. 2015, 60, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keilow, M.; Sievertsen, H.H.; Niclasen, J.; Obel, C. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and standardized academic tests: Reliability across respondent type and age. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zsakai, A.; Ratz-Sulyok, F.Z.; Koronczai, B.; Varro, P.; Toth, E.; Szarvas, S.; Tauber, T.; Karkus, Z.; Molnar, K. Risk and protective factors for health behaviour in adolescence in Europe. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Wang, Y. The development of behavioral problems in middle childhood: The role of early and recent stressors. J. Fam. Psychol. 2025, 39, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, B.; Collins, W.A. Parent–child relationships during adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 3rd ed.; Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.G.; Holland, A.; Brezinski, K.; Tu, K.M.; McElwain, N.L. Adolescent-Mother Attachment and Dyadic Affective Processes: Predictors of Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms. J. Youth Adolesc. 2025, 54, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.; Morris, A.S. Adolescent development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartup, W.W.; Stevens, N. Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Bukowski, W.M.; Parker, J.G. Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 6th ed.; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eisenberg, N., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 3, pp. 571–645. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell, C.L.; Schmidt, M.E. Friendships in Childhood and Adolescence; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zingora, T.; Flache, A. Effects of Friendship Influence and Normative Pressure on Adolescent Attitudes and Behaviors. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wentzel, K.R.; Barry, C.M.; Caldwell, K.A. Friendships in middle school: Influences on motivation and school adjustment. J. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 96, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentse, M.; Lindenberg, S.; Omvlee, A.; Ormel, J.; Veenstra, R. Rejection and acceptance across contexts: Parents and peers as risks and buffers for early adolescent psychopathology. The TRAILS study. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherewick, M.; Davenport, M.R.; Lama, R.; Giri, P.; Mukhia, D.; Rai, R.P.; Cruz, C.M.; Matergia, M. Control-Oriented and Escape-Oriented Coping: Links to Social Support and Mental Health in Early Adolescents. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L.; Knafo-Noam, A. Prosocial development. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, 7th ed.; Lerner, R.M., Lamb, M.E., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 610–656. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Carlo, G. Prosocial development: A multidimensional approach. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Development and Culture; Jensen, L.A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 206–221. [Google Scholar]

- von Rezori, R.E.; Baumeister, H.; Holl, R.W.; Meissner, T.; Minden, K.; Mueller-Stierlin, A.S.; Temming, S.; Warschburger, P. Prospective associations between coping, benefit-finding and growth, and subjective well-being in youths with chronic health conditions: A two-wave cross-lagged analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2025, jsaf087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surís, J.C.; Michaud, P.A.; Viner, R. The adolescent with a chronic condition. Part I: Developmental issues. Arch. Dis. Child. 2004, 89, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Shen, Y. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: An updated meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassin, L.; Pitts, S.C.; Prost, J. Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: Predictors and substance abuse outcomes. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Boden, J.M.; Horwood, L.J. The developmental antecedents of illicit drug use: Evidence from a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2008, 96, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Campana, B.R.; Argentiero, A.; Masetti, M.; Fainardi, V.; Principi, N. Too young to pour: The global crisis of underage alcohol use. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1598175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, M. Alcohol use among adolescents and young adults. Alcohol. Res. Health 2003, 27, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt, L.; Coffey, C.; Romaniuk, H.; Swift, W.; Carlin, J.B.; Hall, W.D.; Patton, G.C. The persistence of the association between adolescent cannabis use and common mental disorders into young adulthood. Addiction 2013, 108, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Storr, C.L.; Anthony, J.C. Early-onset drug use and risk for drug dependence problems. Addict. Behav. 2009, 34, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Drew, S.; Yeo, M.S.; Britto, M.T. Adolescents with a chronic condition: Challenges living, challenges treating. Lancet 2007, 369, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebli, K.; Gritti, A.; Calia, C. Bridging cultural sensitivity and ethical practice: Expert narratives on child and adolescent mental health in Kuwait. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiang, L.; Fuligni, A.J. Ethnic identity and family processes among adolescents from Latin American, Asian, and European backgrounds. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, L.; Speltini, G. Parental attachment, self-esteem and social competence: Relationships between variables in the Italian context. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 15, 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Brener, N.D.; Billy, J.O.G.; Grady, W.R. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: Evidence from the scientific literature. J. Adolesc. Health 2003, 33, 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.F.; Reid, F.; Lacey, J.H. The SCOFF questionnaire: A new screening tool for eating disorders. West. J. Med. 2000, 172, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannocchia, L.; Fiorino, M.; Giannini, M.; Vanderlinden, J. A psychometric exploration of an Italian translation of the SCOFF questionnaire. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2011, 19, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, L.; Rollo, S.; Cafeo, A.; Di Rosa, G.; Pino, R.; Gagliano, A.; Germanò, E.; Ingrassia, M. Emotional and behavioural factors predisposing to internet addiction: The smartphone distraction among Italian high school students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, G.; Arigliani, E.; Martinelli, M.; Di Noia, S.; Chiarotti, F.; Cardona, F. Daydreaming and psychopathology in adolescence: An exploratory study. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2023, 17, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essau, C.A.; Olaya, B.; Pasha, G.; Gilvarry, C.; Bray, D. The structure of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in adolescents from five ethnic groups. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 199, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Cerniglia, L.; Cimino, S. Eating disorders and internalizing/externalizing symptoms in adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2023, 42, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Anna, G.; Lazzeretti, M.; Castellini, G.; Ricca, V.; Cassioli, E.; Rossi, E.; Silvestri, C.; Voller, F. Risk of eating disorders in a representative sample of Italian adolescents: Prevalence and association with self-reported interpersonal factors. Eat. Weight Disord. 2022, 27, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 4th ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Yohai, V.J. High breakdown-point and high efficiency robust estimates for regression. Ann. Stat. 1987, 15, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M.; Stahel, W.A. Sharpening Wald-type inference in robust regression for small samples. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2011, 55, 2504–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1987, 82, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; Version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Santucci, K.; Dirks, M.A.; Lydon, J.E. With or without you: Understanding friendship dissolution from childhood through young adulthood. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2025, 42, 2675–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwabueze, K.K.; Akubue, N.; Onakoya, A.; Okolieze, S.C.; Otaniyen-Igbinoba, I.J.; Chukwunonye, C.; Okengwu, C.G.; Ige, T.; Alao, O.J.; Adindu, K.N. Exploring the prevalence and risk factors of adolescent mental health issues in the COVID and post-COVID era in the U.K.: A systematic review. EXCLI J. 2025, 24, 508–523. [Google Scholar]

- Carlo, G.; Crockett, L.J.; Randall, B.A.; Roesch, S.C. A latent growth curve analysis of prosocial behavior among rural adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2007, 17, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Jia, Q.; Li, C. Examining the Interaction Between Perceived Neighborhood Disorder, Positive Peers, and Self-Esteem on Adolescent Prosocial Behavior: A Study of Chinese Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, E.; Qi, H.; Zhao, L.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; You, X. The longitudinal relationship between adolescents’ prosocial behavior and well-being: A cross-lagged panel network analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2025, 54, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmott-Elison, M.K.; Holmgren, H.G.; Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Hawkins, A.J. Associations between prosocial behavior, externalizing behaviors, and internalizing symptoms during adolescence: A meta-analysis. J. Adolesc. 2020, 80, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn-Waxler, C.; Shirtcliff, E.A.; Marceau, K. Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 275–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.S.; Mezulis, A.H.; Abramson, L.Y. The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 115, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puntoni, M.; Esposito, S.; Patrizi, L.; Palo, C.M.; Deolmi, M.; Autore, G.; Fainardi, V.; Caminiti, C.; On Behalf of the University Hospital of Parma Long-Covid Research Team. Impact of Age and Sex Interaction on Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19: An Italian Cohort Study on Adults and Children. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Girgus, J.S. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.J.; Rudolph, K.D. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 98–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.; Ma, H.K. Parent-adolescent conflict and adolescent antisocial and prosocial behavior: A longitudinal study in a Chinese context. Adolescence 2001, 36, 545–555. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, M.D.; Bearman, P.S.; Blum, R.W.; Bauman, K.E.; Harris, K.M.; Jones, J.; Tabor, J.; Beuhring, T.; Sieving, R.E.; Shew, M.; et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA 1997, 278, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C.; Hoyo, Á.; Tapia-Sanz, M.E.; Jiménez-González, A.I.; Moral, B.J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, P.; Vargas-Hernández, Y.; Ruiz-Sánchez, L.J. An update on the underlying risk factors of eating disorders onset during adolescence: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1221679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, A.; Rock, A.J.; Davies, R.; Rice, K. Psychometric evaluation of the ‘Caregiver Factors Influencing Treatment’ (Care-FIT) Inventory for child and adolescent eating disorders. J. Eat. Disord. 2025, 13, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.; Ford, T.; Simmons, H.; Gatward, R.; Meltzer, H. Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) to screen for child psychiatric disorders in a community sample. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.P.; Antonishak, J. Adolescent peer influences: Beyond the dark side. In Understanding Peer Influence in Children and Adolescents; Prinstein, M.J., Dodge, K.A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, R.F.; Berglund, M.L.; Ryan, J.A.M.; Lonczak, H.S.; Hawkins, J.D. Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2004, 591, 98–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Thomson, K.C. Understanding the link between social and emotional well-being and peer relations in early adolescence: Gender-specific predictors of peer acceptance. J. Youth Adolesc. 2010, 39, 1330–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesi, J.; Choukas-Bradley, S.; Prinstein, M.J. Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: Part 1—A theoretical framework and application to dyadic peer relationships. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 21, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables | ||

| Age (years) | 12.51 | 1.11 |

| SDQ Total Difficulties | 10.62 | 5.46 |

| Prosocial behavior (SDQ) | 7.62 | 1.99 |

| Mother-relationship satisfaction | 4.37 | 0.83 |

| Father-relationship satisfaction | 4.21 | 0.96 |

| Friendship satisfaction | 4.22 | 0.88 |

| Categorical variables | n | % |

| Sex (Female) | 77 | 43.5 |

| Italian citizenship (Yes) | 165 | 93.2 |

| Chronic condition (Yes) | 127 | 71.8 |

| Eating-disorder risk (SCOFF ≥ 3) | 41 | 23.2 |

| Alcohol use, lifetime (Yes) | 35 | 19.8 |

| Alcohol use, past year (Yes) | 24 | 13.6 |

| Alcohol use, past 30 days (Yes) | 16 | 9.0 |

| Nicotine use, lifetime (Yes) | 18 | 10.2 |

| Nicotine use, past year (Yes) | 14 | 7.9 |

| Nicotine use, past 30 days (Yes) | 13 | 7.4 |

| Cannabis use, lifetime (Yes) | 3 | 1.7 |

| Cannabis use, past year (Yes) | 2 | 1.1 |

| Cannabis use, past 30 days (Yes) | 2 | 1.1 |

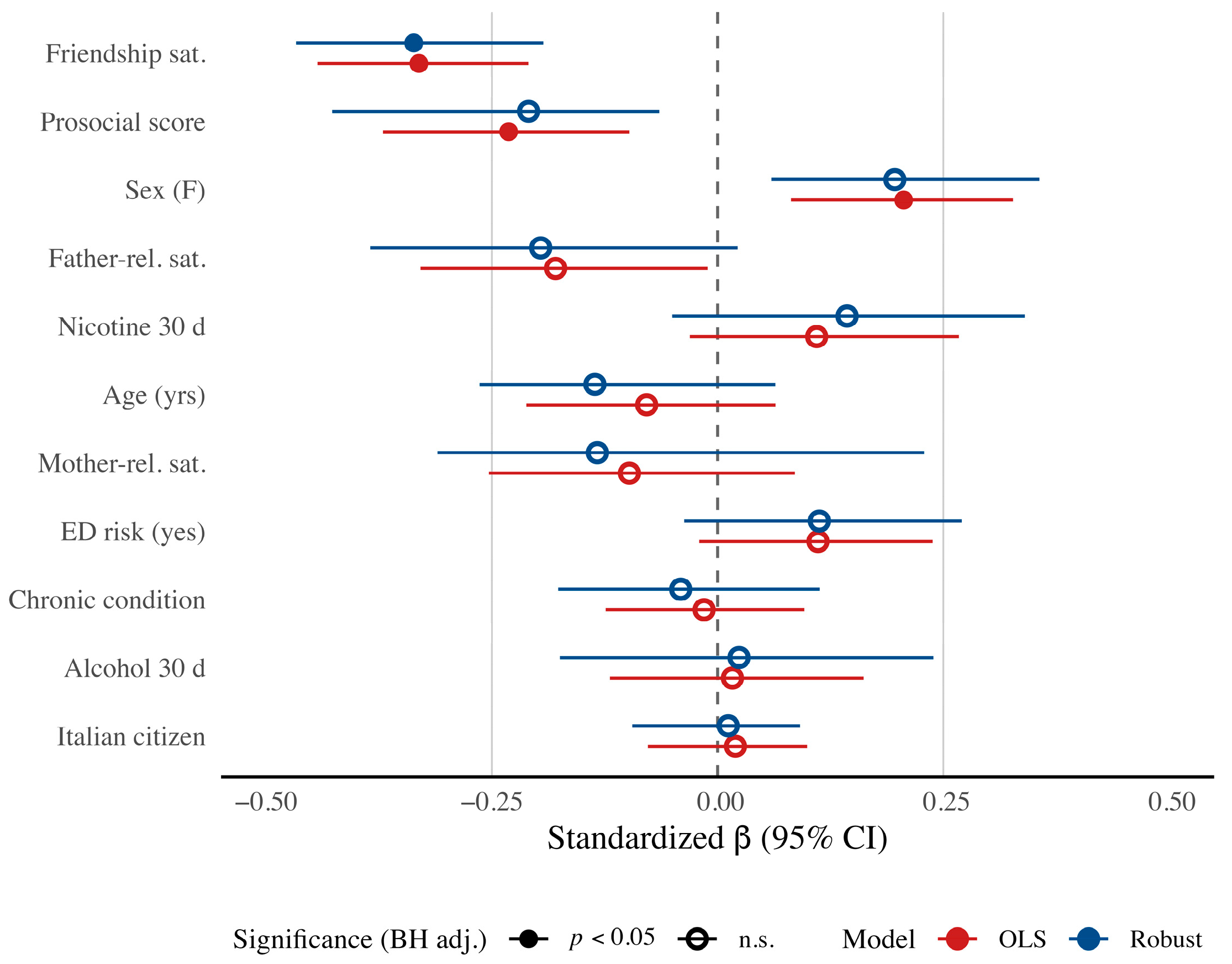

| Predictor | B(SE) | 95% CI | pBH | β | Δ a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 34.24 | (5.24) | [23.73, 44.21] | — | — | — |

| Age | −0.39 | (0.34) | [−1.03, 0.33] | 0.362 | −0.08 | 0.28 |

| Sex | 2.30 | (0.70) | [0.91, 3.70] | 0.002 | 0.21 | 0.14 |

| Chronic condition | −0.16 | (0.68) | [−1.45, 1.21] | 0.788 | −0.02 | 0.33 |

| Italian citizenship | 0.43 | (1.00) | [−1.77, 2.18] | 0.788 | 0.02 | 0.17 |

| Mother-relationship satisfaction | −0.68 | (0.56) | [−1.61, 0.61] | 0.362 | −0.10 | 0.20 |

| Father-relationship satisfaction | −1.00 | (0.47) | [−1.87, −0.03] | 0.054 | −0.18 | 0.11 |

| Friendship satisfaction | −2.05 | (0.35) | [−2.71, −1.31] | <0.001 | −0.33 | 0.04 |

| Eating-disorder risk | 1.39 | (0.87) | [−0.35, 3.04] | 0.210 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Prosocial behavior score | −0.64 | (0.20) | [−1.04,−0.27] | 0.006 | −0.23 | 0.07 |

| Alcohol use (30 d) | 0.45 | (1.46) | [−2.24, 3.56] | 0.788 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Nicotine use (30 d) | 2.29 | (1.61) | [−0.77, 5.55] | 0.298 | 0.11 | 0.73 |

| Model fit: R2 = 0.41, adj. R2 = 0.37; F(11, 165) = 10.49, p < 0.001. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tadonio, L.; Giudice, A.; Infantino, C.; Pilloni, S.; Verdesca, M.; Patianna, V.; Gerra, G.; Esposito, S. Peer Relationships and Psychosocial Difficulties in Adolescents: Evidence from a Clinical Pediatric Sample. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7177. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207177

Tadonio L, Giudice A, Infantino C, Pilloni S, Verdesca M, Patianna V, Gerra G, Esposito S. Peer Relationships and Psychosocial Difficulties in Adolescents: Evidence from a Clinical Pediatric Sample. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7177. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207177

Chicago/Turabian StyleTadonio, Leonardo, Antonella Giudice, Claudia Infantino, Simone Pilloni, Matteo Verdesca, Viviana Patianna, Gilberto Gerra, and Susanna Esposito. 2025. "Peer Relationships and Psychosocial Difficulties in Adolescents: Evidence from a Clinical Pediatric Sample" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7177. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207177

APA StyleTadonio, L., Giudice, A., Infantino, C., Pilloni, S., Verdesca, M., Patianna, V., Gerra, G., & Esposito, S. (2025). Peer Relationships and Psychosocial Difficulties in Adolescents: Evidence from a Clinical Pediatric Sample. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7177. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207177