Determinants of Social Activity Among Geriatric Patients in Northern Romania: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

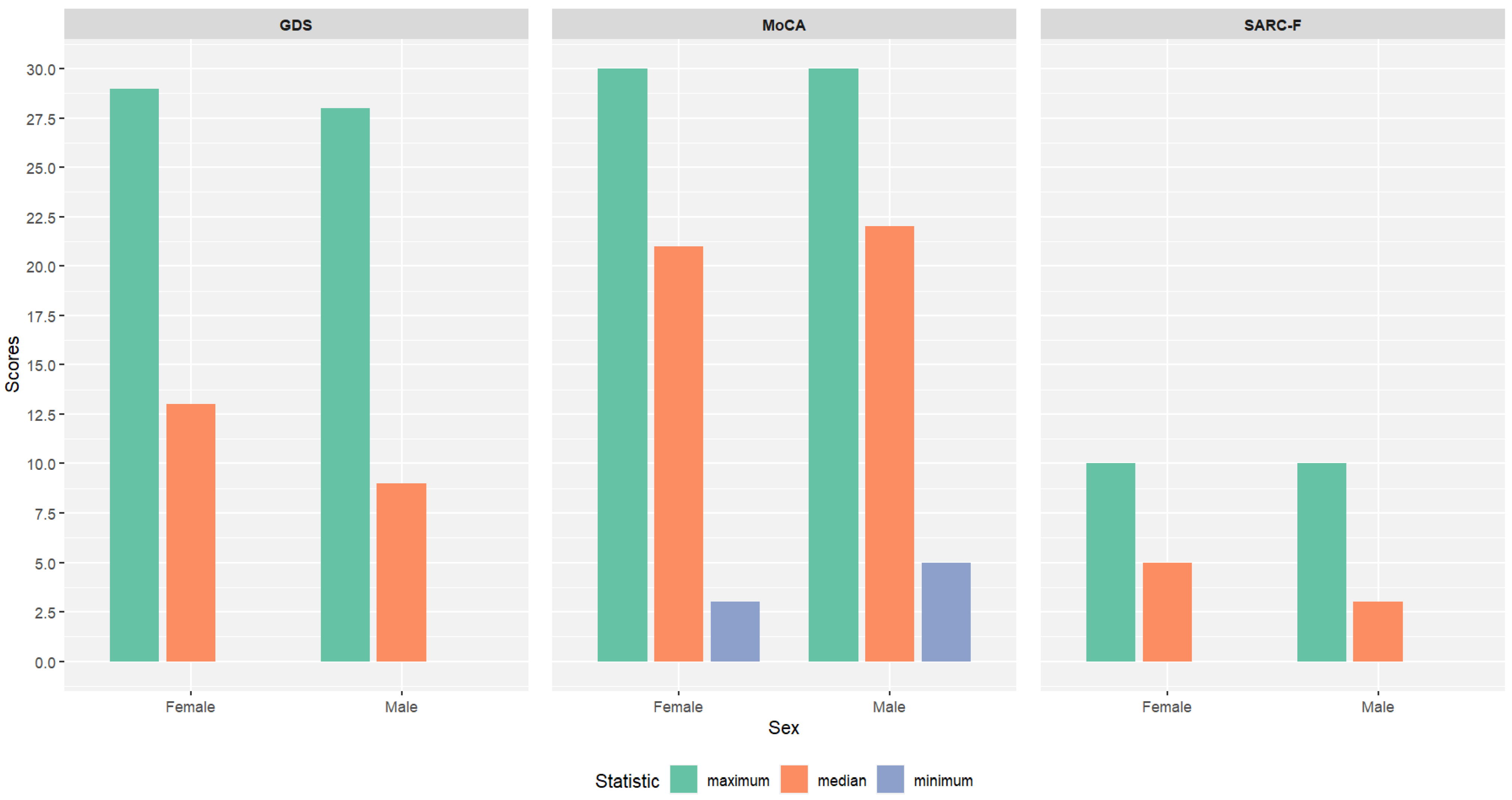

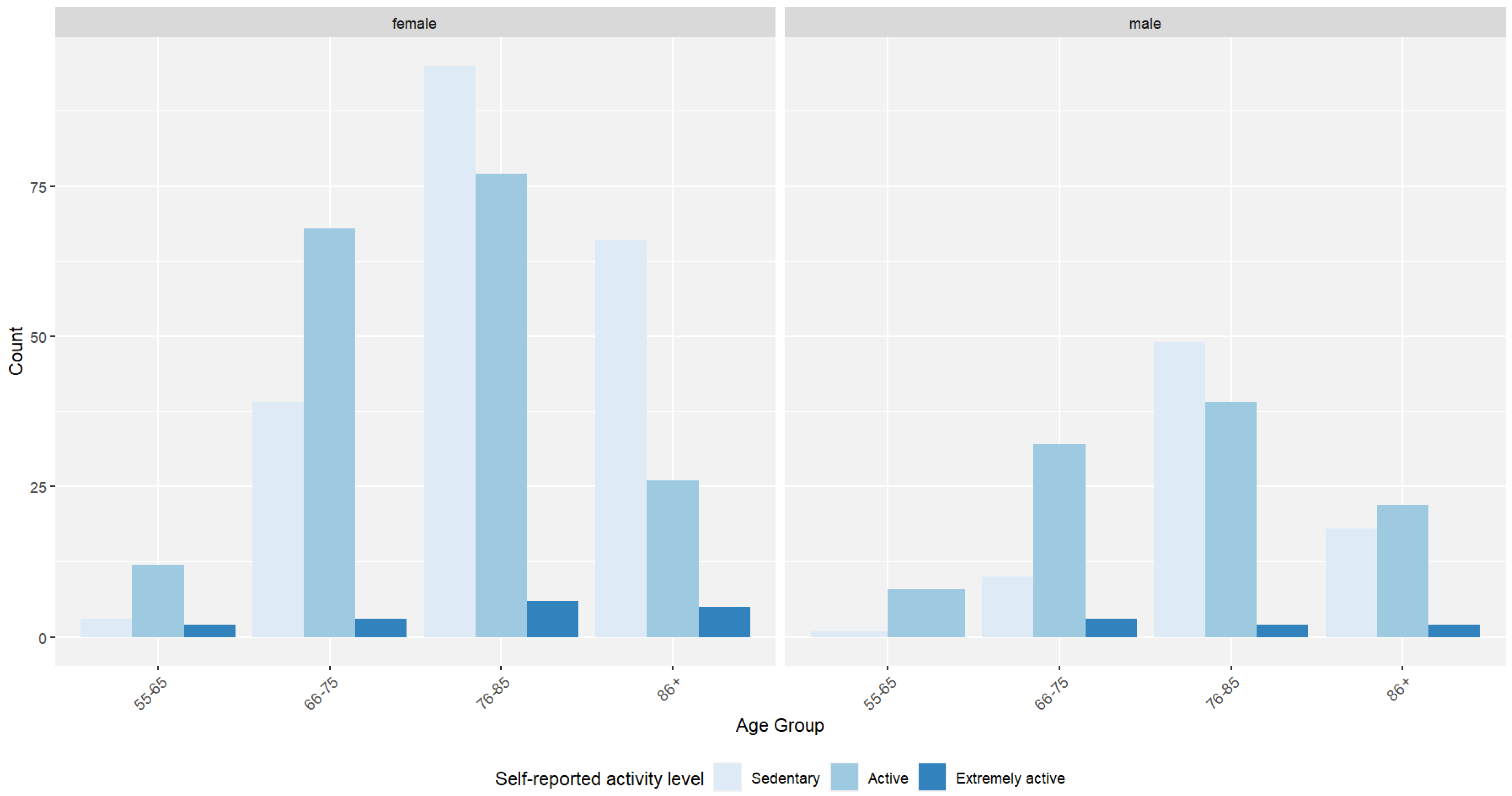

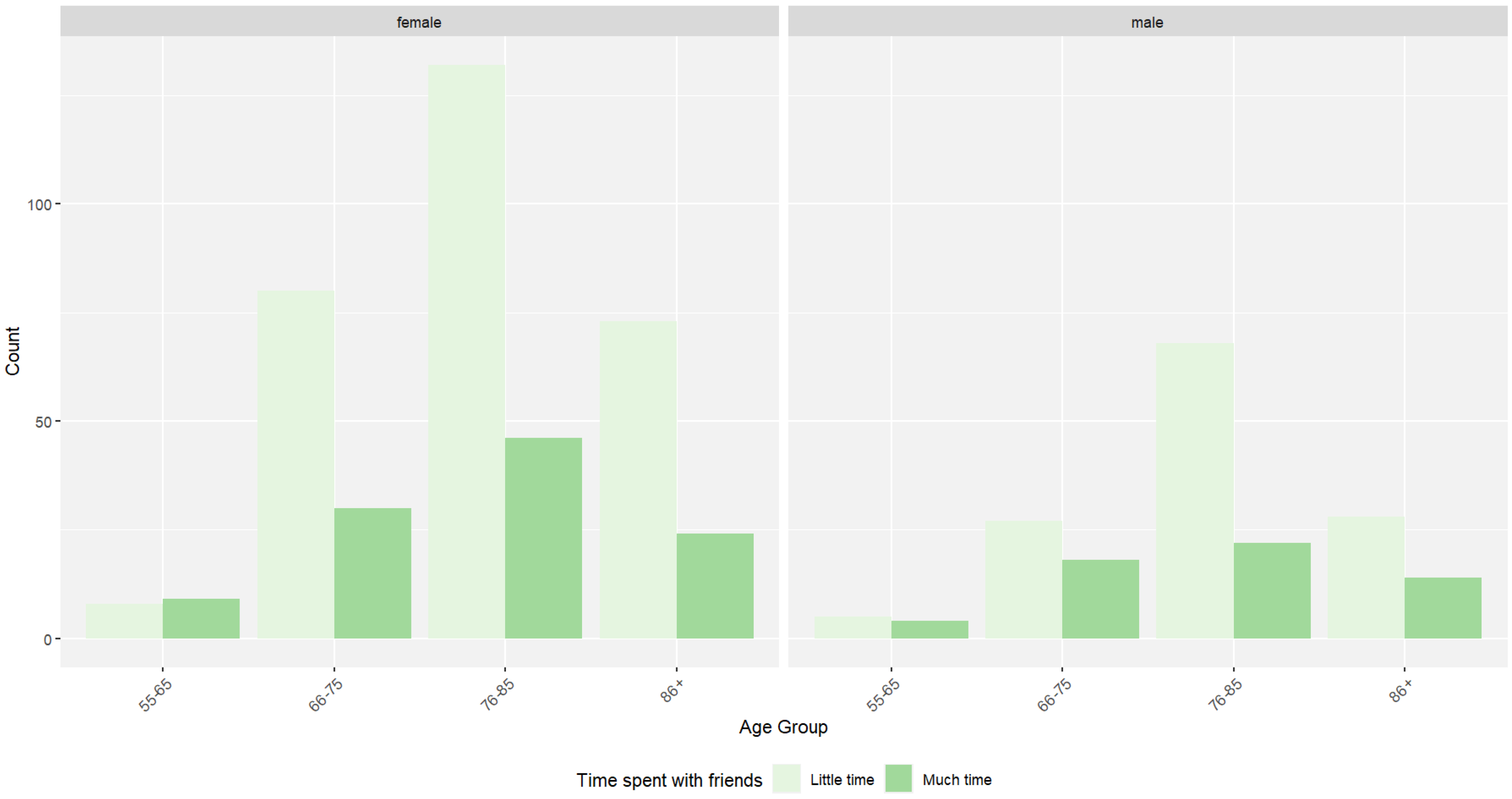

3.1. Descriptive Statistics, Group Comparisons, and Associations

3.2. Results of Linear Regressions

3.3. Results of Binary Logistic Regression

3.4. Results of Multinominal Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Țăruș, R.; Dezsi, Ș.; Pop, F. Ageing Urban Population Prognostic between 2020 and 2050 in Transylvania Region (Romania). Sustainability 2021, 13, 9940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, A.N.; Jaeggi, S.M. Activity Engagement and Cognitive Performance Amongst Older Adults. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 620867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, R.; Prado-Cabrero, A.; Mulcahy, R.; Howard, A.; Nolan, J.M. The Role of Nutrition for the Aging Population: Implications for Cognition and Alzheimer’s Disease. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juma, F.; Fernández-Sainz, A. Social Exclusion Among Older Adults: A Multilevel Analysis for 10 European Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 174, 525–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unequal Romania: Regional Socio-Economic Disparities in Romania [Internet]. Foundation for European Progressive Studies. Available online: https://feps-europe.eu/publication/800-unequal-romania-regional-socio-economic-disparities-in-romania/ (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Avram, L.; Ungureanu, M.I.; Crişan, D.; Donca, V. Assessment of Frailty Scores Among Geriatric Patients Hospitalized in the North-Western Region of Romania: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoene, D.; Heller, C.; Aung, Y.N.; Sieber, C.C.; Kemmler, W.; Freiberger, E. A systematic review on the influence of fear of falling on quality of life in older people: Is there a role for falls? Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, X.; Dang, M.; Zhao, S.; Sang, F.; Zhang, Z. Frontotemporal structure preservation underlies the protective effect of lifetime intellectual cognitive reserve on cognition in the elderly. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, L.; Cutler, S.J. Older Adults and the Digital Divide in Romania: Implications for the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Elder Policy 2021, 1, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Tak, S.H. A concept analysis of fear of falling in older adults: Insights from qualitative research studies. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damme, M.V.; Spijker, J.; Pavlopoulos, D. A Care Regime Typology of Elder, Long-Term Care Institutions [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3981497/v1 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Hărăguș, M.; Telegdi-Csetri, V. Intergenerational Solidarity in Romanian Transnational Families. In Making Multicultural Families in Europe: Gender and Intergenerational Relations; Crespi, I., Giada Meda, S., Merla, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, M.; Lotfaliany, M.; Mohebbi, M.; Reynolds, C.F.; Woods, R.L.; Orchard, S.; Chong, T.; Agustini, B.; O’Neil, A.; Ryan, J. Depressive symptoms and cognitive decline in older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.Y.; Chen, D.R.; Chan, C.C.; Yeh, Y.P.; Chen, H.H. Fear of falling as a mediator in the association between social frailty and health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, R. Fear of Falls and Frailty: Cause or Consequence or Both? J. Aging Res. Healthc. 2021, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, N.J.; Blazer, D. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Review and Commentary of a National Academies Report. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education and Socioeconomic Status Factsheet. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/education (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- The Risks of Social Isolation. Available online: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/05/ce-corner-isolation (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1982, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Rajaa, S.; Rehman, T. Diagnostic accuracy of various forms of geriatric depression scale for screening of depression among older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 87, 104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ștefan, A.M.; Băban, A. The Romanian version of the Geriatric Depression Scale: Reliability and validity. Cogn. Brain Behav. Interdiscip. J. 2017, 21, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichitvejpaisal, P.; Preechakoon, B.; Supaprom, W.; Sriputtaruk, S.; Rodpaewpaln, S.; Saen-Ubol, R.; Vessuwan, K. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment as a Screening Tool for Preoperative Cognitive Impairment in Geriatric Patients. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2015, 98, 782–789. [Google Scholar]

- Koski, L.; Xie, H.; Finch, L. Measuring Cognition in a Geriatric Outpatient Clinic: Rasch Analysis of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2009, 22, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, L.; Adel, M.V.; Metcalf, V.; Wright, L.; Harley, A.; Leiva, R.; Taler, V. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in geriatric rehabilitation: Psychometric properties and association with rehabilitation outcomes. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23, 1582–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, A.M.; Jacobson, S.A.; Hentz, J.G.; Belden, C.M.; Shill, H.A.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Caviness, J.N.; Adler, C.H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the mini-mental state examination as screening instruments for cognitive impairment: Item analyses and threshold scores. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2011, 31, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmstrom, T.K.; Morley, J.E. SARC-F: A Simple Questionnaire to Rapidly Diagnose Sarcopenia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparik, A.; Demián, M.B.; Pascanu, I. ROMANIAN TRANSLATION AND VALIDATION OF THE SARC-F QUESTIONNAIRE. Acta Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, L.; Ravona-Springer, R.; Lin, H.M.; Liu, X.; Sano, M.; Heymann, A.; Schnaider Beeri, M. Specific Dimensions of Depression Have Different Associations With Cognitive Decline in Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpino, B.; Solé-Auró, A. Education Inequalities in Health Among Older European Men and Women: The Role of Active Aging. J. Aging Health 2019, 31, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Qing, N.; Zhang, S. The Impact of Leisure Activities on the Mental Health of Older Adults: The Mediating Effect of Social Support and Perceived Stress. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6264447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Guo, Y.; Tian, Z. Loneliness or Sociability: The Impact of Social Participation on the Mental Health of the Elderly Living Alone. Health Soc. Care Community 2024, 2024, 5614808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.; Jung, S.H.; Shim, I.; Cha, S.; Lee, H.; Kim, B.; Yoon, J.; Ha, T.H.; et al. Genome-wide association study of occupational attainment as a proxy for cognitive reserve. Brain 2022, 145, 1436–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco, P.M.; Crespo, D.P.; García, A.I.R.; Ibáñez, M.L.; Rubio, B.M.; Montenegro-Peña, M. Predictive factors and risk and protection groups for loneliness in older adults: A population-based study. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartweg, D.L.; Metcalfe, S.A. Orem’s Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory: Relevance and Need for Refinement. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2022, 35, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Dong, S.; Su, W.; Guan, W.; Yu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, H.; Ma, G. Relationship between social participation and depressive symptoms in patients with multimorbidity: The chained mediating role of cognitive function and activities of daily living. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xiang, Q.; Song, Q.; Liang, R.; Deng, L.; Dong, B.; Yue, J. Longitudinal associations between social support and sarcopenia: Findings from a 5-year cohort study in Chinese aged ≥50 years. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2024, 28, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Abudukelimu, N.; Sali, A.; Chen, J.-X.; Li, M.; Mao, Y.-Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, Q.-X. Sociodemographic features associated with the MoCA, SPPB, and GDS scores in a community-dwelling elderly population. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.H.; Liao, Y.; Chang, S.H. Cross-sectional association of physical activity levels with risks of sarcopenia among older Taiwanese adults. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demurtas, J.; Schoene, D.; Torbahn, G.; Marengoni, A.; Grande, G.; Zou, L.; Petrovic, M.; Maggi, S.; Cesari, M.; Lamb, S.; et al. Physical Activity and Exercise in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: An Umbrella Review of Intervention and Observational Studies. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1415–1422.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourouklis, D.; Verropoulou, G.; Tsimbos, C. The impact of wealth and income on the depression of older adults across European welfare regimes. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 2448–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moreno, E.; Gallardo-Peralta, L.P. Income inequalities, social support and depressive symptoms among older adults in Europe: A multilevel cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Ageing 2021, 19, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Female | Male | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.755 | ||

| 55–65 years | 17 (2.89%) | 9 (1.53%) | |

| 66–75 years | 110 (18.71%) | 45 (7.65%) | |

| 76–85 years | 178 (30.27%) | 90 (15.31%) | |

| 86+ years | 97 (16.5%) | 42 (7.14%) | |

| Settlement type | 0.7043 | ||

| Urban | 236 (40.14%) | 113 (19.22%) | |

| Rural | 166 (28.23%) | 73 (12.41%) | |

| Education | 0.0005 | ||

| No education | 4 (0.68%) | 2 (0.34%) | |

| Primary school | 83 (14.12%) | 23 (3.91%) | |

| Gymnasium | 145 (24.66%) | 67 (11.39%) | |

| High school | 126 (21.43%) | 56 (9.52%) | |

| University | 41 (6.97%) | 37 (6.29%) | |

| Postgrad | 3 (0.51%) | 1 (0.17%) | |

| Pension | p < 0.0005 | ||

| 0–1000 RON | 9 (1.53%) | 4 (0.68%) | |

| 1001–2000 RON | 206 (35.03%) | 35 (5.95%) | |

| 2001–3000 RON | 113 (19.22%) | 71 (12.07%) | |

| 3001–4000 RON | 52 (8.84%) | 43 (7.31%) | |

| 4001–5000 RON | 15 (2.55%) | 14 (2.38%) | |

| 5001–6000 RON | 5 (0.85%) | 10 (1.70%) | |

| 6001–9000 RON | 2 (0.34%) | 9 (1.53%) | |

| Civil status | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Not married | 6 (1.02%) | 8 (1.36%) | |

| Married | 111 (18.88%) | 107 (18.2%) | |

| Divorced | 18 (3.06%) | 7 (1.19%) | |

| Widow(er) | 267 (45.41%) | 64 (10.88%) | |

| Living conditions | 0.6254 | ||

| House | 246 (41.84%) | 111 (18.88%) | |

| Apartment building—elevator | 52 (8.84%) | 21 (3.57%) | |

| Apartment building—first level | 23 (3.91%) | 11 (1.87%) | |

| Apartment building—no elevator | 78 (13.27%) | 39 (6.63%) | |

| Long-term care facility | 3 (0.51%) | 4 (0.68%) | |

| Self-reported activity level | 0.1357 | ||

| Sedentary | 203 (34.52%) | 78 (13.27%) | |

| Active | 183 (31.12%) | 101 (17.18%) | |

| Extremely active | 16 (2.72%) | 7 (1.19%) | |

| Time spent with friends | 0.3581 | ||

| Little time | 293 (49.83%) | 128 (21.77%) | |

| Much time | 109 (18.54%) | 58 (9.86%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donca, V.; Grad, D.A.; Ungureanu, M.I.; Bodolea, C.; Hirişcău, E.I.; Avram, L. Determinants of Social Activity Among Geriatric Patients in Northern Romania: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020565

Donca V, Grad DA, Ungureanu MI, Bodolea C, Hirişcău EI, Avram L. Determinants of Social Activity Among Geriatric Patients in Northern Romania: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(2):565. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020565

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonca, Valer, Diana Alecsandra Grad, Marius I. Ungureanu, Constantin Bodolea, Elisabeta Ioana Hirişcău, and Lucreţia Avram. 2025. "Determinants of Social Activity Among Geriatric Patients in Northern Romania: A Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 2: 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020565

APA StyleDonca, V., Grad, D. A., Ungureanu, M. I., Bodolea, C., Hirişcău, E. I., & Avram, L. (2025). Determinants of Social Activity Among Geriatric Patients in Northern Romania: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020565