Continuous Stitches Versus Simple Interrupted Stitches During Anterior Colporrhaphy: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

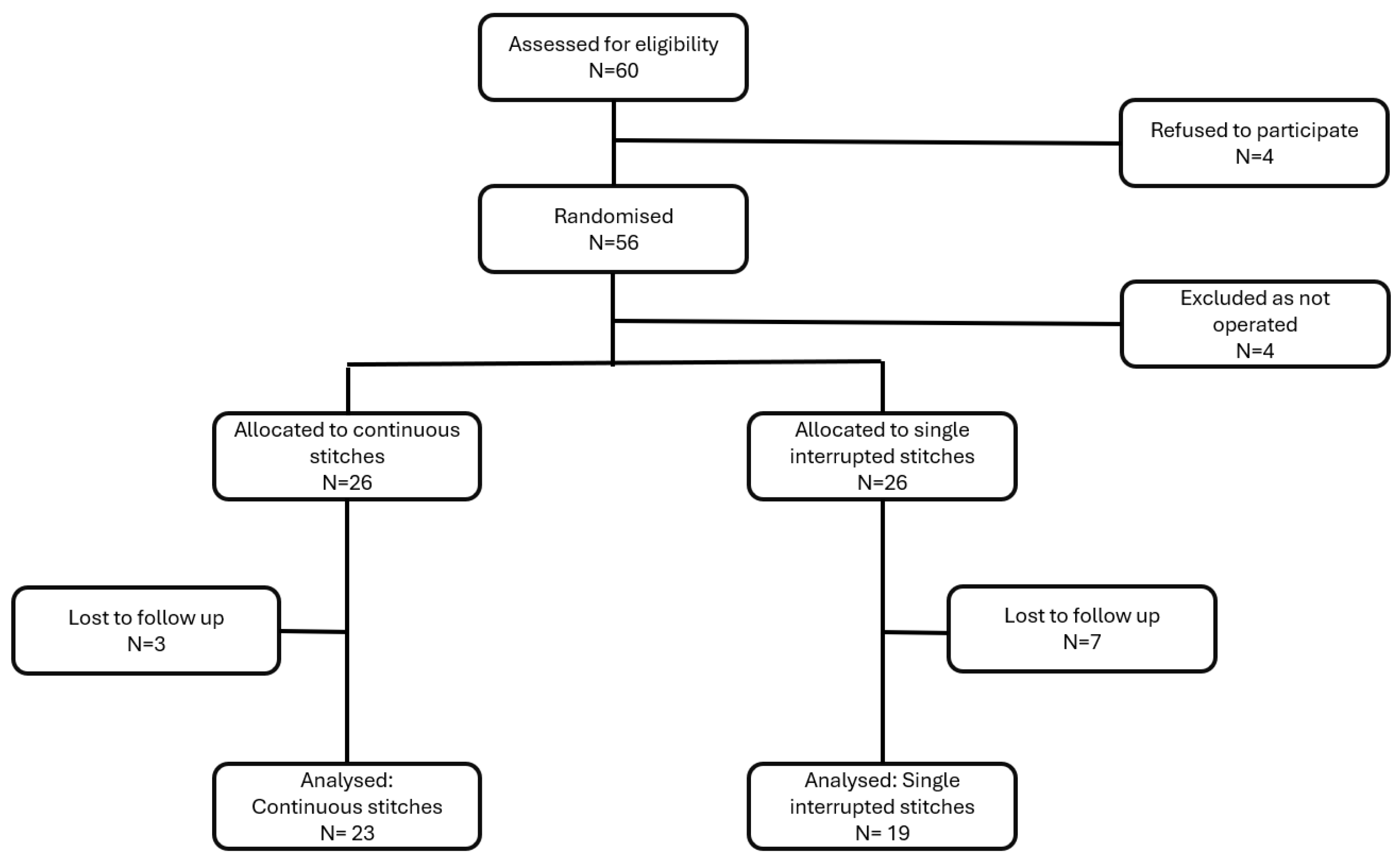

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Randomization

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures

2.6. Sample Size and Power Considerations

2.7. Data Analysis

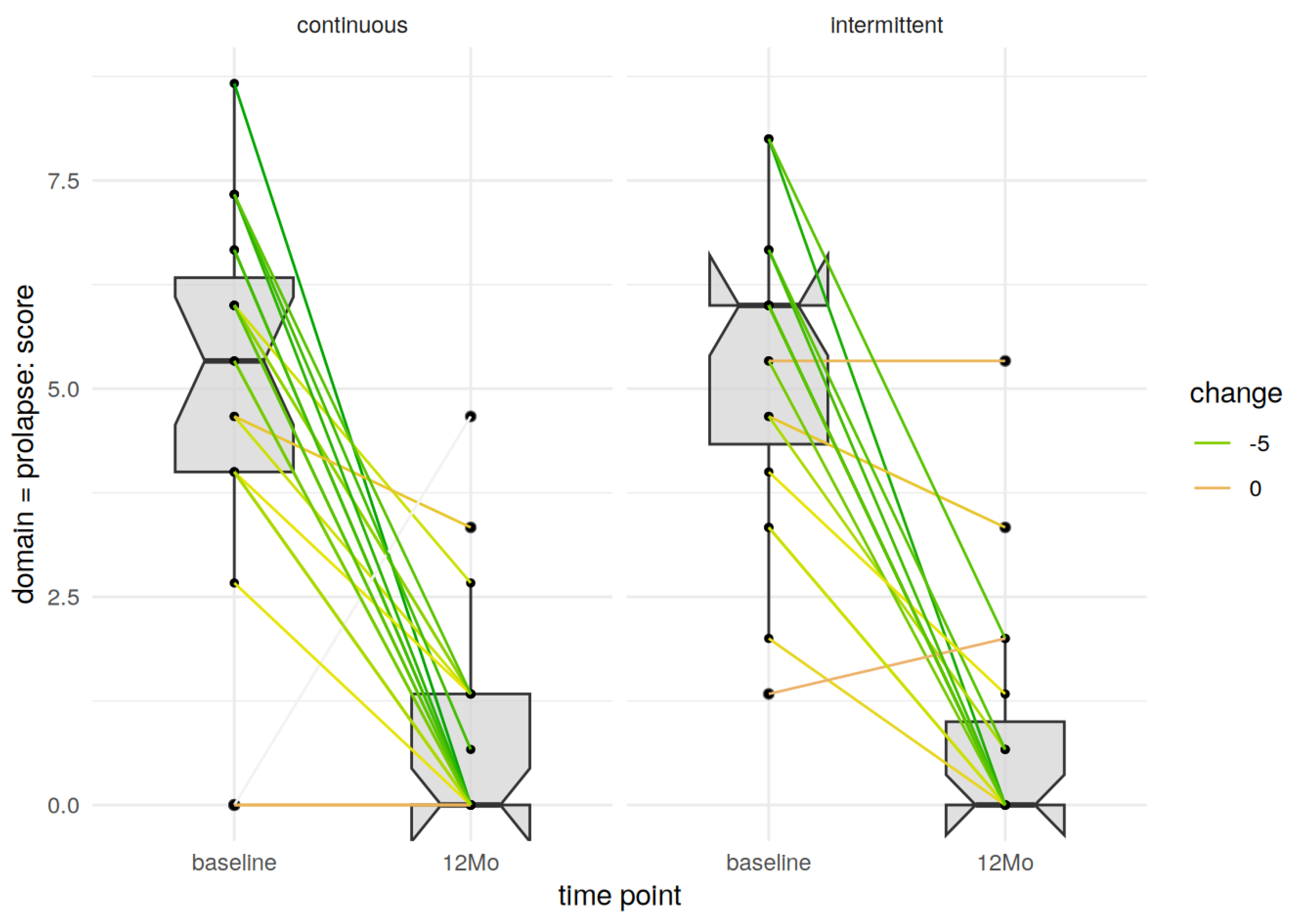

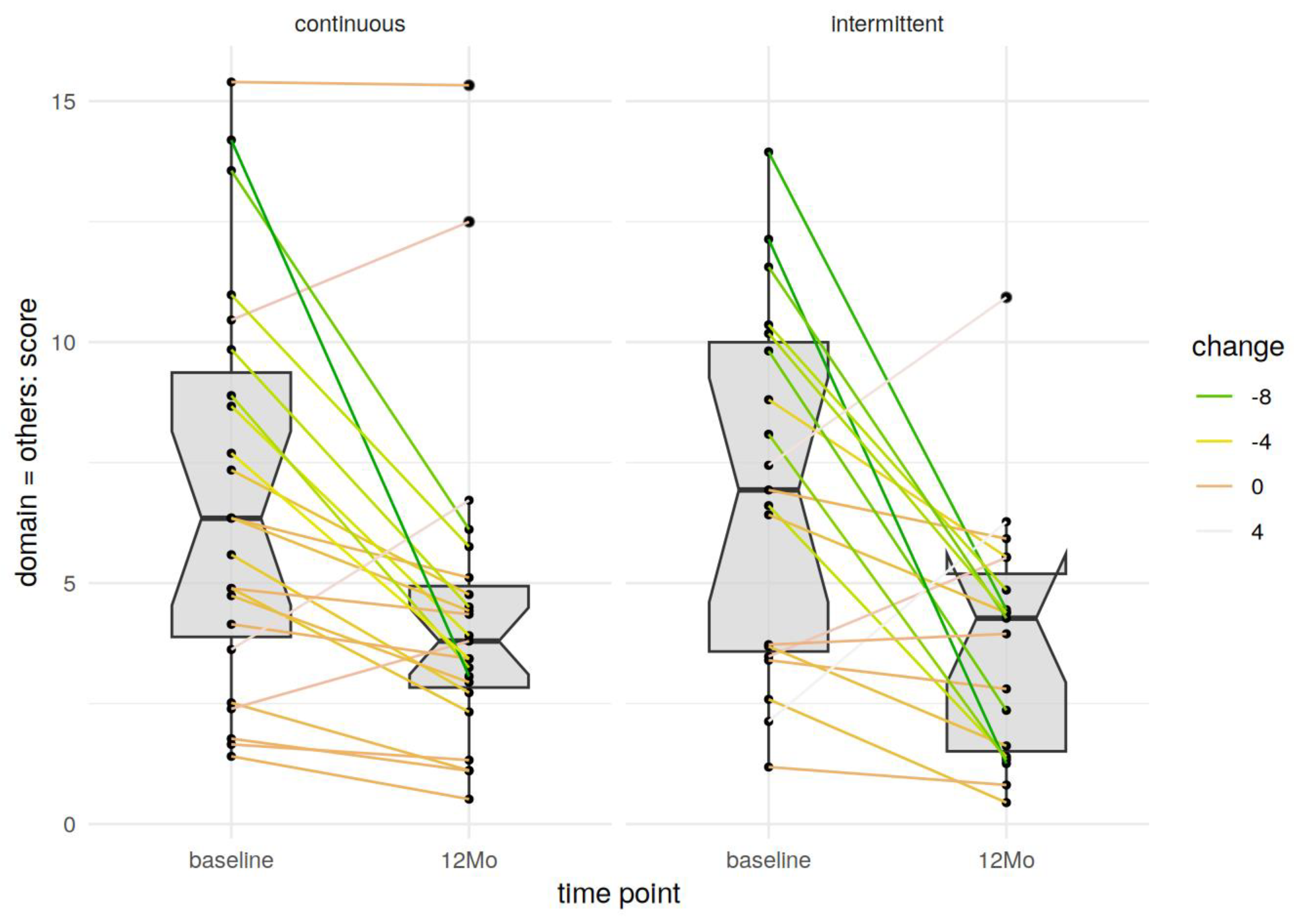

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, F.J.; Holman, C.D.; Moorin, R.E.; Tsokos, N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 116, 1096–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, S.L.; Clark, A.; Nygaard, I.; Aragaki, A.; Barnabei, V.; McTiernan, A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: Gravity and gravidity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensen, E.J.; Stoutjesdijk, J.A.; Withagen, M.I.; Kluivers, K.B.; Vierhout, M.E. Technique of anterior colporrhaphy: A Dutch evaluation. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2011, 22, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weber, A.M.; Walters, M.D. Anterior vaginal prolapse: Review of anatomy and techniques of surgical repair. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 89, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Itza, I.; Aizpitarte, I.; Becerro, A. Risk factors for the recurrence of pelvic organ prolapse after vaginal surgery: A review at 5 years after surgery. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2007, 18, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.; Seitz, M.; Tran, A.; Scalabrin Reis, R.; Botros, C.; Lozo, S.; Botros, S.; Sand, P.; Tomezsko, J.; Wang, C.; et al. Anterior Colporrhaphy With and Without Dermal Allograft: A Randomized Control Trial With Long-Term Follow-Up. Urogynecology 2019, 25, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern-Elenskaia, K.; Umek, W.; Bodner-Adler, B.; Hanzal, E. Anterior colporrhaphy: A standard operation? Systematic review of the technical aspects of a common procedure in randomized controlled trials. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, E.; Segar, J.; Myers, J.; Smith, A.; Reid, F. Surgical technique used in the UK for native tissue anterior pelvic organ prolapse repair (VaST). Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, C.; Hills, R.K.; Ismail, K.M. Continuous versus interrupted sutures for repair of episiotomy or second degree tears. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, CD000947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, C.; Dowswell, T.; Ismail, K.M. Continuous and interrupted suturing techniques for repair of episiotomy or second-degree tears. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11, CD000947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, P.; Saiz Puente, M.S.; Valero, J.L.; Azorin, R.; Ortega, R.; Guijarro, R. Continuous versus interrupted sutures for repair of episiotomy or second-degree perineal tears: A randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2009, 116, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graefe, F.; Schwab, F.; Tunn, R. Double-layered anterior colporrhaphy (DAC)-video and mid-term follow-up of 60 patients. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023, 34, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valtersson, E.; Husby, K.R.; Elmelund, M.; Klarskov, N. Evaluation of suture material used in anterior colporrhaphy and the risk of recurrence. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, S.; Morris, S.; McKinnie, V.; Freeman, R.; Petri, E.; Scotti, R.J.; Dwyer, P. Validation of a simplified technique for using the POPQ pelvic organ prolapse classification system. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2006, 17, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baessler, K.; Kempkensteffen, C. Validation of a comprehensive pelvic floor questionnaire for the hospital, private practice and research. Gynäkologisch-Geburtshilfliche Rundschau 2009, 49, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld, M.; Fuermetz, A.; Muenster, M.; Ennemoser, S.; von Bodungen, V.; Friese, K.; Jundt, K. Sexuality in German urogynecological patients and healthy controls: Is there a difference with respect to the diagnosis? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 170, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, W. Tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the ‘Tidyverse’. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tidyverse/index.html (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Simon, G. Viridis: Colorblind-Friendly Color Maps for R. 2024. Available online: http://ravenports.ironwolf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Gohel, D.; Skintzos, P. Flextable: Functions for Tabular Reporting. 2024. Available online: https://davidgohel.github.io/flextable/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Gohel, D.; Moog, S.; Heckmann, M.; Hangler, F.; Sander, L.; Victorson, A.; Calder, J.; Harrold, J.; Muschelli, J.; Denney, B.; et al. Officer: Manipulation of Microsoft Word and PowerPoint Documents. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/davidgohel/officer (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Kamil, E. Barnard: Barnard’s Unconditional Test. 2016. Available online: https://scholar.google.ca/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=th&user=XS9bwjUAAAAJ&citation_for_view=XS9bwjUAAAAJ:_kc_bZDykSQC (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Diez-Itza, I.; Avila, M.; Uranga, S.; Belar, M.; Lekuona, A.; Martin, A. Factors involved in prolapse recurrence one year after anterior vaginal repair. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 2027–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.D.; Brubaker, L.; Nygaard, I.; Wheeler, T.L., 2nd; Schaffer, J.; Chen, Z.; Spino, C.; Pelvic Floor Disorders, N. Defining success after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelovsek, J.E.; Maher, C.; Barber, M.D. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet 2007, 369, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Guo, L. Risk factors for the recurrence of pelvic organ prolapse: A meta-analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 43, 2160929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All | Interrupted Single Stitches | Continuous Stitches | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 42 | 19 | 23 | ||

| Age | median (IQR) | 62.5 (54–71) | 63 (52–71.5) | 62 (56–70.5) | 0.9496 |

| [95% CI] | [58–66] | [52–72] | [58–70] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Parity | median (IQR) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (1.5–2) | 0.3201 |

| [95% CI] | [2–2] | [2–3] | [2–2] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| BMI | median (IQR) | 25.3 (23.13–26.82) | 25.4 (22.55–26.6) | 25.2 (23.36–27.05) | 0.6766 |

| [95% CI] | [23.8–26.3] | [22–26.9] | [23.4–26.6] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Menopausal Status | premenopausal median (IQR) | 8 (19.05%) | 6 (31.58%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0.0445 |

| perimenopausal median (IQR) | 30 (71.43%) | 13 (68.42%) | 17 (73.91%) | ||

| postmenopausal median (IQR) | 4 (9.52%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (17.39%) | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| HRT | No | 28 (66.67%) | 10 (52.63%) | 18 (78.26%) | 0.0977 |

| Yes | 14 (33.33%) | 9 (47.37%) | 5 (21.74%) | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Smoking | No | 35 (83.33%) | 14 (73.68%) | 21 (91.3%) | 0.1510 |

| Yes | 7 (16.67%) | 5 (26.32%) | 2 (8.7%) | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Previous hysterectomy | No | 40 (95.24%) | 19 (100%) | 21 (91.3%) | 0.2181 |

| Yes | 2 (4.76%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.7%) | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Previous incontinence operation | No | 20 (47.62%) | 9 (47.37%) | 11 (47.83%) | 0.9943 |

| Yes | 22 (52.38%) | 10 (52.63%) | 12 (52.17%) | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Comorbidities | No | 38 (90.48%) | 16 (84.21%) | 22 (95.65%) | 0.2557 |

| Yes | 4 (9.52%) | 3 (15.79%) | 1 (4.35%) | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| PFQ all domains but prolapse | median (IQR) | 6.51 (3.64–9.84) | 6.93 (3.58–10) | 6.34 (3.88–9.37) | 0.8201 |

| [95% CI] | [4.74–8.67] | [3.48–10.18] | [4.15–8.89] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| PFQ bladder | median (IQR) | 2.67 (0.94–4.89) | 2.67 (1.78–3.89) | 2.67 (0.89–4.89) | 10.000 |

| [95% CI] | [2–4] | [1.56–4] | [0.89–4.89] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| PFQ bowel | median (IQR) | 2.21 (0.96–2.87) | 2.35 (1.03–4.12) | 1.76 (1.03–2.5) | 0.3281 |

| [95% CI] | [1.18–2.65] | [0.88–4.71] | [1.18–2.35] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| PFQ prolapse | median (IQR) | 5.67 (4–6) | 6 (4.33–6) | 5.33 (4–6.33) | 0.8380 |

| [95% CI] | [4.67–6] | [4–6] | [4–6] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| PFQ sex | median (IQR) | 1.43 (0–2.38) | 0.95 (0–2.14) | 1.43 (0–2.62) | 0.6406 |

| [95% CI] | [0–2.38] | [0–2.38] | [0–2.38] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| POP-Q stage | median (IQR) | 3 (2.25–3) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (3–3) | 0.0366 |

| [95% CI] | [3–3] | [2–3] | [3–3] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| All | Interrupted Single Stitches | Continuous Stitches | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 42 | 19 | 23 | ||

| Operation time | median (IQR) | 73.5 (60.25–85.75) | 75 (61.5–87.5) | 73 (59.5–84.5) | 0.7234 |

| [95% CI] | [68–77] | [61–95] | [60–82] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Uterine sparing surgery | no | 12 (28.57%) | 5 (26.32%) | 7 (30.43%) | 0.8202 |

| yes | 30 (71.43%) | 14 (73.68%) | 16 (69.57%) | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| CDC | 0 | 20 (47.62%) | 10 (52.63%) | 10 (43.48%) | 0.0230 |

| 1 | 12 (28.57%) | 8 (42.11%) | 4 (17.39%) | ||

| 2 | 10 (23.81%) | 1 (5.26%) | 9 (39.13%) | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Adverse events | Bleeding | 6 (24%) | 3 (27.27%) | 3 (21.43%) | 0.0150 |

| Incomplete bladder emptying | 4 (16%) | 3 (27.27%) | 1 (7.14%) | ||

| Infection/granulation tissue | 2 (8%) | 2 (18.18%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Stress incontinence | 2 (8%) | 2 (18.18%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| UTI | 10 (40%) | 1 (9.09%) | 9 (64.29%) | ||

| Vaginal wound dehiscence | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.14%) | ||

| NA | 17 (40.48%) | 8 (42.11%) | 9 (39.13%) | ||

| postOP PFQ all domains but prolapse | median (IQR) | 3.93 (2.33–5.05) | 4.27 (1.51–5.19) | 3.8 (2.83–4.94) | 0.8201 |

| [95% CI] | [2.94–4.45] | [1.4–5.53] | [2.94–4.76] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| postOP PFQ bladder | median (IQR) | 1.56 (0.67–2.33) | 1.33 (0.56–2) | 1.78 (1.33–2.44) | 0.3224 |

| [95% CI] | [1.33–2] | [0.44–2] | [1.56–2.44] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| postOP PFQ bowel | median (IQR) | 1.47 (0.59–2.35) | 1.47 (0.59–2.35) | 1.47 (0.74–2.21) | 0.6847 |

| [95% CI] | [1.18–2.06] | [0.59–2.35] | [0.88–2.06] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| postOP PFQ prolaps | median (IQR) | 0 (0–1.33) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1.33) | 0.9307 |

| [95% CI] | [0–0.67] | [0–1.33] | [0–1.33] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| postOP PFQ sex | median (IQR) | 0 (0–0.48) | 0 (0–0.24) | 0.48 (0–0.95) | 0.0741 |

| [95% CI] | [0–0.48] | [0–0.48] | [0–0.95] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| postOP POP-Q stage | median (IQR) | 2 (1.25–2) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–2) | 0.2570 |

| [95% CI] | [2–2] | [1–2] | [2–2] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Difference in postOP PFQ all domains but prolapse | median (IQR) | −2.05 (−5.31–−0.55) | −2.14 (−6.27–−0.48) | −1.8 (−4.51–−0.6) | 0.4950 |

| [95% CI] | [−4.26–−0.89] | [−6.76–−0.37] | [−4.26–−0.67] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Difference in postOP PFQ prolapse | median (IQR) | −5 (−6–−2.83) | −6 (−6–−3) | −4.67 (−6–−3) | 0.8986 |

| [95% CI] | [−6–−3.33] | [−6–−2.67] | [−6–−3.33] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Difference in postOP POP-Q stage | median (IQR) | −1 (−1–0) | −1 (−2–0) | −1 (−1–−0.5) | 0.9030 |

| [95% CI] | [−1–−1] | [−2–0] | [−1–−1] | ||

| NA | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Predictor | Estimate | CI Low | CI High | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous stitches | 0.133 | −1.182 | 1.496 | 0.845 |

| Age | −0.027 | −0.079 | 0.025 | 0.312 |

| Baseline POP-Q stage | −0.235 | −1.785 | 1.374 | 0.768 |

| Baseline pelvic floor questionnaire prolapse domain | −0.086 | −0.395 | 0.228 | 0.583 |

| Predictor | Estimate | CI Low | CI High | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous stitches | 0.694 | −0.540 | 1.976 | 0.286 |

| Age | 0.037 | −0.010 | 0.088 | 0.143 |

| Baseline POP-Q stage | −0.880 | −2.316 | 0.495 | 0.226 |

| Baseline pelvic floor questionnaire all other domains but prolapse | 0.262 | 0.096 | 0.442 | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bekos, C.; Lange, S.; Koch, M.; Umek, W.; Carlin, G.L.; Heinzl, F.; Bodner-Adler, B. Continuous Stitches Versus Simple Interrupted Stitches During Anterior Colporrhaphy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020534

Bekos C, Lange S, Koch M, Umek W, Carlin GL, Heinzl F, Bodner-Adler B. Continuous Stitches Versus Simple Interrupted Stitches During Anterior Colporrhaphy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(2):534. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020534

Chicago/Turabian StyleBekos, Christine, Sören Lange, Marianne Koch, Wolfgang Umek, Greta Lisa Carlin, Florian Heinzl, and Barbara Bodner-Adler. 2025. "Continuous Stitches Versus Simple Interrupted Stitches During Anterior Colporrhaphy: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 2: 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020534

APA StyleBekos, C., Lange, S., Koch, M., Umek, W., Carlin, G. L., Heinzl, F., & Bodner-Adler, B. (2025). Continuous Stitches Versus Simple Interrupted Stitches During Anterior Colporrhaphy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020534