Motivation to Clinical Trial Participation: Health Information Distrust and Healthcare Access as Explanatory Variables and Gender as Moderator

Abstract

1. Background

1.1. Clinical Trial Diversity

1.2. Current Efforts to Promote Diversity and Persistent Underrepresentation

1.3. Motivational Factors and Barriers

1.4. Study Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Study Sample

2.4. Study Measures

2.4.1. Outcome Variable

2.4.2. Predictors

Sociodemographic Variables

Health Status Variables

2.4.3. Healthcare Relations Explanatory Variables

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

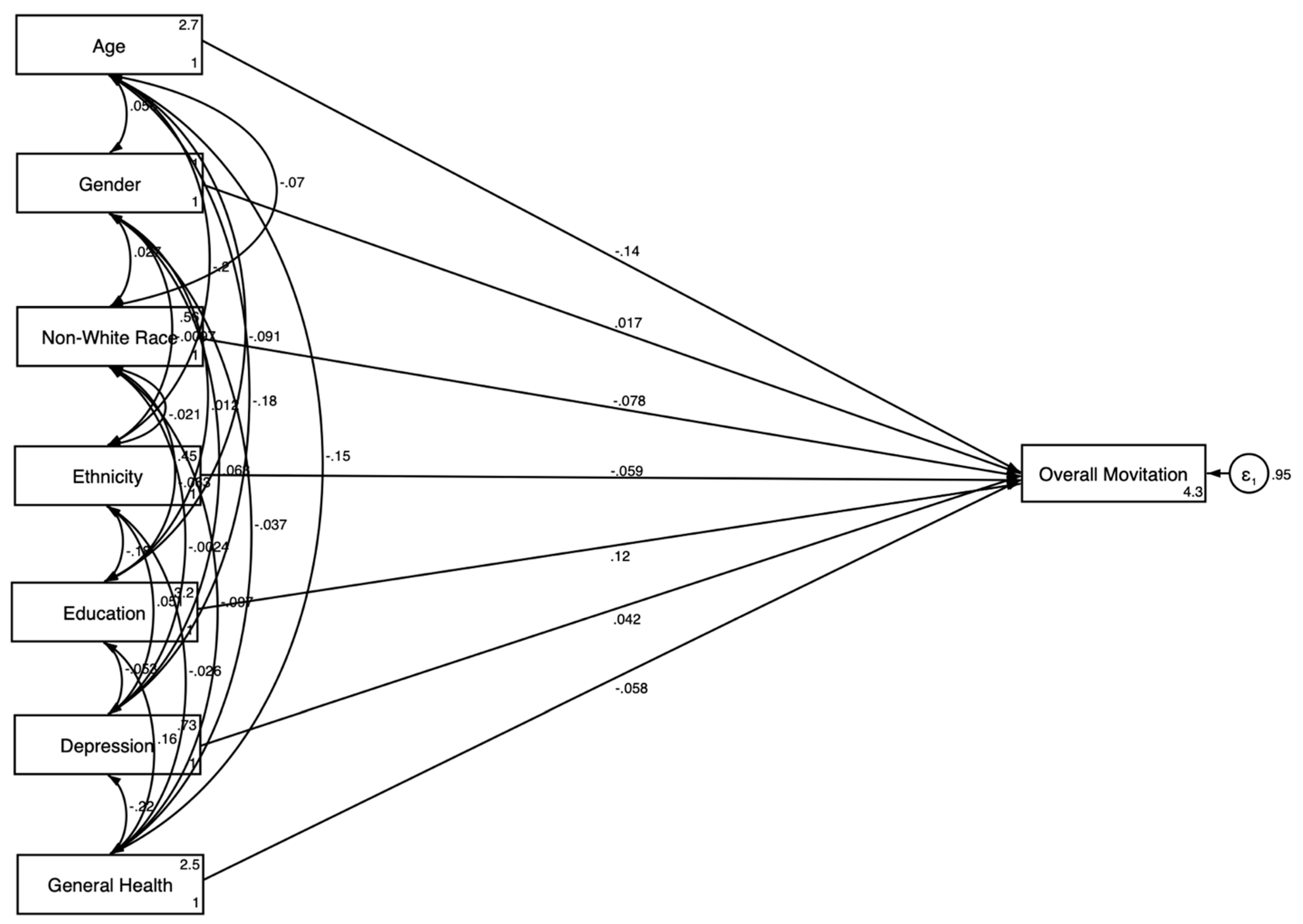

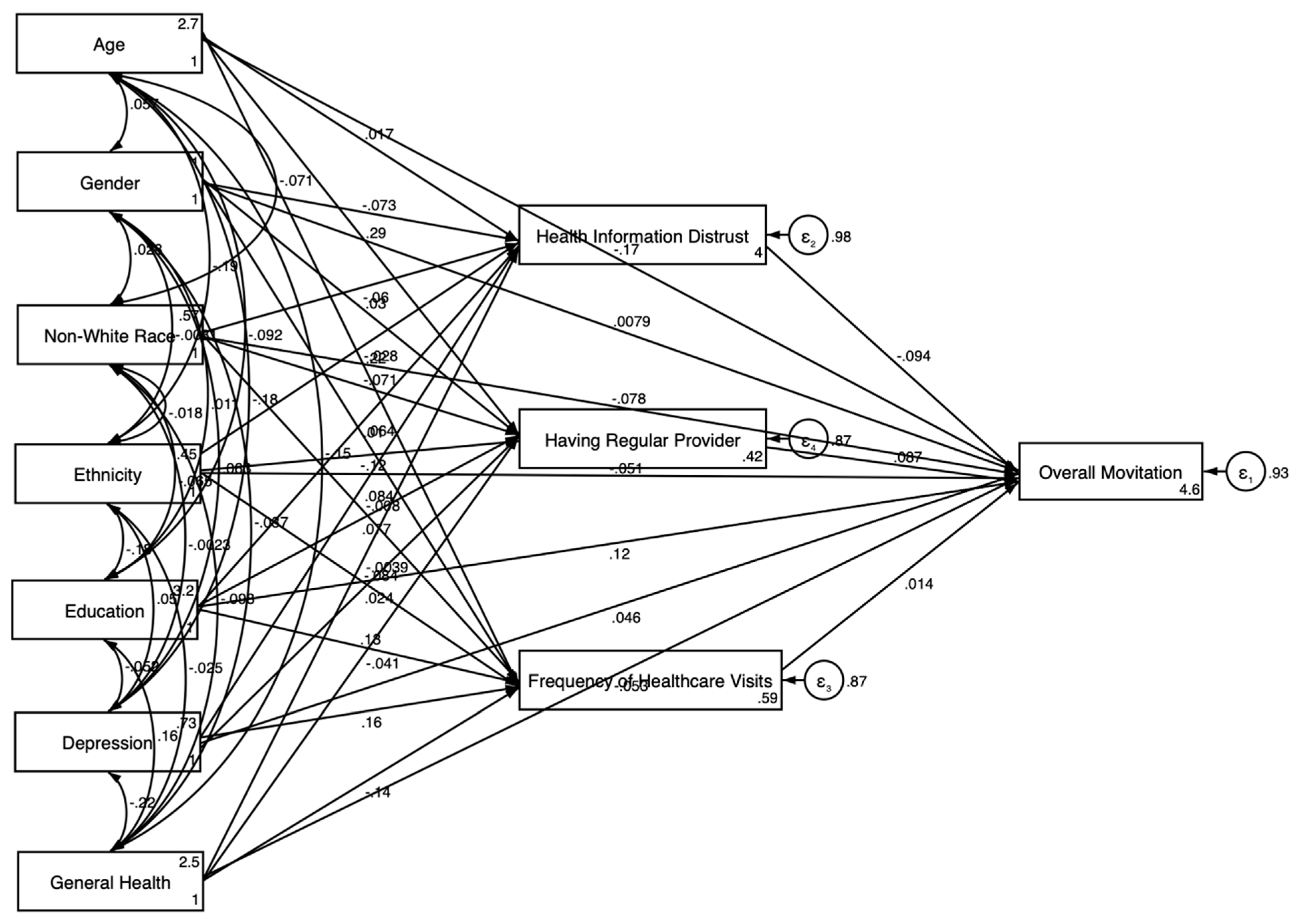

3.2. Pooled SEM Results

3.3. Gender-Stratified SEM Results

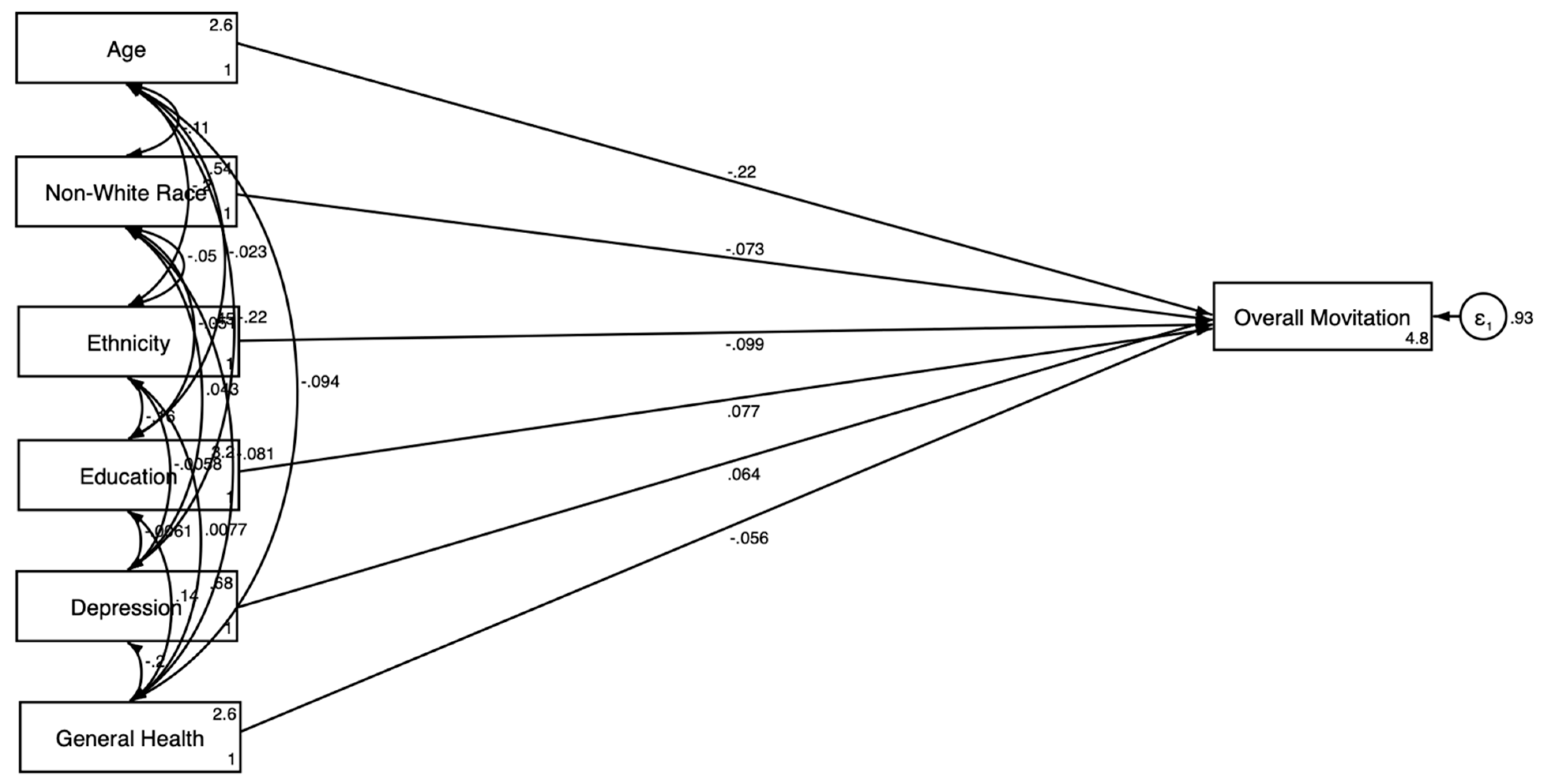

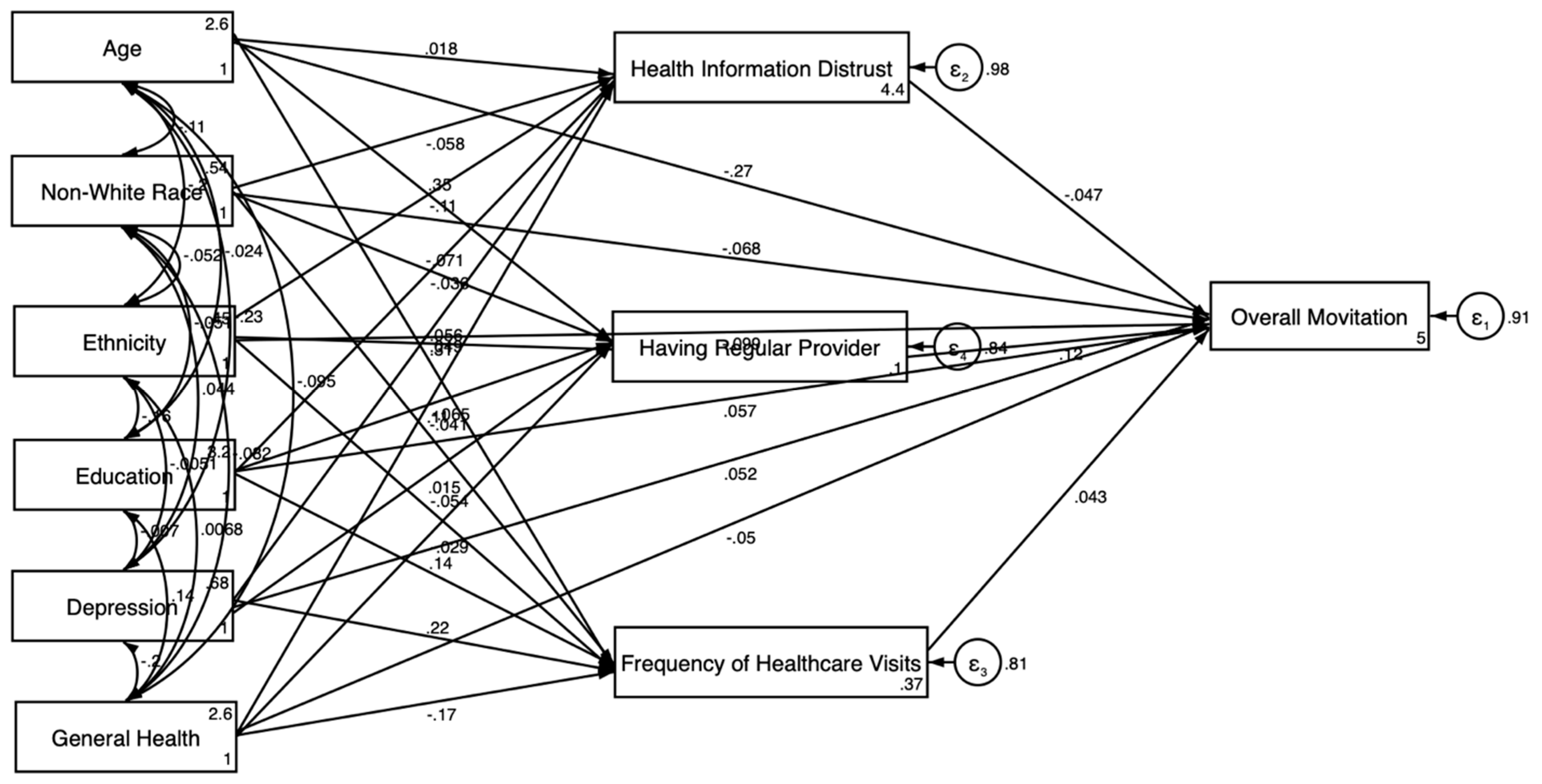

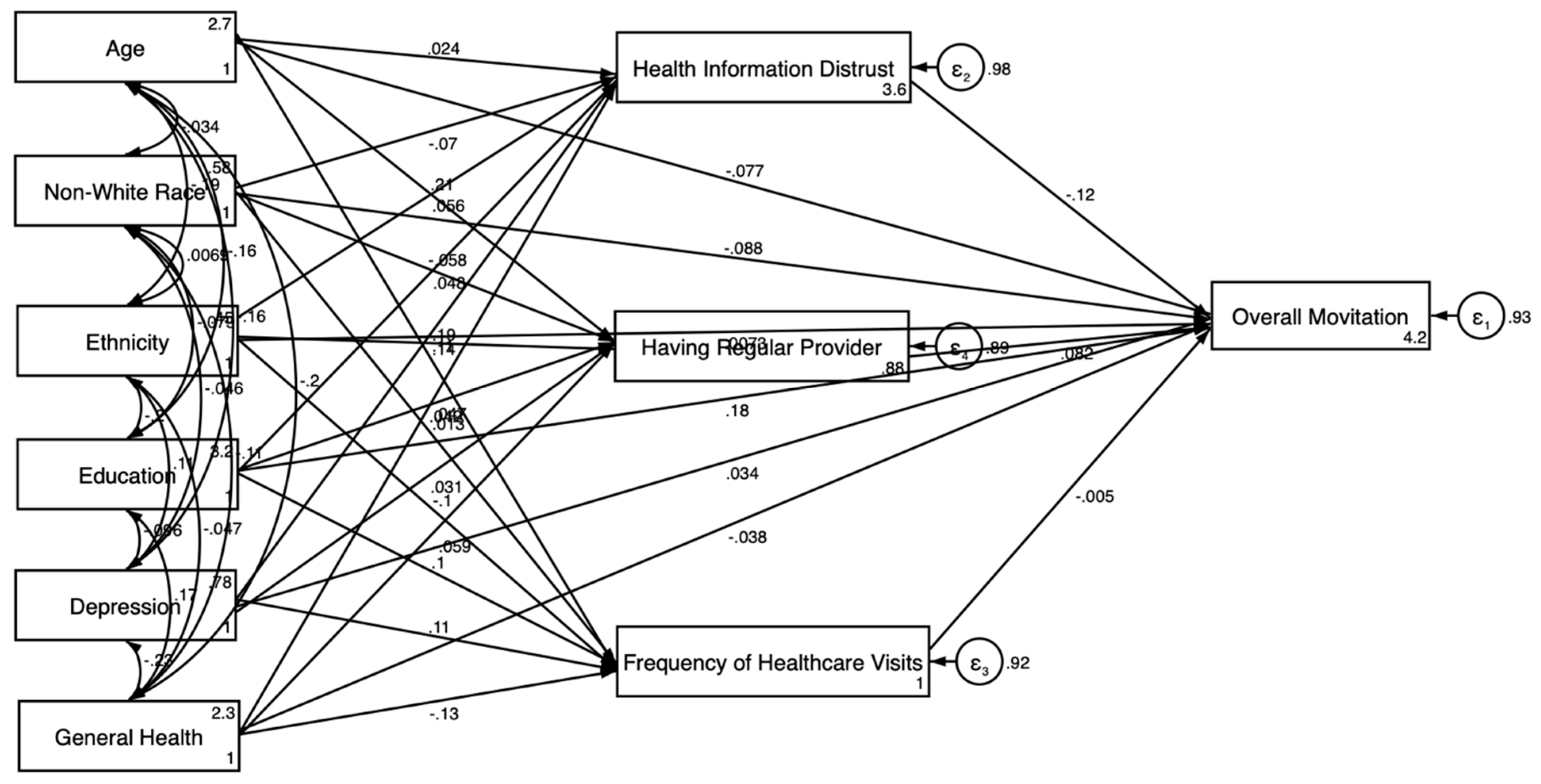

3.3.1. For Men

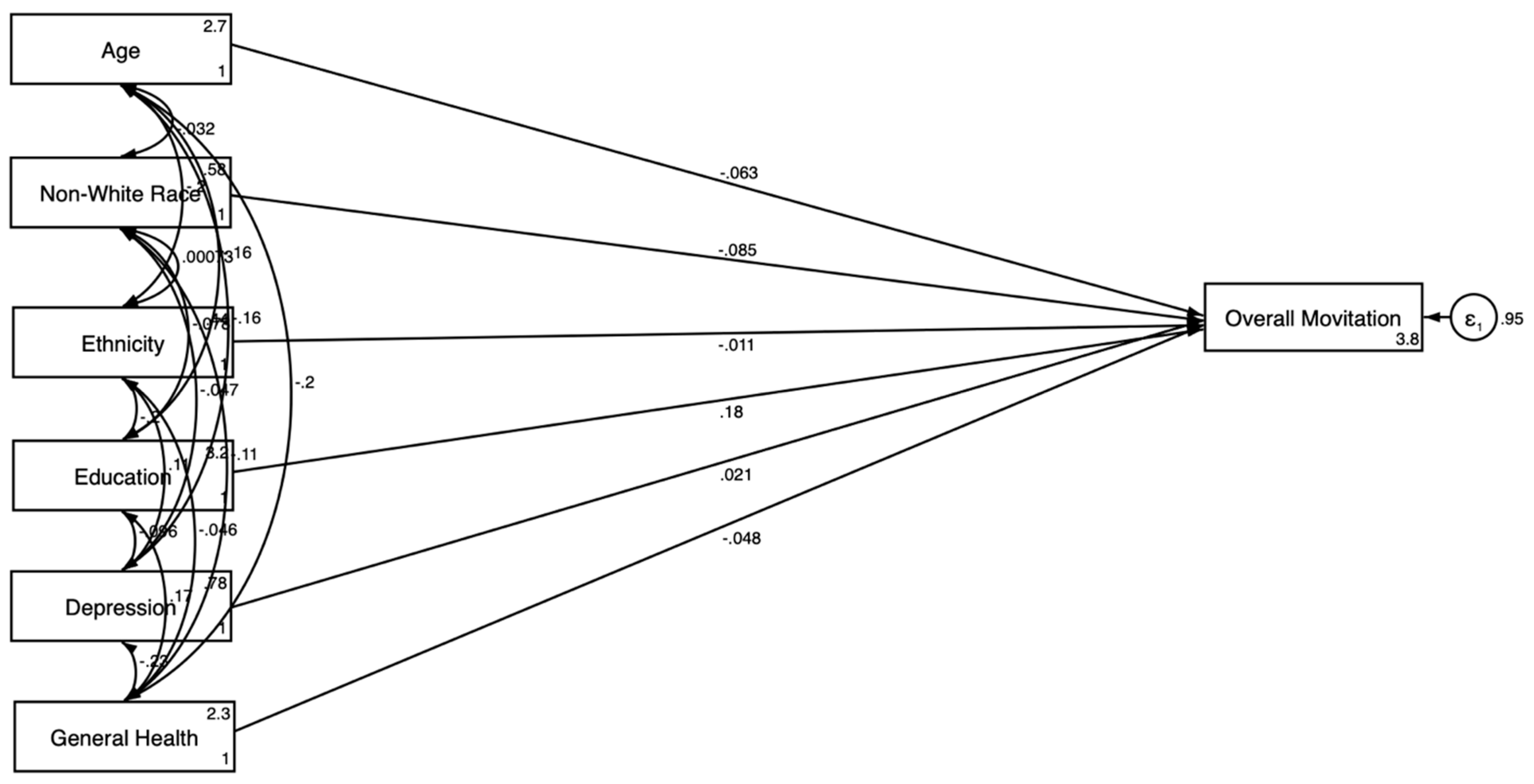

3.3.2. For Women

3.4. Results of SEMs’ Fit Statistics

4. Discussion

4.1. Healthcare Relations Explanatory Variables

4.2. Gender Differences

4.3. Implications for Policies and Programs

4.4. Implications for Future Research

4.5. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Overall Sample | Stratified Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Outcome: Motivation for Clinical Trial Participation | ||||||

| Age | −0.167 *** | 0.037 | −0.271 *** | 0.044 | −0.075 | 0.052 |

| Gender (Women) | 0.008 | 0.029 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Race (Non-White) | −0.079 ** | 0.027 | −0.069 | 0.035 | −0.088 * | 0.038 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | −0.051 | 0.031 | −0.101 * | 0.043 | 0.010 | 0.045 |

| Education | 0.120 | 0.030 | 0.060 | 0.043 | 0.181 *** | 0.043 |

| General Health Condition | −0.052 * | 0.026 | −0.045 | 0.040 | −0.038 | 0.033 |

| Depression | 0.053 | 0.031 | 0.052 | 0.043 | 0.043 | 0.039 |

| Health Information Distrust | −0.085 ** | 0.028 | −0.043 | 0.043 | −0.115 ** | 0.034 |

| Having a Regular Provider | 0.085 ** | 0.028 | 0.117 ** | 0.041 | 0.081 | 0.043 |

| Frequency of Healthcare Visits (past 12 months) | 0.016 | 0.028 | 0.046 | 0.038 | −0.005 | 0.040 |

| Quality of Care | 0.029 | 0.040 | 0.050 | 0.053 | 0.021 | 0.048 |

| Confidence in Obtaining Health Information | −0.022 | 0.031 | −0.018 | 0.047 | −0.037 | 0.040 |

| Communication with Health Professionals | −0.050 | 0.033 | −0.038 | 0.050 | −0.048 | 0.054 |

| Outcome: Health Information Distrust | ||||||

| Age | 0.017 | 0.036 | 0.018 | 0.052 | 0.024 | 0.041 |

| Gender (Women) | −0.073 * | 0.030 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Race (Non-White) | −0.060 | 0.034 | −0.058 | 0.045 | −0.070 | 0.044 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | −0.028 | 0.033 | −0.109 * | 0.048 | 0.056 | 0.041 |

| Education | 0.010 | 0.036 | −0.036 | 0.061 | 0.048 | 0.033 |

| General Health Condition | −0.004 | 0.031 | −0.065 | 0.042 | 0.047 | 0.044 |

| Depression | 0.084 ** | 0.032 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.107 ** | 0.039 |

| Outcome: Having Regular Provider | ||||||

| Age | 0.286 *** | 0.031 | 0.350 *** | 0.041 | 0.213 *** | 0.043 |

| Gender (Women) | 0.030 | 0.031 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Race (Non-White) | −0.070 | 0.033 | −0.071 | 0.054 | −0.058 | 0.035 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | −0.121 * | 0.035 | −0.056 | 0.057 | −0.187 *** | 0.043 |

| Education | 0.077 ** | 0.025 | 0.108 ** | 0.040 | 0.042 | 0.033 |

| General Health Condition | −0.041 | 0.026 | −0.029 | 0.047 | −0.059 | 0.033 |

| Depression | 0.024 | 0.026 | 0.015 | 0.047 | 0.031 | 0.034 |

| Outcome: Frequency of Healthcare Visits (Past 12 months) | ||||||

| Age | 0.217 *** | 0.027 | 0.306 *** | 0.038 | 0.139 ** | 0.040 |

| Gender (Women) | 0.064 ** | 0.022 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Race (Non-White) | −0.008 | 0.029 | −0.041 | 0.042 | 0.013 | 0.038 |

| Ethnicity | −0.083 ** | 0.031 | −0.054 | 0.041 | −0.103 * | 0.042 |

| Education | 0.128 *** | 0.025 | 0.138 *** | 0.035 | 0.104 ** | 0.035 |

| General Health Condition | −0.143 *** | 0.030 | −0.165 ** | 0.051 | −0.134 ** | 0.038 |

| Depression | 0.161 *** | 0.027 | 0.223 *** | 0.047 | 0.110 ** | 0.031 |

| Quality of Care | ||||||

| Age | −0.100 ** | 0.034 | −0.102 | 0.064 | −0.083 | 0.043 |

| Gender (Women) | −0.055 | 0.031 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Race (Non-White) | 0.039 | 0.034 | 0.019 | 0.058 | 0.052 | 0.039 |

| Ethnicity | 0.091 ** | 0.032 | 0.106 | 0.055 | 0.089 * | 0.039 |

| Education | −0.066 | 0.036 | −0.067 | 0.056 | −0.060 | 0.040 |

| General Health Condition | −0.152 *** | 0.032 | −0.171 ** | 0.059 | −0.148 *** | 0.041 |

| Depression | 0.120 ** | 0.036 | 0.196 ** | 0.064 | 0.062 | 0.035 |

| Confidence in Obtaining Health Information | ||||||

| Age | 0.018 | 0.037 | −0.011 | 0.054 | 0.063 | 0.039 |

| Gender (Women) | −0.059 | 0.031 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Race (Non-White) | 0.015 | 0.031 | −0.000 | 0.051 | 0.025 | 0.034 |

| Ethnicity | 0.032 | 0.039 | 0.011 | 0.065 | 0.047 | 0.041 |

| Education | −0.091 * | 0.039 | −0.134 * | 0.058 | −0.051 | 0.035 |

| General Health Condition | −0.004 | 0.022 | −0.013 | 0.040 | 0.020 | 0.031 |

| Depression | 0.151 *** | 0.030 | 0.158 *** | 0.044 | 0.154 *** | 0.037 |

| Communication with Health Professionals | ||||||

| Age | −0.030 | 0.041 | −0.001 | 0.067 | −0.049 | 0.045 |

| Gender (Women) | −0.028 | 0.032 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Race (Non-White) | 0.003 | 0.033 | 0.010 | 0.053 | −0.010 | 0.037 |

| Ethnicity | 0.065 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.069 | 0.080 | 0.041 |

| Education | 0.046 | 0.036 | 0.041 | 0.058 | 0.046 | 0.044 |

| General Health Condition | −0.068 * | 0.028 | −0.069 | 0.047 | −0.077 | 0.040 |

| Depression | 0.169 *** | 0.031 | 0.221 *** | 0.049 | 0.117 ** | 0.038 |

| Models | Coefficient of Determination |

|---|---|

| Overall Sample | |

| SEM in the Overall Sample without Explanatory Variables | 0.050 |

| SEM in the Overall Sample with Explanatory Variables | 0.285 |

| SEM by Gender | |

| SEM by Gender without Explanatory Variables | 0.055 |

| SEM by Gender with Explanatory Variables | 0.286 |

References

- van der Graaf, R.; van der Zande, I.S.E.; den Ruijter, H.M.; Oudijk, M.A.; van Delden, J.J.M.; Oude Rengerink, K.; Groenwold, R.H.H. Fair inclusion of pregnant women in clinical trials: An integrated scientific and ethical approach. Trials 2018, 19, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kons, K.M.; Wood, M.L.; Peck, L.C.; Hershberger, S.M.; Kunselman, A.R.; Stetter, C.; Legro, R.S.; Deimling, T.A. Exclusion of Reproductive-aged Women in COVID-19 Vaccination and Clinical Trials. Women’s Health Issues 2022, 32, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain-Gambles, M. Ethnic minority under-representation in clinical trials. Whose responsibility is it anyway? J. Health Organ. Manag. 2003, 17, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, K.; Patel, D.; Kaur, R. Assessing Multiple Factors Affecting Minority Participation in Clinical Trials: Development of the Clinical Trials Participation Barriers Survey. Cureus 2022, 14, e24424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.; Mulvagh, S.L.; Merz, C.N.; Buring, J.E.; Manson, J.E. Cardiovascular Disease in Women: Clinical Perspectives. Circ Res 2016, 118, 1273–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baca, E.; Garcia-Garcia, M.; Porras-Chavarino, A. Gender differences in treatment response to sertraline versus imipramine in patients with nonmelancholic depressive disorders. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 28, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornstein, S.G.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Thase, M.E.; Yonkers, K.A.; McCullough, J.P.; Keitner, G.I.; Gelenberg, A.J.; Davis, S.M.; Harrison, W.M.; Keller, M.B. Gender differences in treatment response to sertraline versus imipramine in chronic depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Diversity and Inclusion in Clinical Trials; National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations—Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs Guidance for Industry; US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups; Bibbins-Domingo, K., Helman, A., Eds.; The National Academies Collection: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration. 2020 Drug Trials Snapshots: Summary Report; US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.S.; Shahid, I.; Siddiqi, T.J.; Khan, S.U.; Warraich, H.J.; Greene, S.J.; Butler, J.; Michos, E.D. Ten-Year Trends in Enrollment of Women and Minorities in Pivotal Trials Supporting Recent US Food and Drug Administration Approval of Novel Cardiometabolic Drugs. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labots, G.; Jones, A.; de Visser, S.J.; Rissmann, R.; Burggraaf, J. Gender differences in clinical registration trials: Is there a real problem? Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasi, J.K.; Capili, B.; Norton, M.; McMahon, D.J.; Marder, K. Recruitment and retention of clinical trial participants: Understanding motivations of patients with chronic pain and other populations. Front. Pain Res. 2023, 4, 1330937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soule, M.C.; Beale, E.E.; Suarez, L.; Beach, S.R.; Mastromauro, C.A.; Celano, C.M.; Moore, S.V.; Huffman, J.C. Understanding motivations to participate in an observational research study: Why do patients enroll? Soc. Work Health Care 2016, 55, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.M.; Ong, W.Y.; Tan, J.; Ding, J.; Ho, S.; Tan, D.; Neo, P. Motivations and experiences of patients with advanced cancer participating in Phase 1 clinical trials: A qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 2023, 37, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nappo, S.A.; Iafrate, G.B.; Sanchez, Z.M. Motives for participating in a clinical research trial: A pilot study in Brazil. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, J.M.; Cook, E.; Tai, E.; Bleyer, A. The Role of Clinical Trial Participation in Cancer Research: Barriers, Evidence, and Strategies. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2016, 35, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjan, S.J.; Wenzel, J.A.; Martin, M.Y.; Fouad, M.N.; Vickers, S.M.; Konety, B.R.; Durant, R.W. Perceived Institutional Barriers Among Clinical and Research Professionals: Minority Participation in Oncology Clinical Trials. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, e666–e675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharff, D.P.; Mathews, K.J.; Jackson, P.; Hoffsuemmer, J.; Martin, E.; Edwards, D. More than Tuskegee: Understanding mistrust about research participation. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2010, 21, 879–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, H. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Insurance Coverage: Dynamics of Gaining and Losing Coverage over the Life-Course. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2017, 36, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Duran, N.; Norris, K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e16–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmotzer, G.L. Barriers and facilitators to participation of minorities in clinical trials. Ethn. Dis. 2012, 22, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Donzo, M.W.; Nguyen, G.; Nemeth, J.K.; Owoc, M.S.; Mady, L.J.; Chen, A.Y.; Schmitt, N.C. Effects of socioeconomic status on enrollment in clinical trials for cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedinsewo, D.; Eberly, L.; Sokumbi, O.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Patten, C.A.; Brewer, L.C. Health Disparities, Clinical Trials, and the Digital Divide. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2023, 98, 1875–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, T.C.; Arnold, C.L.; Mills, G.; Miele, L. A Qualitative Study Exploring Barriers and Facilitators of Enrolling Underrepresented Populations in Clinical Trials and Biobanking. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, G.; Chaudhary, P.; Quinn, A.; Su, D. Barriers for cancer clinical trial enrollment: A qualitative study of the perspectives of healthcare providers. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2022, 28, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlon, J.K.; Wofford, L.; Fair, A.; Philippi, D. Predictors of Participation in Clinical Research. Nurs. Res. 2021, 70, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurt, A.; Kincaid, H.M.; Curtis, C.; Semler, L.; Meyers, M.; Johnson, M.; Careyva, B.A.; Stello, B.; Friel, T.J.; Knouse, M.C.; et al. Factors Influencing Participation in Clinical Trials: Emergency Medicine vs. Other Specialties. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 18, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaiser, K.; Rauscher, G.H.; Jacobs, E.A.; Strenski, T.A.; Ferrans, C.E.; Warnecke, R.B. The import of trust in regular providers to trust in cancer physicians among white, African American, and Hispanic breast cancer patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Health Information National Trends Survey 5 (HINTS 5) Cycle 4 Methodology Report; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approvals for the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS); National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, D.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. The Effect of Estimation Methods on SEM Fit Indices. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2020, 80, 421–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tustumi, F. Choosing the most appropriate cut-point for continuous variables. Rev. Col. Bras. Cir. 2022, 49, e20223346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Zhang, S.; Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraballo, C.; Massey, D.; Mahajan, S.; Lu, Y.; Annapureddy, A.R.; Roy, B.; Riley, C.; Murugiah, K.; Valero-Elizondo, J.; Onuma, O.; et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Health Care Among Adults in the United States: A 20-Year National Health Interview Survey Analysis, 1999–2018. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias-Konstantopoulos, W.L.; Collins, K.A.; Diaz, R.; Duber, H.C.; Edwards, C.D.; Hsu, A.P.; Ranney, M.L.; Riviello, R.J.; Wettstein, Z.S.; Sachs, C.J. Race, Healthcare, and Health Disparities: A Critical Review and Recommendations for Advancing Health Equity. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 24, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.; Lowe, B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010, 32, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, B.; Wahl, I.; Rose, M.; Spitzer, C.; Glaesmer, H.; Wingenfeld, K.; Schneider, A.; Brahler, E. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 122, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzrago, D.; Walker, T.J.; Williams, F. Reliability and validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 scale and its subscales of depression and anxiety among US adults based on nativity. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.M.; Gin, L.E.; Barnes, M.E.; Brownell, S.E. An Exploratory Study of Students with Depression in Undergraduate Research Experiences. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2020, 19, ar19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, C.S.; Niedermeier, M.; Gufler, A.; Galffy, M.; Sperner-Unterweger, B.; Kopp, M. A case-control study on physical activity preferences, motives, and barriers in patients with psychiatric conditions. Compr. Psychiatry 2021, 111, 152276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunzler, D.; Chen, T.; Wu, P.; Zhang, H. Introduction to mediation analysis with structural equation modeling. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2013, 25, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepho, H.P. An adjusted coefficient of determination (R2) for generalized linear mixed models in one go. Biom. J. 2023, 65, e2200290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schminkey, D.L.; von Oertzen, T.; Bullock, L. Handling Missing Data With Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling and Full Information Maximum Likelihood Techniques. Res. Nurs. Health 2016, 39, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, D.M.; Jaeger, E.C.; Bergner, E.M.; Stallings, S.; Wilkins, C.H. Determinants of Trustworthiness to Conduct Medical Research: Findings from Focus Groups Conducted with Racially and Ethnically Diverse Adults. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 2969–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, K.; Nosova, E.; DeBeck, K.; Hayashi, K.; Milloy, M.J.; Richardson, L. Trust in research physicians as a key dimension of randomized controlled trial participation in clinical addictions research. Subst. Abus. 2021, 42, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, A.C.; Green, D.C.; Davis, N.A.; Koplan, J.P.; Cleary, P.D. Patients’ trust in their physicians: Effects of choice, continuity, and payment method. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1998, 13, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.J.; Gassman-Pines, A.; Boucher, N.A. Insurance Barriers, Gendering, and Access: Interviews with Central North Carolinian Women About Their Health Care Experiences. Perm. J. 2021, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra-Gupta, S.; Petruzzi, L.; Jones, C.; Cubbin, C. An Intersectional Approach to Understanding Barriers to Healthcare for Women. J. Community Health 2023, 48, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samulowitz, A.; Gremyr, I.; Eriksson, E.; Hensing, G. “Brave Men” and “Emotional Women”: A Theory-Guided Literature Review on Gender Bias in Health Care and Gendered Norms towards Patients with Chronic Pain. Pain Res. Manag. 2018, 2018, 6358624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, P.; Ganguly, A.P.; Kuo, M.; Martin, R.; Alvarez, K.S.; Bhavan, K.P.; Kho, K.A. Childcare needs as a barrier to healthcare among women in a safety-net health system. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.R.; Crooks, D.; Ellis, P.M.; Mings, D.; Whelan, T.J. Factors that influence the recruitment of patients to Phase III studies in oncology: The perspective of the clinical research associate. Cancer 2002, 95, 1584–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouton, C.P.; Harris, S.; Rovi, S.; Solorzano, P.; Johnson, M.S. Barriers to black women’s participation in cancer clinical trials. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 1997, 89, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sutton, A.L.; He, J.; Tanner, E.; Edmonds, M.C.; Henderson, A.; Hurtado de Mendoza, A.; Sheppard, V.B. Understanding Medical Mistrust in Black Women at Risk of BRCA 1/2 Mutations. J. Health Dispar. Res. Pract. 2019, 12, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galea, S.; Tracy, M. Participation Rates in Epidemiologic Studies. Ann. Epidemiol. 2007, 17, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattis, J.S.; Hammond, W.P.; Grayman, N.; Bonacci, M.; Brennan, W.; Cowie, S.A.; Ladyzhenskaya, L.; So, S. The social production of altruism: Motivations for caring action in a low-income urban community. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 43, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, J.R.; Wells, C.K.; Viscoli, C.M.; Brass, L.M.; Kernan, W.N.; Horwitz, R.I. Altruism as a reason for participation in clinical trials was independently associated with adherence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzeczkowska, A.; Spalding, D.M.; McGeown, W.J.; Gow, A.J.; Carlson, M.C.; Nicholls, L.A.B. A systematic review of the impacts of intergenerational engagement on older adults’ cognitive, social, and health outcomes. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 71, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, J.B.; Liu, R.Y.; Boscardin, J.; Liu, Q.; Lau, S.W.J.; Khatri, S.; Tarn, D. Attitudes on participation in clinical drug trials: A nationally representative survey of older adults with multimorbidity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brathwaite, J.S.; Goldstein, D.; Dowgiallo, E.; Haroun, L.; Hogue, K.A.; Arakaki, T. Barriers to Clinical Trial Enrollment: Focus on Underrepresented Populations. Clin. Res. 2024, 38, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, A.P.; Snipes, S.A.; King, D.W.; Torres-Vigil, I.; Goldberg, D.S.; Weinberg, A.D. Disparate inclusion of older adults in clinical trials: Priorities and opportunities for policy and practice change. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100 (Suppl. S1), S105–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisson, J.; Balasa, R.; Bowra, A.; Hill, D.C.; Doshi, A.S.; Tan, D.H.S.; Perez-Brumer, A. Motivations for enrollment in a COVID-19 ring-based post-exposure prophylaxis trial: Qualitative examination of participant experiences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2024, 24, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feuer, Z.; Matulewicz, R.S.; Basak, R.; Culton, D.A.; Weaver, K.; Gallagher, K.; Hung-Jui, T.; Rose, T.L.; Milowsky, M.; Bjurlin, M.A. Non-oncology clinical trial engagement in a nationally representative sample: Identification of motivators and barriers. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2022, 115, 106715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaian, H.A.; Freeman, D.J. Gender differences in self-confidence and educational beliefs among secondary teacher candidates. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1994, 10, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S. Gender Differences in Self-esteem and Self-confidence. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Personality Processes and Individual Differences; Carducci, B.J., Nave, C.S., Fabio, A.D., Saklofske, D.H., Stough, C., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitchik, M. Confidence and gender: Few differences, but gender stereotypes impact perceptions of confidence. Psychol.-Manag. J. 2020, 23, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable and Prompt | Response Coding | Analytical Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Health Information Distrust In general, how much would you trust information about cancer from each of the following?— (a) A doctor; (b) Family or friends; (c) Government Health Agencies; (d) Charitable organizations; (e) Religious organizations or leaders. | For each option:

|

|

| Having a Regular Provider Not including psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, is there a particular doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you see most often? |

|

|

| Frequency of Healthcare Visits In the past 12 months, not counting the times you went to an emergency room, how many times did you go to a doctor, nurse, or other health professional to get care for yourself? |

|

|

| Confidence in Obtaining Health Information Overall, how confident are you that you could get advice or information about cancer if you needed it? |

|

|

| Quality of Care Overall, how would you rate the quality of health care you received in the past 12 months? |

|

|

| Communication with Health Professionals How often did they do each of the following?— (a) Give you the chance to ask all of the health-related questions you had; (b) Give the attention you needed to your feelings and emotions; (c) Involve you in decisions about your health care as much as you wanted; (d) Make sure you understood the things you needed to do to take care of your health; (e) Explain things in a way you could understand; (f) Spend enough time with you; (g) Help you deal with feelings of uncertainty about your health or health care. |

|

|

| Variables | Low Motivation (Weighted n = 124,447,744) | High Motivation (Weighted n = 125,078,757) | Total (Weighted n = 253,815,197) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | 95% CI | % | SE | 95% CI | % | SE | 95% CI | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Men | 50.0 | 0.02 | 45.6–54.5 | 47.7 | 0.02 | 43.7–51.8 | 48.6 | 0.02 | 45.6–51.7 |

| Women | 50.0 | 0.02 | 45.5–54.4 | 52.3 | 0.02 | 48.2–56.3 | 51.4 | 0.02 | 48.3–54.4 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 74.2 | 0.02 | 70.5–77.5 | 77.7 | 0.01 | 74.7–80.4 | 75.7 | 0.01 | 73.5–77.8 |

| Non-White | 25.8 | 0.01 | 22.5–29.5 | 22.3 | 0.01 | 19.6–25.3 | 24.3 | 0.01 | 22.2–26.5 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 82.9 | 0.01 | 80.2–85.3 | 83.3 | 0.02 | 79.5–86.5 | 83.1 | 0.01 | 81.0–85.0 |

| Hispanic | 17.1 | 0.01 | 14.7–19.8 | 16.7 | 0.02 | 13.5–20.5 | 16.9 | 0.01 | 15.0–19.0 |

| Educational Attainment | |||||||||

| Less than High School | 11.7 | 0.01 | 9.1–15.0 | 4.2 | 0.01 | 2.9–6.1 | 8.0 | 0.01 | 6.4–10.0 |

| High School Graduate | 21.0 | 0.01 | 18.4–23.8 | 23.8 | 0.02 | 20.3–27.6 | 22.5 | 0.01 | 20.3–24.9 |

| Some College | 39.8 | 0.02 | 36.0–43.7 | 38.7 | 0.02 | 34.8–42.8 | 39.2 | 0.01 | 36.5–42.0 |

| College Graduate or More | 27.5 | 0.01 | 24.9–30.2 | 33.3 | 0.02 | 30.0–36.9 | 30.3 | 0.01 | 28.0–32.6 |

| General Health Condition | |||||||||

| Poor or Fair | 13.2 | 0.01 | 11.0–15.9 | 14.8 | 0.01 | 12.1–18.0 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 12.4–16.0 |

| Excellent, Very good, or Good | 86.8 | 0.01 | 84.1–89.0 | 85.2 | 0.01 | 82.0–87.9 | 0.86 | 0.01 | 84.0–87.6 |

| Having Regular Provider | |||||||||

| No | 41.4 | 0.02 | 37.9–45.0 | 33.9 | 0.02 | 30.0–38.0 | 37.7 | 0.01 | 35.1–40.5 |

| Yes | 58.6 | 0.02 | 55.0–62.1 | 66.1 | 0.02 | 62.0–70.0 | 62.3 | 0.01 | 59.5–64.9 |

| Frequency of Healthcare Visits (Past 12 months) | |||||||||

| None | 20.8 | 0.02 | 17.7–24.3 | 13.0 | 0.01 | 10.4–16.0 | 16.8 | 0.01 | 14.8–19.1 |

| 1 time | 15.1 | 0.01 | 12.4–18.3 | 18.7 | 0.02 | 15.3–22.5 | 16.8 | 0.01 | 14.4–19.4 |

| 2 times | 21.1 | 0.02 | 18.0–24.5 | 19.5 | 0.01 | 17.2–22.1 | 20.2 | 0.01 | 18.2–22.4 |

| 3 times | 12.1 | 0.01 | 10.2–14.3 | 14.8 | 0.01 | 12.3–17.7 | 13.4 | 0.01 | 11.8–15.1 |

| 4 times | 10.7 | 0.01 | 9.1–12.6 | 11.2 | 0.01 | 09.2–13.7 | 11.1 | 0.01 | 9.7–12.6 |

| 5–9 times | 13.0 | 0.01 | 10.6–15.9 | 14.3 | 0.01 | 12.0–17.0 | 13.7 | 0.01 | 12.0–15.7 |

| 10 or more times | 7.2 | 0.01 | 5.7–9.1 | 8.5 | 0.01 | 6.7–10.7 | 8.0 | 0.01 | 6.7–9.4 |

| Quality of Care | |||||||||

| Excellent | 29.4 | 0.02 | 25.7–33.5 | 27.7 | 0.02 | 24.5–31.1 | 28.3 | 0.01 | 25.9–30.8 |

| Very Good | 40.8 | 0.02 | 37.3–44.5 | 42.5 | 0.02 | 38.4–46.8 | 41.9 | 0.01 | 39.1–44.7 |

| Good | 23.4 | 0.02 | 19.6–27.8 | 20.9 | 0.02 | 17.6–24.6 | 22.2 | 0.01 | 19.6–25.0 |

| Fair | 5.1 | 0.01 | 3.4–7.4 | 8.3 | 0.02 | 5.4–12.4 | 6.7 | 0.01 | 5.0–8.8 |

| Poor | 1.3 | 0.00 | 0.6–2.6 | 0.6 | 0.00 | 0.4–1.2 | 01.0 | 0.00 | 0.6–1.7 |

| Confidence in Obtaining Health Information | |||||||||

| Completely Confident | 30.8 | 0.02 | 27.3–34.6 | 31.0 | 0.02 | 27.6–34.5 | 30.9 | 0.01 | 28.5–33.3 |

| Very Confident | 32.0 | 0.01 | 29.3–34.8 | 38.4 | 0.02 | 34.7–42.3 | 35.1 | 0.01 | 32.9–37.3 |

| Somewhat Confident | 28.3 | 0.02 | 25.0–31.8 | 23.7 | 0.02 | 20.8–27.0 | 26.1 | 0.01 | 24.0–28.4 |

| A Little Confident | 5.5 | 0.01 | 04.2–07.2 | 4.5 | 0.01 | 2.9–7.1 | 5.0 | 0.01 | 3.9–6.4 |

| Not Confident At All | 3.4 | 0.01 | 1.9–5.7 | 2.4 | 0.01 | 1.2–4.5 | 2.9 | 0.01 | 1.9–4.4 |

| Mean | SE | 95% CI | Mean | SE | 95% CI | Mean | SE | 95% CI | |

| Age (years) | 50.1 | 0.89 | 48.4–51.9 | 46.4 | 0.73 | 44.9–47.8 | 48.4 | 0.53 | 47.4–49.5 |

| Depression | 2.0 | 0.12 | 1.8–2.3 | 2.4 | 0.13 | 2.1–2.6 | 2.2 | 0.09 | 2.0–2.4 |

| Health Information Distrust | 2.2 | 0.02 | 2.2–2.3 | 2.2 | 0.02 | 2.1–2.2 | 2.2 | 0.02 | 2.2–2.3 |

| Communication with Health Professionals (1–4) | 1.6 | 0.03 | 1.6–1.7 | 1.6 | 0.03 | 1.6–1.7 | 1.6 | 0.02 | 1.6–1.7 |

| Variables | Model 1 Without Explanatory Variables | Model 2 With Explanatory Variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| Outcome: Motivation for Clinical Trial Participation | ||||

| Age | −0.144 *** | 0.038 | −0.170 *** | 0.038 |

| Gender (Women) | 0.017 | 0.030 | 0.008 | 0.029 |

| Race (Non-White) | −0.078 ** | 0.026 | −0.078 ** | 0.027 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | −0.059 | 0.031 | −0.051 | 0.032 |

| Education | 0.125 *** | 0.029 | 0.117 *** | 0.029 |

| General Health Condition | −0.058 * | 0.026 | −0.053 * | 0.026 |

| Depression | 0.042 | 0.031 | 0.046 | 0.031 |

| Health Information Distrust | NA | NA | −0.094 ** | 0.028 |

| Having a Regular Provider | NA | NA | 0.087 ** | 0.028 |

| Frequency of Healthcare Visits (past 12 months) | NA | NA | 0.014 | 0.029 |

| Outcome: Health Information Distrust | ||||

| Age | NA | NA | 0.017 | 0.036 |

| Gender (Women) | NA | NA | −0.073 * | 0.030 |

| Race (Non-White) | NA | NA | −0.060 | 0.034 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | NA | NA | −0.028 | 0.033 |

| Education | NA | NA | 0.010 | 0.036 |

| General Health Condition | NA | NA | −0.004 | 0.031 |

| Depression | NA | NA | 0.084 ** | 0.032 |

| Outcome: Having Regular Provider | ||||

| Age | NA | NA | 0.286 *** | 0.031 |

| Gender (Women) | NA | NA | 0.030 | 0.031 |

| Race (Non-White) | −0.070 | 0.033 | ||

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | NA | NA | −0.121 * | 0.035 |

| Education | NA | NA | 0.077 ** | 0.025 |

| General Health Condition | NA | NA | −0.041 | 0.026 |

| Depression | NA | NA | 0.024 | 0.026 |

| Outcome: Frequency of Healthcare Visits (Past 12 months) | ||||

| Age | NA | NA | 0.217 *** | 0.027 |

| Gender (Women) | NA | NA | 0.064 ** | 0.022 |

| Race (Non-White) | −0.008 | 0.029 | ||

| Ethnicity | NA | NA | −0.083 ** | 0.031 |

| Education | NA | NA | 0.128 *** | 0.025 |

| General Health Condition | NA | NA | −0.143 *** | 0.030 |

| Depression | NA | NA | 0.161 *** | 0.027 |

| Variables | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3 Without Explanatory Variables | Model 4 With Explanatory Variables | Model 5 Without Explanatory Variables | Model 6 With Explanatory Variables | |||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| Outcome: Motivation for Clinical Trial Participation | ||||||||

| Age | −0.219 *** | 0.046 | −0.275 *** | 0.045 | −0.063 | 0.055 | −0.076 | 0.052 |

| Race (Non-White) | −0.073 * | 0.036 | −0.068 | 0.035 | −0.085 * | 0.037 | −0.087 * | 0.039 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | −0.099 * | 0.042 | −0.099 * | 0.042 | −0.011 | 0.044 | 0.007 | 0.045 |

| Education | 0.077 | 0.044 | 0.057 | 0.043 | 0.175 *** | 0.042 | 0.178 *** | 0.042 |

| General Health Condition | −0.056 | 0.039 | −0.051 | 0.039 | −0.048 | 0.033 | −0.038 | 0.033 |

| Depression | 0.064 | 0.041 | 0.052 | 0.042 | 0.021 | 0.042 | 0.034 | 0.040 |

| Health Information Distrust | NA | NA | −0.047 | 0.042 | NA | NA | −0.125 ** | 0.037 |

| Having a Regular Provider | NA | NA | 0.116 ** | 0.041 | NA | NA | 0.082 | 0.043 |

| Frequency of Healthcare Visits (past 12 months) | NA | NA | 0.043 | 0.039 | NA | NA | −0.005 | 0.040 |

| Outcome: Health Information Distrust | ||||||||

| Age | NA | NA | 0.018 | 0.052 | NA | NA | 0.024 | 0.041 |

| Race (Non-White) | NA | NA | −0.058 | 0.045 | NA | NA | −0.070 | 0.044 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | NA | NA | −0.109 * | 0.048 | NA | NA | 0.056 | 0.041 |

| Education | NA | NA | −0.036 | 0.061 | NA | NA | 0.048 | 0.033 |

| General Health Condition | NA | NA | −0.065 | 0.042 | NA | NA | 0.047 | 0.044 |

| Depression | NA | NA | 0.049 | 0.048 | NA | NA | 0.107 ** | 0.039 |

| Outcome: Having Regular Provider | ||||||||

| Age | NA | NA | 0.350 *** | 0.041 | NA | NA | 0.213 *** | 0.043 |

| Race (Non-White) | NA | NA | −0.071 | 0.054 | NA | NA | −0.058 | 0.035 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | NA | NA | −0.056 | 0.057 | NA | NA | −0.187 *** | 0.043 |

| Education | NA | NA | 0.108 ** | 0.040 | NA | NA | 0.042 | 0.033 |

| General Health Condition | NA | NA | −0.029 | 0.047 | NA | NA | −0.059 | 0.033 |

| Depression | NA | NA | 0.015 | 0.047 | NA | NA | 0.031 | 0.034 |

| Outcome: Frequency of Healthcare Visits (Past 12 months) | ||||||||

| Age | NA | NA | 0.306 *** | 0.038 | NA | NA | 0.139 ** | 0.040 |

| Race (Non-White) | NA | NA | −0.041 | 0.042 | NA | NA | 0.013 | 0.038 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | NA | NA | −0.054 | 0.041 | NA | NA | −0.103 * | 0.042 |

| Education | NA | NA | 0.138 *** | 0.035 | NA | NA | 0.104 ** | 0.035 |

| General Health Condition | NA | NA | −0.165 ** | 0.051 | NA | NA | −0.134 ** | 0.038 |

| Depression | NA | NA | 0.223 *** | 0.047 | NA | NA | 0.110 ** | 0.031 |

| Variables | Overall Sample | Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Explanatory Variables | With Explanatory Variables | Without Explanatory Variables | With Explanatory Variables | Without Explanatory Variables | With Explanatory Variables | |

| Age | - | - | - | - | NS | NS |

| Non-White Race | - | - | - | NS | - | - |

| Education | + | + | NS | NS | + | + |

| Health Information Distrust | NA | - | NA | NS | NA | - |

| Having a Regular Healthcare Provider | NA | + | NA | + | NA | NS |

| Frequency of Healthcare Visits | NA | NS | NA | NS | NA | NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barsha, R.A.A.; Assari, S.; Byiringiro, S.; Michos, E.D.; Plante, T.B.; Miller, H.N.; Himmelfarb, C.R.; Sheikhattari, P. Motivation to Clinical Trial Participation: Health Information Distrust and Healthcare Access as Explanatory Variables and Gender as Moderator. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020485

Barsha RAA, Assari S, Byiringiro S, Michos ED, Plante TB, Miller HN, Himmelfarb CR, Sheikhattari P. Motivation to Clinical Trial Participation: Health Information Distrust and Healthcare Access as Explanatory Variables and Gender as Moderator. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(2):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020485

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarsha, Rifath Ara Alam, Shervin Assari, Samuel Byiringiro, Erin D. Michos, Timothy B. Plante, Hailey N. Miller, Cheryl R. Himmelfarb, and Payam Sheikhattari. 2025. "Motivation to Clinical Trial Participation: Health Information Distrust and Healthcare Access as Explanatory Variables and Gender as Moderator" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 2: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020485

APA StyleBarsha, R. A. A., Assari, S., Byiringiro, S., Michos, E. D., Plante, T. B., Miller, H. N., Himmelfarb, C. R., & Sheikhattari, P. (2025). Motivation to Clinical Trial Participation: Health Information Distrust and Healthcare Access as Explanatory Variables and Gender as Moderator. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020485