Social Vulnerability and Pregnancy Option Counseling in the Setting of Periviable Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

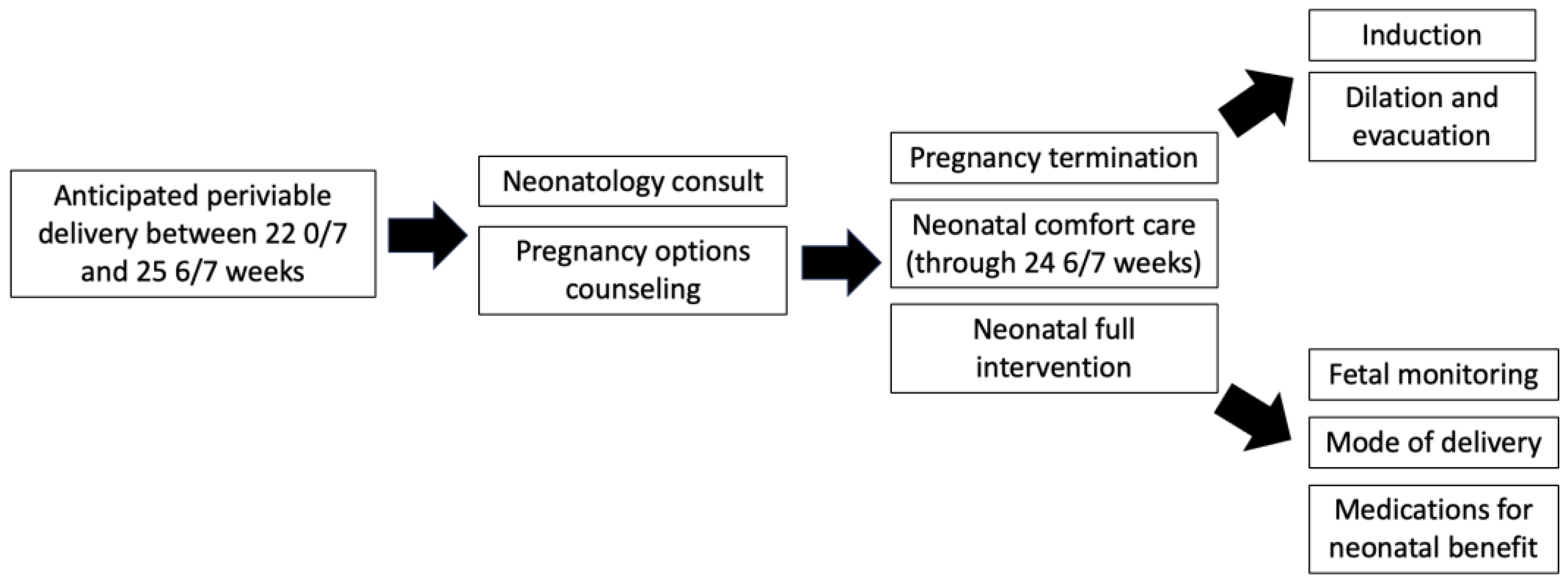

2. Materials and Methods

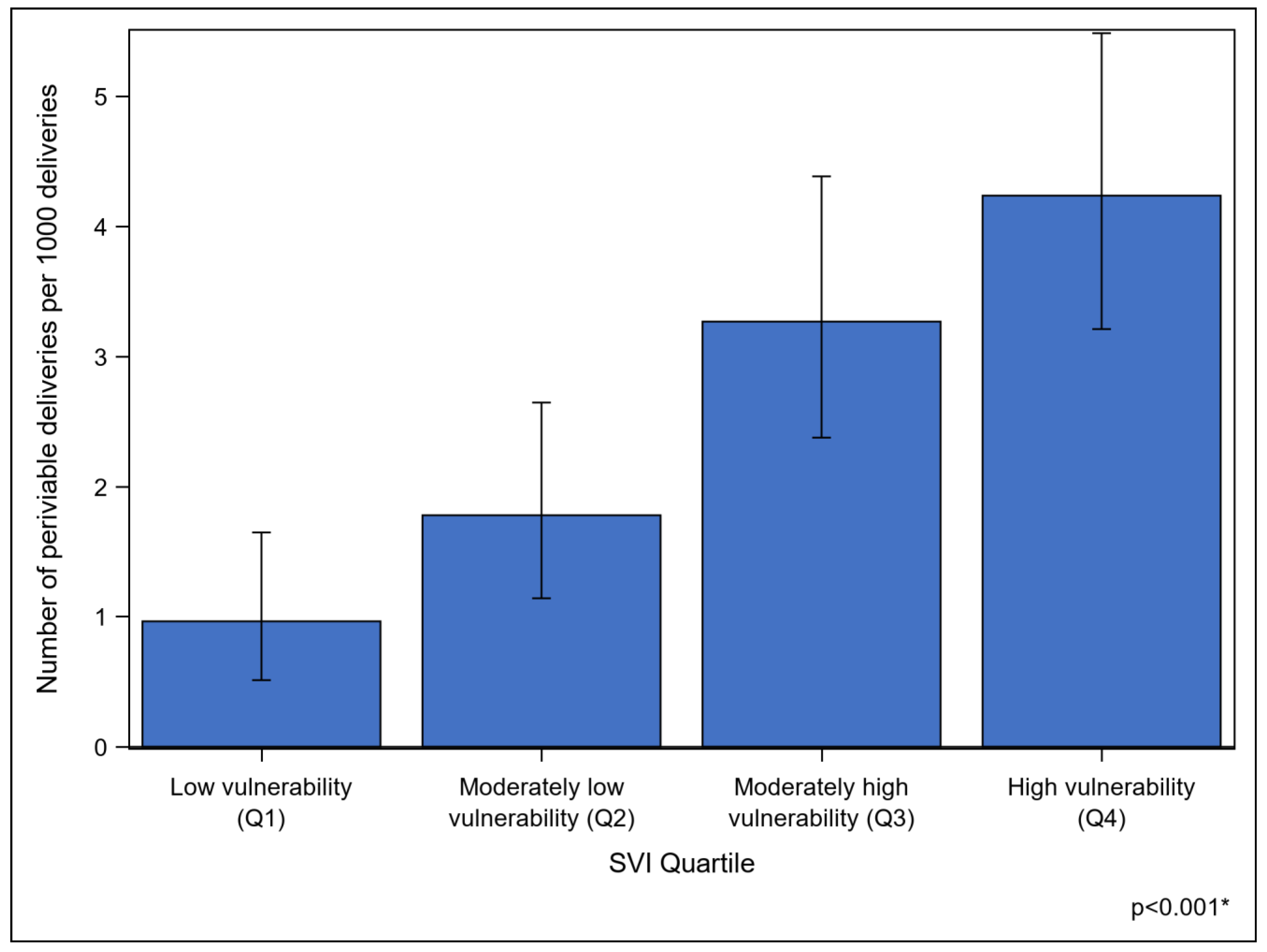

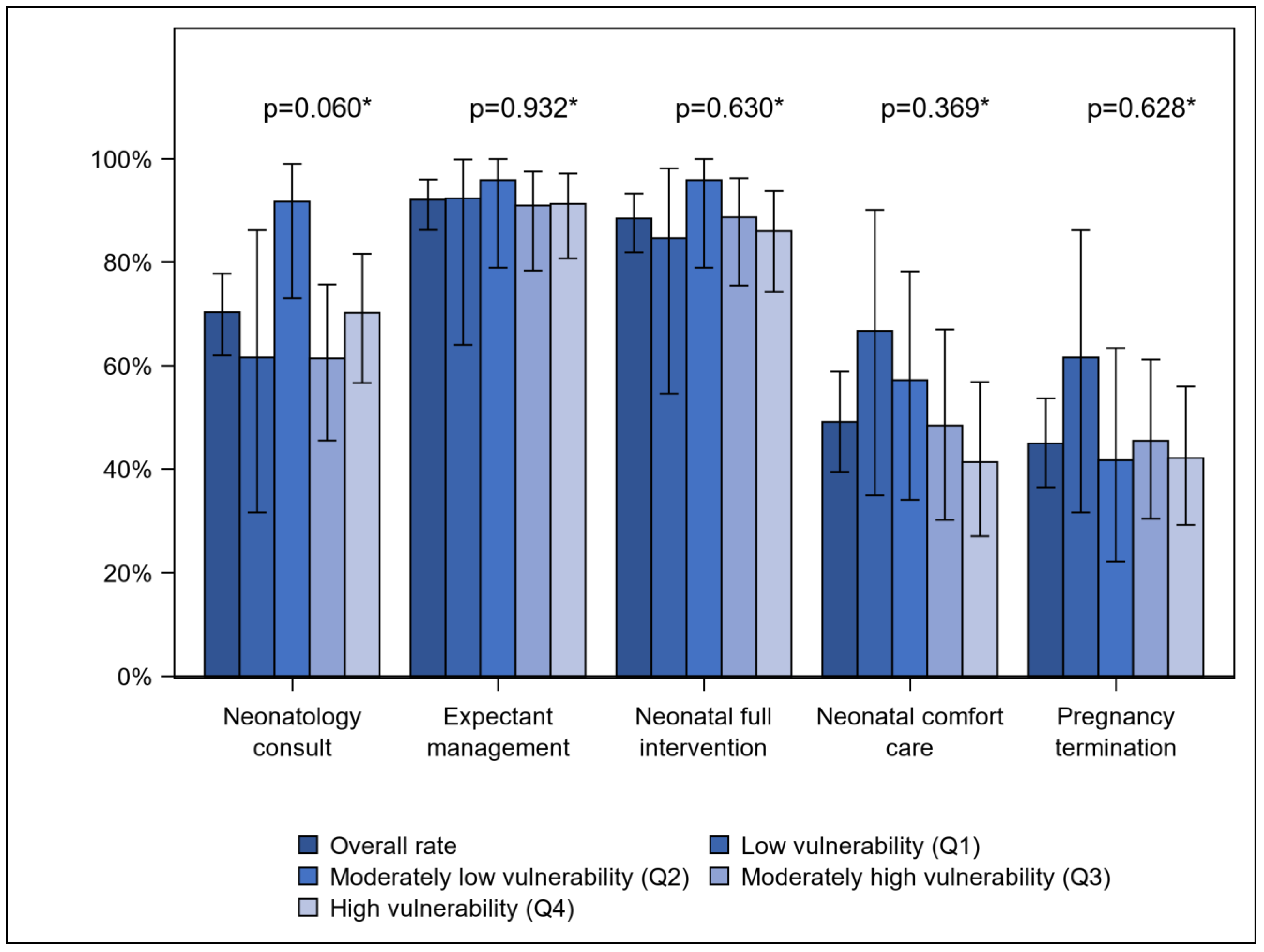

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raju, T.N.K.; Mercer, B.M.; Burchfield, D.J.; Joseph, G.F., Jr. Periviable birth: Executive summary of a joint workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Battarbee, A.N.; Osmundson, S.O.; McCarthy, A.M.; Louis, J.L.; SMFM Publications Committee. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consults Series #71: Management of previable and periviable preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 231, B2–B15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stoll, B.J.; Hansen, N.I.; Bell, E.F.; Shankaran, S.; Laptook, A.R.; Walsh, M.C.; Hale, E.C.; Newman, N.S.; Schibler, K.; Carlo, W.A.; et al. Neonatal Outcomes of Extremely Preterm Infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2010, 126, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seasely, A.R.; Jauk, V.C.; Szyvhowski, J.M.; Ambalavanan, N.; Tita, A.T.; Casey, B.M. Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes at Periviable Gestation throughout Delivery Admission. Am. J. Perinatol. 2024, 41, e2952–e2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysavy, M.A.; Li, L.; Bell, E.F.; Das, A.; Hintz, S.R.; Stoll, B.J.; Vohr, B.R.; Carlo, W.A.; Shankaran, S.; Walsh, M.C.; et al. Between-Hospital Variation in Treatment and Outcomes in Extremely Preterm Infants. N. Eng. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.M.; DeFranco, E.A. Maternal Complications Associated with Periviable Birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagano, M.P.; Fofah, O.; Apuzzio, J.J.; Williams, S.F.; Gittens-Williams, L. Maternal morbidity after early preterm delivery (23–28 weeks). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2020, 2, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Committee on Fetus Newborn Watterberg, K.; Eichenwald, E.; Poindexter, B.; Stewart, D.L.; Aucott, S.W.; Puopolo, K.M.; Goldsmith, J.P. Antenatal Counseling Regarding Resuscitation and Intensive Care Before 25 Weeks of Gestation. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birth, P. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 130, e187–e199. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker Edmonds, B.; McKenzie, F.; Panoch, J.E.; Barnato, A.E.; Frankel, R.M. Comapring Obstetricians’ and Neonatologists’ Approaches to Periviable Counseling. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorch, S.A.; Enlow, E. The role of social determinants in explaining racial/ethnic disparities in perinatal outcomes. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 79, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crequit, S.; Chatzistergiou, K.; Bierry, G.; Bouali, S.; La Tour, A.D.; Sgihouar, N.; Renevier, B. Association between social vulnerability profiles, prenatal care use and pregnancy outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Givens, M.; Teal, E.N.; Patel, V.; Manuck, T.A. Preterm birth among pregnant women living in areas with high social vulnerability. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2021, 3, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, E.G.; Montoya-Williams, D.; Passarella, M.; McGann, C.; Paul, K.; Murosko, D.; Peña, M.M.; Ortiz, R.; Burris, H.H.; Lorch, S.A.; et al. County-Level Maternal Vulnerability and Preterm Birth in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2315306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Updated 14 June 2024. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/place-health/php/svi/index.html (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Marcello, K.R.; Stefano, J.L.; Lampron, K.; Barrington, K.J.; Mackley, A.B.; Janvier, A. The Influence of Family Characteristics on Perinatal Decision Making. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e934–e939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, M.D.; Downs, S.M.; Tucker Edmonds, B. Influence of Maternal Factors in Neonatologists’ Counseling for Periviable Pregnancies. Am. J. Perinatol. 2017, 34, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, B.T.; McKenzie, F.; Fadel, W.F.; Matthias, M.S.; Salyers, M.P.; Barnato, A.E.; Frankel, R.M. Using Simulation to Assess the Influence of Race and Insurer on Shared Decision-making in Periviable Counseling. Simul. Healthc. 2014, 9, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker Edmonds, B.; Fager, C.; Srinivas, S.; Lorch, S. Racial and ethnic differences in use of intubation for periviable neonates. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e1120–e1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, K.K.; Lynch, C.D.; Costantine, M.M. Trends in Active Treatment of Live-born Neonates Between 22 Weeks 0 Days and 25 Weeks 6 Days by Gestational Age and Maternal Race and Ethnicity in the US, 2014 to 2020. JAMA 2022, 328, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, K.L.; Church, A.; Hempel, B.; Yuan, H.; Goold, S.D.; Freed, G.L. End-of-life choices for African-American and white infants in a neonatal intensive-care unit: A pilot study. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2004, 96, 933–937. [Google Scholar]

- Boghossian, N.S.; Geraci, M.; Edwards, E.M.; Ehret, D.E.Y.; Saade, G.R.; Horbar, J.D. Regional and Racial-Ethnic Differences in Perinatal Interventions Among Periviable Births. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horbar, J.D.; Edwards, E.M.; Greenberg, L.T.; Profit, J.; Draper, D.; Helkey, D.; Lorch, S.A.; Lee, H.C.; Phibbs, C.S.; Rogowski, J.; et al. Racial Segregations and Inequality in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unity for Very Low-Birth-Weight and Very Preterm Infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, E.A.; Janevic, T.; Herbert, P.L.; Egorova, N.N.; Balbierz, A.; Zeitlin, J. Differences in Morbidity and Mortality Rates in Black, White, and Hispanic Very Preterm Infants Among New York City Hospitals. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, R.; Keene, D.E.; Kershaw, T.S.; Ickovics, J.R.; Warren, J.L. Racial and ethnic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: Differences by racial residential segregation. SSM Popul. Health 2019, 8, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvonen, K.L.; Baer, R.J.; Rogers, E.E.; Steurer, M.A.; Ryckman, K.K.; Feuer, S.K.; Anderson, J.G.; Franck, L.S.; Gano, D.; Petersen, M.A.; et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes through 1 year of life in infants born prematurely: A population based study in California. J. Perinatol. 2021, 41, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasch, J.L.; Klebanoff, M.; Frey, H.A.; Slaughter, J.; Backes, C.; Landon, M.B.; Costantine, M.M.; Lynch, C.D.J.; Venkatesh, K.K. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Periviable Birth in the United States, 2014-2018. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S234–S235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, P.; Maudsley, G.; Pennington, A.; Schlüter, D.K.; Barr, B.; Paranjothy, S.; Taylor-Robinson, D. Mediators of socioeconomic inequalities in preterm birth: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgen, C.S.; Bjørk, C.; Andersen, P.K.; Mortensen, L.H.; Andersen, A.N. Socioeconomic position and the risk of preterm birth—A study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 37, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, N.; Wachtel, E.V.; Bailey, S.M.; Espiritu, M.M. Implicit Physician Biases in Periviability Counseling. J. Pediatr. 2018, 197, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltman, D.M.; Fritz, K.A.; Datta, A.; Carlos, C.; Hayslett, D.; Tonismae, T.; Lawrence, C.; Batton, E.; Coleman, T.; Jain, M.; et al. Antenatal Periviability Counseling and Decision Making: A Retrospective Examination by the Investigating Neonatal Decisions for Extremely Early Deliveries Study Group. Am. J. Perinatol. 2020, 37, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Patients n = 138 |

|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 32.3 (28.1, 36.8) |

| Nulliparous | 80 (58.0) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 29.2 (24.4, 32.8) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 21 (15.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 57 (41.3) |

| Other/Unknown | 60 (43.5) |

| Government insurance | 62 (44.9) |

| Married | 63 (45.7) |

| English proficiency | 127 (92.0) |

| Year of delivery | |

| 2019 | 33 (23.9) |

| 2020 | 36 (26.1) |

| 2021 | 33 (23.9) |

| 2022 | 36 (26.1) |

| Gestational age on admission (weeks) | 23.8 (22.9, 24.9) |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 24.3 (23.2, 25.1) |

| Spontaneous preterm delivery | 114 (82.6) |

| Cephalic presenting fetus | 67 (48.9) [n = 137] |

| Female neonate | 63 (46.0) [n = 137] |

| Birth weight (grams) | 655.0 (530.0, 780.0) [n = 133] |

| Characteristic | Neonatology Consult | Expectant Management | Neonatal Full Intervention | Neonatal Comfort Care | Pregnancy Termination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White [n = 21] | 10 (47.6) | 18 (85.7) | 19 (90.5) | 9 (60.0) [n = 15] | 7 (33.3) |

| Non-Hispanic Black [n = 57] | 39 (68.4) | 52 (91.2) | 50 (87.7) | 17 (37.8) [n = 45] | 22 (38.6) |

| Other/Unknown [n = 60] | 48 (80.0) | 57 (95.0) | 53 (88.3) | 28 (56.0) [n = 50] | 33 (55.0) |

| p value * | 0.019 | 0.334 | 0.944 | 0.137 | 0.104 |

| Government insurance [n = 62] | 42 (67.7) | 60 (96.8) | 52 (83.9) | 27 (52.9) [n = 51] | 29 (46.8) |

| p value * | 0.554 | 0.111 | 0.133 | 0.453 | 0.694 |

| Married [n = 63] | 49 (77.8) | 61 (96.8) | 58 (92.1) | 27 (52.9) [n = 51] | 28 (44.4) |

| p value * | 0.078 | 0.057 | 0.219 | 0.453 | 0.917 |

| Nulliparous [n = 80] | 59 (73.8) | 73 (91.3) | 71 (88.8) | 33 (51.6) [n = 64] | 38 (47.5) |

| p value * | 0.296 | 0.761 | 0.882 | 0.541 | 0.476 |

| English proficiency [n = 127] | 89 (70.1) | 116 (91.3) | 112 (88.2) | 51 (50.5) [n = 101] | 57 (44.9) |

| p value * | 1.000 | 0.600 | 1.000 | 0.490 | 1.000 |

| Components of Periviability Counseling | Median SVI Among Those Whose Counseling Included Components | Median SVI Among Those Whose Counseling Excluded Components | p Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatology consult | 0.65 (0.44, 0.85) | 0.65 (0.53, 0.86) | 0.643 |

| Expectant management | 0.65 (0.44, 0.86) | 0.62 (0.53, 0.81) | 0.972 |

| Neonatal full intervention | 0.65 (0.44, 0.83) | 0.73 (0.545, 0.93) | 0.440 |

| Neonatal comfort care | 0.57 (0.26, 0.81) | 0.70 (0.52, 0.92) | 0.081 |

| Pregnancy termination | 0.62 (0.42, 0.81) | 0.67 (0.47, 0.87) | 0.336 |

| Components of Periviability Counseling | All n = 138 | Low Vulnerability (Q1) n = 13 | Moderately Low Vulnerability (Q2) n = 24 | Moderately High Vulnerability (Q3) n = 44 | High Vulnerability (Q4) n = 57 | p Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discussed fetal monitoring | 41 (33.6) [n = 122] | 3 (27.3) [n = 11] | 6 (26.1) [n = 23] | 15 (38.5) [n = 39] | 17 (34.7) [n = 49] | 0.749 |

| Discussed mode of delivery | 94 (77.0) [n = 122] | 6 (54.5) [n = 11] | 21 (91.3) [n = 23] | 27 (69.2) [n = 39] | 40 (81.6) [n = 49] | 0.052 |

| Discussed pregnancy termination via induction | 36 (58.1) (n = 62) | 5 (62.5) [n = 8] | 5 (50.0) [n = 10] | 11 (55.0) [n = 20] | 15 (62.5) [n = 24] | 0.915 |

| Discussed pregnancy termination via dilation and evacuation | 17 (27.4) (n = 62) | 4 (50.0) [n = 8] | 1 (10.0) [n = 10] | 4 (20.0) [n = 20] | 8 (33.3) [n = 24] | 0.230 |

| Betamethasone administered | 94 (77.0) [n = 122] | 5 (45.5) [n = 11] | 20 (87.0) [n = 23] | 28 (71.8) [n = 39] | 41 (83.7) [n = 49] | 0.025 |

| Magnesium administered | 97 (79.5) [n = 122] | 6 (54.5) [n = 11] | 20 (87.0) [n = 23] | 29 (74.4) [n = 39] | 42 (85.7) [n = 49] | 0.092 |

| Group B strep prophylaxis administered | 74 (60.7) [n = 122] | 6 (54.5) [n = 11] | 14 (60.9) [n = 23] | 20 (51.3) [n = 39] | 34 (69.4) [n = 49] | 0.366 |

| Delivered via cesarean section | 69 (50.4) | 5 (38.5) | 15 (62.5) | 21 (48.8) [n = 43] | 28 (49.1) | 0.527 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piltch, G.; Comfort, L.; Krantz, D.; Jackson, F.; Blitz, M.J.; Rochelson, B. Social Vulnerability and Pregnancy Option Counseling in the Setting of Periviable Delivery. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020466

Piltch G, Comfort L, Krantz D, Jackson F, Blitz MJ, Rochelson B. Social Vulnerability and Pregnancy Option Counseling in the Setting of Periviable Delivery. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(2):466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020466

Chicago/Turabian StylePiltch, Gillian, Lizelle Comfort, David Krantz, Frank Jackson, Matthew J. Blitz, and Burton Rochelson. 2025. "Social Vulnerability and Pregnancy Option Counseling in the Setting of Periviable Delivery" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 2: 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020466

APA StylePiltch, G., Comfort, L., Krantz, D., Jackson, F., Blitz, M. J., & Rochelson, B. (2025). Social Vulnerability and Pregnancy Option Counseling in the Setting of Periviable Delivery. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020466