Early Surgical Resection in Pediatric Patients with Localized Ileo-Cecal Crohn’s Disease: Results of a Retrospective Multicenter Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Endpoints

3.1.1. Primary Endpoint

3.1.2. Secondary Endpoint

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baumgart, D.C.; Sandborn, W.J. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2012, 380, 1590–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Allmen, D. Pediatric Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2018, 31, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Levine, A.; Koletzko, S.; Turner, D.; Escher, J.C.; Cucchiara, S.; de Ridder, L.; Kolho, K.L.; Veres, G.; Russell, R.K.; Paerregaard, A.; et al. European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. ESPGHAN revised porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 58, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groof, E.J.; Rossen, N.G.; van Rhijn, B.D.; Karregat, E.P.; Boonstra, K.; Hageman, I.; Bennebroek Evertsz, F.; Kingma, P.J.; Naber, A.H.; van den Brande, J.H.; et al. Burden of disease and increasing prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in a population-based cohort in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 28, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomollón, F.; Dignass, A.; Annese, V.; Tilg, H.; Van Assche, G.; Lindsay, J.O.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Cullen, G.J.; Daperno, M.; Kucharzik, T.; et al. ECCO 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J. Crohns. Colitis. 2017, 11, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.; Bonovas, S.; Doherty, G.; Kucharzik, T.; Gisbert, J.P.; Raine, T.; Adamina, M.; Armuzzi, A.; Bachmann, O.; Bager, P.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment. J. Crohns. Colitis. 2020, 14, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruemmele, F.M.; Veres, G.; Kolho, K.L.; Griffiths, A.; Levine, A.; Escher, J.C.; Amil Dias, J.; Barabino, A.; Braegger, C.P.; Bronsky, J.; et al. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation; European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Consensus guidelines of ECCO/ESPGHAN on the medical management of pediatric Crohn’s disease. J. Crohns. Colitis. 2014, 8, 1179–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hecke, J.; Wauters, L.; Veereman, G. Clinical outcomes in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients: A systematic review of prospective studies. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 38, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amil-Dias, J.; Kolacek, S.; Turner, D.; Pærregaard, A.; Rintala, R.; Afzal, N.A.; Karolewska-Bochenek, K.; Bronsky, J.; Chong, S.; Fell, J.; et al. Surgical Management of Crohn Disease in Children: Guidelines From the Paediatric IBD Porto Group of ESPGHAN. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Lightner, A.L.; Spinelli, A.; Kotze, P.G. Perioperative management of ileocecal Crohn’s disease in the current era. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 14, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemelman, W.A.; Warusavitarne, J.; Sampietro, G.M.; Serclova, Z.; Zmora, O.; Luglio, G.; van Overstraeten, A.d.B.; Burke, J.P.; Buskens, C.J.; Colombo, F.; et al. ECCO-ESCP Consensus on Surgery for Crohn’s Disease. J. Crohns. Colitis. 2018, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, G.R.; Loftus, E.V.; Isaacs, K.L.; Regueiro, M.D.; Gerson, L.B.; Sands, B.E. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn’s Disease in Adults. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 481–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.; Carmona, C.; George, B.; Epstein, J. Guideline Committee. Management of Crohn’s disease: Summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2019, 367, l5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamina, M.; Bonovas, S.; Raine, T.; Spinelli, A.; Warusavitarne, J.; Armuzzi, A.; Bachmann, O.; Bager, P.; Biancone, L.; Bokemeyer, B.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Surgical Treatment. J. Crohns. Colitis. 2020, 14, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smida, M.; Miloudi, N.; Hefaiedh, R.; Zaibi, R. Emergency surgery for Crohn’s disease. Tunis Med. 2016, 94, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ponsioen, C.Y.; de Groof, E.J.; Eshuis, E.J.; Gardenbroek, T.J.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; Hart, A.; Warusavitarne, J.; Buskens, C.J.; van Bodegraven, A.A.; Brink, M.A.; et al. Laparoscopic ileocaecal resection versus infliximab for terminal ileitis in Crohn’s disease: A randomised controlled, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 785–792, Erratum in Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubin, G.; Peter, L. Predicting Endoscopic Crohn’s Disease Activity Before and After Induction Therapy in Children: A Comprehensive Assessment of PCDAI, CRP, and Fecal Calprotectin. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 1386–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Daperno, M.; D’Haens, G.; Van Assche, G.; Baert, F.; Bulois, P.; Maunoury, V.; Sostegni, R.; Rocca, R.; Pera, A.; Gevers, A.; et al. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn’s disease: The SES-CD. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2004, 60, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyams, J.; Markowitz, J.; Otley, A.; Rosh, J.; Mack, D.; Bousvaros, A.; Kugathasan, S.; Pfefferkorn, M.; Tolia, V.; Evans, J.; et al. Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborative Research Group. Evaluation of the pediatric crohn disease activity index: A prospective multicenter experience. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2005, 41, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.S. Clinical Aspects and Treatments for Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2019, 22, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ng, S.C.; Shi, H.Y.; Hamidi, N.; Underwood, F.E.; Tang, W.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017, 390, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, S.R.; Graff, L.A.; Wilding, H.; Hewitt, C.; Keefer, L.; Mikocka-Walus, A. Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses-Part I. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, N.; Dusheiko, M.; Maillard, M.H.; Rogler, G.; Brüngger, B.; Bähler, C.; Pittet, V.E.H.; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. The Evolution of Health Care Utilisation and Costs for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Over Ten Years. J. Crohns. Colitis. 2019, 13, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papamichael, K.; Gils, A.; Rutgeerts, P.; Levesque, B.G.; Vermeire, S.; Sandborn, W.J.; Vande Casteele, N. Role for therapeutic drug monitoring during induction therapy with TNF antagonists in IBD: Evolution in the definition and management of primary nonresponse. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Click, B.; Regueiro, M. Managing Risks with Biologics. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2019, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, M.; Liberato, N.L. Biological therapies in Crohn’s disease: Are they cost-effective? A critical appraisal of model-based analyses. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2014, 14, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelm, M.; Germer, C.T.; Schlegel, N.; Flemming, S. The Revival of Surgery in Crohn’s Disease-Early Intestinal Resection as a Reasonable Alternative in Localized Ileitis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Groof, E.J.; Stevens, T.W.; Eshuis, E.J.; Gardenbroek, T.J.; Bosmans, J.E.; van Dongen, J.M.; Mol, B.; Buskens, C.J.; Stokkers, P.C.F.; Hart, A.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic ileocaecal resection versus infliximab treatment of terminal ileitis in Crohn’s disease: The LIR!C Trial. Gut 2019, 68, 1774–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, T.W.; Haasnoot, M.L.; D’Haens, G.R.; Buskens, C.J.; de Groof, E.J.; Eshuis, E.J.; Gardenbroek, T.J.; Mol, B.; Stokkers, P.C.F.; Bemelman, W.A.; et al. Laparoscopic ileocaecal resection versus infliximab for terminal ileitis in Crohn’s disease: Retrospective long-term follow-up of the LIR!C trial. Lancet. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, M.; Ebert, A.C.; Poulsen, G.; Ungaro, R.C.; Faye, A.S.; Jess, T.; Colombel, J.F.; Allin, K.H. Early Ileocecal Resection for Crohn’s Disease Is Associated With Improved Long-term Outcomes Compared With Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 976–985.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maruyama, B.Y.; Ma, C.; Panaccione, R.; Kotze, P.G. Early Laparoscopic Ileal Resection for Localized Ileocecal Crohn’s Disease: Hard Sell or a Revolutionary New Norm? Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2021, 7, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beelen, E.M.J.; Arkenbosch, J.H.C.; Erler, N.S.; Sleutjes, J.A.M.; Hoentjen, F.; Bodelier, A.G.L.; Dijkstra, G.; Romberg-Camps, M.; de Boer, N.K.; Stassen, L.P.S.; et al. Impact of timing of primary ileocecal resection on prognosis in patients with Crohn’s disease. BJS Open 2023, 7, zrad097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kelm, M.; Anger, F.; Eichlinger, R.; Brand, M.; Kim, M.; Reibetanz, J.; Krajinovic, K.; Germer, C.T.; Schlegel, N.; Flemming, S. Early Ileocecal Resection Is an Effective Therapy in Isolated Crohn’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- SURGICAL IBD LATAM CONSORTIUM. Earlier surgery is associated to reduced postoperative morbidity in ileocaecal Crohn’s disease: Results from SURGICROHN—LATAM study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avellaneda, N.; Haug, T.; Ørntoft, M.B.W.; Harsløf, S.; Skovgaard Larsen, L.P.; Tøttrup, A. Short-Term Results of Operative Treatment of Primary Ileocecal Crohn’s Disease: Retrospective, Comparative Analysis between Early (Luminal) and Complicated Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dreznik, Y.; Samuk, I.; Shouval, D.S.; Paran, M.; Matar, M.; Shamir, R.; Totah, M.; Kravarusic, D. Recurrence rates following ileo-colic resection in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2023, 39, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotze, P.G.; Magro, D.O.; Martinez, C.A.R.; Spinelli, A.; Yamamoto, T.; Warusavitarne, J.; Coy, C.S.R. Long Time from Diagnosis to Surgery May Increase Postoperative Complication Rates in Elective CD Intestinal Resections: An Observational Study. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 4703281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Variable | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size of ulcers | None | Aphthous ulcers (Ø 0.1 to 0.5 cm) | Large ulcers (Ø 0.5 to 2 cm) | Very large ulcers (Ø > 2 cm) |

| Ulcerated surface | None | <10% | 10–30% | >30% |

| Affected surface | Unaffected segment | <50% | 50–75% | >75% |

| Presence of narrowings | None | Single, can be passed | Multiple, can be passed | Cannot be passed |

| Category | Parameter | Detailed Description | Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| History (recall, 1 wk) | Abdominal pain | None | 0 |

| Mild (brief, does not interfere with activities) | 5 | ||

| Mod/severe (daily, longer lasting, affects activities, nocturnal) | 10 | ||

| Stools (per day) | 0–1 liquid stools, no blood | 0 | |

| Up to 2 semi-formed with small blood, or 2–5 liquid | 5 | ||

| Gross bleeding, or ≥6 liquid, or nocturnal diarrhea | 10 | ||

| Patient functioning, general wellbeing (recall, 1 wk) | No limitation of activities | 0 | |

| Occasional difficulty in maintaining age-appropriate activities | 5 | ||

| Frequent limitation of activity, very poor | 10 | ||

| Laboratory | Hematocrit (%) (use age-specific reference) | Normal | 0 |

| Mild decrease | 2.5 | ||

| Mod/severe decrease | 5 | ||

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | <20 | 0 | |

| 20–50 | 2.5 | ||

| >50 | 5 | ||

| Albumin (g/dL) | ≥3.5 | 0 | |

| 3.1–3.4 | 5 | ||

| ≤3.0 | 10 | ||

| Examination | Weight | Weight gain or voluntary weight stable/loss | 0 |

| Involuntary weight stable, weight loss 1–9% | 5 | ||

| Weight loss ≥ 10% | 10 | ||

| Height at diagnosis | <1 channel decrease | 0 | |

| ≥1, <2 channel decrease | 5 | ||

| ≥2 channel decrease | 10 | ||

| Height follow-up | Height velocity ≥ −1 SD | 0 | |

| Height velocity < −1 SD, >−2 SD | 5 | ||

| Height velocity ≤ −2 SD | 10 | ||

| Abdomen | No tenderness, no mass | 0 | |

| Tenderness, or mass without tenderness | 5 | ||

| Tenderness, involuntary guarding, definite mass | 10 | ||

| Perirectal disease | None, asymptomatic tags | 0 | |

| 1–2 Indolent fistula, scant drainage, no tenderness | 5 | ||

| Active fistula, drainage, tenderness, or abscess | 10 | ||

| Extraintestinal manifestations (n) | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 5 | ||

| ≥2 | 10 |

| Parameter | Category | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | Male | 19 (65.5) |

| Female | 10 (34.5) | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | Median (range) | 12 (5–16) |

| Age at surgery, years | Median (range) | 14 (8–20) |

| Site of disease, n (%) | Ileal | 5 (17.2) |

| Ileocecal | 17 (58.6) | |

| Ileocolic | 7 (24.1) | |

| Indication for surgery, n (%) | Stenosis | 18 (62.1) |

| Fistula | 0 | |

| Stenosis and fistula | 6 (20.7) | |

| Unresponsive to medical treatment | 5 (17.3) | |

| Medical treatment, months | Median (range) | 10 (1–144) |

| SES-CD 1 | Median (range) | 12 (1–15) |

| Mild, n (%) | 2 (6.9) | |

| Moderate, n (%) | 15 (51.7) | |

| Severe, n (%) | 12 (41.4) | |

| PCDAI 2 | Median (range) | 30 (10–50) |

| Mild, n (%) | 9 (31.0) | |

| Moderate, n (%) | 7 (24.1) | |

| Severe, n (%) | 13 (44.8) |

| Parameter | Category | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical technique (n,%) | Right emicolectomy | 18 (62.1) |

| Ileocolic resection | 11 (37.9) | |

| Surgical approach (n,%) | Open | 6 (20.6) |

| Videolaparoscopy | 19 (65.5) | |

| Conversion | 4 (13.7) | |

| Complication rate (n,%) | 2 (6.9) |

| Parameter | Category | Before Surgery | After Surgery | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

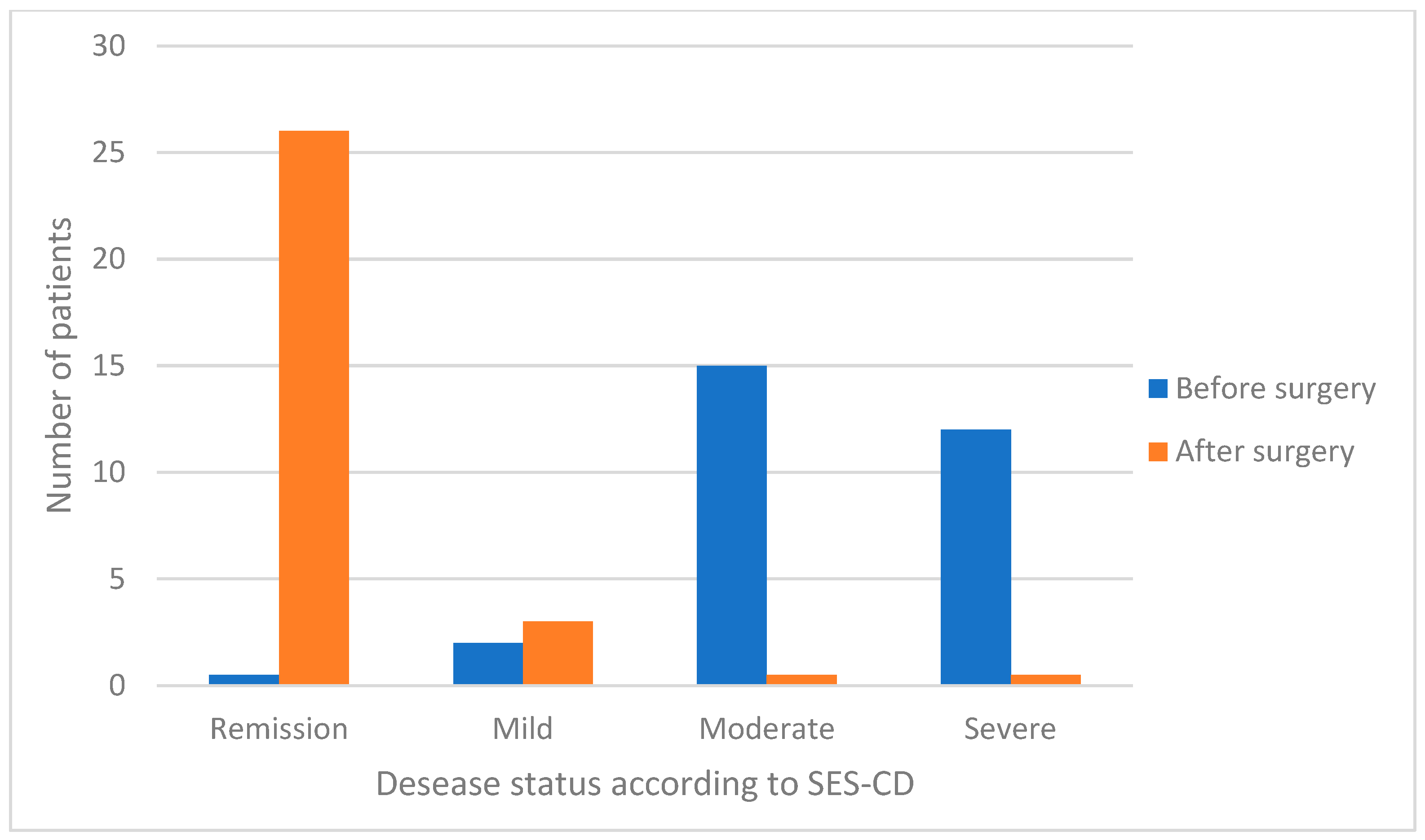

| SES-CD 1 | Median (range) | 12 (1–15) | 0 (0–6) | <0.0001 |

| Remission (<3), (n, %) | 0 | 26 (89.7) | 0.0001 | |

| Mild (3–6), (n %) | 2 (6.9) | 3 (10.3) | 0.639 | |

| Moderate (7–14), (n. %) | 15 (51.7) | 0 | 0.0001 | |

| Severe (≥15), (n. %) | 12 (41.4) | 0 | 0.0001 | |

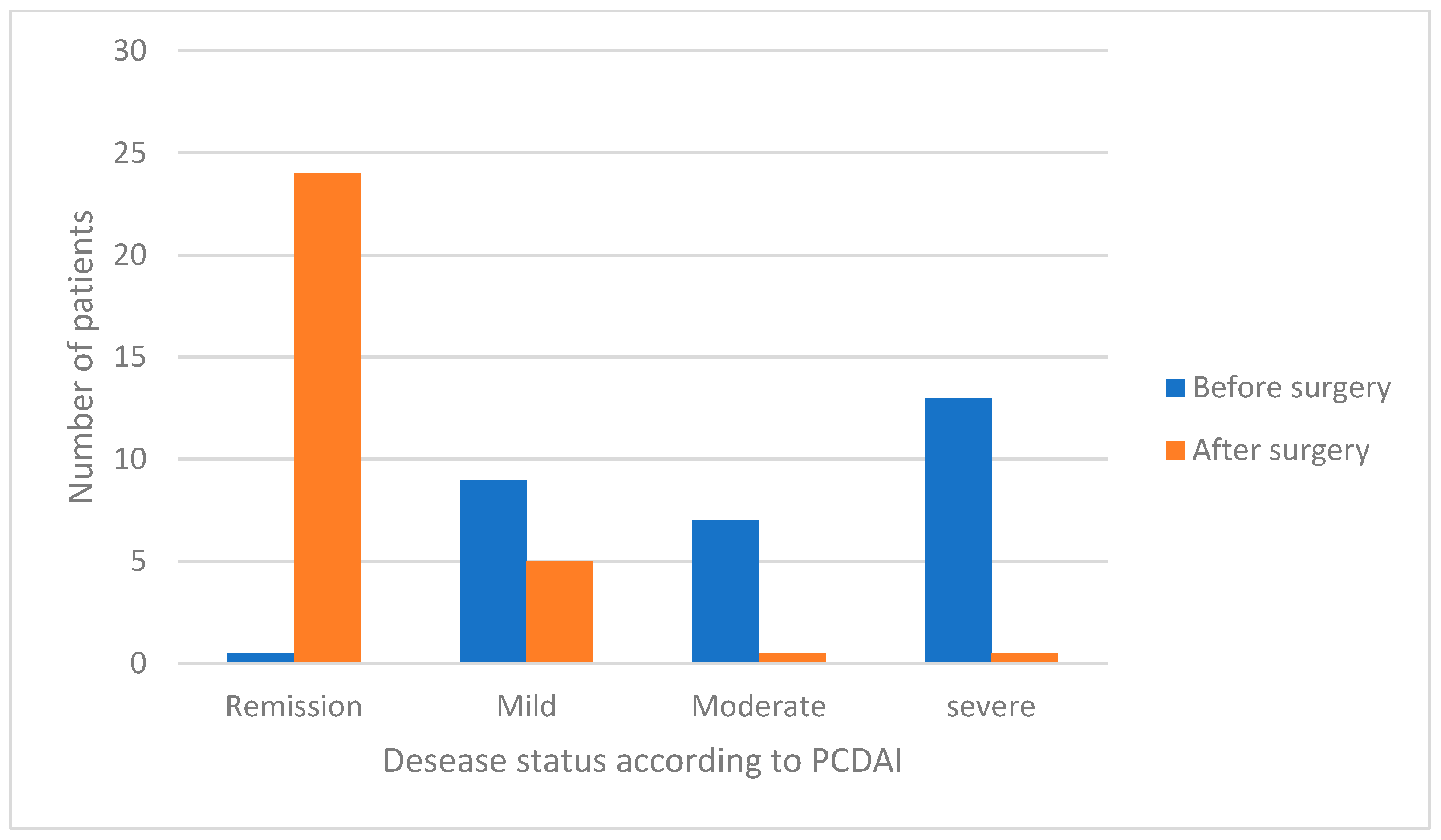

| p-CDAI 2 | Median (range) | 30 (10–50) | 0 (0–15) | <0.0001 |

| Remission (<10), (n. %) | 0 | 24 (82.8) | 0.0001 | |

| Mild (10–27), (n. %) | 9 (31.0) | 5 (17.2) | 0.219 | |

| Moderate (28–37), (n. %) | 7 (24.1) | 0 | 0.0048 | |

| Severe (≥38), (n. %) | 13 (44.8) | 0 | 0.0001 | |

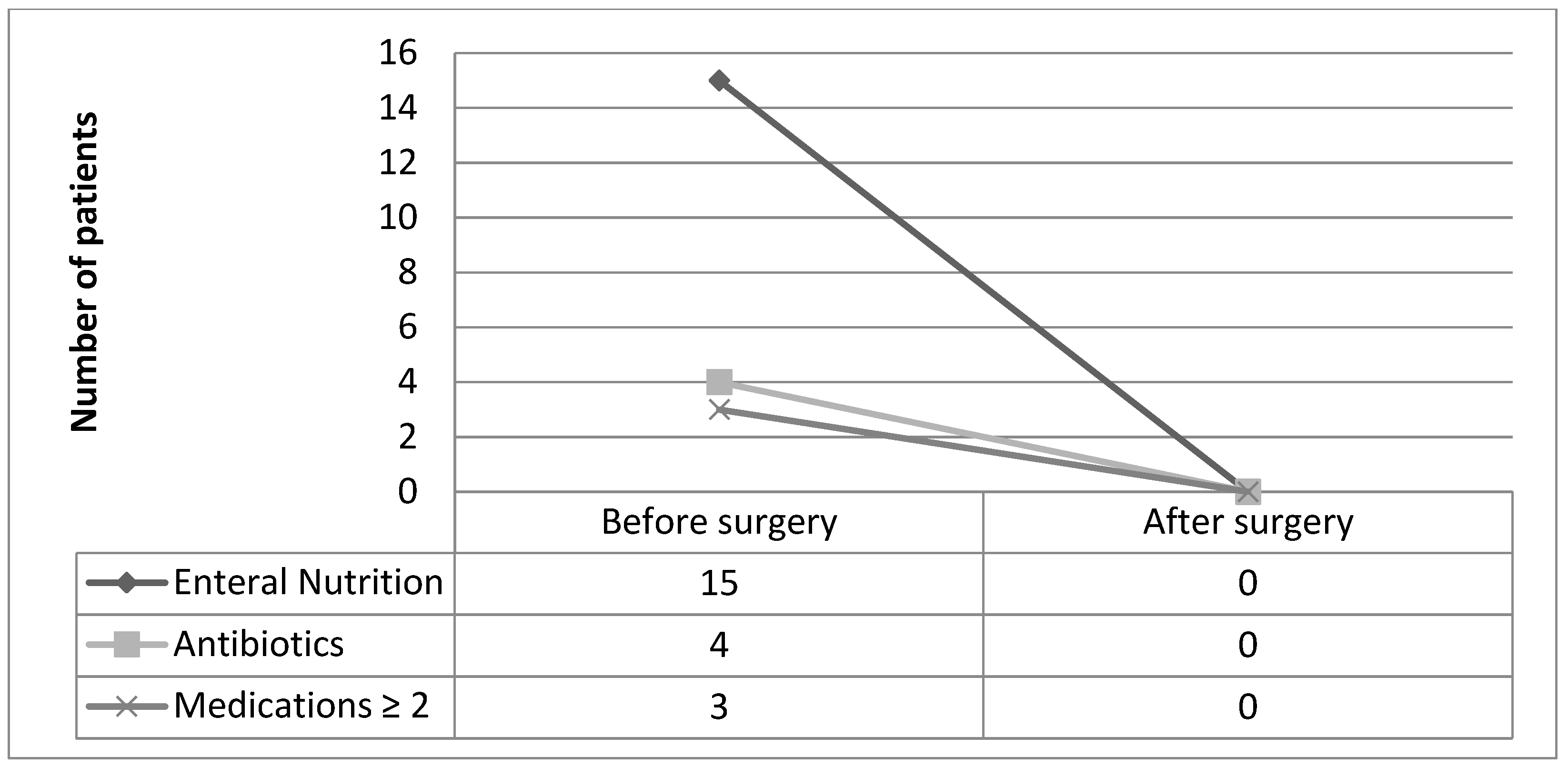

| Medical Therapy | Enteral nutrition (n. %) | 15 (51.7) | 0 | 0.0001 |

| Antiobiotics (n. %) | 4 (13.8) | 0 | 0.0382 | |

| Antinflammatory (n. %) | 2 (6.9) | 6 (20.7) | 0.128 | |

| Azathioprine (n. %) | 6 (20.7) | 6 (20.7) | 1.0 | |

| Biological therapies (n. %) | 19 (65.5) | 17 (58.6) | 0.588 | |

| Medications ≥2 (n. %) | 3 (10.3) | 0 | 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madaffari, I.; Muttillo, E.M.; La Franca, A.; Massimi, F.; Castagnola, G.; Coppola, A.; Furio, S.; Piccirillo, M.; Ferretti, A.; Mennini, M.; et al. Early Surgical Resection in Pediatric Patients with Localized Ileo-Cecal Crohn’s Disease: Results of a Retrospective Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020404

Madaffari I, Muttillo EM, La Franca A, Massimi F, Castagnola G, Coppola A, Furio S, Piccirillo M, Ferretti A, Mennini M, et al. Early Surgical Resection in Pediatric Patients with Localized Ileo-Cecal Crohn’s Disease: Results of a Retrospective Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(2):404. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020404

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadaffari, Isabella, Edoardo Maria Muttillo, Alice La Franca, Fanny Massimi, Giorgio Castagnola, Alessandro Coppola, Silvia Furio, Marisa Piccirillo, Alessandro Ferretti, Maurizio Mennini, and et al. 2025. "Early Surgical Resection in Pediatric Patients with Localized Ileo-Cecal Crohn’s Disease: Results of a Retrospective Multicenter Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 2: 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020404

APA StyleMadaffari, I., Muttillo, E. M., La Franca, A., Massimi, F., Castagnola, G., Coppola, A., Furio, S., Piccirillo, M., Ferretti, A., Mennini, M., Parisi, P., Cozzi, D. A., Ceccanti, S., Felici, E., Alessio, P. P., Lisi, G., Illiceto, M. T., Sperduti, I., Di Nardo, G., & Mercantini, P. (2025). Early Surgical Resection in Pediatric Patients with Localized Ileo-Cecal Crohn’s Disease: Results of a Retrospective Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(2), 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14020404